Abstract

Objectives

We test the benefit of adding an outreach specialist to a dedicated police team tasked with helping the vulnerable community in the transit system move to treatment or shelter.

Methods

For a year, officer shifts were randomized to determine when they were accompanied by an outreach specialist. One hundred and fifty-eight in-depth treatment conversations regarding treatment or shelter with 165 vulnerable people were assessed for whether they were subsequently transported to a suitable facility.

Results

Likelihood of an individual in a treatment conversation with a specialist and a police officer being transported to a facility was 29% greater than the likelihood for an individual talking with only a police officer; however, this finding was not statistically significant.

Conclusions

With the outcome of getting vulnerable people (mainly people experiencing homelessness) to accept transportation to a shelter or treatment facility, the co-responder model did not significantly outperform the effect of specially trained police officers working independently of the outreach specialist.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Background

The estimated number of people experiencing long-term, chronic homelessness in the United States increased 8.5% between 2018 and 2019 (Henry et al., 2020) and overall homelessness and sheltered homelessness increased from 2020 to 2022 (Sousa et al., 2022). Homelessness frequently co-occurs with health issues, such as behavioral health challenges, or drug and alcohol addiction (Han et al., 2017). Poverty, mental illness, and substance abuse are seen as root causes to homelessness (Forst, 1997), along with structural factors such as declining housing affordability and deinstitutionalization (Laniyonu & Brais, 2023).

People transition to being homeless because of a complex mix of needs and vulnerabilities (Boyle, 2016), but once experiencing residential instability, people are more likely to have involvement with the criminal justice system (Polcin, 2016), and are more likely to die (Leifheit et al., 2021). Safety and security are therefore vital, and the transit environment provides some relief from the weather and relative safety for people experiencing homelessness and conditions related to vulnerability. Those same transit systems, however, are not designed as shelters and struggle to cope with the influx of people who are experiencing residential instability (Berger, 2020) as well as other co-occurring challenges. Passengers, for various reasons, do not feel comfortable around people who are homeless, and this issue has affected all public transit systems, and the larger ones in particular, for at least 30 years (Ryan, 1991). The presence of the vulnerable community leads to issues related to transit service, quality, sanitation, and safety (Ding et al., 2022). Consequently, for a variety of reasons (including improved outcomes for the person, public health, reduced disruption, and improved public perception of the transit system), authorities are examining different policing approaches to the issue. Survey results show that when police deal with unsheltered people in public spaces (such as transit systems), they want officers to provide “helping” solutions and connect people experiencing homelessness to therapeutic services, rather than employ a traditional enforcement approach (Burkhardt & Akins, 2022; Burkhardt et al., 2023).

Various reforms to a traditional approach exist, though most have been applied to situations involving people experiencing behavioral distress rather than homelessness. Many of the goals are similar to those desired by the transit authority in setting up the study reported in this article, including improved crisis de-escalation, increasing individuals’ connection to services, and reducing time spent by officers on calls for service (IACP/UC, 2021). At least in terms of dealing with behavioral health calls, some jurisdictions have explored removing police from the equation all together, such as the Denver (Colorado) Support Team Assistance Response (STAR) mobile crisis response program. A mental health clinician and a paramedic respond to community members experiencing problems related to mental health, poverty, homelessness, or substance abuse challenges. One quasi-experimental study found a reduction in over 1300 criminal offenses in the eight participating police precincts over a 6-month evaluation period (Dee & Pyne, 2022). The similar CAHOOTS (Crisis Assistance Helping Out On The Streets) program in Eugene (Oregon) has been operational for more than 30 years and responds to about 23,000 urgent medical or psychological crisis calls per year (Parafiniuk-Talesnick, 2021).

A second approach is to augment the capacity of police officers, such as through the “crisis intervention team” (CIT) tactic. CIT is a “specialized police-based program intended to enhance police officers’ interactions with individuals with mental illness” (Ellis, 2014: 11). Watson et al. (2017) noted positive officer-level cognitive and attitudinal changes towards people with mental illness or drug dependence. Compton et al. (2014) also report that across a little more than 1000 encounters by 180 officers (91 with CIT training and 89 without), the CIT trained officers were significantly more likely to deploy verbal engagement or negotiation as the highest level of force employed, were less likely to utilize arrest, and were more likely to refer or transport someone to a mental health service.

A third approach is to employ a “co-response” team model (IACP/UC, 2021). Co-response involves “structuring explicit partnerships between police departments and professional mental health practitioners so they can simultaneously respond to incidents involving mental health crises” (Dee & Pyne, 2022: 1). Police and public health agencies have long partnered in practice (Bartkowiak-Théron et al., 2022), though recognition of the role police have in brokering access to public health interventions has only been realized more recently (Wood et al., 2015). Co-responder models involve specially trained police and mental health workers responding to certain types of police calls, often (to use common police call terminology) “emotionally disturbed persons.” The rationale behind a co-responder approach is that “a joint response is preferable as police are specialists in handling situations that involve violence and potential injury while mental health professionals are specialists in providing mental health consultation to officers and mental health care to individuals in crisis” (Shapiro et al., 2015: 607). To date, co-responder models and their associated definitions have focused on pairing “trained police officers with mental health professionals to respond to incidents involving individuals experiencing behavioral health crises” (IACP/UC, 2021: 3, emphasis added) and have not been deployed to address people experiencing homelessness.

A recent analysis of an embedded police social worker model, a co-response that employs a civilian social worker to work alongside police to respond to social calls for service, found that the model demonstrated efficacy by utilizing de-escalation and crisis intervention training on-scene with clients (Ban & Riordan, 2023). Indeed, co-responder programs appear to be an effective approach to connect vulnerable individuals with needed services through follow-up contacts and service treatment referrals (Formica et al., 2022; Shapiro et al., 2015; White & Weisburd, 2018). Furthermore, there is some evidence that individuals experiencing a behavioral health crisis who received response from a co-response team were less likely to be arrested in the short term (Bailey et al., 2022; Lamanna et al., 2018).

In the transit environment, it is acknowledged that transit systems are not designed to be homeless shelters. Bell and colleagues reported that of 46 transit agencies that responded to their survey, 73% believed homelessness impacted their ridership by making others feel uncomfortable, people riding the system as a form of shelter were a nuisance to other passengers, and hostile and disruptive interactions also decreased the number of passengers (Bell et al., 2018). The reactions of customers can include cleanliness of transit facilities, personal hygiene of people who are homeless, and fear and discomfort (Boyle, 2016).

Our article reports efforts by one transit police chief to explore less punitive approaches to people experiencing vulnerable conditions in his transit system (primarily homelessness). The traditional approach to the vulnerable community was to tell them to leave the transit environment (such as a station, train, bus, trolley, or other property controlled by the transit authority) and if they refused, issue a citation or take other enforcement action. The police chief wanted to examine if, rather than simply exclude people from the authority property, an approach could be taken that encouraged people to go to a more suitable triage, treatment, or shelter facility. He created a police-only intervention team but asked us to evaluate whether the introduction of civilian outreach specialists to the team increased the rate at which people experiencing a range of vulnerability issues within the transit system accepted an offer of transportation to a more suitable facility.

It is not clear whether encouraging more people to accept transportation to a suitable facility would address some of the issues with the interaction of the homeless and transit communities, or address overall rates of homelessness within the subway system (given it fluctuates due to a variety of conditions, including weather); however, the study does address one conclusion of a recent review of the literature on co-responder teams that called for more research to “understand program effects on rates of referral to services” (IACP/UC, 2021: 29). Our evaluation responds to this, albeit in regard to predominantly homelessness, and is reported using CONSORT 2010 guidelines (Moher et al., 2010).

Objectives

In this article, we report the result of an experiment to study the addition of outreach specialists to an existing police team tasked with helping people in vulnerable conditions access shelter or treatment. The current literature on the outreach efforts of public transportation agencies and police departments is limited (Ding et al., 2022). It therefore contributes to the literature exploring co-response partnerships in the “gray zone” of interventions that involve police officers but rarely relate to major crimes or the need for formal apprehension (Wood et al., 2017).

Methods

Trial design

The evaluation was designed as a two-group posttest design. Police officers on the existing police team would be accompanied by outreach specialists on certain shifts selected through randomization. Due to administrative limitations and access to the police team, pretest measurements were not possible.

Participants

The participants in this study are vulnerable people whom the police team (with or without an outreach specialist) assessed to be in a crisis of homelessness or another vulnerable situation, and with whom they had a “treatment conversation.” Asquith and Bartkowiak-Théron (2021: 14) define a vulnerable person as “any individual likely to experience harm as a result of their individual, social, or situational contexts, and who is unable to mitigate that harm,” and vulnerability as “any circumstance or condition that is likely to create or exacerbate harm.” Vulnerability can be “transient (like unemployment), permanent (e.g., Down syndrome or autism), incremental (e.g. an escalation of legal or illegal drug use), or cross-sectional (in the case of co-, tri-, or multiple morbidities)” (Bartkowiak-Théron et al., 2022: 4). Most of the people that participated in the study were experiencing homelessness; however, about 20% had other conditions that brought them in contact with the police (detailed later in Table 4).

Patrol officers often encounter vulnerable people throughout their shift, and more often than not will have passing conversations with them. These brief meetings are sometimes classified as contacts or in some cities mere encounters (City of New York Police Department, 2016). These can involve a check on the person’s welfare and perhaps an offer of social service support, but little more than that. They tend to last a few seconds, and if services are declined—as they usually are—culminate in an instruction to leave the transit system.

For the current study, we are interested in more in-depth conversations than mere encounters. Our previous fieldwork with the agency (Ratcliffe & Wight, 2022; Wight & Ratcliffe, 2024) identified that some mere encounters expand into what we term “treatment conversations.” Treatment conversations are more extensive discussions that go beyond just the regular check-in or passing comment of a contact. We define a treatment conversation as “a specific and detailed discussion about entering treatment between a police officer or an outreach specialist, and a person who appears to have specific needs or vulnerabilities.” In practical terms, we found that a good indication that an encounter had morphed into a treatment conversation was if the discussion started to delve into the specific needs of the person, and the officer or outreach specialist was considering, or offered to make, a phone call to a facility to arrange a place or transportation for the person.

We recognize that the distinction between a mere encounter and a treatment conversation might appear vague when described in this way; however, the officers and outreach specialists conveyed to us that they understood the distinction from their experience with the vulnerable community. Fieldwork confirmed that officers appeared to be identifying and recording treatment conversations appropriately.

We left the identification of a person experiencing a vulnerable situation to the officers and outreach specialists. They told us that they would often identify people because they were asleep, lying down, or otherwise on transit property but making no effort to take a bus or subway train. In a number of cases, the person was known to them from previous contact. They contacted people in three main ways, by being:

-

1.

Assigned or accepting a call-for-service from the public through the police dispatch system to attend to a “vulnerable person,”

-

2.

Called by police colleagues to assist with a member of the vulnerable community they had encountered directly while on patrol or through a call-for-service, or

-

3.

While on general patrol in or around transit authority property (mainly subway stations).

Settings and locations

This experiment took place within or near the stations and facilities of the Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority (SEPTA). SEPTA is the public transportation system for the Greater Philadelphia (Pennsylvania) area. SEPTA’s trains, two subway lines, and trolley and bus services support an area of approximately 2200 square miles and comprises the sixth largest transportation system in the United States.

The majority of treatment conversations during the study took place at central Philadelphia train stations (either subway or regional rail), within the interconnecting network of subterranean tunnels in the Center City area of Philadelphia that link Suburban Station, 15th Street Station, and City Hall Station. If we included the street level of JFK Boulevard above these locations, these three sites account for more than 50% of the recorded treatment conversations. Table 1 shows all recorded locations that saw at least 4 treatment conversations.

Two details are relevant. First, the 16th Street and 17th Street junctions with JFK Boulevard are busy public transit intersections with numerous bus stops. Second, there was another project running during this study, and there were a few specific stations the SAVE team were asked to avoid so as to limit cross-project contamination. As a result, Table 1 is more for information than an indication of frequent locations of people experiencing vulnerability conditions. All of these locations are in the Center City area of Philadelphia, which (alongside Kensington) is one of the two main hotspots of medical and public health police calls for service in the city (Ratcliffe, 2021).

Interventions

In late 2020, SEPTA police started developing a small internal unit, comprising two or three officers, called SAVE (Serving A Vulnerable Entity). The objective was to move people sheltering in the transit system into treatment or care facilities, where their underlying needs could be met. The broader goal was to improve conditions within the public transit system. The study ran from June 2022 to June 2023, a period of just over 1 year, and covered a period when SEPTA transit authority entered a year-long contract with a private company to deliver outreach specialists to work alongside the officers. The outreach specialists recruited for the project wore reflective vests (usually labelled “Outreach Navigator”) over civilian clothing. They would patrol the subterranean network of tunnels and station platforms with the uniformed SAVE police officers. At a minimum, the outreach specialists were required to have crisis intervention and CPR training, and instruction on the use of NARCAN® naloxone nasal spray (an opioid overdose treatment). Some had received additional training, such as narcotics awareness and training on helping people experiencing a behavioral health crisis.

Over the year or so of the study, there were just under 12 treatment conversations reported per month (11.85, standard deviation = 8.14), with as few (in a complete month) as 3 and peaking in April 2022 (Table 2).

The intervention involved a member of the SAVE team (either with or without a specialist) having a treatment conversation with a vulnerable person (see definitions in the “Outcomes” and “Participants” sections of this article). It was reported that many treatment conversations lasted up to 5 min (n = 104), while 28 were reported to take between five and 10 min, and 11 took more than 10 min (15 interactions were missing a time estimate). Our fieldwork experience suggests that these time estimates are generally conservative, and many took longer than documented.

No two treatment conversations were the same; however, here are two example scenarios broadly representative of the encounters the authors observed during fieldwork observations. A patrolling team member encountered a man struggling to get up a set of station steps. On speaking to him, it became clear that the man was not only struggling physically, but also mentally. The SAVE team member engaged in a treatment conversation with the man, discussing his needs, and previous experiences with the city’s shelters and facilities. Subsequently, the officer made a phone call to find a suitable space in a shelter facility. The man was offered the place, and the officer drove him to the location in a police car.

In a second example, an officer asked a group of people to move away from a station, because they were not engaged in taking public transport. During this interaction, the officer struck up a conversation with a woman in the group. During this extended conversation, they discussed her drug addiction, her experiences with drug treatment facilities in the city and beyond, and her current situation. The officer offered to make the necessary phone calls to get her accepted into a more suitable treatment facility, but she stated that today was not the day for her, and she wanted to stay with her friends. At that point, she left the station.

If a participant declined assistance, usually the police officer would then explain that the person had to leave the transit authority property, either by taking a train elsewhere (if at a train station) or leaving the station or transit concourse via an exit. Sometimes the officer remained while they left, or the officer left the scene with a promise to return shortly to confirm the person had left the location.

Outcomes

We report the primary outcome, treatment initiation. Treatment initiation occurred when the SAVE police team, or the police officers along with the outreach specialists, successfully concluded a treatment conversation by delivering a vulnerable person, or otherwise arranging for the conveyance of a person, to the care and control of a treatment facility. For this study, a treatment facility is a hospital, intake center, evaluation site, triage clinic, shelter, or other program that has been approved by the SAVE team or outreach provider as a location to which they can transport vulnerable people.

There were no times when a treatment initiation occurred and there were no suitable facilities. This was due to the police officers or outreach specialists often making direct calls to facilities and drawing on personal contacts, or taking a vulnerable person to a triage facility. While the triage facilities we visited on fieldwork were sometimes closed for walk-in clients, they would accept clients delivered by the police team.

The extent of our study ends at treatment initiation because the SAVE team could not control what happens once a person enters a treatment facility, whether they will be successfully enrolled, or whether they will stay for the duration of care. In public health parlance, this distinction exists between “treatment initiation” and “treatment engagement” (Brown et al., 2011). The study was designed with an acceptance of the limitation that treatment engagement was beyond the remit of the transit police department.

Sample size

The participants for this study are drawn from the population of vulnerable people in and around the transit system as encountered by the teams of officers or officers and outreach specialists. Field observations showed the teams had varying degrees of contact with numerous vulnerable persons throughout each shift, ranging from a simple check-in to a treatment conversation; however, to minimize the officer’s already extensive paperwork burden, we were asked to limit the data capture for the officers to only record treatment conversations. The available data therefore reflect all interactions interpreted by the officers as treatment conversations.

Because treatment conversations are organic and emerge as a natural progression of an ongoing encounter between a vulnerable person and the teams, it was not appropriate to sample from the vulnerable community that spends time in the transit system. Of the 158 recorded treatment conversations, they occurred with 165 individuals (we did not include in the individual count two children under the age of two who were with their parents).

Randomization

Sequence generation and allocation concealment

The study was planned for 1 year, with three SAVE officers working 5 shifts each per week. Our initial attempt at randomization was to identify the 30 work shifts every 2 weeks, and then randomly assign outreach specialists to half of those shifts in a 2-week block with a 1:1 random assignment. This randomization schedule was provided to the police department at least 4 weeks before each block, so that they could manage the outreach specialist contract. Because of the need to assist with operational planning, no attempt was made to conceal the sequence. Frequently, due to loss of personnel to other assignments, sickness, vacation, or training, the police officer team was reduced to two, and we adjusted to a 20-shift per 2-week randomization pattern.

Implementation

The first author randomized the schedule using a random number generator in Microsoft Excel and emailed the schedule to the supervising lieutenant at the SEPTA police department. The lieutenant independently consulted with the officers and the outreach specialist contract provider to organize the logistics.

As will be clear from the “Results” section that follows, the randomization was created for an idealized situation where the SAVE officers and specialists were accessible throughout the study period, but this did not manifest in reality. Problems associated with recruiting and retaining outreach specialists meant that officers were sometimes not accompanied on intervention shifts when they should have been, resulting in an imbalance in the eventual count of people contacted by officers alone (104) as compared to contacted for a treatment conversation with an officer/specialist team (61). It was an implementation problem caused by real-world conditions recruiting people to a difficult job involving walking all day, working with the police, and being in a challenging work environment.

Blinding

The experimental assignments were not blinded.

Statistical methods

The study was designed as a posttest-only randomized controlled experiment, also called a prospective cohort design (Morgan et al., 2000; Ratcliffe, 2023; Viera, 2008), though note the subsequent lack of equivalence across treatment and control implementation mentioned above. We report the incidence risk ratio of treatment initiation between police-only and the police/outreach specialist team with 95% confidence intervals (c.i.). The incidence risk ratio is the ratio of the incidence risk of treatment initiation (transport to a facility) by participant in the police and specialist group to the incidence risk of treatment initiation by participant in the police-only group. As recommended by Moher et al. (2010) in the 2010 CONSORT guidelines, we also report absolute effect sizes with risk difference, and the number needed to treat (NTT), which represents the number of treatment conversations required for an outcome to have one additional positive result over the alternative outcome (Kim & Bang, 2020). In the ancillary analyses, we report chi-square values for the treatment conversation interaction and primary outcome by participant race/ethnicity.

Results

Participant flow

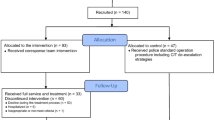

Across the 158 treatment conversations, 165 individuals were contacted. Figure 1 shows that of the 104 participants contacted through a treatment conversion with only officers, 33 (31.7%) were conveyed to a treatment facility. Of the 61 people contacted by the combined team of an officer and specialist, 25 were conveyed to a facility (41%). In only two cases did a person agree to be transferred to a treatment facility or shelter and then subsequently change their mind. In both cases, this change of heart was caused by what the officers referred to as being distracted by an external trigger. Both cases were with only SAVE officers.

Recruitment

Although the study was initially set up with a 1:1 randomization of shifts between officers only and officers with specialists (see the “Randomization” section), the eventual distribution of 165 cases is unbalanced (104 to 61). This lack of equivalence was largely due to staffing issues on the part of the third-party specialist contractor. They experienced considerable turnover during the year of the study, with some specialists staying for only a few days before resigning, or just disappearing and not reappearing. Some staff were diligent, caring, and effective, but others said they were not interested in the role, they did not like working with the police, they found the physical demands of working on foot all day too strenuous, the hours were unappealing, or they were otherwise not suitable for the task. One outreach specialist had to be reported to the police department when they revealed they were (illegally) carrying mace and a handgun during shifts. Another was a diligent and effective worker but was injured when his foot was inadvertently run over by a police vehicle. One SAVE officer who remained on the team for the study’s duration estimated that the officer had worked with at least ten different outreach specialists during the experiment. The result of this was that the likelihood of there being an outreach specialist available for assigned shifts was never guaranteed and fluctuated day-to-day.

Recruitment stopped at the beginning of June 2023 when SEPTA concluded the project and the specialist contract, disbanded the SAVE team, and returned the officers to patrol.

Baseline data

The baseline demographic and characteristics of the 153 individuals for whom race/ethnicity and/or sex were estimated by the officers are shown in Tables 3 and 4. Black males were the predominant group, which reflects a national trend. African Americans comprise about 13% of US population, but about 40% of the homeless population (Sultan, 2020). For reference, as of July 2023, the US Census estimated Philadelphia’s population to be 40.1% Black, 37.1% white, and 15.7% Hispanic (U.S. Census Bureau, 2024).

SAVE officers had an option to report the primary vulnerable condition or conditions pertinent to the treatment conversation, either as perceived by the officer or as indicated by the person experiencing vulnerable circumstances. Table 4 shows that homelessness was overwhelmingly the primary condition encountered, followed by addiction and mental health issues.

Number analyzed

As shown in Fig. 1, two individuals agreed to be transported to a treatment facility but subsequently changed their minds while waiting for transportation. We therefore report (from the last row of boxes in Fig. 1) treatment initiation (transported) versus declined transport, adding the subsequently declined figures to the declined transport count (Table 5).

Outcomes and estimation

The relative risk ratio for treatment initiation (transported to a facility) is 1.29 (c.i. = 0.86, 1.95). The likelihood of an individual in a treatment conversation with a specialist and a police officer being transported to a treatment facility for treatment initiation is 29% greater than the likelihood for an individual in a treatment conversation with only a police officer. In terms of absolute effect size, the risk difference is 9.25 (c.i. = − 5.99, 24.50) while the number needed to treat (NNT) to get one expected additional transportation to a treatment facility is 10.8 (c.i. = 4.08, − 16.69), suggesting that it would take approximately 11 treatment conversations to achieve one additional treatment initiation with specialists compared to SAVE officers working alone. None of the results reported here are statistically significant using 95% confidence intervals (c.i.).

Ancillary analyses

We examined the race/ethnicity of the treatment conversation participants by the type of interaction they had (with either only officers or an outreach specialist with an officer) as shown in the first two numeric columns in Table 6. There were no significant differences between the racial/ethnicity composition of the participants by interaction, X2(df= 3) = 2.525, p = 0.4707 (we should note that every police officer who worked on the SAVE team during the experiment was Black).

We also explored whether there were racial/ethnicity disparities in the primary outcome (Table 6). Differences between the racial/ethnicity composition of the outcome by race were significant, X2(df= 3) = 8.825, p = 0.031; however, this was largely driven by the disparity in the “not recorded” category. When this was omitted from the analysis, the result using just the known race/ethnicity categories was not significant (X2(df= 2) = 1.517, p = 0.468).

Harms

No harms or otherwise unintended effects were reported or observed across any groups.

Discussion

Limitations

Multiple limitations exist. We conducted about 150 h of fieldwork across more than 30 shifts to both ground-check the data capture and answer the officers’ questions about what counted as a treatment conversation. That being said, the data reported here relies on officers’ interpretations of a treatment conversation, and it is possible that they might exclude conversations that participants might consider a specific discussion about entering treatment, and vice versa. As such, we should caveat that the effect of the intervention is also conditional on the police/co-responders initiating a treatment conversation and recording it as such. Second, another study on civilian staff engagement with the vulnerable community was taking place at other stations within the SEPTA system over the course of this research. We were not involved in that study, nor were the SAVE team or the outreach specialists; however, it limited the number of stations that the officers could attend. In general, we understand that the overall goals of both projects were similar, but we recognize that both studies could have had some impact on the other. For example, they might have caused a degree of displacement of people with vulnerable conditions from one location to another. There is therefore the possibility of some contamination across studies, even though the locational boundaries were generally adhered to by SAVE officers and specialists.

A more likely contamination issue is that of learning within the study framework. Over the course of the year, it is possible that the police officers learned skills and knowledge from the specialists that improved their capabilities to enroll people with vulnerabilities into shelter or treatment. We also think it is possible that the reverse could have occurred. One of the SAVE officers had previously been a social worker before joining the police while some of the specialists were new to the role, and from our field observations, relatively inexperienced at dealing with the vulnerable people. Therefore, contamination is a possibility, but the direction is unclear.

An additional caveat is that our outcome measure, treatment initiation, is not a measure of “treatment engagement” (Brown et al., 2011). The study was designed with consideration of the limitations of the transit police department, who could convey a person to a facility, but could not mandate that the person remain there or complete any treatment.

We have already noted that, while this was a randomized experiment, the distribution of treatment conversations was not balanced between the officers and the officers accompanied by treatment conversations. While this results in a lack of balance in the study data, we would contend that this was not caused by any systematic bias introduced by anyone involved in the study. As we noted, it was an exogenous implementation problem caused by recruitment challenges encountered by the third-party outreach contract provider.

A final limitation we would mention is that the indicators of demographics and clinical condition may be as perceived by the officers, rather than reported by the individual participant. We did not ask the officers to indicate the source of the information they reported.

Generalizability

The intervention was implemented in a metropolitan transit system not dissimilar to many urban (largely) subway systems with platforms, ticket areas, and linking tunnel systems. The treatment conversations were not limited to this environment however, so the applicability of an outreach specialist working alongside a police officer to offer support is broadly applicable to a range of situations beyond that of the transit system. The officers were provided with basic and advanced CIT training and de-escalation training, as well as training on mental health issues and recognizing and responding to individuals with special needs. Such training opportunities may not be easily accessible or affordable to some police departments. Access to an outreach provider either through city services or on contract would also be required, though we draw attention to the lack of statistical significance.

Interpretation

The underlying rationale behind the police chief’s initiative was that staff with greater training in handling people experiencing vulnerability would be more able to encourage them to accept referral or transportation to an appropriate public health service, such as was reported by the study of CIT-trained police officers from Compton et al. (2014). From the perspective of the transit authority, this is an output rather than an outcome. A more pertinent outcome would likely be fewer people experiencing homelessness in the transit system. From the perspective of the individual however, just increasing engagement with treatment is arguably a promising outcome. A recent review concluded “the co-responder team model is best labeled as a promising practice in police-behavioral health collaboration for crisis response” (IACP/UC, 2021: emphasis in original). In our study, there was a greater rate of people being transported when engaged by a police officer and an outreach worker, than when approached by a police officer alone. Is this sufficient to consider the intervention a success? If viewed through the lens of process inference, whereby “the null hypothesis is a statement about the data-generating process rather than about a population” (Fotheringham & Brunsdon, 2004: 448), then the process in our study did not produce sufficiently greater numbers of vulnerable people being transported to treatment or shelter to achieve statistical significance.

There are many possible reasons for this. While the rate at which the co-responding team of an officer and an outreach specialist was greater than that of the officers alone, the overall low study n of 165 participants limited our capacity to discern a statistical difference. Second, as Hall (2017: 28) notes, “Each party to the outreach transaction—workers on the one hand and homeless people on the other—has a part to play and a stake in what might (or might very well not) be accomplished.” It is possible that the deciding factor is not who makes the invitation as part of a treatment conversation, but instead the condition of the person experiencing vulnerability at that time, and whether they are ready to accept help.

Our fieldwork confirmed that the job requires compassion, patience, and an extensive understanding of the treatment and shelter system in the city. Many of the people encountered had widespread and repeated involvement with the various shelters and treatment options available and could talk about their benefits, though more often limitations, from personal experience. The work involves not only a social work mindset, but also contextualized local training. The SAVE officers received both a basic and advanced crisis intervention training course and spent time familiarizing themselves with local facilities. In one instance, the lead author accompanied two of the SAVE officers while they introduced their outreach specialists to staff at a local triage facility located within the subway system. This would suggest that there may have been a smaller gulf between the experience and skill set of the officers and the outreach specialists than originally anticipated.

A reviewer of a previous draft of this article asked if SEPTA could just train customer staff members or police officers to have these conversations without the need to hire outreach specialists. Knowledge of the city’s byzantine social support structure appeared necessary, as both outreach specialists and SAVE officers would often make specific calls to individuals in their contact network to arrange suitable facilities for participants. This would suggest that a dedicated team or an extensive training arrangement might be required. Moreover, given the co-morbidity of challenges such as mental health and drug abuse alongside homelessness, there appears a necessity for a specialized function. That being said, the evidence from our research is that while the rate of transportation is greater with the addition of an outreach specialist, this increased rate did not approach statistical significance. The lack of a substantial disparity between the results from the experimental conditions would suggest that officers with sufficient training and experience can adequately fulfil that role to a level approximately commensurate with that of an outreach specialist.

References

Asquith, N. L., & Bartkowiak-Théron, I. (2021). Policing practices and vulnerable people. Springer International Publishing.

Bailey, K., Lowder, E. M., Grommon, E., Rising, S., & Ray, B. R. (2022). Evaluation of a police–mental health co-response team relative to traditional police response in Indianapolis. Psychiatric Services, 73(4), 366–373.

Ban, C. C., & Riordan, J. E. (2023). Re-envisioning public safety through an embedded Police Social Worker (PSW) model: A promising approach for multidisciplinary resource delivery and diversion. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice, 39(4), 537–554.

Bartkowiak-Théron, I., Clover, J., Martin, D., Southby, R. F., & Crofts, N. (2022). Conceptual and practice tensions in LEPH: Public health approaches to policing and police and public health collaborations. In I. Bartkowiak-Théron, J. Clover, D. Martin, R. F. Southby, & N. Crofts (Eds.), Law Enforcement and Public Health: Partners for Community Safety and Wellbeing (pp. 3–13). Springer.

Bell, L., Beltran, G., Berry, E., Calhoun, D., Hankins, T., & Hester, L. (2018). Public transit and social responsibility: Homelessness. Retrieved from Washington, DC. https://www.apta.com/wp-content/uploads/Transit_Responses_Homeless/REPORT-2018-Leadership-APTA-Team-4-Public-Transit-and-Social-Responsibility.pdf. Accessed 30 Jul 2024.

Berger, P. (2020). Transit systems take on role as homeless advocates. Wall Street Journal. Retrieved from https://www.wsj.com/articles/transit-systems-take-on-role-as-homeless-advocates-11577973601

Boyle, D. K. (2016). Transit agency practices in interacting with people who are homeless. The National Academies Press. Retrieved from Washington DC. https://doi.org/10.17226/23450

Brown, C. H., Bennett, M. E., Li, L., & Bellack, A. S. (2011). Predictors of initiation and engagement in substance abuse treatment among individuals with co-occurring serious mental illness and substance use disorders. Addictive Behaviors, 36(5), 439–447.

Burkhardt, B. C., & Akins, S. (2022). How should police respond to homelessness? Results from a survey experiment in Portland, Oregon. Criminal Justice Studies, 35(3), 274–294.

Burkhardt, B. C., Edwards, M., Akins, S., & Stout, C. T. (2023). Understanding public preferences for policing homeless individuals in the United States: Results from a national survey. Deviant Behavior, 44(10), 1462–1479.

City of New York Police Department. (2016). Investigative encounters: Requests for information, common law right of inquiry and level 3 stops. Police Department NYPD.

Compton, M. T., Bakeman, R., Broussard, B., Hankerson-Dyson, D., Husbands, L., Krishan, S.,... Watson, A. C. (2014). The police-based Crisis Intervention Team (CIT) model: II. Effects on level of force and resolution, referral, and arrest. Psychiatric Services, 65(4), 523–529

Dee, T. S., & Pyne, J. (2022). A community response approach to mental health and substance abuse crises reduced crime. Science Advances, 8(eabm2106), 1–9.

Ding, H., Loukaitou-Sideris, A., & Wasserman, J. L. (2022). Homelessness on public transit: A review of problems and responses. Transportation Reviews, 42(2), 134–156.

Ellis, H. A. (2014). Effects of a Crisis Intervention Team (CIT) training program upon police officers before and after crisis intervention team training. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 28(1), 10–16.

Formica, S. W., Reilly, B., Duska, M., Ruiz, S. C., Lagasse, P., Wheeler, M., ... Walley, A. Y. (2022). The Massachusetts Department of Public Health post overdose support team Initiative: A public fealth–centered co-response model for post–overdose outreach. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice, 28(1), S311-S319

Forst, M. L. (Ed.). (1997). The police and the homeless. Charles C. Thomas.

Fotheringham, S. A., & Brunsdon, C. (2004). Some thoughts on inference in the analysis of spatial data. International Journal of Geographical Information Science, 18(5), 447–457.

Hall, T. (2017). Citizenship on the edge: Homeless outreach and the city. In H. Warming & K. Fahnøe (Eds.), Lived Citizenship on the Edge of Society: Rights, Belonging, Intimate Life and Spatiality (pp. 23–44). Springer International Publishing.

Han, B., Compton, W. M., Blanco, C., & Colpe, L. J. (2017). Prevalence, treatment, and unmet treatment needs of US adults with mental health and substance use disorders. Health Affairs, 36(10), 1739–1747. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0584

Henry, M., Watt, R., Mahathey, A., Ouellette, J., & Sitler, A. (2020). The 2019 Annual Homeless Assessment Report (AHAR) to Congress. Retrieved from https://www.huduser.gov/portal/sites/default/files/pdf/2019-AHAR-Part-1.pdf

IACP / UC. (2021). Assessing the impact of co-responder team programs: A review of research. Retrieved from Washington DC: https://www.theiacp.org/sites/default/files/IDD/Review%20of%20Co-Responder%20Team%20Evaluations.pdf

Kim, J., & Bang, H. (2020). Risks in biomedical science - absolute, rRelative, and other measures. Dental Hypotheses, 11(3), 69–71.

Lamanna, D., Shapiro, G. K., Kirst, M., Matheson, F. I., Nakhost, A., & Stergiopoulos, V. (2018). Co-responding police–mental health programmes: Service user experiences and outcomes in a large urban centre. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 27(2), 891–900.

Laniyonu, A., & Brais, H. (2023). Policing of homelessness and opportunities for reform in Montreal. Canadian Journal of Criminology and Criminal Justice, 65(2), 59–77.

Leifheit, K., Chaisson, L., Medina, J., Wahbi, R., & Shover, C. (2021). Elevated mortality among people experiencing homelessness with COVID-19. Open Forum Infectious Diseases, 8(7), ofab301

Moher, D., Hopewell, S., Schulz, K. F., Montori, V., Gøtzsche, P. C., Devereaux, P. J., ... Altman, D. G. (2010). CONSORT 2010 Explanation and Elaboration: Updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. British Medical Journal, 340(c869), 1–28

Morgan, G. A., Gliner, J. A., & Harmon, R. J. (2000). Randomized experimental designs. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 39(8), 1062–1063.

Parafiniuk-Talesnick, T. (2021). In CAHOOTS: How the unlikely pairing of cops and hippies became a national model. Register-Guard. Retrieved from https://www.registerguard.com/story/news/2021/12/10/cahoots-eugene-oregon-unlikely-pairing-cops-and-hippies-became-national-model-crisis-response/6472369001/

Polcin, D. L. (2016). Co-occurring substance abuse and mental health problems among homeless persons: Suggestions for research and practice. Journal of Social Distress and the Homeless, 25(1), 1–10.

Ratcliffe, J. H. (2021). Policing and public health calls for service in Philadelphia. Crime Science, 10(5), 1–6.

Ratcliffe, J. H. (2023). Evidence-based policing: The basics. Routledge.

Ratcliffe, J. H., & Wight, H. (2022). Policing the largest drug market on the eastern seaboard: Officer perspectives on enforcement and community safety. Policing: An International Journal, 45(5), 727–740

Ryan, D. (1991). No Other Place to Go. Mass Transit, 20(3), 16–17.

Shapiro, G. K., Cusi, A., Kirst, M., O’Campo, P., Nakhost, A., & Stergiopoulos, V. (2015). Co-responding police-mental health programs: A review. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 42(5), 606–620.

Sousa, T. D., Andrichik, A., Cuellar, M., Marson, J., Prestera, E., Rush, K., & Abt Associates. (2022). The 2022 annual homeless assessment report (AHAR) to congress. Retrieved from Washington DC. https://www.huduser.gov/portal/sites/default/files/pdf/2022-ahar-part-1.pdf

Sultan, B. (2020). Sharing the solutions: Police partnerships, homelessness, and public health. Community Policing Dispatch (The e-newsletter of the COPS Office), 13(12), 5. Retrieved from https://cops.usdoj.gov/html/dispatch/12-2020/sharing_the_solutions.html

U.S. Census Bureau (2024) Population Estimates, July 1, 2023 (V2023) Philadelphia city, PA [data table]. Quick Facts. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/philadelphiacitypennsylvania/PST045222

Viera, A. J. (2008). Odds ratios and risk ratios: What’s the difference and why does it matter? Southern Medical Journal, 101(7), 730–734.

Watson, A. C., Compton, M. T., & Draine, J. N. (2017). The crisis intervention team (CIT) model: An evidence-based policing practice? Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 35(5–6), 431–441.

White, C., & Weisburd, D. (2018). A co-responder model for policing mental health problems at crime hot spots: Findings from a pilot project. Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice, 12(2), 194–209

Wight, H., & Ratcliffe, J. H. (2024). Aiding or enabling? Officer perspectives on harm reduction and support services in an open-air drug market. Policing and Society, 34(6), 535–550.

Wood, J. D., Taylor, C. J., Groff, E. R., & Ratcliffe, J. H. (2015). Aligning policing and public health promotion: Insights from the world of foot patrol. Police Practice and Research, 16(3), 211–223.

Wood, J. D., Watson, A. C., & Fulambarker, A. J. (2017). The “gray zone” of police work during mental health encounters: Findings from an observational study in Chicago. Police Quarterly, 20(1), 81–105.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank SEPTA Police Chief Thomas Nestel III (retired), SEPTA Police Chief Charles Lawson, Lieutenant Val Trower, and the officers and specialists associated with the SAVE team for their enthusiasm for the project and their support for the authors and the evaluation.

Funding

This project was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Justice (5PNIJ-21-GG-02717-RESS). The views expressed in this article do not necessarily represent the views of the Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority, SEPTA Police Department, the National Institute of Justice, the United States Department of Justice, or the government of the United States.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

The study was approved by Temple University’s Institutional Review Board (protocol 29223), and pre-registered with the Open Science Framework on 31st May 2022.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ratcliffe, J.H., Wight, H. Co-response and homelessness: the SEPTA transit police SAVE experiment. J Exp Criminol (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-024-09634-9

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-024-09634-9