Abstract

Objectives

This paper reports an evaluation of a police-led target-hardening crime prevention strategy inspired by research concerned with space–time patterns of burglary.

Methods

A total of 46 neighbourhoods in the West Midlands (UK) were randomly allocated to treatment and control conditions. Within treatment areas, resources were delivered to recent burglary victims and their close neighbours. Resources included inexpensive target-hardening measures as well as the delivery of dedicated police advice. The evaluation consisted of both a resident survey and a statistical outcome analysis.

Results

Results suggested that residents in treatment groups were slightly more satisfied with the police and more likely to have been contacted by the police concerning burglaries. Although they had more awareness of burglary, their fear of crime was not heightened. Statistical analysis suggested a very modest positive effect of intervention on crime and rates of re-victimisation. In particular, a survival analysis revealed that homes in low-crime treatment areas were less likely to be re-victimised than were those in similar control areas. Effects were more evident in low- than high-crime areas.

Conclusions

Results suggest that a low-intensity target-hardening intervention which adopted a near-repeat victimisation targeting strategy had a modest positive effect on residential burglary without increasing residents’ fear of crime.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Research concerned with repeat victimisation (RV) indicates that, when a home is burgled, there is a temporary elevation in the risk of subsequent burglary events at that property (e.g. Pease 1998). Research (e.g. Bowers and Johnson 2005; Johnson and Bowers 2004; Townsley et al. 2003) also suggests that the risk of burglary “spreads” to homes nearby shortly afterwards, producing patterns of what have been referred to as “near repeats” (Morgan 2000). The aim of Operation Swordfish, implemented by West Midlands Police (UK), was to use these findings to inform the implementation of a target-hardening intervention intended to reduce burglary. This paper reports the findings of an evaluation of that intervention. In the introduction to this article, we avoid a lengthy discussion of research concerned with repeat and near-repeat victimisation since this has been covered extensively elsewhere (e.g. Johnson et al. 2007). Instead, the aim of the introduction is to briefly situate the paper in the literature, outline the strategy implemented, and the approach to evaluation taken.

Approaches to reducing burglary are varied. Situational crime prevention (Clarke 1980) interventions aim to reduce victimisation risk by identifying vulnerabilities in potential crime targets, such as homes, and then manipulating the environment to make crime less likely. Such interventions include target-hardening, which involves the modification of the physical security of individual homes to make them more secure, or at least appear so. When implemented by the police, or other agencies, one challenge with such interventions concerns the question of who should receive the intervention and when. Informed by the empirical regularity that victims of burglary are at an elevated risk of further burglaries shortly after a first offence, Pease and colleagues (e.g. Forrester et al. 1988; Pease 1998) suggested that victimisation itself should trigger implementation, with burgled homes receiving intervention shortly after a crime occurs, so as to prevent further repeat offences at the same home. A series of evaluations of interventions based on this strategy have been conducted, and a recent meta-analysis concluded that they successfully reduce crime (Grove et al. 2012). Importantly, not only have they been found to prevent repeat victimisation, but they have also been found to reduce area level rates of crime more generally, suggesting that offender activity is not simply displaced by such intervention (see Johnson et al. 2014).

Interventions of the kind described focus on burglary victims. Inspired by the findings concerned with near repeat victimisation, in the current study, the intervention evaluated focused both on recent victims and their neighbours. As far as we are aware, there are currently no published evaluations of target-hardening interventions based on the prevention of near-repeat burglaries. Fielding and Jones (2012) implemented a police patrol strategy informed by the near-repeat phenomena, reporting it to reduce burglary by around 27%, but in that study police patrol—rather than target-hardening—was the key ingredient of the intervention. Other studies have also found police patrol strategies based on similar principles to reduce crime (Mohler et al. 2015; Santos and Santos 2015). In addition to their impact on crime, one concern with interventions—such as the one evaluated here—that make residents aware of the change to their risk of victimisation, is that this will increase their fear of crime. Consequently, we also examine this issue. Below, we describe the intervention implemented and the evaluation strategy in some detail, but, before doing so, we discuss pertinent issues associated with the evaluation of crime prevention interventions.

Challenges in evaluation

As has been discussed elsewhere (Campbell and Stanley 1963), a well-considered evaluation methodology is paramount for establishing a causal relationship between implemented interventions and their outcomes. Various approaches to evaluation exist, each with their own strengths and weaknesses. Three fundamental issues are worthy of discussion. The first concerns the estimation of the effect of intervention. Since one cannot actually know how much crime would have occurred in the absence of intervention, it is necessary to estimate this. As discussed by Campbell and Stanley (1963), various evaluation designs exist. Most involve some form of comparison between those who receive intervention and those who do not. Approaches to comparators vary, but one approach that has the advantage of reducing bias in their selection is random assignment. In this case, as the name suggests, treatment and control groups are selected at random. This approach has the advantage of minimising “selection bias”, which occurs if those selected are chosen on the basis of observed or expected trends that would make an intervention look favourable (or not). If done properly, randomisation serves to ensure that treatment and control groups are comparable on factors—measured or not—other than the intervention.

The second issue concerns the appropriate unit of implementation. In the case of target hardening interventions, one could offer the intervention to a random sample of victimised homes and their neighbours. A key assumption of randomisation is that everyone has an equal probability of being selected to receive the treatment, or of being allocated to the control group. In the case of the current intervention, this would be problematic, since the intervention is offered to both victims and their neighbours. As such, if treatment were offered to a neighbour of a victim, that home would subsequently be ineligible for assignment to the control condition if they were subsequently burgled, thereby compromising the integrity of the (random) allocation protocol. Moreover, just as the risk of crime is expected to diffuse in space in the absence of intervention, so too is the beneficial effect of treatment. That is, if crime is prevented at homes that receive treatment, so too is the spread of risk that would otherwise be expected to have occurred. Thus, homes near to those allocated to the treatment condition would be expected to enjoy the benefits of intervention, albeit indirectly. For this reason, in this study, we decided to use an area level rather than household unit of allocation, with victimised homes and their neighbours in the treatment areas receiving treatment and those in the control areas receiving crime prevention activity that reflected business as usual.

The third issue concerns what is actually implemented. This often goes unmeasured and evaluators instead take an “intention to treat” approach, which assumes that the intervention was implemented as planned. As the literature attests (e.g. see Knutsson and Clarke 2006; Sherman 2013), this is often an unreasonable assumption. An alternative approach is to explicitly monitor what happens, measuring the dosage of intervention (e.g. Bowers et al. 2004). In the current evaluation, we employ a randomised controlled design—allocating areas to treatment and control conditions—and explicitly measure the dosage of intervention.

Operation swordfish

The operation was implemented in the city of Birmingham, UK, over the 30-week period, 1 September 2012 to 16 March 2013. Birmingham is the second largest city in the UK in terms of both population (approximately 1.1 million) and area (268 km2), and is ethnically diverse. Levels of inequality, unemployment and deprivation are high, relative to the rest of the UK,Footnote 1 but its crime rate is relatively low in comparison to other major cities.Footnote 2 In addition, Birmingham has a high student population, particularly clustered in some areas.

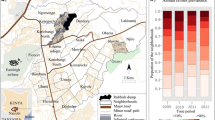

For Operation Swordfish, each of the 46 policing neighbourhoods (co-terminus with political wards) in Birmingham were randomly allocated to either a treatment or control condition. A map of these areas is shown in Fig. 1. The randomisation process was complicated, and a range of different approaches could have been used to define treatment and control groups. Ultimately, for each neighbourhood, the experimental unit was the portion of the neighbourhood lying within a 200-m internal geographical buffer of the neighbourhood boundary. This approach was taken to ensure that there was some physical separation between all areas involved in the trial, mitigating the possibility of interaction effects between (experimental and control) units.Footnote 3

As the sample size of experimental units (n = 23) was relatively small, a block randomisation procedure (with the burglary rate as the blocking variable) was used to ensure that the two groups (experimental and control) were matched in terms of their pre-intervention burglary rate. In the control areas, no treatment was implemented as part of the intervention and officers were instructed to police as usual. They were not told to avoid doing new things, and hence it is possible that they did (including the implementation of repeat victimisation prevention strategies). Furthermore, it is likely that officers in the control areas had at least some understanding of the strategies implemented in the experimental areas and so may have borrowed from them.

Treatments and interventions

In the treatment areas, when a burglary occurred, the victimised home and its eight immediate neighbours (four on either side) received a visit from officers and residents were given a simple target-hardening pack. This approach of intervening at nine households was adopted with the intention of preventing both repeat and near-repeat victimisation. This approach extends a “super-cocooning” tactic effectively implemented in earlier studies (Forrester et al. 1990), whilst not requiring excessive resources to implement. As noted above, research suggests that the risk of (near) repeat victimisation is elevated immediately after a burglary takes place, and hence visits were intended to take place as swiftly as possible. The households that were to be treated were identified using software developed by the UCL team. To explain, each day, the software imported the location of every new burglary that was reported to and recorded by the police. It then identified the addresses of the eight neighbouring properties that were to be treated, and allocated them a priority level.

In terms of priority levels and treatment received, burglary victims were given a “gold package”. This comprised LED units that shone light against the window creating the appearance of a television being on, electronic timers, door and window chimes, a crime prevention sticker, and details of neighbourhood watch schemes in the area. The four closest neighbours of victims received “silver packages” and their subsequent four neighbours received “bronze packages”. The silver packages contained the same items as the gold, but without LED units and stickers, and bronze packages were the same as silver but without door chimes. The sticker consisted of a silhouetted image of a guard dog to discourage opportunism. The sticker was intended to “nudge” offenders away from targeting the property and could be considered an ethical deception. The target-hardening was intended to increase offender perception of guardianship and the consequent risk of committing burglary. Regardless of priority level, all homes visited were also provided with information about how burglaries had recently been committed in their local area, so that they could consider addressing any vulnerabilities that local burglars appeared to be exploiting. Compared to other target-hardening schemes, the treatment was a low intensity (with equipment costs of around £12 per household on average) intervention, but the targeting strategy was highly focused and the implementation process actively monitored by police staff. The target-hardening equipment was funded by Birmingham’s Community Safety Partnership at an overall cost of £115,000. To measure dosage on a daily basis, West Midlands Police recorded which homes were visited and when, whether target-hardening was installed, if specific MO advice was given (i.e. regarding recent burglaries), and so on.

Implementation

In this experiment, a Chief Inspector was appointed to coordinate the implementation of the trial in the four local policing units that constituted Birmingham. All neighbourhood Sergeants and Constables were briefed by a police/UCL team, emphasising the importance of experimental integrity. This was turned into the ‘ten commandments of operation Swordfish’, including “thou shalt not steal the other teams’ target-hardening equipment” (for full details, see Online Appendix A). Each day, the target-hardening instructions were sent to the respective policing teams with explicit requirements regarding what needed to be completed and provision of confirmation that it had. Visits were completed by uniformed Police Community Support Officers (PCSOs).Footnote 4 Omissions in completions were re-tasked out. A secondary form of supervision consisted of officers physically checking addresses that had been noted as complete. The results of this checking were fed back to neighbourhood teams to encourage compliance. This sort of feedback has been found to be of great importance to the integrity of implementation in other West Midlands Police experiments (Slothower 2014). This level of monitoring is well above what is considered normal, and yet, as we shall see, compliance was still an issue. It is clear that one of the most significant challenges in policing is not necessarily “what works?” but “what happens”.

In April 2014 (approximately one year after implementation), the UCL team conducted a postal survey in the experimental and control areas. Survey respondents consisted of victims of burglary and their neighbours, and the aim of the survey was to examine how the intervention might have affected resident’s perceptions of the police, their everyday behaviour, and their crime reporting behaviour, and to get a sense of what might have been implemented in the control areas that we were not aware of.

In what follows, we first describe the methodology used, and present the findings of the sample survey. Next, we present analyses of police recorded crime data to assess the impact of the intervention on levels of crime. It was deemed important to outline the survey results first, as they might reveal patterns in implementation that should be considered when interpreting the findings of the outcome analysis.

Methods and results

Sample survey

A 25-item (including branching questions) questionnaire (see online Appendix B) was developed for residents who either received the intervention, or would have done so if they had lived in one of the treatment areas (these acted as the control group). The questionnaire included items concerning their recent victimisation experience; their satisfaction with, and likelihood of, reporting crime to the police; whether they had been visited by the police following their most recent burglary (if relevant); and whether they had been provided with a crime prevention “kit” or given crime prevention advice.

Prior to conducting the survey, statistical power calculations were conducted to determine how many surveys would need to be returned to enable us to detect a given difference between the treatment and control groups for the analysis of a contingency table. Given that the expected distributions were unknown (there was no prior expectation about how people might respond to the questions across the two groups), we examined what size of sample would be needed to detect a 0.1 difference (a 10% difference in opinion) for a 2 × 2 contingency table. This indicated that a sample size of 400 would be sufficient.

Prior research (Shih and Fan 2008) suggests that the typical response rate for postal surveys is about 45% (range 10–89%). However, the Shih and Fan (2008) study examined response rates for published studies, and those for unpublished studies may be lower. Further, it might be the case that response rates differ across treatment and control groups. Consequently, we assumed a fairly conservative response rate of 20%. On this basis, we estimated that surveys would have to be distributed to a total of 2000 respondents to generate the necessary sample. To encourage response rates, in accordance with advice given by Edwards et al. (2002), we offered an incentive to respondents in the form of participation in a raffle (with an iPod as a prize), minimised the length of the questionnaire, and indicated on the postal envelope that the survey was being conducted by a University.

Procedure

Survey questions were designed by a team of three academics and were loosely based on questions from the Crime Survey of England and Wales (see, e.g., Jansson 2007 for a review). A total of 2016 surveys, each with an accompanying covering letter and a return (post-paid) envelope, were posted to a sample of homes, consisting of burglary victims and their neighbours, selected randomly from the available sampling frame. A total of 672 surveys were sent to households that had been burgled in the experimental and control areas (336 in each type of area). A further 1344 surveys were sent to the neighbours of burglary victims that did, or in the case of the control group, would have received either bronze or silver treatments (672 in each type of area). This was to ensure that we sampled similar numbers of respondents that were (or would have been in the case of the control groups) allocated to the gold, silver and bronze conditions. All survey responses were transcribed by a research assistant, and a random sample cross-checked by a member of the research team. All responses were coded exactly as they were written and unanswered questions were left as blank cells.

Sample

A total of 246 residents completed the survey—132 from the treatment group and 114 from the control group. Since there were a possible 1008 responses in each group, these constitute response rates of 13% and 11%, respectively, and an overall rate of 12%. This indicates a very slightly higher response rate for the treatment group. Not all respondents answered each question. In what follows, those who did not answer a particular question are excluded from the analyses of the results for that question, but the total number of respondents who did reply is reported in each case.

Survey results

Police contact

Around 80% of respondents from the treatment group and 60% from the control group reported being contacted by the police in the last 12 months (regardless of whether they had been a victim or not) to provide them with crime prevention advice. Respondents from the treatment group were more likely to report that they had been contacted by the police than those in the control condition and the difference was statistically significant (n = 152; X 2(1) = 5.02, p = 0.03).

Awareness of burglary

To prevent repeat and near-repeat victimisation, one aim of the intervention was to raise residents’ awareness of burglaries in their area (but without increasing their fear of crime). Consequently, survey respondents were asked if they were aware of burglaries that had occurred in their neighbourhood within the last 12 months. Those in the treatment area (58%) were slightly less likely to be aware of burglaries in their area than were those in the control areas (68%), although the difference was non-significant (n = 246; X 2(1) = 2.10, p = 0.14). For those who were aware of a burglary in their neighbourhood, responses suggested that, in the treatment areas, residents were more likely to have been told about this burglary by the police (80%) than those in the control areas (60%), (n = 246; X 2(1) = 5.01, p < 0.05).

As well as being asked if they had been contacted by the police about a burglary in their neighbourhood, respondents were also asked if they had been provided with further information about the offence(s). Results suggest that respondents in the treatment area (60%) were more likely to have been provided with additional information about a burglary in their area than those in the control areas (25%) (n = 151, X 2(1) = 16.9, p < 0.001).

Respondents who were aware of burglaries in their area were also asked if they had been apprehensive about being burgled after the crimes concerned. Respondents were more likely to be apprehensive than they were not (approximately 70% of both groups), but there were no differences in reported apprehension for those in the treatment and control areas (n = 156 X 2(1) = 0.01, p = 0.91). Finally, respondents who were aware of burglaries in their area were also asked if they were aware of an increased police presence immediately after them. Results suggest that most were not. The small difference observed between groups (70% unaware in the treatment and 82% in the control) was not statistically significant (n = 157; X 2(1) = 2.39, p = 0.12).

To summarise, respondents in both the treatment and control areas were equally likely to claim to be aware of recent burglaries in their neighbourhoods. Those in the treatment areas reported that they were more likely to have learned about such offences from the police and to have been given more information about the offences than just that they had simply taken place. Respondents reported being apprehensive following burglaries in their areas, but, despite those in the treatment area being contacted by the police and being provided with more information, they were no more apprehensive than those in the control areas. One interpretation of this finding is that (on the basis of the current sample of data) it appears that providing residents with information about recent burglaries is unlikely to increase their fear of crime. This early indication is important, as fear of crime is often cited as a reason for not communicating specific information to potential victims (e.g. Winkel 1991). In light of reduced resources, it could be argued that informing and mobilising the citizenry is more important than ever. If crimes predict future crimes, as Johnson and Bowers (2004) show is the case for burglary, it is imperative that residents are informed not only of the crime type but also the modus operandi. Further, our results suggest that they can be informed of what can be successful in combatting repeat/near-repeat victimisation without experiencing a backfire by way of fear of crime.

In terms of implementation fidelity, the conclusions appear to be mixed. That is, while those in the treatment area appear to have received most of their information about burglaries from the police, if all respondents in the treatment area had been contacted about burglaries at neighbouring addresses (as intended), then those in the treatment areas would have had greater awareness of recent offences than those in the control areas. They should also have been aware of more police presence in the area, which was not the case here. This suggests that not all homes may have been visited. However, a few caveats are necessary. First, respondents were only asked if they were aware of burglaries that occurred in the last 12 months. In some cases, burglary offences of which they were aware may have occurred post intervention. Second, some burglaries of which respondents were aware may not have been reported to the police. And third, it is possible that while a survey respondent may not have been contacted about recent offences, another member of the household might have been.

Likelihood of reporting crime

Figure 2 shows that the likelihood of a respondent claiming that they would report a burglary to the police was high, regardless of condition. The small difference apparent was non-significant (n = 244; X 2(4) = 8.26, p = 0.08).

Levels of satisfaction with the police

Figure 3 shows reported levels of satisfaction with the police for the treatment (n = 130) and control (n = 111) groups for those who answered this question. Relative to the control group, a higher proportion of those in the treatment areas indicated that they were either fairly or very satisfied with the police (70% in the treatment group and 57% in the control group). Thus, while the overall difference observed across the five categories shown in Fig. 3 was not statistically significant (X 2(4) = 4.84, p = 0.31), the difference in those that expressed that they were either fairly or very satisfied with the police (versus those that were not) was (X 2(1) = 3.99 p < 0.05).

Who is responsible for crime control?

When asked who they felt were responsible for preventing crime, most respondents (around 75%) felt that this was the responsibility of the police and residents (see Online Appendix C). Fewer than one-third of respondents felt that the local authority had such a responsibility. None of the differences between the two groups was statistically significant.

In summary, for the sample obtained, those in both the treatment and control groups were highly likely to report an incident to the police. It appears that those in the treatment groups showed slightly higher levels of satisfaction with the police, presumably because they felt the police had invested time in discussing incidents and prevention with them. However, differences between groups were quite modest. Respondents in both groups thought residents and police were most responsible for prevention, with more in the treatment group naming the police (vice versa in the control group). Again, differences were small.

Police recorded crime data analysis

In this section, we examine the outcomes of Operation Swordfish in terms of changes in levels of recorded crime. In doing this, we test for effects at two levels—that of the individual houses that received treatment and that of the treatment areas as a whole. If the treatment was successful, we might plausibly expect effects at both these levels. To explain, the idea of the strategy is to secure not only victimised homes (thereby reducing repeat victimisation), but also potential future targets of burglary in the form of burglary victims’ neighbours. If implemented with sufficiently high levels of intensity, this could lead to offenders avoiding entire street segments. It is also possible that the intervention could lead to the geographical displacement of offender activity within the treatment areas, or a diffusion of crime control benefit (see, e.g., Guerette and Bowers 2009). We return to this issue later. For now, we begin by looking at the individual effects on those homes that were directly in receipt of the treatment implemented to see if and how rates of repeat victimisation were affected.

Repeat victimisation

To examine the direct influence of the intervention on the homes treated—burgled homes and their immediate neighbours—we examine the likelihood of subsequent victimisations and the time to victimisation following treatment for those households that received (or would have had they not been in the control areas) target-hardening. That is, we consider how much time elapsed between the burglary that triggered intervention at treated households (and their neighbours) and any subsequent burglaries. We then perform a survival analysis to see if the observed patterns differ for homes in the treatment and control areas.

To generate data for the comparison group, we performed an artificial run of the Swordfish software on the real crime data for the control areas during the experimental period, that is, we found which properties would have been treated had Swordfish been operational in those areas. Comparing the time to re-victimisation for these properties with that for their counterparts that actually received treatment enables us to estimate the effect of treatment.

In terms of treated households, a spreadsheet was maintained by each police area during the course of implementation. Data were available for 5140 household treatments, of which 648 represented gold treatments, 2395 were silver, and 2097 were bronze treatments. Data for some trigger events (burglaries that occurred in the treatment areas that initiated treatment) were not provided or were unsuitable for analysis. In some cases, this was due to recording issues encountered at the beginning of the treatment period (83 burglaries), while some missing data appear to be due to a drop in recording towards the end of the intervention period. In other cases, data were simply incomplete insofar as we could not confirm that the addresses were treated even though they qualified for assistance (259 burglaries). Here, the software prescribed treatment but there was no record in the dosage spreadsheet, and we can assume that either treatment was not given or that it was given and not recorded. To assess the effect of these situations, the analysis described below was also run with this broader intention-to-treat subset, but since we found no substantial differences for this analysis, these results are not discussed any further.

Police recorded crime results

We first compare survival rates for all treated properties, no matter what the level of treatment. Of the 5140 prescribed treatments, 166 properties were re-victimised by the end of the observation period, compared to 260 in the control group. The survival times for these are shown in Fig. 4, in which the vertical axis indicates the proportion of properties that had not been victimised x days after the trigger burglary that instigated the treatment. The plot shows the survival curves for each group, along with bands representing 95% confidence intervals in each case (for details of their calculation, see Kalbfleisch and Prentice 2002). Visual inspection suggests that burgled homes (that would have been treated) in the control group were more likely to be re-victimised than target-hardened homes in the treatment group (the green line showing treatment group survival remains above the blue line for the control group), such that, by the end of the evaluation period, fewer homes had been re-victimised in the treatment group. The difference in survival rates appears to be greatest around 1.5 years post-intervention. However, a formal analysis showed that the difference in the two distributions was not statistically significant (p = 0.39).

It is possible that the treatment effect might also depend on the type of area in which measures are implemented (see Pawson and Tilley 1997). Since the treatment and control areas were matched on most factors through the process of randomisation, we consider here if the effects differ by the rate of burglary, a factor that, as mentioned above, we matched across groups through the blocking manipulation (rather than simple randomisation). To do this, in Fig. 5, the plot on the left shows the survival curves for homes in the 50% of areas with the highest burglary rates, while that on the right shows them for those with the lowest. This shows the same trend as that observed in Fig. 4, but the effect appears to be larger in the low-crime areas. In this case, the survival curve for the treatment group is outside of the confidence intervals for the control group, and the effect is only marginally non-significant (p < 0.10). In the high-crime areas, the effect is non-significant (p = 0.90).

Treatment groups and moderators

In what follows, we examine these patterns in a little more detail by looking at the “survival” curves for homes that had been burgled and had received the gold intervention (or would have if they had been in the treatment group) and those for their neighbours (silver and bronze treatments). Figure 6 shows the survival curves for properties assigned to gold treatment. There appears to be a positive treatment effect for homes in the high-crime areas, but not in the low-crime areas (the survival lines show the reverse pattern). However, the differences are not statistically significant, and it is important to note that the number of homes included in this analysis is low (n = 318 for the high-crime areas, n = 152 for low-crime), making the analysis less reliable.

In the case of neighbours of burgled homes (that is, those in the bronze or silver treatment groups), there appears to be little effect in the high-crime neighbourhoods (Fig. 7, left), but in the neighbourhoods with the lowest burglary rates (Fig. 7, right), there does appear to be a preventative effect, and this is statistically significant (p = 0.002).

In short, the intervention overall did not have a significant effect on survival rates. In separating by area, it would appear that there was a (marginally non-significant) trend that suggested that across all treated houses burglary dropped in the low-crime areas. Looking at the effects by level of treatment, there was no effect for gold group households, but in the case of the neighbours of victims (silver and bronze groups), the risk of burglary victimisation was reduced in the lower-crime neighbourhoods and this effect was statistically significant.

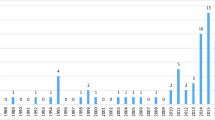

Time series

In this section, we examine trends at the area level. We use time series data to do this because—unlike interventions such as a hotspots policing initiative—the intervention was implemented gradually over a large area over time. Figure 8 shows a time series plot of the total number of completed recorded burglaries (aggregated) across the treatment and control areas per week. Implementation intensity was measured in two ways. In the first instance, we use the number of incidents that were flagged as requiring treatment, regardless of whether treatment was actually recorded. This is a measure of intention to treat and does not necessarily reflect the number of homes which actually received the intervention. The dotted line represents a cumulative measure of this type of intervention intensity, indicating that implementation increased steadily over a period of 27 weeks. Looking at Fig. 8 it is difficult to determine if there was an effect of intervention. Consequently, we conducted a formal time series analysis to see if—after controlling for other factors (measured and estimated)—there was an association between the weekly count of burglary in the treatment areas and the cumulative dosage of intervention. To test this, the simplest model that could be employed would be an Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression. For such a model, we could regress the weekly count of burglaries in the treatment areas against that in the control areas, and the cumulative estimate of intervention dosage. However, a problem with analysing time series data using OLS regression is that an assumption of the test—that the observations are independent—will generally be violated (as is the case here). Consequently, we use more formal time series analyses.

A number of time series model specifications are possible. Autoregressive (AR) terms account for the fact that the value of a series at one time point is a function of those immediately before, and hence that observations are not independent. Moving average (MA) models measure the effect of stochastic shocks in a time series on future observations and then account for these, while ARCH models can be used to deal with the fact that the error associated with a model may vary across the time series (heteroskedasticity). To ensure that any conclusions were not sensitive to model specification, we tested all possibilities, starting with ARCH models.

Table 1 shows that while the ARCH term was not significant, the AR (up to two lags but not more) and MA terms were. In all cases, after controlling for the trend observed in the control areas, there was a negative association between recorded burglaries and the cumulative intensity of intervention. That is, as more homes were treated, on average the weekly count of burglary in the treatment areas appears to have decreased relative to the trend observed in the control areas. However, two issues are important to note. First, the estimated effect was relatively small, suggesting a reduction of about 6 burglaries per week for every 1000 homes that had triggered treatment. Second, in the case of the ARMA model, this association was marginally non-significant (with a p value of 0.072, two-tailed).

The second type of intervention intensity modelled was the total number of homes (burgled homes and their neighbours) that were recorded as having actually received the intervention. The analyses presented above were repeated using these data (see Online Appendix D) and revealed an identical pattern of results.

In summary, for all models estimated, the association between the weekly count of burglaries in the treatment areas and the cumulative intensity measure was in the right direction. In other words, as more homes were treated in the intervention areas, on average the weekly count of burglary appears to have decreased relative to the trend observed in the control areas (after accounting for the dependency in the data). However, as the intervention coefficient for the ARMA (1,1) model was marginally non-significant (see Table 1 and Online Appendix D), caution should be exercised when interpreting the results.

Discussion

This study examined the impact on burglary of Operation Swordfish, a target-hardening intervention intended to prevent repeat and near-repeat victimisation. During the period of implementation, in the treatment areas, burglary victims and their neighbours were offered crime prevention advice and a crime prevention kit, including electronic timers, door chimes and window stickers. In the control areas, victims and their neighbours received the usual response, which could, of course, include similar activity.

A postal survey was used to examine resident satisfaction with the police response to crime and to see if and how this differed across treatment and control areas. It appears that those treated showed slightly higher levels of satisfaction with the police, presumably because they felt the police had invested time in discussing incidents and approaches to crime prevention with them. However, differences between groups were modest. In terms of interaction with the public, in both areas, respondents reported that the police had contacted them about recent burglaries in their neighbourhood, but that this was more likely in the treatment areas. Important to future exercises, being provided with specific information about burglaries by the police did not appear to affect levels of apprehension about the future risk of crime. An increase in the fear of crime is often cited as a potential consequence of intensive policing activity, or police contact, but there is no evidence of this here. There were no differences between the two groups (treatment and control) in terms of whether respondents felt that there was an increased police presence in their area following burglaries, or in terms of the extent to which they would report a future crime to the police. These findings may suggest that the intervention was implemented as planned, but perhaps not as consistently as intended. As a caveat, the response rate for the survey was relatively low. This is common for postal surveys, but future studies might explore alternative strategies to improve response rates.

A useful and unusual feature of the data that were collected in this evaluation was the documentation of actual visits to individual properties as part of the intervention. The measurement of crime prevention ‘intensity’ is still rare in such studies (see Bowers et al. 2004 for more details on measuring activity). The advantage of it is that it distinguishes between an intention to treat and actual treatment of individual properties. It is apparent that collecting even more detailed information on this element will provide more nuanced evidence-bases in the future. For example, it might be that residents in the treatment area were not able to detect an increased police presence in the area because of a mismatch between the timing of patrol and their own routine activities. Without precise information on time of visit (rather than just day of visit) and, ideally, on the routine movements of residents, this is difficult to test empirically. However, the information on the precise location of treatment did make it possible to test the effect of the intervention at both the individual household and areal level.

Considering the impact of intervention, it would appear that there is some evidence of a positive effect of intervention. In particular, as mentioned above, relative to the control group, survey respondents from the treatment group were more likely to be fairly or very satisfied with the police than those in the control group. While burglary victims in the high-crime areas were not found to experience a statistically significant reduction in risk, in the low-crime areas, there was a clear (albeit marginally non-significant) trend to suggest an effect of intervention. Furthermore, in the lower-crime areas, the neighbours (who received intervention) of burgled homes experienced a statistically significant reduction in risk.Footnote 5 It is important to note that, while this effect was reliable, it was small. In terms of effects at the area level, time series analyses suggested that (after estimating the effects of unobserved influences) relative to the trend observed in the control areas, crime reduced in the treatment areas. Again, this effect was small and, for the ARMA model, was only statistically significant using a one-tailed test.Footnote 6 Detecting an area level effect for an initiative which concentrated on specific households is in itself of interest, however small. It implies that, in the worst case, any positive effect experienced by the neighbours of victimised homes was not displaced elsewhere within the local area. Had offenders deflected from the treated homes in question just settled on the nearest non-treated household(s), it is unlikely that any overall area effect would be detectable. This demonstrates that there is value in testing effects at different areal units. It also falls in line with systematic review evidence on the displacement of crime following both situational interventions (Johnson et al. 2012) and focused policing efforts (Bowers et al. 2011), which have concluded that, on balance, there is no evidence that crime problems are simply shifted to other areas.

Operation Swordfish was a simple intervention involving the delivery of target-hardening and tailored crime prevention advice to victims and their neighbours. However, delivery of the intervention did require the presence of a police community support officer who, when present, could act as a capable guardian. Consequently, disentangling what it was that produced the small but positive effect observed is important. The survival analysis presented suggests that the effect of intervention endured for some time. This contrasts with, (often) more short-term, hot-spot patrol initiatives for which the effects tend to be larger (e.g. Braga et al. 2015) but persist for only a short time after they are withdrawn (e.g. Sherman 1990). Consequently, it seems reasonable to suggest that, in the current study, it was either the target-hardening that produced the modest effects observed or the tailored advice provided. Considering the target-hardening, as discussed, this varied across households with some receiving more items than others, according to their estimated risk. The survival analysis suggested that those receiving different levels of target-hardening benefited. Thus, from the current study, it is not possible to determine whether the effect of intervention was attributable to the advice given, the target-hardening, or a combination. Further, it has been impossible to disaggregate the impact of each target-hardening device. For example, the impact of the sticker with a guard dog on it may have had the same impact as the artificial television—but with significantly different costs. Future work might seek to estimate which mechanisms and combinations are most likely to reduce crime and how this might be amplified.

The findings of the study are therefore in the right direction, but small and not consistently statistically significant. This is perhaps not surprising given that the intervention was inexpensive (target-hardening equipment that is installed often costs hundreds of pounds or more, but costed around £12 here) and relied on residents using the equipment supplied. To elaborate, Grove et al. (2012) showed that the success of repeat victimisation strategies is positively associated with the intensity of implementation. Moreover, it appears that interventions that rely on resident action are less likely to succeed than those that do not (see, e.g., Knutsson and Clarke 2006). There are further potential issues with implementation fidelity. For example, it was noted above that, for 259 burglaries of 907 prescribed for treatment, there was no clear record of police visitation. This equates to 29% of the potential treatment group. However, visitation to the remaining 71% and their neighbours represents a substantial effort, particularly as residents may have been out at the time officers were able to visit. In the future, perhaps one method of increasing the number of visits to victimised homes would be to reduce the number of treatments offered to their neighbours in order to reduce the personnel resource required per burglary. This may mean that more victims’ homes could be revisited to ensure that contact is made. Put differently, a balance may need to be struck between the number of victims and the number of their neighbours that can be visited.

In future studies of this kind, it would also be useful to complete more detailed recording and analysis of what happened where and when on the ground. The advent of body-worn video cameras and operation rooms concerned with activity, as well as dispatch, could assist in this respect. This in turn could inform what in particular might be effective. We demonstrated above, for example, that there might be differential effects in different types of area, and that measures might be more effective for neighbours of burgled homes than for the victims themselves. Further research could unpack such findings. For example, it might be that the positive effects found for neighbours in low-crime areas could be due in part to this group’s ability to fund and arrange further target-hardening once informed of an increased risk. In the case of repeat victimisation interventions, it is evident that celerity matters—measures should be implemented as soon as possible following initial events. If detailed information on the timing of treatments had been recorded in the current study, we could have looked for evidence of this. Future research might examine whether certain types of measure or certain types of advice are more effective. Recent evaluation research suggests that knowing these contextual variations is crucial to the implementation of well-informed treatments in specific places (Johnson et al. 2015).

Finally, it would be useful to track what had happened in areas deemed to be ‘control’ zones. Whilst the evaluation was designed to ensure physical separation between treatment and control areas, given the scale of the experiment, there is a reasonable possibility that the same personnel might have been active in both areas. As such, it is possible that there could have been treatment ‘contamination’ in the control zones. Moreover, while the use of a random allocation strategy will have reduced allocation bias, it does not prevent those in the control areas from purposefully mirroring what was done in the treatment areas, or trying other forms of intervention. Nevertheless, while we cannot be sure of the extent to which this might have occurred, the fact that our survey showed a difference in experience between treatment and control areas suggests that it was not sufficient to undermine the study.

Assuming that nothing changes in the control areas is an “intention not to treat” design. It was beyond the scope of the current study to detail what happened in the control areas, but this issue requires consideration in future work. Future experiments might actively construct monitoring mechanisms in both test and control areas for this purpose. As noted above, this might involve the use of body-worn video (Ariel et al. 2016), with a sampling regime of the video evidence used to test for experimental fidelity in real-time. An appropriate cycle of feedback regarding implementation (e.g. Slothower et al. 2015) might then help to reduce contamination between test and control groups.

Notes

See: https://www.birmingham.gov.uk/downloads/file/4561/2011_census_initial_findingspdf. Last accessed 6/7/2017.

https://www.police.uk/west-midlands/BW01/performance/compare-your-area/. Last accessed 6/7/2017.

As discussed, an alternative experimental design would have been to use burgled homes as the unit of allocation, with victims being randomly allocated to treatment and control conditions. In addition to the problems discussed above, simulation experiments showed that such an approach would have reduced statistical power (the ability to observe an effect on crime if one exists). Moreover, using such a design, it would not have been possible to estimate the effect of intervention at the area level net of any displacement or diffusion of benefit.

In England and Wales, PCSOs do not have powers of arrest, but are uniformed civilian members of police support staff whose role is to deal with minor offences and to help to prevent crime.

It is worth noting that a larger sample of neighbours received intervention than did burglary victims. This provides greater statistical power and may explain why an effect was reliably detected (for p < 0.05, two-tailed) for the neighbours of victims, but not for the victims themselves.

Since the expected direction of the effect was known, this is not unreasonable, but a two-tailed test provides a stricter test of hypotheses.

References

Ariel, B., Sutherland, A., Henstock, D., Young, J., Drover, P., Sykes, J., Megicks, S., & Henderson, R. (2016). Report: Increases in police use of force in the presence of body-worn cameras are driven by officer discretion: A protocol-based subgroup analysis of ten randomised experiments. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 12(3), 453–463.

Bowers, K. J., & Johnson, S. D. (2005). Domestic burglary repeats and space-time clusters: The dimensions of risk. European Journal of Criminology, 2(1), 67–92.

Bowers, K. J., Johnson, S. D., & Hirschfield, A. (2004). The measurement of crime prevention intensity and its impact on levels of crime. British Journal of Criminology, 44(3), 1–22.

Bowers, K. J., Johnson, S. D., Guerette, R., Summers, L., & Poynton, S. (2011). Do geographically focussed police initiatives displace crime or diffuse benefits? A systematic review. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 7(4), 347–374.

Braga, A. A., Welsh, B. C., & Schnell, C. (2015). Can policing disorder reduce crime? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 52(4), 567–588

Campbell, D. T., & Stanley, J. C. (1963). Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for research. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Clarke, R. V. (1980). Situational crime prevention: Theory and practice. British Journal of Criminology, 20, 136–147.

Edwards, P., Roberts, I., Clarke, M., DiGuiseppi, C., Pratap, S., Wentz, R., & Kwan, I. (2002). Increasing response rates to postal questionnaires: Systematic review. British Medical Journal, 324(7347), 1183.

Fielding, M., & Jones, V. (2012). ‘Disrupting the optimal forager’: Predictive risk mapping and domestic burglary reduction in Trafford, greater Manchester. International Journal of Police Science & Management, 14(1), 30–41.

Forrester, D., Chatterton, M., Pease, K., & Brown, R. (1988). The Kirkholt burglary prevention project, Rochdale. London: Home Office.

Forrester, D., Frenz, S., O’Connell, M., & Pease, K. (1990). The Kirkholt burglary prevention project: Phase 2, Crime Prevention Unit Paper no. 23. London: Home Office.

Grove L. E., Farrell, G., Farrington D. P., & Johnson S. D. (2012) Preventing Repeat Victimisation: A Systematic Review. Stockholm: Bra - The Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention.

Guerette, R. T., & Bowers, K. (2009). Assessing the extent of crime displacement and diffusion of benefit: A systematic review of situational crime prevention evaluations. Criminology, 47(4), 1331–1368.

Jansson, K. (2007). British crime survey-measuring crime for 25 years. London: Home Office.

Johnson, S. D., & Bowers, K. J. (2004). The burglary as clue to the future: The beginnings of prospective hot-spotting. European Journal of Criminology, 1(2), 237–255.

Johnson, S. D., Birks, D., McLaughlin, L., Bowers, K. J., & Pease, K. (2007). Prospective mapping in operational context. Home Office online report 19/07. London: Home Office.

Johnson, S. D., Bowers, K. J., & Guerette, R. (2012). Crime displacement and diffusion of benefits: A review of situational crime prevention measures. In B. Welsh & D. Farrington (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of crime prevention. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Johnson, S. D., Guerette, R. T., & Bowers, K. J. (2014). Crime displacement: What we know, what we don’t know, and what it means for crime reduction. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 10(4), 549–571. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-014-9209-.

Johnson, S.D., Tilley, N., & Bowers, K.J. (2015). Introducing EMMIE: An evidence rating scale to encourage mixed-method crime prevention synthesis reviews. Journal of Experimental Criminology, forthcoming.

Kalbfleisch, J. D., & Prentice, R. L. (2002). The statistical analysis of failure time data. Hoboken: Wiley.

Knutsson, J., & Clarke, R. (Eds.). (2006). Crime Prevention Studies (Vol. 20). New York: CRC.

Mohler, G. O., Short, M. B., Malinowski, S., Johnson, M., Tita, G. E., Bertozzi, A. L., & Brantingham, P. J. (2015). Randomized controlled field trials of predictive policing. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 110(512), 1399–1411.

Morgan, F. (2000). Repeat burglary in a Perth suburb: Indicatory of short-term and long-term risk? In G. Farrell & K. Pease (Eds.), Repeat victimisation: Crime prevention studies, 12 (pp. 83–118). Monsey: Criminal Justice Press.

Pawson, R., & Tilley, N. (1997). Realistic Evaluation. London: Sage.

Pease, K. (1998). Repeat victimisation: Taking stock. Crime prevention and detection series paper 90. London: Home Office.

Santos, R. G., & Santos, R. B. (2015). Practice-based research ex post facto evaluation of evidence-based police practices implemented in residential burglary micro-time hot spots. Evaluation Review, 39(5), 451–479.

Sherman, L. W. (1990). Police crackdowns: Initial and residual deterrence. Crime and Justice, 12, 1–48.

Sherman, L.W. (2013). Targeting, Testing and Tracking Police Services: The Rise of Evidence-Based Policing, 1975-2025. Crime and Justice, 42, 377–451.

Shih, T., & Fan, X. (2008). Comparing Response Rates from Web and Mail Surveys: A Meta-Analysis. Field Methods, 20(3), 249–271.

Slothower, M. (2014). Strengthening police professionalism with decision support: Bounded discretion in out-of-court disposals. Policing, 8(4), 353–367.

Slothower, M., Sherman, L. W., & Neyroud, P. (2015). Tracking quality of police actions in a victim contact program: A case study of training, tracking, and feedback (TTF) in evidence-based policing. International Criminal Justice Review, 25(1), 98–116.

Townsley, M., Homel, R., & Chaseling, J. (2003). Infectious burglaries: A test of the near repeat hypothesis. British Journal of Criminology, 43, 615–633.

Winkel, F. M. (1991). Police communication Programmes aimed at burglary victims: A review of studies and an experimental evaluation. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 1, 275–289.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank West Midlands Police, Birmingham City Council Community Safety Partnership and Inspector Clive Bayton. They would also like to thank Miranda Simon for her assistance with the survey.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Online Appendix A

(DOCX 19 kb)

Online Appendix B

(DOCX 27 kb)

Online Appendix C

(DOCX 18 kb)

Online Appendix D

(DOCX 19 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Johnson, S.D., Davies, T., Murray, A. et al. Evaluation of operation swordfish: a near-repeat target-hardening strategy. J Exp Criminol 13, 505–525 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-017-9301-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-017-9301-7