Abstract

This paper explores whether similarities in production structures have been an important determinant of business cycle co-movement in the Euro Area. We constructed an index of cross-country differences in industry composition using value added data from 62 sectors. Then we tested whether this specialization index can explain several measures of cross-country output and employment co-movement within the European Monetary Union between 1999 and 2016. The results indicate that changes in real gross domestic product exhibit a stronger correlation between countries producing similar goods and services. However, the composition of output cannot explain co-movement in employment or unemployment. We checked the robustness of the results by dividing the sample period and by adding several control variables, including bilateral trade intensity and differences in country risk spreads.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The Stability and Growth Pact has been in place since the inception of the euro in 1999. That agreement limits budget deficits and government debt to 3% and 60% of gross domestic product, respectively.

This includes both industry-specific supply shocks, such as productivity improvements that only affect certain sectors, and industry-specific demand shocks, such as changes in preferences that favor some types of products over others.

Gachter et al. (2017) also studied factors affecting business cycle co-movement in the Euro Area, but they did not consider the role of industry composition.

Luxembourg was excluded due to missing data.

Imbs (1999) and Kalemli-Ozcan et al. (2001) used alternative specialization indices. Imbs (1999) used a correlation coefficient between sectoral shares. Kalemli-Ozcan et al. (2001) measured how sectoral shares for each country differ from the average country (rather than calculating bilateral differences).

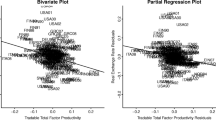

Some authors have measured business cycle co-movement by comparing cyclical deviations from a trend (Bocola 2006; Imbs 2004) while others have used growth rates (Otto et al. 2001) or both (Imbs 1999). Both approaches are imperfect. On one hand, differences in growth rates may also reflect differences in long-run trends. One the other hand, filters that extract the cyclical component may fail to perfectly differentiate between cycle and trend. In this section both approaches were used. Since the initial results were similar, in the next section only results for cyclical deviations are presented.

The results were similar when Ireland, which reported an abnormal 26% real GDP growth rate in 2015, was excluded from the sample.

In addition to using a different group of countries over a different period, our study also differs in the number of sectors used.

Results for real GDP growth rates are similar but omitted for conciseness.

The Durbin-Wu-Hausmann test rejects exogeneity for DEBT at 5% and for SPREAD at 1% when they are the only regressor. It rejects exogeneity for GDPCAP at 1% when the regression also includes SI.

By contrast, Imbs (1999) found that income per capita stops being significant when specialization is taken into account. According to his results, countries with similar income per capita have more synchronized business cycles only because they have similar production structures.

For the second sub-period, instruments for SI, SPREAD and GDPCAP correspond to the values of those variables in 2007.

References

Bocola, L. (2006). Trade and business-cycle comovement: Evidence from the EU. Rivista di Politica Economica, 96(6), 25–62.

Bordo, M., & Helbling, T. (2004). Have national business cycles become more synchronized? In H. Siebert (Ed.), Macroeconomic policies in the world economy. Berlin: Springer.

Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) (2017). Data retrieved from the CIA World Factbook (https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook) on August 3, 2017.

Clark, T., & Wincoop, E. (2001). Borders and business cycles. Journal of International Economics, 55(1), 59–85.

Corinthas, C. (2007). Intra-industry trade and business cycles in ASEAN. Applied Economics, 39(7), 893–902.

European Commission (1990). One market, one money: An evaluation of the potential benefits and cost of forming an economic and monetary union. European Economy, 44.

Eurostat (2017). Data retrieved from Eurostat (http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat) on June 22, 2017.

Frankel, J., & Rose, A. K. (1997). Is EMU more justifiable ex post than ex ante? European Economic Review, 41(3), 753–760.

Frankel, J., & Rose, A. K. (1998). The endogeneity of the optimum currency area criteria. Economic Journal, 108(449), 1009–1025.

Gachter, M., Gruber, A., & Riedl, A. (2017). Wage divergence, business cycle co-movement and the currency effect. Journal of Common Market Studies, 55(6), 1322–1342.

Imbs, J. (1999). Co-Fluctuations. CEPR Discussion Paper no. 2267, Center for Economic Policy Research: London.

Imbs, J. (2004). Trade, finance, specialization, and synchronization. Review of Economics and Statistics, 86(3), 723–734.

International Monetary Fund (2017). Data retrieved from the IMF’s Direction of Trade Statistics (http://data.imf.org/) on August 2, 2017.

Kalemli-Ozcan, S., Sorensen, B. E., & Yosha, O. (2001). Economic integration, industrial specialization, and the asymmetry of macroeconomic fluctuations. Journal of International Economics, 55(1), 107–137.

Krugman, P. (1991). Geography and trade. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Krugman, P. (1993). Lessons of Massachusetts for EMU). In F. Giavazzi & M. Torres (Eds.), Adjustment and growth in the European Union. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

McKinnon, R. (1963). Optimum currency area. American Economic Review, 53(4), 717–725.

Mundell, R.A. (1961). A theory of optimum currency areas. American Economic Review, 51(4), 657–665.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (2018). Data retrieved from OECD. Stat (http://stats.oecd.org/) on March 7, 2018.

Otto, G., G. Voss and L. Willard (2001). Understanding OECD output correlations. RBA Research Discussion Papers 2001–05, Reserve Bank of Australia: Sydney.

Shin, K., & Wang, Y. (2003). Trade integration and business cycle synchronization in East Asia. Asian Economic Papers, 2(3), 1–20.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Azcona, N. Specialization and Business Cycle Co-Movement in the Euro Area. Atl Econ J 47, 193–204 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11293-019-09618-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11293-019-09618-5