Abstract

Objectives

Investigate how the threat of a possible felony conviction affects defendants’ willingness to accept a plea (WTAP) and whether perceptions of collateral consequences explain this influence.

Methods

We use a nationwide (N=659) vignette experiment which manipulated 1) guilt and 2) plea offer charge reduction (felony or misdemeanor) to determine their effect on WTAP. Respondents were also asked to rank the relative importance of common collateral consequences in their decision to plea (or not).

Results

A felony probation plea offer, relative to a misdemeanor probation offer, was associated with lower WTAP. Perceptions of collateral consequences did not account for this “felony effect” on WTAP.

Conclusions

While people want to avoid the “mark” of a felony conviction, it is not necessarily due to fear of specific collateral consequences; instead, it appears that people want to avoid the stigmatizing label.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Up to one-third of U.S. adults have a criminal record (Goggins & DeBacco, 2022; as cited by The Sentencing Project, n.d., National Conference of State Legislatures, n.d.), as of 2010, 19 million people in the United States (U.S.) were living with a felony conviction (Shannon et al., 2017), and in 2023, approximately one million people were incarcerated in state prisons (Sawyer & Wagner, 2024). Someone with a felony record may experience the direct results of a conviction as well as a bevy of potentially lifelong “collateral consequences” affecting many aspects of their lives such as employment, housing, voting, education, and government benefits (National Inventory of Collateral Consequences of Conviction, n.d.). It is also notable that almost all (approximately 95-98%) criminal records are the result of guilty pleas (Johnson et al., 2016; Smith & MacQueen, 2017) and lately, there has been a renewed interest in understanding elements that prompt criminal defendants to accept guilty pleas. In addition to factors such as the probability of conviction (McAllister & Bregman, 1986; Quickel & Zimmerman, 2019; Tor et al, 2010) and guilt (Bordens, 1984; Dervan & Edkins, 2013; Wilford et al., 2021), plea offer severity is a robust predictor of willingness to accept a plea in vignette studies (Dervan & Edkins, 2013; Lee et al., 2021; Redlich & Shteynberg, 2016; Schneider & Zottoli, 2019; Zottoli et al., 2023).

One frequently used tactic during plea negotiations, which can serve as a significant bargaining chip, is a charge reduction, where the prosecutor offers a lower charge severity (e.g., felony to misdemeanor) in exchange for a guilty plea (Johnson et al, 2016; Hollander-Blumoff, 1997; Zottoli et al, 2016). Specific policy considerations also arise for misdemeanors, as research indicates that plea rates may differ across misdemeanors and felonies (Petersen, 2019), the general severity of a plea offer may be at least partially predicted by extralegal factors (e.g., Kutateladze, Lawson, & Andiloro, 2015), and that misdemeanor plea colloquies are shorter and involve fewer questions assessing validity than felonies (e.g., Dezember et al., 2021). Relatedly, research has also begun to explore how collateral consequences, which are often tied to felony convictions, influence defendants’ willingness to accept a guilty plea (WTAP). Extant research on this topic is sparse, but growing (e.g., Edkins & Dervan, 2018; Malone, 2020) and there is little work evaluating the extent to which the threat of a felony conviction incentivizes accepting a misdemeanor plea. One notable exception indicates that a higher proportion of people indicate they will accept a misdemeanor plea offer than a felony, if a felony is the potential severity at trial (Helm & Reyna, 2017; see also Helm et al., 2018).

Like scholars before us (e.g., Kirk & Wakefield, 2018), we believe that the definition of collateral consequences should be expanded to include other informal costs such as the stigma of a conviction, which may make an applicant unlikely to be hired when they are otherwise legally eligible (Pager, 2003). For instance, a robust literature demonstrates that those with felony convictions face significant discrimination in areas such as employment (e.g., Uggen et el., 2014) and housing (e.g., Evans et al., 2019). There is also an emerging literature showing that people are at least somewhat conscious of the costs attached to criminal convictions and may alter their behavior accordingly (Lee & Brown, 2022; Lindsay, 2022). This aligns with a well-established idea that behavior is influenced by the threat of informal costs triggered by formal sanctioning (Williams & Hawkins, 1986; Nagin & Paternoster, 1994). These informal costs can include the loss of accomplishments or future opportunities (e.g., employment, educational, housing), of valued relationships (family, friends, colleagues), as well as reputation (Williams & Hawkins, 1986). While these costs are well-known to decision-making researchers, what is less understood is how these costs influence defendants during plea negotiations.

Methods

With the present study, we use an experimental survey vignette and a U.S. sample of adults to evaluate how the potential “mark” of a felony may influence WTAP. By keeping the punishment (probation) constant and varying only on the potential for a charge reduction (felony or misdemeanor) plea offer, we isolate this influence. We also ask respondents to rank a series of 10 collateral consequences and explore whether rankings and perceptions of collateral consequences may account for any effect of a felony plea offer. Our research questions are:

-

1.

How does the potential “mark” of a felony conviction (relative to a misdemeanor) impact a defendant’s WTAP?

-

2.

If a “felony effect” is observed, how much do perceptions of collateral consequences explain the effect?

Data

This study utilizes data from a large nationwide sample of U.S. adults who were surveyed about their court perceptions, prior experiences, and WTAP in specific situations.Footnote 1 Data were collected online using Qualtrics’ platform and participants were compensated. Qualtrics has a diverse pool of users recruited through various methods (website intercept recruitment, social media, and targeted email lists, Qualtrics, nd). Qualtrics’ stratified quota sampling procedure is increasingly being used within the field (e.g., Fox et al., 2021; Jaynes et al., 2024; Moule et al., 2022) and was applied here to approximately match sex, household income, and age from 2010 U.S. Census. Black and Hispanic individuals were intentionally oversampled because of the overrepresentation of minorities in the criminal justice system.

In total, 659 individuals completed the survey, with the following self-identified demographics: Black (26%); Hispanic (24%); White (59%); Asian (8%); another race/ethnicity (8%) (categories were not mutually exclusive) (See Table 1). The sample is approximately half male (49%), and 45 years old on average, with a range of 18-83. Household income averaged $50,000 to $69,999 a year. About 12% of the sample reported ever being arrested or convicted of a crime, with 8% reporting a prior plea experience. Thirty-four percent reported having a close friend or family member who was arrested or convicted of a criminal offense.

Methodological design

The study employed an experimental vignette in which factual guilt (guilt vs. innocence) and the potential charge reduction (felony vs misdemeanor) were manipulated in a 2 × 2 fully-crossed factorial design.Footnote 2 Although the potential for a charge reduction is our focus, guilt was manipulated because of its recognized impact on plea decisions and potential to moderate main effects (e.g., Wilford et al., 2021; Zottoli et al., 2016). Our methodology was modeled after prior research (Bordens, 1984; Jaynes et al., 2024; Lee et al., 2021; Tor et al., 2010) and presents a drug possession scenario. An advantage of this scenario is that even largely law-abiding individuals could envision themselves facing this circumstance. Piloting was completed among 43 college students to ensure that the vignette was clear and that people might reasonably foresee themselves in the situation. The first section of this vignette, part (a), was as follows:

Imagine you’ve been traveling on a group trip and you’re on your way back. On the last day of your trip, you all lost track of time and had to rush to pack your bags. Luckily, you all made it to the airport on time and made your flight. When you go to pick up your luggage after your flight lands, you are stopped by a Transportation Security Administration (TSA) officer.

After the officer explains that the luggage x-ray found something suspicious in your bag, they search your luggage and find an unmarked bottle of pills which you do not have a prescription for, which the officer determines are Xanax. You are charged with possession of a controlled substance, which is a felony offense. The maximum sentence for this felony offense is 5 years in prison.

To be guilty of possession in this circumstance, the prosecution must be able to prove that you knew the substance was there.

Within the next section, part (b), we randomly assigned guilt or innocence:

1b (Guilty): You get really stressed out flying and traveling and so your friend gave you a few of their Xanax to help ease your anxiety on the flight and the trip. You knew they were in your bag and you were hoping that they would not be noticed. You know that if you take a drug test, it would show that you did take Xanax recently and you do not have a valid prescription for it. 2b (Innocent): You truly did not know that the bottle was in your bag – it must have gotten mixed up in the frenzy of packing while everyone was rushing to the airport. Your friend has a valid legal prescription that they can show the officers and your friend will take ownership of the bottle and its contents. In addition, you have not used any of this Xanax and know that a drug test would prove it.

Within the final vignette section, part (c), we randomized the potential for a reduced charge in the offer:

A few days later, your attorney calls you and says that the prosecutor has made you an offer of pleading guilty to [c1: a misdemeanor, and being sentenced to misdemeanor probation for 1 year; OR c2: a felony, and being sentenced to felony probation for 1 year]. [c1: Misdemeanor / c2: Felony] probation includes regular meetings with a probation officer, random drug testing, and a misdemeanor conviction on your record.

A felony conviction (which is a possibility if you choose to go to trial)Footnote 3 may legally restrict your rights to public housing, certain jobs, voting, federal benefits (public assistance), fostering or adopting a child, student loans, and jury service. A misdemeanor conviction does not carry these consequences.

Respondents were then asked to indicate the likelihood they would accept the plea offer on a scale from 0% to 100%.

Lastly, respondents were asked to rank how important ten common collateral consequences were to their WTAP decision: 1) The shame or stigma that I would experience; 2) harm to my relationships with my family and friends; 3) harm to my future job opportunities; 4) access to public housing; 5) the right to vote and serve on a jury; 6) rights to federal benefits such as public assistance; 7) parental rights (e.g., to foster or adopt); 8) access to student loans; 9) cost of legal fees; 10) concerns about the experience of incarceration.

To ensure response quality, attention and manipulation checks were included throughout the survey (a total of six). All respondents included in this study passed all attention checks. More information about our survey instrument can be found in the Technical Appendix.

Key variables

Dependent variable: willingness to accept a plea (WTAP)

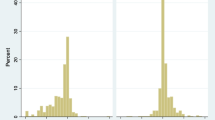

The average WTAP of approximately 42% (see Table 1) suggests that individuals were relatively unlikely to accept the plea offer, on average. Further, Fig. 1 demonstrates that there is substantial variation in WTAP across conditions; the highest WTAP was guilty respondents offered misdemeanor probation (63.55%) and the lowest was innocent respondents offered a felony (20.56%).

Experimental manipulations: felony plea offer & guilt

Given that our conditions were randomized, about half of the sample (51%) received a felony plea offer and the remainder (49%) received a misdemeanor. Similarly, fifty-one percent of the sample received the guilty condition while forty-nine percent received innocent.

Ranked importance of collateral consequences

Post-vignette and WTAP response, each respondent was asked to rank the importance of 10 collateral consequences that may have influenced their WTAP from 1-10. For ease of interpretation, these were reverse coded, such that higher values (e.g., 10) indicate higher importance.

Analytic plan

Across the 4 randomized treatment conditions, no significant differences (p<.05) were observed with respect to sample characteristics such as age, sex, income, risk preference, previous arrest, family arrest, or previous plea experience, indicating successful randomization (see Technical Appendix for more information on these variables). This is also supported by the final cell sizes: misdemeanor/innocent (n=159, 24.13%); misdemeanor/guilty (n=165, 25.04%); felony/innocent (n=164, 24.89%); felony/guilty (n=171, 25.95%). We analyzed our dependent variable using Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression because WTAP is continuous. Our primary analysis focuses on experimental manipulations. However, substantive results are not sensitive to the inclusion of controls (see Technical Appendix).

Results

Within Table 2, Model 1, we assess RQ1. A felony probation plea offer (relative to a misdemeanor) is negatively associated with WTAP, such that those offered a felony plea were about 10.6 percentage points less likely to accept (b=-10.63, p<.001). In addition, consistent with prior research, guilt is positively associated with WTAP such that those who were guilty were approximately 32 percentage points more likely to accept, relative to innocents (b=32.35, p<.001). Within Model 2, Table 2, for methodological reasons, we considered whether a felony offer interacted with guilt and found no evidence of a significant moderating effect.

To assess RQ2, within Table 3, we added the relative rank of each of the collateral consequences into the regression model, as an informal test of confounding. These findings indicate that receiving a felony offer (relative to misdemeanor) (b=-10.37, p<.001) remains significant and there is very little change to the coefficient magnitude. This suggests that the relative rank of these consequences do not explain very much of the “felony effect.” A formal test of confounding, using the KHB method (Karlson et al., 2012), supports this conclusion. While there is a direct effect of felony offer (b=-10.32, p<.01), there is not a significant indirect effect of these collateral consequence rankings (b=-0.27, p=.66). In fact, these rankings cumulatively are only responsible for 2.54% of the “felony effect.”

Discussion and conclusion

Within this study, we sought to contribute to the growing body of literature focusing on individual differences in plea decision-making (Bibas, 2004; Bushway, 2019), with a focus on plea offer charge reductions and collateral consequences. To do this, we used an experimental vignette to evaluate the effect of a felony plea offer on WTAP, while also manipulating guilt. We then explored how rankings of 10 pre-identified collateral consequences may account for any “felony” effect.

With regards to RQ1, being offered a misdemeanor as a form of a charge reduction, as opposed to a felony, increased WTAP, even with the sanction (probation) held constant. While not surprising, this is one of the few known studies where the punishment term was kept constant (see also Helm & Reyna, 2017) and the only difference was whether a felony or misdemeanor conviction would result from accepting an offer. This allowed us to directly quantify the effect of a “felony” conviction as a possibility in plea negotiations. In addition, this effect does not differentially influence innocent and guilty people. This suggests that this type of charge reduction could potentially serve as a tactic for prosecutors to induce pleas during negotiations (Hollander-Blumoff, 1997; Zottoli et al, 2016), which could be problematic if it is used coercively (Redlich et al., 2017; Luna, 2022). Recent work indicating that misdemeanor plea colloquies may be processed more quickly and potentially with less focus on overall plea validity (Dezember et al., 2021) also highlights the importance of understanding how the threat of a felony may influence plea decisions. Further, rankings of collateral consequences were not responsible for our observed “felony effect,” indicating that perceptions of these consequences are not necessarily triggered solely by the potential of a felony conviction, but rather any conviction. These consequences are thus important not only for how they relate to a plea, but rather also as they are connected to potential trial sentences and general engagement with the criminal justice system.

There are some limitations to the present study which also point to key future directions. First, we measured WTAP as a continuous measure from 0-100%, rather than a yes or no. We acknowledge benefits to both approaches and would argue that there is value in gathering a more nuanced measure that captures more sensitivity in decision making (Henderson, Sutherland, & Wilford, 2023; Lee et al., 2021). Along those lines, this research is based on a hypothetical situation and while one would expect there to be a relationship between hypothetical and real-life situations (Beck & Ajzen, 1991; Steiner et al., 2016) and extant literature suggests this to be true (Reyna et al., 2011), it is difficult to know how well these align. We did not directly ask respondents if they could see themselves in this situation or how well they thought the “willingness” measure would translate to actual behavior, and limitation future research should improve upon this. In addition, only 12% of the sample reported a prior arrest or conviction and the decision as to accept or reject a plea offer is likely influenced by prior criminal justice experiences. Future work could build upon the current study by sampling justice-involved populations.

There is also evidence that actual and perceived guilt are not always aligned (Frazier & Gonzales, 2022; Lee et al., 2024) and it is possible that some respondents randomized into the “guilty” condition may not view themselves as such, potentially affecting the validity of these results. Relatedly, evidence strength was not constant across conditions in the present study, likely reflecting true innocence and guilt in “real world” cases (Wilford et al., 2021; Yan et al., 2022). It is thus possible that the lack of a significant interaction between guilt and charge reduction could be related to perceptions of evidence severity; future work should work to disentangle the relative influence of guilt, evidence, and perceptions of conviction likelihood.

In sum, the results of this study demonstrate a significant increase in WTAP associated with the threat of a felony conviction (even with the sanction of probation held constant), and that perceptions of the relative importance of collateral consequences associated with a felony did not explain away this finding. It seems, then, that individuals are not necessarily thinking about specific collateral consequences and are instead focusing on the potential of being a “felon.” In this sense, individuals may simply be aware of the stigma and possible costs associated with a felony without necessarily attaching direct and specific consequences to the threat; people simply want to avoid the label. This points to a potential avenue for pressure on a defendant in the plea bargain process and future research should further investigate the strength of this influence.

Notes

Institutional Review Board approval (000-SB20-147) was gained at the first author’s institution [blinded for review] under expedited review with a waiver of written informed consent.

A priori power analysis in G*power indicated that a sample size of 195 would be sufficient to detect meaningful differences (small effect size=.20) between treatments at p<.05. Thus, our sample size of 659 provides sufficient statistical power.

Text within these parentheses only included for the misdemeanor condition.

References

Beck, L., & Ajzen, I. (1991). Predicting dishonest actions using the theory of planned behavior. Journal of research in personality, 25(3), 285–301.

Bibas, S. (2004). Plea bargaining outside the shadow of the trial. Harvard Law Review, 117(8), 2463–2547.

Bordens, K. S. (1984). The effects of likelihood of conviction, threatened punishment, and assumed role on mock plea-bargaining decisions. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 5(1), 59–74.

Bushway, S. (2019). Defendant decision-making in plea bargains. V., Edkins, A. Redlich,(Eds.), A system of pleas: Social science's contributions to the real legal system, pp. 24-36.

Dervan, L. E., & Edkins, V. A. (2013). The innocent defendant’s dilemma: An innovative empirical study of plea bargaining’s innocence problem. Journal of Criminal Law & Criminology, 103(1), 1–48.

Dezember, A., Luna, S., Woestehoff, S., Stoltz, M., Manley, M., Quas, J. A., & Redlich, A. D. (2021). Plea validity in circuit court: Judicial colloquies in misdemeanor vs. felony charges. Psychology, Crime, and Law, 28, 269–288. https://doi.org/10.1080/1068316X.2021.1905813

Edkins, V. A., & Dervan, L. E. (2018). Freedom now or a future later: Pitting the lasting implications of collateral consequences against pretrial detention in decisions to plead guilty. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 24(2), 204–215.

Evans, D. N., Blount-Hill, K. L., & Cubellis, M. A. (2019). Examining housing discrimination across race, gender and felony history. Housing Studies, 34(5), 761–778.

Fox, B., Moule, R. K., Jr., Jaynes, C. M., & Parry, M. M. (2021). Are the effects of legitimacy and its components invariant? Operationalization and the generality of Sunshine and Tyler’s empowerment hypothesis. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 58(1), 3–40.

Frazier, A., & Gonzales, J. E. (2022). Studying sequential processes of criminal defendant decision-making using a choose-your-own-adventure research paradigm. Psychology, crime & law, 28(9), 883–910.

Goggins, B., & DeBacco, D. A. (2022). Survey of state criminal history information systems, 2020. Bureau of Justice Statistics. https://bjs.ojp.gov/library/publications/survey-state-criminal-history-information-systems-2020. Accessed 10 June 2024.

Helm, R. K., & Reyna, V. F. (2017). Logical but incompetent plea decisions: A new approach to plea bargaining grounded in cognitive theory. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 23, 367–380.

Helm, R. K., Reyna, V. F., Franz, A. A., Novick, R. Z., Dincin, S., & Cort, A. E. (2018). Limitations on the ability to negotiate justice: Attorney perspectives on guilt, innocence, and legal advice in the current plea system. Psychology, Crime, and Law, 24, 915–934.

Henderson, K. S., Sutherland, K. T., & Wilford, M. M. (2023). “Reject the offer”: The asymmetric impact of defense attorneys’ plea recommendations. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 50, 1321–1340.

Hollander-Blumoff, R. (1997). Getting to “guilty”: Plea bargaining as negotiation. Harvard Negotiation Law Review, 2(115), 115–148.

Jaynes, C. M., Lee, J. G., & N. Franks, H. (2024). Evaluating racial and ethnic invariance among the correlates of guilty pleas: A focus on the effect of court legitimacy, attorney type, satisfaction, and plea-offer evaluation. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 61, 335–374. https://doi.org/10.1177/00224278221135544

Johnson, B. D., King, R. D., & Spohn, C. (2016). Sociolegal Approaches to the Study of Guilty Pleas and Prosecution. Annual Review of Law and Social Science, 12(1), 479–495.

Karlson, K. B., Holm, A., & Breen, R. (2012). Comparing regression coefficients between same-sample nested models using logit and probit: A new method. Sociological Methodology, 42(1), 286–313.

Kirk, D. S., & Wakefield, S. (2018). Collateral consequences of punishment: A critical review and path forward. Annual Review of Criminology, 1, 171–194.

Kutateladze, B. L., Lawson, V. Z., & Andiloro, N. R. (2015). Does evidence really matter? An exploratory analysis of the role of evidence in plea bargaining in felony drug cases. Law and Human Behavior, 39(5), 431–442. https://doi.org/10.1037/lhb0000142

Lee, R., & Brown, C. (2022). The relations among career-related self-efficacy, perceived career barriers, and stigma consciousness in men with felony convictions. Psychological Services, 20, 175–183. https://doi.org/10.1037/ser0000646

Lee, J. G., Jaynes, C. M., & Ropp, J. (2021). Satisfaction, legitimacy, and guilty pleas: How perceptions and attorneys affect defendant decision-making. Justice Quarterly, 38(6), 1095–1127.

Lee, J. G., Jaynes, C. M., & Patterson, S. (2024). Whose fault? Defendant perceptions of their own blameworthiness and guilty plea decisions. Journal of Crime and Justice, 47, 241–263.

Lindsay, S. L. (2022). Damned if you do, damned if you don’t: How formerly incarcerated men navigate the labor market with prison credentials. Criminology, 60(3), 455–479.

Luna, S. (2022). Defining coercion: An application in interrogation and plea negotiation contexts. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 28(2), 240–254.

Malone, C. (2020). Plea bargaining and collateral consequences: An experimental analysis. Vanderbilt Law Review, 73(4), 1161–1208.

McAllister, H. A., & Bregman, N. J. (1986). Plea bargaining by defendants: A decision theory approach. The Journal of Social Psychology, 126(1), 105–110.

Moule, R. K., Jr., Burruss, G. W., Jaynes, C. M., Weaver, C., & Fairchild, R. (2022). Concern, Cynicism, and the Coronavirus: Assessing the Influence of Instrumental and Normative Factors on Individual Defiance of COVID-19 Mitigation Guidelines. Crime & Delinquency, 68(8), 1320–1346.

National Conference of State Legislatures. (n.d.). Criminal records and reentry toolkit. https://www.ncsl.org/civil-and-criminal-justice/criminal-records-and-reentry-toolkit. Accessed 10 June 2024.

National Inventory of Collateral Consequences of Conviction. (n.d.). https://niccc.nationalreentryresourcecenter.org/. Accessed 10 June 2024.

Nagin, D. S., & Paternoster, R. (1994). Personal capital and social control: The deterrence implications of a theory of individual differences in criminal offending. Criminology, 32(4), 581–606.

Pager, D. (2003). The mark of a criminal record. American Journal of Sociology, 108(5), 937–975.

Petersen, N. (2019). Low-level, but high speed?: Assessing pretrial detention effects on the timing and content of misdemeanor versus felony guilty pleas. Justice Quarterly, 36(7), 1314–1335. https://doi.org/10.1080/07418825.2019.1639791

Quickel, E. J., & Zimmerman, D. M. (2019). Race, culpability, and defendant plea-bargaining decisions: An experimental simulation. Journal of Forensic Psychology Research and Practice, 19(2), 93–111.

Redlich, A. D., & Shteynberg, R. V. (2016). To plead or not to plead: A comparison of juvenile and adult true and false plea decisions. Law and Human Behavior, 40(6), 611–625.

Redlich, A. D., Bibas, S., Edkins, V. A., & Madon, S. (2017). The psychology of defendant plea decisionmaking. American Psychologist, 72, 339–352.

Reyna, V. F., Estrada, S. M., DeMarinis, J. A., Myers, R. M., Stanisz, J. M., & Mills, B. A. (2011). Neurobiological and memory models of risky decision making in adolescents versus young adults. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 37, 1125–1142. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023943

Sawyer, W., & Wagner, P. (2024). Mass incarceration: The whole pie 2024. Prison Policy Initiative. Retrieved at https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2024.html. Accessed 10 June 2024.

Schneider, R. A., & Zottoli, T. M. (2019). Disentangling the effects of plea discount and potential trial sentence on decisions to plead guilty. Legal and Criminological Psychology, 24, 288–304.

Shannon, S. K. S., Uggen, C., Schnittker, J., et al. (2017). The growth, scope, and spatial distribution of people with felony records in the United States, 1948–2010. Demography, 54, 1795–1818.

Smith, J. Q., & MacQueen, G. R. (2017). Going, going, but not quite gone. Trials continue to decline in federal and state courts. Does it matter? Juridicature, 101, 26–39.

Steiner, P. M., Atzmüller, C., & Su, D. (2016). Designing valid and reliable vignette experiments for survey research: A case study on the fair gender income gap. Journal of Methods and Measurement in the Social Sciences, 7(2), 52–94.

Tor, A., Gazal-Ayal, O., & Garcia, S. M. (2010). Fairness and the willingness to accept plea bargain offers. Journal of Empirical Legal Studies, 7(1), 97–116.

Uggen, C., Vuolo, M., Lageson, S., Ruhland, E., Witham, K., & H. (2014). The edge of stigma: An experimental audit of the effects of low-level criminal records on employment. Criminology, 52(4), 627–654.

Wilford, M. M., Sutherland, K. T., Gonzales, J. E., & Rabinovich, M. (2021). Guilt status influences plea outcomes beyond the shadow-of-the-trial in an interactive simulation of legal procedures. Law and Human Behavior, 45(4), 271–286. https://doi.org/10.1037/lhb0000450

Williams, K. R., & Hawkins, R. (1986). Perceptual research on general deterrence: A critical review. Law & Society Review, 20, 545.

Yan, S., Wilford, M. M., & Ferreira, P. A. (2022). Terms and conditions apply: The effect of probation length and obligation disclosure on true and false guilty pleas. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 20, 457–483. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-022-09543-9

Zottoli, T. M., Winters, G. M., Daftary-Kapur, T., & Hogan, C. (2016). Plea discounts, time pressures, and false-guilty pleas in youth and adults who pleaded guilty to felonies in New York City. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 22(3), 250–259.

Zottoli, T. M., Helm, R. K., Edkins, V. A., & Bixter, M. T. (2023). Developing a model of guilty plea decision-making: Fuzzy-trace theory, gist, and categorical boundaries. Law and Human Behavior, 47, 403–421.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, J.G., Jaynes, C.M. The mark of a felony conviction: How does the threat of a felony influence willingness to accept a plea?. J Exp Criminol (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-024-09626-9

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-024-09626-9