Abstract

The institutional distance between home and host countries influences the benefits and costs of entry into markets where a firm intends to conduct business. Entry mode choice is a function of a firm's strategy to increase its competitiveness, efficiency, and control over resources that are critical to its operations. This systematic literature review aims to explain the influence of institutional distances on equity-based entry modes in international markets. The present study contributes to the literature on international business using institutional theory to address the entry mode, and by analyzing the nature of the constructs used to measure the influence institutional distances have on the choice of entry mode into foreign markets.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The decision to enter international markets is a central research topic in International Business (IB) (Shen et al. 2017; Werner 2002). The literature on entry mode choice has made significant progress, and has recently shifted its focus towards an institutional perspective (Adamoglou and Kyrkilis 2018). A recent literature review of articles on the determinants of equity ownership in decisions to enter foreign markets revealed that in over 60% of cases, institutional theory was used to support their studies (Chhabra et al. 2021).

Institutions play a significant role in IB as they affect a firm’s capacity to interact with the players in a new market and influence the relative transaction and coordination costs of production and ownership decisions in a particular location (e.g., Dunning and Lundan 2008; Henisz and Delios 2001). The mainstream in this literature (North 1990; Scott 2014) showed that institutions impact strategic decisions. That being so, a considerable body of research has investigated how and to what extent this impact occurs, notably by introducing the concept of 'institutional distance' in the IB literature (Kostova and Zaheer 1999). This concept has gained prominence since then (Aguillera and Grogaard 2019).

Scholars have devoted attention to investigating the influence of distance on the location decision and entry mode choice (Berry et al. 2010; Dow and Larimo 2009; Tihanyi et al. 2005), and on the ownership strategy in the host country (Chikhouni et al. 2017; Delios and Henisz 2003; Dunning and Lundan 2008; Peng 2003). Berry et al. (2010) highlighted the importance of defining and measuring cross-country distances in their multiple dimensions and showed that different distance types could affect management decisions in several ways, depending on the dimension examined. Focusing on national distances from an institutional perspective allows us to capture the diversity of ways in which countries differ (Pajunen 2008).

While prior empirical studies made considerable progress in this subject and showed the importance of considering institutional distance with regard to equity-based entry modes, our literature review has revealed scant IB research on combining both perspectives. Most reviews focused exclusively on institutional perspectives (Kostova et al. 2020), distances (Beugelsdijk et al. 2018a, b; Cuypers et al. 2018), or entry mode (Klier et al. 2017; Shen et al. 2017).

This study aimed to review and systematize the existing literature on the influence of institutional distances on equity entry modes. Thus, this review will address the choice between acquisition and greenfield and the ownership strategy that includes joint ventures and wholly owned subsidiaries as well as studies that analyze partial and total ownership of MNC subsidiaries in foreign markets. It goes beyond Kostova et al. (2020) by reviewing other frameworks to analyze the influence that distances (i.e., perceptual and objective) have on decisions involving entry mode.

This study addresses the sociological (Scott 2014) and the economic (North 1990) perspectives of institutional theory and other frameworks on distances and entry modes. Our purpose is to shed more light on the fundamentals, dimensions, and institutional factors that affect the choice of entry mode. To this end, the research question is: How has recent research conceptualized and tested the impact of institutional distance on the choice of the equity-based entry mode?

The present study intends to contribute to the IB literature on entry mode and the interface with institutions in two ways. First, it aims to clearly show how the various dimensions of institutional distances proposed in the literature are related and how they influence entry mode. Second, this study expands existing knowledge about the role institutions play in equity-based entry mode decisions and ownership choice in foreign markets, to thus produce a more comprehensive picture of the institutional dimensions and how they are used in institutional distance research. Synthesis of the collected studies allowed us to identify some gaps in the literature and to proffer suggestions for future research that we believe will increase our knowledge in IB, specifically regarding the institutional dimensions and their interfaces with the entry mode literature.

This article is structured as follows: the next section presents our research strategy, the selection criteria and the template used for coding and analyzing the literature; in Sect. 3, we address the theoretical streams that researchers have used to support entry mode studies; Sect. 4 deals with institutional distances and shows how the construct has been conceptualized and operationalized; in Sect. 5, we comment on the main findings; and finally in Sect. 6, we present the research agenda and the limitations of our study.

2 Methodology

The method chosen for this systematic review followed the directives proposed by Petticrew and Roberts (2006), and Briner and Denyer (2012) as this reduces bias, increases objectivity, and identifies gaps in the literature. We intend to provide critical insights through a theoretical synthesis to uncover how institutional distances affect a firm's decision regarding the equity-based entry mode into international markets. This being so, our review includes the extant literature on entry mode choice, i.e., the level of resources’ commitment in international markets (Ahsan and Musteen 2011), and the the choice between Greenfield and Merger and Acquisitions (M&A).

To select the relevant articles for this systematic review, we used Scopus and Web of Science (WoS) since these databases contain the highest number of indexed publications. Although Anderson and Gatignon published their seminal manuscript on the choice of entry mode into foreign markets in 1986, our search found studies that addressed the influence of institutions (economic and sociological perspectives) on the entry mode of MNCs into foreign markets, beginning with the article of Yiu and Makino (2002). It is worth mentioning that the institutional distance construct was introduced by Kostova (1999) in her study on the transfer of strategic management practices from parent companies to their international subsidiaries. However, this construct was only used to explain the entry mode choices in foreign markets in Yiu and Makino’s (2002) study. For this reason, our search for articles on institutional distances and entry modes begins in 2002 and runs until June 2022.

2.1 Search strategy

Our search strategy focused on two stages. First, we focused on identifying seminal articles on entry modes into the international market that used institutional theory as support. We searched on Google Scholar using the words: institution* AND “entry mode” and found Meyer (2001), Brouthers (2002), and Lu (2002), with 1141, 1562 and 641 citations, respectively. We added the article of Kostova and Roth (2002) with 2991 citations, as it is acknowledged as a seminal article in institutions and IB fields. Second, based on the keywords used by the authors of those seminal articles, we broadened our search to the WoS and Scopus databases. In the WoS, we selected the main collection: Science Citation Index Expanded in the business, management and economics categories, and limited the search to peer review articles. We used the keywords “Entry mode”, “Foreign entry mode”, “Establishment mode”, Institution*, “Institutional distance”, “Ownership strategy”, Acquisition, “Cross-border acquisition”, “Cross border acquisition”, Greenfield, “Greenfield investments”, WOS, “Wholly-owned subsidiary*”, Wholly owned subsidiary*” “Joint venture”, “International joint venture”, Cross-border M&A*”, “Cross-border mergers and acquisitions”, and the Boolean operators AND, OR. It is worth mentioning that the keyword “establishment mode” was included in the search because some authors consider the choice of greenfield or acquisition independent of the choice of entry mode (WOS or JV, or full or partial ownership) (Brouthers and Hennart 2007). We used the same set of keywords to search the Scopus database, restricting business, management and accounting and economics, econometrics and finance areas. We did not restrict the search to specific journals, but established 1999 as the beginning of the search since that is when the institutional distance construct first appeared in International Business (IB) studies. The search in both databases resulted in a set of 279 articles.

2.2 Article selection

The studies we selected had to address entry modes into international markets based on institutional theory and, specifically, institutional distances as antecedents of the entry mode. On comparing articles from both databases (Scopus and WoS), we removed 133 duplicate articles. The remaining articles (146) then formed the initial base for analysis (Fig. 1). Following this, we exported the abstracts to a spreadsheet and proceeded with the first step of the article selection. We examined each title and read the abstracts to determine whether they adhered to the study's aim. This analysis resulted in the removal of 55 articles whose dependent variable was neither “entry mode” nor ownership or establishment mode. We evaluated the remaining 91 articles (see Appendix 1) from the perspective of quality, downloaded them, and followed a specially designed analysis framework.

The analysis showed that of the 91 studies, 49% had been published in the six years from 2017 to 2022, and 77% in the ten years from 2013 to 2022 (Fig. 2). These figures revealed that the influence of institutional distance on entry mode is a relatively new theme and has attracted growing interest in recent years. The selected articles were published in 41 journals, with the Top 10 representing 57% of these studies (Fig. 3). Further analysis reveals that 51 articles (56%) are ranked ABS 3 and above.

2.3 Data analysis

To collect the basic information in each article, we used a template as a guide for the analytical reading, coding, and article retrieval (Table 1). We organized and uploaded the relevant articles to Mendeley Reference Manager software. We double-checked the uploaded articles to be sure that Mendeley had properly collected the data and input them correctly for citation and references purposes. Then, we generated a file and exported it to NVivo 12, a content analysis software, and proceeded with the analytical steps (Fig. 4).

We marked and included a code for a set of words, sentences, or paragraphs during the analytical review. At the end of the analysis and codification of the articles, we extracted reports that made it possible to organize and synthesize the content of each code and to identify and compile the objectives, methodology and variables used, as well as the commonalities and disparities in the results of the empirical tests and findings. The outcomes of these studies reveal the direct and moderating influence that institutional distances have on the entry mode choice, and reveal the findings obtained from the empirical tests of those selected articles.

3 Entry modes

Entry mode choice into a foreign market is extensively analyzed in the literature (Brouthers and Hennart 2007; Morschett et al. 2010). Studies assume that the entry mode choice allows firms' strategies to improve competitiveness, efficiency, and critical resources control. What is more, it is acknowledged in the literature that the choice of entry mode and its implementation determines both the success and failure of strategies (Anderson and Gatignon 1986; Brouthers 2002, 2013; Ragland et al. 2015).

While several theoretical streams and their ramifications have been used to explain entry mode choice into foreign markets, literature reviews have pointed out Transaction Cost Theory, Eclectic Paradigm, and Institutional Theory as the most common (Canabal and White 2008; Datta et al. 2002; De Villa et al. 2015; Laufs and Schwens 2014; Schellenberg et al. 2018; Surdu and Mellahi 2016). Some authors add the Uppsala Model to this list (Canabal and White 2008; Datta et al. 2002; De Villa et al. 2015; Schellenberg et al. 2018; Surdu and Mellahi 2016), along with the Real Options model (Datta et al. 2002; De Villa et al. 2015) and the RBV (Canabal and White 2008; Datta et al. 2002; Schellenberg et al. 2018;). These theories offer different premises regarding the relative importance of the factors that influence entry mode choice.

When they decide to invest in new markets, MNCs determine the degree of ownership of their operations overseas (Lee et al. 2014). The IB literature categorizes entry modes as non-equity-based (i.e., no direct investments abroad, such as exports and contractual agreements) and equity-based (i.e., when there is a direct investment through a greenfield project or an acquisition) (De Villa et al. 2015; Kumar and Subramaniam 1997; Pan and Tse 2000). In the equity-based entry mode, MNCs may set up wholly-owned subsidiaries (WOS) or share ownership with partners by forming joint ventures with majority, equal or minority control (Lee et al. 2014).

An MNC will most likely take a lower share in a culturally distant country in order to learn the local culture from its partner and use the partner’s social network to minimize possible cultural rifts (Yiu and Makino 2002). On the other hand, when home and host countries have a common political history or even the same language, religion or legal system, MNCs believe that it is easier to adapt to the local environment and thus commit more resources for investment in the host country (Guler and Guillen 2010). Perceived uncertainty can be reduced, albeit partially, when countries are similar in one or more of the dimensions mentioned earlier (political background, language, religion or legal system) (Lee et al. 2014).

Institutional variables influence entry mode and the level of resources that the MNC will commit to the host country. In addition, aspects of the host country’s legal system are essential considerations when forming an international alliance and selecting a partner for an international joint venture (Roy and Oliver 2009) This is particularly so since a perception that the host country's legal rules may be flawed and affect the repatriation of income and/or increase coordination costs is a factor that might hinder intentions to form an international alliance (Roy and Oliver 2009).

4 Institutional distances

4.1 Databases and proxies to measure institutional distances

The availability of secondary data has facilitated research and empirical testing of the relationship between entry modes and institutional distances. Several international institutions provide statistical data (OECD, World Bank, IMF, to name a few) at the country level, which make it possible to conduct rich cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses. While the proliferation of these databases and statistical indices facilitate research, it does not allow uniform measurements in studies that employ the institutional distance construct and it inhibits the advancement of IB theory. Our review shows 36 different data bases used as sources to measure the quality of institutions and institutional distances in the different distance dimensions used in the IB literature (formal and informal, regulative, normative and cultural-cognitive, cross national distances (Berry et al. 2010) and psychic distance. It is likely that the search for new concepts, frameworks, and indicators that help explain firms' decisions when entering international markets is an attempt to develop robust measures of the institutions, which is one of the main challenges of institutional theory (Peng et al. 2009).

Table 2 includes the most used variables, sources, and proxies in institutional distance studies and entry modes in foreign markets. The two most widely used databases for measuring formal (and regulatory) institutional distances are the World Bank's—World Governance Indicators (WGI) and the Index of Economic Freedom (IEF) published by The Heritage Foundation. The IEF is used to measure the level of institutional development or the strength of the institutions that support the market, while the WGI is used to measure the level of governance in countries, more specifically, the extent of the institutions' influence on economic activity.

With regard to informal (and normative) institutional distances, the most used databases are the Hofstede (1980) cultural dimensions and the Global Competitiveness Report (GCR) of the World Economic Forum. The Hofstede’s cultural dimensions (1980, 2001) is the indicator most used to measure the cultural distance between countries. It encompasses four dimensions: power distance, individualism, masculinity, and uncertainty avoidance. Later, two more dimensions were incorporated: long/short term orientation (Hofstede 2001), and indulgence/restraint (Hofstede et al. 2010). The GCR collects data in a series of indices that cover the political, economic, financial and social environment, grouped into twelve pillars: Institutions, Infrastructure, ICT adoption, Macroeconomic stability, Health, Skills, Product Market, Labor Market, Financial system, Market size, Business dynamism, and Innovation capability. Due to the broad scope of these indices, scholars also use this database to measure formal institutional distances (e.g., Lee et al. 2014; Ilhan-Nas et al. 2018a; Rienda et al. 2021; Ilhan-Nas et al. 2018b; Arslan and Larimo 2010; Chen et al. 2017; Williams et al. 2017; Powell and Lim 2017, 2018; Yiu and Makino 2002; Sartor and Beamish 2018; Ando 2012).

The Hofstede four and six dimensions of culture were also utilized to measure cultural and cognitive distances in 46 of the 91 articles collected for this literature review. The World Development Indicator (WDI) developed by the World Bank is the most popular database used in studies that adopt the disaggregation of the distance construct proposed by Berry et al. (2010). Researchers use the indicators to measure the economic, financial, political, demographic, and knowledge distances. To measure geographic distances, scholars prefer the Geobytes dabase and CIA Factbook. Both databases provide the distance between cities which is calculated applying the “Great circle distance” method using the city’s longitude and latitude. The two other most utilized variables for those scholars that prefer the cross national distances approach proposed by Berry et al. (2010) are administrative distance and Knowledge distance. The former measures the colonizer-colonized link, the common language and countries' legal system, and data are collected from the CIA Factbook database and La Porta et al. (1998). The latter (Knowledge distance) uses data from the United States Patents and Trade Office (USPTO), World Development Indicators (WDI) and Information Sciences Institute (ISI) related to the number of patents and scientific articles as a proxy for each country’s level of knowledge. To measure psychic distance, the most used Dow and Karunaratna (2006) dimensions are language, and religion.

4.2 Overview of the literature

The literature shows that internationalization decisions are influenced by uncertainty in relation to the target market (external uncertainty), but also by the distance between the MNC's country of origin and the destination country (internal uncertainty) (Anderson and Gatignon 1986). Thus, the concept of distance has become an important variable in studies involving entry into foreign markets. However, distance has been conceptualized in various ways. Beckerman (1956) proposed the concept of psychic distance to explain how managers' perception of differences between home and host affected the internationalization of Swedish companies. Kogut and Singh (1988) created a cultural distance index that incorporated Hofstede's dimensions of culture (1980, 2001). Later on, this construct (cultural distance) was developed to incorporate measures from (Schwartz 1994). Afterwards, the study by House et al. (2004) (i.e. Globe study) extended the concept of cultural distance and proposed new indicators for this construct. In the empirical literature, cultural distance is the indicator most frequently used to gauge the differences between home and host countries, the level of influence on the entry mode, and the ownership of MNC in foreign markets (Dow and Larimo 2009). Other researchers expand the concept of distance to include additional dimensions. Ghemawat (2001) proposed four dimensions of distance (administrative, cultural, economic, and geographic), and Berry et al. (2010) proposed nine dimensions (administrative, cultural, demographic, economic, financial, geographic, politics, knowledge and global connectivity). Kostova (1999) introduced the concept of institutional distance as a way to broadly capture differences between countries, including cultural distances and also regulatory and normative distances.

Differences between home and host institutional environments (institutional distances) impact MNC strategies (Estrin et al. 2009; Gaur and Lu 2007; Xu et al. 2004; Xu and Shenkar 2002). Institutional distance has been classified into regulatory, normative and cognitive (cultural-cognitive) dimensions based on the categorization attributed by Scott (2014) (e.g., Arslan and Larimo 2010; Gaur and Lu 2007; Xu et al. 2004; Xu and Shenkar 2002). However, more recently Estrin et al. (2009) used the classification of institutions proposed by North (1990)—formal and informal—to study the effects of institutional distances on the MNC choice of entry mode. Some authors prefer to use North's (1990) classification of institutions because they consider the separation between the formal and informal dimensions to be clearer, thus avoiding the overlap between the normative and cognitive pillars of (Scott 2014; Arslan and Larimo 2011).

The central idea of institutional distance research is that companies doing business in foreign markets are exposed to institutional environments in the markets where they operate that are different from those of their own country, consequently they face uncertainties and risks (Kostova 1999). The extent of these differences (institutional distances) determines the challenges faced in each of the environments and influences the firm's management decisions and actions (Kostova et al. 2020). However, it is not only the differences between country contexts that matter, but also the direction of those differences.

Institutional distance was considered in many studies as the absolute value of the difference between institutions in two countries. This suggested that the distance was symmetric regardless of variation in the context of countries. The use of this approach implies considering the distance between two emerging countries or two developed countries to be similar. However, it is known that the differences between the contexts of one and the other can be comparatively very different (Chikhouni et al. 2017).

To solve the issue of symmetry and the disagreement raised by Shenkar (2001) regarding the use of the institutional distance construct, subsequent studies began to adopt the direction of distance. In this way, distance is “positive” when the MNC goes to a country that is more institutionally developed than its country of origin. On the other hand, distance is “negative” when institutions in the MNC's home country are more developed than those in the target country.

MNC generally enter countries with less developed institutions in relation to their country of origin (negative institutional distance), seeking benefits such as low labor costs, availability of natural resources or growing markets (Dunning 1998). Although negative distance is valuable for an MNC to exploit its specific advantages such as technology and managerial capacity (Konara and Shirodkar 2017), the risk and uncertainty associated with managing activities in a less institutionally developed country may outweigh the benefits. The reason is that this environment compared to that of the country of origin has laws and regulations that are less stable, sometimes ambiguous, and difficult to comply with, which can pose problems regarding technology transfer and the security of property rights, thus inhibiting investments (Hernandez et al. 2018). Additionally, with reliable information not being available, costs to acquire knowledge about the local market, and how to deal with information asymmetry are increased (Konara and Shirodkar 2017, 2018; Trapczynski et al. 2020). Uncertainty in this type of institutional environment poses additional challenges to the MNC and negatively influences its ability to comply with local requirements and gain legitimacy (Chan and Makino 2007).

Institutions can also promote and facilitate a firm’s entry and adaptation to the local market, and the benefits of distance may outweigh the costs in some situations. Firms internationalize to countries with high-quality institutions for different reasons, such as escaping from limitations in their home market, seeking strategic assets and new technologies, or to gain reputation and publicize their brand (Luo and Tung 2007). Uncertainty arising from lack of familiarity with local institutions is reduced when the institutional environment of the target country is more transparent, has laws that protect intellectual property, a justice that respects contracts and a market that supports efficient transactions (Hernandez and Nieto 2015). In these cases, the large institutional distance (positive distance) acts by encouraging greater commitment of resources, since the costs of conforming to the local environment are reduced and obtaining legitimacy is easier (Cuervo-Cazurra and Genc 2011).

5 Main findings

The framework we set out in Fig. 5 shows what typologies this review will address and how they are organized.

The inner circle shows from which construct the concepts and theoretical perspectives used to support the phenomenon of distance derives. The brown circle shows the strategic choices of an MNC when entering foreign markets. The blue circle shows the entry mode and level of ownership the MNC holds in its subsidiary abroad. The orange circle refers to the MNC's target markets in terms of their economic development. The green circle shows the various levels of analysis of the distance phenomenon.

5.1 An overview of the studies

The articles collected for this review show outward investment studies, with 36 referring to investments of emerging multinationals (EMNC) abroad, 24 of developed multinationals (DMNC), and 31 studies encompassing multiple countries (Table 3). These investments target multiple countries (59 studies—65%), emerging and transition countries (28 studies—31%), and only 4 whose target is developed countries (4%).

The analysis of the outward investments of emerging countries, shows that three countries stand out with a total of 19 studies—China (9), India (5), and Taiwan (5)—out of an overall total of 36 studies. Compared to other emerging and transition countries, these three countries have deserved greater attention from researchers in recent years. This is due on the one hand to the growing volume of investments abroad and, on the other hand, to cultural and political differences.

5.2 Acquisitions and greenfield

EMNCs prefer acquisition when the host country is perceived as more institutionally developed than the home country (Mueller et al. 2017), has high-quality formal institutions (Rienda et al. 2021), and when the cultural distance between home and host is small (Rienda et al. 2019). However, poorly developed institutions also motivate EMNCs to acquire in foreign markets. Brazilian EMNCs, for instance, prefer acquisitions in markets with high rates of political uncertainty (Chueke and Borini 2014), while domestic economic uncertainty is the main determinant of acquisition choices made by Chinese EMNCs (Sun et al. 2021). Additionally, Indian multinationals with experience in cross border acquisitions also choose acquisition as an entry mode into culturally distant and politically risky countries. International experience in acquisitions moderates the negative effects of cultural distance and the political institutions of the host (Rienda et al. 2018).

EMNCs choose greenfield as a way of entering culturally distant countries (Chueke and Borini 2014), with a poorly developed institutional environment (Mueller et al. 2017);. and when the firm lacks experience in cross border acquisitions (Rienda et al. 2018) Greenfield entry mode increases the synergy between the parent company and the subsidiary's operations abroad (Harzing 2002), reducing internal uncertainty concerning the transfer of managerial practices. Additionally, an EMNC chooses greenfield to avoid legal obstacles, mitigate institutional pressures, and ensure legitimacy (Sun et al. 2021; Meyer et al 2014).

Greenfield projects mean many challenges for MNCs entering transition economies. When the distance between the formal institutions of the target market and the home country is high, MNCs need to adapt to the requirements and rules of the local market and run the risk of being discriminated against by the local government (Dikova 2012). On the other hand, in targets with a similar institutional environment (or low institutional distance between home and host) an MNC will choose an acquisition entry which lowers the costs for integration and provides access to the strategic assets of acquired local brands and marketing intelligence (Dikova 2012). Acquisition can also be a choice over large regulatory and normative distances when an MNC enters an emerging market (Van Dut et al. 2018).

When taking into consideration informal institutions, we find contradictory results. For some, high informal institutional distances result in greenfield projects (Arslan and Larimo 2011; Chueke and Borini 2014). Greenfield investments allow the subsidiary to integrate into the corporate structure of the parent firm and can also incorporate a certain level of flexibility that facilitates adjusting to local requirements and demands (Slangen and Hennart 2008). The organization can adjust to local demands with local employees who understand the host country's norms, values, and routines (Xu et al. 2004).

However, not all researchers share the notion that a greenfield project can be justified when the informal institutional distances between home and host country are high. Van Dut et al. (2018) argued that when comparing greenfield with acquired subsidiaries, the latter finds it easier to communicate with the locals and has a more significant opportunity to obtain knowledge from the local organization, which benefits the MNC. The greenfield subsidiary has less knowledge of the local culture, implying communication problems with its peers which, in turn, hinders efforts to gain legitimacy (Meyer 2001).

Informal institutional distance, represented by the cultural distance between home and host country, causes internal uncertainty concerning the management of the post-acquisition process. Flaws in the subsidiary's process of integrating with the managerial practices of the parent company can lead to increased transaction costs and reduced operational efficiency (Chueke and Borini 2014). To avoid these additional costs, which can eat up the resources initially earmarked for international expansion, an MNC tends to opt for greenfield projects and thereby increase the synergy between the operations of the parent company and the subsidiary (Chueke and Borini 2014).

5.3 Full versus partial acquisitions

Institutional distances influence entry mode choice and the level of resources committed in foreign countries. An MNC is more likely to make full acquisitions in emerging markets when the institutional distances between home and host countries are large (Contractor et al. 2014). The level of uncertainty perceived by the MNC, due to the long-distance, plays a helpful role in its decision to fully acquire a firm in this market with regard to the best way to protect its investment. Full acquisition is true for a US acquirer, but not for a Japanese acquirer who is more willing to share control and take advantage of the synergy of local partners and former owners (Contractor et al. 2014).

Other factors that may signal a lower risk, give the MNC greater confidence to invest in foreign markets. The cultural similarity between home and host countries (Dang et al. 2018) or both parties’ proficiency in a common language decreases uncertainty and increases the likelihood that the MNC will opt for a total acquisition (Cuypers et al. 2015). In addition to cultural aspects, the host country's formal institutional context also contributes to a greater proclivity for total acquisitions. The quality of the institutions that involve the economic opening of the host market (e.g., absence of restrictions on FDI), and policies that preserve freedom of trade, are other factors that reduce uncertainty and predispose the MNC to a more significant commitment of resources (Dang et al. 2018).

Previous studies show that the determinants of entry strategy differ between the service and manufacturing sectors (Brouthers and Brouthers 2003), with EMNCs preferring full ownership in acquisitions involving soft servicesFootnote 1 (Lahiri et al. 2014; Quer and Andreu 2021). However, Chinese state-owned MNCs display idiosyncratic behavior, sharing ownership with a local partner over large institutional distances in international acquisitions in the tourism sector (soft services) (Quer and Andreu 2021). DMNCs also prefer partial acquisition (Lahiri et al. 2014) in the soft services sector when institutional distance is higher. In contrast, DMNCs prefer full ownership when the cultural distance is large (Morschett et al. 2008).

However, both EMNCs and DMNCs are more likely to opt for partial acquisitions in hard services.Footnote 2 Full acquisition is preferred in the hard services sector when the institutional distance between home and host is large (Lahiri et al. 2014).

Full acquisitions are preferred in emerging markets with economic growth and low foreign acquisition restrictions (Arslan and Dikova 2015). A Firm’s characteristics mitigate the negative effects of institutional distance between home and host. Previous experience in the emerging market target predisposes DMNCs to full acquisition despite the large difference between formal and informal home and host institutions (Arslan and Dikova 2015).

EMNCs acquire less equity than DMNCs primarily in high-tech industries. (De Beule et al. 2014). To protect their knowledge and technology, the strategy of both may change to full ownership when there is uncertainty regarding the protection of intellectual property in the target country. Additionally, a greater institutional distance between home and host with regard to trade and investment freedom increases the probability of full acquisition for the EMNC, but not for the DMNC in developed countries (De Beule et al. 2014).

Large institutional distance is generally associated with partial acquisition in emerging market investments (Lahiri et al. 2014; Arslan and Dikova 2015; Xu et al. 2004; Demirbag et al. 2007). This is true for DMNCs, but not for EMNCs who prefer greater ownership than DMNCs. EMNCs are more risk-prone and opt for an entry mode with greater ownership, despite uncertainty (Malhotra et al. 2016; Lahiri et al. 2014). EMNCs' ability to manage relational risk is greater than DMNCs when entering emerging markets. Thus, an EMNC is more likely to accept partners. However, when cultural distance increases, both EMNCs and DMNCs reduce their preference for partnerships (Valdés-Llaneza et al. 2021). Likewise, cultural distance (high Uncertainty Avoidance Distance) increases the probability of partial acquisition (Contractor et al. 2014).

Using a sample of US MNC acquisitions, Malhotra (2012) showed the existence of a curvilinear relationship between cultural distance and the level of ownership of affiliates abroad. Partial ownership is more likely over large cultural distances and small geographic distances, and/or small cultural distances and large geographic distances. Additionally, tests revealed that total ownership is more likely when cultural distance and geographic distance are simultaneously low or high. (Malhotra 2012).

The relationship between full ownership and large cultural and geographic distances was also observed by Contractor et al. (2014). US acquirers have a high probability of full ownership in acquisitions in China and India due to the large institutional distance between the US and those countries. However, Japanese acquirers, being not so far away from China and India, are more likely to opt for minority acquisitions than US acquirers are (Contractor et al. 2014).

However, the greater the formal institutional development of the target country that has intellectual property protection, the lower the level of uncertainty. Institutional security increases the likelihood that an EMNC will opt for partial acquisition in cross-border acquisitions (Ahammad et al. 2018). On the other hand, the low institutional quality of the host country can be mitigated by geographic and linguistic proximity. In this scenario, acquirers perceive greater ease of adaptation and lower coordination and control costs, and are willing to opt for partial acquisition, choosing to share the property with a local partner (Gaur et al. 2022).

Scholars criticize the use of objective measures to assess the institutional environment since this has so far led to all firms perceiving the environment in the same way. Each firm is characterized by different capabilities and scope of activities, which influences its perception of the institutional environment of home and host (Trąpczyński et al. 2020; Lo et al 2016). Trąpczyński et al. (2020) show that in countries with high-quality formal institutions, the perception an EMNC has of the negative effects of distance is reduced. The quality of formal institutions has a positive effect on the probability of a firm choosing full ownership. On the other hand, in distant countries with low institutional quality, the EMNC may adopt a conservative position on risk aversion and prefer to maintain a low level of ownership in its subsidiary.

5.4 Full, higher and lower level of ownership

The same positive relationship between institutional distance and ownership is observed in the manufacturing sector. Cultural distance increases the likelihood of majority ownership in DMNC subsidiaries of the manufacturing industry (Powell and Lim 2018). Manufacturing DMNCs also retain majority ownership in subsidiaries located in developing and transition countries, even as political instability in these countries increases (Williams et al. 2017). Contrastingly, non-manufacturing subsidiaries hold a minority stake (Powell and Lim 2018).

At the same time, with regard to investment risks, institutional differences between home and host increase the uncertainty level of decision-makers. According to TCE, firms are likely to internalize their activities to minimize high transaction costs in uncertain and risky environments (Brouthers 2002). Large formal institutional distances drive DMNCs to assume a greater equity position in targets located in emerging and developing economies (Ellis et al. 2018; Kedia and Bilgili 2015). Additionally, the quality of governance in the target country positively influences ownership (Lahiri 2017). This is also true for EMNCs seeking to acquire a high level of ownership when the target is located in countries with more developed formal institutions (Yang 2015; Liou et al. 2017a, b). On the contrary, in regulatory and administratively distant countries, EMNCs tend to acquire less ownership (Lee et al. 2014).

However, the level of internal uncertainty distinctly affects DMNCs and EMNCs. The perception of distance between home and host and the direction of that distance leads EMNCs and DMNCs to different decisions. Psychic distance (Håkanson and Ambos 2010) negatively affects ownership, but distance direction (positive or negative), which indicates whether the host is more developed than the home (positive direction), or the reverse (negative direction), moderates this effect. Thus, the EMNC that enters a developed market increases the volume of ownership as the psychic distance increases, while the DMNC decreases its share of equity in a target located in an institutionally developed country when the psychic distance increases (Chikhouni et al. 2017). On the other hand, EMNCs are likely to increase their equity stakes when they acquire firms in the same industry. The related industry reduces valuation costs and adverse selection risks (Yang 2015).

EMNCs perceive the need for control when operating in geographically and culturally distant countries and opt for a high level of ownership (Lee et al. 2014). One of the explanations is that some EMNCs focus on acquiring the resources they need to place themselves at the same level as developed countries and to maintain their competitiveness in the global market (Luo and Tung 2007). In this strategy, EMNCs do not consider the risks associated with cultural and geographic distances that determine the choice of entry mode (Lee et al. 2014). In contrast, DMNCs adopt a low equity share when investing in culturally distant emerging countries (Ellis et al. 2018).

Historical ties between home and host (post-soviet economies) predispose acquirers to acquire a high percentage of shares regardless of large formal institutional distances. However, when these institutional distances increase, acquirers with historical ties tend to reduce ownership in the target but maintain a high percentage of shares. In contrast, acquirers with no historical ties increase their participation in the target as the formal institutional distances increase (Kedia and Bilgili 2015).

5.5 Wholly-owned subsidiaries (WOS) and Joint ventures (JVs)

Firms in countries with high institutional quality perceive a great distance when they target countries with low institutional quality. In countries with a lower level of institutional quality, the presence of institutional inefficiencies encourages shared ownership with a local partner who will facilitate overcoming these deficiencies (Del Bosco and Bettinelli 2020; Slangen and van Tulder 2009; Pehrsson 2015; Askarzadeh et al. 2021). Strong regulatory and normative constraints (Yiu and Makino 2002; Ando 2012), as well as political risk and the cultural distance between home and host (López-Duarte and Vidal-Suárez 2010), predispose the MNC to choose JV or lesser ownership over WOS.

However, in regulatory and administratively distant countries, EMNCs tend to choose a JV (Kittilaksanawong 2017). Large informal institutional distances (Yang et al. 2022) and regulations (Kittilaksanawong 2017; Ávila et al. 2015) also predispose an EMNC to choose a JV as an entry mode. The adoption of a JV or a lower stake in the target's capital is not widespread in such circumstances. In some countries with large institutional distances, EMNCs maintain a high level of equity. These firms benefit from learning from their local partner and simultaneously have control over operations, which allows strategic alignment with the parent. (Kittilaksanawong 2009, 2017).

However, there is no unanimity on the theoretical argument that informal institutional distances impel an MNC to seek a local partner to mitigate uncertainty and help the MNC to better interact with the institutional environment and stakeholders. Ávila et al. (2015) segregated informal institutions into values, beliefs and relationships, and while an increase in distances between an EMNC and the target regarding values and relationships pointed to shared ownership, an increase in beliefs indicated total ownership (WOS). The study by Arslan and Larimo (2010) on the entry of DMNCs in countries undergoing a political and economic transition also pointed to the choice of WOS over large normative distances. This result contrasts with previous studies (e.g., Kaynak et al. 2007; Yiu and Makino 2002; Xu et al. 2004), and the difference may be related to the sample, since the latter two studies address Japanese MNC investments, and the study by Kaynak et al. (2007) revealed that a joint venture was chosen when normative distances were large, but with only one host country in their sample. A possible explanation for the result presented by Ávila et al. (2015) is that different beliefs between an EMNC and the host can make it difficult to identify and select an appropriate partner in the target, and that because of this, WOS is chosen.

DMNCs prefer to choose WOS when expanding into emerging and transition economies (Yiu and Makino 2002; Xu et al. 2004; Kaynak et al. 2007; Meyer et al. 2009; Choromides 2018; Kaynak et al. 2007). While DMNCs typically invest in international markets to exploit their competitive advantages (Child and Rodrigues 2005), in distant markets they choose lower ownership to access local knowledge and dilute governance costs.

An EMNC internationalizes for different reasons and faces more challenges than a DMNC does. The entry of an EMNC into developed countries suggests that the EMNC seeks knowledge and resources to gain competitiveness and expand globally (Chikhouni et al. 2017; Luo and Tung 2007). The EMNC seeks to acquire strategic assets through the internationalization process, which favors the use of WOS (Demirbag et al. 2009; Yang et al. 2022). In this way, greater equity allows the EMNC to have control over the target's tangible and intangible assets, facilitating the transfer of knowledge (Gaffney et al. 2016).

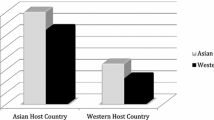

DMNCs and EMNCs choose different equity levels in emerging markets. A DMNC acquires high levels of equity in acquisitions in developed countries and commits to a lower volume of resources in emerging markets. However, EMNCs acquire higher levels of ownership than DMNCs when they make acquisitions in emerging markets. The reason is that an EMNC is used to operating in underdeveloped market institutions in its home country (Cuervo-Cazurra and Genc 2008), and thus, compared to a DMNC, an EMNC perceives less uncertainty when investing in other emerging markets. DMNCs prefer to set up a JV and share the equity with a local partner in emerging countries (Arslan and Larimo 2017; Adamoglou and Kyrkilis 2018; Duanmu 2011), and will more readily abandon the investment if expectations are not met. Additionally, shared investment with local partners facilitates the introduction of the DMNC into the emerging country's informal business network (Domínguez et al. 2021).

External uncertainty impacts DMNCs and EMNCs similarly. In countries with a quality regulatory environment, both EMNCs (Ávila et al. 2015) and DMNCs are more likely to choose WOS (Slangen and van Tulder 2009), or a higher ownership position as an entry mode (Morschett et al. 2010; Xu et al. 2004; Liou et al. 2017b). However, when there is a large normative and cognitive distance between home and host, both DMNCs and EMNCs adopt a low level of ownership. The negative influence of institutional distance on ownership is stronger for a DMNC than for an EMNC (Liou et al. 2017b).

Research on EMNC entry mode shows that the government can play a fundamental role in the internationalization decision, specifically in the way these firms enter international markets. The idiosyncratic characteristics of these EMNCs give rise to different decisions. Ávila et al. (2015) in their study on the internationalization of Brazilian multinationals found a strong and significant relationship between state support and the choice of JV. The choice of JV is also observed in Chinese State-owned MNCs that are subject to great institutional pressure (Chung et al. 2016). These results are in line with a similar study conducted by Pinto et al. (2017) on government support for the internationalization of Brazilian firms. In that study, the authors justify the government’s offer of guarantees that minimize the risk of investing over large distances and predispose a Brazilian firm to choose WOS as an entry mode. Chinese MNCs with high R&D intensity are also more likely to choose WOS than JV (Chung et al. 2016).

For other EMNCs, however, the probability of opting for WOS may decrease when there are large cultural and institutional distances between home and host countries (Lo et al. 2016; Li et al. 2017). The negative effect of cultural distances on ownership can be mitigated by good host country governance and the EMNC will prefer to work with local partners and reap the benefits of collaboration (Chang et al. 2012). Additionally, if the entry strategy is to follow the customer, this relationship can make the EMNC ignore the cultural distance and form a WOS in the country where its customer base is located (Lo et al. 2016). Essential market information is provided by these customers, reducing uncertainty.

Large cultural distances increase the likelihood of the MNC choosing a JV in emerging markets (Demirbag et al. 2007) Other institutional features like political restrictions, linguistic distance and a high perception of corruption lead investors to opt for setting up a JV with local partners (Demirbag et al. 2007, 2010).

The large distance between the level of corruption at home and the host increases the probability that foreign investors (DMNC) will choose WOS over JV. The probability of choosing WOS decreases if investors are market-oriented and come from countries with a lower level of corruption than the target country. In contrast, the level of corruption in the target does not affect the decision on the entry mode of the investor coming from countries with a similar or higher level of corruption (Duanmu 2011).

Large institutional differences between home and host (differences in religion, education, industrial development, and democracy) increase the likelihood that a DMNC will establish JVs (Dow and Larimo 2009). The lack of a language barrier favoring the choice of JV (López-Duarte and Vidal-Suárez 2010) and previous experience in managing international JVs both increase the probability of choosing a JV in a new target (Slangen and van Tulder 2009), or a subsequent entry (Yiu and Makino 2002). This is because ease of communication and previous experience in structuring a JV reduces uncertainty and the costs of coordination and control, facilitating cooperation with a local partner.

Family DMNCs prefer wholly owned subsidiaries (WOS) in countries with a higher level of institutional quality compared to home (Del Bosco and Bettinelli 2020). Full control of subsidiaries in foreign markets with large cultural distances is also pursued by Italian family SMEs. These firms perceive greater risks and difficulties in managing local partners than the risks and uncertainties associated with operating with full control in these countries. In culturally distant countries, the difficulties associated with the liability of foreigners appear to be less relevant. Total control is preferred in order to avoid the risk of conflicts and misunderstandings with culturally distant partners, and to preserve family values (Del Bosco and Bettinelli 2020).

The family EMNC will opt for a smaller share of equity in its affiliates when the institutional distance is small and there are a greater number of independent directors. On the other hand, the share of equity owned by family-owned board members is positively related to the amount of equity held by the MNC in its affiliates at large institutional distances. This relationship favors majority ownership if the host is a developed country (Ilhan-Nas et al. 2018a). Additionally, host countries with high governance quality lead EMNC’s with a high degree of family control to prefer WOS (Chang et al. 2014). The preservation of family assets may explain the need to exercise full control over foreign operations.

6 Main findings: summary

This literature review reveals some inconsistencies. There is no consensus on the relationship between institutional distance and the entry mode choice (Dikova and Brouthers 2016). Some studies point to an entry mode with low resource commitment and a low level of control when the institutional distance is large (Arslan and Larimo 2017; Xu et al. 2004; Ando 2012). Empirical results presented by other studies reveal that when institutional distance is large, an MNC chooses an entry mode with a high level of control (Batsakis and Singh 2019; Lo et al. 2016; Askarzadeh et al. 2021; Trąpczyński et al. 2020). The context of the studies analyzed shows that the direction of distance has great explanatory power (Hernandez and Nieto 2015), the entry mode of EMNC and MNC differ, and the industry and strategic motive can influence the type of ownership (Zhang et al. 2023) (Table 4). The influence of some of these boundary conditions on ownership (or the level of resource commitment) can be seen below (Table 4).

Scholars have proposed different frameworks with different dimensions of distances (Berry et al. 2010; Ghemawat 2001; Kostova 1999; Kogut and Singh 1988) to better explain the effects of distance on the choice of entry mode and ownership. However, the main issue is to align the phenomenon, the supporting theory, and the indicator that will measure institutional distance. The reason for some inconsistencies observed in this study lies in this lack of alignment. Thus, measuring the formal institutional distance between home and host using the Economic Freedom Index (Pehrsson 2015; Yang and Deng 2017) may be inconsistent with North's (1990) concept of formal institutions. The World Governance Indicator (WGI) could be more appropriate (Kostova et al. 2020). Likewise, informal institutions as conceptualized by North (1990) are not entirely compatible with the concept and theoretical support given by Hofstede (2001) to cultural distances. The use of appropriate indicators to measure institutional distances is a step towards solving some inconsistencies in studies on entry mode. However, the study of this phenomenon is complex and additional research will be necessary to use the theoretical support of institutional theory to increase our knowledge of the theme. Our review detected some gaps that are discussed below. These gaps gave rise to directions for future research that we hope will bring new insights to internationalization studies, specifically equity entry mode.

6.1 Strategic motive

The collected sample brought very few studies that include the strategic motive and its relationship with the establishment mode and ownership in international markets. The strategic motive is treated as a control variable in two articles and as a moderating variable in a third article. The Rienda et al. (2018) study shows a direct relationship between the strategic motive and the probability of acquisition. However, the authors do not discuss the implications and justifications for such a result. Yang et al. (2022) argue that EMNCs need to align the ownership strategy in international acquisitions with the strategic objectives of their projects, taking control of the subsidiary to complete the integration process. Powell and Lim (2017) go a little further and analyze the moderating effect of the strategic motive on the relationship between institutional distance and ownership. The empirical tests show a propensity to acquire a higher level of ownership when the subsidiary is a manufacturing unit and the target has more advanced techniques and production processes than the MNC. What emerges from these studies is the need for control when the reason for internationalization is strategic seeking. The main argument for control is to promote knowledge absorption with easier integration. We know that there are different strategic motivations such as market seeking, resource-seeking, efficiency-seeking and asset seeking (Contractor et al. 2014; Lebedev et al. 2015; Nachum and Zaheer 2005), but we do not know how and to what extent each of these antecedents influences the MNC's decision regarding ownership (Lahiri 2017).

6.2 Individual level of analysis

Although some researchers have called attention to the role of owners and top management team and recommended bringing analyses of the entry mode phenomenon down to the level of the individual (Canabal and White 2008; Laufs and Schwens 2014), we did not detect studies that included analyses of this phenomenon at the micro level (the individual level). The existing literature on international business has analyzed the entry mode phenomenon at the macro level, trying to understand the existing causal relationships between the specific characteristics of the firm, industry and institutions and the choice of entry mode. The individual level of analysis has been discussed in recent years within the concept of microfoundations of strategy with the production of conceptual and theoretical articles (see Felin et al. 2015), but we have yet to note empirical papers that have used constructs to demonstrate how the characteristics of individuals and their interaction within the organization are associated with certain outcomes such as an acquisition or a greenfield project in a foreign market.

6.3 Perceptual versus objective measures

Another gap detected in this review concerns the use of perceptual measures in entry mode research. Although previous research has drawn attention to the relevance of perceptions, experience and cultural background in managers' decision-making, little attention has been devoted to how decision-makers perceive institutional differences across countries and how these perceptions may influence decisions about the ownership level (Trąpczyński et al. 2020). In fact, in this review we collected only three studies that address the topic (Drogendijk and Slangen 2006; Trąpczyński et al. 2020; Lo et al. 2016) and that confirm that perceptual measures make a difference. Drogendijk and Slangen (2006) empirically tested objective and perceptual measures of cultural distance and concluded that despite being highly correlated, they differ from each other to a great extent. In their study on the outward investments of Polish firms, Trąpczyński et al. (2020) concluded that there is great variation in the perception of formal and informal institutional distances in firms operating in the same institutional environment. Lo et al. (2016) argues that objective and subjective measures have merits and limitations and that the resources available to the firm and its background mean that the perception of the same phenomenon (cultural difference and industrial policy of the host) may not be the same for different firms.

6.4 Subnational level of analysis

Although the literature that emphasizes the importance of the subnational level of analysis is becoming more extensive, our literature review found only three studies that analyzed the impact of institutional variables at the subnational level on entry mode and ownership (e.g. Duanmu 2011; Liu and Yu 2018; Karhunen et al 2014). Liu and Yu (2018) posit that there is still limited knowledge about the influence of home country institutions at the subnational level. These institutions can guarantee the MNC specific resources that ease the internationalization of the firm (Pinto et al 2017). Indeed, some advantages may be accessible not only to the home country but also to the target markets. Locations at the subnational level may have unique geographic, demographic, and political characteristics that attract specific investments to that location. Governments at the subnational level (regional, district or city level) may have different priorities and different “rules of the game” when compared to the national government. Local government can create incentives to install new industries or remove obstacles in relation to foreign investments, which increases the quality of institutions and may change an MNC's entry mode strategy.

7 Future research directions

The main objective of this study is to contribute to the IB literature by presenting a systematic review of the role of institutions and their relationship with equity-based entry modes in foreign markets. Our synthesis of the main findings reveals some gaps that may provide a promising avenue for new research designs and give rise to other theoretical streams and methodological approaches. We believe that the research directions suggested below can contribute to increasing our knowledge of the conditions imposed by institutions on entry mode decision-making and the way MNCs cope in response to the environment in foreign markets.

7.1 Strategic motive for internationalization

There is a gap in the IB literature on strategic motivation in decisions to enter new markets. Previous studies have devoted attention to entry modes in foreign markets and in particular to equity participation in cross border acquisitions (Lahiri 2017). However, with a few exceptions—in this review only the study by Powell and Lim (2017) addresses the moderating effect of the Japanese MNC strategy on entry mode in the US market—we did not detect other empirical studies that have tested the relationship between the strategic motivation of the MNC and the choice of ownership. Studies do not analyze in detail how the results differ for different types of CBAs (horizontal, vertical, related and unrelated acquisition) or CBAs with different motivations (market-seeking, asset-seeking or efficiency seeking) (Lahiri 2017). Conceptually, we know that decisions in different industries and with different motivations can influence the effects that institutional distances have on entry mode (Ghemawat 2001), ownership choices, location and target firms (Pinto et al. 2017). However, there is little evidence on how institutions affect the entry mode contingent on the strategic motivation of the MNC (Donnelly and Manolova 2020). Different institutional dimensions may be more relevant than others for some strategic choices. Understanding how different corporate strategies affect the relationship between institutions and entry mode can bring new contributions to the IB literature.

7.2 Individual level of analysis

Future research should go beyond measures of institutional distance at the macro level to employ a procedural perspective and study managers' perceptions of similarity, which may influence MNC decisions (Liou et al. 2017b). Future research may use mixed analysis methodologies, incorporating, for example, data extracted from a survey designed to collect individual executives' perceptions and preferences for a particular course of action (Dow et al. 2018). Is distance really a factor that interferes with the flow of information causing misunderstandings and increasing the decision maker's level of uncertainty, as argued by Johanson and Vahlne (1977)? Or is it a subconscious bias that the manager must guard against, but which guides his decision in the absence of evidence? Better knowledge of the mechanisms that involve the perception of managers will greatly add to our understanding of the real meaning of institutional distance in the strategic decision-making of an MNC.

Analysing the outcomes of organizations at the individual level is one of the motivators discussed by researchers in the academic conversation about microfoundations of strategy (Felin et al. 2015). The central motivation of research on microfoundations has been to discover collective concepts to understand how factors at the individual level impact organizations, and how the interaction of these individual levels originates outcomes at the firm level, and how the relationships between variables at the macro level are moderated by actions and interactions at the micro level (Abell et al. 2008). Research on microfoundations in the area of international business objective is to bring the individual back to the field of analysis and understanding how their actions and interactions affect decisions related to internationalization and entry mode. Empirical studies can confirm the propositions of existing theoretical-conceptual studies and bring new insights to entry mode and ownership studies in relation to decision-making, which is one of the antecedents of internationalization that has been scarcely studied.

7.3 Perceptual versus objectives measures

Previous research has emphasized the relevance of distance perceptions in internationalization decisions (Trąpczyński et al. 2020). A recent meta-analysis showed that perceptual measures of cultural distance have a greater effect on firm outcomes than measures based on secondary data (Beugelsdijk et al. 2018a, b). Objective measures reflect the institutional reality, which is common to all firms operating in a given market (Brouthers 2013). However, there can be wide variation in the perception of formal and informal institutional distances between firms operating in the same institutional environment (Trąpczyński et al. 2020). Objective measures do not consider that each firm is characterized by different capabilities, operational scope and management, which influence the perception of the institutional environment of home and host countries (Lo et al. 2016). Thus, future research should consider the role that managerial perceptions of the institutional environment play with regard to firm outcomes in general and, specifically, in ownership decisions in cross-border investments.

7.4 Multi-theory perspective

Internationalization theories are complementary, and a model with greater explanatory power should be based on multiple theoretical perspectives (Hill et al. 1990; Tihanyi et al. 2005). In future studies, we would suggest integrating the insights of multiple theories (e.g., Brouthers 2002; Gaur and Lu 2007). Research designs that only use variables from one theoretical approach could lead to biased statistical tests with missing variables that could, in turn, produce inconclusive and insignificant results. Thus, future studies should look at the combined effect of different variables in a multi-theory approach (Canabal and White 2008; Morschett et al. 2010).

Theories related to economic geography, social psychology and political science can constitute what we call a multi-theoretical approach. Economic agglomeration and the concepts of place and space from economic geography (which can encourage or repel economic and social activity), together with institutional distance and a firm’s characteristics can influence location (Goerzen et al. 2013). So, too, can the level of uncertainty and, consequently, the level of commitment of resources (ownership). Social psychology can contribute to IB, institutional theory and entry mode by clarifying aspects related to cognition and decision-making and by determining the influence that the executive's perception of distance and uncertainty has. Political science contributes to the geopolitical factors and political characteristics of the place (country, city, region), and brings new variables that can provide greater explanatory power to the relationship between institutions and the choice of entry mode.

7.5 Subnational level of analysis

The IB literature has adopted the country level as the unit of analysis in studies on foreign market entry (Asmussen et al. 2018). The choice of the country as the only primary source of analysis is based on the premise that there are no significant variations between the prominent locations within a country. Nonetheless, international business does not occur only at the national level, but in different locations and within different geographical units (Hutzschenreuter et al. 2020). The introduction of other geographical scales does not replace the country as a primary unit of analysis in IB but complements it. An increasing number of studies call attention to the role of subnational variations concerning culture (Beugelsdijk and Mudambi 2014; Tung and Verbeke 2010), to a broader institutional context (Crouch et al. 2009), or to different practices within a country (Walker et al. 2014). Studies on subnational variations have applied to non-Western and emerging economy settings (Witt and Redding 2014). Thus, there is a growing understanding that subnational factors such as outsourcing or insourcing R&D (Santangelo et al. 2016) are essential in IB processes (Ma et al. 2013). Additionally, Chan et al. (2010) analyzing the operation of MNC subsidiaries in the U.S. and China, confirm the importance of the subnational region as an additional unit of analysis. The variation in FDI policies within a country (subnational) may be the result of differences in the local implementation of national rules, or because the policies implemented in other subnational regions are different. Although these policies are enacted at the country level of the host country, they are often implemented at the regional level (Meyer and Nguyen 2005). In competing for a share of the inward investments, regional governments differ with regard to how they implement policies to attract such foreign resources as tax deferral, tariff reduction and concession of tax incentives (Ma and Delios 2007; Oman 2000; Zhou et al. 2002). The variation in these regional policies affects FDI flow and the cost of doing business in some regions (Meyer and Nguyen 2005).

There is broad scope for future research at the subnational level as the literature recognizes the importance of this level of analysis to increase our knowledge of the influence that the institutional environment has at regional, state and provincial levels on the entry mode and ownership of MNCs in foreign markets.

8 Conclusion, contribution and limitations

Our study answers the research question we set ourselves by informing how the existing literature conceptualizes institutional distance and what constructs and variables have been used to measure the influence on the mode of entry of MNCs in foreign markets. Thus, this study contributes to a better understanding of the institutional dimensions put forward in the literature and how they influence decision-making regarding choice of ownership. Additionally, this study expands existing knowledge about the influence that institutions have on the entry mode of MNCs from developed and developing countries (emerging and in transition). As this produces a portrait of the advances and the gaps that still exist, it suggests good avenues for investigation.

Despite its methodological rigor, this review has limitations that should be noted. Relevant articles may have been omitted from the databases used, and keywords and filters may have excluded others. Second, our study selected only peer-reviewed articles published in academic journals. As such, we did not include books, dissertations, and minutes of conference proceedings that could have also provided essential insights. Third, this review sought to provide comprehensive coverage of institutional distances and equity-based entry modes. However, a meta-analysis of the studies collected could determine the relevant institutional factors influencing entry mode choice and ownership in foreign markets. Finally, due to the restrictions imposed on the sample, the themes identified in this review are not definitive and mutually exclusive. Despite its limitations, our study nevertheless points towards excellent avenues for future research. The themes suggested above can contribute to identifying other theoretical and methodological approaches, which can bring new insights and relevant research areas.

Data availability

All data sources are dully identified in the manuscript, as well as the selection process. Data used is available on reasonable request.

Notes

References

The asterisk (*) symbol in references denotes studies included in the systematic review.

Abell P, Felin T, Foss N (2008) Building micro-foundations for the routines, capabilities and performance links. Manag Decis Econ 29:489–502

*Adamoglou X, Kyrkilis D (2018) FDI entry strategies as a function of distance—the case of an emerging market: Turkey. J Knowl Econ 9(4):1348–1373

Aguillera RV, Grogaard B (2019) The dubious role of institutions in international business: a road forward. J Int Bus Stud 50(1):20–35

*Ahammad MF, Konwar Z, Papageorgiadis N, Wang C, Inbar J (2018) R&D capabilities, intellectual property strength and choice of equity ownership in cross-border acquisitions: evidence from BRICS acquirers in E urope. R&D Management 48(2):177–194

Ahsan M, Musteen M (2011) Multinational enterprises’ entry mode strategies and uncertainty: a review and extension. Int J Manag Rev 13(4):376–392

*Ando N (2012) The ownership structure of foreign subsidiaries and the effect of institutional distance: a case study of Japanese firms. Asia Pac Bus Rev 18(2):259–274

Anderson E, Gatignon H (1986) Modes of entry: a transaction cost analysis and propositions. J Int Bus Stud 17(3):1–26

*Arslan A, Dikova D (2015) Influences of institutional distance and MNEs’ host country experience on the ownership strategy in cross-border M&As in emerging economies. J Transntl Manag 20(4):231–256

*Arslan A, Larimo J (2010) Ownership strategy of multinational enterprises and the impacts of regulative and normative institutional distance: evidence from Finnish foreign direct investments in Central and Eastern Europe. J East-West Bus 16(3):179–200

*Arslan A, Larimo J (2011) Greenfield investments or acquisitions: Impacts of institutional distance on establishment mode choice of multinational enterprises in emerging economies. J Glob Mark 24(4):345–356

*Arslan A, Larimo J (2017) Greenfield entry strategy of multinational enterprises in the emerging markets: Influences of institutional distance and international trade freedom. J East-West Bus 23(2):140–170

Arslan A, Wang Y (2015) Acquisition entry strategy of Nordic multinational enterprises in China: an analysis of key determinants. J Glob Market 28(1):32–51

Arslan A, Tarba SY, Larimo J (2015) FDI entry strategies and the impacts of economic freedom distance: evidence from Nordic FDIs in transitional periphery of CIS and SEE. Int Bus Rev 24(6):997–1008

*Askarzadeh F, Yousefi H, Bajestani MF (2021) Strong alien or weak acquaintance? The effect of perceived institutional distance and cross-national uncertainty on ownership level in foreign acquisitions. Rev Int Bus Strategy 31(2):177–195

Askarzadeh F, Lewellyn K, Islam H, Moghaddam K (2022) The effect of female board representation on the level of ownership in foreign acquisitions. Corp Gov Int Rev 30(5):608–626

Asmussen CG, Nielsen B, Goerzen A, Tegtmeier S (2018) Global cities, ownership structures, and location choice: foreign subsidiaries as bridgeheads. Compet Rev 28(3):252–276

*Ávila HDA, Rocha AD, Silva JFD (2015) Brazilian multinationals’ ownership mode: the influence of institutional factors and firm characteristics. BAR-Brazilian Admin Rev 12:190–208

*Batsakis G, Singh S (2019) Added distance, entry mode choice, and the moderating effect of experience: the case of British MNEs in emerging markets. Thunderbird Int Bus Rev 61(4):581–594

Beckerman W (1956) Distance and the pattern of intra-European trade. Rev Econ Stat 38(1):31–40

Berry H, Guillén MF, Zhou N (2010) An institutional approach to cross-national distance. J Int Bus Stud 41(9):1460–1480

Beugelsdijk S, Kostova T, Kunst V, Spadafora E, van Essen M (2018a) Cultural distance and the process of firm internationalization. J Manag 48:89–130

Beugelsdijk S, Ambos B, Nell PC (2018b) Conceptualizing and measuring distance in international business research: recurring questions and best practice guidelines. J Int Bus Stud 49(9):1113–1137

Beugelsdijk S, Mudambi R (2014) MNEs as border-crossing multi-location enterprises: The role of discontinuities in geographic space. In: Cantwell J (ed) Location of international business activities. Palgrave Macmillan, London, pp 8–34

Blomstermo A, Deo Sharma D, Sallis J (2006) Choice of foreign economy entry mode in service firms. Int Mark Rev 23(2):211–229

Bittencourt GM, de Mattos LB, Borini FM (2017) Perfil do investimento direto externo das multinacionais estrangeiras no Brasil: aspectos transnacionais, setoriais e da firma. Economia Aplicada 21(4):681–708

Boateng A, Du M, Wang Y, Wang C, Ahammad MF (2017) Explaining the surge in M&A as an entry mode: home country and cultural influences. Int Market Rev 34(1):87–108

Bowe M, Golesorkhi S, Yamin M (2014) Explaining equity shares in international joint ventures: Combining the influence of asset characteristics, culture and institutional differences. Res Int Bus Finance 31:212–233

Briner R, Denyer D (2012) Systematic review and evidence synthesis as a practice and scholarship tool. In: Rousseau DM (ed) The Oxford handbook of evidence-based management. Oxford University Press, New York, pp 112–129

Brouthers K (2002) Institutional, cultural and transaction cost influences on entry mode choice and performance. J Int Bus Stud 33(2):203–221

Brouthers K (2013) A retrospective on: institutional, cultural and transaction cost influences on entry mode choice and performance. J Int Bus Stud 44(1):14–22

Brouthers KD, Brouthers LE (2003) Why service and manufacturing entry mode choices differ: the influence of transaction cost factors, risk and trust. J Manage Stud 40(5):1179–1204

Brouthers K, Hennart JF (2007) Boundaries of the firm: Insights from international entry mode research. J Manag 33(3):395–425

Canabal A, White GO (2008) Entry mode research: past and future. Int Bus Rev 17(3):267–284

Chan CM, Makino S (2007) Legitimacy and multi-level institutional environments: implications for foreign subsidiary ownership structure. J Int Bus Stud 38(4):621–638

Chan CM, Makino S, Isobe T (2010) Does subnational regional matter? Foreign affiliate performance in the United States and China. Strateg Manag J 31:1226–1243