Abstract

This paper explores the psychological motivations behind collectivist behavior in Japan and the U.S. Using data from a large-scale questionnaire survey, we examine the causes of collectivist behavior (i.e., group conformity) at workplaces and at home. Our key findings are as follows: (i) in Japan, people conform to their groups, both at work and at home, because they consider that cooperation with others will result in greater achievement; (ii) in both Japan and the U.S., people conform to their groups, both at work and at home, because behaving similarly to others makes them feel comfortable; and (iii) in both Japan and the U.S., people conform to their family’s opinion at home because they value cooperation with family members. Our findings suggest that institutional differences between Japan and the U.S. give rise to the differences in psychological motivations for collectivist behavior.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

For the past two decades, economics has drawn attention to the role of culture in understanding economic phenomena. Culture is defined as “those customary beliefs and values that ethnic, religious, and social groups transmit fairly unchanged from generation to generation” (Guiso et al. 2006). Culture not only shapes people’s preferences and expectations, but also influences law and political institutions in society, and therefore it significantly affects economic behavior and outcomes (Aoki 2010; Guiso et al. 2003, 2006; Tabellini 2008; Williamson 2000; Zingales 2015).

While there are several dimensions that describe the elements of culture, individualism-collectivism (IC) is one of the most important dimensions characterizing the values of a particular society, as well as the beliefs and behavior of its people. A society’s degree of IC varies depending on factors such as affluence, geographical environment, social mobility, and cultural complexity (Hofstede 1980). For instance, Brazil, India, Russia, and Japan are collectivist countries, whereas France, the U.S., England, and Germany are individualist countries, though to varying degrees (Gelfand et al. 2004; Triandis 1995).Footnote 1

IC also varies widely within countries (Hofstede 1980; Triandis 2001; Triandis et al. 1993). In other words, there are individualist people in collectivist countries and vice versa. Comparing individuals in the U.S. and Japan, within-country variation in IC is substantially greater than between-country variation (Matsumoto et al. 1996). Personal individualist or collectivist tendency typically reflects traits such as age, social class, education, occupation, and sex (Triandis 1995). However, based on previous studies in economics and social psychology, we argue that individuals’ internal or psychological factors (e.g., mentality, cognition patterns, beliefs, and emotions) would predict individual IC behavior, and investigation of the relationship between these psychological factors and IC could be a key to understanding why IC emerges. For example, people who believe that cooperation promotes or inhibits outcomes can be more or less collectivist, respectively.

We propose that the psychological motivations for collectivist behavior would differ among countries. This should depend not only on each country’s formal institutions such as laws but also on its informal institutions such as customs, traditions, and peoples’ beliefs (Greif 2006; North 1991; Williamson 2000). For example, in countries where people believe that intra-group cooperation will result in better outcomes, collectivist behavior would arise with the expectation that better economic outcomes can be achieved through cooperation in a group. Conversely, in countries where people do not believe in the efficiency of group cooperation, collectivist behavior could arise due to different psychological motivations, such as feeling comfortable when behaving similarly to others.

In this paper, we analyze data from a large-scale questionnaire conducted in Japan and the U.S. to examine the associations of various psychological factors with collectivist behavior. In doing so, we examine individuals’ motivations for collectivist behavior and compare them between the two countries.

Following earlier research, we operationalize individual IC as individuals’ self-reported group conformity (Bond and Smith 1996; Schimmack et al. 2005; Takano and Osaka 1999).Footnote 2 Respondents rated their degree of following group opinion in their workplace and family, respectively, on a 5-point Likert scale. Responses are considered to indicate two factors: workplace conformity (W-CONF) and family conformity (F-CONF). Additionally, we examine the following psychological factors affecting conformity: the efficiency factor (EFFICIENCY) refers to the individual’s belief that cooperation in a group promotes achievement, the comfort factor (COMFORT) indicates comfort felt when behaving similarly to others, and the satisfaction factor (SATISFACTION) denotes satisfaction felt when cooperating with others. We then examine associations of W-CONF and F-CONF with EFFICIENCY, COMFORT, and SATISFACTION to examine individual motivations for group conformity.Footnote 3

We expect the motivations for conformist behavior to differ between Japanese and U.S. individuals, because the two countries have had different social histories and environments that shaped different institutions. We therefore analyze the Japanese and U.S. data separately. More concretely, we conduct regression analysis for each of Japan and the U.S. in terms of whether and how the above three psychological factors are associated with conformity behavior; thus, we compare differences in individuals’ motivation for conformity between those two countries.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 discusses psychological motivations for conformity behavior and institutional differences between Japan and the U.S. Section 3 describes our data and methods. Section 4 reports empirical results. Section 5 discusses the results and their implications. Section 6 concludes.

2 Psychological motivations and Japan–U.S. institutional differences

2.1 Psychological motivations for conformity

People have several motives to conform to their groups. Following the previous literature on social psychology and economics, we consider three psychological factors motivating conformity: (a) the efficiency factor, (b) the comfort factor, and (c) the satisfaction factor.

The efficiency factor refers to the individuals’ belief that cooperation in a group promotes achievement. In human society, it is widely known that cooperative action within a group often yields better economic outcomes than when individuals in a group act independently. This is supported by evidence suggesting that groups that cooperated tended to survive and expanded more than other groups (Bowles and Gintis 2011). If people believe in the efficiency of in-group cooperation, they will cooperate by conforming to the group’s decisions even when their opinions are different.

The comfort factor indicates the comfort that individuals feel when behaving similarly to others. In uncertain events and situations, people are not confident in the accuracy of their own information. Accordingly, following others can lead to safer and better decisions (Griskevicius et al. 2006). Thus, people often feel more comfortable when following group judgments based on the information of various members in the group (Castelli et al. 2001; Quinn and Schlenker 2002).

The satisfaction factor corresponds to satisfaction individuals feel when cooperating with others. Some people conform to groups in order to gain approval and affiliation and increase the likelihood that they will be liked by others (Castelli et al. 2001; Cialdini et al. 1999; Renkema et al. 2008). In addition, some people obtain psychological satisfaction from going along with others because they may gain “identity utility” when their behavior is consistent with the group’s code of conduct (Akerlof and Kranton 2010). Others try to avoid conflict by emphasizing harmony within the group; that is, they tend to suppress their own opinions and conform to the opinions of the group (Yamaguchi 1994).

2.2 Institutional differences between Japan and the U.S.

Previous studies in economics, social psychology, and political science have shown that institutions in each country significantly affect human behavior and outcomes (Greif 2006; North 1991; Williamson 2000). North (1991) states that “institutions are the humanly devised constraints that structure economic and political interaction. They consist of both informal constraints (sanctions, taboos, customs, traditions, and codes of conduct), and formal rules (constitutions, laws, property rights)” (p. 97). There are differences between Japan and the U.S. not only in formal rules such as laws but also in informal institutions such as customs, traditions, and norms (Hofstede 1980; La Porta et al. 2008). These institutional differences would give rise to differences in psychological motivations for conformity between the two countries. In particular, we conjecture that differences in informal institutions between Japan and the U.S. will lead to a difference in the impact of the efficiency factor on people’s conformity.

In Japan, given its historical practices, the belief in achieving better economic outcomes through intra-group cooperation is likely to motivate people’s conformity. First, Japan's high population density, coupled with its limited natural resources, may have forced people to cooperate as it seemed more efficient for survival (Matsumoto et al. 1996). Second, in the past, most Japanese individuals secured their livelihood through agricultural activities that require cooperation (Triandis et al. 1993). In particular, they were engaged in rice farming, which requires irrigation systems and an extraordinary amount of labor, making cooperation more valuable (Talheim et al. 2014).Footnote 4 Reflecting this history, Japanese elementary education has encouraged pupils to study in groups and teaches the restraint of the ego (Vogel 1979). These historical and educational traditions can inculcate belief in the economic value of cooperation and conformity among the Japanese people.

Furthermore, Japan was a country with low mobility of people, which may also have contributed to the efficiency of in-group cooperation.Footnote 5 As is well known from game theory, long-term interactions among the same members promote greater gains through cooperation (Fudenberg and Levine 2009). Individuals will not pursue self-interest for the benefit of the group as long as they expect rewards from the group in the long-run or punishment by other group members (Greif 1994; Yamaguchi 1994). This may also have fostered the belief that cooperation promotes achievement, implying that as belief in the economic efficiency of in-group cooperation becomes stronger, people will behave in a more collectivist manner. Therefore, we conjecture that the efficiency factor will predict Japanese conformity behavior.

In contrast, the U.S. is characterized by abundant resources and a vast land area. In such an environment, the need to cooperate for economic gain is relatively small. Therefore, Americans are taught to cultivate independence rather than cooperation (Matusmoto et al. 1996). Moreover, the U.S. has been well known as a country with many immigrants and high mobility of people (Campbell and Kean 2012). In highly mobile societies, relationships and interactions among people tend to be shorter-term than in low-mobility societies. Game theory has accurately predicted that individuals in short-term interactions with others may experience failures of coordination and socially inefficient outcomes (Bowles and Gintis 2011). Therefore, in the U.S., even if a person recognizes that in-group cooperation efficiently achieves better outcomes, he or she may behave individualistically due to a perceived risk of exploitation by others. This suggests that the efficiency factor is less likely to predict conformity behavior in the U.S. compared with Japan.

We will examine the three psychological factors that can lead to conformity in Japan and the U.S., and thereby attempt to provide an insight into whether and how institutional differences between the two countries influence the effects of these factors.

3 Method

3.1 Basic data

This study used data collected in Japan and the U.S. during February 2006 in a panel survey conducted by the Center of Excellence (COE) project at Osaka University. The survey gathered data suitable for the analysis of human behavior and preferences in both countries, and particularly examined respondents’ preferences (e.g., time discounting, risk aversion, personal values). The questionnaire contained 87 questions, some of which included sub-questions, and the same questions were asked in both countries. Questions were initially composed in Japanese and then translated into English by a Japanese person who had stayed in the U.S. from ages 10 to 18 years. The translation was conducted with assistance from a specialist at a U.S. survey company. Finally, a prominent bilingual Japanese American economist assessed the semantic identities of the Japanese and English surveys. The survey was conducted annually from 2003 in Japan and from 2005 in the U.S., until 2013. However, five questions concerning IC were included in only the 2006 and 2012 waves of the survey.

This paper analyzed data collected in the 2006 survey from the five questions concerning IC.Footnote 6 In Japan, 4879 people aged 20–75 years nationwide were selected using double stratified random sampling. Respondents were visited at their homes and handed the questionnaire. Completed questionnaires were collected several days later; 3763 questionnaires were returned (response rate: 77.1%). In the U.S., 4868 people aged 15–99 years were randomly selected from the registered membership of a large survey company, which covered all U.S. states, except Alaska and Hawaii. Questionnaires were distributed by mail; 3120 were returned (response rate: 64.1%).

3.2 Measurement of conformity

We assume that individuals’ group conformity predicts their tendency to follow group decisions in their workplace and at home. Thus, we assume the following factors of conformity: (i) workplace conformity (W-CONF; i.e., the individual’s tendency to follow group decisions in the workplace), and (ii) home conformity (F-CONF; i.e., the individual’s tendency to follow family decisions at home). In our survey, respondents rated their conformity on these factors by responding to the following questions: “At work, I should follow opinion as a group” and “At home, I should follow my family’s opinion.” Responses to all questionnaire items used a 5-point Likert scale (1 = it doesn't hold true at all for me; 5 = it is particularly true for me). Therefore, higher scores indicate greater conformity on each factor.

3.3 Psychological factors

As discussed above, we assume that individual conformity behavior stems from three psychological factors, namely, the efficiency factor, the comfort factor, and the satisfaction factor. First, we measure respondents’ prioritization of the efficient factor (EFFICIENCY) using the item “Working as a group results in greater achievement than working individually.” Higher scores on EFFICIENCY indicate a stronger belief that cooperation more efficiently promotes outcomes. Second, we measure respondents’ prioritization of the comfort factor (COMFORT) using the item “Behaving similarly to people around me makes me feel comfortable.” Higher scores on COMFORT indicate more comfort from behaving similarly to other group members. Third, we measure respondents’ prioritization of the satisfaction factor (SATISFACTION) using the item “I am more satisfied when I achieve a goal by cooperating with others than by myself.” Thus, higher scores on SATISFACTION indicate greater satisfaction from cooperation itself.

3.4 Regression equations for conformity in the workplace and at home

We analyze the following ordered probit models to estimate respondents’ psychological motivation to conform at work and at home:

In these models, \(i\) represents a respondent from either Japan or the U.S. and \(j\) represents the W-CONF or F-CONF score of 1–5. \({\text{CONTROL}}_{i}\) represents a set of individual attribute variables such as sex, age, family structure, education, occupation, and religion.Footnote 7 Table 1 presents definitions and summary statistics of the variables. In models (1) and (2), underlying scores are estimated as the probability that the linear function of the three psychological factors and individual attributes, plus random error, is within the cutoffs. \(\kappa_{j}\) represents a set of cut-points corresponding to an ordinal value \(j\). \(\varepsilon_{i}\) represents normally distributed random error. We estimate the ordered probit models (1) and (2) separately for the Japanese and U.S. samples, thereby examining the ability of EFFICIENCY, COMFORT, and SATISFACTION to predict W-CONF and F-CONF among Japanese and U.S. respondents, respectively.

4 Results

4.1 Data overview

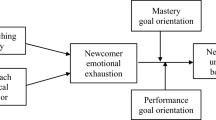

Respondents did not necessarily answer all questions related to the variables we analyzed. We excluded responses without data for these variables. Thus, the final number of responses included in the data analyses was reduced to 2797 in Japan and 2177 in the U.S. Table 1 summarizes statistics for all variables included in our analyses. Table 2 compares the mean values of conformity variables and psychological factors in the Japanese and U.S. samples. Mean W-CONF and F-CONF scores in the Japanese sample were significantly larger than in the U.S. sample, suggesting that Japanese people were generally more motivated to conform to their group than American people (Yamagishi et al. 2008).Footnote 8 Additionally, this inference remained supported after we controlled for differences in response style between the two countries, using a within-culture standardization procedure for each variable (Table 3).Footnote 9 Figure 1 presents response distributions for each conformity variable in the Japanese and U.S. samples, respectively. The distributions of W-CONF and F-CONF were both skewed to the right for Japan, and to the left for the U.S. These results support the view that Japanese people are more collectivist than American people (Hofstede 1980; Triandis 1995).Footnote 10

Conformity variables: W-CONF and F-CONF. Each figure shows the histogram of respondents in Japan and the U.S. The vertical axis indicates the percentage number of respondents, and the horizontal axis indicates the questionnaire choice in which 1= “it doesn't hold true at all for me” and 5= “it is particularly true for me”

Mean differences in scores for psychological factors were also found between the two countries (Table 2). EFFICIENCY and SATISFACTION were significantly higher in Japan than in the U.S. (p < 0.01); however, COMFORT was significantly higher in the U.S. than in Japan (p < 0.01). A comparison of means after within-culture standardization was consistent with these results (Table 3). Additionally, a considerable proportion of U.S. respondents assigned high scores to COMFORT (Fig. 2), although individualism and independence are commonly regarded as representative American values (Matsumoto et al. 1996).

Psychological factors. Each figure shows the histogram of respondents in Japan and the U.S. The vertical axis indicates the percentage number of respondents, and the horizontal axis indicates the questionnaire choice in which 1= “it doesn't hold true at all for me” and 5= “it is particularly true for me”

A large amount of heterogeneity in conformity and psychological factors scores was observed within countries, in addition to differences between the two countries (Figs. 1 and 2); this result allowed us to analyze the motivations of conformist behavior in each country.

4.2 Workplace conformity

Tables 4 and 5 present the estimation results concerning workplace conformity [model (1)] and home conformity [model (2)], respectively.Footnote 11

Table 4 shows the estimation results for the ordered probit regression of W-CONF in the Japanese and U.S. samples. EFFICIENCY had significantly positive estimates in Japan (p < 0.05), but non-significant estimates in the U.S. The magnitude of the coefficient was significantly larger in Japan than in the U.S. (p < 0.05). This result suggests that Japanese people tend to conform in the workplace because they believe that cooperation more effectively promotes productivity, and that economic efficiency is less likely to motivate workplace conformity among Americans.

COMFORT had significantly positive estimates in both Japan and the U.S. (p < 0.05), suggesting that both Japanese and American people tend to conform in the workplace because it makes them feel comfortable. The Wald test revealed that the difference in both coefficients was not significant.

In contrast, non-significant estimates were obtained for SATISFACTION in both Japan and the U.S., suggesting that Japanese and American people do not tend to conform in the workplace because they find it satisfying.

Regarding individual attributes, the estimated coefficient of respondents’ sex was significantly negative in the W-CONF regression in both Japan and the U.S. (p < 0.05). This result suggests that men in both countries are less likely to conform at work than women, supporting earlier research (e.g., Cross et al. 2017; Triandis 1995). Except for management status, the other attributes were not significant for the Japanese sample, while some variables including occupation were significant in the U.S. sample. This last result suggests that degree of conformity in the workplace in the U.S. depends on occupation.

4.3 Home conformity

Table 5 presents the estimation results for the ordered probit regression of F-CONF. The estimated coefficients of EFFICIENCY were significantly positive in Japan (p < 0.05) and non-significant in the U.S. This result suggests that Japanese, but not U.S. individuals tend to conform at home because they believe it more efficiently promotes better outcomes.

The estimated coefficients of COMFORT were significant in both Japan and the U.S. The U.S. coefficient was larger than the Japanese one (p < 0.10), suggesting that COMFORT is an important motivation for home conformity in the U.S. The results suggest that Americans tend to conform at home because it makes them feel comfortable.

The estimated coefficients of SATISFACTION were significantly positive in both Japan and the U.S. (p < 0.05); additionally, the Wald test indicated that the estimated coefficient was significantly larger in the U.S. than in Japan. These results suggest that both Japanese and American people tend to conform at home because they find it more satisfying; additionally, this tendency can be stronger among Americans than among Japanese people.

Regarding individual attributes, sex was significantly positive, suggesting that men in both countries are more likely to conform at home than women are. This is an interesting phenomenon yet to be identified by previous research. Concerning other individual attributes, religion did not affect workplace conformity in the U.S. but affected home conformity. On the other hand, occupation affected workplace conformity but did not affect home conformity. These results suggest that in the U.S. religion is an important element of home conformity, while occupation affects workplace conformity.

Our empirical results are summarized as follows:

-

1.

In Japan, EFFICIENCY predicted conformity both in the workplace and at home, while this was not observed in the U.S.

-

2.

In both the U.S. and Japan, COMFORT predicted conformity both in the workplace and at home,

-

3.

In both the U.S. and Japan, SATISFACTION predicted conformity at home, but not in the workplace.

4.4 Endogeneity

The above estimated coefficients for EFFICIENCY, COMFORT, and SATISFACTION in models (1) and (2) may partly involve an endogeneity problem: conformist behaviors could have caused individuals to hold pro-conformist beliefs, such as “I don’t feel satisfied or comfortable working individually because I have cooperated with others for so long.” Therefore, we employed the control-function instrumental variable estimation (CF) to manage potential reverse causality among the conformity variables and psychological factors.Footnote 12 CF provides consistent estimates for coefficients on endogenous regressors in parametric nonlinear models, including the ordered probit model, while the consistency is not guaranteed in two-stage predictor substitution, the usual IV method, for nonlinear models (Terza et al. 2008; Vella 1993; Wooldridge 2014, 2015). Thus, we used CF to estimate the two ordered probit models with the instrumental variables. In the first stage of estimation of CF, auxiliary regressions for endogenous regressors were conducted using instrumental variables the same as in the usual IV method. The second-stage regressions were subsequently performed by including the first-stage generalized residuals in the outcome equation of interest, that is, Eqs. (1) and (2).Footnote 13 In CF, the significance of the first-stage residuals in the second-stage regression indicates the endogeneity of the regressors.

Tables 6 and 7 present the CF estimated coefficients for models (1) and (2). We adopted the individual attributes that were not significant in Tables 4 and 5 as the instrumental variables in the first-stage regressions and those that were significant as the control variables in the second-stage regressions.Footnote 14 In these tables, \(e^{{{\text{EFFICIENCY}}}}\), \(e^{{{\text{COMFORT}}}}\), and \(e^{{{\text{SATISFACTION}}}}\) indicate residuals for EFFICIENCY, COMFORT, and SATISFACTION in the first-stage regression.

In Tables 6 and 7, no residuals of the first-stage regression are significant, suggesting that the three psychological variables were exogenous in all cases. As per the orthogonality conditions, Sargan’s J-test statistics reported at the bottom of Tables 6 and 7 could not reject the validity of our instruments. As for the weak-instruments problem, conventional tests in linear instrumental variable regression, such as the test of Stock and Yogo (2005) were not applicable to our non-linear regressions. Still, we confirmed that one or more instruments were significant at the 1% level in the first-stage regression for EFFICIENCY, COMFORT, and SATISFACTION, suggesting that the weak instruments problem was not serious in our case if it was present.

Accordingly, the estimates of psychological variables were qualitatively the same as those in Tables 4 and 5, except that COMFORT became non-significant in the F-CONF regression for the Japanese sample. Thus, the endogeneity problem was not serious in the estimation of Eqs. (1) and (2).

4.5 Other robustness checks

Persons without a regular occupation (resp., without a family) may not provide meaningful responses to the workplace (resp., home) conformity questions. Therefore, as an additional robustness check, we conducted a subsample regression of W-CONF by excluding respondents with no regular occupation, and a subsample regression of F-CONF by excluding single respondents.Footnote 15 However, we found that the estimation results did not change substantially in the sub-sample regressions.Footnote 16

We also used the ordered logit model instead of the ordered probit models; the estimation results on the three psychological factors remained qualitatively unchanged. Additionally, the estimation results remained qualitatively unchanged in the least-squared estimation. Furthermore, we repeated all estimations following application of a within-culture standardization procedure for each variable; the estimation results again remained qualitatively unchanged.

5 Discussion

We examined factors affecting individual conformity behavior in Japan and the U.S. We particularly examined individual psychological factors, thereby analyzing motivations for conformist behavior among Japanese and American people.

In Japan, EFFICIENCY significantly affects respondents’ workplace and home conformity, suggesting that Japanese people tend to conform because they believe that it more effectively promotes outcomes. As discussed in Sect. 2, the efficiency motivation for Japanese conformity would come from people’s belief in the economic efficiency of group cooperation, which likely reflects the history of Japan. Most Japanese individuals in the past were rice farmers who needed to cooperate to survive due to scarce natural resources (Benedict 1946; DeVos 1973). A low-mobility society encouraged people to cooperate in the long-run and enabled the group to improve its economic outcomes. Indeed, in Japan, there is the conviction that the group is the most effective working unit (Nakane 1970).

This argument implies that Japanese collectivism may be fundamentally motivated by self-interest. Indeed, Japanese people tend to commit and conform to their group, expecting that they will benefit from it later (Hamaguchi 1982). Moreover, many Japanese workers are self-interested and are willing to share in the fate of their company only to the extent that it promotes their own objectives (Befu 1980).

If Japanese collectivism stems from pragmatism, Japanese people in an unproductive group will leave that group. Previous research has supported this conjecture. For instance, Triandis et al. (1993) show that scores on a particular cultural factor (“Task Emphasis”) are highest in Japan among ten countries, and that scores on this factor are correlated with individuals’ agreement with the statement, “If the group is slowing me down, it is better to leave it and work alone.” Further, Japanese people are more likely to leave a poorly performing group than Americans (Yamagishi 1988). These results suggest that Japanese people particularly tend to leave groups that do not benefit them. Additionally, these results also support our inference that Japanese people behave in collectivist ways to pursue efficiency.

In contrast, EFFICIENCY scores are not significantly correlated with conformity scores in the U.S. sample. This shows that there is less belief in the economic efficiency of group cooperation, which may reflect the environment of the U.S. With relatively plentiful food and land, there is little need for people to increase efficiency through cooperation. Moreover, people experience greater difficulty achieving socially efficient outcomes through cooperation in a highly mobile society such as the U.S. (Bowles and Gintis 2011).

Our results suggest that the institutional differences between Japan and the U.S., which probably reflect differences in social history and environment, would give rise to differences in people’s psychological motivations for group conformity. The Japanese conform to the group’s opinion for the economic benefits of cooperation, but the Americans do not.

Instead, among the factor scores in the U.S. sample, COMFORT principally predicts conformity both at work and at home, indicating that Americans tend to conform because it makes them feel comfortable. This is interesting, as conformity is generally considered to indicate lack of individuality in U.S. society and hence the direct expression of individual opinions is valued (Matsumoto et al. 1996). A considerable proportion of people in the U.S. feel comfortable when conforming (approximately a quarter gave scores of 4 or 5 in response to the COMFORT question; Fig. 2). Moreover, those people tend to conform at home as well as at work (Tables 4, 5, 6 and 7). Thus, collectivist behavior among American people would generally reflect individuals who feel comfortable when conforming.

SATISFACTION does not significantly affect workplace conformity in Japan or the U.S., suggesting that Japanese and American people do not tend to conform at work because they find it satisfying. In contrast, SATISFACTION significantly predicts conformity at home in both Japan and the U.S., suggesting that Japanese and American people behave in collectivist ways at home because they value cooperation with family members for its own sake. The psychological factors motivating collectivist behavior thus vary, depending on the circumstances.

6 Conclusion

This research examined psychological factors motivating collectivist behavior in Japan and the U.S. We found that the Japanese conform to their groups both at workplaces and at home because they consider that cooperation with other group members will result in greater achievement. In contrast, Americans do not conform to their groups for achievement. We conjecture that this difference in psychological motivation for conformity between Japan and the U.S. would arise from institutional differences based on the history and environments of these two countries.

We also found that both Japanese and American respondents conform both at workplaces and at home because it makes them feel comfortable. On the other hand, in both of the countries, people conform at home because they value cooperation with family members for its own sake. Note that we did not detect this type of conformity based on a high valuation of cooperation with other members at workplaces in either Japan or the U.S. These results suggest that motivations for collectivism would substantially differ between home and the workplace.

This paper exclusively analyzed group conformity as a measure of individual collectivism; however, other measures of collectivism are available. Therefore, future research should examine individual motivations for collectivist behavior using other measures.

Notes

Researchers have used various definitions and measures of collectivism; definitions used in earlier research typically considered certain individual behaviors and values related to the individual’s group (e.g., emotional attachment, harmony, cooperation, obedience, prioritization of group interests, and conformity; see Hofstede 1980; Oyserman et al. 2002; Triandis et al. 1993). Among these behaviors and values, conformity is central to typical conceptions of collectivism (Schimmack et al. 2005; Takano and Osaka 1999). Therefore, the current study considers levels of group conformity to indicate individuals’ collectivism.

Talhelm et al. (2014) argue that farmers in rice villages needed to adopt more collectivistic behavior compared to farmers in wheat villages. They predict that these agricultural legacies continue to affect people in the modern world and provide empirical evidence that people from rice provinces (southern China) are more interdependent and collectivistic than people from wheat provinces (northern China).

With respect to the mobility of people in the workplace, it has been said that Japan had low mobility of workers, as seen from the “lifetime employment system” (Abegglen 1958). In fact, Flath (2005) shows that the average tenure of employment was the highest for Japan and the lowest for the U.S. among 10 developed countries in 1991.

We conjecture that analysis of the 2012 results would yield similar results, because the 2006 and 2012 surveys both collected large-scale data from a representative sample of the population of each country and the psychological motivations for collectivist behavior in two large populations seem unlikely to change over 6 years. Nonetheless, it remains possible that public attitudes toward IC in each country would have changed in the interim, particularly following the 2008 global financial crisis and the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake. The financial crisis may have affected collectivism in both countries, and the earthquake may have promoted collectivism in Japan. Future research should examine the effects of these events on public IC in Japan and the U.S., and in other countries.

Previous studies have shown that individual attributes (e.g., age, sex, social class) affect individuals’ degree of collectivism (Triandis 1995).

Regarding W-CONF, some may wonder whether the mean difference observed between Japan and U.S. samples stems from the fact that the proportion of specialists in the U.S. sample was twice as high as that of Japanese sample (Table 1), as specialists may respond with lower scores on the W-CONF than other occupations because they tend to work more individually than as a group. To check this possibility, we compared the W-CONF mean between the two countries, excluding specialists. We found that the mean W-CONF of the Japanese sample (3.103) was still significantly higher (at the 1% level) than that of the U.S. sample (2.131). Similarly, regarding F-CONF, the mean difference between Japan and the U.S. may have stemmed from the larger proportion of single individuals in the U.S. sample than in the Japanese sample (Table 1), as many single people respond with lower scores on the F-CONF measure than those with larger family units. To check this possibility, we compared the mean of F-CONF between the two countries, excluding single people. We found that the mean F-CONF of the Japanese sample (3.202) was still significantly higher (at the 1% level) than that of U.S. sample (2.107).

Previous literature has established the necessity of controlling for national differences in response style in cross-cultural research (Fisher 2004; Fisher and Milfont 2010; Hofstede 1980; Schimmack et al. 2005). We used within-culture standardization (i.e., the mean score across all variables and individuals within a country is subtracted from the individual’s raw score on each specific variable and divided by the standard deviation across all variables and individuals), as this method is appropriate for comparison of means and regression analysis (Fisher 2004).

Nonetheless, collectivism rates in the U.S. may sometimes exceed those in Japan (Oyserman et al. 2002).

CF is often called two-stage residual inclusion (2SRI) in contrast to the method used more often, two-stage predictor substitution, and can be estimated in STATA.

See Eq. (18) in Vella (1993) for the definition of the first-stage generalized residuals in the ordered probit model.

Regarding the dummy variables, such as age, we treated the whole variables together; for example, since age 20 years was significant for W-CONF in the U.S., none of the age dummy variables were included in the instrumental variables but were used as control variables in the second-stage regression. For a robustness check, we also estimated the CF by treating each variable separately: for example, only age 20 years was excluded from and the other age dummies were included in the instrumental variables. However, the results were qualitatively unchanged.

Considering the possibility of sample selection bias in conducting these subsample regressions, we also employed a Heckman two-step procedure: in the first step, we estimated a selection equation of employment participation choice for W-CONF and a selection equation for being single for F-CONF. Then, in the second, we ran the ordered probit regressions of W-CONF and F-CONF by including the inverse Mills ratio. The resultant estimation results remained qualitatively unchanged. In the selection equation for employment participation, we included the individual attribute variables except for the job-status variables (as in Table 1) as explanatory variables, while in the selection equation for being a single person, we included those except for the family structure variables.

References

Abegglen JC (1958) The Japanese factory: aspects of its social organization. Free Press, Glencoe

Akerlof GA, Kranton RE (2010) Identity economics: how our identities shape work, wages, and well-being. Princeton University Press, New Jersey

Aoki M (2010) Corporations in evolving diversity: cognition, governance, and institutions. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Befu H (1980) A critique of the group model of Japanese society. Soc Anal Int J Soc Cult Pract 5(6):29–43

Benedict R (1946) The Chrysanthemum and the sword: patterns of Japanese culture. Houghton Mifflin, Boston

Bond R, Smith PB (1996) Culture and conformity: a meta-analysis of studies using Asch’s (1952b, 1956) line judgement task. Psychol Bull 119(1):111–137

Bowles S, Gintis H (2011) A cooperative species: human reciprocity and its evolution. Princeton University Press, New Jersey

Campbell N, Kean A (2012) American cultural studies: an introduction to American Culture, 3rd edn. Routledge, New York

Castelli L, Vanzetto K, Sherman SJ, Arcuri L (2001) The explicit and implicit perception of in-group members who use stereotypes: Blatant rejection but subtle conformity. J Exp Soc Psychol 37:419–426

Cialdini R, Wosinska W, Barrett D, Butner J, Gornik-Durose M (1999) Compliance with a request in two cultures: the differential influence of social proof and commitment/consistency on collectivists and individualists. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 25:1242–1253

Cross CP, Brown GR, Morgan TJH, Laland KN (2017) Sex differences in confidence influence patterns of conformity. Br J Psychol Soc 108:655–667

DeVos D (1973) Socialization for achievement: essays on the cultural psychology of the Japanese. University of California Press, Berkeley

Fisher R (2004) Standardization to account for cross-cultural response bias: a classification of score adjustment procedures and review of research in JCCP. J Cross Cult Psychol 35(3):263–282

Fisher R, Milfont TL (2010) Standardization in psychological research. Int J Psychol Res 3(1):88–96

Flath, D. (2005) The Japanese Economy (2nd ed). Oxford University Press, New York.

Fudenberg D, Levine DK (2009) A long-run collaboration on long-run games. World Scientific Publishing, Singapore

Gelfand MJ, Bhawuk DPS, Nishii LH, Bechtold DJ (2004) Individualism and collectivism. In: House TJ, Hanges PJ, Javidan M, Dorfman PW, Gupta V (eds) Culture, leadership, and organizations: the GLOBE study of 62 societies. SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks, pp 437–512

Gorodnichenko Y, Roland G (2011) Which dimensions of culture matter for long-run growth? Am Econ Rev 101(3):492–498

Gorodnichenko Y, Roland G (2017) Culture, institutions and the wealth of nations. Rev Econ Stat 99(3):402–416

Greif A (1994) Cultural beliefs and the organization of society: a historical and theoretical reflection on collectivist and individualist societies. J Polit Econ 104:912–950

Greif A (2006) Institutions and the path to the modern economy: lessons from medieval trade. Cambridge University Press, New York

Griskevicius V, Goldstein NJ, Mortensen CR, Cialdini RB, Kenrick DT (2006) Going along versus going alone: when fundamental motives facilitate strategic (non)conformity. J Pers Soc Psychol 91(2):281–294

Guiso L, Sapienza P, Zingales L (2003) People’s opium? Religion and economic attitudes. J Monet Econ 50(1):225–282

Guiso L, Sapienza P, Zingales L (2006) Does culture affect economic outcomes? J Econ Perspect 20(2):23–48

Hamaguchi E (1982) “Nihonteki shudan shugi towa nanika (What is Japanese collectivism?)” In: Hamaguchi E, Kumon S (eds) Nihonteki shudan shugi (Japanese Collectivism). Yuhikaku, Tokyo, pp 1–26

Hofstede G (1980) Culture’s consequences. SAGE Publications, Newbury Park

La Porta R, Lopez-de-Silanes F, Shleifer A (2008) The economic consequences of legal origins. J Econ Literat 46(2):285–332

Matsumoto D, Kudoh T, Takeuchi S (1996) Changing patterns of individualism and collectivism in the United States and Japan. Cult Psychol 2(1):77–107

Nakane C (1970) Japanese society. University of California Press, Berkeley

North DC (1991) Institutions. J Econ Perspect 5(1):97–112

Oyserman D, Coon HM, Kemmelmeier M (2002) Rethinking individualism and collectivism: evaluation of theoretical assumptions and meta-analyses. Psychol Bull 128(1):3–72

Quinn A, Schlenker BR (2002) Can accountability produce independence? Goals as determinants of the impact of accountability on conformity. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 28:472–483

Renkema LJ, Stapel DA, Van Yperen NW (2008) Go with the flow: conforming to others in the face of existential threat. Eur J Soc Psychol 38:747–756

Schimmack U, Oishi S, Diener E (2005) Individualism: a valid and important dimension of cultural differences between nations. Pers Soc Psychol Rev 9(1):17–31

Stock J, Yogo M (2005) Testing for weak instruments in linear IV regression. In: Andrews D, Stock J (eds) Identification and inference for econometric models: essays in Honor of Thomas Rothenberg. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Tabellini G (2008) Institutions and culture: presidential address. J Eur Econ Assoc 6(2–3):255–294

Takano Y, Osaka E (1999) An unsupported view: comparing Japan and the U.S. on individualism/collectivism. Asian J Soc Psychol 2(3):311–341

Talhelm T, Zhang X, Oishi S, Shimin C, Duan D, Lan X, Kitayama S (2014) Large-scale psychological differences within China explained by rice versus wheat agriculture. Science 344(9 May):603–608

Terza J, Basu A, Rathouz P (2008) Two-stage residual inclusion estimation: addressing endogeneity in health econometric modeling. J Health Econ 27(3):531–543

Triandis HC (1995) Individualism and collectivism. Westview Press, Boulder

Triandis HC (2001) Individualism-collectivism and personality. J Pers 69(6):907–924

Triandis HC, Betancourt H, Iwao S, Leung K, Salaza J, Setiadi B, Setiadi B, Sinha JB, Touzard H, Zaleski Z (1993) An etic-emic analysis of individualism and collectivism. J Cross Cult Psychol 24(3):366–383

Vella F (1993) A simple estimator for simultaneous models with censored endogenenous regressors. Int Econ Rev 34(2):441–457

Vogel EF (1979) Japan as number one: lessons for America. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Williamson OE (2000) The new institutional economics: taking stock, looking ahead. J Econ Literat 38(3):595–613

Wooldridge JM (2014) Quasi-maximum likelihood estimation and testing for nonlinear models with endogenous explanatory variables. J Economet 182(1):226–234

Wooldridge JM (2015) Control function methods in applied econometrics. J Human Resources 50(2):420–445

Yamagishi T (1988) Exit from the group as an individualistic solution to the free rider problem in the United States and Japan. J Exp Soc Psychol 24(6):530–542

Yamagishi T, Hashimoto H, Schug J (2008) Preference versus strategies as explanations for culture-specific behavior. Psychol Sci 19(6):579–584

Yamaguchi S (1994) Collectivism among the Japanese: A perspective from the self. In: Kim U, Triandis HC, Kagitcibasi , Choi S-C, Yoon G (eds) Individualism and collectivism: theory, method, and applications. SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks, pp 4175–188

Zingales L (2015) The “Cultural Revolution” in Finance. J Financ Econ 117(1):1–4

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Yasuhiro Arai, Hideshi Itoh, and the participants in the workshop at Kochi University of Technology and Monetary Economics Workshop held at Kansai University for their helpful comments.

Funding

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI [Grant Number 26380416, 26590052, 17K03820, 17K03828, and 18K01673] and the Center of Excellence Project of Osaka University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

None.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix: Calculating marginal effects in ordered probit models

Appendix: Calculating marginal effects in ordered probit models

This appendix discusses the procedure for calculating the marginal effects of the estimated coefficients of independent variables in models (1) and (2). \(y(y = 1,2, \ldots 5)\) represents dependent variables; W-CONF, F-CONF, and \(X(K \times 1)\) represent independent variables. In this context, the expected value of the dependent variable \(E(y|X)\) is defined as follows:

A marginal effect of an independent variable xk , MEk, is therefore defined as follows:

where \(\left. ME_{k}^{j} = \frac{\partial P(y = j|X)}{{\partial x_{k} }}\right|_{{X = \overline{X}}}\). \(\overline{X}\) denotes the sample means of the independent variables (X).

We used the delta method, thereby calculating the standard error of the marginal effect MEk on the independent variable xk as follows:

where \(\sigma_{{ME_{k} }}\) indicates the standard error of the marginal effect MEk, and \(\sigma_{x^{k}}^{j}\) denotes the standard error of \(ME_{k}^{j}\). We calculated the marginal effect (A-1) and its standard error (A-2) for each independent variable in our ordered probit models.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hirota, S., Nakashima, K. & Tsutsui, Y. Psychological motivations for collectivist behavior: comparison between Japan and the U.S. Mind Soc 22, 103–128 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11299-023-00298-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11299-023-00298-y