Abstract

This paper examines if patent protection and technology transfer facilitate R&D in a sample that includes both developed and emerging countries. A semiparametric model is used to estimate the relevant parameters using country level data from 21 countries, of which six are emerging, for the period 1981–1997. The results suggest thresholds in patent protection and technology transfer: patent protection has a positive effect which weakens at high levels of protection, and FDI has a positive effect only if the country depends heavily on FDI.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Notable papers that discuss the relationship between R&D and productivity growth are Romer (1990), Grossman and Helpman (1991), and Aghion and Howitt (1998), on the theoretical side, and Griliches (1979, 1980), Griliches and Mairesse (1990), and Keller (2002), on the empirical side, to mention a few. In the area of technology transfer and spillovers, recent empirical contributions include Coe and Helpman (1995), Coe, Helpman, and Hoffmaister (1997), van Pottelsberghe de la Potterie and Lichtenberg (2001), and Keller (2002).

We are not aware of any other study that investigates the effect on R&D of patent rights index and technology transfer using a flexible functional form.

We are limited to only six low and medium-income countries due to data constraints.

For Romer, excessive protection impinges on nonrivalry and also creates a monopoly distortion, both of which hurt innovation and growth.

Theoretically, for this to happen it is sufficient that the profit motive rise at a diminishing rate (implied by diminishing productivity) while costs (of innovating and accessing existing technology) rise at an increasing rate.

For a recent study of technology transmission and their effects on productivity see Keller (2002).

van Pottelsberghe de la Potterie and Lichtenberg (2001) are the first to consider outward FDI and its effects on productivity; their sample includes 13 industrialized countries between 1971–1990, and they find outward FDI to be a significant factor in explaining productivity.

The argument being inward FDI crowds out domestic innovative activity.

Manufacturing import is a reasonably good proxy for trade in intermediate goods because it is a key vehicle that enables technology transfer via imitation and emulation.

GDP also proxies for other determinants of R&D, like development of the financial sector which facilitates credit, and availability of complementary institutions, say, research institutes and universities and their quality.

See World Development Indicators (1999) for detailed definitions of the variables used.

One might feel concerned that in every regression we are ignoring nonlinearity in the other regressors and that this leaves some room for misspecification bias. The bias, if any, however, will be much less than the situation where the model is purely linear and parametric.

We also tried slightly higher values than the optimal bandwidth but that did not change the results.

In general, the derivatives are not considered significant in the ranges where the horizontal zero line (implying that the partial effects are zero) passes through the confidence bands.

The issues regarding the possible direction of causality and the lag structure between R&D expenditure and patent count are well known. See for example, Hall, Griliches and Hausman (1986). Using U.S. firm level data they do not find any definite conclusion about the lag structure. Guo and Trivedi (2002) show that the conclusions in Hall et al. (1986) are not quite comprehensive simply because their data suffer from long tail behavior and serious over-dispersion problem. Hence a simple Poisson regression will fail to fit the data. They emphasize using some nonparametric type flexible functional forms to analyze the patent count–R&D relationship. Using flexible functional forms they show that R&D affects patent counts (for U.S. firm level data) with some lag structure although they argue that more research is necessary for a more definite answer. Note that we have continuous data on patent rights index rather than patent count data and also our focus is on the determinants of R&D expenditure and hence our modeling strategy is different. However, given the empirical perplexity regarding the direction of causality as well as about the exact lag structure to be used to analyze the effect of R&D on patent, we plan to conform to the common theoretical belief that patent affects R&D at least in the same period and R&D affects patent at least with some lag.

The plot shows that the zero line always remains below the 5% confidence bands of the estimated partial effects.

We only list countries that have all their observations in this range.

We note that the average value of the coefficient reported here is consistent with the literature suggesting that there is no significant relationship between inward-FDI and R&D. See van Pottelsberghe de la Potterie and Lichtenberg (2001). Of course, the semiparametric framework allows us additional insights – varying coefficients and a threshold.

This list includes only countries that have most of their observations in this particular range. Italy, Spain, Mexico, and Thailand, for example, are not included because some of their observations do not fall in this range.

That R&D undertaken in the leading three countries has no spillover effects on domestic R&D is intriguing. One explanation is that the main sources of technology transfer, FDI and imports, are already accounted for and therefore not much remains to be explained by leading country R&D. Another explanation is that while there are productivity spillovers (see recent papers by Keller, 2002; van Pottelsberghe de la Potterie and Lichtenberg, 2001; Zachariadis, 2004), those do not represent R&D spillovers.

For the quadratic-form significance test, RESET test and the Li et al. (2002) test, lagged values of FDI, import and GDP (real GDP per capita) are used.

In their paper the alternative is a broad smooth coefficient model where the partially linear model is shown to be a special case.

Note that there is no separate constant intercept term in our model (1) because the estimation is based on Taylor series expansion of m(.) which embeds the constant term.

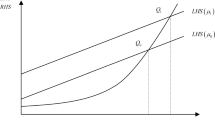

From Fig. 2 also we find that the relationship does not show much curvature or even a significant impact on R&D until FDI reaches a threshold; only at this end segment we observe a sharp turn.

We are thankful to an anonymous referee for drawing our attention to this point.

The imposition of a particular type of nonlinear form, if not correctly determined, may also lead to misspecification problem, and it is almost impossible to be sure about the exact linear/nonlinear specification. Thus the use of a specification free method is a safe strategy.

And we use lagged values of the endogenous variables to address the endogeneity issue.

Lederman and Maloney (2003) also use lagged values of the GDP variable as the instrument in their GMM estimation.

Note that the computed values of FF1 and FF2 test statistics (Pesaran & Taylor, 1999, p. 262) turn out to be 29.48 and 31.54 which reject the null at the 1% level (the test statistic follows a chi-square distribution with one degree of freedom). Thus for our data and variables, a linear GMM framework would have some misspecification bias involved, which would produce biased results without improving efficiency.

In case of nonlinear GMM estimation an analytical solution exists only if the functional form is known and straightforward. However, as is well known it is very difficult to predetermine the specific functional form. In case of a parametric form Y it = f(X it ,Z it ,θ), θ being the parameter vector of the model, one is faced with a nonlinear optimization and the problem pertaining to the choice of initial values of the parameter vector θ remains. Method of simulated moments (MSM) could be used in a GMM framework when an analytical solution is problematic, but that would impose strong distributional assumptions on the data generating process (simulation) and the solutions would not generally be robust to the data generating process itself. See Greene (2003) and Davidson and MacKinnon (2004). Also, using such a method, we would not be able to translate the partial effects (of the variables of interest on the response variable) graphically; that is, the varying dynamics would remain unexplored.

We do not use fixed effect dummies simply because the literature on fixed effect semiparametric regression (under smoothness restriction, which is essential for estimating the partial effects) with continuous dependent variable is not thoroughly developed. The detailed small sample and asymptotic properties of such estimators as well as a Hausman type test to choose between fixed vs. random effect models in such semiparametric framework are yet to be developed. Hence we use OECD group dummy which controls for unobserved group specific heterogeneity effects (OECD vs. emerging countries). The number of emerging countries is quite small in our sample and the OECD countries themselves are always considered to be similar. Thus the country group dummy that we are using should significantly control for the heterogeneity effects.

References

Aghion, P., & Howitt, P. (1998). Endogenous growth theory. Cambridge, MA: MIT.

Cantwell, J. (1989). Technological innovation and multinational corporations. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Caselli, F., & Wilson, D. J. (2004). Importing technology. Journal of Monetary Economics, 51(1), 1–32.

Coe, D. T., & Helpman, E. (1995). International R&D Spillovers. European Economic Review, 39(5), 859–887.

Coe, D. T., Helpman, E., & Hoffmaister, A. W. (1997). North-South R&D Spillovers. The Economic Journal, 107(440), 134–149.

Davidson, R., & MacKinnon, J. G. (2004). Econometric theory and methods. New York: Oxford University Press.

Dunning, J. (1994). Multinational enterprises and the globalization of innovatory capacity. Research Policy, 23(1), 67–88.

Greene, W. H. (2003). Econometric analysis (5th ed.). New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

Griliches, Z. (1979). Issues in assessing the contribution of research and development to productivity growth. Bell Journal of Economics, 10(1), 92–116.

Griliches, Z. (1980). R&D and the productivity slowdown. The American Economic Review, 70(2), 343–348.

Griliches, Z., & Mairesse, J. (1990). R&D and productivity growth: Comparing Japanese and U.S. manufacturing firms. In Charles R. Hulten, (Ed.), National bureau of economic research studies in income and wealth (Vol. 53). Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press.

Grossman, G. M., & Helpman, E. (1991). Innovation and growth in the global economy. Cambridge, MA: MIT.

Guo, J. Q., & Trivedi, P. K. (2002). Flexible parametric models for long tailed patent count distributions. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 64(1), 63–82.

Hall, B. H., Griliches, Z., & Hausman, J. A. (1986). Patents and R&D: Is there a lag? International Economic Review, 27(2), 265–283.

Horstmann, I., Macdonald, J., & Slivinski, A. (1985). Patents as information transfer mechanisms: To patent or (maybe) not to patent. Journal of Political Economy, 93(5), 837–858.

Keller, W. (2002). Trade and the transmission technology. Journal of Economic Growth, 7(1), 5–24.

Lederman, D., & Maloney, W. F. (2003). R&D and development. Policy Research Working Paper 3024, The World Bank.

Li, Q., Huang, C. J., Li, D., & Fu, T. (2002). Semiparametric smooth coefficient models. Journal of Business and Economic Statistics, 20(3), 412–422.

Li, Q., & Stengos, T. (1996). Semiparametric estimation of partially linear regression model. Journal of Econometrics, 71, 207–238.

Li, Q., & Wang, S. (1998). A simple consistent bootstrap test for a parametric regression function. Journal of Econometrics, 87(1), 145–165.

Li, Q., & Wooldridge, J. (2000). Estimating semiparametric econometrics models by local linear method: With an application to cross country growth. Annals of Economics and Finance, 1(2), 337–357.

Mukoyama, T. (2003). Innovation, imitation, and growth with cumulative technology. Journal of Monetary Economics, 50(2), 361–380.

Nadiri, M. I. (1992). U.S. Direct Investment and the Production Structure of the Manufacturing Sector in France, Germany, Japan, and the U.K. New York University and NBER Working Paper, February.

Pagan, A., & Ullah, A. (1999). Nonparametric econometrics. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Papageorgiou, C. (2003). Imitation in non-scale R&D growth model. Economics Letters, 80(3), 287–294.

Park, W. G. (2001). Intellectual property and patent regimes. Economic Freedom of the World, 2001 Annual Report, 101–118.

Perez-Sebastian, F. (1999). Transitional dynamics in an R&D-based growth model with imitation: Comparing its predictions to the data. Journal of Monetary Economics, 45(2), 437–461.

Pesaran, M. H., & Taylor, L. W. (1999). Diagnostics for IV regressions. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 61(2), 255–281.

Robinson, P. M. (1988). Root-N consistent semiparametric regression. Econometrica, 56(4), 931–954.

Romer, P. M. (1990). Endogenous technological change. Journal of Political Economy, 98(5), S17–S102.

van Pottelsberghe de la Potterie, B., & Lichtenberg, F. (2001). Does foreign direct investment transfer technology across borders? The Review of Economics and Statistics, 83(3), 490–497.

UNESCO Institute for Statistics http://www.uis.unesco.org/).

World Development Indicators (1999). The World Bank.

Zachariadis, M. (2004). R&D-induced growth in the OECD? Review of Development Economics, 8(3), 423–439.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Alvi, E., Mukherjee, D. & Eid, A. Do Patent Protection and Technology Transfer Facilitate R&D in Developed and Emerging Countries? A Semiparametric Study. Atl Econ J 35, 217–231 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11293-006-9046-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11293-006-9046-6