Abstract

Objectives

This study tested whether a police-led initiative providing a CPTED (Crime Prevention by Environmental Design) intervention to residential burglary victims reduced revictimisation.

Methods

Victims of eligible burglaries were randomly allocated to intention-to-treat and control groups in three New Zealand Police districts. Following the qualifying burglary, intention-to-treat victims were offered free installation of window and door locks, security lights and improved lines of sight (foliage trimming). Revictimisation, perceptions of safety and police, and displacement outcomes were measured using police administrative data and a survey of victims.

Results

During the first trial year, there was no effect on revictimisation but positive effects on victims’ perceptions. Supplementary analyses suggest implementation and contextual factors which contributed to the lack of effect on revictimisation.

Conclusions

The findings highlight the limitations of CPTED interventions in particular contexts and confirm the importance of delivering prompt, contextually tailored interventions for the prevention of repeat burglary victimisation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

This paper reports the RCT aspect of the evaluation of the initiative, not all evaluation questions, which included process measures exploring barriers to and enablers of the successful implementation of the trial.

These figures include a small number of properties that received the intervention in error and those that received the intervention following a repeat.

For burglaries reported to have occurred at an unknown time within a date range, the end of that date range was used to determine whether an offence was within the trial period, and the timing of repeat victimisations.

We thank an anonymous reviewer for the suggestion to include the survival analyses, which were not in the original Evaluation Plan.

The survey was not sent to ITT group victims who did not participate in the trial, as the information sheet provided to victims stated that no details would be passed on to the evaluators (for the survey) if they declined to participate. We checked whether decliners did so due to negative perceptions of police, which would have biased the intervention group survey sample towards those with pre-existing positive views. Only a small minority (<8%) expressed anti-police views in declining to participate (reasons for declining were solicited by staff when offering the intervention and recorded by the District Coordinators). The most common reasons were considering their existing or planned security measures sufficient and pending changes in tenancy or ownership.

In determining the desired sample size for the survey, we were guided by Johnson et al. (2018), who conducted a similar survey. We likewise aimed for a minimum sample size of 400 respondents in order to detect a 10% difference between groups at 80% power.

These measures were not in the original Evaluation Plan but were added during survey design due to increased attention to and prioritisation of these issues by NZ Police.

We investigated the uneven split (55%:45%) between the control and ITT groups and found no evidence that file reference numbers could have been or were manipulated to generate more even-ending (control group) file numbers than odd-ending (ITT group) file numbers and thus believe it to be a statistical anomaly.

Further comparisons added during the review process revealed no statistically significant differences in ‘eligible’ or ‘any’ revictimisation between the intervention group and either the ‘declined’ group (21 of 171 revictimised, 12 of which were eligible repeats) or the ‘no security measures needed’ group (6 of 55 revictimised, 4 of which were eligible repeats). For monitoring purposes during the trial the District Coordinators recorded, where given, potential participants’ reasons for declining; the most common reason they gave was that they perceived there was no need for any of the LLL measures on offer. The lack of difference between these groups is therefore unsurprising.

Another possible interpretation of this finding is that the control group’s responses were a product of social desirability bias (Phillips, 1980), influencing them to provide a more socially desirable response, feeling pressure to say they had acted on advice from police. However, we don’t believe this to be the case. Participants were informed their responses were confidential to the independent company conducting the survey and would have no bearing on any future dealings they may have with the police. Moreover, the survey also asked what measures respondents planned but had not yet taken; respondents feeling pressure to respond in a socially desirable way would have been more likely to respond to this question positively than the question about what security measures they had actually taken (for this reason we cannot reliably compare the control and intervention groups' responses about what measures were planned).

Where there was a date range within which the offence could have occurred, the ‘end date’ was used to determine eligibility, and in all analyses, as reflective of the latest date at which the offence occurred.

In rural areas not covered by SOCOs, the assessments were conducted by the local officers who responded to the burglary.

As some properties were Housing New Zealand (HNZ) properties, the list was restricted to items approved by HNZ, to ensure equitable availability across all eligible properties.

These criteria were not set at the start of the trial but were identified as these circumstances arose, at which point codes were created to track these reasons for attrition.

An automatic consent from Housing New Zealand covering all its properties was agreed prior to the start of the trial.

Control vs intervention for any measures: 63.8% vs 57.2%, X2 (df = 1, N = 655) = 2.7, p = .10, Cramér’s V = 0.1, 95% CI -14.3% - +1.2%. Door locks: 29.1% vs 22.0%, X2 (df = 1, N = 655) = 3.9, p <.05, Cramér’s V = 0.1, 95% CI -14.0% - -1.1%. Window stays: 24.9% vs 10.7%, X2 (df = 1, N = 655) = 21.5, p <.001, Cramér’s V = 0.2, 95% CI -20.3% - -8.2%. Lights: 39.8% vs 17.3%, X2 (df = 1, N = 655) = 39.1, p <.001, Cramér’s V = 0.2, 95% CI -29.4% - -15.5%.

While officers responded to burglaries and carried out assessments 24/7, the Coordinators operated Monday to Friday, with burglaries reported over the weekend being logged and followed up on Mondays.

Changes in the police’s crime statistics reporting system prior to the 3 year pre-intervention period precluded the use of a longer time series to enable more robust estimation of seasonal patterns.

References

Armitage, R. (2000). An evaluation of Secured by Design Housing within West Yorkshire – Briefing Note 7/00 (Briefing Note 7/00). Home Office. https://popcenter.asu.edu/sites/default/files/04-Armitage.pdf. Accessed date 13 Jul 2021.

Armitage, R. (2013). Crime prevention through housing design: Policy and practice. Palgrave Macmillan.

Armitage, R. (2018). Domestic burglary: Burglar responses to target attractiveness. In A. Tseloni, R. Thompson, & N. Tilley (Eds.), Reducing burglary (pp. 45–75). Cham.

Armitage, R. (2018). Burglars’ take on crime prevention through environmental design (CPTED): Reconsidering the relevance from an offender perspective. Security Journal, 31(1), 285–304. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41284-017-0101-6

Armitage, R., & Monchuk, L. (2011). Sustaining the crime reduction impact of designing out crime: Re-evaluating the Secured by Design scheme 10 years on. Security Journal, 24(4), 320–343. https://doi.org/10.1057/sj.2010.6

Ashcroft, E., Verheyen, N., & Smith, M. (2021, October). Locks, lights and lines of sight: A randomised control trial testing the effectiveness of simple prevention measures to tackle repeat burglary [Presentation]. Australia and New Zealand Society of Evidence Based Policing Conference, online. https://www.anzsebpconference.com.au/. Accessed date 14 Sep 2021.

Bowers, K., & Johnson, S. (2006). Implementation failure and success: Some lessons from England. In Putting theory to work: Implementing situational prevention and problem-oriented policing. (pp. 163–198). Criminal Justice Press.

Brodersen, K. H., Gallusser, F., Koehler, J., Remy, N., & Scott, S. L. (2015). Inferring causal impact using Bayesian structural time-series models. The Annals of Applied Statistics, 9(1), 247–274. https://doi.org/10.1214/14-AOAS788

Budz, D., Pegnall, N., & Townsley, M. (2001). Lightning strikes twice: Preventing repeat home burglary. Criminal Justice Commission.

Chainey, S. P., Curtis-Ham, S. J., Evans, R. M., & Burns, G. J. (2018). Examining the extent to which repeat and near repeat patterns can prevent crime. Policing: An International Journal, 41(5), 608–622. https://doi.org/10.1108/PIJPSM-12-2016-0172

Chainey, S. P., & da Silva, B. F. A. (2016). Examining the extent of repeat and near repeat victimisation of domestic burglaries in Belo Horizonte, Brazil. Crime Science, 5(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40163-016-0049-6

Clare, J. (2011). Examination of systematic variations in burglars’ domain-specific perceptual and procedural skills. Psychology, Crime & Law, 17(3), 199–214. https://doi.org/10.1080/10683160903025810

Clarke, R. V. (1980). “Situational” crime prevention: Theory and practice. The British Journal of Criminology, 20(2), 136–147. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.bjc.a047153

Clarke, R. V. (Ed.). (1997). Situational crime prevention: Successful case studies (2nd ed.). Harrow and Heston.

Cromwell, P. F., Olson, J. N., & Avary, D. W. (1990). Breaking and entering: An ethnographic analysis of burglary (1st ed.). Sage.

Curtis-Ham, S., & Walton, D. (2018). The New Zealand crime harm index: Quantifying harm using sentencing data. Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice, 12(4), 455–467. https://doi.org/10.1093/police/pax050

Elffers, H., & Morgan, F. (2019). To what extent is revictimization risk mitigated by police prevention advice after a previous burglary? Crime Prevention and Community Safety, 21(1), 61–67. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41300-018-0055-6

Ellingworth, D., Hope, T., Osborn, D. R., Trickett, A., & Pease, K. (1997). Prior victimisation and crime risk. International Journal of Risk, Security and Crime Prevention, 2(3), 201–214.

Farrell, G. (1995). Preventing repeat victimization. Crime and Justice, 19, 469–534. https://doi.org/10.1086/449236

Farrell, G., & Pease, K. (2017). Preventing repeat and near repeat crime concentrations. In N. Tilley & A. Sidebottom (Eds.), Handbook of crime prevention and community safety (2nd ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315724393

Farrell, G., Phillips, C., & Pease, K. (1995). Like taking candy: Why does repeat victimization occur? The British Journal of Criminology, 35(3), 384–399. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.bjc.a048523

Farrell, G., Sousa, W., & Lamm Weisel, D. (2002). The time-window effect in the measurement of repeat victimization: A methodology for its measurement and an empirical study. In N. Tilley (Ed.), Analysis for crime prevention (Vol. 13, pp. 15–27). Criminal Justice Press.

Fixsen, D. L., Naom, S. F., Blase, K. A., Friedman, R. M., & Wallace, F. (2005). Implementation research: A synthesis of the literature (No. 231; FMHI Publication). National Implementation Research Network, Louis de la Parte Florida Mental Health Institute, University of South Florida. http://ctnlibrary.org/pdf/nirnmonograph.pdf. Accessed date 19 Feb 2020.

Groff, E., & Taniguchi, T. (2019). Using citizen notification to interrupt near-repeat residential burglary patterns: The micro-level near-repeat experiment. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 15(2), 115–149. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-018-09350-1

Groff, E., & Taniguchi, T. (2019). Quantifying crime prevention potential of near-repeat burglary. Police Quarterly, 22(3), 330–359. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098611119828052

Grove, L., Farrell, G., Farrington, D. P., & Johnson, S. D. (2012). Preventing repeat victimization: A systematic review. Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention.

Guerette, R. T. (2009). Analyzing crime displacement and diffusion. US Department of Justice.

Guerette, R. T., & Bowers, K. (2009). Assessing the extent of crime displacement and diffusion of benefits: A review of situational crime prevention evaluations. Criminology, 47(4), 1331–1368. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.2009.00177.x

Hipp, J. R., Curran, P. J., Bollen, K. A., & Bauer, D. J. (2004). Crimes of opportunity or crimes of emotion? Testing two explanations of seasonal change in crime. Social Forces, 82(4), 1333–1372. https://doi.org/10.1353/sof.2004.0074

Hunter, J., & Tseloni, A. (2018). An evaluation of a research-informed target hardening initiative. In A. Tseloni, R. Thompson, & N. Tilley (Eds.), Reducing burglary (pp. 77–105). Cham.

Johnson, S. D., Bernasco, W., Bowers, K., Elffers, H., Ratcliffe, J., Rengert, G., & Townsley, M. (2007). Space–time patterns of risk: A cross national assessment of residential burglary victimization. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 23(3), 201–219. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-007-9025-3

Johnson, S. D., Davies, T., Murray, A., Ditta, P., Belur, J., & Bowers, K. (2017). Evaluation of Operation Swordfish: A near-repeat target-hardening strategy. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 13(4), 505–525. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-017-9301-7

Johnson, S. D., Guerette, R. T., & Bowers, K. (2014). Crime displacement: What we know, what we don’t know, and what it means for crime reduction. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 10(4), 549–571. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-014-9209-4

Lakens, D. (2021). Sample Size Justification. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/9d3yf. Accessed date 7 Sept 2021.

Larsen, K. (2016). Making causal impact analysis easy. MultiThreaded. https://multithreaded.stitchfix.com/blog/2016/01/13/market-watch/. Accessed date 12 Apr 2019.

Laycock, G., & Tilley, N. (2018). A short history of the England and Wales national burglary security initiatives. In A. Tseloni, R. Thompson, & N. Tilley (Eds.), Reducing burglary (pp. 21–44). Springer.

Linning, S. J., Andresen, M. A., & Brantingham, P. J. (2017). Crime seasonality: Examining the temporal fluctuations of property crime in cities with varying climates. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 61(16), 1866–1891. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624X16632259

Lopez Bernal, J., Cummins, S., & Gasparrini, A. (2018). The use of controls in interrupted time series studies of public health interventions. International Journal of Epidemiology, 47(6), 2082–2093. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyy135

Moffatt, R. E. (1983). Crime prevention through environmental design—A management perspective. Canadian Journal of Criminology, 25(19–31), 19–31.

Moir, E., Hart, T. C., Reynald, D., & Stewart, A. (2019). Typologies of suburban guardians: Understanding the role of responsibility, opportunities, and routine activities in facilitating surveillance. Crime Prevention & Community Safety, 21, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41300-018-0057-4

Nee, C. (2015). Understanding expertise in burglars: From pre-conscious scanning to action and beyond. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 20(Supplement C), 53–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2014.12.006

Nee, C., & Meenaghan, A. (2006). Expert decision making in burglars. The British Journal of Criminology, 46(5), 935–949. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azl013

New Zealand Police. (2019). Annual Report 2018/19. New Zealand Police. https://www.police.govt.nz/sites/default/files/publications/annual-report-2018-2019.pdf. Accessed date 4 Aug 2021.

Newman, O. (1973). Defensible space: People and design in the violent city. Architectural Press.

Neyroud, P. W. (2017). Learning to field test in policing: Using an analysis of completed randomised controlled trials involving the police to develop a grounded theory on the factors contributing to high levels of treatment integrity in police field experiments. [PhD thesis, University of Cambridge]. https://www.repository.cam.ac.uk/handle/1810/268177

Pawson, R., & Tilley, N. (1997). Realistic Evaluation. Sage.

Pease, K. (1998). Repeat victimisation: Taking stock. Home Office.

Pegram, R., Barnes, G. C., Slothower, M., & Strang, H. (2018). Implementing a burglary prevention program with evidence-based tracking: A case study. Cambridge Journal of Evidence-Based Policing, 2(3–4), 181–191. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41887-018-0030-6

Phillips, P. (1980). Characteristics and typology of the journey to crime. In D. E. Georges-Abeyie & K. D. Harries (Eds.), Crime: A spatial perspective (pp. 167–180). Columbia University Press.

Polvi, N., Looman, T., Humphries, C., & Pease, K. (1991). The time course of repeat burglary victimization. The British Journal of Criminology, 31(4), 411–414. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.bjc.a048138

R Core Team. (2013). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. http://www.R-project.org/. Accessed date 1 Oct 2020.

Ratcliffe, J. H., Perenzin, A., & Sorg, E. T. (2017). Operation Thumbs Down: A quasi-experimental evaluation of an FBI gang takedown in South Central Los Angeles. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management, 40(2), 442–458. https://doi.org/10.1108/PIJPSM-01-2016-0004

Reynald, D. (2010). Guardians on guardianship: Factors affecting the willingness to supervise, the ability to detect potential offenders, and the willingness to intervene. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 47(3), 358–390.

Reynald, D., Moir, E., Cook, A., & Vakhitova, Z. (2018). Changing perspectives on guardianship against crime: An examination of the importance of micro-level factors. Crime Prevention & Community Safety, 20, 268–283. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41300-018-0049-4

Robinson, M. B. (1998). Burglary revictimization: The time period of heightened risk. British Journal of Criminology, 38(1), 78–87. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.bjc.a014229

Robinson, M. B. (2000). From research to policy: Preventing residential burglary through a systems approach. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 24(2), 169–179. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02887590

Sanders, A. N., Kuhns, J. B., & Blevins, K. R. (2016). Exploring and understanding differences between deliberate and impulsive male and female burglars. Crime & Delinquency, 63(12), 1547–1571. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011128716660519

Siale, T. (2016). Prevention of repeat burglary: Evidence brief. Ministry of Justice. https://www.justice.govt.nz/assets/Documents/Publications/Repeat-Burglary.pdf. Accessed date 10 Dec 2019.

Stickle, B. F. (2015). Examining public willingness-to-pay for burglary prevention. Crime Prevention and Community Safety, 17(2), 120–138. https://doi.org/10.1057/cpcs.2015.3

Stokes, N., & Clare, J. (2019). Preventing near-repeat residential burglary through cocooning: Post hoc evaluation of a targeted police-led pilot intervention. Security Journal, 32(1), 45–62. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41284-018-0144-3

Thompson, R., Tseloni, A., Tilley, N., Farrell, G., & Pease, K. (2018). Which security devices reduce burglary? In A. Tseloni, R. Thompson, & N. Tilley (Eds.), Reducing burglary (pp. 77–105). Cham.

Tilley, N. (2000). Experimentation and criminal justice policies in the United Kingdom. Crime & Delinquency, 46(2), 194–213. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011128700046002004

Tormene, P., Giorgino, T., Quaglini, S., & Stefanelli, M. (2009). Matching incomplete time series with dynamic time warping: An algorithm and an application to post-stroke rehabilitation. Artificial Intelligence in Medicine, 45(1), 11–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.artmed.2008.11.007

Tseloni, A., Thompson, R., Grove, L., Tilley, N., & Farrell, G. (2017). The effectiveness of burglary security devices. Security Journal, 30(2), 646–664. https://doi.org/10.1057/sj.2014.30

Tseloni, A., Thompson, R., & Tilley, N. (2018). Introduction. In A. Tseloni, R. Thompson, & N. Tilley (Eds.), Reducing burglary (pp. 1–19). Cham, Switzerland. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-99942-5

Acknowledgements

The authors are especially grateful to Dr Melissa Smith and Noeline Verheyen of the New Zealand Police National Prevention Centre, who led the implementation of this initiative, for their input into its evaluation and this paper. We thank Dr Darren Walton and Dr Ross Hendy for their contributions the development of the evaluation, Dr Emma Ashcroft and Simon Williams for comments on earlier drafts of this manuscript, and the anonymous reviewers whose feedback helped refine it. We particularly acknowledge the hard work of the District Coordinators whose commitment ensured ‘no burglary left behind’. We are also grateful to the Ministry of Justice for initiating and supporting the project, and New Zealand Treasury for funding it.

Funding

This project was funded by the New Zealand Treasury as part of Budget 2017’s Social Investment funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

Approval for this study was granted by the New Zealand Ethics Committee (NZEC Application 2018_26). Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study (i.e. those who were offered, and consented to receiving, security measures and those who were invited to participate in the victim survey).

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix A Detailed procedural information about the intervention

Eligibility criteria: technical specifications

The specific technical criteria for eligibility were based on codes used in the NIA system as follows:

-

1.

The offence was coded as a burglary in the National Intelligence Application (NIA).

-

2.

The burglary occurred between 8 June 2018 and 7 June 2019.Footnote 11

-

3.

The case was not recoded to an ineligible offence code or closed with a Closure Reason code of ‘error’, ‘duplicate’, ‘not an offence’. This criterion removed cases which on further investigation were either not burglaries or had been entered in error.

-

4.

The Scene Subtype code was ‘dwelling’ or ‘vacant dwelling’. This criterion filtered to burglaries of residential dwellings, excluding burglaries of outbuildings or yards, other residential premises such as hotels and campervans, and commercial premises.

-

5.

The Method of Entry code was: ‘jemmy/pry’, ‘smash/break’, ‘secure with no sign of forced entry’ or ‘rare’. This criterion excluded burglaries where entry was gained through an unlocked door or open window, or through deception or other interaction with the victim. The categories included involved situations where there were the use of keys/lock picking (making lock improvements relevant) and rare, sophisticated methods of forcing entry such as removing windows entirely (making window stays relevant).

-

6.

The dwelling had its own entrance. This ruled out apartments with communal entry systems, for which the approved list of security measures were not a feasible option.

Process for delivering security measures

Following a burglary, eligible properties randomly assigned to the intention-to-treat group were assessed by Scene of Crime Officers (SOCOs) or responding police officersFootnote 12 to determine which, if any, of the approved security measuresFootnote 13 were lacking. The occupiers (and owners, if different) were then offered participation in the trial unless:

-

1)

the assessment showed they did not need any of the approved security measures offered,

-

2)

a risk assessment showed that the offer or installation of measures would incur a health or safety risk to police staff or contractors hired to install the measures, or

-

3)

trial staff were unable to contact the victim after several attempts for an extended period of time.Footnote 14

The offer of participation followed an informed consent process and required the consent of both the occupier and owner.Footnote 15 Following consent, the District Coordinators sent a work order to approved contractors who then completed the installation work (sometimes over several visits). Last, the District Coordinators followed up with victims to check that the installation was completed satisfactorily.

Maintenance of standard service for the control group

During the trial, all burglary victims were to receive the standard service provided by police, so that the only difference between the trial groups was the intervention described above. Information collected by an independent research company as part of a process evaluation indicates that this occurred. Interviewed attending officers and SOCOs reported that all burglary victims received the same speed of service, investigative responses such as forensic evidence gathering, and burglary prevention advice. Administrative data confirmed no difference between groups in the average time between the offence being reported and the date of SOCO or attending officer’s attendance (median 1 day). When surveyed, intervention group victims were more likely than control group victims to recall police staff discussing ways to improve security with them (95.2%, 298 vs 62%, 198 respectively) [X2 (1, N = 632) = 100.8, p <.001, Cramér’s V = 0.4, 95% CI -39.3–-27.0%]. However, victims may simply be more likely to recall security advice when it is followed by the provision of security. If the control group were less likely to receive the standard burglary prevention advice, one would expect them to be less likely to act on it by installing their own security measures. But to the contrary, both groups were equally likely to report installing at least one security measure, and the control group was more likely than the intervention group to report installing new door locks, window stays and lights.Footnote 16

Coordination and quality assurance

The District Coordinators played a pivotal role in ensuring full implementation of the intervention and ensuring the quality of data required for its evaluation. They:

-

ensured all burglaries were assessed for eligibility,

-

ensured all intention-to-treat group burglaries were assessed for security needs and offered participation accordingly,

-

checked the assessments and records in NIA to ensure these were accurate and complete,

-

liaised with frontline staff, victims, and contractors, to coordinate the assessments and installations,

-

recorded all stages of the process for each burglary, from eligibility criteria through to the details of what was installed, when and the costs in a spreadsheet,

-

identified any health or safety risks, and

-

liaised with District staff to raise awareness of the trial and identify and mitigate any threats to its implementation, including any other planned burglary related initiatives that might interfere with the trial. No other large-scale burglary initiatives were undertaken in the study Districts during the first year of the trial, and any risk posed by short-term local initiatives (e.g. hotspot patrols) was also mitigated by our case-level randomisation, which ensured that control, ITT and intervention properties remained comparable in all respects other than the LLL intervention.

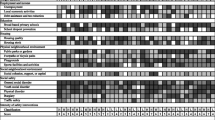

DailyFootnote 17 and weekly data reports from NIA acted as audit checks to identify any burglaries that may have been missed or updated since the initial report. Using this data, Weekly Performance Dashboards provided process measures for each stage of the process, to track eligibility, attrition, and timeliness.

Appendix B Technical details of the security measures

Table 4 provides details of the security measures installed.

Appendix C Power and sample size calculations

Minimum sample sizes for the primary outcome measure (revictimisation), for several scenarios ranging from optimistic to conservative, were determined by power calculations at the outset of the trial, and updated after a 2-week feasibility study that enabled more accurate estimates of the number of eligible properties and consent rates. Table 5 sets out calculations of the required sample size based on an optimistic effect size that the police considered would be operationally meaningful in terms of overall reductions in burglary considering targets set by the government at the time (New Zealand Police, 2019). This calculation thus reflected an effect size of practical, rather than theoretical, interest (Lakens, 2021). First, expected effectiveness was estimated as the 12-month revictimisation rate (proportion of victims revictimised) in the trial Districts, minus the proportion revictimised within a week of the original burglary (in case security was not installed in that period). From there, the expected effectiveness was further adjusted to reflect that fewer than 100% of future burglaries would be prevented by the security measures. The optimistic estimate meant a 5.0 percentage point difference when comparing the intervention and control group (i.e. 3.9% versus 8.9% revictimised), requiring 75% prevented, which was viewed as plausible considering the targeting of the security measures to the circumstances of the initial burglary. The minimum sample sizes in each group necessary to detect an effect of that size at 80% power was then calculated for optimistic and conservative consent rate scenarios, being the consent rate during the feasibility period of 95% (37 of 39 properties) and 90%, respectively.

Based on burglaries reported between 1 June 2017 and 31 May 2018 and the eligibility rate observed in the feasibility period, we estimated that 2,998 properties would be eligible in the year of the trial, exceeding the requisite sample size (n=828) for the optimistic scenario by approximately three times. If the effect size was halved (h=.1, or a 2.5 percentage point difference), this sample would be 93% and 90% of the requisite number at 95% and 90% consent rates respectively. Additional power calculations for an intention-to-treat comparison applying more conservative effect sizes and consent rates indicated that the trial would need to be extended beyond the first year to achieve a sufficient sample.

In the event, 2,614 properties were eligible in the first year, meaning that the present analysis risked Type II error (falsely accepting the null hypothesis of no difference) for the intention-to-treat comparison if the true effect was very small. This risk was acceptable for the purpose of the present analysis, conducted to inform decisions about the initiative, because there would be little practical difference between concluding the intervention was not effective or was so marginally effective as to not warrant its cost.

Appendix D Displacement analyses

Displacement measures

Table 6 shows the measures of displacement employed.

Analysis methods

To test for target and offence displacement, we compared pre-intervention and post-intervention monthly offence counts in the trial districts and a group of control districts, using controlled interrupted time series analysis (Lopez Bernal et al., 2018). This analysis was conducted using the R package MarketMatching (Larsen, 2016) which provides a user-friendly workflow drawing on the functions of CausalImpact (Brodersen et al., 2015) and dtw (Dynamic Time Warping, Tormene et al., 2009) packages. CausalImpact has previously been used to identify the effects of a crime focused intervention in a quasi-experimental study (Ratcliffe et al., 2017). The dynamic time warping analysis first identifies a set of control areas which best match the intervention area’s pre-intervention time series. The control time series are then fed to CausalImpact to construct a Bayesian structural time series model which produces a counterfactual prediction for the post-intervention period, i.e. the pattern predicted to have occurred had the intervention not been implemented. The observed (trial districts’) post-intervention time series is then compared to the counterfactual prediction. In our context, a divergence of the observed from predicted time series would indicate displacement (observed > predicted) or diffusion (observed < predicted). A 36 month pre-intervention time period was used, to enable seasonal patterns to be accounted for, consistent with previous research into seasonality in crime time series (Hipp et al., 2004; Linning et al., 2017).Footnote 18

Results

Consistent with there being no difference in revictimisation overall, we found little evidence of displacement. The only indication of displacement was that intervention group properties were significantly more likely to have near repeat burglary occur within 200m, though this effect was very small (Table 7, X2 (1, N = 2,306) = 5.6, p = .018). In light of the lack of a main effect and no 70m effect (Table 7), we treat this as a spurious result rather than evidence of displacement, in line with Groff and Taniguchi’s (2019a) approach to a similar result. There were no significant differences between groups indicative of MO displacement: 3-4% suffered a burglary outside or to an outbuilding; 1–2% suffered a burglary with an ineligible method of entry (Table 7). Analysis of the timing of repeat victimisations revealed no differences between groups in the number of days between the initial and subsequent burglary, suggesting no temporal displacement (Table 7).

The CausalImpact analysis showed no evidence of displacement to other types of crime. The time series for other burglary and other dishonesty offences per month during the trial period did not diverge outside the range predicted from the matched group of control districts. Table 8 presents the results of the matching process to identify control districts and CausalImpact analysis for each potential displacement crime type. As described in the table notes, several parameters were set to optimise the fit between the pre-intervention trial and matched controls’ time series. Fit was measured by the Durbin-Watson statistic (DW, a measure of autocorrelation in the residuals with an optimal value of 2) and Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE, with lower values better). The moderate levels of fit indicate that the matched districts were not perfect controls for the trial districts, requiring caution in their use as a counterfactual. Even assuming their appropriateness as controls, the analysis shows that the observed crime volumes did not deviate sufficiently from the counter-factual expected values to conclude that any target or crime type displacement occurred.

Figure 3 shows the expected and observed volumes of crime per month for each crime type. The steep drop in the top graph reflects a change in recording practice in April 2017. At no point during the trial period does the observed crime volume in the trial districts deviate outside the 95% confidence intervals of the expected values.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Curtis-Ham, S., Cantal, C. & Gravitas Research Ltd Locks, lights, and lines of sight: an RCT evaluating the impact of a CPTED intervention on repeat burglary victimisation. J Exp Criminol 19, 397–424 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-021-09494-7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-021-09494-7