Abstract

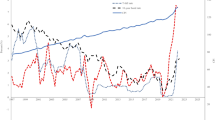

Between August 25, 1939 and June 7, 1940, there was a free market for British pounds in New York. German success at the outset of World War II caused the value of free sterling to fall relative to the official exchange rate. This imposed an externality that made it more difficult for Britain to finance the war. Eventually, the externality became large enough that Britain chose to take extreme measures to abolish it, even at the expense of tarnishing the reputation of London’s financial markets. We collected daily data to investigate how the market reacted to war news and to policy changes. Using methods developed by Bai and Perron (Econometrica 66:47–78, 1998; Journal of Applied Econometrics 18:1–22, 2003), we find 17 breaks in the exchange rate. Fourteen are associated with military events and three are associated with policy changes. The episode illustrates how markets can fail to serve the public interest during times of war.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

It should be noted that the British government took many other steps to improve its financial position. Among other things, during 1940 it requisitioned U.S. securities owned by British residents that could be sold to cover its dollar obligations. See Clayton 1953.

References

Aldcroft, D. H., & Oliver, M. J. (1998). Exchange rate regimes in the twentieth century. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Atkin, J. (2005). The foreign exchange market of London: Developments since 1900. New York: Routledge.

Bai, J., & Perron, P. (1998). Estimating and testing linear models with multiple structural changes. Econometrica, 66, 47–78.

Bai, J., & Perron, P. (2003). Computation and analysis of multiple structural change models. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 18, 1–22.

Balogh, T. (1940). The drift towards a rational foreign exchange policy. Economica, 7, 248–279.

Brown, W. O., Jr., & Burdekin, R. C. K. (2002). German debt traded in London during the second world war: a British perspective on Hitler. Economica, 69, 655–669.

Choudry, T. (2010). World War II events and the Dow Jones industrial index. Journal of Banking & Finance, 34, 1022–31.

Churchill, W. (1930). My early life: A roving commission. New York: Touchstone. 232.

Churchill, W. (1949/1985). Their finest hour (pp. 143–144). Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company.

Clayton, G. (1953). The Development of British Exchange Control 1939–45. Canadian Journal of Economics and Political Science, 19, 161–173.

Economist (1939a). The question of over-valuation. August 26, 408–409.

Economist (1939b). Exchange loopholes. November 11, 217.

Economist (1940a). The free market in sterling. February 24, 337–338.

Economist (1940b). The free market in sterling II. March 2, 381–382.

Economist (1940c). Slump in free sterling rate. March 30, 578.

Economist (1940d). Free and controlled pounds. April 608–609.

Economist (1940e). Pound and dollar. July 20, 71.

Economist (1940f). Exchange control at last. July 20, 93.

Frey, B. S., & Kucher, M. (2000). History as reflected in capital markets: the case of World War II. Journal of Economic History, 60(2), 468–96.

Frey, B. S., & Kucher, M. (2001). Wars and markets: how bond values reflect the Second World War. Economica, 68(271), 317–333.

Frey, B. S., & Waldenström, D. (2004). Markets work in wars: World War II reflected in the Zurich and Stockholm bond markets. Financial History Review, 11(1), 51–67.

Hall, G. J. (2004). Exchange rates and casualties during the First World War. Journal of Monetary Economics, 51(8), 1711–1742.

Higgins, B. H. (1949). Lombard street in war and reconstruction. NBER.

Liu, J., Wu, S., & Zidek, J. V. (1997). On segmented multivariate regressions. Statistica Sinica, 7, 497–525.

Mitchell, W. (1903). A history of the greenbacks. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

New York Times (1939a). British fund holds the pound steady; imports of gold here put at $12,648,000. August 24, 33.

New York Times (1939b). British fund keeps sterling at $4.68 1/8. August 25, 23.

New York Times (1939c). Fund withdraws support of pound, August 26, 6.

New York Times (1939d). News of markets in european cities. September 6, 44.

New York Times (1939e). Treasury to fight sterling “dumping”. September 19, 50.

New York Times (1939f). Hitler tells allies it is his peace or finish fight; Britain and France for war til Hitlerism is ended. September 20, 1.

New York Times (1939g) House dooms arms embargo. 243–181, November 3, 1.

New York Times (1939h). Uruguay lets the Spee stay for repairs as British mass warships off Montevideo.; Finns report gains; League drops Russia. December 15, 1.

New York Times (1940a). Britain weighing war upon Russia. March 11, 1.

New York Times (1940b). Trade deficit up for Great Britain. March 25, 28.

New York Times (1940c). British yield southern Norway to Nazis; evacuate Aandalsnes; Norse fight on; Ships rushed to Alexandria. May 3, 1.

New York Times (1940d). Churchill pledges war till Empire ends. June 5, 1.

New York Times (1940e). Allies are rushing gold to U.S.; $286,720,000 comes in one day. June 5, 1.

New York Times (1940f). Britain tightens curb on sterling. June 8, 23.

New York Times (1940g). Sterling breaks on Italy’s stand. June 11, 39.

New York Time (1940h). Hull warns nazis to keep hands off the pan-American parley in Havana; Massed German Planes Raid Britain. July 12,1.

New York Times (1940i) Deals are moderate here in fixed pound but free sterling is dull and unchanged. July 24, 36.

Phillips, R. J. (1988). ‘War news’ and black market exchange rate deviations from purchasing power parity: wartime South Vietnam. Journal of International Economics, 25, 373–378.

United States Department of Commerce (1939). The depreciation of the pound sterling. Survey of Current Business, November, 11–18.

United States Department of Commerce (1940). The business situation. Survey of Current Business, April, 3–7.

United States Federal Reserve. (1940a). Review of the month—International developments and United States foreign trade: allied control measures. Federal Reserve Bulletin, 26, 377–384.

United States Federal Reserve. (1940b). Review of the month—Treasury financial operations: new British exchange regulations. Federal Reserve Bulletin, 26, 633–638.

Waldenström, D., & Frey, B. S. (2008). Did Nordic countries recognize the gathering storm of World War II? Evidence from the bond markets. Explorations in Economic History, 45(2), 107–126.

Acknowledgments

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kanago, B., McCormick, K. The Dollar-Pound Exchange Rate During the First Nine Months of World War II. Atl Econ J 41, 385–404 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11293-013-9380-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11293-013-9380-4