Abstract

Objectives

Test the effects of police compliance with the restrictions on their authority embedded in Social Contract Theory (SCT) on police legitimacy, satisfaction with the police, and willingness to obey police officers.

Methods

A two-stage vignette experiment. In the first, 1356 participants were randomly assigned to one of four study conditions: control, procedural justice (PJ), police performance (PP), and compliance with the social contract (SC). In the follow-up stage, 660 participants were randomly assigned to either a control or proportionality/least restrictive alternative (PL) condition.

Results

Compared to the control condition, the SC manipulation improved evaluations of all three dependent variables. For legitimacy, its effect was no different than that of PJ and PP. For satisfaction, it was similar to that of PP and stronger than the effect of PJ. For willingness to obey, it was no different than the effect of PJ, but stronger than that of PP. The second stage of the experiment revealed that compared to the control condition, the two unique components of the SC model (PL) significantly improved the scores of all three DVs.

Conclusions

Police adherence to the SC, and particularly to its two unique components, is an important determinant of police legitimacy and other outcomes, and should thus be acknowledged by researchers and practitioners. Future research is encouraged to disentangle the relative effects of the “building blocks” making up PJ, PP, and compliance with the SC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The concept of “police legitimacy” needs very little introduction. Since Tom Tyler’s (1990) seminal publication—Why People Obey the Law—thousands of studies across countries, populations, and contexts have assessed how people come to view the police as a legitimate authority, and what the outcomes of police legitimacy are (see reviews by Nagin & Telep, 2017, 2020; Tyler & Nobo, 2023; Weisburd & Majmundar, 2018).Footnote 1 There is no single, agreed upon definition of “police legitimacy” (e.g., Bottoms & Tankebe, 2012); however, as a social-psychological concept, authorities’ legitimacy has been defined as “feelings of obligation and responsibility to defer to authorities” (Tyler & Nobo, 2023: 14). In turn, in the context of policing, “police legitimacy” has often been considered as trust in the police, feelings of obligation to obey police orders, and a sense of moral alignment with the police (e.g., Jackson et al., 2012, 2013; Sunshine & Tyler, 2003; Tyler, 1990, 2006).

The importance of police legitimacy presumably lies in the appealing idea that such feelings of obligation and responsibility can be an important source of compliance and cooperation with law enforcement authorities, as well as of broad law obedience—an idea that received wide empirical support (e.g., Bolger & Walters, 2019; Dai et al., 2011; Desmond et al., 2016; Dickson et al., 2022; Mazerolle et al., 2012; Murphy et al., 2020; Sunshine & Tyler, 2003; Tyler & Fagan, 2008; Tyler & Huo, 2002; Tyler & Jackson, 2014; Walters & Bolger, 2019; Wolfe et al., 2016). Given the promise of police legitimacy, it is not surprising that the antecedents of legitimacy have become an important focus of research. Following early studies in this area (e.g., Sunshine & Tyler, 2003), in trying to identify the antecedents of legitimacy, scholars have focused primarily on concrete assessments regarding the nature of policing, and particularly on the fairness of the processes by which the police exercise their authority (“procedural justice”—PJ) and on instrumental outcomes the police deliver (“police effectiveness” or “police performance”—PP). Both types of assessments were found to be closely linked to legitimacy, while of the two, PJ was usually found to be the primary antecedent of legitimacy (see reviews by Jackson et al., 2015; Mazerolle et al., 2013a; Nagin & Telep, 2017, 2020; Tyler et al., 2015; Weisburd & Majmundar, 2018).

Over time, this general model, in which PJ is assumed to be the primary source of police legitimacy followed by evaluations of PP, has been tested and expanded in numerous ways. For example, scholars have tested its application in different countries (e.g., Factor et al., 2014; Hinds & Murphy, 2007; Reisig & Lloyd, 2009), populations (e.g., Bradford et al., 2014; Murphy & Cherney, 2011; White et al., 2016), and unique contexts or situations (e.g., Gau et al., 2012; Jonathan-Zamir & Weisburd, 2013; Kochel, 2018). One important avenue of research, to which the present study seeks to contribute, concerns other concrete evaluations about police conduct, which do not fall within the “classic,” well-established categorization of PJ versus PP, but may nevertheless impact police legitimacy.

In the present study, we focus on evaluations of police compliance with the “social contract” (SC) as an antecedent of police legitimacy. As detailed below, Social Contract Theory (SCT; Hobbes, Locke, Rousseau; see Wolff, 2023) proposes that prior the establishment of civil society, humankind existed in the highly insecure “state of nature.” Thus, people have chosen to unite and form a compact, in which they give up some of their freedom to the state in return for the provision of safety (e.g., Cohen & Felberg, 1991; Kleinig, 2014). In turn, Kleinig (2014) identifies five constraints on police authority embedded in the SC. Building on Kleinig’s theoretical analysis, Jonathan-Zamir et al. (2023) recently measured public views of the extent to which the police have complied with these constraints in the context of enforcing the COVID-19 regulations, and found that they were “a strong, significant predictor of police legitimacy, independent of the effects of perceived police-provided procedural justice, police effectiveness, contact with the police in the past year, and numerous socio-demographic and other personal characteristics” (p. 12). Nevertheless, it is unclear if citizens’ views regarding police compliance with the SC will show similar effects on police legitimacy if measured in general terms. Moreover, Jonathan-Zamir et al. (2023) relied on data from a single survey. Thus, their analysis is cross-sectional and as such cannot determine causality.

We take the next step in exploring public views of police compliance with the SC as an antecedent of police legitimacy, as well as of satisfaction with the police and of willingness to obey officers. We do so while operationalizing police compliance with the SC in general terms, and using a research design that enables the determination of causality—a true experiment in which participants are randomly assigned to conditions. We begin with a review of the well-known antecedents of police legitimacy (PJ and PP). We then argue for the importance of taking a broad approach when investigating the predictors of legitimacy, and describe SCT and its application to police responsibilities and obligations. We review the study by Jonathan-Zamir et al. (2023), which has taken the first step in examining the link between public assessments of police compliance with the SC and police legitimacy, and the ways by which the present study advances this line of research. We continue with a description of our methodology—a two-stage vignette experiment. The first stage included three manipulations: police-provided PJ, effective PP, and police compliance with the restrictions on their authority dictated by the SC. The second, follow-up stage included a fourth manipulation centered on the two unique requirements from the police embedded in SCT: proportionality between the crime and the response, and applying the least restrictive alternative. We present our findings, which reveal important effects for compliance with the SC on all three dependent variables, and discuss the implications of these findings for future research, policy, and practice.

The antecedents of police legitimacy

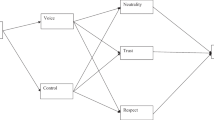

A key question occupying policing scholars in recent decades concerns the roots of police legitimacy, or, in other words, the question of how citizens come to view the police as a legitimate authority. As noted above, perceiving the police as legitimate is considered a highly important goal in democratic societies, due to its expected positive impact on socially desirable outcomes, including willingness to cooperate with the police, comply with their directives, and even obey the law in citizens’ daily lives (see review by Tyler & Nobo, 2023). The primary focus in this body of work has been on PJ, a concept that developed from the social-psychology literature (Leventhal, 1980; Lind & Tyler, 1988; Thibaut & Walker, 1975; Tyler et al., 1997) and captures the extent to which the processes by which authorities engage with the public are perceived to be fair. In formulating their views of the fairness of authorities’ processes, people were found to consider four types of assessments: two concerning the fairness of the decision-making processes and two about the nature of the interpersonal treatment delivered by the authorities (Blader & Tyler, 2003).

In terms of the decision-making process, the first consideration is participation, or voice—people perceive the process as fairer when they are given the opportunity to express their views and tell their side of the story before decisions about their case are made. Second, people like to be treated with neutrality, that is, in an unbiased manner, in which decisions are based only on the facts of the case, not on preconceived attitudes or prejudice. Neutrality is presumably expressed in transparent decision-making processes, which give officers the opportunity to demonstrate that their decisions were indeed based on facts. In terms of interpersonal treatment, the first consideration relates to dignity and respect. People appreciate being treated with politeness and courtesy, and having their rights acknowledged and respected. Finally, people look for evidence suggesting that authorities are acting out of the “right” motivation (trustworthy motives)—true intention to help people and promote the well-being of the individuals involved as well as society at large (e.g., Jonathan-Zamir et al., 2015; Schulhofer et al., 2011; Sunshine & Tyler, 2003; Tyler, 2004, 2009).

Evaluations of police-provided PJ, which in essence have to do with the how, have often been contrasted with more instrumental considerations about the police, which are about the what. These include, for example, views concerning police effectiveness in fighting crime, sufficient presence, and quick responses (e.g., Sunshine & Tyler, 2003). Of the two, the process-related considerations (PJ) were usually found to be more closely correlated with police legitimacy, although evaluations of PP were also found to be a significant predictor of legitimacy (see reviews by Jackson et al., 2015; Mazerolle et al., 2013a; Nagin & Telep, 2017, 2020; Tyler et al., 2015; Weisburd & Majmundar, 2018). Why does the how overtake the what? The importance of fair processes presumably lies in matters of social identify and self-worth: the four types of behaviors that make up PJ signal to the individual that she/he are members of a valued group (inclusion) and have status within that group (standing). These messages, in turn, facilitate high self-esteem, which is a psychologically powerful motivation (Lind & Tyler, 1988; Tyler & Blader, 2000; Tyler & Lind, 1992; see review by Tyler & Nobo, 2023).

While most research on the antecedents of police legitimacy and its expected outcomes focuses on concrete evaluations of the police that reflect PJ or PP (e.g., Nagin & Telep, 2017; Weisburd & Majmundar, 2018),Footnote 2 it has also been recognized that there may be other types of views about police conduct, which do not reflect procedural fairness nor effectiveness, but may nevertheless have significant impact on legitimacy (e.g., Bottoms & Tankebe, 2012; Huq et al., 2017; Tyler et al., 2014). One example is the work by Trinkner et al. (2018) on “bounded authority.” Taking the legal socialization perspective, these researchers have argued that beyond the two broad considerations embedded in PJ—high-quality interpersonal treatment and appropriate decision-making processes—people also care about the extent to which the police are acting within the rightful limits of their power in terms of “when, where, and what power is exercised” (p. 281). Using a nationally representative sample of US adults, Trinkner et al. (2018) found that concerns about the boundaries of police authority significantly contributed to a measure of “appropriate police behavior,” which, in turn, was positively correlated with police legitimacy. As detailed in the next section, in the present study, we test the effects of yet another type of evaluation people may hold about the police—the extent to which they are complying with the SC.

Social Contract Theory and police legitimacy

In the present study, we build on and expand the work carried out by Jonathan-Zamir et al. (2023), where the idea of treating police compliance with the SC as an antecedent of police legitimacy was first presented and tested. The concept of the SC is a philosophical one (Locke, 1690/1980). It suggests that humankind chose to form a civil society in order to avoid the highly insecure “state of nature,” in which individuals had no choice but to protect their life, liberty, and property on their own. In forming a society, people “agreed” to give up some of their natural freedom in return for state-provided protection (e.g., Cohen & Feldberg, 1991; Lawson, 1990).

Clearly, the police are an inherent part of this “contract” between the state and its citizens, as they are the social institution that executes the commitment of the state to provide protection in terms of crime and disorder. Nevertheless, the authority granted to the police in this “contract” is not unlimited. Through a theoretical/philosophical analysis, Kleinig (2014) identifies five main constraints on the authority granted to the police in the SC (for full theoretical justification, see Kleinig, 2014): (1) Police authority should be exercised while showing citizens dignity and respect; (2) The restrictive authority employed by the police should be proportionate to the crime; (3) The least restrictive alternative that can effectively deal with the threat should be applied; (4) The coercive authority used by the police should, in all likelihood, be effective in achieving its goals; (5) The coercive authority should be applied in good faith, with the honest intention of promoting society’s well-being. Kleinig’s (2014) analysis proved invaluable in turning a philosophical idea into empirical analyses, as it set the stage for measuring the extent to which people believe the police are complying with these five constraints, or, in other words, meeting the terms of the SC in their work. In turn, the effects of these views on police legitimacy can be measured.

Importantly, as identified by Jonathan-Zamir et al. (2023), there is obvious overlap between some of these constraints on police authority and the “classic” predictors of police legitimacy: both the concept of PJ and the constraints on police authority embedded in the SC model include the requirement to treat citizens with dignity and respect, and the obligation to exercise coercive authority with the sole purpose of fostering society’s well-being. Moreover, the fourth constraint noted above resembles the concept of PP, which, as reviewed earlier, was also identified as an important antecedent of police legitimacy. Nevertheless, the five requirements from the police dictated by the SC include two unique issues which, to date, received little attention as antecedents of police legitimacy: the expectation for proportionality between the crime and the coercive authority applied in response, and using only the minimum level of coercive authority needed to deal with the problem, even if a more severe response could be justified given the nature of the threat. Moreover, the whole may be greater than the sum of its parts: the “fusion” of considerations making up PJ, for example, may have different effects on police legitimacy than the “fusion” making up police compliance with the SC, despite the shared components. Thus, there appears to be solid justification for an examination of the effects of perceived police compliance with the SC on police legitimacy.

Following this logic, Jonathan-Zamir et al. (2023) tested the role of police compliance with the SC as an antecedent of police legitimacy. These researchers operationalized evaluations of police compliance with the SC in the context of enforcing the COVID-19 regulations, and using survey data from a sample of ~ 1000 Israeli adults and an OLS regression model predicted police legitimacy. Their model revealed a significant association between evaluations of compliance with the SC and legitimacy, after controlling for evaluations of PJ, police effectiveness, and various background characteristics, including experience in policing and having had a positive/negative encounter with the police in the past year. Police compliance with the SC was the second-strongest predictor in the model, surpassed only by PJ.

Nevertheless, important questions remain. First, it is unclear if evaluations of police compliance with the SC will have similar effects if operationalized in general terms rather than in the specific context of enforcing the COVID-19 regulations. Moreover, the study by Jonathan-Zamir et al. (2023) is cross-sectional. While many studies in this area follow this approach, it has been criticized for being inappropriate for identifying causal relationships (see Nagin & Telep, 2017, 2020; Weisburd & Majmundar, 2018). Thus, the analysis by Jonathan-Zamir and colleagues cannot determine whether public evaluations of police compliance with the SC produce legitimacy or are simply correlated with it.

In the present study, we take this line of research forward. We do so in several ways: first, we measure public evaluations of police compliance with the SC in general terms, similar to the way evaluations of PJ and PP are typically measured. Second, we use a research design that enables drawing conclusions regarding causal relationships—a vignette experiment with random allocation into study conditions (for a recent systematic review of experimental vignettes in the study of police PJ, see Nivette et al., 2022). Third, we test the effects of police compliance with the SC not only on legitimacy, but also on two expected outcomes of PJ and/or legitimacy—satisfaction with police handling of the situation (e.g., Gau et al., 2012; Kochel, 2012; Reisig & Parks, 2000; Thibaut & Walker, 1975; Weisburd et al., 2022a; Weitzer & Tuch, 2002) and willingness to obey the officers’ directives (Dickson et al., 2022; Sunshine & Tyler, 2003; Tyler & Fagan, 2008; Tyler & Huo, 2002; Tyler & Jackson, 2014; Walters & Bolger, 2019). More generally, we add to the growing body of work testing the legitimacy model while using research designs that are suitable for identifying causal relationships (e.g., Mazerolle et al., 2013b; Weisburd et al., 2022b; also see systematic review by Nivette et al., 2022).

Stage I: method

In the present study, we have carried out a two-stage vignette survey experiment designed by the authors and carried out using the services of “Midgam Project Web Panel (MPWP),”Footnote 3 a web panel frequently used by social scientists in Israel (e.g., Gubler et al., 2015; Jonathan-Zamir et al., 2023; Perry & Jonathan-Zamir, 2020; Perry et al., 2022; Schori-Eyal et al., 2015). The panel includes nearly 100,000 panelists who participate in different tasks for a fee, and in this sense resembles the US-based MTurk. MPWP panelists are recruited through search engines and sites that refer visitors to MPWP, as well as through other panelists. For any particular study, MPWP samples using the method of stratified sampling by gender and age groups, based on data reported by the Israel Central Bureau of Statistics.

Participants

After excluding 378 panelists who failed the attention check (see below) and 253 panelists who failed to complete the questionnaire, we received from MPWP 1600 complete questionnaires (400 participants per condition). From this sample, we further excluded participants who completed the survey within less than 6 min (7.9%), or who took 29 min or more to complete it (7.3%). These thresholds were determined based on natural breaking points in the distribution of response times, as well as on our assessment that the questionnaire requires at least 6 min to complete with due diligence. On the other hand, those who took too long (in all likelihood due to not completing the survey at one time) may well have forgotten the details of the vignette by the end of the questionnaire (see Curran, 2016). This filtering process left us with a final sample 1356 participants, divided about equally among the study conditions (control condition N = 331; performance condition N = 340; SC condition N = 349; PJ condition N = 336). The characteristics of the sample are presented in Table 1. As can be expected given the random allocation (see below), balance tests (using Chi-square tests for independence; see Appendix 1 - Table 7) revealed that there are no statistically significant differences among the four study conditions in any of the personal characteristics measured, including proxies for prior attitudes toward the police (e.g., level of religiosity, prior contact with the police, and experience in policing; see discussion of placebo attributes in Nivette et al., 2022).

Procedure and instrument

The vignette survey took place between September 4 and 11, 2023. The questionnaire began with a standard consent form approved by the researchers’ departmental ethics committee, informing the participants of the identity of the researchers, the general topic of the survey, the estimated completion time, and the fact that it is anonymous and voluntary. Then, participants were randomly assigned by the online system to one of the four study conditions. In all conditions, participants received a vignette designed as a newspaper article and were told that it is based on a news item published several weeks ago in one of the local newspapers in Israel (which was indeed the case). The procedure of reading a news item was chosen because it is a standard, daily activity. It was thus expected that the participants would find it easy to relate to and reliable. The article described a local event in which police officers sought to catch “beach thieves” who attempted to steal personal belongings from young people hanging out at the beach. This context was selected because of its relevance to many citizens during the summer in Israel, and because of its “neutrality”: it was not expected to generate strong emotional reactions (unlike scenarios involving extreme violence, sexual assaults, or crimes against children), nor relate to a politically sensitive matter (unlike police responses to political violence, terrorist attacks, or protest events).

In the control condition, the event was described in very concrete terms—just the facts. No reference was made to the extent to which the police were effective or fair, for example. A control (“business as usual”) condition allowed us to measure the effect of each manipulation on its own, not just in comparison to the other manipulations. In doing so, we follow the recommendation of Nivette et al. (2022), who conducted a systematic review of studies that used experimental vignettes for investigating police PJ and criticized the frequent comparison of two extremes (e.g., “respect” versus “disrespect”) without a “neutral” condition.

In the PJ condition, the four constituent elements of the PJ model were emphasized. This was expressed in what the officers told the reporter about the event (e.g., “It was important for us to catch the thieves, but to do so in a fair and dignified manner…”), in witnesses’ accounts (e.g., “After the officers caught the thieves, I heard that they asked them what had happened and let them tell their side [of the story].”), and in the general concluding statement of the police department (e.g., “…and officers work over the summer to allow a pleasant and safe swimming season for all.”).

In a similar fashion, the PP vignette emphasized instrumental, performance-oriented features, including the effectiveness of the method used by the officers (e.g., “Immediately I jumped on him and caught him.”), the swift response (e.g., “A quick response is the name of the game.”), and sufficient police presence (e.g., “I really have seen a lot of police around here lately.”). Finally, the SC vignette emphasized compliance with the five constraints on police authority embedded in SCT (e.g., “They also did not exaggerate the force they used and they brought just one police car so there was not too much of a fuss.”). Elements that are part of more than one theoretical construct and thus appeared in more than one vignette (e.g., expressions of “dignity and respect” and “trustworthy motives” appeared in both the PJ and SC condition) were operationalized exactly the same in the different vignettes (for a summary of the components making up each condition, see Table 2; for full vignettes, see Appendix 2).

After reading the vignette, participants were presented with a single multiple-choice question asking what the news item was about (attention check). Those who failed to identify the correct option (“a specific event of capturing property offenders by Israel Police officers”) were informed that they cannot proceed with the study. Participants who answered correctly were presented with statements about the event described in the article, which they were asked to rank according to their level of agreement (1 = “strongly disagree” to 5 = “strongly agree”). Participants were also given the option to skip any survey item by ticking a “don’t know/irrelevant” response.

The first set of survey items, intended for manipulation checks, included statements about the officers’ behavior in terms of PJ, effectiveness, and compliance with the SC, such as “The officers in the article acted out of true intention to benefit the public” (“trustworthy motives,” which was expected to be higher in both the PJ and SC conditions); “The officers in the article used a technique that really brings results” (“effectiveness,” which was expected to be higher in both the PP and SC conditions); and “The officers in the article gave all sides the chance to tell their side [of the story]” (“participation,” which was expected to be higher in the PJ condition). The second set of survey items sought to measure the main dependent variables (DVs), and accordingly included statements that capture the officers’ legitimacy (e.g., “The officers in the article earned my trust”), satisfaction with the officers’ response (e.g., “In my view, the officers in the article made the right decisions”), and willingness to obey the officers (e.g., “If I was present at the event described in the article, I would have ignored the officers’ directives”). All survey items were designed based on the vast literature reviewed above. The questionnaire also included a third set of survey items unrelated to the vignettes, which is not included in the present analysis.

Measures

Three indices were constructed for the manipulation checks: a “PJ judgments” index (M = 3.96, SD = 0.83, range 1.22–5.00, Cronbach’s alpha = 0.88), an “Effectiveness judgments” index (M = 4.54, SD = 0.64, range 1.00–5.00, Cronbach’s alpha = 0.87), and a “Compliance with the SC judgments” index (M = 4.32, SD = 0.56, range 1.58–5.00, Cronbach’s alpha = 0.84). The indices were created by averaging the theoretically relevant survey items. Because of the overlap in some theoretical constructs (e.g., “dignity and respect” is part of both PJ and police compliance with the SC; see above), several survey items were used to construct more than one index (see Table 3 for full list of survey items included in each index).

Similarly, three indices were constructed for the main DVs: the perceived legitimacy of the officers (“Legitimacy index,” M = 4.22, SD = 0.76, range 1.00–5.00, Cronbach’s alpha = 0.79), satisfaction with the way the officers handled the encounter (“Satisfaction index,” M = 4.32, SD = 0.78, range 1.00–5.00, Cronbach’s alpha = 0.83), and willingness to obey the officers (“Willingness to obey index,” M = 4.57, SD = 0.67, range 1.00–5.00, Spearman’s rho = 0.47, p < 0.001). The specific survey items making up each of these indices are reported in Table 4. Finally, binary variables were created for each of the four study conditions (1 = yes, 0 = no), which are the main independent variables (IVs).

Stage I: analyses and results

Manipulation checks

Three ordinary least squares (OLS) regression models were fitted to the data (with the conditions as IVs and the control condition as the reference category) to examine if the way the police handled the situation in the different conditions was perceived by the participants as intended: more procedurally just in the PJ condition, more effective in the PP condition, and more compliant with the SC in the SC condition. Table 5 reveals that, as expected, average PJ judgments were higher in the PJ condition than in the control condition (by 1.16 points on a 1–5 scale). It should be noted that they were also higher in the SC condition, however to a much smaller degree (by 0.38 points). Interestingly, these evaluations were lower in the PP condition compared to the control condition. With regard to judgments of police effectiveness, as expected, they were higher on average in the PP condition compared to the control condition (by 0.49 points). Notably, they were also higher to a smaller degree in the SC condition (by 0.42 points) and in the PJ condition (by 0.30 points). Finally, evaluations of police compliance with the SC were significantly higher in the SC condition (by 0.46 points) than in the control condition. They were also higher to a smaller degree in the PJ condition (by 0.41 points) and in the PP condition (by 0.11 points).

As reviewed earlier, there is a partial overlap between the SC and PJ models, and between the SC and PP models. These overlaps may explain the higher scores in PJ judgments in the SC condition (compared to control), the higher scores in evaluations of police compliance with the SC in the PJ condition (compared to control), and the higher scores in effectiveness judgments in the SC condition (compared to control). It is interesting, however, that effectiveness judgments showed higher scores in the PJ condition compared to the control condition, although the PJ vignette did not include indicators of effectiveness. This may be the outcome of a halo effect (Nisbett and Wilson, 1977; Thorndike, 1920), i.e., a sense that if the police are fair than they must also be effective. Whatever the case may be, our manipulation checks indicate that respondents were able to recognize the different policing styles described in the vignettes. Relative to the control condition, the largest gap in the average level of PJ judgments was found in the PJ condition, the largest gap in evaluations of police effectiveness was found in the PP condition, and the largest gap in evaluations of police compliance with the SC was found in the SC condition.

Multivariate regression models testing the main effects

To examine the effects of the three manipulations (procedurally just policing, performance-oriented policing; social contract-focused policing) on the three main outcomes of interest (evaluations of the officers’ legitimacy, satisfaction with the officers’ handling of the situation, willingness to obey the officers), three ordinary least squares (OLS) regression models were fitted (with the conditions as IVs and the control condition as the reference category). Since no statistically significant differences among the groups were found for any of the participants’ socio-demographic/background characteristics (see Appendix 1 - Table 7), the models do not control for these variables.

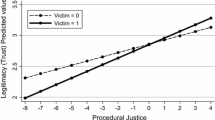

As can be seen from Table 6, the first model reveals that compared to the control condition, all study manipulations show significantly higher assessments of the officers’ legitimacy. Procedurally just policing led to legitimacy scores that were higher by 0.25 points (on a 1–5 scale). Policing that complies with the SC led to legitimacy scores that were higher by 0.20 points, and finally, policing that emphasizes high performance led to legitimacy scores that were higher by 0.15 points. None of the differences between the coefficients was statistically significant, indicating that all three models of police behavior do equally well in promoting legitimacy.

Satisfaction with the way the officers handled the situation was also significantly higher in all three conditions than in the control condition. Here, the largest effect was found for the SC (0.39 points difference) and the PP (0.36 points difference) conditions, with no statistically significant difference between them. At the same time, both conditions showed a significantly larger effect than that of the PJ manipulation (p < 0.05), which showed a difference of only 0.24 points compared to the control condition on the satisfaction index. Finally, willingness to obey the officers showed statistically significant higher scores in both the PJ (0.14 points difference) and SC (0.13 points difference) condition (with no significant difference between them). The PP manipulation showed no statistically significant effect on willingness to obey the officers. Thus, overall, policing that complies with the SC appears to be doing just as well (and at times better) than the two well-known models of PJ and PP in promoting the socially desirable outcomes captured by our DVs.

Stage II: method

The findings of the first stage of the experiment revealed potentially important effects for evaluations of police compliance with the SC on all three DVs. At the same time, given the overlap between the SC model and the PJ model, as well as between the SC model and the notion of police effectiveness (captured in the PP condition), it was unclear if the effects of the SC manipulation are not simply the outcome of the PJ and effectiveness components embedded in it. Thus, we sought to examine the unique effects of the components of the SC model that do not overlap with PJ nor with police effectiveness: proportionality between the crime and the response, and applying only the minimum level of coercive authority necessary to handle the situation. The method of the second stage of the experiment was identical to the first, albeit with only two conditions: an identical control condition, and a “proportionality/least restrictive alternative” (PL) condition.

Participants

Participants for the second stage of the experiment were sampled by MPWP as if this was a new study; however, panelists who participated in stage I (even if excluded in the filtering process) were not approached. MPWP again excluded panelists who failed the attention check (N = 112) or did not complete the survey (N = 139), after which we received 799 valid questionnaires. Similar to the first stage, we examined the distribution of response times, and chose to exclude participants who completed the survey within less than 4 min (10.1%) or above 14 min (7.3%). The cutoff points are different from those determined in the first stage, because in the second stage, the questionnaire was shorter—it did not include the third section, which, as noted above, is unrelated to the vignettes, came later in the survey, and is not analyzed in the present study. The thresholds are again based on natural breaking points in the data, as well as on our assessment regarding reasonable minimum and maximum completion times. We were thus left with a final sample of 660 participants, of which 323 (49%) were randomly allocated to the control condition and 337 (51%) to the PL condition. The characteristics of the sample are presented in Table 1. As in the first stage, no significant differences were found between the conditions in any of the socio-demographic or other personal characteristics examined (although “income” approaches conventional significance levels; see Appendix 3 - Table 8).

Procedure and instrument

This stage of the experiment took place between January 30 and February 7, 2024. The questionnaire was identical to the one used in the first stage, except for its third section, which, as noted above, was not included. Importantly, this section of the questionnaire is unrelated to the vignette and came after it in the questionnaire. The newspaper article in the control condition was identical to the one used in the first stage of the experiment. The newspaper article in the PL condition emphasized proportionality between the crime and the response provided by the police, and the fact that the officers applied only the minimum level of coercion necessary to address the situation (see Appendix 2). This was expressed in what the officer told the reporter about the event (“It was important for me to handle the event, but without getting into a situation of too much violence. After all, these are not murderers…”) and in the witnesses’ accounts (“But to their credit, they did not exaggerate the force they used and brought just one police car so there was not too much of a fuss.”; “The officers’ responses were absolutely proportionate – they handled the suspects without making too much of a fuss or bringing in a large number of units. My impression is that this was a targeted operation, as should be with such crimes.”).

Measures

Two survey items were designed to capture proportionality between the crime and the response (items 14 and 15 in Table 3), and they were thus combined to form a “proportionality index” (M = 4.27, SD = 0.84, range 1.00–5.00, Spearman’s rho = 0.60, p < 0.001). A single item (item 16 in Table 3) was used as an indicator for the police applying only the minimum level of coercive authority necessary. The main DVs are identical to those used in the first stage of the experiment (see Table 4) (“Legitimacy index” M = 4.16, SD = 0.73, range 1.00–5.00, Cronbach’s alpha = 0.76; “Satisfaction index” M = 4.20, SD = 0.80, range 1.00–5.00, Cronbach’s alpha = 0.83; “Willingness to obey index” M = 4.54, SD = 0.66, range 1.00–5.00, Spearman’s rho = 0.43, p < 0.001).

Stage II: analyses and results

Manipulation checks

In order to examine if the PL condition was perceived by participants as intended, we compared the means of the “proportionality index” across the two conditions. An independent-samples t-test revealed that evaluations regarding the police being proportionate in their response were significantly higher in the PL condition (N = 321, M = 4.46, SD = 0.79) than in the control condition (N = 264, M = 4.04, SD = 0.84) (t(583) = − 6.11; p < 0.001; Cohen’s d = − 0.508). A Chi-square test for independence also revealed a statistically significant difference between the groups in their response to survey item 16 in Table 3 (“The officers in the article exercised the minimum level of enforcement necessary, no more”) (N = 613, \({\chi }^{2}\) = 39.53; p < 0.001; DF = 4). For example, in the PL condition, 40.18% of the respondents indicated that they “completely agree” with this statement, while in the control condition only 20.90% provided this answer. This indicates that police responses to the event were perceived as intended in the PL condition—more proportionate and minimal in their level of intrusion.

T-tests of the main effects

In order to examine if the PL condition increased police legitimacy, satisfaction, and willingness to obey the officers, three independent samples t-tests were conducted. These revealed that legitimacy scores were significantly higher in the PL condition (N = 269, M = 4.30, SD = 0.68) than in the control condition (N = 251, M = 4.00, SD = 0.74) (t(518) = − 4.79; p < 0.001; Cohen’s d = − 0.42). Similarly, satisfaction scores were significantly higher in the PL condition (N = 303 M = 4.37, SD = 0.72) than in the control condition (N = 271, M = 4.02, SD = 0.84) (t(533.06) = − 5.28; p < 0.001; Cohen’s d = − 0.44), and scores on the “willingness to obey” index were significantly higher in the PL condition (N = 304, M = 4.62, SD = 0.59) than in the control condition (N = 305, M = 4.47, SD = 0.71) (t(588.96) = − 2.82; p < 0.01; Cohen’s d = − 0.23). These findings suggest that the effects of the SC manipulation in the first stage of the experiment on all three main DVs are not likely to only be the outcome of its PJ and effectiveness components. The two unique features of the SC model, which were the focus of the second stage of the experiment, showed independent, statistically significant effects.

Discussion

In line with the findings of Jonathan-Zamir et al. (2023), in the first stage of our experiment, evaluations of the extent to which the police complied with the restrictions on their authority dictated by the SC appeared to be no less important than the two “classic” antecedents of legitimacy, which have been the focus of much of the research in this area. With regard to evaluations of the officers’ legitimacy, the SC model was as effective as the PJ and PP models. In terms of our second main DV—satisfaction with the way the officers handled the situation—the SC manipulation was no different in its impact than the PP manipulation, and both showed a larger effect than that of the PJ manipulation. Finally, in terms of willingness to obey the officers, the effect of police compliance with the SC was similar to that of police-provided PJ, while the PP manipulation had no significant effect on willingness to obey.

On their own, these finding may raise questions about the source of the effects of the SC model: given its partial overlap with the PJ and effectiveness models, one may suspect that its effects simply reflect the effects of its PJ and effectiveness components. At the same time, the second stage of the experiment reveals that this is unlikely to be the case, given the independent effects of the two unique components of the SC model (proportionality between the crime and the response, and applying the minimum level of coercive authority necessary to handle the situation) on all three DVs. Thus, the SC model appears to bring something new to the table, above and beyond the effects of its PJ and effectiveness components. Interestingly, as reviewed by Jonathan-Zamir et al. (2023), proportionality between the crime and the response, and using the least restrictive alternative to deal with the situation, were recently raised by Sherman (2023) in the context of what he argues are current threats to police legitimacy. These include, in his view, policing that is “disproportionate in the harm it causes relative to the harm it prevents” (p. 20), and disconnect between the people, situations and places where most of the crime concentrates, and the level of police intrusion.

These ideas, together with the findings of the present study, suggest that public views of the extent to which the police comply with the SC have merit as an antecedent of police legitimacy. Thus, we encourage researchers to consider these views when investigating public attitudes toward the police, and particularly when seeking to illuminate the sources of police legitimacy, as well as of other socially desirable outcomes (e.g., willingness to obey police directives and satisfaction with the police). We also encourage police practitioners and policy makers striving to strengthen police legitimacy to work toward improving not only procedurally just and effective policing, but also policing that seeks proportionality between the crime and the response, and applies only the minimum level of coercive authority necessary.

Despite these insights, we think that the story is far from complete. Specifically, the overlap between the “building blocks” of police compliance with the SC and those of the two “classic” antecedents of legitimacy (PJ and PP), as well as the identification of the two “new” police-related considerations embedded in SCT (proportionality and least restrictive alternative), draw attention to an important question which, to date, received only little attention—what are the relative effects of each individual component of PJ, PP, police compliance with the SC, and perhaps other police-related considerations not covered by these models, on police legitimacy and its expected outcomes?

With regard to PJ, there is some evidence to suggest that the relative importance of the four components varies across situations (Barrett-Howard & Tyler, 1986). There is also some indication that the components capturing the quality of the interpersonal treatment (dignity and trustworthy motives) influence overall views of “fair treatment” more than the components representing the quality of the decision-making processes (participation and neutrality; see Solomon, 2019; Tyler, 2009; Tyler & Fagan, 2008; Tyler & Huo, 2002). Clearly, there is room for further investigation of this question in terms of PJ (see Nivette et al., 2022), but we suggest taking this line of research a step further, and examining the relative effects of all types of considerations noted above. The first stage of our study treated PJ, police compliance with the SC and PP as “blends,” in which each “ingredient” works together with the other ingredients in the “mix” (and indeed, may well work differently in a different mix). The second stage of the experiment focused on the unique effects of proportionality and least restrictive alternative, but as a pair, and without comparing their effects to those of the other “ingredients.” While the present study was not designed in a way that allows us to isolate and compare the unique effect of each of the nine components making up our three manipulations (see Table 2), we view this question as an important avenue for future research.

Relatedly, it should be noted that there may be other types of concrete evaluations about the police that may impact police legitimacy and other outcomes, which, to date, have not been recognized. In this sense, we encourage researchers to “keep an open mind” about the antecedents of police legitimacy, and strive to further develop the model based on insights from theories or bodies of work which, perhaps, have not been considered in this context. We found the insights gained from SCT and the empirical findings that followed (i.e., Jonathan-Zamir et al., 2023, as well as the findings of the present study), to be a good example of this approach. Nevertheless, we should also note in this context that all types of “extra efforts” displayed by the police in our study, whether it be PJ, PP, SC, or PL, significantly improved scores on the DVs in all but one comparison (the PP condition did not improve willingness to obey the officers). While some “extra efforts” led to improvements that were statistically significant better than others, the differences were not large. Overall, it appears that there is a broad array of “extra efforts” the police can engage in in order to strengthen socially desirable outcomes, and at times it does not appear to matter what approach is taken. Any type of “extra effort” is better than none.

Before concluding, the limitations of the present study should be noted. First, like all vignette experiments, the present study created an artificial situation and relied on participants’ reporting of perceptions and behavioral intentions. Clearly, participants may have felt or responded differently had they actually experienced the situation (e.g., Atzmüller & Stener, 2010). At the same time, it is important to emphasize that in the present study participants were asked to judge a realistic police-citizen interaction (which was based on a true event) about which they learned through a newspaper article. This setting of reading a news item about how the police responded to an event is arguably less artificial and close to how citizens often develop their views about the police. Nevertheless, the effects of police compliance with the SC clearly warrant additional research, particularly using designs that bear the potential for stronger external validity, such as randomized field trials (e.g., Weisburd et al., 2022b).

Second, our sample is based on Israeli panelists. While it provides a broad representation of different populations (for example, in terms of age, income and education) compared to the popular university students-based samples (see review by Nivette et al., 2022), the generalization of our findings clearly requires replications in other countries, populations, and samples. Third, in our experiment, participants were asked to consider police responses to a relatively “light” and “neutral” scenario. It may be that procedurally just policing, performance-oriented policing, and policing that complies with the SC have different effects in other settings, for example, in interactions involving serious violence or in politically sensitive contexts. Thus, we encourage the replication of our experiment using various contexts of police-citizen interactions. Finally, the present study treated attitudes and behavioral intentions as the DVs: the legitimacy of the officers, satisfaction with the way they handled the encounter, and willingness to obey them. Future research is encouraged to consider attitudinal outcomes as mediators rather than the outcome variables, and use true behavioral outcome measures, such as actual compliance with the law, as the main DVs.

Conclusions

Evaluations of the extent to which the police meet the terms of the SC are clearly important to citizens when developing their views of police legitimacy, their satisfaction with the police, and their willingness to obey the officers’ directives. These findings draw particular attention to the two elements of the SC model not already covered by the concepts of PJ or PP—proportionality between the crime and police response, and applying only the minimum level of coercive authority necessary to deal with the problem. Thus, police researchers and practitioner are encouraged to acknowledge not only procedural fairness and effectiveness in their work, but also proportionality and minimal coercion. Researchers are also encouraged to adopt a broad view when considering potential antecedents of police legitimacy and other desirable outcomes, and take note of theories/bodies of work which, to date, have not been considered in this context. We also suggest thinking beyond the effects of models that are “fusions” of more specific evaluations (e.g., PJ), and testing the effects of the individual “ingredients” making up these “fusions.” This would ideally allow us to identify the optimal “mix” of behaviors officers should engage in in order to cultivate and sustain police legitimacy.

Notes

On December 25, 2023, a Google Scholar search with the terms “police legitimacy,” “procedural justice” and “Tyler” yielded 6110 results.

It should be noted that the perceived fairness of the outcome (as opposed to the fairness of the process), or “distributive justice,” has also been acknowledged as a potential antecedent of police legitimacy (Tyler, 1990). Nevertheless, it has received significantly less attention than the two main predictors of legitimacy (McLean, 2020).

References

Atzmüller, C., & Steiner, P. M. (2010). Experimental vignette studies in survey research. Methodology, 6(3), 128–138. https://doi.org/10.1027/1614-2241/a000014

Barrett-Howard, E., & Tyler, T. R. (1986). Procedural justice as a criterion in allocation decisions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 50(2), 296–304. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.50.2.296

Blader, S. L., & Tyler, T. R. (2003). A four-component model of procedural justice: Defining the meaning of a “fair” process. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 29(6), 747–758. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167203029006007

Bolger, P. C., & Walters, G. D. (2019). The relationship between police procedural justice, police legitimacy, and people’s willingness to cooperate with law enforcement: A meta-analysis. Journal of Criminal Justice, 60, 93–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2019.01.001

Bottoms, A., & Tankebe, J. (2012). Beyond procedural justice: A dialogic approach to legitimacy in criminal justice. The Journal of Criminal Law & Criminology, 102, 119–170.

Bradford, B., Murphy, K., & Jackson, J. (2014). Officers as mirrors: Policing, procedural justice and the (re)production of social identity. British Journal of Criminology, 54(4), 527–550.

Cohen, H. S., & Feldberg, M. (1991). Power and restraint: The moral dimension of police work. Praeger Publishers.

Curran, P. G. (2016). Methods for the detection of carelessly invalid responses in survey data. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 66, 4–19.

Dai, M., Frank, J., & Sun, I. (2011). Procedural justice during police-citizen encounters: The effects of process-based policing on citizen compliance and demeanor. Journal of Criminal Justice, 39(2), 159–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2011.01.004

Desmond, M., Papachristos, A. V., & Kirk, D. S. (2016). Police violence and citizen crime reporting in the black community. American Sociological Review, 81(5), 857–876. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122416663494

Dickson, E. S., Gordon, S. C., & Huber, G. A. (2022). Identifying legitimacy: Experimental evidence on compliance with authority. Science Advances, 8(7), eabj7377. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abj7377

Factor, R., Castilo, J. C., & Rattner, A. (2014). Procedural justice, minorities, and religiosity. Police Practice and Research, 15(2), 130–142.

Gau, J. M., Corsaro, N., Stewart, E. A., & Brunson, R. K. (2012). Examining macro-level impacts on procedural justice and police legitimacy. Journal of Criminal Justice, 40(4), 333–343.

Gubler, J. R., Halperin, E., & Hirschberger, G. (2015). Humanizing the outgroup in contexts of protracted intergroup conflict. Journal of Experimental Political Science, 2(1), 36–46.

Hinds, L., & Murphy, K. (2007). Public satisfaction with police: Using procedural justice to improve police legitimacy. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Criminology, 40(1), 27–42.

Huq, A. H., Jackson, J., & Trinkner, R. (2017). Legitimating practices: Revisiting the predicates of police legitimacy. British Journal of Criminology, 57, 1101–1122.

Jackson, J., Bradford, B., Hough, M., Myhill, A., Quinton, P., & Tyler, T. R. (2012). Why do people comply with the law? Legitimacy and the influence of legal institutions. British Journal of Criminology, 52, 1051–1071. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azs032

Jackson, J., Bradford, B., Stanko, B., & Hohl, K. (2013). Just authority? Trust in the police in England and Wales. Routledge.

Jackson, J., Tyler, T. R., Hough, M., Bradford, B., & Mentovich, A. (2015). Compliance and legal authority. In J. D. Wright (Ed.), International encyclopedia of the social & behavioral sciences (pp. 456–462). Elsevier.

Jonathan-Zamir, T., Mastrofski, S. D., & Moyal, S. (2015). Measuring procedural justice in police-citizen encounters. Justice Quarterly, 32(5), 845–871.

Jonathan-Zamir, T., Perry, G., & Willis, J. J. (2023). Ethical perspectives and police science: Using Social Contract Theory as an analytical framework for evaluating police legitimacy. Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice, 17. https://doi.org/10.1093/police/paad056

Jonathan-Zamir, T., & Weisburd, D. (2013). The effects of security threats on antecedents of police legitimacy: Findings from a quasi-experiment in Israel. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 50(1), 3–32.

Kleinig, J. (2014). Legitimate and illegitimate uses of police force. Criminal Justice Ethics, 33(2), 83–103.

Kochel, T. R. (2012). Can police legitimacy promote collective efficacy? Justice Quarterly, 29(3), 384–419. https://doi.org/10.1080/07418825.2011.561805

Kochel, T. R. (2018). Police legitimacy and resident cooperation in crime hotspots: Effects of victimisation risk and collective efficacy. Policing and Society, 28(3), 251–270.

Lawson, B. (1990). Crime, minorities, and the social contract. Criminal Justice Ethics, 9(2), 16–24.

Leventhal, G. S. (1980). What should be done with equity theory? New approaches to the study of fairness in social relationships. In K. J. Gergen, M. S. Greenberg, & R. H. Willis (Eds.), Social exchange (pp. 27–55). Plenum Press.

Lind, E. A., & Tyler, T. R. (1988). The social psychology of procedural justice. Plenum Press.

Locke, J. (1690). Second treatise of government. Hackett Publishing Company.

Mazerolle, L., Antrobus, E., Bennett, S., & Tyler, T. R. (2013a). Shaping citizen perceptions of police legitimacy: A randomized field trial of procedural justice. Criminology, 51(1), 33–63. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.2012.00289.x

Mazerolle, L., Bennett, S., Antrobus, E., & Eggins, E. (2012). Procedural justice, routine encounters and citizen perceptions of police: Main findings from the Queensland Community Engagement Trial (QCET). Journal of Experimental Criminology, 8(4), 343–367. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-012-9160-1

Mazerolle, L., Bennett, S., Davis, J., Sargeant, E., & Manning, M. (2013b). Procedural justice and police legitimacy: A systematic review of the research evidence. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 9(3), 245–274.

McLean, K. (2020). Revisiting the role of distributive justice in Tyler’s legitimacy theory. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 16, 335–346.

Murphy, K., & Cherney, A. (2011). Fostering cooperation with police: How do ethnic minorities in Australia respond to procedural justice-based policing? Australian and New Zealand Journal of Criminology, 44(2), 235–257.

Murphy, K., Williamson, H., Sargeant, E., & McCarthy, M. (2020). Why people comply with COVID-19 social distancing restrictions: Self-interest or duty? Australian & New Zealand Journal of Criminology, 53(4), 477–496. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004865820954484

Nagin, D. S., & Telep, C. W. (2017). Procedural justice and legal compliance. Annual Review of Law and Social Science, 13, 5–28.

Nagin, D. S., & Telep, C. W. (2020). Procedural justice and legal compliance: A revisionist perspective. Criminology & Public Policy, 19(3), 761–786.

Nisbett, R. E., & Wilson, T. D. (1977). The halo effect: Evidence for unconscious alteration of judgments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 35(4), 250.

Nivette, A., Nägel, C., & Stan, A. (2022). The use of experimental vignettes in studying police procedural justice: A systematic review. Journal of Experimental Criminology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-022-09529-7

Perry, G., & Jonathan-Zamir, T. (2020). Expectations, effectiveness, trust, and cooperation: public attitudes towards the Israel Police during the COVID-19 pandemic. Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice, 14(4), 1073–1091.

Perry, G., Jonathan-Zamir, T., & Factor, R. (2022). The long-term effects of policing the COVID-19 pandemic: Public attitudes toward the police in the ‘new normal.’ Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice, 16(1), 167–187.

Reisig, M. D., & Lloyd, C. (2009). Procedural justice, police legitimacy, and helping the police fight crime: Results from a survey of Jamaican adolescents. Police Quarterly, 12, 42–62.

Reisig, M. D., & Parks, R. B. (2000). Experience, quality of life, and neighborhood context: A hierarchical analysis of satisfaction with police. Justice Quarterly, 17, 607–630.

Schori-Eyal, N., Tagar, M. R., Saguy, T., & Halperin, E. (2015). The benefits of group-based pride: Pride can motivate guilt in intergroup conflicts among high glorifiers. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 61, 79–83.

Schulhofer, S. J., Tyler, T. R., & Huq, A. Z. (2011). American policing at a crossroads: Unsustainable policies and the procedural justice alternative. Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology, 101(2), 335–374.

Sherman, L. (2023). Three tiers for evidence-based policing: Targeting “minimalist” policing with a risk-adjusted disparity index. In D. Weisburd, T. Jonathan-Zamir, G. Perry, & B. Hasisi (Eds.), The future of evidence-based policing (pp. 19–43). Cambridge University Press.

Solomon, S. J. (2019). How do the components of procedural justice and driver race influence encounter specific perceptions of police legitimacy during traffic stops? Criminal Justice and Behavior, 46(8), 1200–1216. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854819.859606

Sunshine, J., & Tyler, T. R. (2003). The role of procedural justice and legitimacy in shaping public support for policing. Law & Society Review, 37(3), 513–548.

Thibaut, J., & Walker, L. (1975). Procedural justice: A psychological analysis. Erlbaum.

Thorndike, E. L. (1920). A constant error in psychological ratings. Journal of Applied Psychology, 4(1), 25–29.

Trinkner, R., Jackson, J., & Tyler, T. R. (2018). Bounded authority: Expanding “appropriate” police behavior beyond procedural justice. Law and Human Behavior, 42(3), 280.

Tyler, T. R. (1990). Why people obey the law. Yale University Press.

Tyler, T. R. (2004). Enhancing police legitimacy. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 593(1), 84–99.

Tyler, T. R. (2006). Psychological perspectives on legitimacy and legitimation. Annual Review of Psychology, 57(1), 375–400. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190038

Tyler, T. R. (2009). Legitimacy and criminal Justice: The benefits of self-regulation. Ohio State Journal of Criminal Law, 7, 307–359.

Tyler, T. R., & Blader, S. L. (2000). Cooperation in groups: Procedural justice, social identity, and behavioral engagement. Psychology Press.

Tyler, T. R., Boeckmann, R., Smith, H. J., & Huo, Y. J. (1997). Social justice in a diverse society. Westview Press.

Tyler, T. R., & Fagan, J. (2008). Legitimacy and cooperation: Why do people help the police fight crime in their communities. Ohio State Journal of Criminal Law, 6, 231–275.

Tyler, T. R., Fagan, J., & Geller, A. (2014). Street stops and police legitimacy: Teachable moments in young urban men’s legal socialization. Journal of Empirical Legal Studies, 11(4), 751–785. https://doi.org/10.1111/jels.12055

Tyler, T. R., Goff, P. A., & MacCoun, R. J. (2015). The impact of psychological science on policing in the United States: Procedural justice, legitimacy, and effective law enforcement. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 16(3), 75–109.

Tyler, T. R., & Huo, Y. (2002). Trust in the law: Encouraging public cooperation with the police and courts. Russell Sage Foundation.

Tyler, T. R., & Jackson, J. (2014). Popular legitimacy and the exercise of legal authority: Motivating compliance, cooperation, and engagement. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 20(1), 78–95. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034514

Tyler, T. R., & Lind, E. A. (1992). A relational model of authority in groups. In Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 25, pp. 115–191). Academic Press.

Tyler, T., & Nobo, C. (2023). Legitimacy-based policing and the promotion of community vitality. Cambridge University Press.

Walters, G. D., & Bolger, P. C. (2019). Procedural justice perceptions, legitimacy beliefs, and compliance with the law: A meta-analysis. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 15(3), 341–372. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-018-9338-2

Weisburd, D., Jonathan-Zamir, T., White, C., Wilson, D. B., & Kuen, K. (2022a). Are the police primarily responsible for influencing place-level perceptions of procedural justice and effectiveness? A longitudinal study of street segments. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. https://doi.org/10.1177/00224278221120225

Weisburd, D., & Majmundar, M. (Eds). (2018). Proactive policing: Effects on crime and communities. The National Academies Press. Available from: https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/24928/proactive-policing-effects-on-crime-and-communities

Weisburd, D., Telep, C. W., Vovak, H., Zastrow, T., Braga, A. A., & Turchan, B. (2022b). Reforming the police through procedural justice training: A multicity randomized trial at crime hot spots. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 119(14), e2118780119.

Weitzer, R., & Tuch, S. A. (2002). Perceptions of racial profiling: Race, class, and personal experience. Criminology, 40(2), 435–456.

White, M. D., Mulvey, P., & Dario, L. M. (2016). Arrestees’ perceptions of the police: Exploring procedural justice, legitimacy, and willingness to cooperate with police across offender types. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 43(3), 343–364.

Wolfe, S. E., Nix, J., Kaminski, R., & Rojek, J. (2016). Is the effect of procedural justice on police legitimacy invariant? Testing the generality of procedural justice and competing antecedents of legitimacy. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 32(2), 253–282. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-015-9263-8

Wolff, J. (2023). An introduction to political philosophy. Oxford University Press.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Hebrew University of Jerusalem. This research was supported by the Aharon Barak Center for Interdisciplinary Legal Research, Faculty of Law, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Appendix 2. Vignettes of study conditions

Note: All vignettes have been translated from Hebrew and edited. Manipulation-specific sections are italicized.

I. Control condition:

Beware! A man crawling on the beach did this

Recently, the beaches have been filled with swimmers and sunseekers, but some more questionable characters have also joined the crowd. Last night, the police stepped in.

Have you heard of “beach thieves”? It is a phenomenon of which the police are well aware, and the number of incidents increases in the summer season when many, who come to the beaches to swim and hang out, go in the water and leave their belongings on the sand. On Sunday and Monday this week the police took action.

Local police officers took steps to thwart the theft of cellphones and handbags belonging to a group of young people lounging on the beach. The police located two suspects who allegedly tried to steal from the youngsters who were sitting on the sand.

How did the system work?

One of the suspects was observed crawling over the sand in an attempt to get closer to the youngsters’ bags, while his accomplice was on the lookout in order to provide a warning if the police came near. The suspects never imagined that two plainclothes police officers were on the spot. Suddenly, the officers noticed a man crawling over the beach between lifeguard stations 3 and 4.

“We moved in their direction,” said one of the officers (the full name is withheld by the editorial board). “Under the blue shed between the two lifeguard stations, I noticed another suspect on the lookout making sure that no one was coming, and I approached him. The guy who was crawling on the sand got up quickly, and it looked like he dropped something on the sand.”

An eyewitness at the scene said: “I didn’t even notice that there were cops in the area, but suddenly they appeared and there was an incident.”

Another witness added: “It was interesting to see the police in action, but I’m not sure they caught the right people.”

The officers detained the two suspects to check if they were indeed the thieves and if they had a criminal record.

The police department reports that the phenomenon of “beach thieves” is a well-known occurrence at beaches throughout the country.

II. Procedural justice condition (PJ):

Beware! A man crawling on the beach did this

Recently, the beaches have been filled with swimmers and sunseekers, but some more questionable characters have also joined the crowd. Last night, the police stepped in.

Have you heard of “beach thieves”? It is a phenomenon of which the police are well aware, and the number of incidents increases in the summer season when many, who come to the beaches to swim and hang out, go in the water and leave their belongings on the sand. On Sunday and Monday this week the police took action.

Local police officers took steps to thwart the theft of cellphones and handbags belonging to a group of young people lounging on the beach. The police located two suspects who allegedly tried to steal from the youngsters who were sitting on the sand.

How did the system work?

One of the suspects was observed crawling over the sand in an attempt to get closer to the youngsters’ bags, while his accomplice was on the lookout in order to provide a warning if the police came near. The suspects never imagined that two plainclothes police officers were on the spot. Suddenly, the officers noticed a man crawling over the beach between lifeguard stations 3 and 4.

“We moved in that direction,” said one of the officers (the full name is withheld by the editorial board). “It was important for us to catch the thieves, but to do so in a fair and dignified manner, without them or the many citizens around getting too frightened. Afterall, we are at the beach and there are many families and children [around]… Under the blue shed between the two lifeguard stations, I noticed another suspect on the lookout making sure that no one was coming, and I approached him. The guy who was crawling on the sand got up quickly, and it looked like he dropped something on the sand. I approached him, explained that we were there to keep everyone safe, and asked what exactly was he doing.”

An eyewitness at the scene said: “After the officers caught the thieves, I heard that they asked them what had happened and let them tell their side [of the story]. Afterwards, the officers explained to the thieves the severity of what they had done, and informed them that they were now under arrest and would be taken to the station, and also what would happen there. More generally the officers spoke nicely to everyone and acted respectfully.”

Another witness added: “The officers behaved in a pleasant and respectful manner, to the suspects and also to everyone around – they listened to us, let us relate exactly what had happened, and explained the process in detail to them and to us. It was reassuring.”

The officers detained the two suspects to check if they were indeed the thieves and if they had a criminal record.

The police department reports that the phenomenon of “beach thieves” is a well-known occurrence at beaches throughout the country, and officers work over the summer to allow a pleasant and safe swimming season for all.

III. Performance condition (PP):

Beware! A man crawling on the beach did this

Recently, the beaches have been filled with swimmers and sunseekers, but some more questionable characters have also joined the crowd. Last night, the police succeeded in catching two of them in action.

Have you heard of “beach thieves”? It is a phenomenon of which the police are well aware, and the number of incidents increases in the summer season when many, who come to the beaches to swim and hang out, go in the water and leave their belongings on the sand. On Sunday and Monday this week two such thieves were caught red-handed.

In a quick and efficient operation, local police officers succeeded in thwarting the theft of cellphones and handbags belonging to a group of young people lounging on the beach. The police located two suspects who allegedly tried to steal from the youngsters who were sitting on the sand.

How did the system work?

One of the suspects was observed crawling over the sand in an attempt to get closer to the youngsters’ bags, while his accomplice was on the lookout in order to provide a warning if the police came near. The suspects never imagined that two plainclothes police officers were on the spot, ready for quick and effective action. Suddenly, the officers noticed a man crawling over the beach between lifeguard stations 3 and 4.

“We moved in that direction,” said one of the officers (the full name is withheld by the editorial board). “Under the blue shed between the two lifeguard stations, I noticed another suspect on the lookout making sure that no one was coming, and I approached him. The guy who was crawling on the sand got up quickly, and it looked like he dropped something on the sand. Immediately I jumped on him and caught him. A quick response is the name of the game.”

An eyewitness at the scene said: “I didn’t even notice that there were cops in the area, and suddenly they jumped, caught the thieves and took them away. It was very quick and efficient. I really have seen a lot of police around here lately.”

Another witness added: “I have never seen police officers work so quickly! Before I realized what was happening, the officers had already acted efficiently with the suspects and apprehended them. My impression is that this was a quick and effective operation, as should be with such crimes.”

The officers detained the two suspects, and the check they ran at the scene revealed that one of the suspects had a criminal record and was wanted for questioning.

The police department reports that the phenomenon of “beach thieves” is a well-known occurrence at beaches throughout the country, and therefore officers display considerable presence at beaches over the summer.

IV. Compliance with the social contract condition (SC):

Beware! A man crawling on the beach did this

Recently, the beaches have been filled with swimmers and sunseekers, but some more questionable characters have also joined the crowd. Last night, the police succeeded in catching two of them in action.

Have you heard of “beach thieves”? It is a phenomenon of which the police are well aware, and the number of incidents increases in the summer season when many, who come to the beaches to swim and hang out, go in the water and leave their belongings on the sand. On Sunday and Monday this week two such thieves were caught red-handed.

In an efficient operation, local police officers succeeded in thwarting the theft of cellphones and handbags belonging to a group of young people lounging on the beach. The police located two suspects who allegedly tried to steal from the youngsters who were sitting on the sand.

How did the system work?

One of the suspects was observed crawling over the sand in an attempt to get closer to the youngsters’ bags, while his accomplice was on the lookout in order to provide a warning if the police came near. The suspects never imagined that two plainclothes police officers were on the spot, ready for effective action. Suddenly, the officers noticed a man crawling over the beach between lifeguard stations 3 and 4.

“We moved in that direction,” said one of the officers (the full name is withheld by the editorial board). “It was important for us to catch the thieves, but to do so in a fair and dignified manner, without them or the many citizens around getting too frightened. Afterall, we are at the beach and there are many families and children [around]… Under the blue shed between the two lifeguard stations, I noticed another suspect on the lookout making sure that no one was coming, and I approached him. The guy who was crawling on the sand got up quickly, and it looked like he dropped something on the sand. I jumped on him and caught him.”

An eyewitness at the scene said: “I didn’t even notice that there were cops in the area, and suddenly they jumped, caught the thieves and took them away. It was very efficient. They also did not exaggerate the force they used and they brought just one police car so there was not too much of a fuss. More generally the officers spoke nicely to everyone and acted respectfully.”

Another witness added: The officers behaved in a pleasant and respectful manner, and their responses were absolutely proportionate – they acted efficiently with the suspects without making too much of a fuss or bringing in a large number of units. My impression is that this was a targeted and effective operation, as should be with such crimes”.

The officers detained the two suspects, and the check they ran at the scene revealed that one of the suspects had a criminal record and was wanted for questioning.

The police department reports that the phenomenon of “beach thieves” is a well-known occurrence at beaches throughout the country, and officers work over the summer to allow a pleasant and safe swimming season for all.

V. Proportionality + least restrictive alternative condition (PL):

Beware! A man crawling on the beach did this

Recently, the beaches have been filled with swimmers and sunseekers, but some more questionable characters have also joined the crowd. Last night, the police stepped in.

Have you heard of “beach thieves”? It is a phenomenon of which the police are well aware, and the number of incidents increases in the summer season when many, who come to the beaches to swim and hang out, go in the water and leave their belongings on the sand. On Sunday and Monday this week the police took action.

Local police officers took steps to thwart the theft of cellphones and handbags belonging to a group of young people lounging on the beach. The police located two suspects who allegedly tried to steal from the youngsters who were sitting on the sand.

How did the system work?

One of the suspects was observed crawling over the sand in an attempt to get closer to the youngsters’ bags, while his accomplice was on the lookout in order to provide a warning if the police came near. The suspects never imagined that two plainclothes police officers were on the spot. Suddenly, the officers noticed a man crawling over the beach between lifeguard stations 3 and 4.

“We moved in their direction,” said one of the officers (the full name is withheld by the editorial board). “It was important for me to handle the event, but without getting into a situation of too much violence. After all, these are not murderers…Under the blue shed between the two lifeguard stations, I noticed another suspect on the lookout making sure that no one was coming, and I approached him. The guy who was crawling on the sand got up quickly, and it looked like he dropped something on the sand.”