Abstract

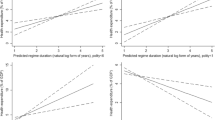

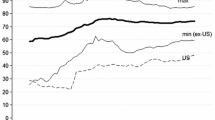

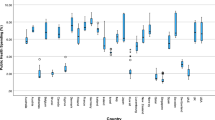

This paper relies on a panel of state-level data to address the socio-economic determinants of AIDS mortality in the United States. We find that male and female AIDS mortality rates are dependent on a number of factors, including per capita income, physician supply, per capita prescription drug expenditure, and race. The role of prescription drug expenditure is found to be sensitive to its level of aggregation, with the absolute value of the prescription drug expenditure elasticity lower when AIDS drug assistance program (ADAP) expenditures are utilized. Also, for the ADAP expenditure regressions, the prescription drug expenditure elasticity is highest in absolute value for males.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In light of the conventional view that women outlive men, coupled with morbidity rates being higher for women, many studies (e.g., Macintyre et al. 1996; Mustard et al. 1998; Crémieux et al. 1999, 2005; Bertakis et al. 2000) address gender differences in health outcomes. An aim of this paper is to assess gender differences in the impacts of health and economic variables as well as socio-demographic variables on AIDS mortality.

Since valid instruments should not explain AIDS mortality and should still be highly correlated with ADAP expenditure (see Murray 2006), a number of procedures were followed to assess the quality of new AIDS cases and the unemployment rate as instrumental variables. First, in the first-stage 2SLS regression of ADAP expenditure on new AIDS cases and the unemployment rate, an F-test supports the joint significance of the regression coefficients, thus suggesting new AIDS cases and the unemployment rate are highly correlated with ADAP expenditure. Second, using new AIDS cases (unemployment rate) as the selected instrument in the first-stage regression, and then including the unemployment rate (new AIDS cases) as an additional regressor in the second-stage regression, the coefficient of the unemployment rate (new AIDS cases) in the second-stage regression was insignificant. This suggests the instrumental variables are not good predictors of AIDS mortality.

To test for differences in the male and female results in Table 2, the data in each of the two sets of specifications were stacked and then a gender dummy variable (i.e., equals 1 if female, 0 if male) was interacted with each of the independent variables in Table 2. A coefficient of a particular interaction term that is found to be significant implies a gender difference in the effect of the associated determinant on AIDS mortality. As indicated in Table 2, we find significant gender differences in the coefficients of aggregate prescription drug expenditure, physicians, and gross state product for the simpler specification given in the first two columns of Table 2. For the specifications in the last two columns of Table 2, the interaction terms are significant for aggregate prescription drug expenditure, gross state product, population density, percent of the population that is Black, and percent of the population between the ages of 25 and 54. Although our analysis does not pinpoint the reasons for gender differences—perhaps the lower variance of female AIDS mortality, as indicated in Table 1, contributes to gender differences—we do nonetheless find evidence of gender differences in the determinants of AIDS mortality.

It is difficult to say why the results differ between Tables 2 and 3. The results could be sensitive to a number of factors, including differences in the prescription drug expenditure measure, differences in the sample size between the two tables, and differences in the time period studied. Similar to Table 2, the data for each set of regressions was stacked, and a gender dummy variable was then interacted to test for gender differences in the effects of the independent variables in Table 3. As indicated in Table 3, we find gender differences in the effects of ADAP expenditure, gross state product, the poverty rate, and the percent of the population that is Black.

References

Berger, M. C., & Messer, J. (2002). Public financing of health expenditures, insurance, and health outcomes. Applied Economics, 34(17), 2105–2113.

Bertakis, K. D., Rahman, A., Helms, L. J., Callahan, E. J., & Robbins, J. A. (2000). Gender differences in the utilization of health care services. Journal of Family Practice, 49(2), 147–152.

Bokhari, F. A., Gai, Y., & Gottret, P. (2007). Government health expenditures and health outcomes. Health Economics, 16(3), 257–273.

Crémieux, P., Ouellette, P., & Pilon, C. (1999). Health care spending as determinants of health outcomes. Health Economics, 8(7), 627–639.

Crémieux, P., Meilleur, M., Ouellette, P., Petit, P., Zelder, M., & Potvin, K. (2005). Public and private pharmaceutical spending as determinants of health outcomes in Canada. Health Economics, 14(2), 107–116.

Dyson, T. (2003). HIV/AIDS and urbanization. Population and Development Review, 29(3), 427–442.

Ettner, S. (1996). New evidence on the relationship between income and health. Journal of Health Economics, 15(1), 67–85.

Grant, E., Lyttle, C., & Weiss, K. (2000). The relation of socioeconomic factors and racial/ethnic differences in US asthma mortality. American Journal of Public Health, 90(12), 1923–1925.

Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation. (2006). AIDS at 25: An Overview of Major Trends in the US Epidemic. Website. http://www.kff.org/hivaids/upload/7525.pdf.

Hitiris, T., & Posnett, J. (1992). The determinants and effects of health expenditure in developed countries. Journal of Health Economics, 11(2), 173–181.

Lichtenberg, F. (2003). The effect of new drug approvals on HIV mortality in the US, 1987–1998. Economics and Human Biology, 1(2), 259–266.

Macintyre, S., Hunt, K., & Sweeting, H. (1996). Gender differences in health: are things really as simple as they seem? Social Science and Medicine, 42(4), 617–624.

McGinnis, K., Fine, M., Sharma, R., Skanderson, M., Wagner, J., Rodriguez-Barradas, M., et al. (2003). Understanding racial disparities in HIV using data from the veterans aging cohort 3-site study and VA administrative data. American Journal of Public Health, 93(10), 1728–1733.

McLaughlin, D., & Stokes, C. (2002). Income inequality and mortality in US counties: does minority racial concentration matter? American Journal of Public Health, 92(1), 99–104.

Mocroft, A., Gill, M. J., Davidson, W., & Phillips, A. N. (2000). Are there gender differencesin starting protease inhibitors, HAART, and disease progression despite equal access to care? Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 24(5), 475–482.

Murray, M. P. (2006). Avoiding invalid instruments and coping with weak instruments. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 20(4), 111–132.

Mustard, C. A., Kaufert, P., Kozyrskyj, A., & Mayer, T. (1998). Sex differences in the use of health care services. New England Journal of Medicine, 338(23), 1678–1683.

Newhouse, J. P. (1977). Medical-care expenditure: a cross-national survey. Journal of Human Resources, 12(1), 115–125.

Palella, F., Jr., Delaney, K., Moorman, A., Loveless, M., Fuhrer, J., Satten, G., et al. (1998). Declining morbidity and mortality among patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus infection. New England Journal of Medicine, 338(13), 853–860.

Poundstone, K. E., Chaisson, R. E., & Moore, R. D. (2001). Differences in HIV disease progression by injection drug use and by sex in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. AIDS, 15(9), 1115–1123.

Richardus, J., & Kunst, A. (2001). Black-white differences in infectious disease mortality in the United States. American Journal of Public Health, 91(8), 1251–1253.

Shi, L., & Starfield, B. (2001). The effect of primary care physician supply and income inequality on mortality among blacks and whites in US metropolitan areas. American Journal of Public Health, 91(8), 1246–1250.

UNAIDS. Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. (2007). AIDS Epidemic Update. Website. http://www.unaids.org.

US Department of Health and Human Resources. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2004). HIV/AIDS Surveillance Report: Cases of HIV Infection and AIDS in the United States, 2004. Website. http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/stats/hasrlink.htm.

Van Sighem, A., Van de Wiel, M., Ghani, A., Jambroes, M., Reiss, P., Gyssens, J., et al. (2003). Mortality and progression to AIDS after starting highly active antiretroviral therapy. AIDS, 17(15), 2227–2236.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gallet, C.A. The Determinants of AIDS Mortality: Evidence from a State-Level Panel. Atl Econ J 37, 425–436 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11293-009-9188-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11293-009-9188-4