Abstract

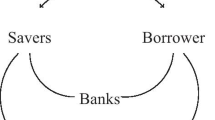

This paper discusses the determinants of a Non-Fiat Anonymous Digital Payment Method’s (N-FAD) value and illustrates a relationship between N-FAD transactions, economic growth, and inflation. The relationship raises a heretofore unmentioned issue concerning the ability of monetary authorities to operate effectively, which justifies regulatory concerns over bitcoin and other N-FADs. Our method of analysis allows for empirical estimates that characterize the magnitude of the concern, as it relates to the use of bitcoin. Finally, we are able to identify the stylized features of bitcoin that complicate monetary policy, comment on how they relate to the value of N-FADs more generally, and provide suggestions for future research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Selgin (2015) categorized monies according to not only their intrinsic value, but also according to their scarcity being absolute or contingent on a decision maker, thus deriving four species of money. What the author denoted “synthetic commodity” money is what this paper refers to as non-fiat anonymous digital payment methods.

According to the Stamp Payments Act of 1862, “Whoever makes, issues, circulates, or pays out any note, check, memorandum, token, or other obligation for a less sum than $1, intended to circulate as money or to be received or used in lieu of lawful money of the United States, shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than six months, or both”. (Stamp Payments Act of 1862, 18 U.S.C. §336, , p. 98)

All transactions of bitcoin between virtual wallets are recorded in a public ledger. Therefore, the transactions are anonymous so long as users keep their wallet ID private. Since the fixed cost of creating a new wallet is essentially zero, many users who value the anonymity create a new wallet for every transaction.

Hypothetically, if a single entity were to control over half of the bitcoin network’s computing power, it could change the supply of bitcoin. However, the simulations run in Nakamoto (2008) showed the hypothetical situation to be a practical impossibility.

We thank an anonymous reviewer for pointing this out.

Taking the total differential of both sides of the equation of exchange yields: ΔMV + MΔV = ΔPQ + PΔQ. Assuming velocity is a unitary constant and dividing by M = PQ gives Eq. 1.

Of course nothing up to this point in the model has distinguished the N-FAD from the fiat currency. We have simply assumed two currencies in a single economy.

As of the writing of this paper, bitcoin’s market capitalization exploded to $110 billion while Ripple’s increased to $17 billion and a new currency, Ethereum has overtaken Ripple’s place behind bitcoin with a market capitalization of $20 billion.

Although the model assumes velocity is constant, the M2 measure of velocity did not change greatly over the time period and replacing it with the average value in the time frame does not alter the predictions substantially.

The trade data on Bitcoincharts (2018) is self-reported by the exchanges and so is not guaranteed to contain all currency trades. In particular, it will not include currency trades that occurred between private parties not using exchanges.

Badev and Chen (2015) may provide a better measure of bitcoin used to purchase goods and services as the authors measured how active wallets are a function of the period of time between transactions. One could potentially calculate a direct estimate of the number of times a bitcoin changes wallets for the purpose of a purchase verses the purpose of masking transactions. This would involve assumptions on what type of behavior is likely masking activity.

References

Badev, A., & Chen, M. (2015). Bitcoin: technical background and data analysis. Morrisville: Lulu Press.

Bitcoincharts. (2018). Charts available from https://bitcoincharts.com/charts. Accessed 07 July 2015.

Blockchain. (2018). Blockchain charts available from http://www.blockchain.info/charts. Accessed 07 July 2015.

Böhme, R., Christin, N., Edelman, B., Moore, T. (2015). Bitcoin: economics, technology, and governance. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 29(2), 213–38.

Bovaird, C. (2017). Why bitcoin prices have risen more than 400% this year. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/cbovaird/2017/09/01/why-bitcoin-prices-have-risen-more-than-400-this-year/#5616aa46f682. Accessed 01 Jan 2019.

Chavez-Dreyfuss, G. (2018). Cryptocurrency exchange theft surges in first half of 2018: report. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-crypto-currencies-ciphertrace/cryptocurrency-exchange-theft-surges-in-first-half-of-2018-report-idUSKBN1JT1Q5. Accessed 01 Jan 2019.

Cheah, E.T., & Fry, J. (2015). Speculative bubbles in bitcoin markets? An empirical investigation into the fundamental value of bitcoin. Economics Letters, 130, 32–36.

Cheung, A., Roca, E., Su, J.J. (2015). Crypto-currency bubbles: an application of the Phillips-Shi-Yu (2013) methodology on Mt. Gox bitcoin prices. Applied Economics, 47(23), 2348–2358.

Chuen, D.L.K. (Ed.). (2015). Handbook of digital currency: bitcoin, innovation, financial instruments and big data. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Coinbase.com. (2015). What is coinbase and how much does it cost to use? https://support.coinbase.com/customer/portal/articles/585625-what-is-coinbase-and-how-much-does-it-cost-to-use-. Accessed 13 Feb 2013.

CoinMarketCap. (2018). Top 100 cryptocurrencies by marked capitalization. https://coinmarketcap.com. Accessed 30 Oct 2018.

Corbet, S., Lucey, B., Yarovaya, L. (2018). Datestamping the bitcoin and ethereum bubbles. Finance Research Letters, 26, 81–88.

Dawkins, D. (2018). Has CHINA burst the bitcoin BUBBLE? Trading in RMB drops from 90% to 1%. Express. https://www.express.co.uk/finance/city/986552/Bitcoin-price-ripple-cryptocurrency-ethereum-BTC-to-USD-XRP-news-china. Accessed 08 Jan 2019.

Dotson, K. (2011). Third largest bitcoin exchange bitomat lost their wallet, over 17,000 bitcoins missing. siliconANGLE. http://siliconangle.com/blog/2011/08/01/third-largest-bitcoin-exchange-bitomat-lost-their-wallet-over-17000-bitcoins-missing. Accessed 30 Sep 2011.

Dwyer, G.P. (2015). The economics of bitcoin and similar private digital currencies. Journal of Financial Stability, 17, 81–91.

Dyhrberg, A.H. (2016). Hedging capabilities of bitcoin. is it the virtual gold. Finance Research Letters, 16, 139–144.

Fry, J., & Cheah, E.T. (2016). Negative bubbles and shocks in cryptocurrency markets. International Review of Financial Analysis, 47, 343–352.

Hendrickson, J.R., & Luther, W.J. (2017). Banning bitcoin. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 141, 188–195.

Internal Revenue Service. (2014). Notice 2014-21. https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-drop/n-14-21.pdf. Accessed 08 Jan, 2019.

Jaewon, K. (2017). South Korea joins in Asia-wide bitcoin crackdown. Nikkei Asian Review. https://asia.nikkei.com/Economy/South-Korea-joins-in-Asia-wide-bitcoin-crackdown. Accessed 08 Jan 2019.

Lo, S., & Wang, J.C. (2014). Bitcoin as money? Current Policy Perspectives, No. 14-4, Federal Reserve Bank of Boston. https://www.bostonfed.org/-/media/Documents/Workingpapers/PDF/cpp1404.pd.Accessed30Oct2018.

McMillan, R. (2014). The inside story of Mt. Gox, bitcoin’s $460 million disaster. WIRED. http://wired.com/2014/03/bitcoin-exchange. Accessed 07 Jan 2019.

Meiklejohn, S., Pomarole, M., Jordan, G., Levchenko, K., McCoy, D., Voelker, G.M., Savage, S. (2013). A fistful of bitcoins: characterizing payments among men with no names. In Proceedings of the 2013 conference on internet measurement conference. https://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=2504747 (pp. 127–140): ACM.

Money Morning. (2014). Check out how many overstock sales are done using bitcoin. https://web.archive.org/web/20150731164413/, http://moneymorning.com/2014/08/15/check-out-how-many-overstock-sales-are-done-using-bitcoin/. Accessed 07 Jan 2019.

Nadarajah, S., & Chu, J. (2017). On the inefficiency of bitcoin. Economics Letters, 150, 6–9.

Nakamoto, S. (2008). Bitcoin: a peer-to-peer electronic cash system. https://bitcoin.org/bitcoin.pdf. Accessed 07 July, 2015.

Overstock.com. (2018). tZERO issues preferred tZERO security tokens. http://investors.overstock.com/phoenix.zhtml?c=131091&p=irol-newsArticle&ID=2371923. Accessed 30 Oct 2018.

Selgin, G. (2015). Synthetic commodity money. Journal of Financial Stability, 17, 92–99.

Stamp Payments Act of 1862, 18 U.S.C §336 (2012).

Tobin, J., & Golub, S.S. (1997). Money, credit, and capital. New York: McGraw Hill.

Urquhart, A. (2016). The inefficiency of bitcoin. Economics Letters, 148, 80–82.

Walsh, C. (2010). Monetary theory and policy. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Yelowitz, A., & Wilson, M. (2015). Characteristics of bitcoin users: an analysis of google search data. Applied Economics Letters, 22(13), 1030–1036.

Young, J. (2017). Much WOW: bitcoin price at all-time high closing on $3,000, main reasons. Coin Telegraph. https://cointelegraph.com/news/much-wow-bitcoin-price-at-all-time-high-closing-on-3000-main-reasons. Accessed 30 Oct 2018.

Acknowledgements

Funding for this research was provided by the CSU Chancellors office through California State Polytechnic University. We would like to thank Gabriele Camera, Edmond Wu, and an anonymous reviewer for useful comments that improved this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hunter, G.W., Kerr, C. Virtual Money Illusion and the Fundamental Value of Non-Fiat Anonymous Digital Payment Methods. Int Adv Econ Res 25, 151–164 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11294-019-09737-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11294-019-09737-4