Abstract

Although chickens are not susceptible to SARS-CoV-2, several coronavirus disease outbreaks have been described concerning poultry processing facilities in different countries. The COVID-19 pandemic and the developed strain caused 2nd, 3rd, and recent Indian strain waves of epidemics that have led to unexpected consequences, such as forced reductions in demands for some industries, transportation systems, employment, and businesses due to public confinement. Besides, poultry processing plants' conditions exacerbate the risks due to the proximity on the line, cold, and humidity. Most workers do not have access to paid sick time or adequate health care, and because of the low wages, they have limited reserves to enable them to leave steady employment. In addition, workers in meat and poultry slaughterhouses may be infected through respiratory droplets in the air and/or from touching dirty surfaces or objects such as workstations, break room tables, or tools. Egg prices have increased dramatically during the lockdown as consumers have started to change their behaviors and habits. The COVID pandemic might also substantially impact the international poultry trade over the next several months. This review will focus on the effect of COVID-19 on poultry production, environmental sustainability, and earth systems from different process points of view.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Coronavirus infections have been associated with many diseases, such as the Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) (WHO 2019) and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) (Law et al. 2020) in humans. Recently, a new coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2 or COVID-19) has been isolated; it is responsible for the recent COVID-19 pandemic, and new strains developed that spread in European Union (EU), causing the 2nd lockdown (Alagawany et al. 2021; Saghir et al. 2021). COVID-19 infection causes a systemic disease that is spread via airborne/droplets/aerosol. COVID-19 has indirectly affected humans, animal production, the environment, earth systems, social and economic conditions worldwide (Sharun et al. 2021). There have been rumors about the potential involvement of eggs and chicken meat in the spread f COVID-19, which resulted in a dramatic drop in demand for poultry goods beginning in February 2020, just before the declaration of the lockout and culminating in the deterioration of poultry economics due to working capital erosion. From local farmers to large integrators, all aspects of poultry processing were severely impacted, much worse than the Avian influenza outbreak of 2006 (Das and Samanta 2021).

There is great attention on the adverse impact of the environment inside poultry house and increase the harmful dust and gaseous and the incidences of asthma, allergy diseases and repository and pulmonary disorders diseased among poultry workers and keepers. In addition, a high prevalence of nasal (51.1%) and asthmatic (42.5%) symptoms were observed in poultry keepers mainly, which may increase the susceptibility of works to Covid-19 (Viegas et al. 2013; Arcangeli et al. 2020; Clarke et al. 2021). Recent evidence indicates high incidences of COVID-19 among patients with chronic diseases and respiratory diseases (Hafez and Attia 2020). The contents of nitrogen (N) and phosphorus (P) in poultry litter and its negative impact on soil surface and groundwater because of continuous poultry litter application raises the risk of depletion of surface and the quality of the groundwater supplies (Bolan et al. 2010). The use of poultry litter has been shown to raise the edge-of-field losses of N and P in surface and subsurface runoff. Nitrate-N losses in groundwater will accumulate to amounts that surpass reasonable human intake limits (10 mg/L) (Colt 2006). Therefore, it is logical to expect the direct and indirect relationship between the economic and environmental influence of COVID-19 with concern to the poultry production sector through a health issue. This review shed light on the impact of COVID-19 on poultry production and the environment.

COVID-19

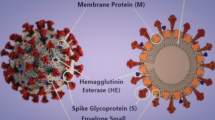

The family Coronaviridae contains two subfamilies: Torovirinae and Coronavirinae. Coronavirinae comprises four genera: Alphacoronavirus and Betacoronavirus mainly infect mammals, Gammacoronavirus infects avian species, and Deltacoronavirus infects mammalian and avian species (Phan et al. 2018; Attia et al. 2021). Torovirinae is divided into two genera: Torovirus, which originates from mammals, and Bafinivirus, isolated from fish (Tokarz et al. 2015) (Fig. 1). The different serotypes and varieties of COVID-19 are summarized in Table 1.

The Betacoronavirus genus contains COVID-19, SARS-CoV, and MERS-CoV (Shereen et al. 2020). COVID-19 is an enveloped virus that is highly infectious, even though it is easily destroyed by soap and common disinfectants. COVID-19 infection causes a systemic disease in which fever, dry cough, and fatigue have been most commonly reported; in some cases, diarrhea and vomiting can also be observed. Although chickens are not susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 (Schlottau et al. 2020), several coronavirus disease outbreaks have been described concerning poultry processing facilities in different countries as Brazil, Canada, and Spain (Durand-Moreau et al. 2020). Studies have linked livestock plants to a high potential for a community spread in the surrounding areas (Middleton et al. 2020; Taylor et al. 2020). Work routines in livestock processing make plants susceptible to local outbreaks of respiratory viruses. The long work shifts near coworkers, difficulty maintaining proper face-covering due to physical demands, and shared transportation among workers (Taylor et al. 2020). Besides, the virus thrives in lower temperatures and very high or very low relative humidity, and metallic surfaces retain live viruses for longer than other environments (Middleton et al. 2020).

The virus is thought to spread principally via respiratory droplets from an infected person to a healthy one through close contact. Strategies to prevent the spread and the strengthening of COVID-19 include increasing public awareness about transmission and decreasing trade activities. The possibility of the viruses spread among people is related to the biological properties of each virus. Still, it is also affected by external factors such as temperature, humidity, population density, and thus lack of hospital beds (Islam et al. 2020). In addition, the symptoms of the infection have multiple facets.

The public services and facilities must provide decontaminating reagents for cleaning hands daily. In addition, physical contact with wet and contaminated objects should be considered in dealing with the virus, avoiding contact with confirmed or suspected patients, and using face protective devices (Rothan and Byrareddy 2020; Islam et al. 2020).

Another way to contrast the SARS-CoV-2 spread is to know the virus's mechanisms and develop appropriate therapeutic strategies. Essential acquired knowledge is that the virus comes in the human cells through its high binding affinity with angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) (Benseñor and Lotufo 2020; Chen et al. 2020). So, Chen et al. (2020) proposed that specific antibodies and small molecules can prevent the binding between ACE2 and the receptors (RBD) of the virus, and this way could represent a potential strategy against COVID-19 disease prevention and control.

To control a further outbreak, strategies should be developed and applied around the world. A myriad of lessons has been learned from the COVID-19 pandemic, which pays great attention to the relationship among humans, wild animals, and livestock. Where there is a high human population density, the government in each country must be ready with specific pandemic plans to avoid the suffering of the health systems (Benseñor and Lotufo 2020). Other lessons will be learned because it will take time to develop an effective and successful vaccine and/or specific antiviral therapy for COVID-19 (Islam et al. 2020; Rahman et al. 2020). Therefore, it is essential to determine whether a neutralizing antibody and/or SARS-CoV-2-specific T cell response is sufficient to prevent clinical disease transmission, determine the magnitude of the reactions required to provide protection and the longevity of these protective responses (Sariol and Perlman 2020).

In 2019, the weakness of health systems worldwide came into focus due to insufficient hospital beds, lack of adequate diagnostic kits, inadequately trained physicians, and high numbers of deaths, including health professionals, physicians, nurses, and health care workers. Therefore, it is fundamental to pay more attention to the development of medical education, health care programs, fighting poverty, and addressing hunger rather than developing instruments of war, namely bombs, missiles, and nuclear weapons. Furthermore, with limited knowledge about the COVID-19 pandemic and our increasingly interlinked and multifaceted world, what is ultimately and necessarily required are robustness, flexibility, and pliability to deal with unforeseen future situations and dialogs (Luo 2020).

In general, the average worldwide lethality of SARS-COV-2 is approximately 2.21% (total deaths divided by the total confirmed cases), which is quite a bit lower than SARS (9.6%), and far below MERS-CoV (34%) and Ebola (65.7%). The overall numbers of infections worldwide, specifically in several leading coronavirus countries and authors' countries (Brazil, Germany, Italy, Saudi Arabia; Egypt) are reported in Table 2. The cases are continuing to growth with the release of the 2nd and 3rd waves of the disease and the new Indian strains. USA, India, Brazil, Russia, and France are the leading countries in the incidences and death in Covid-19 cases. The USA is the dominant country in confirmed cases and death, followed by India and Brazil, which showed a high incidence of confirmed cases. From the death cases per million-population point of view, the countries can be ranked as Italy>USA>Brazil> France>Russia>Germany>Saudi Arabia> India> Egypt. In Saudi Arabia, prevention and control programs for COVID-19 have so far achieved considerable success. As of February 28, 2021, the confirmed number of cases infected with COVID-19, as reported by (19 and 20) in Saudi Arabia, was 362,601 (1.04% of the total population), and recovered patients was 356,387, which represents 98.3 of the confirmed cases. Thus, there have been 6,214 deaths or 179 cases per million of the population (WHO 2020a). In Egypt, India, and Saudi Arabia, the cases are much lower than the global cases, showing 104, 108, and 179 cases per million people, respectively, compared to the average global cases with 230 per million people. Details about total cases and deaths due to COVID-19 around the globe are shown in Table 3.

These discrepancies may be due to several factors, such as early lockdown, decreased trade activities that block transmission pathways, and increasing public awareness of disease control and prevention, which was initiated with early confirmed cases in March 2020. In addition to the use of active and random surveys, other programs, such as working from home, may be implemented as a part of the control and prevention programs when necessary.

In Italy, the situation has been quite different, with 2,067,487 confirmed cases and 73,029 death cases. Several hypotheses have been considered to explain the high mortality rate, as a relatively older average age of the Italian people, more intensive social contacts among children and older people, and underestimating the total number of COVID-19 cases in Italy (Worldmeters 2020). According to Onder et al. (2020) and WHO (2020a), from December 31, 2019 to February 28, 2021 there have been 25,933,806 confirmed COVID-19 cases in Europe. The five countries reporting the most cases are Russia (3,131,550), the United Kingdom (UK) (2,382,869), Italy (2,067,487), Spain (1,893,502), and Germany (1,687,185). In Germany, the number of deaths was 384 per million, showing the lowest number as of February 28, 2020 (WHO 2020a; Worldmeters 2020).

COVID-19 was first detected in Brazil on February 25, 2020, making it the first Latin American country to report a case of the novel coronavirus (WHO 2020a). Since then, the number of infections has risen drastically; today, Brazil is the Latin American country with the highest number of confirmed COVID-19 cases (COVID-19 situation update worldwide 2020; Montanez 2020a), with over 7,561,550 (Onder et al. 2020). The first death due to this disease was registered on March 17, 2020 (COVID-19 situation update worldwide 2020), and approximately 3 months later, the number of fatalities surpassed 50,617, with 594,108 recoveries (Montanez 2020b; Scalzaretto 2020). As of December 31, 2020, the number of deaths reached 192,681 cases (Onder et al. 2020, showing cumulative increase over time. The number of cases and deaths has probably been underestimated.

An experiment by the Imperial College (London, UK) about the spread rate of COVID-19 in 48 countries showed Brazil at the top. Large cities such as São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro are currently the top hotspots. Still, there are signs that infections are spreading into minor cities with insufficient numbers of ventilators and intensive care beds (Montanez 2020b; Scalzaretto 2020). While the World Health Organization (WHO) has suspended chloroquine trials in Brazil, the Health Ministry has issued a reference for the public health system to use the medicine in COVID-19 patients from the very early phases of the disease onward. This directive is contrary to recommendations from medical associations (Ficetola and Rubolini 2020; Montanez 2020b; Scalzaretto 2020).

The influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on the environment

The environmental effects of the COVID-19 pandemic have received relatively little attention. Still, this growing interest after the outbreak of 2nd and 3rd waves of COVID-19 and recently outbreak in India (WHO 2020b): The positive and negative impact of COVID-19 on the total environment, ecological sustainability, and earth systems have not yet be discussed. This pandemic has led to unexpected consequences, such as forced reductions in demands for industries, transportation systems, and all businesses due to public confinement; these declines have caused carbon emissions to drop. For example, in New York, air pollution has fallen by almost 50%. In China, emissions have shown a 25% decrease, and in Europe, nitrogen dioxide emissions dropped over Italy, Spain, and the UK (Ficetola and Rubolini 2020). Other positive influences include clear skies, wild animals roaming streets, clear water in the canals of Venice, Italy, and decreasing pollution elsewhere, particularly industrial areas (Capovilla 2020; Corrigan 2020; Ruiz 2020).

One of the other effects of the COVID-19 pandemic has been a drop in coal and oil consumption worldwide, a phenomenon that has contributed to a large-scale decline in air pollution (IEA 2020; Saadat et al. 2020). While this reduction is essential for environmental health in general, it also benefits individuals who contract COVID-19. Indeed, areas with higher air pollution have presented markedly higher mortality rates from COVID-19 (BBC News 2020).

The repeal of single-use plastic bans, a phenomenon that has translated into a heightened demand for bottled water, personal protective equipment (e.g., masks for individuals who must venture into public), plastic bags, and packaging (Tenenbaum 2020). Medical waste and the trash from personal protective equipment, such as gloves and masks, are also on the rise (Zambrano-Monserrate et al. 2020). Some fast food and retail chains have banned the use of reusable cups and food containers (Peszkô 2020). Thus, the oil industries have produced more plastics to mitigate financial losses (Van der Made 2020). The generation of inorganic and organic waste has been increased due to the consumer's demand for online shopping and home delivery, and trash recycling has been reduced in many countries because of the concerns about the hazard of SARS-COV-2 spreading in recycling centers (Zambrano-Monserrate et al. 2020).

It is possible that a virus can persist in drinking water, but COVID-19 has not been observed in drinking water supplies; based on present data, the hazard to water supplies is low. However, according to the WHO (2020b), studies of surrogate coronaviruses have indicated that the virus could remain infectious in water contaminated with feces for days to weeks. The influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on the environment is illustrated in Fig. 2.

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the poultry economy

Poultry producers have been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, but the influences vary substantially from one area to another. Indeed, each country differs concerning how the disease progresses. In a study performed in England and Spain (Clements 2020a), producers indicated a recent increase in product demands, with 17.4% mentioning that the rise had been marked. Nevertheless, this situation has not been universal because 37% stated that requests had dropped, with 28% indicating that the reduction had been considerable. In addition, there has been increased acceptance to perform work over the Internet in favor of live production; 17% of respondents stated that farms had used fewer laborers. Over 14% of respondents revealed that the pandemic had rejuvenated a switch to fully automatic slaughtering plants. According to 8% of respondents, the issues caused by the COVID-19 pandemic have encouraged them to hasten their plans for automatization (Clements 2020b).

In poultry, significant efforts have been made to restrict the avian infectious bronchitis virus (IBV) with is part of the genus Gammacoronavirus; it is not transmitted to humans. In addition, SARS-CoV and COVID-19 are from the same group and use the same ACE2 host cell receptor, and thus SARS-CoV does not infect or cause disease in poultry. This finding suggests that poultry are unlikely to serve as a reservoir for SARS coronaviruses (Hafez 2010).

The immune system of human and avian species varies greatly and thus vaccination protocols, the appropriate vaccine virus serotype, and applications are different (Hafez 2005; Torremorell and Bender 2020). The production of human vaccines is essential to safety and wellbeing. Poultry production has not been at risk to the global spread of SARS-CoV (Hafez 2010). Recent data have indicated that it is not associated with poultry or poultry products, and chickens are not susceptible to intranasal infection by the virus (Friedrich-Loefler-Institut 2020a, 2020b; Schlottau et al. 2020). All swabs and organ samples, and contact birds remained negative for COVID-19 RNA, while infected fruit bats and ferrets were susceptible to the infection; the symptoms were stronger in ferrets than fruit bats (Friedrich-Loefler-Institut 2020a). Additionally, Shi et al. (2020) stated that cats and ferrets are highly susceptible to COVID-19, dogs have a low risk, and livestock, including chickens, pigs, and ducks, are not vulnerable to the virus. Improved poultry resistance to COVID-19 based on enhanced hygiene, biosecurity, and immunity would provide additional benefits for producers (Hafez 2010). It is recognized that vitamins C, B6, and E and minerals such as zinc and magnesium have played and will continue to play vital roles in sustaining immune function during the COVID-19 pandemic (CSIS 2020).

The economic pressures induced by the COVID-19 pandemic can be seen from different points of view. For example, the pandemic has increased unemployment. Restaurants chains and retailers are trying to fulfill their obligations to their employees while attempting to keep their businesses solvent (Rahman et al. 2020). In addition, the conditions in poultry processing plants exacerbate the risks due to the proximity on the line, cold and humidity. Most of the workers do not have access to paid sick time or adequate health care, and because of the low wages, they have limited reserves to enable them to leave steady employment (CNN 2020).

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a huge impact on farmers and food suppliers in several ways. First, there are not enough people in slaughterhouses to process the poultry, and farmers are being forced to euthanize their stock. Recently, about 2 million chickens in Delaware and Maryland were humanely killed because processing plants are short-staffed (CNN 2020). Nonetheless, poultry is not affected by COVID-19 (Berkhout 2020) and do not transfer it to humans, and the animal feed industry has been influenced by the cessation of slaughterhouses (Brown and Fu 2020), restaurants, and fast-food chains around the world to avoid contamination among workers and consumers. The closure of processing facilities may ultimately cause the depopulation of millions of animals (chickens, pigs, and cattle) (McDougal 2020). Third, biosecurity is the main line of defense that each breeder, hatchery, and poultry owner has against diseases. Improvements in biosecurity practices will help workers remain safe. Personal and facility cleanliness and avoiding transporting contaminated material such as chicken manure are essential (Benjamin 2020; Montanez 2020a).

Meat and eggs

Workers in meat and poultry slaughterhouses have had to keep working during the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, their work situations in the slaughterhouses and zones, where they must remain near coworkers and directors, may considerably increase their possible exposure risk to COVID-19. In addition, workers in meat and poultry slaughterhouses may be infected through respiratory droplets in the air and/or from touching dirty surfaces or objects such as workstations, break room tables, or tools (CDC 2019).

Despite the COVID-19 pandemic, global food prices have remained stable. According to the Center for Strategic International Studies (CSIS 2020; Galimberti 2020), global prices only dropped 4.3% from February to March 2020 due to the demand for contractions amid lockdowns and quarantines (Welshans 2020). The need for poultry meat and eggs has increased at the retail level due to confinement. The retail market for poultry meat was amplified by nearly 75% during the panic buying phase, which took place in the first few weeks of the crisis; however, this demand has returned to normal levels. Demand for eggs has increased by 20–35% in England (NFU 2020).

The European Poultry Producers Association (AVEC) has observed a 10–30% reduction in broiler slaughtering in European Union (EU) member states (AVEC 2020). Furthermore, poultry prices have declined around 20% since the beginning of March 2020, reversing the trend in EU poultry meat prices from December 2019 to the beginning of March 2020 (ANCO 2020). This evolving EU market situation is being compounded by the closure of export markets for poultry producers in EU member states (AVEC 2020). Poland is one of the countries suffering the most. In the United States of America (USA), which exports a lot of chicken meat, the global export estimates for the chicken meat market have been cut due to emerging risks from the COVID-19 spread (USDA 2020). China's agriculture ministry has stated that the supply of chicken and egg losses of US$14.3 million (Clements 2020a, 2020b).

Egg prices have increased dramatically during the lockdown as consumers have started to change their behaviors and habits. Consumers had stockpiled necessary food items, including milk, eggs, and bread, to prepare for potential quarantines. Still, as lockdowns were introduced and people had to stay at home, actual consumption increased. People no longer eat out, so the demand for eggs is shifting from the foodservice sector to the retail channel, as consumers are cooking more meals at home (ANCO 2020). Egg consumption has also increased to replace more expensive protein forms in households that are seeing a decline in their income because of COVID-19–related job losses.

Hatcheries

The impact of the pandemic on poultry hatcheries has also been strong. The lockdown and the consequent limitation to the international poultry market have decreased the request for eggs to be used for incubation. Some governments have banned the import of poultry meat mainly to protect their internal market; this action has reduced general chicken placements by 15–25% (De Lange 2020). In Italy, several hatcheries have been forced to euthanize chickens and then reduce the number of incubated eggs (Tuttoggi 2020). If eggs are regularly sent to a hatchery, one way to reduce the number of incubated eggs is to prolong their storage at low temperatures. However, in the long term, this approach can harm hatchability and chick quality. Consequently, it might be better to reduce the number of eggs that enter hatchery, an action that is possible by culling old flocks and inducing forced molting in young flocks (De Lange 2020). Nevertheless, this approach reduces the cost of 1-day-old chickens: in Italy, the price has dropped by 35%.

Feed and food security

The availability of raw materials to prepare poultry feed has been strongly reduced by the COVID-19 pandemic in almost all countries, although the reasons are variable. The main ingredients in poultry feeds are corn and soybeans. The primary producers of corn are the USA, China, Brazil, and Argentina; the same countries also produce the most soy, albeit in a different order: the USA, Brazil, Argentina, and China. Thus, many countries around the world, dependent on imports for these raw materials, have had substantial problems in procuring the ingredients to prepare poultry feeds. In addition, about 65% of the net annual production of wheat, corn, and soybeans is used in the feed industry for farm animals, while the remaining 35% is used to meet human needs (All About Feed 2020a, 2020b). Thus, even though there has been an increase in grain consumption for human use, it has been unable to compensate for the losses tied to lowering animal feed production use (All About Feed 2020b; Berkhout 2020).

Furthermore, some agricultural sector activities are connected to migrant workers, who are stuck in their home countries due to lockdowns. Hence, the feed industries have lost a significant portion of their workforce (All About Feed 2020a). These factors have significantly impacted the global poultry sector (The Poultry Site 2020; Poudel et al. 2020).

Another possible risk in the next future is the concern about food safety and security. Even though it has been well established that poultry does not host COVID-19 and thus cannot transmit it to humans (Shi et al. 2020), most concerns are about intensive animal production that could amplify the threats of disease spread and emergence. The likelihood of outbreaks of high-impact animal diseases is elevated by the quarantine of many animals in limited zones, narrowed genetic diversity, and thus the increasing turnover of animals (CDC 2019; Tomley and Shirley 2009). Currently, there is no evidence that COVID-19 can be transmitted by food; however, the transmission is possible if an infected person touches food and another one, within a short time, touches the same food and then her or his mouth or eyes (CDC 2019; BfR 2020). Furthermore, the persistence of the virus at frozen temperatures has not been well described (CDC 2019), but other coronaviruses (e.g., MERS and SARS-CoV-1) can continue to pose a risk for up to 2 years in a frozen state (Hafez and Attia 2020). Thus, this pandemic must push poultry production to achieve several goals. First, the industry must move toward intensive production sustainability, especially by using modern technologies (precision poultry farming) or increasing extensive meat and egg production techniques. Second, the health and immune status of farmed poultry must be improved to increase their disease resistance. Third, feeding strategies must improve the content of poultry products of bioactive compounds that can stimulate the human immune defense (Parrish et al. 2008). Finally, high hygienic standards should be ensured through the entire food chain, from farm to fork. Impacts of COVID -19 on the global poultry sector is briefed in Fig. 3.

International poultry trade

The COVID pandemic might also substantially impact the international poultry trade over the next several months. For example, in the EU, many poultry meat (around 850,000 tons) is imported from developing countries, mainly Brazil, Thailand, and Ukraine, every year. Those imports are mainly destined for the foodservice market. However, to not lose their rights in the EU Tariff Rate Quota system, these countries continue to export poultry meat, even though the EU market does not demand it at the moment. Thus the meat is stored until the HORECA (hotel, restaurant, café) chains reopen. This action will result in a significant oversupply of poultry meat on the EU market in the weeks and months to come, with dangerous consequences on the price and quality of the products and future trade. On top of that, avian influenza outbreaks in Eastern Europe continue to hit hard in some countries (Poland, Hungary, and Romania). This issue has resulted in the closure of export markets in developing countries, driving this meat intended for exports back on the EU market and adding to the crisis (AVEC 2020; Parrish et al. 2008).

In conclusion, the possibility of poultry being infected by COVID-19 is remote, given that there is only a 60% genetic similarity between humans and chickens (Warren and Sawyer 2019). However, proper handling of animal products and safety measures should be taken during marketing and handling as a general role for all food supplies. Moreover, the possibility of the existence of COVID-19 in feedstuff and feed is not likely due to high temperature and pressure during feed processing. In addition, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the various poultry sectors such as slaughterhouses, broiler industry, table egg industry, hatcheries, and international poultry trade were favorable for the egg industry and adverse for the other sectors. Therefore, biosecurity, hygiene, and immunity have been and will remain the front line of defense during the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, developing and enhancing the current biosecurity measurements is essential to face the new emergence of diseases and overcome the unseen enemy after spreading the 2nd and the ongoing 3rd wave of COVID-19.

Data availability

The datasets used in this study are available in text and cited in the reference section.

References

Alagawany M, Attia YA, Farag MR, Elnesr SS, Nagadi SA, Shafi ME, Khafaga AF, Ohran H, Alaqil AA, El-Hack A, Mohamed E (2021) The strategy of boosting the immune system under the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Vet Sci 7:712

All About Feed (2020a) COVID-19: the impact on the animal feed industry https://www.allaboutfeed.net/Raw-Materials/Articles/2020/4/COVID-19-The-impact-on-theanimal-feed-industry-575937E. Accessed May 28, 2020a

All About Feed (2020b) Russia softens GMO import restrictions on soybeans. https://www.allaboutfeed.net/Raw-Materials/Articles/2020/5/Russia-softens-GMO-import-restrictions-on-soybeans-589359E/?utm_source=tripolis&utm_medium=email&utm_term=&utm_content=&utm_campaign=all_about_feed. Accessed May 28, 2020

Animal Nutrition Competence (ANCO). (2020) How are egg prices and egg producers responding to Covid 19. https://www.anco.net/how-are-egg-prices-and-egg-producers-responding-to-COVID-19/. Accessed June 12, 2020

Arcangeli G, Traversini V, Tomasini E, Baldassarre A, Lecca LI, Galea RP, Mucci N (2020) Allergic anaphylactic risk in farming activities: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17:4921. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17144921

Attia YA, El-Saadony MT, Swelum AA, Qattan SY, Al-Qurashi AD, Asiry KA, Shafi ME, Elbestawy AR, Gado AR, Khafaga AF, Hussein EO (2021) COVID-19: pathogenesis, advances in treatment and vaccine development and environmental impact—an updated review. Environ Sci poll Res:1–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-13018-1

BBC News (2020) Air pollution linked to raise COVID-19 death risk. https://www.bbc.com/news/health-52351290. Accessed June 15, 2020

Benjamin R (2020). Biosecurtity: what a lesson we are learning from COVID-19! https://www.wattagnet.com/blogs/25-latin-america-poultry-at-a-glance/post/39868-biosecurity-what-a-lesson-we-are-learning-from- COVID -19. Accessed June 14, 2020

Benseñor IM, Lotufo PA (2020) Some lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic virus. São Paulo Med J 138:174. https://doi.org/10.1590/1516-3180.2020.138320052020

Berkhout N (2020). Coronavirus: chickens are not susceptible. https://www.poultryworld.net/Health/Articles/2020/4/Coronavirus-Chickens-are-not-susceptible-573923E/?dossier=42157&widgetid=0. Accessed June 17, 2020

BfR (2020) Can the new type of coronavirus be transmitted via food and objects? https://www.bfr.bund.de/en/can_the_new_type_of_coronavirus_be_transmitted_via_food_and_ objects_-244090.html. Accessed June 10, 2020

Bolan NS, Szogi AA, Chuasavathi T, Seshadri B, Rothrock MJ Jr, Panneerselvam P (2010) Uses and management of poultry litter. World's Poult Sci J 66(4):673–698

Brown HC, Fu J. (2020) We’re mapping COVID-19-related slaughterhouse closures and re-openings. https://thecounter.org/mapping-COVID-19-related-slaughterhouse-closures-coronavirus/. Accessed June 18, 2020

Buonavoglia C, Decaro N, Martella V, Elia G, Campolo M, Desario C, Castagnaro M, Tempesta M (2006) Canine coronavirus highly pathogenic for dogs. Emerg Infect Dis 12:492

Capovilla M (2020) Venice’s famously-polluted canals clear as tourists stay away due to COVID-19. https://www.euronews.com/2020/03/16/venice-s-famously-polluted-canals-clear-as-tourists-stay-away-due-to-COVID -19. Accessed Month Day, Year

Center for Strategic International Studies (CSIS) (2020) COVID -19 and food security. What you need to know. https://www.csis.org/programs/global-food-security-program/COVID-19-and-food-security. Accessed June 15, 2020

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2019) Meat and poultry processing workers and employers https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/community/organizations/meat-poultry-processing-workers-employers.html. Accessed June 22, 2020

Chan JF, Lau SK, To KK, Cheng VC, Woo PC, Yuen KY (2015) Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus: another zoonotic betacoronavirus causing SARS-like disease. Clin Microbiol Rev 28:465–522

Chen Y, Guo Y, Pan Y, Zhao ZJ (2020) Structure analysis of the receptor binding of 2019-nCoV. Biochem Biophy Res Comm 525:135–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2020.02.071

Clarke K, Manrique A, Sabo-Attwood T, Coker ES (2021) A Narrative Review of Occupational Air Pollution and Respiratory Health in Farmworkers. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18:4097. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18084097

Clements M (2020a). How coronavirus is affecting China's poultry industry. https://www.wattagnet.com/articles/39761-how-coronavirus-is-affecting-chinas-poultry-industry. Accessed 3 Jun 2020

Clements M.. (2020b) Poultry around the world https://www.wattagnet.com/blogs/23-poultry-around-the-world/post/40146-what-poultry-producers-are-saying-about-the- COVID -19-outbreak. Accessed June 3, 2020

CNN (2020) 2 million chickens being killed because processing plants are short-staffed. https://www.thedenverchannel.com/news/national/coronavirus/2-million-chickens-being-killed-because-processing-plants-are-short-staffed. Accessed June 21, 2020

Colt J (2006) Water quality requirements for reuse systems. Aquacul Eng 34(3):143–156

Corrigan H (2020) Photos: clear skies and roaming wildlife abound in some of the world's most populated places. https://qz.com/1841716/coronavirus-stay-at-home-orders-decrease-global-pollution/. Accessed May 29, 2020

COVID-19 situation update worldwide (2020) https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/geographical-distribution-2019-ncov-cases. Accessed June 20, 2020

Das PK, Samanta I (2021) Role of backyard poultry in south-east Asian countries: post COVID-19 perspective. World's Poult Sci J:1–12

De Lange G (2020) Lessening the impact of prolonged hatching egg storage due to COVID-19. https://thepoultrysite.com/articles/lessening-the-impact-of-prolonged-hatching-egg-storage-due-to-COVID-19. Accessed June 8, 2020

Ding W, Levine R, Lin C, Xie W (2021) Corporate immunity to the COVID-19 pandemic. J Financ Econ 141:802–830

Durand-Moreau Q, Adisesh A, Mackenzie G, Bowley J, Straube S, Chan XH (2020) COVID-19 in meat and poultry facilities: a rapid review and lay media analysis. https://www.cebm.net/covid-19/what-explains-the-high-rate-of-sars-cov-2-transmission-in-meat-and-poultry-facilities-2/. Accessed December 6, 2020

European Poultry Producers Association (AVEC) (2020) The impact of the COVID 19 crisis on the EU poultry sector. April 21 2020. https://pluimvee.be/src/Frontend/Files/Core/CKFinder/files/2020_04_21%20The%20Impact%20of%20the%20COVID-19%20crisis%20on%20the%20Poultry%20Sector.pdf. Accessed June 20, 2020

Ficetola GF, Rubolini D (2020) Climate affects global patterns of Covid-19 early outbreak dynamics. MedRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.03.23.20040501

Friedrich-Loefler-Institut (FLI) (2020a) Federal Research Institute for Animal Health. Novel Coronavirus SARS-CoV-2: Fruit bats and ferrets are susceptible, pigs and chickens are not. https://www.fli.de/en/press/press-releases/press-singleview/novel-coronavirus-sars-cov-2-fruit-bats-and-ferrets-are-susceptible-pigs-and-chickens-are-not/. Accessed June 8, 2020

Friedrich-Loefler-Institut (FLI) (2020b) Federal Research Institute for Animal Health. Experimental infection of fruit bats, ferrets, pigs and chicken with SARS-CoV-2. https://www.fli.de/en/press/press-releases/press-singleview/novel-coronavirus-sars-cov-2-fruit-bats-and-ferrets-are-susceptible-pigs-and-chickens-are-not/. Accessed June 12, 2020

Fulton RW, Step DL, Wahrmund J, Burge LJ, Payton ME, Cook BJ, Burken D, Richards CJ, Confer AW (2011) Bovine coronavirus (BCV) infections in transported commingled beef cattle and sole-source ranch calves. Can J Vet Res 75:191–199

Galimberti A (2020) Poultry workers are frontline workers in the COVID-19 crisis. They are essential, not disposable. https://www.oxfamamerica.org/explore/stories/poultry-workers-are-frontline-workers- COVID -19-crisis-they-are-essential-not-disposable/. Accessed June 12, 2020

Hafez HM (2005) Governmental regulations and concept behind eradication and control of some important poultry diseases. World Poult Sci J 61:569–582. https://doi.org/10.1079/WPS200571

Hafez HM (2010). Poultry health-looking ahead to 2034. https://www.poultryworld.net/Broilers/Health/2010/7/Poultry-health%2D%2D-looking-ahead-to-2034-WP007651W/. Accessed May 5, 2020

Hafez MH, Attia YA (2020). Challenges to the poultry industry: current perspectives and strategic future after the COVID-19 outbreak. Front Vet Sci. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2020.00516

IEA (2020) International Energy Agency. Global oil demand to decline in 2020 as coronavirus weighs heavily on markets. https://www.iea.org/news/global-oil-demand-to-decline-in-2020-as-coronavirus-weighs-heavily-on-markets. Accessed June 10, 2020

Islam MS, Sobur MA, Akter M, Khmnh N, Toniolo A, Rahman MT (2020) Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, lessons to be learned. J Adv Vet Anim Res 7:260–280. https://doi.org/10.5455/javar.2020.g418

Kerr PJ, Donnelly TM (2013) Viral infections of rabbits. Vet Clin North Am Exot Anim Pract 16:437–468

La Regina M, Woods L, Klender P, Gaertner DJ, Paturzo FX (1992) Transmission of sialodacryoadenitis virus (SDAV) from infected rats to rats and mice through handling, close contact, and soiled bedding. Lab Anim Sci 42:344–346

Lai CC, Shih TP, Ko WC, Tang HJ, Hsueh PR (2020) Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19): The epidemic and the challenges. Int J Antimicrob Agents 55

Law S, Leung AW, Xu C (2020) Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19): from causes to preventions in Hong Kong. Int J Infect Dis 94:156–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.059

Lucheng Rn rat coronavirus in International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (2021). ICTV Master Species List 2019 v1. https://www.gbif.org/pt/species/159935549/verbatim. Accessed 7 Jul 2021

Luo J (2020) When will COVID-19 end? Data-driven prediction. https://www.persi.or.id/images/2020/data/Covid19_prediction_paper.pdf. Accessed may 15,2020

McDougal T (2020) Poultry plants in the US affected by COVID-19. https://www.poultryworld.net/Meat/Articles/2020/5/Poultry-plants-in-the-US-affected-by-Covid-19-580294E/?dossier=42157&widgetid=0. Accessed June 10, 2020

Middleton J, Reintjes R, Lopes H (2020) These businesses failed in their duty to workers and the wider public health. Br Med J 370:m2716. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m2716

Montanez AMR (2020a) Brazil: COVID-19 cases 2020, by state. Statista. 25/05/2020 https://www.statista.com/statistics/1103791/brazil-coronavirus-cases-state/. Accessed May 26, 2020

Montanez AMR (2020b) Brazil: COVID-19 cases and deaths. Statista. 25/05/2020. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1107028/brazil-covid-19-cases-deaths/. Accessed May 26, 2020

National Farmers Union (NFU) (2020) Coronavirus: what is the impact on the poultry sector? https://www.nfuonline.com/news/coronavirus-updates-and-advice/coronavirus-news/coronavirus-what-is-the-impact-on-the-poultry-sector/#Demand%20for%20poultry%20products. Accessed June 15, 2020

Onder G, Rezza G, Brusaferro S (2020) Case-fatality rate and characteristics of patients dying in relation to COVID-19 in Italy. JAMA 323:1775–1776. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.4683

Parrish CR, Holmes EC, Morens DM, Park E-C, Burke DS, Calisher CH, Laughlin CA, Saif LJ, Daszak P (2008) Cross-species virus transmission and the emergence of new epidemic diseases. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 72(3):457–470. https://doi.org/10.1128/MMBR.00004-08

Peszkô G (2020) Plastics: the coronavirus could reset the clock. https://blogs.worldbank.org/voices/plastics-coronavirus-could-reset-clock. Accessed May 30, 2020

Phan MVT, Tri TN, Anh PH, Baker S, Kellam P, Cotten M (2018) Identification and characterization of Coronaviridae genomes from Vietnamese bats and rats based on conserved protein domains. Virus Evol 4:35. https://doi.org/10.1093/ve/vey035

Poudel PB, Poudel MR, Gautam A, Phuyal S, Tiwari CK, Bashyal N et al (2020) COVID-19 and its global impact on food and agriculture. J Biol Todays World 9:221

Provacia LBV, Smits SL, Martina BE, Raj VS, vd Doel P, Amerongen GV, Moorman-Roest H, Osterhaus ADME, Haagmans BL, (2011) Enteric coronavirus in ferrets, The Netherlands. Emerg Infect Dis 17:1570

Pyrc K, Berkhout B, van der Hoek L (2007) The novel human coronaviruses NL63 and HKU1. J Virol 81:3051–3057

Rahman MT, Sobur MA, Islam MS, Toniolo A, Nazir K (2020) Is the COVID-19 pandemic masking dengue epidemic in Bangladesh? J Adv Vet Anim Res 7:218–219. https://doi.org/10.5455/javar.2020.g412

Rothan HA, Byrareddy SN (2020) The epidemiology and pathogenesis of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak. J Autoimmun 109:102433. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaut.2020.102433

Ruiz M (2020) An unintended consequence of COVID-19 shutdowns? Blue skies and cleaner air. https://www.vogue.com/article/coronavirus-environmental-impact-pollution. Accessed May 30, 2020

Saadat S, Rawtani D, Hussain CM (2020) Environmental perspective of COVID-19. Sci Total Environ 728:138870. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138870

Saghir SA, AlGabri NA, Alagawany MM, Attia YA, Alyileili SR, Elnesr SS, Shafi ME, Al-Shargi OY, Al-Balagi N, Alwajeeh AS, Alsalahi OS (2021) Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine for the prevention and treatment of COVID-19: a fiction, Hope or hype? An updated review. Therap Clinic Risk Manag 17:371–387

Sariol A, Perlman S (2020) Lessons for COVID-19 immunity from other coronavirus infections. Immunity 53:248–263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2020.07.005

Scalzaretto N (2020) World Health Organization suspends chloroquine trials. The Brazilian Report. https://brazilian.report/coronavirus-brazil-live-blog/. Accessed May 25, 2020

Schlottau K, Rissmann M, Graaf A, Schön J, Sehl J, Wylezich C, Höper D, Mettenleiter TC, Balkema-Buschmann A, Harder T, Grund C, Hoffmann D, Breithaupt A, Beer M (2020) SARS-CoV-2 in fruit bats, ferrets, pigs and chickens: an experimental transmission study. Lancet Microbe 1:218. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2666-5247(20)30089-6

Sharun K, Dhama K, Pawde AM, Gortázarc C, Ruchi T, Katterine B-AD, Rodriguez-Morales AJ, de la Fuente J, Michalak I, Attia YA (2021) SARS-CoV-2 in animals: potential for unknown reservoir hosts and public health implications. Vet Q 41(1):181–201. https://doi.org/10.1080/01652176.2021.1921311

Shereen MA, Khan S, Kazmi A, Bashir N, Siddique R (2020) COVID-19 infection: origin, transmission, and characteristics of human coronaviruses. J Adv Res 24:91–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jare.2020.03.005

Shi J, Wen Z, Zhong G, Yang H, Wang C, Huang B, Liu R, He X, Shuai L, Sun Z, Zhao Y, Liu P, Liang L, Cui P, Wang J, Zhang X, Guan Y, Tan W, Wu G, Chen H, Bu Z (2020) Susceptibility of ferrets, cats, dogs, and other domesticated animals to SARS–coronavirus. Science 368:1016–1020. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abb7015

Sykes J (2014) Feline coronavirus infection. In: Canine and feline infectious diseases. Saunders, p. 195

Taylor CA, Boulos C, Almond D (2020) Livestock plants and COVID-19 transmission. Proc Natl Acad Sci 117:31706–31715. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2010115117

Tenenbaum L (2020) The amount of plastic waste is surging because of the coronavirus pandemic. https://www.forbes.com/sites/lauratenenbaum/2020/04/25/plastic-waste-during-the-time-of-COVID -19/#1e87efb67e48. Accessed May 29, 2020

The Poultry Site (2020). 5 COVID-19 trends affecting backyard and commercial poultry. https://thepoultrysite.com/articles/5-covid-19-trends-affecting-backyard-and-commercial-poultry. Accessed June 16, 2020

Tokarz R, Sameroff S, Hesse RA, Hause BM, Desai A, Jain K, Ian Lipkin W (2015) Discovery of a novel nidovirus in cattle with respiratory disease. J Gen Virol 96:2188–2193. https://doi.org/10.1099/vir.0.000166

Tomley FM, Shirley MW (2009) Livestock infectious diseases and zoonoses. Philos Trans R Soc Lond Ser B Biol Sci 364:2637–2642. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2009.0133

Torremorell M, Bender J (2020) COVID-19: A biosecurity threat like nothing seen before. https://en.engormix.com/pig-industry/articles/COVID-biosecurity-threat-like-t45092.htm. Accessed June 10, 2020

Tratner I (2003) SRAS: 1 Le virus. M/S: Med Sci 19:885–891

Tuttoggi (2020) https://tuttoggi.info/cosi-il-coronavirus-mette-in-crisi-gli-agricoltori-in-umbria-tre-casi-regionali/562328/. Accessed June 7, 2020

United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) (2020) Foreign Agricultural Service April 9, 2020. https://apps.fas.usda.gov/psdonline/circulars/livestock_poultry.pdf. Accessed June 10, 2020

van der Made J (2020) Tsunami of plastic threatens post- COVID-19 world. http://www.rfi.fr/en/business/20200428-coronavirus-environment-plastic-increase-world-oil-production-crisis. Accessed June 10, 2020

Viegas S, Faísca VM, Dias H, Clérigo A, Carolino E, Viegas C (2013) Occupational exposure to poultry dust and effects on the respiratory system in workers. J Toxicol Environ Health A 76(4-5):230–239. https://doi.org/10.1080/15287394.2013.757199

Wang L, Byrum B, Zhang Y (2014) New variant of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus, United States, 2014. Emerg Infect Dis 20:917

Warren CJ, Sawyer SL (2019) How host genetics dictates successful viral zoonosis. PLoS Biol 17(4):e3000217. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3000217

Welshans K (2020) Meat sales, consumption surge amid COVID-19 disruption. https://www.supermarketnews.com/meat/meat-sales-consumption-surge-amid-COVID-19-disruption. Accessed June 22, 2020

World Health Organization (WHO) (2019) Middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV). https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/middle-east-respiratory-syndrome-coronavirus-(mers-cov). Accessed May 20, 2020

World Health Organization (WHO) (2020a). https://covid19.who.int/; 19. Accessed June 24, 2020

World Health Organization (WHO) (2020b) Water, sanitation, hygiene, and waste management for the COVID-19 virus. Interim guidance May 14 2020. (2020) https://apps.who.int/iris/rest/bitstreams/1272446/retrieve. Accessed June 5, 2020

Worldmeters (2020) Brazil – coronavirus cases. https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/country/brazil/. Accessed May 26, 2020

Zambrano-Monserrate MA, Ruano MA, Sanchez-Alcalde L (2020) Indirect effects of COVID-19 on the environment. Sci Total Environ 728:138813. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the financial support for publication provided by the Free University of Berlin (FUB), Germany.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HMH, YAA, FB, MEA, AFK and MCO were equally contributed to all stages of preparing, drafting, writing and revising this review article. All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work during different preparation stages. All authors read, revised and approved the final version of this manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics statement

As a review, this section may not be applicable.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Additional information

Responsible Editor: Lotfi Aleya

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hafez, H.M., Attia, Y.A., Bovera, F. et al. Influence of COVID-19 on the poultry production and environment. Environ Sci Pollut Res 28, 44833–44844 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-15052-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-15052-5