Abstract

This paper exploits a unique panel data set of Spanish manufacturing firms that contains information on vertical restraints affecting retailers and wholesalers. First, we analyze the scope of vertical restraints by identifying industry and size heterogeneities. Second, we explore the determinants of resale price maintenance by focusing on the effect of an upstream firm’s effort to increase demand. After presenting a simple theoretical framework, we use a linear probability model to analyze the empirical determinants of a manufacturing firm’s control of the resale price. We find that firms that make a greater advertising effort impose a resale price more frequently, as do larger firms and those that impose other restraints such as exclusive territories.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Some authors include as price restraints (i) the franchise fee, which is a two-part tariff that combines a lump-sum fee and a per-unit price set at the marginal cost and (ii) any kind of royalties, which are usually based on the distributor’s sales levels.

Antitrust regulation in Europe is not the same for all these types. Although minimum prices are forbidden, maximum and recommended prices are not.

For example: when a manufacturer launches a general product promotion, the dealer might encourage consumers to buy another brand. Also, when a manufacturer makes an investment that reduces the retailer’s cost, other brands may benefit from that investment.

Rey and Stiglitz (1988, 1995) show that exclusive territories eliminate intra-brand competition between retailers and act as a pre-commitment agreement to be less “aggressive,” which incentivizes rival manufacturers to set higher prices. Rey and Vergè (2010) analyze RPM in a context where rival manufacturers distribute their products through the same competing retailers. They show that RPM indeed limits the exercise of competition at both levels and can generate industry-wide monopoly pricing.

Jullien and Rey (2007) show that RPM increases the likelihood of collusion by eliminating the retail price variation that makes price cuts easier to detect.

The recent paper of Asker and Bar-Isaac (2014) discusses the effects of different vertical restraints on the exclusion of rivals. In particular they found that both the incumbent manufacturer and retailers stand to gain from RPM, and either side might initiate RPM for the purpose of exclusion.

Comanor and Rey (1997) compare the evolution in attitudes of the US and EU competition authorities.

See the European Commission notice of 10 May 2010: Guidelines on Vertical Restraints, see also Regulation (EU) No. 330/2010, the Block Exemption Regulation (BER), which provides a safe harbor for most vertical agreements.

At the beginning of the survey period, firms with no more than 200 workers were sampled randomly by industry and size strata. Five percent of these randomly sampled firms were included in the sample. All firms with more than 200 workers were asked to participate, and 60 % of them responded.

Fixed book pricing is legally regulated in Spain. Booksellers are only permitted to sell books at the prices set by the publishers, during a period of time. Maximum discounts are also regulated in special days and for public administration. The one exception is schoolbooks, which have not been subject to fixed book prices since 2007. The objective of this regulation is to promote non-price competition between booksellers in order to promote culture and reading. This regulation has been criticized by the Spanish competition authority: http://www.cnmc.es/Portals/0/Ficheros/Promocion/Informes_y_Estudios_Sectoriales/1997/1.pdf (last access 12-18-2014).

Gilligan (1986) offers an empirical examination of RPM’s competitive effects.

This benchmark case is Spengler’s (1950) model, which illustrates the double marginalization problem that occurs when a downstream monopoly chooses an excessive price without accounting for its negative effect on the upstream firm.

We are supposing here that both the manufacturer and retailer are monopolists; this is an extreme case, but the main conclusions are similar when they each have only some monopolistic power. Recall that this simple model applies in a context of intra-brand competition, abstracting from the case of interaction with other suppliers.

If we considered other types of effort, in particular, pre-sale and/or post-sale assistance, then it would probably be necessary to include variable costs of service provision because each unit sold requires a higher cost of effort.

For simplicity, we assume a zero cost of resale.

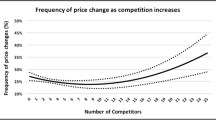

This result can be extended to the case of a downstream Cournot oligopoly. In this case, it is easy to show that the profit increase due to vertical integration is decreasing in the number of distributors.

We included the observations of those firms that provided information about all variables. A total of 106 observations were discarded because they did not report the data needed for some variables used in the estimation; we also discarded observations of the first period in order to build the lags. Finally, we did not consider any firms in the “other transport materials” sector because none of them admit to participating in resale price maintenance.

We use the logarithm of this variable.

According to Wooldridge (2001), the 2SLS procedure provides a good estimate of the average effect in a latent variable model where one of the explanatory variables is correlated with the error term. Another important advantage of this procedure is that the estimated coefficients are directly interpretable.

Note that [3] differs from [2] as it includes industry dummies in the model.

As we are using the 2SLS estimator with robust VCE, the Wooldridge’s robust score test of overidentifying restrictions is performed. A significant test statistic could represent either an invalid instruments or an incorrectly specified equation.

References

Asker, J., & Bar-Isaac, H. (2014). Raising retailers’ profits: on vertical practices and the exclusion of rivals. American Economic Review, 104(2), 672–686.

Besanko, D., & Perry, M. K. (1993). Equilibruim incentives for exclusive dealing in a differentiated products oligopoly. Rand Journal of Economics, 24(4), 646–665.

Bonnet, C., Dubois, P. (2010). Inference on vertical contracts between manufacturers and retailers allowing for non linear pricing and resale price maintenance. RAND Journal of Economics, 41, 139–164.

Bonnet, Dubois, C. P., Villas Boas, S. B., & Klapper, D. (2013). Empirical evidence of the role of nonlinear wholesale pricing and vertical restraints on cost pass-through. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 95(2), 500–515.

Comanor, W. S., & Rey, P. (1997). Competition policy towards vertical restraints in the US and Europe. Empirica, 24(1–2), 37–52.

Cooper, J. L., Frowb, D., & O’Brien, M. V. (2005). Vertical antitrust policy as a problem of inference. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 23, 639–664.

Dobson, P., Waterson, M. (1996), Vertical restraints and competition policy. Research Paper 12. Office of Fair Trade. http://www.oft.gov.uk/shared_oft/reports/comp_policy/oft177.pdf.

European Commission (2010). Guidelines on Vertical Restraints, note 9

Gilligan, T. (1986). The competitive effects of resale price maintenance. The Rand Journal of Economics, 17(4), 544–556.

Giovannetti, E., & Magazzini, L. (2013). Resale price maintenance: an empirical analysis of UK firms’ compliance. The Economic Journal, 123, F582–F595.

Jullien, B., & Rey, P. (2007). Resale price maintenance and tacit collusion. The Rand Journal of Economics, 38(4), 983–1001.

Lafontaine, F., & Slade, M. (2005). Exclusive contracts and vertical restraints: empirical evidence and public policy. In P. Buccirossi (Ed.), Handbook of antitrust economics. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Motta, M. (2004). Competition policy: theory and practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rey, P., & Stiglitz, J. (1988). The role of exclusive territories in producer’s competition. Rand Journal of Economics, 26, 431–451.

Rey, P., & Stiglitz, J. (1995). Vertical restraints and producers competition. European Economic Review, 32, 561–568.

Rey, P., & Tirole, J. (1986). The logic of vertical restraints. American Economic Review, 76(5), 921–939.

Rey, P., Vergé, T. (2005), The economics of vertical restraints. In Hanbook of Antritrust Economics, Paolo Buccirossi (ed.), M.I.T. Press.

Rey, P., & Vergè, T. (2010). Resale price maintenance and interlocking relationships. Journal of Industrial Economics, 58, 928–961.

Spengler, J. (1950). Vertical integration and antitrust policy. Journal of Political Economy, 58, 347–352.

Telser, L. (1960). Why should manufacturers want fair trade? Journal of Law and Economics, 86(1960), 86–105.

Wooldridge, J. (2001). Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

I am grateful to Daniel Miles, M. José Moral and Consuelo Pazó and two anonymous referees for their suggestions as well as the comments of the audiences of the XXIII Jornadas de Economía Industrial, XXXI Simposio de Analisis Económico, 35th European Association for Research in Industrial Economics. All errors remain my own responsibility. Financial support from the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation through grant ECO2014-57553 and Xunta de Galicia through grant EM2013/013 is gratefully acknowledged.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

González, X. Empirical Regularities in the Vertical Restraints of Manuacturing Firms. Atl Econ J 43, 181–194 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11293-015-9452-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11293-015-9452-8