Abstract

This paper reviews the literature on agility and its relationship with organisational performance using a sample of 249 recent empirical studies from 1998 to February 2024. We find support for a relatively strong and consistent contribution of different aspects of agility to organisational performance. Our analysis highlights numerous salient issues in this literature in terms of the theoretical background, research design, and contextual factors in agility-performance research. On this basis, we propose relevant recommendations for future research to address these issues, specifically focusing on the role of the board of directors and their leadership in fostering organisational agility.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Since the “Manifesto for Agile Software Development” was declared in 2001 (Highsmith 2011), the Agility concept and methodologies have migrated from a narrow area of the IT industry to a wide range of organisational applications. Agility has often been associated with startups and small and medium-sized companies but has recently been extended to large corporations. Due to the volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous (VUCA) business environment combined with intense competition and threats from new startup radical growth, large firms are forced to change their status quo and their heavy and inflexible business and management models to quickly adapt to the rapidly changing environment. As such, embracing agility and leading with agility have become new norms and are essential for business survival (Rigby et al. 2016).

In recent years, the world economy has gone through unprecedented crises due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the tech and trade war between the US and China, the Ukraine-Russia war, and the most recent Gaza Strip conflict triggering the Red Sea marine crisis; this has intensified the need for organisations to develop more agile business models to weather environmental turbulence and economic downturns (McKinsey & Company 2020). Complexity and unpredictability are dominating rules, challenging traditional management methods that rely on well-order planning. As such, in today's business world, being agile is no longer optional—it is essential for a company to stay alive (Harraf et al. 2015).

The recent focus on organisational agility in both research and practice can also be tied to some common practices applied in both small and large companies. One example is the use of cross-functional teams with procedures such as SCRUM to work in harmony with customers and deliver what they expect in a timely and cost-efficient manner (Handscomb et al. 2019). Teams with members from different functions and disciplines work together to put customers first and respond swiftly to their requests, reducing the waiting time visible in hierarchal organisations. However, further research evidence is needed to examine whether and to what extent it is sufficient for such a practice to build organisational agility. This highlights the need for comprehensive literature reviews with scientific research insights to guide industry practitioners in the application of agile practices.

Organisational agility is often defined as the dynamic capability of an organisation to act and react to uncertainties and the ability to explore and exploit opportunities in the business environment (Overby et al. 2006; Roberts and Grover 2012). Since 2019, the number of publications on organisational agility in literature has increased notably. However, as this literature evolves, agility is conceptualised inconsistently. This is particularly problematic given that agility is a multidimensional concept that includes but is not limited to various aspects, such as manufacturing agility, strategic agility, supply chain agility, IT agility, marketing agility, and workforce agility (Walter 2021). Such disagreement among researchers regarding how agility should be defined and constructed has posed significant challenges for researchers and practitioners in this area moving forwards, making it difficult to build the literature upon previous findings, to generalise those findings in different contexts and to apply this concept in reality (Walter 2021). Thus, a comprehensive understanding of agility as an overarching concept, its antecedents, and its effects on organisational outcomes is needed (Walter 2021).

Agility is often considered beneficial to organisational performance. With a dynamic ability to weather rapid changes and turbulence, an agile organisation is believed to be in a better position to produce outcomes. However, some evidence shows that the organisational benefits of agility are dependent on a range of factors, including the types of agility and outcomes as the focus of interest and the conditions for agility to contribute to organisational outcomes (Wieland and Wallenburg 2012). For instance, agility is found to increase firm financial performance (Rafi et al. 2021) or boost innovation (Del Giudice et al. 2021). However, in their study, Chakravarty et al. (2013) found that only entrepreneurial agility—the proactive ability to anticipate and exploit market opportunities and challenges—can help achieve better financial performance, while such effects from reactive types of agility are not significant. Additionally, while researchers have devoted much attention to some aspects of agility, such as supply chain agility or strategic agility, other aspects of agility, such as workforce agility and marketing agility, are still underresearched (Ajgaonkar et al 2022; Gomes et al. 2020). This demonstrates the need for a comprehensive and systematic review of whether, how, and what agility can contribute to organisational outcomes.

Recent literature reviews in this area have elucidated how agility is measured, what contributes to agility and the impact of agility on organisational outcomes. However, these reviews either adopted a narrow focus on one aspect of agility, such as marketing agility, supply chain agility, or IT agility (Kalaignanam et al. 2021; Patel and Sambasivan 2021; Tallon et al. 2019), or failed to provide an in-depth analysis that focused exclusively on the contribution of agility to business outcomes (Walter 2021).

The lack of a consensus on the concept, measurements and association of organisational agility with critical business outcomes indicates the need for a systematic review of the literature to, first, bring together all different types of agility and examine their impact on different organisational outcomes; second, identify the intervening factors that affect this relationship; and third, provide implications for future research in this area. This paper addresses the abovementioned objectives with an overarching research question: What is the current status of the literature on organisational agility and organisational outcomes? Then, this question is broken down into five broad subquestions as follows:

-

How are organisational agility and organisational performance defined and measured?

-

What is the relationship between organisational agility and organisational outcomes?

-

Which theories are used to examine the relationship between organisational agility and organisational outcomes?

-

What are some possible mediators or moderators that affect the relationship between organisational agility and organisational outcomes?

-

What are the implications for future research on this topic?

To comprehensively review the literature on agility and organisational performance, this paper adopts the strategy of a systematic literature review to examine 249 empirical studies in this area from 1998 to February 2024. This paper makes two significant contributions to the literature in this field. First, it seeks to provide a comprehensive summary and a conceptual map of whether and how organisational agility affects organisational performance based on 26 years of empirical evidence on this topic. Second, it aims to identify the gaps in knowledge and propose possible directions for future research and practices in this area. The paper starts with an introduction of the research design, followed by a description of the research findings, and ends with a discussion and recommendations for future research.

2 Research design

This paper adopts the widely used systematic review methodology in literature review studies to collect and analyse data because it is comprehensive, transparent, evidence-based, and unbiased (Khan et al. 2003; Snyder 2019; Tranfield et al. 2003). Figure 1 explains the strategy and steps taken to conduct this literature review.

Following Xiao and Watson (2019), Diaz Tautiva et al. (2024), Tranfield et al. (2003), the paper utilises a systematic strategy and review steps through the three main phases of (i) planning, (ii) data collection, and (iii) data extraction, synthesis, and reporting to ensure the replicability and transparency of the methodology and findings. In the planning phase, we formed the review framework by carefully crafting the research objectives and referring to existing systematic review frameworks. Through this process, we were able to determine the search criteria and the framework for data extraction and classification, as indicated in Fig. 1.

The review framework is based on dimensions of agility, variable measurement, theoretical background, methodology, findings, and intervening factors, followed by a synthesis of a conceptual map (Walter 2021; Bhattacharjee and Sarkar 2022; Patel and Sambasivan 2021). This framework is well aligned with our research questions and objectives and is often used in other literature review papers (Walter 2021; Bhattacharjee and Sarkar 2022; Patel and Sambasivan 2021). By using this framework, we can then move to the next step, which involves identifying the knowledge gaps in the literature and proposing some directions for future research in the field.

Using the predetermined search criteria identified in the planning phase, we first conducted a general search on Web of Science, one of the largest coverage databases, and obtained a sample of 8107 papers. We used the filter function to include 1165 peer-reviewed articles that had full texts available, were written in English, and were published in the fields of business, economics, and management. Then, we screened the titles and abstracts and adopted further exclusion criteria, as shown in Fig. 1. The final sample consists of 249 English peer-reviewed empirical articles on agility and organisational outcomes, with agility being one of the main variables of interest in studies that test the firm-level impact of agility in the business, economics, and management fields.

Three groups of coders performed the data extraction and grouping based on the predetermined criteria mentioned above. Discussion and moderation were conducted before each group carried out their tasks. The data were extracted into an Excel file and categorised into the following columns: article title, authors, year, journal, theories, sample size, sample type (cross-sectional or panel), independent variables, moderators and contextual variables, mediators, dependent variables, control variables, analytical approach, and findings.

3 Research findings

3.1 Descriptive analysis

Table 1 summarises some key features of our data. In this dataset, agility is either the primary independent variable or a mediator that links inputs to outcomes. We also included other recent literature reviews and conceptual papers in this field to support our data analysis. Thus, our final data consist of 249 empirical studies, 39 literature reviews and conceptual studies, and seven other relevant studies in this area.

Figure 2 presents the distribution of 249 empirical studies on agility and outcomes from 1998 to February 2024, with a sharp increase in the number of publications in recent years since 2017. This indicates researchers’ growing interest in this area and reflects a timely research response to recent environmental and societal changes (Joyce 2021).

Table 2 provides an overview of different subtopics in agility and organisational outcomes research and shows that supply chain agility, organisational agility, and strategic agility are the most researched topics in this area. Other aspects of agility run from manufacturing/operational to marketing, business process, customer, workforce, IT and digital, market capitalising, project management, leadership, intellectual, R&D, social media, and value creation.

3.2 Measuring agility

Table 3 elucidates how different types of agility are measured in the literature. There is no consensus on how agility should be defined and measured. As the most researched type of agility, supply chain agility has been captured based on one or multiple dimensions, such as customers, products, delivery, responsiveness to the environment, competitors, and partners (Mandal 2018; Charles et al. 2010), collaborative planning (Braunscheidel and Suresh 2009; Chiang et al. 2012), procurement/sourcing and distribution/logistics (Swafford et al. 2006). Other approaches to measuring agility focus more on organisational capabilities such as alertness, accessibility, decisiveness, swiftness, and flexibility (Gligor and Holcomb 2012) or internal processes such as network collaboration, information integration, process integration, customer demand responsiveness (Mirghafoori et al. 2017) or information sharing (Whitten et al. 2012).

Organisational agility has also been measured in different ways. While some pioneering studies consider organisational agility to be flexible (Sharifi and Zhang 1999), others reveal that organisational agility should be a broader concept (Vokurka and Fliedner 1998). Such a concept can be similar to organisational ambidexterity (Overby et al. 2006; Roberts and Grover 2012), can feature dynamic capability (Teece et al. 1997), or can represent an overall organisational framework (Doz and Kosonen 2008; Dyer and Shafer 1998). The three most popular dimensions of organisational agility—customers, operation and partnership—are drawn from the work of Tallon and Pinsonneault (2011). Other approaches capture the sensing capability and response capability of organisations (Overby et al. 2006) or have different focuses, including but not limited to internal capabilities (Sharifi and Zhang 1999), people (Pramono et al. 2021), business processes (Vaculík et al. 2018), or products and costs (Zheng et al. 2023).

Strategic agility is commonly measured based on strategic sensitivity, resource fluidity, leadership unity, or a combination of technology capability, collaborative innovation, organisational learning, and internal alignment (Clauss et al. 2021; Doz and Kosonen 2008). Another approach involves adopting the three key dimensions of agility from Tallon and Pinsonneault (2011) from a strategic perspective. Some other measurement approaches are presented in Table 3.

Manufacturing agility has been examined as a system leveraged by a range of capabilities, including responsiveness, competency, flexibility and speed (Cao and Dowlatshahi 2005; Sharifi and Zhang 1999), or as an organisational competency (Jacobs et al. 2011). Some of the less popular types of agility, such as customer agility, are measured as customers’ sensing capabilities and customers’ response capabilities (Clauss et al. 2021; Doz and Kosonen 2008). Intellectual agility is captured as the level of business-related skills, the frequency of skills and knowledge updates, the perception of work tasks as a challenge or an opportunity to practice skills, and the willingness to apply alternative solutions when solving problems (Chen and Chiang 2011; Felipe et al. 2016; Sambamurthy et al. 2003).

Overall, the literature on agility offers a wide range of approaches to measuring organisational agility and other dimensions of agility. While traditional approaches such as those of Sharifi and Zhang (1999), Overby et al. (2006), or Tallon and Pinsonneault (2011) are widely used, the literature continues to evolve with newer and more innovative approaches to measure agility and its dimensions. On the one hand, it motivates researchers in this field to develop better and more comprehensive ways to capture agility. On the other hand, the lack of consistency in measuring agility makes it difficult for researchers to synthesise how agility and its dimensions are constructed and what organisations should focus on to be more agile. Thus, there is a lack of informed guidance for practitioners to build agility in their organisations.

3.3 Measuring organisational outcomes

Table 4 provides an overview of the various aspects of organisational outcomes and the ways in which they are measured. The literature indicates a wide range of organisational outcomes examined in the context of agility. Some popular approaches to measuring organisational outcomes include the use of a self-reported overall organisational performance indicator, the construction of a composite variable with multiple dimensions, or the use of multiple separate indicators to capture different aspects of performance, including but not limited to financial performance (accounting and market indicators), nonfinancial performance, environmental performance, operational performance and beyond (Kurniawan et al. 2021a, b). Other aspects of organisational outcomes examined in the agility and organisational outcomes literature include supply chain performance, innovation, competitiveness, customer service performance, digital and technology performance, manufacturing and operation, sustainability, international performance, employees, marketing, and organisational capabilities.

The literature offers a diverse set of organisational outcomes in conjunction with agility. This allows researchers and practitioners to look at how agility affects organisations in different angles and layers from financial performance to organisational survival, operation, sustainability, capabilities, employee performance and well-being. However, methodologically, the literature reveals some flaws in measuring and constructing organisational performance. While the predominant use of composite variables helps capture an overall indicator of organisational performance, which eases the analysis process (Panda 2021), this approach lacks consideration of the separate impact of each aspect of performance, making it challenging to interpret the results and apply the findings to practice.

The literature also reveals that organisational outcomes are often measured as construct variables through reflective/self-report survey questions (Altay et al. 2018; Goncalves et al. 2020), which raises some concerns about data reliability and validity. Some other studies use quantitative variables based on secondary data (Gligor and Bozkurt 2021; Pereira et al. 2021) or examine both qualitative and quantitative performance variables. However, further tests should be adopted to ensure the consistency and congruence of these methods (Feizabadi et al. 2019; Gligor et al. 2020a, b).

3.4 The use of theories in agility and organisational outcome research

Table 5 provides a summary of relevant theories in this area of research. Despite the wide range of theories available in this domain, the use of theories in empirical research in this sample is still inadequate. Out of 249 empirical studies, 141 (56.6%) adopt single or multiple theoretical approaches to build their argument of the contribution of agility to organisational outcomes. However, 109 (43.8%) studies in the dataset did not explicitly utilise relevant theories to support their hypothesis development. Given this lack of solid theoretical frameworks, these studies cannot develop a logical and established view of how or why agility improves organisational outcomes, which might threaten the rigour of their research design and the strength of their argument.

Furthermore, Table 5 highlights a wide range of theories incorporated in this research domain, with the dynamic capabilities perspective and the resource-based view being the most widely used theoretical background. These two theoretical frameworks are often combined to provide a comprehensive understanding of the relationship between agility and outcomes (Jabarzadeh et al. 2022; Mikalef and Pateli 2017). The dynamic capabilities perspective emphasises the importance of perceiving and seizing valuable growth opportunities and the ability to transform the organisation to fit with these opportunities (Teece et al. 1997). However, the dynamic capabilities perspective is criticised for its limited explanation of how and to what extent organisations should achieve the abovementioned purposes (Ambler and Wilson 2006). The resource-based view focuses on analysing the internal resources of the enterprise as well as linking internal resources with the external environment to foster innovation and create competitive advantage (Sambamurthy et al. 2003). However, similar to dynamic capabilities theory, the resource-based view still has limited practicality (El Shafeey and Trott 2014). Therefore, future studies on firm performance and agility should be based on a multitheoretical approach to obtain a more comprehensive view of this relationship (Doz and Kosonen 2008; Dyer and Shafer 1998).

3.5 The relationship between agility and organisational performance

Figure 3 summarises the findings of the relationship between agility and performance. Evidence from the current literature elucidates the positive impact of agility on organisational performance, with 219 (87.9%) studies confirming the positive impact of different forms of agility on organisational outcomes. Twenty-seven studies reported mixed effects between agility and organisational outcomes, 2 studies found no significant relationship between agility and organisational outcomes, and 1 study showed a negative impact of organisational agility on the continuity of innovation projects in organisations.

Overall, relatively strong and consistent results support the contribution of organisational agility to organisational outcomes, including overall organisational performance (Stei et al. 2024), financial and nonfinancial performance (i.e., Rafi et al. 2021), innovation (i.e., Goncalves et al. 2020), sustainability ( i.e., Lopez-Gamero et al. 2023), competitiveness (i.e., Mikalef and Pateli 2017), digital and technology transformation ( i.e., Ly 2023), international performance ( i.e., Nemkova 2017), and employee job performance ( i.e., Chung et al. 2014).

However, some studies still report mixed effects of organisational agility on organisational outcomes. Several factors contribute to this mixed effect. First, it depends on the type of inputs and outcomes in the models where organisational agility serves as a mediator or a main independent variable. For example, even though organisational agility is found to enhance radical innovation, it does not help incremental innovation, even under technological turbulence, according to a study conducted by Puriwat and Hoonsopon (2021). Organisational agility has been shown to translate firm knowledge management into competitive advantage. However, by taking a closer look at different forms of knowledge management, Corte-Real et al. (2017) found that organisational agility serves as a mediator only for the relationship between exogenous knowledge management and firm competitiveness but not for that between endogenous knowledge management or knowledge sharing partners. Another study confirmed that knowledge management improves organisational agility, which in turn strengthens firm competitive advantage, but a similar positive mediating effect is not found for knowledgement and firm innovation (Salimi and Nazarian 2022).

Second, the impact of organisational agility on organisational outcomes is dependent on its dimensions. For instance, between the two types of organisational agility, entrepreneurial agility improves firm financial performance, while adaptive agility does not (Chakravarty et al. 2013). Additionally, El Idrissi et al. (2023) found that among the three dimensions of organisational agility—customer agility, operational agility, and partnering agility—only the first two help organisations to be more prepared for crises.

Third, the mixed effect of organisational agility on organisational outcomes is found under different contextual factors. For instance, the dynamics of the business environment facilitate the positive effect of organisational agility on firm financial performance but not on environmental performance or social performance (Khan 2023). Under a low to moderate level of industry competition, organisational agility positively mediates the impact of operational cooperation on the mass customisation of products and services. However, when competition is too intense, this mediating effect becomes negative (Sheng et al. 2021). Vaculík et al. (2018) found that under disruptive organisational changes, firms need to trade off short-term benefits for long-term performance. In such a situation, being more agile causes firms to abandon their current innovation projects and leads to greater possibilities of innovation project termination.

Supply chain agility has been found to improve organisational financial performance (DeGroote and Marx 2013, Wamba and Akter 2019; Zhu and Gao 2021), competitive advantage (Alfalla-Luque et al. 2018; Chen 2019), commercial performance (Sturm et al. 2021), customer service (Avelar 2018), customer satisfaction (Gligor et al. 2020a, b), supply chain performance (Baah et al. 2021; Wang and Ali 2021), and supply chain resilience (Naimi et al. 2020). However, in some specific situations, such as uncertain environmental conditions and supply chain disruptions, only supply chain flexibility—one of the three dimensions of supply chain agility—increases organisational performance, while the impacts of the other two dimensions (velocity and visibility) are not statistically significant (Juan et al. 2021). Another study showed that supply chain agility has no significant impact on performance (Wieland and Wallenburg 2012).

Strategic agility has been found to directly improve overall performance (Chan and Muthuveloo 2021; Kurniawan et al. 2020), project performance (Haider and Kayani 2021), technological performance (Pereira et al. 2021), competitive advantage (Hemmati et al. 2016), and innovation (Clauss et al. 2021). However, Reed (2021) shows that under environmental turbulence, firms that are more strategically agile experience lower financial performance.

Manufacturing agility and operational agility have been proven to increase competitiveness (Vázquez‐Bustelo et al. 2007), manufacturing performance (Awan et al. 2021), and market share (Ettlie 1998). However, Jacobs et al. (2011) found that the relationship between manufacturing and firm financial performance is not significant.

Strong evidence supports the contribution of other forms of agility to organisational outcomes (Abrishamkar et al. 2021; Asseraf et al. 2019b; Gupta et al. 2019; Ju et al. 2020; Roberts and Grover 2012). However, the positive contributions of these forms vary under certain conditions. Onngam and Charoensukmongkol (2023) highlighted that firms benefit more from social media agility when the organisational size is smaller and the dynamism of the business environment is lower. Sharif et al. (2022) found that market capitalising agility only mediates the relationship between knowledge coupling and firm innovation during business downsizing. Khan (2020) and Zhou et al. (2019) noted that marketing agility improves firm financial performance. However, when the market is turbulent, this positive effect becomes nonsignificant; when the complexity of marketing is heightened, higher marketing agility reduces marketing adaptation ability. Ngo and Vu (2021, 2020) examined two dimensions of customer agility and found that while sensing capability helps organisations achieve superior financial performance, response capability does not.

Overall, the literature on the organisational impact of agility provides strong evidence to support such a positive and significant effect. However, in some cases, how and whether agility leads to higher outcomes is notably dependent on (i) certain environmental factors, (ii) different dimensions of agility and (iii) the types of organisational outcomes.

3.6 Intervening factors in organisational agility and outcomes relationship

Table 6 presents the use of intervening factors in agility and performance research. Agility is often treated as an important mediator linking organisational inputs to outcomes. This is reflected in 61.8% of the research in the dataset incorporating agility as a mediator in their models. For instance, organisational agility is considered a positive explanatory factor for the impact of technological capability and IT (Govuzela and Mafini 2019), corporate network management (Kurniawan et al. 2021a, b), knowledge and intellectual resources management (Cegarra-Navarro et al. 2016), leadership capability (Oliveira et al. 2012b, a), risk management culture (Liu et al. 2018), organisational learning culture (Pantouvakis and Bouranta 2017), strategic alignment (Hazen et al. 2017), promotion information analysis capability (Shuradze et al. 2018), organisational ambidexterity (Del Giudice et al. 2021), and dispute management (Yaseen et al. 2021) on organisational performance. This indicates the importance of conducting agility-performance research in an organisation's internal and external context to understand how agility plays out with other factors to predict organisational outcomes.

Table 7 presents the types of intervening factors examined in the literature on agility and organisational outcomes. The literature highlights that the organisational impact of agility is subjected to a wide range of moderating factors. As aforementioned, organisational agility tends to exert its strengths under adverse environmental conditions, such as volatile and complex environments (Clauss et al. 2021), high competitive pressure (Ahammad et al. 2021), and high demand for major technological change in the industry (Ashrafi et al. 2019). Additionally, the impact of agility on organisational outcomes depends on external factors such as customer loyalty (Gligor et al. 2020b, a) and industry type (Lee et al. 2016) or internal factors such as firm age (Reed 2021), the adaptability of products and marketing (Asseraf et al. 2019a), the nature of work (Chung et al. 2014), information technology systems agility (Tallon and Pinsonneault 2011), and startup innovation sensitivity (Tsou and Cheng 2018).

Third, the literature also elucidates the mediators through which agility contributes to organisational outcomes. These include but are not limited to the following: new technology acceptance (Chung et al. 2014), business model innovation (Mihardjo and Rukmana 2019), entrepreneurship and innovative behaviour development (Pramono et al. 2021), networking structure (Yang and Liu 2012) and market and social media analytics capability (Yang and Liu 2012). Similarly, supply chain agility is said to improve organisational performance through competitiveness (Sheel and Nath 2019), risk management (Okoumba et al. 2020), collaboration and re-engineering capabilities (Abeysekara et al. 2019), effectiveness, cost reduction (Gligor et al. 2015), and customer value and customer service (Um 2017).

The above analysis and the aspects that are mentioned in Sect. 3.5 stress the importance of studying the relationship between agility and firm performance in the context of both contextual factors and mediators. This highlights the need for future research to continue searching for factors that affect the contribution of agility to firm performance. Such comprehensive models will enhance our understanding of the relationship between agility and organisational performance and, as such, will significantly contribute to further developing this research area.

3.7 Research methodologies in the agility and firm performance literature

Table 8 presents a summary of popular research methodologies used in agility–organisational outcome research, with several notable findings as follows:

First, most studies in the sample use quantitative methods to examine the effect of agility on firm performance. Qualitative and mixed methods, although considered insightful and comprehensive (Truscott et al. 2010), have not been adequately utilised in this literature. Overall, the quantitative approach is appropriate for testing the causal effect between Agility (X) and OP (Y) in one or multiple regression models. However, the over-emphasis on causality testing without a proper investigation of the underlying reasons and insights using qualitative techniques might lead to imprecise findings and conclusions, which may create confusion and misunderstanding when applied to practice (Heyvaert et al. 2013).

Second, the research on agility and organisational performance mainly uses primary data from surveys and questionnaires to individuals and organisations at a specific timeframe. This approach is appropriate because, given the complexity of measuring agility, it is challenging and impractical for researchers to use proxy and secondary data for measurement. However, using a one-time survey has disadvantages in terms of reliability and generalisability, as the information collected only reflects the impact of agility on organisational performance at a specific time point. This reduces the generalisability of research findings to other contexts at different time points (Bartram 2019; Wooldridge 2010).

Third, the most popular analytical tool used in this literature is structural equation modelling (SEM)/PLS-SEM (Mikalef and Pateli 2017; Ramos et al. 2021), which includes bootstrapping techniques (Felipe et al. 2020; Gligor et al. 2019), followed by multiregression approaches for cross-sectional or panel data (Chen et al. 2014; Pereira et al. 2021). It is appropriate to use SEM for complex models with multilevel causal relationships. This method facilitates the examination of models with different pathways, including models with mediators and moderators, and provides suitable treatments for latent variables (Bollen 2014; Kline 2015).

Notably, there are two widely used methods in SEM: covariance-based SEM (CB-SEM) and partial least squares-based SEM (PLS-SEM). CB-SEM is often used in confirmatory research and factor-based models, while PLS-SEM is used in exploratory research and composite-based models (Dash and Paul 2021; Rigdon et al. 2017). However, the use of PLS-SEM is still debatable in the literature. PLS-SEM is criticised for its limited ability to examine complex and multidirectional causal relationships in SEM and its unproven assumptions (Antonakis et al. 2010). This leads to inconsistency in analytical findings and the ability to appraise model fit, especially for models based on small sample sizes (McIntosh et al. 2014; Rönkkö et al. 2016). Recent research in this area has emphasised that researchers must prioritise understanding their research question, the nature of the variables used, and the purpose of their research to consider the appropriate analytical method (Sarstedt et al. 2016).

4 Discussion and implications for future research

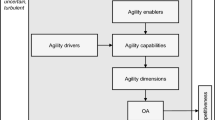

Using a dataset of 249 empirical studies from 1998 to 2024, this literature review paper has highlighted that agility is an essential predictor of organisational outcomes. Details about agility, firm performance, and the intervening factors of this causal relationship are summarised in Fig. 4. The findings of this paper support our understanding of the relationship between agility and organisational performance and provide valuable implications for future research in this field, as indicated below.

4.1 Measuring agility

The literature shows that organisational agility is a matter of becoming rather than being (Alzoubi, et al. 2011; Harraf et al 2015). As analysed earlier, the literature on agility and firm performance has not provided a solid answer as to how and to what extent agility and its dimensions should be measured. For instance, Table 2 indicates that organisational agility can be measured with multiple instruments, including a firm’s internal capability, external partnership management, its proactiveness to sensing new opportunities, and its responsiveness to changes in the environment. This provides opportunities for future research to explore more extensive approaches to measuring agility based on the literature and explore how organisational agility and its dimensions could be improved (i.e., Ajgaonkar et al. 2022).

4.2 Theoretical background

Our analysis indicates that there is a wide range of theories available in the literature that provide explanations and justifications for the contribution of agility to organisational performance, with dynamic capability theory and resource-based theory being the two most widely used theories. The literature also highlights the growing use of multitheoretical approaches for a more extensive understanding of this relationship. Future research could explore new theories and simultaneously continue to incorporate multiple theories to examine the relationship between agility and firm performance.

4.3 Agility dimensions and their impacts on organisational performance

Our analysis indicates that organisational agility, supply chain agility, strategic agility, and manufacturing/operational agility are the most popular topics in the agility-firm performance literature, while the organisational impact of other types of agility, for instance, workforce agility, intellectual agility, leadership agility, and project management agility, are not thoroughly examined. This provides opportunities for future research to investigate these dimensions and their impact on organisational outcomes.

Another promising pathway moving forwards is leadership agility. While top managers and corporate boards are considered crucial for creating and promoting organisational agility, research on this topic is still scarce in terms of both quantity and quality (Lehn 2018). The existing corporate governance literature has emphasised the unparalleled contribution of boards of directors to organisational survival with their ability to link firms to external resources during economic uncertainties, crises, or bankruptcy (Haleblian and Finkelstein 1993; Hillman et al. 2009). To do so, boards needs to build their dynamic capabilities to create, strengthen, and adjust their internal resources to adapt to the external environment (Barreto 2010; Helfat et al. 2009). However, except for the work of Desai (2016) that examines the impact of board size and ownership structure on organisational flexibility and the work of Hoppmann et al. (2019) on the influence of the board on strategic flexibility, this area of research is still in its infancy. This gap in knowledge encourages future research to examine (i) the processes that allow boards to fulfil their role of facilitating changes and building agility capability in their organisation, (ii) the attributes and characteristics of boards that allow them to be more agile, and (iii) whether such agility can contribute to organisational agility, which translates to organisational outcomes.

Our literature review also indicates that agility can contribute to a wide range of organisational outcomes. However, there is still a lack of evidence on how agility affects outcomes in an orderly way running from the individual level to the group level to organisational level outcomes and how and whether the impact of agility on organisational outcomes might be different in the short, medium, and long term. Thus, it is strongly recommended that future research explore these possibilities to provide a more comprehensive and structured view of agility and outcome relationships.

4.4 Interactions and intervening factors

Our review indicates that many aspects of organisational performance benefit from agility. However, these benefits are likely to be dependent on a wide range of factors. This encourages future research to continue searching for intervening factors that have meaningful impacts on the agility–performance relationship. For instance, how and whether agility impacts organisational outcomes might depend on various factors: the type of organisation – small and medium-sized enterprises, public sector organisations, multinational enterprises, nonprofit organisations or domestic vs. international organisations; different stages of the organisational life cycle; and different types of organisational structure and culture (Harraf et al 2015).

Additionally, different types of agility may interact, and such interactions might affect organisational outcomes in different ways. This warrants further investigation to examine the effects of different types of agility on firm performance both separately and interactively (Gunasekaran et al 2019), for instance, the interactive effects of workforce agility and manufacturing agility on organisational performance.

4.5 Methodology

Our review shows that quantitative research is a primary approach in agility-firm performance research. However, the overreliance on causality might prevent researchers from understanding the underlying reasons why agility can translate to organisational outcomes and the dynamics behind this causal relationship. As such, future research should use a mixed method with both qualitative and quantitative approaches to first understand the organisational impact of agility at the surface level and, second, reveal the processes, dynamics, blockages, enablers and other organisational factors that explain the relationship between agility and organisational outcomes.

Additionally, our review indicates that there is still a lack of comparative research in this area. This provides some pathways for future research to investigate the effect of agility on firm performance in comparative settings. For instance, is the impact of agility on organisational outcomes different across different national cultures and institutional contexts?

Finally, our review highlighted the need for panel and time series data to examine the short-term, medium-term, and long-term effects of agility on organisational performance. We strongly recommend that future research develop more extensive datasets covering multiple periods to ensure that robust and rigorous studies are added to this literature.

4.6 Implications

The resulting concept model of this paper with antecedents, mediators, moderators, organisational outcomes and types of agility has multiple implications for industry practitioners.

First, organisational agility is constructed from several subcomponents corresponding to multiple business functions, such as the supply chain, strategy, manufacturing, marketing, workforce, IT and leadership. For an entire organisation to be agile, each and every function should be agile.

Organisations can utilise different avenues and practices to build capabilities that contribute to agility.

Second, agility promotes corporate outcomes through its impact on mediating actions. To realise the potential of agility, organisations should account for those mediating steps and outcomes in their implementation.

Finally, a strong finding of this literature review is the way in which the relationship between agility and outcomes is contextualised. As such, organisations should pay attention to both internal and external environments as contingent factors on agility and outcomes. For instance, agility seems to have the greatest impact in complex and volatile environments, so organisations should carefully consider the implementation of agility if they operate in relatively stable industries. Additionally, while startups in high-tech industries are initially agile, established businesses in stable industries are generally not agile. As such, for such businesses to achieve agility, they should consider factors such as firm size, IT infrastructure and their customer base.

5 Research contribution, limitations and conclusion

By answering the research question “What is the current status of the literature on organisational agility and organisational outcomes?” in the above analysis, this study has provided a comprehensive picture of the current literature on the relationship between several aspects of agility and firm performance, with the former either as independent or as mediator variables. The review covers theories, measurements, relationship structure, methodology, and concepts of agility. Following Walter's (2021) systematic review of agility, our study has extended the scope of investigation and focuses specifically on the relationship between the two most important concepts of agility and performance that play a minor role in Walter’s OA conceptual map. Additionally, the paper has mapped out the organisational agility–performance relationship with antecedents, mediators and moderators, each with a specific list of dimensions for measurement, as sketched out in the subresearch questions. This conceptual map can guide future studies in establishing well-rooted research models.

With a limited number of empirical studies (249), a sharp increase since 2017, a few with archival data (while a majority with data from questionnaires and interviews), and a significant proportion of research without theories as background, agility performance appears to be an emerging research field in its immature phase. This point is strengthened by the fact that the reviewed articles are not in top theoretical management journals such as the Journal of Management and the Academy of Management Journal. Furthermore, theories of this relationship have not been explicitly developed to support quantitative studies for hypothesis testing. By highlighting this gap, this study opens a new road for researchers to establish theories for the agility–performance relation beyond what is currently borrowed from the strategic management field.

Our paper has several limitations. Our attempt to provide a comprehensive overview of agility and performance prevents us from examining this relationship in a specific country or industry context. In addition, although our dataset covers a long time frame from 1998 to February 2024, some of the most recent research may not be included in our review. Nevertheless, we believe that our findings underline both the importance of organisational agility and the worth viewing it in conjunction with other organisational aspects in predicting organisational performance. Furthermore, we hope that this study will inspire future investigations to move further in this literature.

In conclusion, organisational agility and its association with organisational performance have emerged as attractive research topics since 2017. Even though quantitative empirical studies account for most publications, a significant number of them lack a background theory and a consensus on measuring agility and its subcategories. This is detrimental to the value of the findings and intensifies the need for future studies to develop this immature field.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from Web of Science database for account holders. The data are available from the authors upon request.

References

Abdelilah B, El Korchi A, Balambo M (2021) Agility as a combination of lean and supply chain integration: how to achieve a better performance. Int J of Logistics-Res Appl. https://doi.org/10.1080/13675567.2021.1972949

Abeysekara N, Wang H, Kuruppuarachchi D (2019) Effect of supply-chain resilience on firm performance and competitive advantage: A study of the Sri Lankan apparel industry. Bus Process Manag J 25(7):1673–1695. https://doi.org/10.1108/BPMJ-09-2018-0241

Abrishamkar MM, Abubakar YA, Mitra J (2021) The influence of workforce agility on high-growth firms: the mediating role of innovation. Int J Entrepren Innov 22(3):146–160. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465750320973896

Jahed AM, Quaddus M, Suresh NC, Salam MA, Khan EA (2022) Direct and indirect influences of supply chain management practices on competitive advantage in fast fashion manufacturing industry. J Manuf Technol Manag 33(3):598–617. https://doi.org/10.1108/jmtm-04-2021-0150

Adhiatma A, Hakim A, Fachrunnisa O, Hussain FK (2024) The role of social media business and organizational resources for successful digital transformation. J Media Bus Stud 21(1):23–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/16522354.2023.2203641

Agag G, Shehawy YM, Almoraish A, Eid AR, Lababdi HC, Labben TG, Abdo SS (2024) Understanding the relationship between marketing analytics, customer agility, and customer satisfaction: A longitudinal perspective. J Retail Consumer Serv. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2023.103663

Agarwal A, Shankar R, Tiwari MK (2007) Modeling agility of supply. Ind Mark Manag 36(4):443–457. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2005.12.004

Ahammad MF, Basu S, Munjal S et al (2021) Strategic agility, environmental uncertainties and international performance: The perspective of Indian firms. J World Bus 56(4):101218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2021.101218

Ahmed W, Najmi A, Mustafa Y, Khan A (2019) Developing model to analyze factors affecting firms’ agility and competitive capability: A case of a volatile market. J Model Manag 14(2):476–491. https://doi.org/10.1108/JM2-07-2018-0092

Ajgaonkar S, Neelam NG, Wiemann J (2022) Drivers of workforce agility: a dynamic capability perspective. Int J Org Anal 30(4):951–982

Akhtar P, Ghouri AM, Saha M, Khan MR, Shamim A, Nallaluthan K (2022) Industrial digitization, the use of real-time information, and operational agility: digital and information perspectives for supply chain resilience. Ieee Trans Eng Manag. https://doi.org/10.1109/tem.2022.3182479

Akter S, Hani U, Dwivedi YK, Sharma A (2022) The future of marketing analytics in the sharing economy. Ind Marketing Manag 104:85–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2022.04.008

Al Humdan E, Shi YY, Behina M, Chowdhury M, Mahmud A (2023) The role of innovativeness and supply chain agility in the Australian service industry: a dynamic capability perspective. Int J Phys Dist & LogistManag 53(11):1–25. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijpdlm-03-2022-0062

Aldhaheri RT, Ahmad SZ (2023) Factors affecting organisations’ supply chain agility and competitive capability. Bus Process Manag J 29(2):505–527. https://doi.org/10.1108/bpmj-11-2022-0579

Alfalla-Luque R, Machuca JA, Marin-Garcia JA (2018) Triple-A and competitive advantage in supply chains: Empirical research in developed countries. Int J Prod Econ 203:48–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2018.05.020

Alghamdi O, Agag G (2024) Competitive advantage: A longitudinal analysis of the roles of data-driven innovation capabilities, marketing agility, and market turbulence. J Retail Consumer Serv. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2023.103547

Alhassani AA, Al-Somali S (2022) The impact of dynamic innovation capabilities on organizational agility and performance in Saudi Public Hospitals. Risus-J Innov Sustain 13(1):44–59. https://doi.org/10.23925/2179-3565.2022v13i1p44-59

Ali A, Rafiq A, Hussien M, Sarwat S, Raziq A (2023) Exploring big data usage to predict supply chain effectiveness: a moderated and mediated model linkage. Glob Bus Rev. https://doi.org/10.1177/09721509231183767

Alkhatib SF, Momani RA (2023) Supply chain resilience and operational performance: the role of digital technologies in Jordanian manufacturing firms. Admin Sci 13(2):40. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci13020040

Al-Qaralleh RE, Atan T (2021) Impact of knowledge-based HRM, business analytics and agility on innovative performance: linear and FsQCA findings from the hotel industry. Kybernetes 51(1):423–441. https://doi.org/10.1108/K-10-2020-0684

Al-Shboul MA (2017) Infrastructure framework and manufacturing supply chain agility: the role of delivery dependability and time to market. Int J Supply Chain Manag 22(2):172–185. https://doi.org/10.1108/scm-09-2016-0335

Al-Shboul MA, Alsmairat MAK (2023) Enabling supply chain efficacy through SC risk mitigation and absorptive capacity: an empirical investigation in manufacturing firms in the Middle East region - a moderated-mediated model. Supply Chain Manag-an Int J 28(5):909–922. https://doi.org/10.1108/scm-09-2022-0382

Alsmairat MAK, Al-Shboul MA (2023) Enabling supply chain efficacy through supply chain absorptive capacity and ambidexterity: empirical study from Middle East region-a moderated-mediation model. J Manu Techn Manag 34(6):917–936. https://doi.org/10.1108/jmtm-10-2022-0373

AlTaweel IR, Al-Hawary SI (2021) The mediating role of innovation capability on the relationship between strategic agility and organizational performance. Sustainability 13(14):7564. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13147564

Altay N, Gunasekaran A, Dubey R, Childe SJ (2018) Agility and resilience as antecedents of supply chain performance under moderating effects of organizational culture within the humanitarian setting: a dynamic capability view. Prod Plan Control 29(14):1158–1174. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537287.2018.1542174

Alzahrani SS (2023) Balanced agile project management impact on firm performance through business process agility as mediator in IT sector of Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Int J Bus PerformManag 24(3–4):409–428. https://doi.org/10.1504/ijbpm.2023.132326

Alzoubi AEH, Al-otoum FJ, Albatainh AKF (2011) Factors associated affecting organization agility on product development. Int J Res Rev in Applied Sci 9(3):503–515

Ameen N, Tarba S, Cheah JH, Xia SM, Sharma GD (2024) Coupling artificial intelligence capability and strategic agility for enhanced product and service creativity. British J Manag. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.12797

Antonakis J, Bendahan S, Jacquart P, Lalive R (2010) On making causal claims: a review and recommendations. Leadersh Q 21(6):1086–1120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2010.10.010

Arslan AS, Kamara S, Tian AY, Rodgers P, Kontkanen M (2024) Marketing agility in underdog entrepreneurship: A qualitative assessment in post-conflict Sub-Saharan African context. J Bus Res. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2023.114488

Aryanto VDW, Mulyo BS (2018) Mediating effect of value creation in the relationship between relational capabilities on business performance. Contaduría y admin 63(1):0–0

Ashrafi A, Ravasan AZ, Trkman P, Afshari S (2019) The role of business analytics capabilities in bolstering firms’ agility and performance. Int J Inf Manag 47:1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2018.12.005

Aslam H, Khan AQ, Rashid K, Rehman S-u (2020) Achieving supply chain resilience: the role of supply chain ambidexterity and supply chain agility. J Manuf Technol Manag 31(6):1185–1204. https://doi.org/10.1108/jmtm-07-2019-0263

Asseraf Y, Lages LF, Shoham A (2019) Assessing the drivers and impact of international marketing agility. Int Mark Rev 36(2):289–315. https://doi.org/10.1108/imr-12-2017-0267

Avelar L (2018) Application of structural equation modelling to analyse the impacts of logistics services on risk perception, agility and customer service level. Adv Prod Eng Manag 13(2):179–192. https://doi.org/10.14743/apem2018.2.283

Awan U, Bhatti SH, Shamim S et al (2021) the role of big data analytics in manufacturing agility and performance: moderation-mediation analysis of organizational creativity and of the involvement of customers as data analysts. Br J Manag 33(3):1200–1220. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.12549

Baah C, Agyeman DO, Acquah ISK et al (2021) Effect of information sharing in supply chains: understanding the roles of supply chain visibility, agility, collaboration on supply chain performance. Benchmarking Int J. https://doi.org/10.1108/BIJ-08-2020-0453

Babber G, Mittal (2023) Achieving sustainability through the integration of lean, agile, and innovative systems: implications for Indian micro small medium enterprises (MSMEs). J Sci Technol Polic Manag. https://doi.org/10.1108/jstpm-05-2023-0087

Barreto I (2010) Dynamic capabilities: A review of past research and an agenda for the future. J Manag 36(1):256–280. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206309350776

Bartram B (2019) Using questionnaires. In: Lambert M (ed) Practical research methods in education. Routledge, p 1–11. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351188395

Bhattacharjee A, Sarkar A (2022) Abusive supervision: a systematic literature review. Manag Rev Q 74(1):1–34

Bhatti SH, Santoro G, Khan J, Rizzato F (2021) Antecedents and consequences of business model innovation in the IT industry. J Bus Res 123:389–400. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.10.003

Bollen KA (2014) Structural equations with latent variables, vol 210. John Wiley & Sons, New Jersey

Bouguerra A, Gölgeci İ, Gligor DM, Tatoglu E (2021) How do agile organizations contribute to environmental collaboration? Evidence from MNEs in Turkey. J Int Manag 27(1):100711. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intman.2019.100711

Braunscheidel MJ, Suresh NC (2009) The organizational antecedents of a firm’s supply chain agility for risk mitigation and response. J Oper Manag 27(2):119–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2008.09.006

Bughin J (2023) Are you resilient? Machine learning prediction of corporate rebound out of the Covid-19 pandemic. Manag Decis Econ 44(3):1547–1564. https://doi.org/10.1002/mde.3764

Cadden T, McIvor R, Cao GM, Treacy R, Yang Y, Gupta M, Onofrei G (2022) Unlocking supply chain agility and supply chain performance through the development of intangible supply chain analytical capabilities. Int J Operations & Prod Manag 42(9):1329–1355. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijopm-06-2021-0383

Cao Q, Dowlatshahi S (2005) The impact of alignment between virtual enterprise and information technology on business performance in an agile manufacturing environment. J Oper Manag 23(5):531–550. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2004.10.010

Castro-Lopez A, Iglesias V, Santos-Vijande ML (2023) Organizational capabilities and institutional pressures in the adoption of circular economy. J Bus Res. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2023.113823

Cegarra-Navarro J-G, Soto-Acosta P, Wensley AKP (2016) Structured knowledge processes and firm performance: The role of organizational agility. J Bus Res 69(5):1544–1549. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.10.014

Çetindas A, Akben I, Özcan C, Kanusagi I, Öztürk O (2023) The effect of supply chain agility on firm performance during COVID-19 pandemic: the mediating and moderating role of demand stability. Supply Chain Forum 24(3):307–318. https://doi.org/10.1080/16258312.2023.2167465

Cha H, Park SM (2023) Organizational agility and communicative actions for responsible innovation: evidence from manufacturing firms in South Korea. Asia Pac J Manag. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-023-09883-8

Chakravarty A, Grewal R, Sambamurthy V (2013) Information technology competencies, organizational agility, and firm performance: Enabling and facilitating roles. Inf Syst Res 24(4):976–997

Chan JIL, Muthuveloo R (2021) Antecedents and influence of strategic agility on organizational performance of private higher education institutions in Malaysia. Stud High Educ 46(8):1726–1739. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1703131

Chan JIL, Muthuveloo R (2022) Strategic agility: linking people and organisational performance of private higher learning institutions in Malaysia. Int J Bus Soc 23(1):342–358. https://doi.org/10.33736/ijbs.4616.2022

Chan JLL, Muthuveloo R (2019) Antecedents and influence of strategic agility on organizational performance of private higher education institutions in Malaysia. Stud High Educ. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1703131

Charles A, Lauras M, Van Wassenhove L (2010) A model to define and assess the agility of supply chains: building on humanitarian experience. Int J Phys Dist Logist Manag 40(8/9):722–741. https://doi.org/10.1108/09600031011079355

Chatterjee S, Chaudhuri R, Vrontis D (2022) Examining the impact of adoption of emerging technology and supply chain resilience on firm performance: moderating role of absorptive capacity and leadership support. Ieee Trans on Eng Manag. https://doi.org/10.1109/tem.2021.3134188

Chen C-J (2019) Developing a model for supply chain agility and innovativeness to enhance firms’ competitive advantage. Manag Decis 57(7):1511–1534. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-12-2017-1236

Chen W-H, Chiang A-H (2011) Network agility as a trigger for enhancing firm performance: A case study of a high-tech firm implementing the mixed channel strategy. Ind Mark Manag 40(4):643–651. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2011.01.001

Chen Y, Wang Y, Nevo S et al (2014) IT capability and organizational performance: the roles of business process agility and environmental factors. Eur J Inf Syst 23(3):326–342. https://doi.org/10.1057/ejis.2013.4

Cherian TM, Arun CJ (2023) COVID-19 impact in supply chain performance: a study on the construction industry. Int J Prod Perform Manag 72(10):2882–2897. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijppm-04-2021-0220

Chiang C-Y, Kocabasoglu-Hillmer C, Suresh N (2012) An empirical investigation of the impact of strategic sourcing and flexibility on firm’s supply chain agility. Int J Oper Prod 32(1–2):49–78. https://doi.org/10.1108/01443571211195736

Cho HE, Jeong I, Kim E, Cho J (2023) Achieving superior performance in international markets: the roles of organizational agility and absorptive capacity. J Bus Ind Mark 38(4):736–750. https://doi.org/10.1108/jbim-09-2021-0425

Christopher M, Peck H (2004) Building the Resilient Supply Chain. Int J Logist Manag 15(2):1–14. https://doi.org/10.1108/09574090410700275

Chuang SH (2020) Co-creating social media agility to build strong customer-firm relationships. Ind Mark Manag 84:202–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2019.06.012

Chung S, Lee KY, Kim K (2014) Job performance through mobile enterprise systems: The role of organizational agility, location independence, and task characteristics. Inf Manag 51(6):605–617. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2014.05.007

Clauss T, Abebe M, Tangpong C, Hock M (2021) Strategic Agility, Business Model Innovation, and Firm Performance: An Empirical Investigation. IEEE Trans Eng Manag 68(3):767–784. https://doi.org/10.1109/tem.2019.2910381

Corte-Real N, Oliveira T, Ruivo P (2017) Assessing business value of big data analytics in European firms. J Bus Res 70:379–390. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.08.011

Dabić M, Stojčić N, Simić M, Potocan V, Slavković M, Nedelko Z (2021) Intellectual agility and innovation in micro and small businesses: The mediating role of entrepreneurial leadership. J Bus Res 123:683–695

Dahms S, Cabrilo S, Kingkaew (2023) Configurations of innovation performance in foreign owned subsidiaries: focusing on organizational agility and digitalization. Manag Decis. https://doi.org/10.1108/md-05-2022-0600

Das KP, Mukhopadhyay S, Suar D (2023) Enablers of workforce agility, firm performance, and corporate reputation. Asia Pac Manag Rev 28(1):33–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmrv.2022.01.006

Dash G, Paul J (2021) CB-SEM vs PLS-SEM methods for research in social sciences and technology forecasting. Technol Forecast Soc Change 173:121092. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2021.121092

de Oliveira MA, Oliveira Dalla Valentina LV, Possamai O (2012a) Forecasting project performance considering the influence of leadership style on organizational agility. Int J Product Perform Manag 61(6):653–671. https://doi.org/10.1108/17410401211249201

DeGroote SE, Marx TG (2013) The impact of IT on supply chain agility and firm performance: An empirical investigation. Int J Inf Manag 33(6):909–916

Del Giudice M, Scuotto V, Papa A et al (2021) A self-tuning model for smart manufacturing SMEs: effects on digital innovation. J Prod Innov Manag 38(1):68–89. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpim.12560

Desai VM (2016) The behavioral theory of the (governed) firm: Corporate board influences on organizations’ responses to performance shortfalls. Acad Manag J 59(3):860–879. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2013.0948

Dhaigude A, Kapoor R (2017) The mediation role of supply chain agility on supply chain orientation-supply chain performance link. J Decis Syst 26(3):275–293. https://doi.org/10.1080/12460125.2017.1351862

Diaz T, Andrés J, Rivera FIR, Celume SAB, Rivera SAR (2024) Mapping the research about organisations in the latin american context: a bibliometric analysis. Manag Rev Q 74(1):121–169

Doz Y, Kosonen M (2008) The dynamics of strategic agility: Nokia’s rollercoaster experience. Calif Manag Rev 50(3):95–118. https://doi.org/10.2307/41166447

Drury-Grogan ML (2014) Performance on agile teams: Relating iteration objectives and critical decisions to project management success factors. Inf Softw Technol 56(5):506–515. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infsof.2013.11.003

Dubey R, Singh T, Gupta OK (2015) Impact of agility, adaptability and alignment on humanitarian logistics performance: mediating effect of leadership. Glob Bus Rev 16(5):812–831. https://doi.org/10.1177/0972150915591463

Dyer L, Shafer RA (1998) From human resource strategy to organizational effectiveness: lessons from research on organizational agility. https://ecommons.cornell.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/ff207b12-5936-48df-899e-3ea1fb07a2f6/content

Eckstein D, Goellner M, Blome C, Henke M (2015) The performance impact of supply chain agility and supply chain adaptability: the moderating effect of product complexity. Int J Prod Res 53(10):3028–3046. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207543.2014.970707

Eisele S, Greven A, Grimm M, Fischer-Kreer D, Brettel M (2022) Understanding the drivers of radical and incremental innovation performance: The role of a firm’s knowledge-based capital and organisational agility. Int J InnovManag. https://doi.org/10.1142/s1363919622500207

El Idrissi M, El Manzani E, Maatalah WA, Lissaneddine Z (2023) Organizational crisis preparedness during the COVID-19 pandemic: an investigation of dynamic capabilities and organizational agility roles. Int J Org Anal 31(1):27–49. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijoa-09-2021-2973

El Shafeey T, Trott P (2014) Resource-based competition: three schools of thought and thirteen criticisms. Eur Bus Rev 26(2):122–148. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-07-2013-0096

Engström TE, Westnes P, Westnes SF (2003) Evaluating intellectual capital in the hotel industry. J Intellect Cap 4(3):287–303. https://doi.org/10.1108/14691930310487761

Ettlie JE (1998) R&D and global manufacturing performance. Manag Sci 44(1):1–11. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.44.1.1

Fadaki M, Rahman S, Chan C (2020) Leagile supply chain: design drivers and business performance implications. Int J Prod Res 58(18):5601–5623. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207543.2019.1693660

Fang MJ, Liu F, Xiao SF, Park K (2023) Hedging the bet on digital transformation in strategic supply chain management: a theoretical integration and an empirical test. Int J Phys Dist Logist Manag 53(4):512–531. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijpdlm-12-2021-0545

Feizabadi J, Gligor D, Motlagh SA (2019) The triple-As supply chain competitive advantage. Benchmarking Int J 26(7):2286–2317. https://doi.org/10.1108/BIJ-10-2018-0317

Felipe CM, Leidner DE, Roldan JL, Leal-Rodriguez AL (2020) Impact of IS capabilities on firm performance: the roles of organizational agility and industry technology intensity. Decis Sci 51(3):575–619. https://doi.org/10.1111/deci.12379

Felipe CM, Roldán JL, Leal-Rodríguez AL (2016) An explanatory and predictive model for organizational agility. J Bus Res 69(10):4624–4631. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.04.014

Franco C, Landini F (2022) Organizational drivers of innovation: The role of workforce agility. Res Pol 51(2):104423. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2021.104423

Ganguly A, Talukdar A, Kumar C (2024) Absorptive capacity and disruptive innovation: the mediating role of organizational agility. Ieee Trans Eng Manag 71:3117–3128. https://doi.org/10.1109/tem.2022.3205922

Gligor D, Bozkurt S (2021) The role of perceived social media agility in customer engagement. J Res Interact Mark 15(1):125–146

Gligor DM, Holcomb MC (2012) Antecedents and consequences of supply chain agility: establishing the link to firm performance. J Bus Logist 33(4):295–308. https://doi.org/10.1111/jbl.12003

Gligor D, Bozkurt S, Gölgeci I, Maloni MJ (2020a) Does supply chain agility create customer value and satisfaction for loyal B2B business and B2C end-customers? Int J Phys Distrib 50(7/8):721–743. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPDLM-01-2020-0004

Gligor D, Esmark CL, Holcomb MC (2015) Performance outcomes of supply chain agility: When should you be agile? J Oper Manag 33–34:71–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2014.10.008

Gligor D, Feizabadi J, Russo I et al (2020b) The triple-a supply chain and strategic resources: developing competitive advantage. Int J Phys Distrib 50(2):159–190. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPDLM-08-2019-0258

Gligor D, Holcomb M, Maloni MJ, Davis-Sramek E (2019) Achieving financial performance in uncertain times: leveraging supply chain agility. Transp J 58(4):247–279. https://doi.org/10.5325/transportationj.58.4.0247

Gomes E, Sousa CMP, Vendrell-Herrero F (2020) International marketing agility: conceptualization and research agenda. Int Mark Rev 37(2):261–272

Goncalves D, Bergquist M, Bunk R, Alänge S (2020) Cultural aspects of organizational agility affecting digital innovation. Int J Entrepren Innov 16(4):13–46. Retrieved from https://www.ceeol.com/search/article-detail?id=909079

Govuzela S, Mafini C (2019) Organisational agility, business best practices and the performance of small to medium enterprises in South Africa. S Afr J Bus Manag 50(1):1–3. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajbm.v50i1.1417

Gunasekaran A, Yusuf YY, Adeleye EO et al (2019) Agile manufacturing: an evolutionary review of practices. Int J Prod Res 57(15–16):5154–5174

Guo RP, Yin HB, Liu X (2023) Coopetition, organizational agility, and innovation performance in digital new ventures. Ind Mark Manag 111:143–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2023.04.003

Gupta S, Kumar S, Kamboj S et al (2019) Impact of IS agility and HR systems on job satisfaction: an organizational information processing theory perspective. J Knowl Manag 23(9):1782–1805. https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-07-2018-0466

Hadjielias E, Christofi M, Christou P, Drotarova MH (2022) Digitalization, agility, agility, and customer value in tourism. Technol Forecast Soc Ch. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2021.121334

Haider SA, Kayani UN (2021) The impact of customer knowledge management capability on project performance-mediating role of strategic agility. J Knowl Manag 25(2):298–312. https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-01-2020-0026

Haleblian J, Finkelstein S (1993) Top management team size, CEO dominance, and firm performance: The moderating roles of environmental turbulence and discretion. Acad Manag J 36(4):844–863. https://doi.org/10.5465/256761

Hallgren M, Olhager J (2009) Lean and agile manufacturing: external and internal drivers and performance outcomes. Int J Oper Prod Manag 29(10):976–999

Handscomb C, Heyning C, Woxholth J (2019). Giants can dance: Agile organizations in asset-heavy industries. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/oil-and-gas/our-insights/giants-can-dance-agile-organizations-in-asset-heavy-industries

Harraf A, Wanasika I, Tate K, Talbott K (2015) Organizational agility. J Appl Bus Res 31(2):675–686

Hazen BT, Bradley RV, Bell JE et al (2017) Enterprise architecture: a competence-based approach to achieving agility and firm performance. Int J Prod Econ 193:566–577. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2017.08.022

Helfat CE, Finkelstein S, Mitchell W et al (2009) Dynamic capabilities: Understanding strategic change in organizations. John Wiley & Sons, New Jersey

Hemmati M, Feiz D, Jalilvand MR, Kholghi I (2016) Development of fuzzy two-stage DEA model for competitive advantage based on RBV and strategic agility as a dynamic capability. J Model Manag 11(1):288–308. https://doi.org/10.1108/JM2-12-2013-0067

Heyvaert M, Hannes K, Maes B, Onghena P (2013) Critical appraisal of mixed methods studies. J Mix Methods Res 7(4):302–327. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689813479449

Highsmith J (2011). History: The Agile Manifesto. https://agilemanifesto.org/

Hillman AJ, Withers MC, Collins BJ (2009) Resource dependence theory: a review. J Manag 35(6):1404–1427. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206309343469

Hoppmann J, Naegele F, Girod B (2019) Boards as a source of inertia: examining the internal challenges and dynamics of boards of directors in times of environmental discontinuities. Acad Manag J 62(2):437–468. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2016.1091

Huma S, Ahmed W (2022) Understanding influence of supply chain competencies when developing Triple-A. Benchmarking Int J 29(9):2757–2779. https://doi.org/10.1108/bij-06-2021-0337

Hwang T, Kim ST (2019) Balancing in-house and outsourced logistics services: effects on supply chain agility and firm performance. Serv Bus 13(3):531–556

Ilmudeen A (2021) Information technology (IT) governance and IT capability to realize firm performance: enabling role of agility and innovative capability. Benchmarking Int J. https://doi.org/10.1108/bij-02-2021-0069

Ismail H, Sharifi H (2006) A balanced approach to building agile supply chains. Int J Phys Distrib 36(6):431–444. https://doi.org/10.1108/09600030610677384

Jabarzadeh Y, Khangah MH, Cemberci M, Cerchione R, Sanoubar N (2022) Effect of absorptive capacity on strategic flexibility and supply chain agility: implications for performance in fast-moving consumer goods. Oper Supply Chain Manag Int J 15(3):407–423

Jacobs M, Droge C, Vickery SK, Calantone R (2011) Product and process modularity’s effects on manufacturing agility and firm growth performance. J Prod Innov Manag 28(1):123–137. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5885.2010.00785.x

Jing ZC, Zheng Y, Guo HL (2023) A study of the impact of digital competence and organizational agility on green innovation performance of manufacturing firms-the moderating effect based on knowledge inertia. Admin Sci 13(12):250. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci13120250

Joiner B (2019) Leadership agility for organizational agility. J Creat Value 5(2):139–149. https://doi.org/10.1177/2394964319868321

Joyce P (2021) Public governance, agility and pandemics: a case study of the UK response to COVID-19. Int Rev Adm Sci 87(3):536–555. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020852320983406

Ju X, Ferreira FA, Wang M (2020) Innovation, agile project management and firm performance in a public sector-dominated economy: Empirical evidence from high-tech small and medium-sized enterprises in China. Soci-Econ Plan Sci 72:100779. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seps.2019.100779

Juan S-J, Li EY, Hung W-H (2021) An integrated model of supply chain resilience and its impact on supply chain performance under disruption. Int J Logist Manag 33(3):339–364. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJLM-03-2021-0174

Kalaignanam K, Tuli KR, Kushwaha T et al (2021) keting agility: The concept, antecedents, and a research agenda. J Mark 85(1):35–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022242920952760

Kareem MA, Kummitha HVR (2020) The impact of supply chain dynamic capabilities on operational performance. Organizacija. https://doi.org/10.2478/orga-2020-0021

Khan KS, Kunz R, Kleijnen J, Antes G (2003) Five steps to conducting a systematic review. J R Soc Med 96(3):118–121. https://doi.org/10.1177/014107680309600304

Khan AN (2023) Artificial intelligence and sustainable performance: role of organisational agility and environmental dynamism. Technol Anal Strateg Manag. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537325.2023.2290171

Khan A, Talukder MS, Islam QT, Islam A (2022) The impact of business analytics capabilities on innovation, information quality, agility and firm performance: the moderating role of industry dynamism. Vine J Inf and Knowl Manag Syst. https://doi.org/10.1108/vjikms-01-2022-0027

Khan H (2020) Is marketing agility important for emerging market firms in advanced markets? Int Bus Rev 29(5):101733. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2020.101733

Khan NA, Ahmed W, Waseem M (2023) Factors influencing supply chain agility to enhance export performance: case of export-oriented textile sector. Rev Int Bus Strateg 33(2):301–316. https://doi.org/10.1108/ribs-05-2021-0068

Kline RB (2015) Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford Publications, New York

Ko A, Mitev A, Kovács T, Fehér P, Szabo Z (2022) Digital agility, digital competitiveness, and innovative performance of SMEs. J Compet 14(4):78–96. https://doi.org/10.7441/joc.2022.04.05

Kocoglu I, Keskin H, Cemberci M, Civelek ME (2022) Effect of supply chain coordination on performance: a serial mediation model of trust, agility, and collaboration. Int J Inf Sys Supply Chain Manag. https://doi.org/10.4018/ijisscm.287130

Ku ECS, Chen CD (2023) Increasing the organizational performance of online sellers: the powerful back-end management systems. Bus Process Manag J 29(3):838–857. https://doi.org/10.1108/bpmj-11-2022-0562

Kurniawan R, Budiastuti D, Hamsal M, Kosasih W (2020) The impact of balanced agile project management on firm performance: the mediating role of market orientation and strategic agility. Rev Int Bus Strategy 30(4):457–490. https://doi.org/10.1108/RIBS-03-2020-0022

Kurniawan R, Budiastuti D, Hamsal M, Kosasih W (2021a) Networking capability and firm performance: the mediating role of market orientation and business process agility. J Bus Ind Mark 36(9):1646–1664. https://doi.org/10.1108/jbim-01-2020-0023

Kurniawan R, Manurung AH, Hamsal M, Kosasih W (2021b) Orchestrating internal and external resources to achieve agility and performance: the centrality of market orientation. Benchmarking Int J 28(2):517–555. https://doi.org/10.1108/bij-05-2020-0229

Kustyadji G, Windijarto W, Wijayani A (2021) Ambidexterity and leadership agility in micro, small and medium enterprises (MSME)’s performance: an empirical study in Indonesia. J Asian Fin Econ Bus 8(7):303–311. https://doi.org/10.13106/jafeb.2021.vol8.no7.0303

Lago NC, Marcon A, Ribeiro JLD, Olteanu Y, Fichter K (2023) The role of cooperation and technological orientation on startups’ innovativeness: An analysis based on the microfoundations of innovation. Technol Forecast Soc Change. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2023.122604