Abstract

Retirement of cultivated croplands creates potential for ecosystem and wetland restoration, but vegetation and soil legacies of cropping influence the development of post-agriculture vegetation. In low-lying coastal watersheds of southeastern Massachusetts, cranberries (Vaccinium macrocarpon Aiton) are cultivated in commercial farm units that are diked, leveled and sanded beds created from historic wetlands. Current low cranberry prices and expanding cranberry production elsewhere now increase the likelihood of cranberry farmland retirement. We quantified the trajectories of plant species richness and cover, and plant characteristics (life form, native or non-native, wetland or non-wetland) in a chronosequence of cranberry farm beds that ranged from cultivated units to those retired from cropping and revegetated for 90 years with no post-cropping management. Species richness increased from active beds to 10–20 year-old beds and subsequently decreased. Post-retirement species richness was overwhelmingly dominated by native species. Shrub and tree richness and cover increased steadily over time. The richness of wetland, upland and facultative species all increased quickly after retirement and then declined in the oldest retired beds. The basal area and canopy cover of red maple (Acer rubrum) and pitch pine (Pinus rigida) increased over time. Vegetation followed a relatively consistent successional trajectory and the plant community after five to nine decades was predominantly forest and dominated by non-wetland plants. Encouragement of long-term persistence of greater diversity and cover of wetland plant species on retired cranberry farms will likely require active hydrological and soil modifications that decrease sand depth and raise water tables.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Cessation of crop cultivation on agricultural lands initiates changes to the succession and composition of vegetation that develop over many decades. These changes are often initiated by shifts in farming practices caused by human migration, industrialization, expanded trade or increased opportunities for crop specialization. For example, expansion of rail and barge transportation from the Midwest to the Northeast U.S. in the middle of the nineteenth century contributed to the widespread abandonment of farmland and subsequent regrowth of forest (Whitney 1994). More recent contractions of farmland have resulted in expansion of forests in Europe, Central and South America, the Caribbean and other locations (Keenan et al. 2015; Chazdon et al. 2000; Grau et al. 2003). Future retirement of farmlands presents opportunities for restoration of historic or target plant communities.

In many locations, the unmanaged reestablishment and succession of vegetation results in plant communities that resemble those in the original vegetation (Foster 1992). In other cases, a history of agriculture results in the establishment of vegetation that differs from pre-agricultural vegetation (Motzkin et al. 1996; Foster et al. 2003; Cramer et al. 2008). In some cases, full recovery of species richness takes many decades or centuries (Dupouey et al. 2002; Rozendaal et al. 2019). Differences in trajectory are caused by changes to soils that create conditions unfavorable to original native plant species (Huennecke et al. 1990; Kulmatiski et al. 2006), changes to the water table and hydrology (Leppa et al. 2020), introduction of new and often non-native plants (Brown and Boutin 2009; Kuhman et al. 2011) or barriers to plant recruitment (Bellemare et al. 2002). In some cases, even subtle legacies, such as increases in soil pH, continue to influence plant communities after agriculture has ceased (Neill et al. 2007). Understanding the effects of agricultural legacies could help land managers enhance desired vegetation or restoration outcomes on former agricultural lands.

The native North American fruit, large cranberry (Vaccinium macrocarpon Aiton), is the most valuable agricultural food crop in Massachusetts. Cultivated cranberry is a perennial native Ericaceous shrub that requires sandy soils, low soil pH, and relatively low rates of nitrogen (N) fertilization compared with other crops (CCCCGA 2021). Beginning in the late 1800s, growers developed commercial cranberry farms largely on former peat wetlands located near streams and ponds. Farmers use these water supplies to flood individually-diked, cultivated beds (regionally called “bogs”) as part of the typical annual crop management cycle (Thomas 1990). Although the vegetation from which most individual commercial beds were created is not known precisely, former wetlands likely were a combination of red maple (Acer rubrum) (Golet et al. 1993) and Atlantic white cedar (Chamaecyparis thyoides) swamps (Laderman 1989) with irregular layers of underlying peat. Creation of commercial farm beds from wetlands typically involved leveling, establishing perimeter and interior drainage ditches, installing structures to manage water flow, retaining underlying peat to impede drainage, and applying 2–5 cm of sand every 2–5 years to reduce pests and encourage growth of new fruit-bearing vines (Sandler 2010).

The total area of cranberry cultivation in Massachusetts has remained relatively stable at about 5000–6000 ha since 1960 and the total production rate of about 2 million barrels/yr has changed little since 1980 (USDA 2020). During the same time, the cultivated area of cranberries in Wisconsin (the other main U.S. cranberry-growing region) has increased from 2000 to more than 8000 ha, and production has increased from 700,000 to more than 5 million barrels/yr. A recent report on the Massachusetts cranberry industry concluded that its future will be enhanced by intensifying some of the currently-cultivated area by renovating existing beds with better water control and planting high-yielding cranberry cultivars while simultaneously retiring less profitable or more environmentally-sensitive areas (MA DAR 2016). The report encouraged development of “green exit strategies” to provide farmers with mechanisms to retire portions of existing croplands. A recent analysis concluded that about 30% of the cultivated areas of cranberry farms have been modernized; 20% are prime candidates for retirement because they are environmentally sensitive, hard to manage, or unlikely to modernize; and approximately 50% are candidates for either modernization or retirement (Hoekstra et al. 2020).

Because cranberry farms originated as natural wetlands and occur in low-lying areas near streams and ponds, future retirements are potentially important opportunities to restore the approximately 20% of wetlands in Southeastern Massachusetts that formerly were converted to cranberry farms (Tiner and Zinni 1988). Restored wetlands can provide wildlife habitats, opportunities for recreation and other ecosystem services including carbon (C) storage in vegetation and soils, and improved water quality (Mitsch et al. 2015). However, it is not clear that passive revegetation alone will result in recolonization by wetland vegetation and produce desired ecosystem functions. Observations of recently-retired farms suggest that drainage ditches and years of sanding create conditions that favor plant species such as pitch pine (Pinus rigida) that are widespread in surrounding well-drained uplands (Noyce 2007). Previous studies also indicate that soil organic matter stocks and indicators of biogeochemical cycling in intentionally restored wetlands on former cranberry farms more closely resemble conditions in active farm beds than those in comparable natural wetlands even after many years (Ballantine et al. 2017). Although vegetation composition in retired cranberry farms in New Jersey indicated that non-native species are not large components of post-retirement plant communities (Klee et al. 2019), there are also concerns that retired farms could become locations for colonization and spread of non-native or invasive species.

Understanding the trajectories of plant communities in retired cranberry farms that are left to revegetate with little or no management intervention is important because farm retirements currently outpace the availability of personnel and funding for active restoration projects. Recently developed restoration strategies aim to lessen the effects of agricultural legacies by filling farm bed ditches to restore wetland hydrology, removing sand layers to expose underlying peat, and relying on buried seed banks to restore native wetland plants (Living Observatory 2020). Understanding how plant communities are likely to develop in the absence of active restoration strategies can help stakeholders prioritize where investments in restoration will provide the greatest benefits.

The objective of this study was to quantify plant communities in a chronosequence of active and retired cranberry farm beds to determine vegetation trajectories after farm retirement and to document the extent wetland vegetation recolonization. Farm beds ranged in age from actively farmed to retired for 90 years. We quantified the presence and cover of each plant species; measured tree stem density, canopy cover and stem diameters; and determined soil texture, bulk density, and total C and N content. Plant species were classified as native or non-native and assigned life form and plant wetland indicator designations to evaluate both broad patterns of plant community structure and species-specific patterns over time.

Methods

Study sites

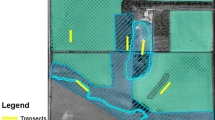

We identified four cranberry farms in active production and 13 former cranberry farms that had been retired for 3–90 years at the time of sampling. All farms were chosen based on Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection spatial data of active cranberry farms and the 2018 Massachusetts Department of Ecological Restoration GIS data layer on retired cranberry farms. Because some farms contained multiple distinct farm beds that were retired in different years, sampling was conducted in 23 beds across the 17 active and retired cranberry farms. We treated each bed as a replicate for our analysis. All sites were adjacent to forested land. All were located in Plymouth, Barnstable, Bristol, or Nantucket County in Southeastern Massachusetts (Fig. 1; Table S1).

The retired beds had similar initial soil and hydrological conditions because of the narrow range of soil conditions caused by cranberry farm management. Sand added every 2–3 years creates a very uniform surface soil profile, pH is maintained between 4.0 and 5.5, and fertilizer additions fall within a very narrow range of values for both N and phosphorus (Ghantous et al. 2023). Because cranberries require well-drained soils, the water table is also tightly controlled by dikes and water control structures to lie deeper than 25 cm but not deeper than 60 cm below the soil surface (Celicourt et al. 2020). When possible, the last year of commercial production was determined from farm managers. The year of retirement was defined as the first year without crop production. For older retired farms for which information from owners was not available, we estimated the retirement age based on town records or aerial images. Farm beds were assigned to one of five age classes: age class 0 (Active), age class 1 (1–9 years retired), age class 2 (10–20 years retired), age class 3 (21–49 years retired), and age class 4 (50 or more years retired) (Fig. S1).

Vegetation sampling

We sampled 21 farm beds from June–September of 2019 with the exception of the Lower Bog bed of the Coonamessett River that was sampled in 2017 and the Windswept Bog that was sampled in 2020. Ten random coordinates within the bounds of the bed were pre-selected in ArcGIS and served as the southeast corners of 3 × 3 m sampling plots. Upon locating the predetermined coordinates in the field with a hand-held GPS, each plot was delineated with a PVC frame.

In each plot, we identified all species present and assigned each a numerical value corresponding to the estimated percent cover of each species present: R = Rare (one small individual), 1 = < 1% cover, 2 = 1–2% cover, 3 = 3–5% cover, 4 = 6–15% cover, 5 = 16–25% cover, 6 = 26–50% cover, 7 = 51–75% cover, 8 = 76–100% cover (Braun-Blanquet et al. 1932; Walker et al. 2018). Cover values were converted to cover class midpoints for further analysis (Daubenmire 1959). This method was identical and comparable to that used to assess other low-stature, species-rich vegetation in the same region (Motzkin et al. 2002; Lezberg et al. 2006; Wheeler et al. 2015). Percent cover categories were assigned for bare ground, standing water, leaf litter, and woody debris. Mosses were not identified to species but assigned one value for the total moss cover per plot. Plants that could not be identified in the field were photographed or collected, and then compared with specimens in the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution/Marine Biological Laboratory herbarium to identify samples to the finest possible taxonomic level following Haines (2011).

To assess trends in community structure and function, we designated each species native or non-native (based on Cullina et al. 2011) and life form (graminoid, forb, vine, shrub, tree) based on the USDA, NRCS PLANTS Database (NRCS 2021). Although we did not measure hydrological conditions directly, we assessed the extent to which vegetation consisted of wetland-associated or non-wetland-associated plants by designating plant wetland indicator status (OBL, FACW, FAC, FACU, UPL) based on the U. S. Army Corps of Engineers (2018) National Wetland Plant List (v3.4). To broadly characterize species as wetland-associated or non-wetland-associated we combined OBL and FACW species into “Wetland” species and FACU and UPL species into “Upland” species. For all plant classifications, when possible, species missing functional designations were assigned categories based on its habitat and the characteristics of species in the same genus. Species that were identified to genus were included in species richness counts only when they unambiguously represented a unique species in the plot.

Percent canopy cover, tree stem density, and tree basal area were quantified in each plot. Percent canopy cover was measured with a spherical crown densitometer (Forestry Suppliers Convex Model A) at the plot center and at each plot corner. Stem density and basal area were determined by counting and measuring diameter at breast height (DBH) of all stems ≥ 2 cm DBH within a 4 m radius of the plot center.

Soil sampling

Soil cores were collected at each plot to characterize soil composition, moisture, and bulk density. Soils from the Lower bed of the Coonamessett River were collected in 2017, soils for Farley Bog and Windswept Bog in 2020, and all other beds in 2018 (one year before we conducted vegetation and tree surveys). One 5-cm diameter soil core to 30 cm was collected in each plot and separated in the field into 0–5 cm, 5–10 cm, and 10–30 cm depths. Gravimetric moisture was determined by oven drying after removing litter and aboveground vegetation. Bulk density was determined from the mass of dry soil within the core volumes. Soil percent carbon (C) and N at each depth were determined by grinding and combusting soil subsamples on a Vario MAX cube analyzer (Ronkonkoma NY). Because soil volumes changed as soil organic matter accumulated in surface soils in retired farms, we estimated changes in soil C and N stocks by calculating the additional soil depth required to obtain an equivalent soil mass compared with the mean soil mass to 30 cm in active farms using the method that Davidson and Ackerman (1993) developed for assessing changes to soil stocks along chronosequences.

Data analysis

Trends in plant vegetation for each age class were evaluated using each farm bed as a replicate. We determined the total number of unique species across the ten plots in each farm bed and calculated the mean and standard error of species per bed for each age class. The mean and standard error of the number of species per bed were calculated for each plant category (native/non-native, life form, and wetland indicator). Species percent cover was used to characterize species abundance and the percent cover of each species in a plot was quantified as the midpoint of the cover category range (Wheeler et al. 2015). The midpoint values were used to calculate the mean percent cover of V. macrocarpon and each native/non-native, life form, and wetland category for each bed. We did not normalize percent cover values by the total plot cover. Percent cover values therefore represent the percent of the plot area covered by each vegetation category (because vegetation canopies consist of multiple layers, the total percent cover in a plot can be greater than 100%). The mean and standard error of percent cover were determined for each species category within each age class. For both species richness and cover analyses based on wetland status, we grouped and categorized species with wetland designations of OBL and FACW as “wetland species” and categorized species with designations of FACU and UPL as “upland species.”

The mean percent tree canopy cover for each farm bed was determined from the cover of each plot. For tree basal area and C stock, we used the sum of all trees in each bed to calculate the mean and standard error for each age class. The mean and standard error of soil C, N, density, and moisture at each depth interval were determined for each age class. The biomass of each tree was calculated from DBH using a standard set of species-specific allometric equations (Jenkins et al. 2004) and tree biomass was summed for each plot. Tree and soil carbon accumulation per year were determined by dividing the total change by bed retirement age in years. Tree biomass was assumed to be 50% C. All data were analyzed in R version 4.0.3.

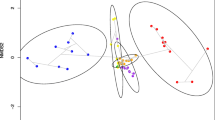

We conducted non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) ordination to visualize trends in the bed species composition of each age class (Kruskal 1964). For the analysis, all the plots in each bed of each age class were combined to construct a Bray–Curtis dissimilarity matrix for the percent cover of each species (Oksannen et al. 2020). We used the metaMDS function in the vegan package in R (R Core team 2020) with 100 randomized runs and three final axis iterations to determine a solution with a stress value < 0.2. Two axes were used to show shifts in species composition between beds and age classes. NMDS ordination was used to visualize the plot-level cover of twelve notable species. The percent cover of each species in each plot was included in the Bray–Curtis dissimilarity matrix. We used the same metaMDS method as in the bed-level analysis. Abundant and focal species were highlighted to provide examples of the change in species presence over time.

Results

Plant community

Total species richness per bed increased from a low of 13 ± 3 (mean ± standard error) in active farm beds to 51 ± 5 in 10–20 year-old beds and then declined to 30 ± 6 in 50 + year-old beds (Fig. 2A). Native species richness followed the same trend because native species comprised the large majority of total species. Non-native species richness per farm bed remained low across all age classes (Fig. 2A). Forb and graminoid species richness showed the same pattern of a peak in the 10–20 year-old age class (Fig. 2B). Shrub species richness was consistently greater than tree and vine species richness, and shrub, tree and vine richness increased steadily with retirement age (Fig. 2B). The mean richness of wetland species (OBL, FACW) increased, peaked in the 10–20 and 21–49 year-old age classes, then declined (Fig. 2C). Facultative and upland species richness followed the same trend but declined somewhat less in older age classes (Fig. 2C).

Plant species richness for total native and non-native species (A), life form groups (B), and plant wetland indicator classes (C) across a chronosequence of active and retired farm beds. For wetland indicator classes, OBL and FACW were combined into “wetland” species, and UPL and FACU were combined into “upland” species. Error bars represent ± standard error of the mean

Vegetation cover in active beds was composed largely of V. macrocarpon (82 ± 6%) but that decreased sharply following retirement and continued to decrease to near zero in 50 + year-old beds (Fig. 3A). Cover of native species (but not including V. macrocarpon) increased from 7 ± 5% in active beds to 80 ± 16% in 1–9 year-old beds and then to 106 ± 8% in 50 + year-old beds (Fig. 3A). Non-native cover remained low across all age classes (Fig. 3A). Forb and graminoid cover increased from near zero in active beds (where they are actively controlled by farmers) to 18–30% in 1–9 and 10–20 year-old beds, then declined slightly in older aged beds (Fig. 3B). Moss cover increased from 4 ± 3% in active beds to 12 ± 4% in 10–20 year-old beds and then remained fairly constant. Vine cover increased from 4 ± 3% in active beds to 38 ± 15% in 10–20 year-old beds and decreased (Fig. 3C). Tree and shrub cover both increased continuously following bed retirement. Shrub cover (56 ± 6%) and tree cover (33 ± 9%) were highest in 50 + year-old beds (Fig. 3C). Wetland species cover increased rapidly in 1–9 year-old beds and then remained fairly constant through 50 + year-old beds (Fig. 3D). Facultative species cover increased continuously following retirement and dominated cover (67 ± 6%) in 50 + year-old beds. Upland species cover increased, was highest in 10–20 year-old beds and then decreased (Fig. 3D).

Cover of cranberries, native and non-native species (A), plant life form groups (B, C), and plant wetland indicator class (D) across a chronosequence of active and retired farm beds. For wetland indicator classes, OBL and FACW were combined into “wetland” species, and UPL and FACU were combined into “upland” species. Error bars represent ± standard error of the mean

Tree canopy cover and tree basal area increased steadily following retirement (Fig. 4A). Red maple (Acer rubrum) and pitch pine (Pinus rigida) accounted for the majority of the increase in basal area. Black gum (Nyssa sylvatica), white pine (Pinus strobus), and gray willow (Salix cinerea) increased in mean basal area over time but contributed less to total basal area (Fig. 4B).

Species composition in active farm beds differed widely from retired beds of all ages (Fig. 5). Although composition overlapped among age classes, species shifted progressively over time (Fig. 5). Each age class had different species that were most frequent and abundant (Fig. 6; Table S2). In active beds V. macrocarpon overwhelmingly dominated and cover of other species was low. In 1–9 year-old beds, V. macrocarpon remained abundant but the herbaceous perennials poison ivy (Toxicodendron radicans), switchgrass (Panicum virgatum), northern dewberry (Rubus flagellaris), bristly dewberry (Rubus hispidus), wool-grass (Scirpus cyperinus), sedges (Carex spp.) and slender-leaved flat-topped goldenrod (Euthamia caroliniana) increased in cover. In 10–20 year-old beds, V. macrocarpon remained the species with the highest cover, T. radicans increased, and R. hispidus and R. flagellaris were still present. S. cyperinus decreased but little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium), P. rigida, A. rubrum and moss cover increased. In 21–49 year-old beds, A. rubrum became the species with the greatest cover, sweet pepperbush (Clethra alnifolia) increased, and some species widespread in wetlands, like swamp loosestrife (Decodon verticillatus) and high-bush blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum), increased. Toxicodendron radicans, P. rigida and R. hispidus declined and R. flagellaris and E. caroliniana became much less abundant (Table S2). In the oldest 50 + year-old beds, cover of C. alnifolia, A. rubrum and V. corymbosum increased and cover of T. radicans and P. rigida declined. Cover of the native shrubs swamp azalea (Rhododendron viscosum), leatherleaf (Chamaedaphne calyculata), and winterberry (Ilex verticillata) and the native trees white pine (Pinus strobus), black tupelo (Nyssa sylvatica) and oaks (Quercus spp.) increased.

Non-metric multidimensional scaling analysis of vegetation of common components of retired farm bed vegetation that changed across a chronosequence of active and retired farm beds. Age classes were: 0—active farms, 1—retired 1–9 years, 2—retired 10–20 years, 3—retired 21–49 years, 4—retired 50 + years

Soil moisture and soil and vegetation carbon

Soil moisture was highest at 0–5 cm and was highest in the oldest 50 + age class (Fig. S2). Soil bulk density was lowest at 0–5 cm and higher but similar at 5–10 and 10–30 cm (Fig. S2). Bulk density remained relatively constant from 1–9 to 21–49 year-old beds but decreased in 50 + year-old beds (Fig. S2).

Shallow soil %C (Fig. 7A) and %N (Fig. 7B) at 0–5 cm increased only slightly between 10–20 and 21–49 year-old beds but then increased more substantially in 50 + year-old beds. Changes to C and N concentrations decreased with soil depth. Soil C stock varied slightly among age classes but increased from 3.8 ± 1.1 kg/m2 in active beds to 16.3 ± 2.6 kg/m2 in 50 + year-old beds (Fig. 7C). Mean aboveground C stock in trees increased from 0 kg/m2 in active and 1–9 year-old beds to 4.3 kg/m2 in 50 + year-old beds (Fig. 7D). The pattern of soil N stock was much like that of C stock with the largest increase occurring between the 21–49 and 50 + age classes (Fig. 7C).

Discussion

Plant community

The trajectories of plant communities in retired cranberry farms followed a consistent pattern over time. The abundance of cultivated V. macrocarpon declined quickly after retirement but cranberries remained present even in 21–49 year-old former beds. Large numbers of native graminoids and forb species rapidly colonized retired beds in the first two decades following retirement but graminoid and forb richness and cover declined in beds retired for more than 20 years. Though tree and shrub richness and cover were lower than that of graminoids and forbs, tree and shrub richness and cover increased slowly over time. Increases in tree canopy cover that occurred 20 or more years after retirement coincided with the onset of decline in graminoid and forb richness and cover. Ultimately vegetation of farm beds retired for five or more decades consisted of nearly closed-canopy forests with abundant A. rubrum and P. rigida and a variety of understory shrubs that occur in wetlands but that are not restricted to wetlands, including C. alnifolia, V. corymbosum and R. viscosum. This trajectory, and especially the predominance of A. rubrum and C. alnifolia in older beds, was very similar to that observed in a chronosequence of five 3–80 year-old retired cranberry farms from New Jersey (Klee et al. 2019).

Following farm retirement, the initial increase in species richness and cover of herbaceous perennials, subsequent gradual decline in herbaceous species, and increase in tree and shrub species richness and cover after several decades, closely resembled the patterns reported in studies of secondary succession after abandonment of croplands in the eastern and central U.S. (Bard 1952; Bazzaz 1968; Pickett 1982; Cramer et al. 2008). The presence of the most common trees and shrubs in the youngest retired beds indicated rapid post-retirement recruitment of both herbaceous and woody species and then subsequent growth of woody species rather than the later recruitment of woody species. This was similar to patterns in many old fields (Bard 1952; Buell et al. 1971; Pickett 1982).

Plant species richness over time in retired cranberry farms began to decline after two decades. This decline contrasted with the pattern in many old fields in which total plant species richness remains high for decades, even after the establishment of dense tree cover and shift of plant species richness from herbaceous to woody species (Pickett 1982; Monk 1983). Both the high diversity of native plant species that occur in open grass and shrublands on sandy soils in the Massachusetts cranberry-growing region (Dunwiddie et al. 1996) and the low tree species richness in the region’s upland forests (Motzkin et al. 2002) may contribute to this sequential rise and fall of plant species richness over time in retired cranberry farm beds. Several other features of the vegetation trajectories in retired farms also differed from those in old fields. First, the flush of recruitment of herbaceous annuals or biennials such as ragweed (Ambrosia artemisiifolia), queen-Anne’s lace (Daucus carota), northern evening primrose (Oenothera parviflora), or sheep sorrell (Rumex acetosella) that is typical very early in old-field succession, did not occur. Instead, almost all the herbaceous species that recruited early following farm bed retirement were perennial species that then remained present for many years. Thick existing year-round cover of V. macrocarpon, high litter cover, and absence of exposed bare soil likely contributed to the very low presence of these typical, short-lived, early-successional species. The low pH of soils and dense plant cover in cultivated cranberry farm soil also potentially discouraged these species from colonizing beds and contributing to the soil seed banks that typically drive early plant recruitment in old fields (Marks and Mohler 1985).

These same conditions also likely contributed to the overwhelming predominance of native species in the post-cropland floras of cranberry farm beds compared with the diverse assemblage and high abundance of non-native species that typically occur quickly in the first 1–2 years in on formerly cultivated old fields (Bazzaz 1968; Pickett 1982; Gill and Marks 1991). While the number of non-native species in old fields declines over time (Pickett 1982), in retired cranberry farms this collection of weedy and widespread non-native and native early-colonizing species did not occur. Low soil pH that closely resembles conditions in native soils may also contribute to the high relative proportion of native species that recruit in retired cranberry farms. Neill et al. (2007) and Von Holle and Motzkin (2007) showed that forests in southeastern Massachusetts that had a legacy of higher pH from applications as long as 50 years ago many more non-native plant species than formerly cleared sites with unaltered native soil pH.

The recruitment of many native plant species into retired cranberry farms likely derives from germination of seeds in buried soil seed banks. These seed banks may be particularly important for wetland-obligate or wetland-associated species such as S. cyperinus, L. terrestris, and D. verticillatus that became important components of the post-retirement flora. Many wetland plants have long-lived seeds that remain buried in soils for many decades before germinating following drawdown or disturbance (van der Valk and Davis 1978; Welling et al. 1988). Pond shores in the Massachusetts cranberry growing region also have rich buried seed banks (Neill et al. 2009). Ditches in active cranberry farm beds may also be locations that allow native wetland plants to persist, and many plants regarded as weeds by commercial cranberry growers are native wetland plants (Sandler et al. 2015). However, the presence and composition of seed banks in former cranberry farms and the role of seed banks in shaping vegetation of retired cranberry farms remains largely unknown.

The colonization by woody plants after bed retirement followed a general pattern of early recruitment but relatively slow expansion of the trees P. rigida and A. rubrum, then a subsequent decline of P. rigida relative to A. rubrum, and an increase in shrubs, particularly C. alnifolia. Both P. rigida and A. rubrum are abundant components of regional forests (Motzkin et al. 2002) and C. alnifolia is abundant along pond shores and wetland edges (Laderman 1989). Pinus rigida seeds germinate predominantly on exposed, sandy mineral soils (Bramble and Goddard 1942; Ledig and Little 1979) that typically occur following fires (Jordan et al. 2003) or abandonment of land from cultivation (Motzkin et al. 1996). Although soil exposure is low on newly-retired beds primarily because of high remaining V. macrocarpon cover, soil conditions favor P. rigida germination likely because of the high soil sand content created by regular sand applications during cranberry cropping. Because P. rigida occurs predominantly on well-drained soils, a slowing of the rate of increase in P. rigida basal area about 20 years after retirement is potentially associated with concurrent increases in soil moisture (Fig. S2). In contrast with P. rigida, A. rubrum is widespread on moist soils and can comprise more than 90% of tree cover in forested swamps (Golet et al. 1993). A. rubrum germinates readily in old fields (Rankin and Pickett 1989), but unlike P. rigida, it also germinates in forest understories (Golet et al. 1993). Native shrubs, including C. alnifolia, V. corymbosum and C. calyculata, were an important component of the flora of older retired beds. Moss facilitates germination of all of these species (Cullina 2002), so the increase of these species over time may be related to coincident gradual increase of moss cover. The presence of moss also increases the success of seedling establishment of white pine (Pinus strobus) (Smith 1951), an upland tree that was a lesser component of basal area but also increased with time since retirement.

Although P. rigida, A. rubrum, and P. strobus are typically found in upland forests adjacent to former cranberry farms, the woody vegetation that developed over time on retired cranberry farm beds differed substantially from regional, well-drained, upland forests by the conspicuously low presence of oak species (black oak, Quercus velutina; white oak, Q. alba; scarlet oak, Q. coccinea) that dominate regional tree cover (Motzkin et al. 2002; Eberhardt et al. 2002). Nor did the post-retirement vegetation resemble C. thyoides swamps, and we did not record C. thyoides at any site. The woody vegetation more than five decades post-retirement typically consisted of a relatively atypical mixture of P. rigida, A. rubrum and facultative or wetland-associated shrubs.

Although non-native species comprised less than 11% of species richness and less than 3% of plant cover across all active and retired bed ages, two species of non-native woody plants, gray willow (Salix cinerea) and glossy false buckthorn (Frangula alnus) may be of particular management concern because of their recent and rapid expansion. S. cinerea is a European willow that has become widely naturalized in wetlands including retired cranberry farms in eastern New England and may replace native willows (Zinovjev and Kadis 2008). Frangula alnus is a shrub native to Eurasia and North Africa that has spread into forest understories and wetlands in northeastern North America (Kearlsey 1999; Frappier et al. 2003; McDonald et al. 2008). Control of both species is difficult, S. cinerea because of its extensive roots and clonal habit (Griffiths et al. 2018; LHPRISM 2021) and F. alnus because its fruits are widely consumed and spread by birds (Catling and Porebski 1994).

Soil and vegetation C stocks

Soil percent C and N and soil C and N stocks increased substantially only in the oldest 50 + year-old farm beds. This increase coincided with the large increase in the tree canopy that occurred between 21–49 year and 50 + year-old beds and likely reflected an increase in the depth of the soil O (organic) horizon that typically accumulates under upland forests of the region (Neill et al. 2007). Increases in C and N stocks were smaller than increases in soil percent C and N because there was a concurrent decrease in soil bulk density (and hence surface soil mass) in C- and N-rich surface soil layers. Soil percent C was similar to that in other active and actively restored former cranberry farms (Bartolucci et al. 2021) and the changes to soil percent C and N in 21–49 year-old retired beds were generally similar to the changes observed in 30–35 year-old and 50–55 year-old restored wetlands in New York (Ballantine et al. 2017).

Rates of soil C accumulation for retired cranberry farms of about 0.057 kg C/m2/yr were somewhat higher than the broad global average of soil accumulation rates for forests (0.034 kg C/m2/yr) or grasslands (0.033 kg C/m2/yr) on former agricultural lands (Post and Kwon 2000). They were also higher than the 0.020 kg C/m2/yr reported from 100-year-old aggrading mixed hardwood and eastern hemlock forests in central Massachusetts (Finzi et al. 2020) or the 0.01–0.02 kg C/m2/yr reported for Canadian forested peatlands (Beaulne et al. 2021). The increases of soil C stocks of roughly 70% after 70 years were much higher than the 6–9% increases reported for similar time spans in a review of soil C change on forest aggrading on former agricultural land (Nave et al. 2013). At the same time, the rates of soil C accumulation we measured were lower than a broad average of 0.118 g C/m2/yr calculated for natural wetlands (Mitsch et al. 2013) but not atypical of the long time required to reestablish original rates of C sequestration in restored wetlands (Burden et al. 2019). Soil C accumulation rates intermediate between those in aggrading upland forests and natural wetlands were consistent with the vegetation composition of retired cranberry farms, which was intermediate between upland forest and forested wetlands.

The rate of annual C accumulation in tree aboveground biomass that we measured of 0.06 kg C/m2/yr was lower than rates for central Massachusetts hardwood forests of 0.28 kg C/m2/yr measured by forest inventories (Eisen and Plotkin 2015), 0.200 kg C/m2/yr for hardwood forest or 0.166 kg C/m2/yr for hemlock forest measured by eddy flux (Finzi et al. 2020). Our rates were more similar to the C accumulation rates of 0.053 kg C/m2/yr and 0.089 kg C/m2/yr measured in New Hampshire and Pennsylvania hardwood forests (Hoover 2011). The coarse texture and low fertility of soils throughout the Massachusetts cranberry growing region (Upham 1969), regular sand applications to active farms, and soil conditions wetter than typical upland forests, likely contributed to lower rates of annual aboveground C accumulation.

Soil moisture in retired farm beds was highest in the oldest 50 + age class. Although these values represented only one-time measurements during summer field visits, based on the well-drained condition of actively-farmed beds, they suggested that surface soils likely became wetter over time. This pattern was consistent with increases in mosses and wetland-associated vascular plants over time. This trend also was consistent with our observations of the slumping, deterioration and filling with organic material of the former bed drainage ditches in older retired farm beds. Deterioration and filling of ditches with organic matter likely has the effect of reducing bed drainage and raising local water tables (Fisher et al. 1996; LaRose et al. 1997; Landry and Rochefort 2012) because groundwater inputs are typical of both active and retired cranberry farms (Hare et al. 2017; Neill et al. 2018; Living Observatory 2020). Increasing wetness suggests that while we found that vegetation in our oldest retired beds resembled upland forest, longer-term vegetation trajectories could favor more species typical of wetter forests over time. Because increasing soil inundation likely is associated with both slower tree growth and greater total accumulation of soil organic matter (including facilitation by moss cover), increasing soil moisture over time may increase the relative proportion of C stored in soils versus aboveground tree biomass, such as occurs in natural forested peatlands (Beaulne et al. 2021). It is likely that soil moisture in retired beds will be influenced by local topography, and ground and surface water configurations that we did not study in detail.

Implications for wetland restoration management

Our findings have several potential implications for the management of the cranberry farms that are likely to be retired in the future. We found that legacies of cranberry cultivation, including sand deposition and the presence of drainage ditches promoted passive revegetation trajectories that resulted in young forests dominated by tree species characteristic of surrounding upland forests. Although many species of wetland obligate plants colonize retired cranberry farm beds, many of these species disappear in older retired beds, the cover of the remaining wetland obligate species decreases, and wetland species are replaced by more widespread facultative plant species. Although the vegetation that results 50 + years after cranberry farm retirement retains some wetland obligate plants and some wetland characteristics, the flora is strongly dominated by common and widespread non-wetland species.

Economic pressures on Massachusetts cranberry growers and the potential for wetland restoration has created interest in developing new methods that have the aim of restoring wetland hydrology and wetland-obligate vegetation to retired cranberry farmland. These active restoration methods include removing dikes and water control structures, filling former farm ditches to raise groundwater levels, removing sand to lower former farm bed elevations, and breaking up the remaining cranberry vegetation to create bare soil and soil microtopography. Preliminary evaluations indicate that these methods result in higher water table elevations, moister soils, and rapid colonization of former farm beds by a diverse array of predominantly native herbaceous plant species (Living Observatory 2020). While the equivalent long-term trajectories of plant communities following more active restoration have not yet been evaluated, our results indicate that such interventions will be necessary to promote and sustain the development of future plant communities with larger proportions of wetland species on former cranberry farms.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed for this study are currently available from the corresponding author on request. Datasets associated with an accepted version of this manuscript will be permanently deposited in the Woods Hole Oceanographic/Marine Biological Laboratory data repository.

References

Ballantine KA, Anderson DR, Pierce EA, Groffman PM (2017) Restoration of denitrification in agricultural wetlands. Ecol Engin 106:570–577

Bard GE (1952) Secondary succession on the Piedmont of New Jersey. Ecol Monogr 22:195–215

Bartolucci NN, Anderson TR, Ballantine KR (2021) Restoration of retired agriculture land to wetland mitigates greenhouse gas emissions. Rest Ecol 29:e13314

Bazzaz FA (1968) Succession on abandoned fields in the Shawnee Hills, southern Illinois. Ecol 49:924–936

Beaulne J, Marneau M, Magnan G, Boucher É (2021) Peat deposits store more carbon than trees in forested peatlands of the boreal biome. Sci Rep 11:2657

Bellemere J, Motzkin G, Foster DR (2002) Legacies of the agricultural past in the forested present: an assessment of historical land-use effects on rich mesic forests. J Biogeogr 29:1401–1420

Bramble WC, Goddard MK (1942) Effect of animal coaction and seedbed condition on regeneration of pitch pine in the Barrens of central Pennsylvania. Ecol 23:330–335

Braun-Blanquet J, Fuller GD, Conrad HS (1932) Plant sociology: the study of plant communities (English translation). McGraw Hill, NY

Brown CD, Boutin C (2009) Linking past land use, recent disturbance, and dispersal mechanism to forest composition. Biol Cons 14:1647–1656

Buell MF, Buell HF, Small JA (1971) Invasion of trees in secondary succession on the New Jersey Piedmont. Bull Torrey Bot Club 98:67–74

Burden A, Barbutt A, Evans CD (2019) Effect of restoration on saltmarsh carbon accumulation in Eastern England. Biol Lett 15:20180773

Catling P, Porebski ZI (1994) The history of invasion and current status of glossy buckthorn, Rhamnus frangula, in southern Ontario. Can Field Nat 108:305–310

CCCCGA (Cape Cod Cranberry Growers Association) (2021) How cranberries grow. https://www.cranberries.org/how-cranberries-grow#:~:text=These%20factors%20include%20acid%20peat,originally%20created%20by%20glacial%20deposits

Celicourt P, Gumiere SJ, Lafond JA, Gumiere T, Gallichand J, Rousseau AN (2020) Automated mapping of water table for cranberry subirrigation management: comparison of three spatial interpolation methods. Water 12:3322. https://doi.org/10.3390/w12123322

Chazdon RL, Lindenmayer D, Guarigusta RR, Crouzeilles R, Benayas RMR, Chavero LL (2000) Fostering natural forest regeneration on former agricultural land through economic and policy interventions. Env Res Lett 15:043002

Cramer VA, Hobbs RJ, Standish RJ (2008) What’s new about old fields? Land abandonment and ecosystem assembly. Trends Ecol Evol 23:104–112

Cullina MD, Connolly, Sorrie B, Somers P (2011) The vascular plants of Massachusetts: a county checklist. Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife, Westborough

Cullina W (2002) Native trees, shrubs and vines: a guide to using, Growing and propagating North American woody plants. Houghton Mifflin

Daubenmire RF (1959) Canopy coverage method of vegetation analysis. Northwest Sci 33:43–64

Davidson EA, Ackerman IL (1993) Changes in soil carbon inventories following cultivation of previously untilled soils. Biogeochem 20:161–193

Dunwiddie PW, Zaremba RE, Harper KA (1996) A classification of coastal heathlands and sandplain grasslands in Massachusetts. Rhodora 98:117–145

Dupouey JL, Dambrine E, Laffite JD, Moraes C (2002) Irreversible impact of past land use on forest soils and biodiversity. Ecol 83:2978–2984

Eberhardt RW, Foster DR, Motzkin G, Hall B (2002) Conservation of changing landscapes: vegetation and land-use history of cape cod national seashore. Ecol Appl 13:68–84

Eisen K, Barker Plotkin A (2015) Forty years of forest measurements support steadily increasing aboveground biomass in a maturing, Quercus-dominant northeastern forest. J Torrey Bot Soc 142:97–112

Finzi AC, Giasson MA, Barker Plotkin AA, Aber JD, Boose ER, Davidson EA, Dietze MC, Ellison AM, Frey SD, Goldman E, Keenan TF, Melillo JM, Munger JW, Nadeloffer KJ, Ollinger SV, Orwig DA, Pdeterson N, Richardson AD, Savage K, Tang J, Thompson JR, Williams GA, Wofsy SC, Zhou Z, Foster DR (2020) Carbon budget of the harvard forest long-term ecological research site: pattern, process, and response to global change. Ecol Monogr 90(4):e01423

Fisher AS, Podniesinski GS, Leopold DJ (1996) Effects of drainage ditches on vegetation patterns in abandoned agricultural peatlands in central New York State. Wetlands 16(4):397–409

Foster DR (1992) Land-use history (1730–1990) and vegetation dynamics in central New England, USA. J Ecol 80:753–772

Foster DR, Swanson F, Aber J, Burke I, Brokaw N, Tilman D, Knapp A (2003) The importance of land-use legacies to ecology and conservation. BioSci 53:77–88

Frappier B, Eckert RT, Lee TD (2003) Potential impacts of the invasive exotic shrub Rhamnus frangula L. (Glossy buckthorn) on forests of southern New Hampshire. Northeast Nat 10:277–296

Ghantous K, Syliva M, Gauvin D (2023) Cranberry chart book 2021–2023. University of Massachusetts Cranberry Station, Wareham, MA. https://ag.umass.edu/cranberry/publications-resources/cranberry-chart-book-archive

Gill DS, Marks PL (1991) Tree and shrub seedling colonization of old fields in Central New York. Ecol Monogr 61:193–205

Golet FC, Calhoun AJK, DeRagon WR, Lowrey DJ, Gold AJ (1993) Ecology of red maple swamps in the glaciated Northeast: a community profile. Biol Rep 12, U.S. Dept Int, US Fish Wild Serv, Wash DC, 151 p

Grau R, Aide TM, Zommerman JK, Thomlinson JR, Helmer E, Zou X (2003) The ecological consequences of socioeconomic and land-use changes in postagriculture Puerto Rico. BioSci 53:1159–1168

Griffiths JH, Armstrong R, Innes R, Terry J (2018) Can aerial herbicide application control Gray Willow (Salix cinerea L) and stimulate native plant recovery? Ecol Manage Restor 19:49–57

Haines A (2011) Flora Nova Angliae: a manual for the identification of native and naturalized higher vascular plants of New England. Yale University Press, New Haven

Hare DK, Boutt DF, Clement WP, Hatch CE, Davenport G, Hackman A (2017) Hydrogeological controls on patterns of groundwater discharge in peatlands. Hydrol Earth Syst Sci 21:6031–6048

Hoekstra B, Kennedy C, Neill C (2020) Trends in the Massachusetts cranberry industry create opportunities for restoration of formerly-cultivated riparian wetlands. Restor Ecol 28:185–195

Hoover CM (2011) Assessing seven decades of carbon accumulation in two U.S. northern hardwood forests. Forests 2:730–740

Huennecke LF, Hamburg SP, Koide R, Mooney HA, Vitousek PM (1990) Effects of soil resources on plant invasion and community structure in Californian serpentine grassland. Ecol 71:478–491

Jenkins JC, Chojnacky DC, Heath LS, Birdsey RA (2004) A Comprehensive database of diameter-based biomass regressions for North American tree species. General Technical Report NE-319. US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Northeastern Research Station. 45 pp

Jordan MJ, Patterson WA III, Windisch AG (2003) Conceptual ecological models for the Long Island pitch pine barrens: implications for managing rare plant communities. For Ecol Manage 185:151–168

Kearlsey JB (1999) Inventory and vegetation classification of floodplain forest communities in Massachusetts. Rhodora 101:105–135

Keenan RJ, Reams GA, Achard F, de Freitas JV, Grainger A, Lindquist R (2015) Dynamics of global forest area: results from the FAO global forest resources assessment 2015. For Ecol Manage 352:9–20

Khuman TR, Pearson SM, Turner MG (2011) Agricultural land-use history increases non-native plant invasion in a southern Appalachian forest a century after abandonment. Can J for Res 41:920–929

Klee R, Zimmerman KI, Daneshgar PP (2019) Community succession after cranberry bog abandonment in the New Jersey Pinelands. Wetlands 39:777–888

Kruskal JB (1964) Multidimensional scaling by optimizing goodness of fit to a nonmetric hypothesis. Psychomet 29:1–27

Kulmatiski A, Beard KH, Stark JM (2006) Soil history as a primary control on plant invasion in abandoned agricultural fields. J Appl Ecol 43:868–876

Laderman A (1989) The ecology of Atlantic white cedar wetlands: a community profile. US Fish Wildl Serv, Biol Rep 85(7.21):114

Landry J, Rochefort L (2012) The drainage of peatlands: impacts and rewetting techniques. Peatland Ecology Research Group, University of Laval, Quebec

LaRose S, Price J, Rochefort L (1997) Rewetting of a cutover peatland: hydrological assessment. Wetlands 17(3):416–423

Ledig FT, Little S (1979) Pitch pine (Pinus rigida Mill.): ecology, physiology and genetics. In: Forman RTT (ed) Pine barrens: ecosystem and landscapes. Academic Press, NY, pp 347–371

Leppa K, Korkiakoski M, Nieminen M, Laiho R, Hotanen J, Kieloaho A, Korpela L, Laurila T, Lohila A, Minkkinen K, Makipaa R, Ojanen P, Pearson M, Penttila T, Tuovinen J, Launiainen S (2020) Vegetation controls of water and energy balance of a drained peatland forest: responses to alternative harvesting practices. Agric for Meteor 295:1–17

Lezberg A, Buresch K, Neill C, Chase T (2006) Mechanical land clearing to promote establishment of coastal sandplain grassland and shrubland communities. Rest Ecol 14:220–232

LHPRISM (Lower Hudson Partnership for Regional Invasive Species Management) (2021) Salix atrocinerea. https://www.lhprism.org/species/salix-atrocinerea#:~:text=As%20with%20any%20other%20invasive,be%20hand%20pulled%20or%20sprayed

Living Observatory (2020) Learning from the restoration of wetlands on cranberry farmland: preliminary benefits assessment. Living Observatory, Plymouth, MA

MA DAR (Massachusetts Department of Agricultural Resources (2016) The Massachusetts cranberry revitalization task force: final report. Massachusetts Department of Agricultural Resources, Boston

Marks PL, Mohler CL (1985) Succession after elimination of buried seed from a recently-plowed field. Bull Torrey Bot Club 112:376–382

McDonald RI, Motzkin G, Foster DR (2008) Assessing the influence of historical factors, contemporary processes and environmental conditions on the distribution of invasive species. J Torrey Bot Soc 135:260–271

Mitsch WJ, Bernal B, Nahlik AM, Mander U, Zhang L, Anderson CJ, Jørgensen SE, Brix H (2013) Wetlands, carbon, and climate change. Land Ecol 28:583–597

Mitsch WJ, Bernal B, Hernandez ME (2015) Ecosystem services of wetlands. Int J Biodiv Sci Eco Serv Manage 121:1–4

Monk CD (1983) Relationship of life forms and diversity in old-field succession. Bull Torrey Bot Club 110:449–453

Motzkin G, Foster DR, Allen A, Harrod J, Boone R (1996) Controlling site to evaluate history: vegetation patterns of a New England sand plain. Ecol Monogr 66:345–365

Motzkin G, Eberhardt R, Hall B, Foster DR, Harrod D, MacDonald D (2002) Variation across cape cod, Massachusetts: environmental and historical determinants. J Biogeogr 29:1439–1454

Nave IE, Swanston CW, Mishra U, Nadelhoffer KJ (2013) Afforestation effects on soil carbon storage in the United States: a synthesis. Soil Sci Soc Am J 77:1035–1047

Neill C, Von Holle B, Kleese K, Ivy KR, Collins AR, Treat C, Dean M (2007) Historical influences on the vegetation and soils of the Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts coastal sandplain: implications for conservation and restoration. Biol Cons 136:17–32

Neill C, Bezerra MO, McHorney R, O’Dea CB (2009) Distribution, species composition and management implications of seed banks in southern New England coastal plain ponds. Biol Cons 142:1350–1361

Neill C, Scott L, Kennedy C, Jakuba J, McHorney R (2018) Nutrient balances in Southeastern Massachusetts cranberry bogs. Final report to the Buzzards Bay National Estuary Project, Massachusetts Office of Coastal Zone Management, April 18

Noyce G (2007) Biogeochemistry and vegetation in a cranberry bog chronosequence. Semester in Environmental Science. Marine Biological Laboratory, Woods Hole

NRCS (Natural Resources Conservation Service) (2021) The plants database national plant data team. United States Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service, Greensboro NC http://plants.usda.gov

Oksanen JF, Blanchet G, Friendly M, Kindt R, Legendre P. McGlinn D, Minchin PR, O’Hara RB, Simpson GL, Solymos P, Stevens MHH, Szoecs E, Wagner H (2020 vegan: community ecology package. R package version 2.5-7. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=vegan

Pickett STA (1982) Population patterns through twenty years of oldfield succession. Vegetatio 59:45–59

Post WM, Kwon KC (2000) Soil carbon sequestration and land use change: processes and potential. Global Change Biol 6:317–327

R Core Team (2020) R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. URL https://www.R-project.org/

Rankin WT, Pickett STA (1989) Time of establishment of red maple (Acer rubrum) in early oldfield succession. J Torrey Bot Club 1216:182–186

Rawinski T (2005) European gray willow (Salix cinerea): a message from Tom Rawinski. US Forest Serv Invasive Plants Newsbriefs 14

Rozendaal DMA et al (2019) Biodiversity recovery of neotropical secondary forests. Sci Adv 5:eaau3114

Sandler H, Dalbec L, Ghantous K (2015) Identification guide for weeds in cranberry bogs. U Mass Cranberry Sta, East Wareham

Sandler H (2010) Best management practices for Massachusetts cranberry production. U Mass Cranberry Sta. East Wareham, MA. https://ag.umass.edu/cranberry/publications-resources/best-management-practices

Smith DM (1951) The influence of seedbed conditions on the regeneration of eastern white Pine. Bulletin 545. Conn Agric Expt Sta, New Haven

Thomas JD (ed) (1990) Cranberry harvest: a history of cranberry growing in Massachusetts. Spinner, New Bedford

Tiner RW, Zinni W (1988) Recent wetlands trends in Southeastern Massachusetts. US Fish Wildl Serv Nat Wetlands Inventory Proj, Newton Corner

Upham CW (1969) Soil survey of Plymouth County Massachusetts. US Dept Agric, Soil Cons Serv. US Gov Printing Office, Washington DC

US Army Corps of Engineers (2018) National wetland plant list, version 3.4. U. S. corps of engineers, engineer research and development center. Cold Region Res Engin Lab, Hanover

USDA (2020) United States Department of Agriculture National Agricultural Statistics Service. https://www.nass.usda.gov/Statistics_by_State/Massachusetts/index.php

van der Valk AG, Davis CB (1978) The role of seed banks in the vegetation dynamics of prairie marshes. Ecol 59:322–335

Von Holle B, Motzkin G (2007) Historical land use and environmental determinants of nonnative plant distribution in coastal southern New England. Biol Cons 136:33–43

Walker DA, Daniëls FA, Matveyeva NV, Šibik J, Walker MD, Breen AL, Druckenmiller LA, Raynods MK, Bültmann H, Hennekens S, Buchhorn M, Epstein HE, Ermokhina K, Fosaa AM, Heidmarsson S, Heim B, Jónsdóttir I, Koroleva N, Lévesque E, MacKenzie WH, Henry GHR, Nilsen L, Peet R, Razzhivin V, Talbot SS, Telyanitkov M, Thannheiser D, Webber PJ, Wirth LM (2018) Circumpolar arctic vegetation classification. Phytocoenologia 48(2):181–201

Welling CH, Rl P, Van der Valk AG (1988) Recruitment from the seed bank and the development of zonation of emergent vegetation during a drawdown in a prairie wetland. J Ecol 76:483–496

Wheeler MC, Neill C, Loucks E, Weiler A, Von Holle B, Pelikan M, Chase T (2015) Vegetation removal and seed addition contribute to coastal sandplain grassland establishment on former agricultural fields. Restor Ecol 23:539–547

Whitney GG (1994) From coastal wilderness to fruited plain: a history of environmental change in temperate North America from 1500 to the present. Cambridge U Press, Cambridge

Zinovjev A, Kadis I (2008) European rusty willow S. atrocineria in eastern Massachusetts. Salicicoloa (http://172.104.19.75/articles/atrocinerea/)

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by grants from the Massachusetts Division of Ecological Restoration’s Cranberry Program, the Northeast Climate Science and Adaptation Science Center at the University of Massachusetts, the Fund for Climate Solutions of the Woodwell Climate Research Center, a summer research fellowship grant to Benjamin Hoekstra from Grinnell College, the Agricultural Research Service of the U.S. Department of Agriculture at the University of Massachusetts Cranberry Station, and the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture Hatch project (CONS 01024). We think Andy Xu, Nathaniel Fay, and Lily Thompson for help with fieldwork. Pamela Polloni, Michael Whittemore, and the late Donald Schall graciously assisted with some plant surveys and plant identification. We thank the following for permission to conduct field sampling: Buzzards Bay Coalition, Jon Chorey, A. D. Colburn, and Gary Anderson of the Falmouth Rod and Gun Club, Gilmore Cranberry Company, Harwich Conservation Trust, A. D. Makepeace Company, Mass Audubon, Mass Wildlife, Nantucket Conservation Foundation, Onset Fire District, Town of Falmouth MA, Town of Mashpee MA, Town of Plymouth MA and the UMass Cranberry Station. We thank Casey Kennedy for helping to coordinate sampling of active cranberry farms and Paul Lefebvre for drafting the site map. An independent project by Genevieve Noyce in the Marine Biological Laboratory’s Semester in Environmental Science Program provided the original inspiration for our chronosequence design. The authors also thank Linda Deegan, Glorianna Davenport and Alex Hackman for insights into the ecological trajectories of retired and restored cranberry farms.

Funding

This project was supported by grants from the Massachusetts Division of Ecological Restoration’s Cranberry Program, the Fund for Climate Solutions of the Woodwell Climate Research Center, a summer research fellowship grant to Benjamin Hoekstra from Grinnell College, the Agricultural Research Service of the U.S. Department of Agriculture at the University of Massachusetts Cranberry Station, and the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture Hatch project (CONS 01024).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CN designed the study. AP and CN analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. HM, BH and AP made the field measurements. SK contributed the multivariate statistical analysis and analysis of community change. All authors read and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethical approval

Not applicable. No animal or human subjects were involved.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Neill, C., Pulak, A.M., Miller, H.J. et al. Trajectories of plant communities in Massachusetts, USA cranberry farms discontinued from agriculture. Wetlands Ecol Manage 31, 697–713 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11273-023-09942-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11273-023-09942-3