Most of our activity and most decisions are not innovative, but are governed by “programs” already in existence. There is a distinction between those decisions, on the one hand, that are encountered frequently and repetitively in the daily operations of an organization and those, on the other hand, that represent novel and non-recurring problems for organizations.

Herbert A. Simon (1957)

Abstract

Herbert Simon viewed innovation as a particular type of problem-solving behavior that entails refocus of attention and search for alternatives outside the existing domain of standard operations. This exploration outside of standard routines involves heuristic-based discovery and action, such as satisficing search for information and options. In our observations on the innovation process, we focus on knowledge generation. We propose viewing the process of generating knowledge—when knowledge is sufficient to instigate action, but not necessarily enough to eliminate the uncertainty of the situation—as a heuristic process. Because many personal and organizational decisions are acted upon in the presence of some degree of uncertainty, we argue that heuristics structure the way in which information is processed innovatively. We provide a catalogue of instances in business decision making.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Innovation and tacit knowledge

A searchFootnote 1 for the term innovation in Simon’s numerous writings returned only one title, “The executive’s responsibility for innovation,” a short piece delivered at a summer institute in 1957. In this talk, Simon argues that in order to survive in a changing business arena, executives are charged with designing organizational environments conducive to innovation. Such environments stimulate and facilitate various processes of creativity characterized by Simon as follows (1957, pp. 2–3):

-

1.

Alternatives are not given but must be searched for.

-

2.

It is a major part of the decision-making task to discover what consequences will follow each of the alternatives being considered.

-

3.

We are more often concerned with finding an acceptable alternative than with finding the best alternative. The classical theory of decision was concerned with “optimizing”; a theory of innovation will be concerned with “satisfying.” It can be shown that this change in viewpoint is essential if a satisfactory theory is to be constructed.

-

4.

Problem solving involves not only search for alternatives, but [also] search for the problems themselves.

Simon further points to the inadequacy of rational choice theory for capturing these features and suggests developing an alternative theory capable of conforming to these four elements of the creative processes of innovative action (For a comprehensive account of many concepts of innovation, see Shavinina 2003).

In practice, to deliver on their responsibility of fostering creative activities, managers must excel at regularly delegating the surveillance of once-novel-now-routine operations. This deliberate distance from standard operations is essential to free up time for breeding innovation at an organization. Other requirements include “radars” for scanning the environment, technologically enhanced staff, long-range planning activities, and imagination. In summary, managers’ and employees’ attention and efforts have a tendency to be consumed by the “programmed” operation routines in an organization; innovation, by contrast, requires a deliberate break from routine to make space and provide resources for the “nonprogrammed” operations, which themselves have to be identified by an intelligent search of the environment and by imagining the potential needs and possible improvements outside the familiar settings.

We observe that the process of habitually breaking from routines can itself be viewed as a routine or a heuristic. One may call this routine the innovation heuristic. The main proposal of this paper is that the process of generating knowledge while the innovation heuristic is at work is itself a heuristic, namely that of generating a satisfactory amount of knowledge to set an innovative action in motion. Furthermore, Simon (1957) declares that the many-faced mystery of human thought processes has been reduced by computer simulations to “nothing more than complex sequences of simple processes of selective search and evaluation.”Footnote 2 We emphasize that the simplicity of heuristics is the very property that supports their use as structures for information search in situations of uncertainty, which typify creative/innovative processes.

Finally, new knowledge is both acquired and created in an innovative procedure. The part of knowledge already in place, which can be triggered by the changes in the environment, is referred to as tacit knowledge. Tacit knowledge exists to different degrees, depending on features such as articulation ability, presence of standards, and (not) requiring face-to-face transmission. Viale (2006)Footnote 3 views knowledge on a spectrum from fully codifiable, that is, transformable into propositionals, to completely tacit, that is, uncodifiable, and presents a categorization as in Table 1 (p. 341).

The innovation heuristic can be viewed as involving different degrees of tacitness. In deliberate problem solving, one is aware of paying attention to a certain issue or evoking and utilizing relevant knowledge. In situations that call for heuristic problem solving, attention still plays a major role, whether concurrent with awareness of specifics or not. Next, we demonstrate the important role of attention allocation in every type of problem solving through a famous puzzle that Simon used to discuss with his students in class.

2 Attention and heuristic problem solving

Attention is a main element of Simon’s analysis of problem-solving behavior. Attention’s focus, its limitations, the seriality associated with its operation, and its relation to multiple simultaneous goals are among the many aspects of this analysis (Simon 1986, p. 10): “Focus of attention play[s] a great role in determining priorities. And so we see that, both with respect to subdivisions of organizations and with respect to different periods of time, human bounded rationality and limited capability for parallelism of thought and action is constantly changing the effective goals—always partial goals—toward which action is directed.” Attention is thus a resource that can be allocated to tasks conditioned on seriality and other limitations. Problem solving involves focus of attention and trial of potential solutions until one is found that satisfactorily resolves the problematic situation. Interestingly, finding a solution may include showing that the problem at hand cannot be solved, as the following example clarifies.

2.1 Example: the mutilated chessboard problem

A regular chessboard with 64 squares (32 of each color) can be covered with 32 domino tiles each the size of two squares. If two opposite corners of a chessboard are removed, it leaves a mutilated board with 8 × 8 − 2 = 62 squares. Can one cover this board with 31 of these domino tiles? Figure 1 visualizes the impossibility of doing so. In an interview (with Love 2002), Simon explains the solution process: Individuals first try a few ways of covering the board with domino tiles until they realize that each tile must cover exactly one square of each of the two colors. But because two of the same color have been removed, two squares of the other color are left over, which reveals the impossibility of solving this problem.

(adopted from Sampath et al. 2014)

Mutilated chessboard problem illustrated

Thus, solving a problem can include arriving at its nonsolvability. This is only one special case. In general, solving a problem can involve finding alternatives that are not among the primary options. In the case of an organization, Simon (1957) refers to these as non-programmed actions. For a programmed case, on the other hand, standard routines are sufficient. Notably, as alluded to before, actions can be viewed as resulting from heuristic processes in both programmed and nonprogrammed cases. For example, routines usually economize on resources, among other ways by ignoring some of the available information or by focusing attention on a subset of information. A common conception of heuristics is that of actions based on routines and habits. As such and in terms of structure, a heuristic can be decomposed into three rules for search, stopping search, and making a decision. Searching can, for example, be random or in a certain order, and a preset aspiration level can serve as a stopping rule. Classification of heuristic routines that are used in problem solving (or decision making) comprises the four categories listed below (for explanations in relation to psychology, see Gigerenzer and Gaissmaier 2011, and in relation to behavioral economics, see Mousavi et al. 2017):

-

1.

Recognition-based decision making: Evaluate options based on their being recognized.

-

2.

Sequential consideration: Consider cues in a simple order such as a lexicographical one; stop consideration as soon as a decision can be made (Special case: Base decision on a single cue.)

-

3.

Equal weighing: Assign simple—0/1 or equal—weights. Forgo estimating weights to reduce estimation error.

-

4.

Satisficing: Choose the first option that meets an aspiration level. (Consideration of information does not follow a sequence ordering.)

Satisficing behavior is the poster child for heuristic processes (Mousavi 2002 and Mousavi and Tideman 2019). As we saw earlier, it is also the process that Simon uses to describe innovative and creative action. For exploring new ideas and solving novel problematic situations, not having all the information is viewed by Simon as a potential advantage, a “secret weapon”—one that enabled him to make so many fundamental contributions across different fields of study as a partially ignorant enthusiast who was capable of viewing a discipline through the lens of another one (Langley 2001, 2004; also see Love’s [2002] interview with Simon). Next, we conceptualize heuristic procedures as ones that can capture a certain type of knowledge generation associated with innovative activity. This argument constitutes the main contribution of the current article.

3 Innovation as heuristic generation of knowledge

We suggest that heuristics can be viewed as processes that can generate sufficient knowledge for action under situations of Knightian uncertainty (Knight 1921). Such situations are mainly characterized by unknowable factors at the time of action. Relatedly, innovation, when actualized, can be viewed as transformation of previously unknown relations—between a set of both known and unknown outcomes—to knowable operational relationships. The actualization of innovation requires some actionable knowledge, which can be generated without attempting to make all unknowns knowable, that is, to make all tacitness explicit. In that vein, heuristics can be viewed as cognitive tools that ignore information or do not attempt to exhaust information before arriving at an action or decision. Furthermore, intuition (fully tacit knowledge) can be understood as a heuristic, where a person knows what to do but cannot explain why (Gigerenzer 2007). Bringing all of these notions together, we propose heuristics as knowledge-generating processes under uncertainty that cannot be reduced to risk representation. Additionally, we argue that because knowledge generated on the basis of opinion or intuition [both terms used by Knight (1921)] is not the same as inductive inference per se, these processes can be distinguished from induction—and by extension from deduction. Induction, in particular, is at the root of generating experimental knowledge (Mayo 1996). Here, our claim is that innovative action results from just enough knowledge generated by cognitive heuristics. Admittedly, this claim is at best a plausible initial step towards developing a theory of heuristics that can account, among other items, for innovative and creative actions. The following puts together the authors’ current thoughts on this topic, and aims at eliciting feedback and discussion.

3.1 The connection between heuristics and entrepreneurship

Consider entrepreneurship as innovative businessmanship. Hayward et al. (2010) posit that successful entrepreneurship is about creating knowledge on novel fronts and expanding a thought-action creatively. Heuristic processes, as argued before, can form opinions that lead to creative actions. In what follows, the familiar processes of knowledge creation are extended to include heuristics as an information-processing mechanism in addition to deduction and induction. The type of knowledge created as a result of such processes is conducive to creativity and novelty of thoughts that can lead to entrepreneurial undertaking of actions, and therefore to innovation in a general sense. This framework extends on a fundamental distinction between risk and uncertainty (see, e.g., Mousavi and Gigerenzer 2017), which connects entrepreneurial activities to uncertainty à la Knight and further establishes heuristics as befitting strategies for dealing with complexities of uncertain novelty, introduced next.

4 From Knightian uncertainty to knowledge generation

Knight (1921) argues that profit generation in competitive markets must be understood by differentiating between decision making under risk and under uncertainty. Knight claims that only some unknown situations can be characterized by a form of risk that can be quantified by probabilities. He defines a risky situation as one that can be hedged. If the situation lends itself to an underlying specifiable structure of the distribution of events, such as propensities, then it is represented and measured by a priori probability. Otherwise, when probabilities are arrived at through statistical inference, Knight refers to the risky situation being measurable by statistical probability. Knightian uncertainty, on the other hand, signifies situations with features that cannot be reduced to risk calculation and thus does not allow for probabilistic quantification. In these uncertain situations, Knight contends that decisions are made based on estimatesFootnote 4 that emerge from forming opinions and relying on intuition. Knight then asserts that profit making from entrepreneurial actions in competitive markets falls under the realm of uncertainty, not risk:

But the probability in which the student of business risk is interested is an estimate, though in a sense different from any of the propositions so far considered. To discuss the question from this new point of view we must go back for a moment to the general principles of the logic of conduct. We have emphasized above that the exact science of inference has little place in forming the opinions upon which decisions of conduct are based, and that this is true whether the implicit logic of the case is prediction on the ground of exhaustive analysis or a probability judgment, a priori or statistical. We act upon estimates rather than inferences, upon “judgment” or “intuition,” not reasoning, for the most part. (Knight 1921, p. 34)

Drawing on this notion of uncertainty and its relation to acting based on what Knight calls an estimate, Fig. 2 depicts how a further step can be taken to connect each type of risk, as well as Knightian uncertainty, to a different form of knowledge generated in the process of acting under each of this situations.

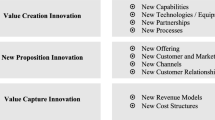

4.1 Heuristics as tools are special lower-level cases of heuristics as knowledge generators

If heuristic processes provide a structure for understanding the way in which actionable knowledge is generated under uncertainty, then the next logical connection is conjectured as follows. Innovation is the result of acting in situations where knowability remains at a weak level, and it leads to additional knowledge or some creation of knowledge. When the sources of such actions are specified as a heuristic process of decision making, an operational framework emerges that characterizes innovation as a heuristic-generating mechanism of knowledge. This endeavor, admittedly a long-term one, comprises a metalevel of formulating heuristics. Such an effort is rendered plausible for one by the fact that heuristic strategies—not at a metalevel but as tools—have organically emerged as successful ways of making decisions in finance and business. Each of such instances can be regarded as a special case for a lower-level analysis of the main claim of the authors. Table 2 summarizes a collection of evidence for successful uses of heuristics in business decision making.

The instances catalogued in Table 2 share one common feature: Professionals systematically develop and successfully use heuristics. This adds to the body of empirical evidence, which Simon (1977) viewed as the basis for constructing a behavioral theory of action. More precisely, this line of inquiry follows his very method for the study of the logic of heuristics: “to point to what sophisticated practitioners actually do: to show that they reason rigorously about action without needing a logic of action (1977, p. 155).” Simon’s emphasis on what people actually do as opposed to what they should do is an alternative and fruitful focus for the study of human behavior and a main thrust of his extensive agenda, mostly recognized under the umbrella term of bounded rationality (Mousavi 2018).

5 Closing the argument

Per his tradition, Simon discusses behavior only in relation to context, never in isolation. Innovation for Simon (1957) is an adaptive behavior in response to novel demands or changes in the environment. In particular, he holds that innovation in an organization must be facilitated and elicited by executives in response to the changes in their operative environment beyond the programmed standard operating procedures already in place. As the epigraph states, innovation constitutes a minority of our activities in daily life; in an organization, this is the nonprogrammed part of operations. Innovative program building involves difficult search and a recognition of fleeting opportunities within the environment (Sull and Eisenhardt 2015). Search for new solutions requires learning new techniques and approaches to problems. This, in turn, involves different degrees of tacit knowledge.

Customarily, the generation of experimental and empirical-based knowledge is methodically understood through inductive inferential processes (Mayo 1996). Similarly, albeit at a different level, heuristic strategies have been formulated and represented as inductive processes (Gigerenzer 2008). On the other hand, innovation in the world of business can be viewed as action under irreducible uncertainty, where the unknowable situation is handled on the basis of an opinion or intuition, as in entrepreneurial decision making (Knight 1921). The present article expanded on the beneficial degree of ignoring information as a characterizing feature of heuristics that in turn lends itself to viewing heuristics as generating sources of actionable knowledge. This viewpoint was illustrated by examples of successful uses of heuristics in making business decisions with partial utilization of information. These were argued to be analogous to innovation as an action that is less than fully identifiable.

Famously, and at a general level, Simon introduced satisficing procedures as a descriptive form for modeling and understanding behavior. A start to building a theory of innovation in the Simonian sense can be envisioned by observing the innovative behavior of boundedly rational agents who use heuristics, such as executives in organizations. When the heuristics are used successfully in novel contexts, analyzing them in relation to the conditions in which they have proven useful provides us with building blocks for an empirically based theory of innovation and creativity, both of which can be understood and viewed as heuristic problem-solving behaviors.

Notes

This returned from a Google search of “Herbert Simon + innovation.” To verify that it is indeed the only title containing innovation, we conducted a search through the bibliography of Herbert A. Simon on the Carnegie Mellon website, where the only result is found here: http://www.psy.cmu.edu/psy/faculty/hsimon/HSBib-1930-1950.html. Creativity, a related term, appears more often in Simon’s writings, e.g., Simon (1985).

This is a central point that has been further clarified and discussed by Newell, Shaw, and Simon (1958).

Viale provides this definition of tacit knowledge from the sociology of science as one that allows for identifiability: “knowledge or abilities that can be passed between scientists by personal contact but cannot be, or have not been, set out or passes on in formulae, diagrams, or verbal descriptions and instructions for action” (Collins, 2001, p. 72).

Notice that this specific meaning of estimate differs from that of a statistical estimation of parameters involving specifiable errors and such.

References

Azar OH (2014) The default heuristic in strategic decision making: when is it optimal to choose the default without investing in information search? J Bus Res 67(8):1744–1748

Berg N (2014) Success from satisficing and imitation: entrepreneurs’ location choice and implications of heuristics for local economic development. J Bus Res 67(8):1700–1709

Collin HM (2001) Tacit knowledge, trust, and the Q of sapphire. Soc Stud Sci 31:71–85

Fifić M, Gigerenzer G (2014) Are two interviewers better than one? J Bus Res 67(8):1771–1779

Gigerenzer G (2007) Gut feelings: the intelligence of the unconscious. Viking Press, New York

Gigerenzer G (2008) Why heuristics work. Perspect Psychol Sci 3:20–29

Gigerenzer G, Gaissmaier W (2011) Heuristic decision making. Annu Rev Psychol 62:451–482

Hauser JR (2014) Consideration-set heuristics. J Bus Res 67(8):1688–1699

Hayward MLA, Forster WR, Sarasvathy SD, Fredrickson BL (2010) Beyond hubris: how highly confident entrepreneurs rebound to venture again. J Bus Ventur 25:569–578

Hu Z, Wang XT (2014) Trust or not: heuristics for making trust-based choices in HR management. J Bus Res 67(8):1710–1716

Knight FH (1921) Risk, uncertainty and profit. Dover 2006 unabridged republication of the edition published by. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston and New York

Langley P (2001) Heuristics for scientific discovery: legacy of Herbert Simon. Adapted from a presentation at the 2001 meeting of the Cognitive Science Society for the Herbert A. Simon panel and a chapter in Augier ME, March JG (eds) Models of a man: essays in memory of Herbert A. Simon. MIT Press, Cambridge

Love J (2002) A conversation with Herb Simon. http://doi.library.cmu.edu/10.1184/pmc/simon/box00000/fld00000/bdl0000/doc0001

MacGillivray BH (2014) Fast and frugal crisis management: an analysis of rule-based judgment and choice during water contamination events. J Bus Res 67(8):1717–1724

Mayo DG (1996) Error and the growth of experimental knowledge. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Monti M, Pelligra V, Martignon L, Berg N (2014) Retail investors and financial advisors: new evidence on trust and advice taking heuristics. J Bus Res 67(8):1749–1757

Mousavi S (2002) Methodological foundations for bounded rationality as a primary framework. Doctoral Dissertation. http://theses.lib.vt.edu/theses/available/etd-12222002-183717/

Mousavi S (2018) Behavioral policymaking with bounded rationality. In: Viale R, Mousavi S, Alemanni B, Filotto U (eds) The behavioural finance revolution: a new approach to financial policies and regulations. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham

Mousavi S, Gigerenzer G (2014) Risk, uncertainty, and heuristics. J Bus Res 67(8):1671–1678

Mousavi S, Gigerenzer G (2017) Heuristics are tools for uncertainty. J Homo Oeconomicus 34:361–379

Mousavi S, Tideman TN (2019) The rise of procedural economics. In: Viale R (ed) The handbook of bounded rationality. Routledge, London

Mousavi S, Gigerenzer G, Kheirandish R (2017) Rethinking behavioral economics through fast-and-frugal heuristics. In: Frantz R, Chen S, Dopfer K, Mousavi S (eds) Routledge handbook of behavioral economics. Routledge, London, pp 280–296

Newell A, Shaw JC, Simon HA (1958) Elements of a theory of human problem-solving. Psychol Rev 65(3):151–166

Nikolaeva R (2014) Interorganizational imitation heuristics arising from cognitive frames. J Bus Res 67(8):1758–1765

Persson A, Ryals L (2014) Making customer relationship decisions: analytics v rules of thumb. J Bus Res 67(8):1725–1732

Rusetski A (2014) Pricing by intuition: managerial choices with limited information. J Bus Res 67(8):1733–1743

Sampath H, Rajeshuni R, Indurkhya B (2014). Cognitively inspired task design to improve user performance on crowdsourcing platforms. In: Conference on human factors in computing systems—proceedings. https://doi.org/10.1145/2556288.2557155

Shavinina LV (2003) The international handbook on innovation. Elsevier, Oxford

Shefrin H, Nicols CM (2014) Credit card behavior, financial styles, and heuristics. J Bus Res 67(8):1679–1687

Simon HA (1957) The executive’s responsibility for innovation in summer program in executive development for federal administrators. University of Chicago. http://digitalcollections.library.cmu.edu/awweb/awarchive?type=file&item=58179. Accessed 3 Nov 2018

Simon HA (1977) The logic of heuristic decision making. In: Models of discovery and other topics in the methods of science. Boston studies in the philosophy of science book series (BSPS), vol 54, pp 154–175

Simon HA (1985) What we know about the creative process. In: Kuhn RL (ed) Frontiers in creative and innovative management. Ballinger, Cambridge, pp 3–22

Simon HA (1986) Keieisha no yakuwa sai tozure (The functions of the executive revisited). In: Kato K, Meshino H (eds) Banado: Gendai shakai to soshiki mondai (pp. 3–17). [Commemorative papers for the centenary of C.I. Barnard’s birth.] Tokyo, Japan: Bunshindo. http://digitalcollections.library.cmu.edu/awweb/awarchive?type=file&item=38869. Accessed 5 Nov 2018

Sull DN, Eisenhardt KM (2015) Simple rules for a complex world. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, Boston

Viale R (2006) Methodological cognitivism. Vol. 2: Cognition, science, and innovation. Springer, Berlin

Acknowledgements

Open access funding provided by Max Planck Society. The authors wish to thank participants at the SABE/IAREP 2016 conference at Wageningen University in the Netherlands for helpful comments and discussions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Kheirandish, R., Mousavi, S. Herbert Simon, innovation, and heuristics. Mind Soc 17, 97–109 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11299-019-00203-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11299-019-00203-6