Abstract

“Leader credibility” is believed by many scholars as essential for effective leadership and is commonly used in discussions about leaders in business, politics, and other areas. Yet despite leader credibility’s strong presence in contemporary press and research, the “leader credibility” construct is not clearly conceptualized, and a grounded understanding of leader credibility is missing. To begin building a solid foundation of leader credibility knowledge, we conducted a systematic literature review (SLR), which included 108 peer-reviewed articles representing various disciplines. This paper presents our descriptive and content-based findings. Our results reveal a significant research gap: despite the breadth and depth of the research on leader credibility, leader credibility is not consistently defined or measured. We provide an accounting of knowledge to date and illustrate this concept’s weak footing. Finally, we outline an array of relevant research paths that are possible after scholars reconceptualize the leader credibility foundation.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

For decades, researchers have studied leaders to identify the keys to successful leadership (e.g., Bass and Bass 2008; Landis et al. 2014). Some believed that great leaders were born rather than shaped by training or experience, and others advocated for a link between leader behaviors and the situation (e.g., Blake and Mouton 1985; Blanchard et al. 1993). Contemporary leadership theory has focused on the relationship between the leader, follower, and organization (e.g., McCauley and Palus 2021; Bass and Bass 2008). Researchers have found leader credibility as relevant to multiple contemporary leadership theories. For example, leader credibility is discussed as a moral component of transformational leadership behavior (Bass and Steidlmeier 1999), a factor differentiating authentic leaders from non-authentic leaders (Gardner et al. 2005), and a characteristic of servant leaders (Russell 2001; Russell and Stone 2002).

Our interest in leader credulity was prompted by the broad discussion of the topic in our classes and upon deeper reflection of the leader authenticity and leader credibility concepts, which overlap. Therefore, we conducted a scoping review of the literature and contemporary press to explore leader credibility as a construct. Scoping reviews often serve as a precursor to systematic reviews, illuminate key concepts/definitions, and identify potential knowledge gaps (Munn et al. 2018).

We also discovered leader credibility connected with the source credibility concept and Kouzes and Posner’s research of exemplary leadership and leader credibility. Source credibility has origins in communications research. Aristotle first espoused source credibility and explored how people evaluate a message’s source and how those evaluations impact message persuasiveness (Umeogu, 2012). For more than thirty years, Kouzes and Posner (2012) researched leadership, publishing their qualitative findings in two books, each with multiple editions. Kouzes and Posner advocated the importance of leader credibility, calling it the foundation of leadership. Our scoping review discovered that many scholars cite Kouzes and Posner’s work as the theoretical source of their leader credibility research. Very early, we questioned those potential leader credibility theory applications.

In addition, we found that leader credibility surfaced in peer-reviewed journals representing a wide range of disciplines: public administration (Grasse et al. 2014; Gabris et al. 2001), business strategy (Salicru and Chelliah 2014), economics (Komai and Stegeman 2010), business management (Chun et al. 2014; Kouzes and Posner 2005), sports management (Swanson and Kent 2014), political science (Myerson 2008; Van Zuydam and Hendriks 2018), medical and health services (Davidhizar 2007; Loh et al. 2016), education (Bolkan and Goodboy 2009; Holland 1997), and psychology (Sweeney et al. 2009). Empirical research has explored relationships between leader credibility and various outcomes, such as leader self-awareness (Grasse et al. 2014), subordinate burnout (Gabris and Ihrke 1996), managerial innovation (Gabris et al. 1999), motivating language (Holmes and Parker 2017), subordinates’ perceived cost of seeking feedback (Chun et al. 2014), and affective well-being at work (Rego and Pina e Cunha 2012).

Our review of the contemporary press also revealed that leader credibility is a popular concept. An internet search for “leader has credibility” yielded over 9900 results, a search for “leader has lost credibility” produced over 2000 results, and a search for “build credibility as a leader” generated over 100,000 results. Leader credibility is often discussed in media. For example, Angela Merkel lost credibility and became less popular because of Euro-related decisions (Nixon 2011), yet during the Covid-19 pandemic, her science background enhanced her credibility (Miller 2020). Mark Zuckerberg's testimony to Congress, in which he acknowledged Facebook was sharing users’ data without consent, damaged his credibility (Alaimo 2018). Martin Winterkorn, Volkswagen's former CEO, gained credibility when he presented the vision of Volkswagen becoming the world’s number one automaker (Stein 2009). However, Volkswagen’s diesel scandal, intentionally cheating on U.S. emission tests, threatened Winterkorn’s and other Volkswagen leaders’ credibility (Fleming 2015). Winston Churchill’s leader credibility was enhanced through a tone of defiance while being realistic (Abadir 2020). Warren Buffet’s well-known transparency and integrity reputation enhanced his leader's credibility (Lissauer 2005).

The contemporary press also discusses the benefits of leader credibility and the harms of not having leader credibility (e.g., Murphy 2016; Sinha 2020). For instance, contemporary press articles propose benefits from leader credibility, including higher organization productivity and performance, stronger relationships, and better leader well-being. Proposed harms from the lack of leader credibility include low employee morale, employees merely following rules and not fully engaging in their work, and the lack of genuine followers. Clearly, leader credibility, or its absence, draws ample attention in contemporary press.

From this initial scoping review, we observed that leader credibility often appeared in the academic literature as a proven and well-established construct. Still, we found inconsistencies in how the construct is defined and detected overlap with other constructs such as trust and authenticity. Consider these two examples: Leader credibility “is present when leaders are perceived by their followers as believable, as men and women of their word, and as persons who can be followed and trusted (Gabris et al. 2000, p. 489)”; and "A credible leader possesses character (ethical, honest, loyal, respects others) and is recognized as competent (accountable and gets results) (Tremaine 2016, p. 137)." The first definition applies trust, but the second applies character. Are trust and character the same constructs? The second definition includes competence, but the first does not. Can followers see a believable, but incompetent, leader as credible?

This initial review prompted us to conduct a systematic literature review (SLR) to understand better how leader credibility is defined and identify its theoretical connections. “SLRs synthesize a foundation of knowledge including all related material, presenting both what exists and identifying what is missing (Williams Jr. et al. 2021, p. 523).” SLRs provide a transparent, objective overview of existing knowledge of a given topic that answers research questions from a comprehensive and objective examination of existing literature (Brereton et al. 2007; Clark et al. 2021; Siddaway et al. 2019; Tranfield et al. 2003). SLRs do not seek to support proposed hypotheses, which is the aim of traditional literature reviews. In contrast, it is a technique to achieve “sensemaking,” a process for transforming abstract meanings into concrete forms (Weick et al. 2005; Rojon et al. 2021).

2 Methodology

Our SLR process followed Tranfield et al. (2003) and Fisch and Block’s (2018) recommendations for conducting an SLR. We used this methodology to understand better the complete nature of the leader credibility concept and related research. We began with the following research questions:

-

(1)

What is the theoretical basis of leader credibility?

-

(2)

How is leader credibility defined?

-

(3)

How is leader credibility measured?

-

(4)

What outcomes, antecedents, and moderators are related to leader credibility?

We systematically identified the relevant literature to generate a vast pool of articles for possible inclusion in our SLR. We limited our search to peer-reviewed journals because we saw merit in assessing higher-quality material that had undergone the peer-review process (Podsakoff et al. 2005). We did not restrict our search to publication dates or specific academic fields. For instance, we did not limit our search to leadership or business-oriented literature.

To increase the probability of having a complete list of SLR inclusion candidates and reduce the chance of missing a relevant piece, we utilized three search databases: Google Scholar, ABI/INFORM, and ProQuest. As each search database produced different lists, using three search databases was an effective approach that yielded a more thorough examination of the literature. We searched for “leader” and “credibility,” or “leadership” and “credibility” as search terms in titles, abstracts, or keywords. After evaluating our initial results, and to reduce the chance of missing a relevant piece, we broadened our search by applying only “credibility” as a search word in titles, abstracts, or keywords. To determine if an article merited consideration for SLR inclusion, we scanned the article for evidence of a leader credibility discussion or a related empirical study. Our search produced 278 SLR potential inclusion candidates. Each of the 278 possible inclusion articles was randomly assigned to two researchers from our four-person team.

Since researchers apply “credibility” in various paradigms [e.g., witness credibility (Kaufmann et al. 2003), celebrity credibility in advertisements (Goldsmith et al. 2000), internet information credibility (Flanagin and Metzger 2000), and source credibility (Ohanian 1990)], our first criterion for inclusion in our review was to ask, “Did the article address leader credibility?” If the answer was “no,” the article was excluded. As an illustration, we included an article discussing source credibility only if it contributed to leader credibility knowledge. For example, Holmes and Parker (2017) applied source credibility in discussing credible leaders’ communication, so we included that article. Conversely, Son and Kim (2016) explored source credibility’s effect on employee feedback acceptance, but they did not specifically examine leader credibility, so we omitted that article in our SLR.

For inclusion, the article needed to meet at least one of the following criteria: the article included a leader credibility definition, or the article was an empirical study in which leader credibility was explored, or leader credibility surfaced in findings. In summary, first, if an article was not leadership-oriented, it was excluded. And second, if the article was leadership-oriented but did not have a leader credibility definition or did not include leader credibility empirical research, it was excluded.

We applied the following tactics to ensure inter-rater reliability and consistently adhere to our inclusion criteria. First, we assigned each article to two research team members (out of four total members), who assessed the article’s potential for inclusion and individually chronicled material related to our research questions. Our research team pairings rotated in working through the 278 articles. If two team members had differences concerning an article’s inclusion, our entire team assessed the article, seeking common ground. Team members did not apply a scale in judging articles for inclusion/exclusion. Our team approached this in a dichotomous manner, include or exclude.

After initial article reviews, we discussed each article in face-to-face meetings and collectively chronicled material related to our research questions. This approach caused multiple, in-depth discussions focused on the inclusion criteria and resulted in unanimous decisions on including or excluding articles [see Clark et al. (2021) for a deeper discussion of team review benefits]. From our extensive review of 278 articles in the SLR candidate pool, our team agreed on the rejection of 170 articles and the inclusion of 108 articles in our SLR. Figure 1 illustrates our SLR protocol.

3 Literature analysis and synthesis

We analyzed the literature from our SLR from descriptive and content perspectives to address our research questions.

3.1 Descriptive analysis

Although we did not limit our search to a specific time period, the 108 articles’ publication dates span from 1970 to 2021. Figure 2 illustrates the number of articles in our SLR published in seven-year increments and suggests leader credibility research has grown over the last fifty years.

As expected from our initial scoping review, leadership or management journals published many of the articles in our SLR. However, as illustrated in Fig. 3, peer-reviewed journals from a variety of other fields published articles meeting our inclusion criteria, including the following: hotel and restaurant industry, military, research technology, strategy, communication, industrial training, political science, organizations, business, ethics, human resources, health services, psychology, education, and public administration. Yet, as Fig. 3 shows only fields with two or more articles in our SLR, it does not fully illustrate the number and the variety of fields represented in our SLR, which shows leader credibility research’s breadth. Indeed, articles from twelve other fields, not shown in Fig. 2, surfaced in our SLR, including defense, corporate reputation, economics, emergency services, the legal field, marketing, policing, public relations, religion, safety, sports management, technology management, and youth services. Our SLR articles represent 29 fields, indicating that leader credibility is relevant to a wide array of leadership environments.

There were four fields, other than leadership and management, with relatively high numbers of articles in our SLR. Thirteen articles surfaced from the public administration field with topics such as the following: the importance of leader credibility in city managers (Grasse et al. 2014), leader credibility and federal employee burnout (Gabris and Ihrke 1996), leader credibility and city employee innovation (Gabris et al. 1999), leader credibility and leader rank in a federal agency (Gabris and Ihrke 2007), leader credibility and employee acceptance of performance evaluation (Gabris and Ihrke 2000), and how women in federal agencies gain leader credibility (Rusaw 1996). Ten articles in our SLR surfaced from education, including the following themes: previous teaching and research as vital for higher education leadership credibility (Spendlove 2007), teacher credibility as a component of classroom leadership (Balwant 2016; Bolkan and Goodboy 2009), and the importance of principals’ leader credibility (Beam et al. 2016; Gale and Bishop 2014; Holland 1997; Northfield 2014). Eight articles from the psychology field met our inclusion criteria, including the following findings: leader credibility’s positive relationship with affective well-being at work (Rego and Pina e Cunha 2012), followers trusting leaders with high credibility (Sweeney et al. 2009), and external coaches have higher leader credibility than peers from inside an organization (Sue‐Chan and Latham 2004). The health services field published six articles in our SLR. One topic addressed was the importance of credibility when a doctor or nurse steps into leadership (e.g., Loh et al. 2016; Upenieks 2003). This further illustrates leader credibility’s relevance in several fields and the breadth of its research.Footnote 1

3.2 Content analysis

3.2.1 Theoretical connections and observations

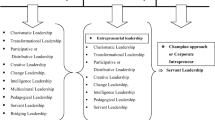

To better understand the development of the leader credibility construct, we captured the theoretical basis applied for leader credibility for the articles included in our SLR. Analysis of 108 leader credibility articles revealed two dominant theoretical streams: (1) source credibility theory and (2) Kouzes and Posner’s exemplary leader and credibility work. Of our review’s 108 leader credibility articles, 49 (45.4%) applied the Kouzes and Posner stream, and 29 (26.9%) applied the source credibility stream. Multiple articles applied both (e.g., Holmes and Parker 2017; Kouzes and Posner 2005; Lafferty 2004; Russell and Stone 2002; Swanson and Kent 2014; Van Zuydam and Metze, 2018).

Source credibility theory. The concept of source credibility originated in Aristotle’s work, The Rhetoric, in which he explored how people evaluate a message’s source and how that evaluation impacts message persuasiveness (Umeogu 2012). Aristotle proposed three elements of persuasion: ethos, logos, and pathos. He theorized that ethos was composed of a speaker’s intelligence, moral virtue, and goodwill towards the audience.

Hovland et al. (1953) operationalized source credibility by studying the impact of informants’ credibility on their ability to persuade and proposed two elements: the speaker’s trustworthiness and expertise. Other researchers also operationalized source credibility as trustworthiness and expertise (e.g., Sternthal et al. 1978; O’Keefe 1990). Andersen (1961) and Berlo et al. (1969) introduced dynamism to the credibility construct, which Hackman and Johnson (1996) supported. Ohanian (1990, p. 41) defined source credibility as a “communicator's positive characteristics that affect the receiver's acceptance of a message.”

McCroskey and Teven (1999) anchored their leader credibility studies to source credibility, creating leader credibility measures exploring three components: expertise, trustworthiness, and goodwill. Returning to Aristotle’s work, the goodwill element captured how much the speaker cared for, or had good intentions towards, others. However, McCroskey and Teven (1999) did not include the dynamism element.

It is important to note that source credibility’s origin focused on a speaker’s ability to communicate and persuade. However, modern discussion of leader credibility incorporates much more than speaking and persuading. Table 1, which is included at the end of this section, presents an overview of the leader credibility theoretical foundations we observed. As shown in Table 1, 29 articles in our SLR ground leader credibility research in the source credibility concept.

Kouzes and Posner’s exemplary leader and credibility work. Because scholars frequently cite Kouzes and Posner in leader credibility research, we looked closely at their work and its relation to leader credibility. For more than thirty years, Kouzes and Posner researched leadership, primarily publishing their qualitative findings in two books, each with multiple editions: The Leadership Challenge: How to Make Extraordinary Things Happen in Organizations (2012) and Credibility: How Leaders Gain and Lose It and Why People Demand It (2011). Only three articles authored by Kouzes and Posner surfaced in our SLR search, and two met the inclusion criteria. In 1988, Posner and Kouzes shared the results of a study correlating three dimensions of source credibility (trustworthiness, expertise, dynamism) with their five practices of exemplary leaders. This article has only ten references, of which two refer to their work. Kouzes and Posner’s (2005) other article in our SLR provides advice on leading during cynical times. They espouse that credibility is the foundation of leadership and propose traits of admired leaders (honest, inspiring, and competent) are similar to source credibility. They support their work with twelve references, two of which are their books. Kouzes and Posner (2005) provide only one reference defining source credibility.

Kouzes and Posner’s (1987, first of many editions) book, The Leadership Challenge: How to Make Extraordinary Things Happen in Organizations, stems from their research of exemplary leadership, the book's focus. Kouzes and Posner began by asking people about their best leadership experiences. From analyzing thousands of personal accounts, they grouped behaviors exhibited by effective leaders into five practices: model the way, inspire a shared vision, challenge the process, enable others to act, and encourage the heart. In discussing the five practices—and building on research from another qualitative research stream, which we discuss next—they proposed the importance of leader credibility. Kouzes and Posner continued collecting data for over thirty years, and based on their findings, and they updated The Leadership Challenge with multiple editions (2012).

Additionally, Kouzes and Posner (2017) asked people what they look for and admire in a person they are willing to follow. Respondents consistently indicated the four most important attributes: honest, competent, forward-looking, and inspiring. Kouzes and Posner argued that three of these four attributes—honest, competent, and inspiring—aligned with the key characteristics of “source credibility,” which they defined as perceived trustworthiness, expertise, and dynamism. Accordingly, Kouzes and Posner (2011) contend that leader credibility consists of three attributes: honest, competent, and inspiring. Subsequently, they wrote a book titled Credibility: How Leaders Gain and Lose It and Why People Demand It (2011), which argues that credibility is the foundation of leadership. This work focuses on how leaders can earn and sustain credibility by incorporating the five exemplary leadership practices, which makes a differentiation between exemplary leadership and leader credibility difficult. In Kouzes and Posner’s latest version of this book, they specifically added questions about credibility to their qualitative exploration. Many articles in our SLR cite Kouzes and Posner’s credibility research. Yet much of what they write about credibility is based on the “most admired leader characteristics” rather than specifically on leader credibility. Furthermore, some authors generally applied Kouzes and Posner’s work without specifying which source or edition they applied (e.g., Abu‐Tineh et al. 2008; Gabris and Ihrke, 1996; Gabris et al. 2001; Grasse et al. 2014; Von der Ohe et al. 2004).

It is necessary to understand which work leader credibility researchers used to ground leader credibility because Kouzes and Posner’s characterization of credibility and its relationship with the exemplary leadership practices appears to have evolved over time. Early on, Kouzes and Posner described credibility as consisting of admired leaders’ four top characteristics (honesty, inspiring, competent, and forward-looking). In other writings, Kouzes and Posner drop the forward-looking characteristic, making the case that three of the four characteristics (honesty, inspiring, competent) match the source credibility elements: trustworthiness, expertise, and dynamism. However, their works do not provide a deep theoretical exploration of credibility from literature, but instead, they focus mainly on their qualitative studies’ findings. They provide a single footnote in the two editions of Credibility (1993, 2011), citing Berlo et al. (1969) for defining source credibility as having those three elements.

Kouzes and Posner’s characterization of leaders did not limit other researchers’ use of their work as a foundation for leader credibility research. Recall that 45% of the articles in our SLR ground their credibility studies or discussion in Kouzes and Posner’s work. Gabris and Mitchell (1991) operationalized Kouzes and Posner’s qualitative work and credibility description by creating leader credibility measures. Their scale focused on exemplary leaders' behaviors to build credibility, and Gabris, Ihrke, and other colleagues used that scale for over two decades. Gabris or Ihrke were authors of eleven articles included in our SLR.

We present in Table 1 the following Kouzes and Posner leader credibility theoretical sub-streams: studies primarily relying on exemplary leadership practices, studies based on the credibility work primarily, and studies generally focused on Kouzes and Posner’s collective leadership work. As shown in Table 1, although Kouzes and Posner’s work lacks a stated theoretical or methodological basis beyond the initial qualitative exploratory work, it appears many researchers have adopted their work as settled leader credibility theory–which we identify as source amplification.

3.2.2 Leader credibility definitions and observations

Our extensive SLR confirmed our perception from our scoping review that leader credibility is not consistently defined. To illustrate the variety of definitions, consider the following. Farling et al. (1999) described leader credibility as “…the quality that enables one to be believed and also involves the trustworthiness and reliability of information of communication received from a person” (p. 57). However, Bolkan and Goodboy (2009) applied competence and goodwill in addition to trustworthiness to describe leader credibility. Furthermore, Sweeney et al. (2009) pursued a different path, using dependable character in their definition. The variety of terms applied to describe leader credibility in these well-cited articles illustrates the lack of a clear definition of “what is leader credibility.”

Table 2 provides 12 examples of explicit leader credibility definitions from our SLR that appear in peer-reviewed journals from various disciplines: leadership, psychology, business, public relations, military, and safety management. The 12 definitions include an array of elements: perception, competence, trust, believability, character, ability, expertise, dependability, and honesty. There are some consistent elements. For example, 9 of the 12 definitions specifically include some version of “trust.” Half of the definitions include expertise or competence as a definition component. However, there are many differences. For instance, only one article mentions reliable communication (Farling et al. 1999). Only two articles (Balwant 2016; Posner and Kouzes, 1988) include the convincing or inspiration concepts, and a different two of the entries (Sweeney et al. 2009; Tremaine 2016) apply character as a broader concept.

Differing leader credibility definitions compound the confusion and ambiguity between leader credibility and other concepts. For example, trust and credibility are often combined as one concept or treated as very similar ideas (e.g., Bass and Steidlmeier 1999; Carrillo 2002; McAllister 1995; Newman et al. 2014; Rego and Pina e Cunha 2012; to name a few). For instance, in research conducted on cognitive and affective trust-based mechanisms (Newman et al. 2014), trust is broken down into cognitive trust, defined as “trust from the head” (p.115), and affective trust, which is “trust from the heart” (p.115). Cognitive trust is derived from rational assessments of personal characteristics and is determined by performance track records, which is often viewed as credibility. Indeed, McAllister (1995) proposed that cognitive trust is determined by the credibility of the exchange partner, directly connecting these two constructs. The consistent use of trust and credibility together leads to construct confusion.

To further illustrate trust and leader credibility definition confusion, consider the portrayal of Jean Monnet as a servant leader (Birkenmeier et al. 2003). The authors’ credibility and trust definitions are very similar: credibility includes “worthy of belief, to believe, to put faith in” (p. 385); trust includes “confidence, a reliance…on the integrity, veracity, justice, friendship, or other sound principle of another person or thing” (p. 388). As another example, Simons’ (1999) article on transformational leadership and integrity states, “Transformational leadership often relies on charismatic leadership, and charismatic leadership requires trust and credibility among employees.” Additionally, “…the development of trust and credibility among employees requires behavioral integrity” (p. 92). It appears Simons applies “trust and credibility” as one over-arching concept and ties them directly to another similar term, integrity. Related, Rego and Pina e Cunha (2012) measured “trust and credibility of leaders” as one construct. Furthermore, Sweeney et al. (2009) found through exploratory factor analysis and confirmatory factor analysis that items measuring leader credibility and leader trust were redundant and best combined into one construct. However, in multiple studies from our SLR, trust and credibility are treated as separate concepts (e.g., Bolkan and Goodboy 2009; Bhindi and Duignan 1997; Holland 1997; Rusaw 1996).

For another example of the ambiguity between credibility and other concepts, consider the following statements from Worden’s (2003a) discussion of integrity: “…integrity as a mediator within strategic leadership and its impact on credibility” (p. 31); “integrity…can provide the credibility necessary for a positive reputation” (p. 31); “for the moral self-governance necessary for integrity to have credibility…” (p. 35); “Products of integrity, such as credibility and trustworthiness, are important to effective leadership…”(p. 36); and, “Indeed, credibility goes on to play a vital role in the reputational capital amassed by the exercise of integrity in strategic leadership” (p. 36). The first phrases suggest integrity impacts credibility, integrity can provide credibility, integrity can have credibility, and integrity produces credibility and trust. Yet, the last statement implies credibility is vital in exercising integrity. This example indicates a circular relationship between these concepts. This is possible for these related constructs, but a clear and consistently used leader credibility definition will help provide clarity. In summary, scholars apply different concepts in defining and describing leader credibility, and they use credibility to define and describe many of these same concepts.

Existing literature does not seem to acknowledge the inconsistencies. This may represent the nomological value of the multiple leader credibility definitions–everything fits and seems to make sense. Although leader credibility is not consistently defined, researchers in many fields have studied it as if it is. Without a consistent definition, the literature discusses leader credibility as a proven truth or dogma. However, a consistent leader credibility definition is needed for valid and reliable research. Hopefully, the present study highlights this previously unrecognized and vital research gap.

3.2.3 Leader credibility measures and observations

To further paint a picture of the current state of leader credibility research, we explored sources for items used to measure leader credibility in quantitative research. We found 13 studies that implemented credibility measurement items drawn from different sources. In other words, those 13 articles applied leader credibility measures from sources not used in other articles. For instance, in exploring subordinates’ feedback-seeking behavior, Chun et al. (2014) measured leader credibility using Fedor et al.’s (1992) items to measure leader expertise. Also, in research of combat leadership, Sweeney et al. (2009) applied Kelley and Thibaut’s (1978) leader trust measures. No other quantitative leader credibility study in our SLR applied Fedor et al.’s (1992) or Kelley and Thibaut’s (1978) measures. In our SLR, 13 empirical studies applied measures created by the author(s) rather than relying on existing measures. For example, to assess leader credibility, Chng et al. (2018) applied indicators of competence and trust items, which it appears they developed and applied.

Kouzes and Posner’s work and McCroskey and Teven’s (1999) source credibility research, discussed in-depth earlier, have the most substantial presence in leader credibility measurement. Twelve studies applied items from Kouzes and Posner, which are based on their qualitative research and published in two books (2012; 2011). Examples include the following: Grasse et al.’s (2014) study of variations in city-leaders’ credibility; Abu‐Tineh et al.’s (2008) study of credibility and transformational leadership of Jordanian school principals; and Lee’s (2011) study of preferred leadership characteristics, including credibility, among South African managers. Although Kouzes and Posner’s work is applied frequently in leader credibility research, as we stated earlier, most of their leader credibility research is not published in peer-review journals.Footnote 2 However, articles that used Kouzes and Posner’s work as a foundation cited different versions of their work, creating greater variation in leader credibility conceptualization. Five studies applied McCroskey and Teven’s (1999) source credibility items, including Bolkan and Goodboy’s (2009) study of credibility and transformational leadership in the classroom and Basford et al.’s (2014) study of followers’ reaction to credible leaders’ apologies. Figure 4 illustrates the number of leader credibility measurement items drawn from the four source groups we described above, and Appendix 1 provides a detailed list.

Figure 5 illustrates the 19 most used leader credibility measurement items found in our SLR, highlighting that leader credibility measurement items are inconsistent. Apparently, researchers have not applied established methods to develop leader credibility measurement items [e.g., multiple questionnaire administrations, factor analysis, internal consistency assessment, construct validity, and replication (Hinkin 1995; MacKenzie et al. 2011)]. The state of leader credibility measures prompts one to question the rigor of leader credibility’s quantitative research incorporating those measures.

3.2.4 Leader credibility research depth: Outcomes, antecedents, and moderators

The 72 empirical studies in our SLR included 31 qualitative and 43 quantitative studies. Two studies, Kim et al. (2009) and Beam et al. (2016), applied both qualitative and quantitative methods. The following summary includes multiple examples, yet it does not provide an all-inclusive synopsis of all leader credibility empirical studies in our SLR. We provide examples that reflect the general nature of what we see in leader empirical credibility research. In addition, we share a detailed list of antecedents, moderators, and outcomes discovered in our SLR in Table 3. Given that the items listed in Table 3 are context-specific, we include the research context.

Multiple studies indicate leader credibility positively impacts various workplace outcomes. Those outcomes include the following: performance appraisal acceptance (Gabris and Ihrke 2000), believability in a leader’s apology (Basford et al. 2014), less follower burnout (Gabris and Ihrke 1996, 2003), transformational leadership (Balwant 2016; Bolkan and Goodboy 2009), innovation (Gabris et al. 2001, 1999, 2000), and motivating leader language (Holmes and Parker 2017). Findings also indicate leader credibility outcomes include employee communication interpretations (Harshman and Harshman 1999) and societal reputation (Worden 2003b).

Numerous studies identified attributes of effective leaders through a deductive approach–starting with a general idea (effective leadershipFootnote 3) and digging down to identify specifics (the attributes of effective leaders). The studies sought effective leader attributes in various contexts: education (Gale and Bishop 2014; Ryan and Tuters 2017; Spendlove 2007); the medical field (Chaffee and Mills 2001; Loh et al. 2016; Patterson and Krouse 2015; Upenieks 2003); politics (Van Zuydam and Hendriks 2018; Van Zuydam and Metze 2018); social resistance (Einwohner 2007); government (Paton and Goel 1993); and business (Harshman and Harshman 1999; Worden 2003b). These studies’ environments included the following: school administrators in their early years of leadership (Northfield 2014), resistance activities in Nazi-occupied Jewish ghettos (Einwohner 2007), policing (Grint et al. 2017), and large/complex organizations (Harshman and Harshman, 1999). It is essential to recognize that researchers were not seeking effective leadership as a leader credibility output, but leader credibility surfaced in their findings. Five quantitative studies (Cichy et al. 1993, 1992; Cichy and Schmidgall 1996; Lee 2011; Tremaine 2016) support the deductive findings of leader credibility as a component of effective leadership. Phrased differently, the research found effective leadership as an output of leader credibility. These findings of leader credibility as an attribute of effective leadership in various environments exemplify the importance of leader credibility.

Two leader credibility antecedents found in our SLR were competence (Bradley-Levine 2011; Garst et al. 2019) and character (Jones and Kriflik 2005; Kim et al. 2009). Experience or education enhances perceived competence (Bradley-Levine 2011; Garst et al. 2019). Behavioral attributes, such as trust and integrity, develop perceived character (Jones and Kriflik 2005; Kim et al. 2009). In addition, findings indicate that presenting a vision for change (Denis et al. 1996) and acting in caring and daring manners (Haake et al. 2017) builds leader credibility. Multiple studies (e.g., Denis et al. 1996; Van Zuydam and Hendriks 2018; Van Zuydam and Metze 2018) emphasized that building credibility is a continual work in progress.

A few leader credibility moderators surfaced. For instance, one study presented international culture as impacting leader credibility; a leader who had credibility in the United States did not have leader credibility in the European culture (Baumgartner 2009). Two studies explored challenges women experience when attempting to build leader credibility in male-dominated environments, where women feel a need to assume male attributes to assert their credibility (Haake et al. 2017; Rusaw 1996). One study explored how the extent of work experience moderated physical attractiveness’ effect on perceived sales manager credibility and found that physical attractiveness enhanced more experienced salespeople’s view of a sales manager more than less experienced salespeople (Chaker et al., 2019).

In summary, findings from empirical studies in our SLR suggest the importance of leader credibility in research and in practical application. Leader credibility research has explored many outcomes and antecedents, reinforcing its depth and relevance. However, are these findings valid without a consistent leader credibility definition and valid measures?

3.2.5 Overall review analysis and observations

From the collective knowledge about leader credibility research, our SLR sheds light on multiple gaps and vulnerabilities. First, leader credibility often appears anchored to source credibility or Kouzes and Posner’s work. Therefore, leader credibility’s theoretical grounding seems narrow. We did not see concern among researchers over leader credibility’s weak theoretical basis; rather, they took what was published as sufficient grounding. Second, the SLR reinforced our premise that although leader credibility is discussed often in non-research settings and many academic fields, leader credibility is not well defined and is confused with other concepts. Third, the SLR confirmed the breadth of leader credibility research. This relevant leadership topic is researched in many academic fields. Fourth, leader credibility research is relatively deep, having explored multiple outcomes and antecedents. And fifth, although peer-reviewed journals have published 43 leader credibility quantitative studies, leader credibility measures are inconsistent, reflect many elements, and are not developed through research.

SLRs can only paint a picture from what is present in research, and an SLR cannot create quality from a body of work that lacks rigor (Williams Jr. et al. 2021). However, the SLR process does allow researchers to assess the quality of the articles included in an SLR. The management field primarily assesses quality based on the publication source; and there are multiple articles published in notable journals in our SLR, and several are highly cited. We acknowledge that articles with varying levels of academic rigor exist in our SLR, which is a common problem in SLRs (Rojon et al. 2021). However, since we were taking a holistic view and conducting a broad examination of the leader credibility concept as presently presented, we chose not to reject articles based on quality or journal ranking. We support the call by SLR scholars to evaluate the quality of articles included in an SLR beyond using peer-review journals as the primary method and encourage the identification of methods to do so (Briner & Denyer 2012; Williams Jr. et al. 2021).

4 Future research agenda

4.1 Analyze theory applied in current leader credibility research

The SLR revealed two primary sources of leader credibility theory (source credibility and Kouzes and Posner’s exemplary leader and credibility work). However, rather than thoroughly exploring and testing those assumed foundations, many authors of articles in our SLR anchored their work to source credibility or Kouzes and Posner and moved on. Researchers did not question whether anchoring leader credibility to source credibility or Kouzes and Posner’s work was sufficient. In leader credibility research employing Kouzes and Posner, it is often hard to discern whether the grounding was based on leader credibility and its components or if the grounding was a mixture of what makes a leader exemplary versus what makes a leader credible. Some of the leader credibility measures based on Kouzes and Posner’s work seem to measure the behaviors of exemplary leaders rather than credibility. As discussed by researchers re-examining the development of leader authenticity research (Gardner et al. 2021), the conceptualization of authentic leaders includes antecedents and outcomes lumped together and a blurring of similar concepts. We see the same issues with the leader credibility theory development. Analyzing the current leader credibility theoretical bases applied in research may form an initial step for building a solid theory. Effective theories help us understand the world (Tesser 2000). A better understanding of the scope and complexity of leadership is possible through leader credibility theory development.

Possible research questions related to the theoretical underpinnings of leader credibility include the following:

-

How do Kouzes and Posner conceptualize leader credibility in their qualitative studies, and is leader credibility different from exemplary leadership and the five practices, or have they merged these concepts?

-

What role does source credibility play in the conceptualization of leader credibility?

-

How does leader credibility theory merge with or differentiate from related concepts (e.g., authenticity, trust, integrity, servant leadership)?

4.2 Form a leader credibility definition

In developing a leader credibility definition, researchers could do qualitative work applying a positivist approach, which seeks a “real world” understanding of leader credibility (Meyers 2013). For example, in seeking to define “wisdom,” Hershey and Farrell (1997) sought characteristics of wise individuals from laypersons. Multiple approaches are appropriate in drawing leader credibility definition knowledge from followers. Consider the following (described in the context of defining leader credibility): ask participants to share characteristics of leaders with credibility; give participants a list of potential credible leader attributes and request a ranking; or ask participants to identify public leaders with credibility and then study the attributes of those leaders (Hershey and Farrell 1997). Much of Kouzes and Posner’s work started from this approach, but since a large portion of their work has occurred outside the peer-review process, it is hard for researchers to evaluate, replicate, and build on what they have done.

Additionally, researchers could conduct an extensive review of current leader credibility definitions in the literature, similar to Iszatt‐White and Kempster’s (2019) SLR focused on re-grounding the authentic leadership construct. Researchers may code various phrases and terms applied for leader credibility definitions in the literature. From their coding, researchers may build a leader credibility definitional model. Following Walumbwa et al.’s (2008) work directed at defining authentic leadership, once leader credibility elements are drawn from qualitative research or through an SLR, researchers could survey stated items and phrases and apply confirmatory factor analysis to test leader credibility’s multidimensional nature and identify any higher-order constructs.

To resolve the definition confusion discussed above, researchers should focus on clarifying similar constructs such as honesty, trust, and integrity to determine how they differ in the context of leadership. Furthermore, studying each of the constructs as they relate to leaders would prove very valuable to better understand the relationships between these terms. By doing so, researchers could help eliminate the confusion among these related leadership constructs and provide more clarity for research of leader qualities.

Potential research questions regarding developing a leader credibility definition include the following:

-

What does leader credibility mean to people?

-

What does it mean to say a leader has credibility?

-

What traits or qualities do leaders with credibility demonstrate?

-

What concepts or words are most used in the literature when defining leader credibility?

4.3 Develop leader credibility measures

Once a reliable leader credibility definitional model is developed, scholars should develop valid and reliable leader credibility measures. While there has been considerable leader credibility empirical research conducted, researchers have not applied consistent leader credibility measures. In fact, in many cases, credibility surfaced as an important research item after the fact and was not initially included as a research construct. A formal measure development process is needed to produce a sound research construct. This process would likely include possible item identification, multiple questionnaire administrations of these items, factor analysis, internal consistency assessment, construct validity, and replication (Hinkin 1995; MacKenzie et al. 2011). Researchers may apply developed measurement items to explore the relationship between leader credibility and logical construct outcomes. This process would require further testing of measurement items’ validity and reliability, discriminant validity, and a developed definition’s nomological validity (Cooper et al. 2005; Hair et al., 2010). The process of validating and developing valid and reliable measures will build leader credibility knowledge and further resolve the confusion between similar constructs.

General research questions include the following:

-

What are valid and reliable measures of leader credibility?

-

How do these measures differ from accepted measures of related constructs such as honesty, trust, and integrity?

-

How do these measures apply in different contexts?

4.4 Identify leader credibility antecedents and moderators

Leaders are motivated in different ways, including selfish desires or self-sacrificing, altruistic aspirations (Avolio and Locke 2002). Researchers might explore if leader motivation is an antecedent to leader credibility. For instance, researchers may study the connection between a leader’s selfish motivation and leader credibility perception. Researchers have questioned the relevance of charisma to transformational leadership (Williams Jr. et al. 2018). Related, future research may examine whether a leader’s charisma affects leader credibility perception building. Researchers may find different leader motivations or charisma as leader credibility antecedents or not as leader credibility antecedents.

Researchers may explore what impacts followers’ leader credibility perceptions from a moderating view. As an illustration, consider “e-leadership,” which reflects the movement of leaders’ use of face-to-face encounters to information and communication technologies (Van Wart et al. 2019). Related to building credibility, researchers may investigate the following: do personal, face-to-face encounters build leader credibility more so than online communication; is that relationship different among various age groups; and does e-leadership diminish the perception of leader credibility.

Future research might explore if leader credibility differs in perception across various situational, environmental, and cultural leadership settings, and, if so, how. We previously mentioned that leader credibility is situational. This is illustrated in our introduction by Merkel’s loss of leader credibility in Euro-rated decisions, but in contrast, her gain of leader credibility when dealing with Covid-19. The perception of leader credibility may fluctuate depending on the environment or situation. For instance, consider from our introduction Winterkorn’s (Volkswagen CEO) decision to intentionally cheat on U.S. emission tests, affecting 11 million vehicles. Is it possible that while the unethical act was happening, Volkswagen’s culture prompted followers to see their leaders as credible? A culture rooted in “doing anything to win” may fog the view of leader character. Certainly, organizational structures vary, reflecting different levels of formality and hierarchy. Research indicates higher respect for leaders in more hierarchical organizations (Fernandez 1991). Similarly, future research may explore the relationship between organizational hierarchy or structure and leader credibility perception. That study may resonate in today’s movement toward flatter organizations and more delegation.

Rusaw (1996) explored how women in federal agencies gain leader credibility. A sound definition and measures may enable replication of that work with more rigor from a general context, seeking to discern how diversity in the workplace–gender, ethnicity, or international origin–moderates leader credibility perception. Related to the international origin, investigators may investigate how leader credibility differs in various international cultures. For instance, is leader credibility as connected to outcomes in countries with high power distance (Hofstede 2001) as in countries with low power distance.

Future research may also investigate how changing leadership situations affect the perception of leader credibility. Consider an entrepreneur who must learn to distribute leadership as the company grows (Cope et al. 2011). Future research may explore the temporal evolution of small and mid-size enterprise leaders’ credibility as they progress through distributing, or not distributing, leadership.

Potential research questions in this area include the following:

-

How does a leader build others’ perception of their credibility?

-

What factors or actions can diminish a leader’s credibility?

-

How does leader motivation impact others’ perception of their credibility?

-

How does charisma impact others’ perception of leader credibility?

-

What environmental or situational factors impact the leader’s credibility?

-

Does personal, face-to-face encounters build leader credibility more than online communication?

4.5 Identify leader credibility-related outcomes

As another future path, researchers may study leader credibility’s effect on performance-related outcomes. Performance assessment may fall into various levels: follower, group, or organizational. For instance, are followers of credible leaders more committed to the organization? Are groups working under credible leaders more innovative? And do organizations with credible leaders produce more substantial financial outcomes?

As mentioned in our discussion of leader credibility empirical research, multiple studies applying a deductive approach found leader credibility as a component of effective leadership, reflecting influencing others and producing results (Yukl 2012).Footnote 4 Again, these studies were not seeking leader credibility as an element of effective leadership, but it surfaced. A consistent definition with valid measures may enable replication of that work through testing effective leadership as an outcome of leader credibility. A confirmed definition and valid measures may facilitate the exploration of leader credibility as a component or antecedent of various broad leadership concepts (e.g., transformational, authentic, stewardship, spiritual, servant, to name a few). A sound leader credibility definition may enable the replication of prior leader credibility research.

Research questions regarding leader credibility outcomes include the following:

-

Is leader credibility a necessary antecedent for various leadership theories (e.g., transformational, authentic, etc.)?

-

What are follower-related leader credibility outcomes?

-

What are group-related leader credibility outcomes?

-

What are organizational leader credibility outcomes?

-

Is leader credibility necessary for effective leadership?

-

Are there negative impacts from having high leader credibility?

5 Conclusion

Media and academic research use the term “leader credibility” as if a universal understanding exists. However, our SLR has demonstrated that this is not the case. The current state of the research is murky and lacks a firm theoretical foundation. There cannot be effective sensemaking (Weick et al. 2005) in management or leadership knowledge if a construct lacks a consistent definition and valid measures.

Leader credibility research appears, at best, to be scattered in its measurement approach and, at worst, potentially invalid in its conclusions. If the construct of leader credibility has not been defined and measured sufficiently, studies purporting that leader credibility is impacted by a factor, or that leader credibility causes a particular outcome may lack sufficient construct validity.

Our SLR revealed numerous studies applying inconsistent definitions and measures, but they suggested essential relationships between leader credibility and other factors. In other words, we expose an ironic, significant research weakness: the research on leader credibility lacks credibility. Namely, (1) leader credibility is not consistently defined, and (2) leader credibility is not consistently measured. However, ironically, a consistent definition and measures, leader credibility research is broad and deep. By identifying these gaps in definition, theory, and measure development and providing an accounting of leader credibility knowledge to date, we open the door to a research path forward re-grounding leader credibility, which is similar to the calls in authentic leadership research (Gardner et al. 2021). We hope this work facilitates further exploration of leader credibility and its re-development following sound theory and construct development principles.

Notes

We cite just a few articles for each field.

Our SLR included two Kouzes and Posner peer-review published articles. However, most researchers cite Kouzes and Posner books as a theoretical basis for the construct.

References

Abadir S (2020) The two roles leaders must play in a crisis. Cambridge: Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA. Retrieved from https://ezproxy.mtsu.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/blogs-podcasts-websites/two-roles-leaders-must-play-crisis/docview/2444668446/se-2?accountid=4886

Abu-Tineh AM, Khasawneh SA, Al-Omari A (2008) Kouzes and Posner’s transformational leadership model in practice. Leadersh Org Dev J 29(8):648–660

Alaimo K (2018) Mark zuckerberg has lost all credibility with congress–and the rest of us. (2018). CNN.com. Retrieved from https://www.cnn.com/2018/12/21/opinions/mark-zuckerberg-misled-congress-privacy-nyt-alaimo/index.html

Allahverdyan AE, Galstyan A (2016) Emergence of leadership in communication. PloS one 11(8):e0159301

Amos B, Klimoski RJ (2014) Courage: making teamwork work well. Group Org Manag 39(1):110–128

Andersen K (1961) Quoted in Giffin K (1967) The contribution of studies of source credibility to a theory of interpersonal trust in the communication process. Psychol Bull 68(2):104–120

Avolio BJ, Locke EE (2002) Contrasting different philosophies of leader motivation: altruism versus egoism. Leadersh Q 13(2):169–191

Awaliyah M, Setiawan T (2019) Hoegeng Iman Santoso: Credibility and honesty of the old order leaders until the new order. In: international conference on interdisciplinary language, literature and education (ICILLE 2018):210–213

Balcerzyk D (2020) Trust as a leadership determinant. Eur Res Stud J, Spec Issue 3:486–497

Balwant PT (2016) Transformational instructor-leadership in higher education teaching: a meta-analytic review and research agenda. J Leadersh Stud 9(4):20–42

Basford TE, Offermann LR, Behrend TS (2014) Please accept my sincerest apologies: examining follower reactions to leader apology. J Bus Ethics 119(1):99–117

Bass BM (1990) Bass & Stogdill’s handbook of leadership: Theory, research. & managerial applications (3rd ed.). The Free Press, New York

Bass BM, Bass R (2008) The Bass Handbook of Leadership: Theory, Research, and Managerial Applications, 4th edn. Free Press, New York, NY

Bass BM, Steidlmeier P (1999) Ethics, character, and authentic transformational leadership behavior. Leadersh Q 10(2):181–217

Baumgartner E (2009) Leading the church into world mission: the life and leadership of John Nevins Andrews. J Appl Christ Leadersh 3(1):10–27

Beam A, Claxton RL, Smith SJ (2016) Challenges for novice school leaders: Facing today’s issues in school administration. Educ Leadersh Adm 27:145–162

Berlo DK, Lemert JB, Mertz RJ (1969) Dimensions for evaluating the acceptability of message sources. Public Opin Q 33(4):563–576

Bhindi N, Duignan P (1997) Leadership for a new century: Authenticity, intentionality, spirituality and sensibility. Educ Manag Adm 25(2):117–132

Birkenmeier B, Carson PP, Carson KD (2003) The father of Europe: an analysis of the supranational servant leadership of jean monnet. Int J Organ Theory Behav 6(3):374–400

Blake RR, Mouton JS (1985) The Managerial Grid III. Gulf, Houston, TX

Blanchard K, Zigarmi D, Nelson R (1993) Situational Leadership after 25. Years: a retrospective. J Leadersh Stud 1(1):22–36

Bolkan S, Goodboy AK (2009) Transformational leadership in the classroom: fostering student learning, student participation, and teacher credibility. J Instr Psychol 36(4):296–306

Boone LW, Peborde MS (2008) Developing leadership skills in college and early career positions. Rev Bus 28(3):3–13

Boyce LA, Jackson RJ, Neal LJ (2010) Building successful leadership coaching relationships: examining impact of matching criteria in a leadership coaching program. J Manag Dev 29(10):914–931

Bradley-Levine J (2011) Using case study to examine teacher leader development. J Ethnograph Qual Res 5(4):246–267

Brereton P, Kitchenham BA, Budgen D, Turner M, Khalil M (2007) Lessons from applying the systematic literature review process within the software engineering domain. J Syst Softw 80(4):571–583

Bridgeforth BW (2005) Advancing the practice of leadership: a curriculum. J Leadersh Educ 4(1):4–30

Briner RB, & Denyer D (2012) Systematic review and evidence synthesis as a practice and scholarship tool. In D. M. Rousseau (Ed.), Oxford Handbook of evidence-based management: Companies, classrooms and research, Oxford University Press, Oxford, England, UK. pp. 112e129

Campbell D (1993) Good leaders are credible leaders. Res Technol Manag 36(5):29–31

Cardno C (2014) The functions, attributes and challenges of academic leadership in New Zealand polytechnics. Int J Educ Manag 28(4):352–364

Carrillo RA (2002) Safety leadership formula: Trust+ credibility x competence = results. Prof Saf 47(3):41–47

Chaffee MW, Mills MEC (2001) Navy medicine: a health care leadership blueprint for the future. Mil Med 166(3):240–247

Chaker NN, Walker D, Nowlin EL, Anaza NA (2019) When and how does sales manager physical attractiveness impact credibility: a test of two competing hypotheses. J Bus Res 105:98–108

Chng DHM, Kim TY, Gilbreath B, Andersson L (2018) Why people believe in their leaders-or not. MIT Sloan Manag Rev 60(1):65–70

Chun JU, Choi BK, Moon HK (2014) Subordinates’ feedback-seeking behavior in supervisory relationships: a moderated mediation model of supervisor, subordinate, and dyadic characteristics. J Manag Organ 20(4):463–484

Cichy RE, Schmidgall RS (1996) Leadership qualities of financial executives: in the US lodging industry. Cornell Hotel Restaur Adm Q 37(2):56–62

Cichy RF, Sciarini MP, Patton ME (1992) Food-service leadership: Could Attila run a restaurant? Cornell Hotel Restaur Adm Q 33(1):46–55

Cichy RF, Aoki TT, Patton ME, Hwang KY (1993) Shidō-sei: Leadership in Japan’s commercial food-service industry. Cornell Hotel Restaur Adm Q 34(1):88–95

Clark WR, Clark LA, Raffo DM, Williams RI Jr (2021) Extending fisch and block’s (2018) tips for a systematic review in management and business literature. Manag Rev Q 71(1):215–231

Clampitt PG (1991) Communicating for managerial effectiveness. Sage Publications, Newbury Park, CA

Cooper CD, Scandura TA, Schriesheim CA (2005) Looking forward but learning from our past: potential challenges to developing authentic leadership theory and authentic leaders. Leadersh Q 16(3):475–493

Cope J, Kempster S, Parry K (2011) Exploring distributed leadership in the small business context. Int J Manag Rev 13(3):270–285

Davidhizar R (2007) Does having a “brand” help you lead others? Health News 26(2):159–163

de Guzman AB, Ormita MJM, Palad CMC, Panganiban JK, Pestaño HO, Pristin MWP (2007) Filipino nursing students’ views of their clinical instructors’ credibility. Nurse Educ Today 27(6):529–533

Denis JL, Langley A, Cazale L, Denis JL, Cazale L, Langley A (1996) Leadership and strategic change under ambiguity. Organ Stud 17(4):673–699

Dull M (2009) Results-model reform leadership: Questions of credible commitment. J Pub Adm Res Theory 19(2):255–284

Einwohner RL (2007) Leadership, authority, and collective action: jewish resistance in the ghettos of Warsaw and Vilna. Am Behav Sci 50(10):1306–1326

Farling ML, Stone AG, Winston BE (1999) Servant leadership: setting the stage for empirical research. J Leadersh Stud 6(1–2):49–72

Fedor DB, Rensvold RB, Adams SM (1992) An investigation of factors expected to affect feedback seeking: a longitudinal field study. Pers Psychol 45(4):779–805

Fernandez RM (1991) Structural bases of leadership in intraorganizational networks. Soc Psychol Q 54(1):36–53

Fisch C, Block J (2018) Six tips for your (systematic) literature review in business and management research. Manag Rev Q 68(2):103–106

Fjałkowski K (2014) Politicians and social leaders. Introducing a model of mutual relations and shaping beliefs of voters. Ekonomia i Prawo. Econ Law 13(3):359–375

Flanagin AJ, Metzger MJ (2000) Perceptions of Internet information credibility. J Mass Commun Q 77(3):515–540

Fleming C (2015) Volkswagen diesel scandal threatens to ruin its credibility and value. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved from https://www.latimes.com/business/autos/la-fi-hy-vw-diesel-20150923-story.html

Frost JK, Edwards R (2018) It’ll be okay, because we belong together: the influence of person-organization fit on interpretation of bad-news messages in academic settings. Commun Stud 69(5):499–521

Gabris GT (2003) Developing public managers into credible public leaders: theory and practical implications. Int J Org Theory Behav 7(2):209–230

Gabris GT, Ihrke DM (1996) Burnout in a large federal agency: phase model implications for how employees perceive leadership credibility. Pub Adm Q 20(2):220–249

Gabris GT, Ihrke DM (2000) Improving employee acceptance toward performance appraisal and merit pay systems: the role of leadership credibility. Rev Pub Pers Adm 20(1):41–53

Gabris GT, Ihrke DM (2003) Unanticipated failures of well-intentioned reforms: some lessons from federal and local governments. Int J Org Theory Behav 6(2):195–225

Gabris GT, Ihrke DM (2007) No end to hierarchy: Does rank make a difference in perceptions of leadership credibility? Adm& Soc 39(1):107–123

Gabris GT, Mitchell K (1991) The everyday organization: a diagnostic model for assessing adaptation cycles. Pub Adm Q 14(4):498–518

Gabris GT, Grenell K, Ihrke DM, Kaatz J (1999) Managerial innovation as affected by administrative leadership and policy boards. Pub Adm Q 23(2):223–249

Gabris GT, Grenell K, Ihrke DM, Kaatz J (2000) Managerial innovation at the local level: some effects of administrative leadership and governing board behavior. Pub Product Manag Rev 23(4):486–494

Gabris GT, Golembiewski RT, Ihrke DM (2001) Leadership credibility, board relations, and administrative innovation at the local government level. J Pub Adm Res Theory 11(1):89–108

Gale JJ, Bishop PA (2014) The work of effective middle grades principals: responsiveness and relationship. RMLE Online 37(9):1–23

Gardner WL, Avolio BJ, Luthans F, May DR, Walumbwa F (2005) “Can you see the real me?” A self-based model of authentic leader and follower development. Leadersh Q 16(3):343–372

Gardner WL, Karam EP, Alvesson M, Einola K (2021) Authentic leadership theory: the case for and against. Leadersh Q 32(6):101495

Garst BA, Weston KL, Bowers EP, Quinn WH (2019) Fostering youth leader credibility: professional, organizational, and community impacts associated with completion of an online master’s degree in youth development leadership. Child Youth Serv Rev 96:1–9

Goldsmith RE, Lafferty BA, Newell SJ (2000) The impact of corporate credibility and celebrity credibility on consumer reaction to advertisements and brands. J Advert 29(3):43–54

Grasse NJ, Heidbreder B, Ihrke DM (2014) City managers’ leadership credibility: explaining the variations of self-other assessments. Pub Adm Q 38(4):544–572

Grint K, Hol C, Neyroud P (2017) Cultural change and lodestones in the British police. Int J Emerg Serv 6(3):166–176

Haake U, Rantatalo O, Lindberg O (2017) Police leaders make poor change agents: leadership practice in the face of a major organizational reform. Polic Soc 27(7):764–778

Hackman MZ, Johnson CE (1996) Leadership, a communication perspective. Waveland Press, Prospect Heights, IL

Hair JF, Black WC, Babin BJ, Anderson RE, Tatham RL (2010) Multivariate Data Analysis. Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ

Harshman EF, Harshman CL (1999) Communicating with employees: building on an ethical foundation. J Bus Ethics 19(1):3–19

Hass RG (1981) Effects of source characteristics on cognitive responses and persuasion. In: RE Petty, TM Ostrom, TC Brock (Eds.), Cognitive responses in persuasion. Lawrence Erlbaum, Hillsdale, NJ, pp 141–172

Hati SRH, Idris A (2019) The role of leader vs organisational credibility in Islamic social enterprise marketing communication. J Islam Mark 10(4):1128–1150

Hershey DA, Farrell AH (1997) Perceptions of wisdom associated with selected occupations and personality characteristics. Curr Psychol 16(2):115–130

Hinkin TR (1995) A review of scale development practices in the study of organizations. J Manag 21(5):967–988

Hofstede G (2001) Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions and organizations across nations. Sage Publications

Holland WR (1997) The high school principal and barriers to change: the need for principal credibility. NASSP Bull 81(585):94–98

Holmes WT (2016) Motivating language theory: antecedent variables–critical to both the success of leaders and organizations. Dev Learn Org: Int J 30(3):13–16

Holmes WT, Parker MA (2017) Communication: empirically testing behavioral integrity and credibility as antecedents for the effective implementation of motivating language. Int J Bus Commun 54(1):70–82

Holt S, Bjorklund R, Green V (2009) Leadership and culture: examining the relationship between cultural background and leadership perceptions. J Glob Bus Issues 3(2):149–164

Hovland CI, Janis IL, Kelley HH (1953) Communication and persuasion. Yale University Press, New Haven, CT

Huffaker D (2010) Dimensions of leadership and social influence in online communities. Hum Commun Res 36(4):593–617

Iko Afe CE, Abodohoui A, Mebounou T, Karuranga E (2019) Perceived organizational climate and whistleblowing intention in academic organizations: evidence from Selçuk University (Turkey). Eurasian Bus Rev 9(3):299–318

Irawanto DW, Ramsey PL, Tweed DM (2013) The paternalistic relationship: authenticity and credibility as a source of healthy relationships. J Values-Based Leadersh 6(1):1–11

Iszatt-White M, Kempster S (2019) Authentic leadership: Getting back to the roots of the ‘root construct’? Int J Manag Rev 21(3):356–369

Jones R, Kriflik G (2005) Strategies for managerial self-change in a cleaned-up bureaucracy: a qualitative study. J Manag Psychol 20(5):397–416

Kapasi I, Sang KJ, Sitko R (2016) Gender, authentic leadership and identity: analysis of women leaders’ autobiographies. Gend Manag: Int J 31(5/6):339–358

Kaufmann G, Drevland GC, Wessel E, Overskeid G, Magnussen S (2003) The importance of being earnest: displayed emotions and witness credibility. Appl Cognit Psychol: Off J Soc Appl Res Memory Cognit 17(1):21–34

Kelley HH, Thibaut JW (1978) Interpersonal relations: A theory of interdependence. Wiley, New York

Kerns CD (2017) Providing direction: a key managerial leadership practice. J Appl Bus Econmics 19(9):25–41

Kim TY, Bateman TS, Gilbreath B, Andersson LM (2009) Top management credibility and employee cynicism: a comprehensive model. Human Relat 62(10):1435–1458

Komai M, Stegeman M (2010) Leadership based on asymmetric information. Rand J Econ 41(1):35–63

Kouzes JM, Posner BZ (2005) Leading in cynical times. J Manag Inq 14(4):357–364

Kouzes JM, Posne, BZ (1992) The credibility factor: What people expect of leaders. In: Taylor RL, Rosenbach WE (Eds.), Military leadership: In pursuit of excellence. Westview, Boulder, CO, pp 133–138

Kouzes JM, Posner BZ (2011) Credibility: How leaders gain and lose it, why people demand it. Wiley, San Francisco, CA

Kouzes JM, Posner BZ (2012) The leadership challenge: how to make extraordinary things happen in organizations. Wiley, San Francisco

Lafferty L (2004) Leadership in trial advocacy: credibility is a cornerstone of effective trial advocacy. Am J Trial Advoc 28:517–530

Landis EA, Hill D, Harvey MR (2014) A synthesis of leadership theories and styles. J Manag Policy Pract 15(2):97–100

Lee GJ (2011) Mirror, mirror: preferred leadership characteristics of South African managers. Int J Manpow 32(2):211–232

Lissauer M (2005) Honest leadership inspires credibility. Prweek, 8, 8. Retrieved from https://ezproxy.mtsu.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/magazines/honest-leadership-inspires-credibility/docview/232046445/se-2?accountid=4886

Loh E, Morris J, Thomas L, Bismark MM, Phelps G, Dickinson H (2016) Shining the light on the dark side of medical leadership–a qualitative study in Australia. Leadersh Health Serv 29(3):313–330

MacKenzie SB, Podsakoff PM, Podsakoff NP (2011) Construct measurement and validation procedures in MIS and behavioral research: Integrating new and existing techniques. MIS Q 35(2):293–334

McAllister DJ (1995) Affect-and cognition-based trust as foundations for interpersonal cooperation in organizations. Acad Manag J 38(1):24–59

McCauley CD, Palus CJ (2021) Developing the theory and practice of leadership development: a relational view. Leadersh Q 35(2):1–15

McCroskey JC, Teven JJ (1999) Goodwill: a reexamination of the construct and its measurement. Commun Monogr 66(1):90–103

McCroskey JC, Young TJ (1981) Ethos and credibility: the construct and its measurement after three decades. Cent States Speech J 32:24–34

Men LR (2012) CEO credibility, perceived organizational reputation, and employee engagement. Pub Relat Rev 38(1):171–173

Meyers MD (2013) Qualitative Research in Business & Management. Sage, Los Angeles

Miller S (2020) The Secret to Germany’s COVID-19 Success: Angela Merkel is a Scientist, The Atlantic, https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2020/04/angela-merkel-germany-coronavirus-pandemic/610225/

Munn Z, Peters MD, Stern C, Tufanaru C, McArthur A, Aromataris E (2018) Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol 18(1):1–7

Murphy S (2016) 10 benefits of being a trustworthy leader. Inc. https://www.inc.com/shawn-murphy/10-benefits-of-being-a-trustworthy-leader.html

Mussig DJ (2003) A research and skills training framework for values-driven leadership. J Eur Ind Train 27(2–4):73–79

Myerson RB (2008) The autocrat’s credibility problem and foundations of the constitutional state. Am Polit Sci Rev 102(1):125–139

Myers SA, Martin MM (2015) Understanding the source: Teacher credibility and aggressive communication traits. In: Mottel TP, Richmond VP, McCroskey JC (eds) Handbook of instructional communication: Rhetorical and relational perspectives. Routledge, New York, NY, pp 67–88

Newman A, Kiazad K, Miao Q, Cooper B (2014) Examining the cognitive and affective trust-based mechanisms underlying the relationship between ethical leadership and organizational citizenship: A case of the head leading the heart? J Bus Ethics 123(1):113–123

Nixon S (2011) Merkel and sarkozy have lost credibility, The Wall Street Journal, https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052970204554204577022222367756042

Northfield S (2014) Multi-dimensional trust: how beginning principals build trust with their staff during leader succession. Int J Leadersh Educ 17(4):410–441

Norton WI Jr, Murfield MLU, Baucus MS (2014) Leader emergence: the development of a theoretical framework. Leadersh Org Dev J 35(6):513–529

O’Keefe DJ (1990) Persuasion: theory and research. Sage Publications Inc., Thousand Oaks, California

Ohanian R (1990) Construction and validation of a scale to measure celebrity endorsers’ perceived expertise, trustworthiness, and attractiveness. J Advert 19(3):39–52

Paton R, Goel A (1993) Managing the impossible: how district managers are effective in India. Int J Pub Sect Manag 6(1):16–29

Patterson BJ, Krouse AM (2015) Competencies for leaders in nursing education. Nurs Educ Perspect 36(2):76–82

Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Bachrach DG, Podsakoff NP (2005) The influence of management journals in the 1980s and 1990s. Strateg Manag J 26(5):473–488

Politis JD (2005) The influence of managerial power and credibility on knowledge acquisition attributes. Leadersh Org Dev J 26(3):197–214

Posner BZ, Kouzes JM (1988) Development and validation of the Leadership Practices Inventory. Educ Psychol Measur 48:483–496

Posner BZ, Kouzes JM (1988) Relating leadership and credibility. Psychol Rep 63(2):527–530

Pulles DC, Montes FJL, Gutierrez-Gutierrrez L (2017) Network ties and transactive memory systems: leadership as an enabler. Leadersh Org Dev J 38(1):56–73

Raffo D, Williams R (2018) Evaluating potential transformational leaders: weighing charisma vs. credibility. Strategy Leadersh 46(6):1–11

Rego A, Pina e Cunha M (2012) They need to be different, they feel happier in authentizotic climates. J Happiness Stud 13(4):701–727. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-011-9287-1

Ritter BA, Hedberg PR, Gower K (2016) Enhancing teacher credibility: What we can learn from the justice and leadership literature. Org Manag J 13(2):90–100

Rojon C, Okupe A, McDowall A (2021) Utilization and development of systematic reviews in management research: What do we know and where do we go from here? Int J Manag Rev 23(2):191–223

Rusaw AC (1996) Achieving credibility: an analysis of women’s experience. Rev Pub Personnel Adm 16(1):19–30

Russell RF (2001) The role of values in servant leadership. Leadersh Org Dev J 22(2):76–84

Russell RF, Stone AG (2002) A review of servant leadership attributes: developing a practical model. Leadersh Org Dev J 23(3):145–157

Ryan J, Tuters S (2017) Picking a hill to die on: discreet activism, leadership and social justice in education. J Educ Adm 55(5):569–588

Salicru S, Chelliah J (2014) Messing with corporate heads? Psychological contracts and leadership integrity. J Bus Strateg 35(3):38–46

Scarnati JT (1997) Beyond technical competence: honesty and integrity. Career Dev Int 2(1):24–27

Schraeder M, Jordan MH, Self DR, Hoover DJ (2016) Unlearning cynicism: a supplemental approach in addressing a serious organizational malady. Int J Organ Anal 24(3):532–547

Schutte N, Barkhuizen N (2016) The reciprocal relationship between human resource management professionalism and a diverse South African workplace context. J Appl Bus Res 32(2):493–506

Siddaway AP, Wood AM, Hedges LV (2019) How to do a systematic review: a best practice guide for conducting and reporting narrative reviews, meta-analyses, and meta-syntheses. Annu Rev Psychol 70:747–770

Simons TL (1999) Behavioral integrity as a critical ingredient for transformational leadership. J Organ Chang Manag 12(2):89–104

Simons HW, Berkowitz NN, Moyer RJ (1970) Similarity, credibility, and attitude change: a review and a theory. Psychol Bull 73(1):1–16

Sinha S (2020) Leadership credibility–Why it matters & How to develop it. Soaring Eagles. https://soaringeagles.co/resources/leadership-credibility-why-it-matters-how-to-develop-it/