Abstract

The increasing health inequity and injustice of the COVID-19 pandemic rendered visible the inadequacy of global health governance, and exposed the self-interested decision-making of states and pharmaceutical companies. This research explores the advocacy activities of humanitarian and development international non-governmental organizations (INGOs) in responding to this inequality and investigates how they framed alternatives for global health justice. It reviews 47 organizational documents and 43 media articles of five INGOs (ActionAid, Médecins Sans Frontières, Oxfam, Save the Children, and World Vision) and points to the importance of understanding advocacy frames in analyzing how these organizations prioritize agendas and advocacy strategies. The dominance of the ‘human rights’ frame, sometimes in combination with ‘scientific evidence’ and ‘security’ frames, reflects the identities, mandates, and histories of campaigning and collaboration of these INGOs. This paper contends that the advocacy of humanitarian and development INGOs highlights both deontological and teleological ethics, promoting the voices of people in lower-income countries, clarifying duty bearers and their accountabilities, and addressing structural barriers from a human rights perspective in a global health agenda setting.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The experience of the COVID-19 pandemic shows that the provision of global public goods remains a pressing and unmet issue across the world, and demonstrates that the current global governance and market systems are failing to meet this challenge (Saksena, 2021). Although public funding enabled the development of vaccines as a global public good (Mantilla & Barona, 2022), the attempt to distribute them through COVAX ended up being dependent on aid mechanisms. This was because of both vaccine nationalism and pharmaceutical company monopolies (Brown, 2021; Peacock, 2022). This major failure of global health governance on this issue emphasizes the significant role of and need for non-governmental organizations (NGOs) to promote alternatives for the public good (Dolšak & Prakash, 2022). During the COVID-19 pandemic, this included advocating for global health justice, as well as delivering health services and influencing national pandemic responses (Capano et al., 2020; Levine et al., 2023).

This paper draws attention to the advocacy activities of international NGOs (INGOs) involved in international development and humanitarian actions during the COVID-19 pandemic. Humanitarian and development INGOs have strengthened their roles as advocates, amplifying the voices of people in lower-income countries (Lindenberg & Bryant, 2001). As transnational actors, they attempted to influence health agendas and generate public support for global health justice at both national and international levels (Shiffman, 2007). However, there is little research that explains why and how INGOs adopt some issues as part of an advocacy agenda and not others (Carpenter, 2007). To redress this gap, this paper draws on framing theory to examine INGOs’ advocacy for global health justice and understand their processes of generating meaning and significance, and looks at how this reflects the identities and key values of these organizations (Van der Veen, 2011).

The research explores how humanitarian and development INGOs have advocated for global health justice in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, by investigating the following research questions:

-

1.

How do international humanitarian and development NGOs frame their COVID-19-related advocacy?

-

2.

How does the frame that INGOs employed shape their advocacy issues and strategies? What added values, if any, are associated with the frame?

-

3.

What are the commonalities and differences between the case INGOs? What factors can account for the identified commonalities and differences?

Background

NGO Global Health Advocacy

Humanitarian and development NGOs have played a significant role in providing health services in many places across the world because of both their access to local communities and cost-efficiency (Yoo, 2022). Yet while the role of NGOs as service providers has been criticized as diminishing the accountability of states to provide functioning health systems (Obeng-Odoom, 2012), their role as advocates for global health equity has been welcomed and continues to grow (Brass et al., 2018). Advocacy activities can shine a spotlight on otherwise unseen issues (Shiffman & Smith, 2007) and encourage health systems to become more favorable for disadvantaged people (Anaf et al., 2020). In particular, the advocacy work of INGOs often highlights global health inequality from a human rights perspective (Meier & Gostin, 2018).

Development INGOs have a long history of advocating for equal access to essential medicines in lower-income countries. One complex factor that has long impeded people’s access to medicines is the intellectual property regime—the Trade Related Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) agreement—which was established by the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 1995. In response, global civil society organizations initiated the ‘Access to Essential Medicine Campaign’ to advocate for the right to access to affordable medical interventions (Nelson, 2021). In response to the campaign, the WTO’s ‘Declaration on the TRIPS Agreement and Public Health’, widely known as the Doha Declaration, affirmed flexibility under the TRIPS agreement to ensure improved access to medicines in lower-income countries (Sell, 2001).

In October 2020, India and South Africa submitted a proposal to the WTO to request a temporary waiver on certain intellectual property regulations in the TRIPS agreement to allow increased access to all COVID-19-related vaccines, technologies, and treatments. This proposal was supported by many lower-income countries, civil society organizations, international organizations, including the World Health Organization (WHO), and supporters of the campaign framed access to these medicines as a human right (Davies, 2022). However, some WTO members, including the UK, Germany, Norway, Switzerland, and the US withheld their support, although the US later changed its position to back the waiver proposal in May 2021. The COVID-19 TRIPS waiver was finally agreed to at the WTO on 17 June 2022, noting immunization as a global public good but also limiting the waiver’s scope to COVID-19 vaccines, and excluding treatments, tests, medical devices, and manufacturing methods (Correa & Syam, 2022).

Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, some development INGOs also raised wider issues beyond the unequal distribution of vaccines. For example, certain European development INGOs called for increased aid, debt cancelation, and the transformation of the neoliberal global system (Szent-Iványi, 2022). Although these issues have been on advocacy agendas over the last decades, the COVID-19 pandemic provided INGOs with the opportunity to reflect on their pre-crisis advocacy activities and shape new priorities (Green, 2020).

The advocacy agendas of INGOs are shaped by their decisions around what issues to prioritize and which networks to work with (Jordan and Van Tuijl, 2000). The choice of advocacy issues to focus on during the pandemic was influenced by INGOs’ existing priorities based on their moral, organizational or reputational incentives (Szent-Iványi, 2022). Membership in advocacy networks is also critical for gaining visibility and legitimacy and amplifying resources and power to influence policies (Alexander et al., 2023; Dolšak & Prakash, 2022; Smith & Shiffman, 2016). This indicates the importance of looking at an INGO’s wider network to understand the context and background of its health advocacy.

Global Health and Framing

Global health issues emerge when a global health problem is defined as an issue by advocates and concerted efforts are mobilized to affect outcomes (Carpenter, 2007). The understanding of what is and isn’t a global health issue is shaped by several influential factors. Shiffman and Smith (2007) identified these factors as the “power of actors, ideas to portray the issue, political contexts and the characteristics of issues” and argued for the importance of analyzing the frame “in which an issue is understood and portrayed publicly” (Ibid. p. 1371).

Framing theory pays attention to the process that creates meanings and strategic choices (Van der Veen, 2011) and shapes priority or neglect (Nunes, 2016). Goffman (1974) defines frames as the “schema of interpretation” (p.45) in which people “locate, perceive, identify and label” social events (p.21).

Global health governance is a battlefield of competing frames. McInnes and Lee (2012) suggest “evidence-based medicine,” “economics,” “human rights,” “security,” and “development” as five frames that are often simultaneously employed to shape and understand global health issues. Drawing on these five frames, Shiffman and Shawar (2022) come up with three categories of framing processes—“securitization,” “moralization” and “technification”. These categories have three respective focuses: threats to security, normative and ethical values, and science and expert knowledge.

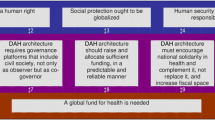

Drawing on these categories, this paper will focus on the role of human rights, scientific evidence and security in global health advocacy. The human rights frame centers around ethical values such as equity and justice; the scientific evidence frame is based on the belief in technical measures to identify and solve health issues; the security frame involves human security and national interests driven by fear of political instability and the loss of life, emphasizing the role of national and international policies in regulating these risks (McInnes & Lee, 2012; Shiffman & Shawar, 2022).

The importance of framing is also noted in social movement literature (Magrath, 2014). Exploring an advocacy organization’s framing can assist in examining their perceptions of and communications about issues (Benford & Snow, 2000). Further, studying framing can shed light on an organizations’ reasons for engagement, including if an issue has been strategically selected to gain legitimacy or increase reputation (McInnes & Lee, 2012) and whether it reflects their core values and identities (Van der Veen, 2011). Framing theory can offer insights into the messages produced and delivered by humanitarian and development INGOs during the pandemic.

Methodology

A qualitative study was conducted to analyze how humanitarian and development INGOs have advocated for global health justice in the wake of COVID-19. For this purpose, communications materials of five major INGOs were selected for analysis.

Oxfam, ActionAid, Save the Children and World Vision were chosen as representing influential INGOs in the development sector. Among these, Oxfam, ActionAid and Save the Children are committed to advocacy in the framework of a human rights-based approach, but each has a different strategic focus: respectively, they are either campaign-driven, grassroots-led or a legalist approach (Plipat, 2005). World Vision is the largest NGO of the group and has a significant role in humanitarian aid and development (Kelsall et al., 2003). Médecins Sans Frontières/ Doctors Without Borders (MSF) was included as an INGO specializing in medical and humanitarian assistance.

The data comes from reports and statements produced by the selected INGOs and news articles released by these INGOs and is limited to organizational communications and news articles published between January 2020 and June 2022. The search strategy adapted the protocol for a systematic literature review, called the ‘preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis’ or PRISMA (Moher et al., 2009). Although such a rigorous method for a systematic review of published scholarly articles cannot be applied to grey literature (Higgins et al., 2019), this study modified PRISMA guidelines to improve the consistency and selection of data. News articles were identified through a university database using the organization name combined with the search terms ‘advocacy’ and ‘health’. Organizational data was collected from their websites in sections such as ‘policy papers’, ‘advocacy’, ‘opinion’ or ‘publications’. The search strategy included the terms ‘health’ and ‘COVID-19’ to identify relevant reports or statements.

Irrelevant news articles and organizational publications were screened by reviewing titles that lacked a focus on global health and advocacy. Then, the 99 remaining records were assessed against the following criteria: (1) public statements or papers published by a selected INGO; (2) with a focus on global health and health-related issues (e.g., health governance, vaccines and health care, water and sanitation, etc.); (3) published between January 2020 and June 2022; and (4) including information about advocacy agendas and activities during the COVID-19 pandemic. These criteria shaped decisions around inclusion and exclusion, and omitted nine (four news articles and five NGO documents) that did not explicitly discuss the INGO’s perspectives on health-related issues. A total of 47 news articles and 43 documents were selected for analysis. Figure 1 summarizes the search and screening process.

The collected data were summarized in Excel to record identified information by organizations and the data sources. Then, the contents were thematically analyzed using NVivo software. Identified themes and patterns were grouped into three overarching themes—‘advocacy frames’, ‘priority agenda and groups’ and ‘organizational contexts’.

Findings

Advocacy Frames for Global Health

Human Rights Frame

Most of the data reveals that the selected INGOs primarily drew on a human rights frame when promoting global health issues, particularly around vaccines and treatments. This frame appeals to normative and ethical values such as human dignity and equity. The review suggested the human rights frame as an alternative to the dual failure of the governmental and private sector in vaccine distribution, calling the failure “unacceptable” (MSF, Save the Children) and “vaccine injustice” (ActionAid):

Access to a Covid-19 vaccine is a human right no one should be denied... There will be no end in sight until rich countries stop hoarding vaccines, stop supporting pharma monopolies, and start facing up to their international obligation. (AA_org_3, 2021)

Millions of the world’s most vulnerable people are being left behind and are unable to protect themselves from COVID-19 because of nationalism, protectionism, and discrimination. (WV_org_5, 2021)

People’s lives are the top priority in the human rights frame, as illustrated in the catchphrase “putting people before profit”:

MSF calls on governments to take concrete steps to rethink and reform the biomedical innovation system to ensure that lifesaving medical tools are developed, produced and supplied equitably where monopoly-based and market-driven principles are not a barrier to access. It is time to prioritize saving lives instead of protecting corporate and political interests. (MSF_org_10, 2022)

Within the human rights framework, “availability, accessibility, acceptability, quality, participation and accountability” are suggested as essential elements of the right to health (UN OHCHR, n.d.). These elements were emphasized when development NGOs promoted equitable, universal and affordable access and distribution of vaccines and medical tools.

We will keep raising our voice to ensure that there is equitable distribution according to needs and vulnerability, rather than who can pay the most. (MSF_org_2, 2020)

The concept of acceptability was also addressed. MSF and World Vision emphasized the importance of “age-specific health education” (WV_org_3, 2020) and health information that dealt with “stigma and self-blame” (MSF_news_1, 2020) in a culturally appropriate way:

“A ‘corona’ is a crown, and the idea is that survivors of this virus in our community will wear their crowns with pride,” says a head of the Seniors’ Programme, a collective of elderly women… The team has also been combatting stigma through songs, composing anti-stigma lyrics and teaching these to clinic staff in facilities. (MSF_news_1, 2020)

The INGOs also emphasized the importance of the participation of local community-based organizations (MSF, Oxfam, World Vision) and vulnerable people, particularly women (ActionAid, Oxfam) and children (Save the Children) in decision-making processes.

These human rights-based advocacy strategies primarily employed “global compliance or/and legal mobilization” approaches (Gauri & Gloppen, 2012). Oxfam, ActionAid and Save the Children supported their arguments by referring to international conventions and agreements such as the Doha Declaration (MSF_news_2, 2020), the UN Conventions on the Rights of the Child (SC_org_6, 2021), Persons with Disabilities (AA_news_4, 2021), and Refugees and Stateless Persons (Oxfam_news_5, 2020), as well as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) and the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights.

Despite the general commitment to the human rights frame, some documents revealed a fair degree of skepticism about the likelihood of realizing equal rights in global health justice:

‘Fair and equitable’ vaccine distribution at the global level, in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, was never going to happen. In reality, the world was just not prepared in any meaningful way – legally, logistically, or politically – to manifest it. (WV_org_6, 2022)

This realization invited the necessity of pushing further to establish enforceable measures to convert the rights to health into reality:

We welcome the drive to have “equity” as the critical lens to apply – but we need to turn this from principles into concrete enforceable actions. (MSF_org_7, 2021).

Legal action was employed to push for the accountability of duty bearers such as the state and pharmaceutical companies:

It is crystal clear that unless legal tools like the TRIPS Waiver are adopted, many countries will continue to be at the mercy of patent-holding corporations that have the say over who gets to produce, who gets to buy, and at what price. (MSF_news_6, 2021)

In addition to the TRIPS agreement waiver being described as “game changing” (MSF_news_4, 2021), INGOs urged states to create an environment where corporations’ profit-driven practices could be regulated:

Oxfam is calling for policymakers to institute a Pandemic Profits Tax on excess corporate profits during this crisis. (Oxfam_news_2, 2020)

South African government needs to prioritize people’s health over pharma corporations’ assured profits through patent monopolies and finally reform its patent law... Medicines shouldn’t be a luxury.” (MSF_news_9, 2022)

Scientific Evidence Frame

In many cases, INGOs did not draw heavily on medical or economic science research to back up their advocacy, but acknowledged the importance of scientific evidence, particularly when they engaged with the public on a topic that was disputed. For example, medical evidence was useful for asserting the need for rapid and fair vaccinations:

Imperial College concludes that to save more lives (up to 38.7 million) there is no alternative but to rapidly adopt and scale up public health measures. (Oxfam_org_3, 2020)

The Omicron variant affirms what many of the world’s leading scientists, public health officials, doctors, nurses, and economists have been saying since the beginning of the pandemic: if we do not vaccinate the world as quickly as possible, COVID will continue to threaten us all. (Oxfam_news_9, 2021)

Further, INGOs used medical research to promote the protection of the most vulnerable, such as patients with existing medical conditions (MSF). MSF justified prioritizing the medically vulnerable to avoid “wasted effort and resources” (MSF_org_5, 2021):

Data from the Western Cape Department of Health during the first COVID-19 wave showed how certain comorbidities are associated with death from COVID-19, including diabetes, hypertension, HIV and TB. (MSF_org_11)

Refugees and stateless people (Oxfam, World Vision) were also identified as vulnerable, as they were excluded from health protections awarded to citizens. The excerpt below shows that refugees or stateless were medically and socially vulnerable due to their situations within social systems:

COVID-19 is highly infectious and will spread easily in places where there are unhygienic conditions, crowding, and where health services and monitoring are weak... This means that countries hosting high numbers of displaced people and refugees need special and urgent support. (WV_news_3, 2020)

Beyond referring to external medical research, some INGOs backed their claims with their own studies. For example, Oxfam analyzed the World Bank’s emergency health funding to conclude that it failed to strengthen the public health system (Oxfam_org_2, 2020) and compared the five main vaccines from the perspective of the global public good (Oxfam_org_5, 2021). World Vision also collected data from the ground to identify barriers to preventive measures (WV_org_3, 2020; WV_org_9, 2022) and to demonstrate the impact of the pandemic on vulnerable groups such as internally displaced people (WV_org_5, 2021; WV_news_8, 2021) and girls (WV_org_8, 2022). MSF’s research on potential manufacturers in lower-income countries has implications for future pandemics and other diseases:

MSF research has identified more than 100 manufacturers in Asia, Africa and Latin America with the potential to manufacture mRNA vaccines… More regions producing mRNA vaccines as an essential preparation against infectious diseases could strengthen the response not only to COVID-19 and future infectious diseases, but also, potentially, to existing ones such as malaria, tuberculosis and HIV. (MSF_news_8, 2022)

Security Frame

The frame that highlights security and national concerns was not explicitly referenced in the data analyzed. However, it was often combined with the human rights frame to emphasize the need for universal access to vaccines, through appealing to a shared interest in risk reduction:

They not only mean that the poorest people are vulnerable, they put the whole population at risk. When a virus affects the whole world, buying yourself out is not an option. (Oxfam_org_3, 2020)

We are worried that without universal, affordable and equitable access to medical tools, the pandemic will last longer, impacting not just people with COVID-19, but also the capacity of health systems to provide immunization, care and treatment for other diseases, causing more deaths and suffering. (MSF_org_6, 2021)

INGOs sometimes used words that incited fear and urgency, calling the COVID-19 pandemic “the biggest humanitarian crisis” (Oxfam_org_3, 2020) and the Omicron variant “a wakeup call” (Oxfam_news_9, 2021):

The clock is ticking and so many lives are at stake. (MSF_org_6, 2021)

We cannot afford to wait--any delay means that thousands more people will die, and the virus will continue to mutate (Oxfam_news_7, 2021)

This fear-based appeal was extended to anxiety around possible economic disruption:

Failures to make vaccines available to all, free of charge, will prolong the pandemic and the human and economic suffering attached to it. (AA_org_3, 2021)

The economic arguments for a global response could not be more evident, with estimates of a US$9.2 trillion hit to the global economy if vaccine nationalism is pursued… As stated by the heads of WHO and UNICEF, the failure to take a global approach will “cost lives and livelihoods, give the virus further opportunity to mutate and evade vaccines and will undermine a global economic recovery”. (SC_org_4, 2021)

Economic difficulty is noted as a central source of fear in Shiffman and Sharwar’s (2022) definition of securitization process. However, as suggested above, the IGNO communications analyzed in this study centered concerns about economic downturn around its impact on human suffering. This suggests that these INGOs’ definitions of ‘security’ are focused on ‘global human security’ and different from what is highlighted in more nationalistic security frames employed by governments and other international organizations (McInnes & Lee, 2012; Shiffman & Sharwar, 2022).

Prioritized Health Issues During the Pandemic

Protecting Vulnerable Populations

The frame that an organization employs decides its priorities (Shiffman & Shawar, 2022). Using a human rights frame indicates a focus on fairness and equality and this helps prioritize and define the people that lack these things—the most marginalized and disadvantaged groups (Hickey & Mitlin, 2009; Robinson, 2007). All five INGOs urged the global community toward greater accountability to the vulnerable and the marginalized, describing these groups as those who “face some of the highest risks but remain the lowest priority in national and global responses to the pandemic” (WV_org_5, 2021).

Identified priority groups include children (Save the Children, World Vision), elderly people (MSF), women (ActionAid, Oxfam), frontline health workers (ActionAid, MSF), high-risk patients (MSF, Oxfam), Indigenous peoples (ActionAid, Oxfam), asylum seekers and refugees (Oxfam, Save the Children, World Vision), and those in conflict-affected areas (MSF, Oxfam, Save the Children, World Vision) and remote communities (MSF). The vulnerability of these groups is highlighted in most of the communications, and intersectionality is often evident—for example, when writing about Indigenous women (Oxfam) and young girls (World Vision).

These groups are commonly suggested as lacking access to vaccines and care services, which are framed as basic human rights, and as suffering the brunt of pandemic impacts. These INGOs’ advocacy is primarily grounded in raising up the voices of people in lower-income countries, reflecting the principle of participation (Robinson, 2007). In particular, ActionAid, MSF and World Vision produced data and stories from people whose voices have been under-represented in global health governance.

Promoting Equitable and Affordable Vaccinations

Vaccinations for vulnerable and high-risk groups were spotlighted as an urgent issue for global health:

Solving this crisis will require systemic change, but an urgent, lifesaving first step is to fight the pandemic through free, fair, and equitable access to vaccinations… Global development bodies and platforms, UN agencies, governments, and pharmaceutical companies should work out a distribution plan for vaccines priced at-cost, and support countries in investing in production capacity, procurement, and strengthening of their health systems. (AA_org_5, 2021)

All INGOs called for fair and equitable access to vaccines, and this was often conceptualized as a global public good. One rationale was that public funding and contribution enabled the research and development of COVID-19 vaccines:

Moderna, Pfizer/BioNtech, Johnson &Johnson, Novovax and Oxford/AstraZeneca received billions in public funding and guaranteed pre-orders, including $12 billion from the US government alone. An estimated 97% of funding for the Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine came from public sources. (Oxfam_news_7, 2021)

Healthcare workers, patients, COVID-19 survivors and the general public have contributed enormously to clinical trials and other R&D activities on different therapeutics and vaccines. Yet many of the pharmaceutical corporations are striving to commercialize and monopolize scientific breakthroughs originating in public labs with public funding around the world. (MSF_org_1, 2020)

Another rationale was that public opinion in higher-income countries supported vaccine access for people in lower-income countries and government should be held accountable to this:

Across G7 nations, an average of 70% of people want the government to ensure vaccine know-how is shared, according to an analysis by the People’s Vaccine Alliance. (Oxfam_news_7, 2021)

Canadians have clearly told us that as a country we should be concerned for the needs of people beyond our borders... Canadians know we will not be safe until everyone is safe. (WV_news_8, 2021)

The TRIPS Waiver, which proposed temporarily waiving patent monopolies to allow generic vaccine production and more affordable prices, appeared as one of the core advocacy campaign requests to increase the supply of COVID-19 vaccines, diagnostics, and medicines.

The landmark TRIPS Waiver offers an expeditious option to overcome the legal barriers during the pandemic and could pave the way for diversified supply and production so that more affordable and sustainable access can be guaranteed. (MSF_org_8, 2021).

We don’t have enough vaccines for everyone and the biggest barrier to increasing supply is that a few profit-hungry pharmaceutical corporations keep the rights to produce them under the lock and key. (Oxfam_news_7, 2021)

ActionAid, MSF, Oxfam and Save the Children were among the prominent actors that urged higher-income countries to support the waiver proposal. They issued statements or media releases to influence positive changes in key meetings, as widely known as policy window (Shiffman & Smith, 2007), including the “G7 Summit” (AA_org_6, 2021), “G20 Summit” (SC_org_5, 2021), and the “foreign and development ministers meeting and the General Council of the World Trade Organization (WTO)” (MSF_news_6, 2021; Oxfam_news_7, 2021). Following these key events, some changes, such as the vaccine technology transfer hub announced in June 2021, were welcomed as “a positive milestone on the road to expanding vaccine manufacturing capacity in low- and middle-income countries” (MSF_news_8, 2022).

In addition to vaccine supply, vaccine hesitancy was pinpointed as a vaccination barrier by World Vision and Oxfam. Community-based approaches were suggested as effective in addressing the hesitancy issue, exemplified by “working with trusted civil society groups who have strong pre-existing links to these communities” (Oxfam_org_4, 2021) and “to use our global reach and grassroots connections to encourage vaccine acceptance and uptake” (WV_org_3, 2020). This confirms the extant literature that argues the importance of the community health system and workers in responding to the pandemic (Nelson, 2021).

Strengthening the Health System

Strengthening duty bearers’ accountability is prioritized in the human rights frame in order to address the underlying causes that hinder health justice (Robinson, 2007). As such, national health governance was one of the structural issues to address:

It will be hard to obtain a high level of vaccination coverage in these countries, even if we fix the issue of vaccine supply, because of the lack of a functioning healthcare system; insecurity linked to conflict. (MSF_org_5, 2021)

Countries with fragmented, privatized healthcare systems, from the United States to Kenya, are simply not up to the challenge. (Oxfam_org_3, 2020)

In addition to strengthening national health systems, for example, through universal health coverage (Oxfam, Save the Children), some INGOs supported “debt relief or cancellation” (AA_org_2, 2020; Oxfam_org_3 & Oxfam_news_3, 2020; SC_org_1, 2020) to increase financing for national public health in lower-income countries. To improve global health governance, some INGOs, particularly Save the Children and World Vision, called on greater financial commitments from governments to strengthen existing mechanisms such as COVAX and WHO. However, the excerpts below show a critique of this idea common to ActionAid, Oxfam and MSF:

Donations from rich countries are urgently needed to help save COVAX, but they will not be enough on their own. The need for donations is a symptom of a broken system, where vaccines have been made artificially scarce and hugely expensive. (AA_org_6, 2021).

Furthermore, these INGOs suggested proactive measures such as “highly progressive taxation of wealth and profits” (Oxfam_org_8, 2022) to hold the private sector accountable, as “voluntary measures by pharmaceutical companies” are not enough to ensure accessible and affordable health services (MSF_org_2, 2020). The below extract confirms the necessity of a revolutionary approach to global goods and services:

What this pandemic reveals is that there are goods and services that must be placed outside the laws of the market. (Oxfam_org_3, 2020)

Organizational Factors

Identities and Associated Values

Earlier sections discussed the prominent use of the human rights frame among the INGOs that were reviewed. ActionAid, Oxfam and Save the Children in particular claim that their work is grounded in human rights—they pursue “rights-based goals and agenda” (Oxfam_news_1, 2020), address “suppression of human rights” (AA_news_5, 2021) and advance “rights-based health services” (SC_org_3, 2021). These INGOs adapted their advocacy agendas and strategies to respond to the pandemic in line with their human rights-based approaches.

References to human rights are not evident in MSF’s and World Vision’s literature. MSF identifies as a “medical humanitarian organization” (MSF_org_2, 2020), and World Vision claims its expertise is in “humanitarian health” (WV_org_2, 2020). Their greater focus is on humanitarian assistance to human suffering and the concept of human rights is employed to highlight the duty bearers’ accountability to protection. Yet despite these differences between humanitarian and human rights approaches, these humanitarian INGOs increasingly use the human rights frame when approaching advocacy (Darcy, 2004; Lakoff, 2010).

Histories and Networks

All the INGOs that were reviewed strongly advocated for equitable and affordable vaccines and treatments, in line with their extensive and historical engagement with global health projects and campaigns. For example, MSF highlighted its “long history of managing health emergencies and infectious disease outbreaks” (MSF_org_2, 2020) and “previous experience through its long-standing HIV and tuberculosis (TB) projects” (MSF_news_1, 2020). MSF and Oxfam have also led the movement for access to essential medicine since 1999 (Nelson, 2021):

For many years Oxfam has campaigned for universal public healthcare for all, and against the privatization of health systems. (Oxfam_org_3, 2020)

For MSF and Oxfam, the TRIPS waiver proposal was at the top of their advocacy agenda during the pandemic, aligning with their history of access campaigns. Oxfam, ActionAid and Save the Children joined the ‘People’s Vaccine Alliance’. The alliance, a coalition of over 100 health, humanitarian and human rights organizations, has called for free vaccines for all since May 2020, grounded in their collective belief in access to healthcare as a basic human right (The People’s Vaccine, n.d.). ActionAid, Oxfam and Save the Children explicitly called for “the people’s vaccine” in line with the alliance’s arguments and demands (AA_org_3, 2021; Oxfam_org_4, 2021), and helped introduce and promote the activities of the alliance (AA_org_5, 2021; Oxfam_news_7, 2021; SC_news_8). In addition to the People’s Vaccine Alliance, studied INGOs also worked with diverse networks to amplify the voices of civil society, working within the human rights frame that calls for shared language for collaborative advocacy (Hickey & Mitlin, 2009).

The INGOs also worked in partnership with other international organizations with their extensive experience in global health. Save the Children built a partnership with Gavi to increase access to immunizations based on their joint specialty in children’s health (SC_news_8, 2021). World Vision also highlighted its expertise as “a top performing, A-rated partner of the Global Fund” with “an advisory role in COVAX” based on its experience responding to other crises and effectively engaging with communities (WV_org_3, 2020).

In the case of MSF, its engagement with the Humanitarian Buffer (HB) in partnership with the COVAX Facility was a bitter experience: “an opaque, unwieldy legal framework placing an excessive liability on field-based humanitarian organizations carrying out the operations”, which led it to conclude the HB as “failing its mission to support people hit by the pandemic and struggling to access immunization” (MSF_org_8, 2021).

Discussion

The study findings indicate that a human rights frame was used by all the organizations that were studied in their advocacy for global health justice during the COVID-19 pandemic, though the degree to which they committed to this frame varied. The prevalence of the human rights frame confirms that civil society organizations are key to mainstreaming human rights in global health systems (Meier & Gostin, 2018), which are otherwise often driven by technical approaches and business interests (Gideon & Porter, 2016).

The human rights frame has both intrinsic and instrumental values for global health advocacy. Framing the TRIPS waiver issue as a battle between people and profit asks audiences to consider and prioritize the right to be healthy against intellectual property rights (Johnson, 2022). In this frame, intellectual property rights are represented as profit-driven, in opposition to people-centered rights founded on moral and ethical values (Forst, 2010). To further this people-centered advocacy agenda, the INGOs gained legitimacy and justification for their positions by calling for compliance with international conventions and agreements that recognize the fundamental right to health for everyone, including the right to enjoy scientific advancement and its benefits (Article 27 of the UDHR).

Their advocacy targets were duty bearers—primarily nation states that are signatories to international conventions and WTO members, as well as the private sector. Despite a lack of enforceability, human rights advocacy has been effective for making duty bearers accountable by requesting global compliance and mobilizing collective actions (Gauri & Gloppen, 2012; Nixon et al., 2008). In addition to making health a claimable right, the human rights frame also promotes working on determinants of health, which can directly and indirectly influence health (Gruskin et al., 2007). This study confirms previous studies that the human rights frame assists in identifying priority issues, defining duty bearers and their obligations, and collaborating for alternatives to the current laws and policies that hinder the right to health (Hickey & Mitlin, 2009; Kindornay et al., 2012; Robinson, 2007).

The INGOs that were studied strengthened the human rights frame by combining it with other frames in a complementary way. This is different from a previous study that the human rights frame is often deployed to complement other frames (McInnes & Lee, 2012). INGOs used the scientific evidence frame by referencing credible scientific studies to support their positions, particularly when engaging with the public over the necessity for universal and fair vaccination, as well as when presenting the result of their own research to produce valuable data on vulnerable populations, which are often excluded or ignored by policymakers. The INGOs’ participatory and community-centered approaches also enabled neglected voices to be heard in policy arenas (Gideon & Porter, 2016), and their role in translating and amplifying locally produced information and circulating it in global settings enhanced the legitimacy and influence of their advocacy (Jordan & Van Tuijl, 2000; Noh, 2017). Meanwhile, the security frame, which is often used in times of crisis (Duffield, 2014; Nunes, 2016) and can increase otherness, aid securitization, and nationalism (Brown, 2021; Noh, 2022), was occasionally used by the INGOs, but from a more humancentric angle. In this study, the INGOs did sometimes appeal to fear and urgency, emphasizing the need to take immediate actions for shared interests of reducing risks, but their definition of security was different from that used by states and international institutions—a goal, rather than a threat.

The present study suggests that INGOs’ health advocacy can be better understood by using different frames, including deontological and teleological ethics. Deontological ethics highlight moral duties, including human rights and social justice, while teleological ethics expose adverse consequences with an appeal to urgent responses (Duffield, 2014). Given the dominance of the human rights frame, the other frames of scientific evidence and security serve to support INGOs’ prioritized ethical imperatives, with INGOs highlighting human security as a shared goal rather than a threat. In terms of scientific framing, INGOs can use their highly valued technical interventions and tangible outcomes (Nelson, 2021) to deploy data to leverage their claims and support calls for action and change.

INGOs’ advocacy priorities during the pandemic should also be understood as emanating from their original mandates and focus areas (Szent-Iványi, 2022). For example, one of the most prominent agenda items for most of the reviewed INGOs was the TRIPS Waiver campaign. The essence of their claims in this campaign was that vaccine-related knowledge and technology should be regarded as global public goods (Peacock, 2022). Although the COVID-19 vaccines do not satisfy the current definition of public goods due to the rivalrous and exclusive nature of patented medicines (Saksena, 2021), the INGOs point out that it is the patent system itself that means the vaccines are exclusive—and that this system should change. The campaign is another fight in the long battle that global civil society organizations, including MSF and OXFAM, have waged to increase access to medicine since the 1990s (Nelson, 2021). In addition, all reviewed INGOs identified structural barriers that stand in the way of their missions, challenging the current economic and political powers to bear global accountability for the vulnerable (Szent-Iványi, 2022) and promoting transformative changes in health-related corporate policies and practices (Anaf et al., 2020). These advocacy agendas appear to be shaped by their organizational identities as champions of human rights and humanitarianism.

The INGOs also consolidated their positions and visibility through associations and networks. Existing studies note the importance of advocacy networks in amplifying resources and political opportunities and putting specific issues on the global agenda (Alexander et al., 2023; Smith & Shiffman, 2016). Framing is critical for attracting like-minded organizations and aligning claims with norms and values shared in the network (Shiffman & Shawar, 2022). In this study, the human rights frame confirms its grounding values as well as its strategic values.

This study’s focus on INGO advocacy framing simplifies the complex phenomena of global health decision-making and does not consider the fragility and efficacy of the human rights frame as a motivating factor among certain duty bearers—particularly governments and policy makers that are trending away from engaging with normative ideas of global public goods and obligations. Another limitation of this research is that the INGOs’ publicly available claims may not reflect the entirety of their roles in advancing global health justice. However, this research sheds light on the role of INGOs as transnational advocates in global health, which reaches beyond their service provider roles, and draws attention to the framing they use to communicate and the power of this framing—an under-researched area of global health policy-making. The COVID-19 pandemic was a catalyst for new ideas that challenge the current political and economic system, serving as a “critical juncture” (Green, 2020). This study presents the potential for humanitarian and development NGOs to open up new opportunities for global health justice by collaborating with other global health actors using a frame that emphasizes human rights over profit margins.

Conclusion

This research finds that international humanitarian and development NGOs actively promote global health justice through their advocacy activities. Their primary agendas during the COVID-19 pandemic included protecting the most vulnerable and marginalized, advancing equitable access to vaccines and technology, and strengthening the health system. These agendas were primarily grounded within a human rights frame, complemented and supported by scientific evidence and security frames. Their decisions around advocacy strategies stem from their organizational identity, mandates, histories and networks, which emphasize moral duties and responsibility to others.

This study suggests a stronger role for development INGOs in promoting global health justice as advocates beyond their missions as service providers. Their transnational influence can enhance the voices of the marginalized and challenge structural barriers that impede global health justice. The human rights frame equips INGOs with fundamental values, a lens through which to interpret situations and analyze impacts, and effective advocacy strategies. ‘Putting people first’ is an essential perspective, particularly when concerns about national interest and profit dominate debates on global public good and health justice. This paper concludes that the human rights frame can offer an alternative way forward in times of rising nationalism and disaster capitalism.

References

Alexander, J., Elías, M. V., & Hernández, M. G. (2023). CSO advocacy and managing risk in hybrid regimes: An exploration of human rights organizations in Colombia. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-023-00601-y

Anaf, B. F., Fisher, M., & Friel, S. (2020). Civil society action against transnational corporations: Implications for health promotion. Health Promotion International, 35(4), 877–887.

Benford, R. D., & Snow, D. A. (2000). Framing processes and social movements: An overview and assessment. Annual Review of Sociology, 26(1), 611–639.

Brass, J., Longhofer, W., Robinson, R. S., & Schnable, A. (2018). NGOs and international development: A review of thirty-five years of scholarship. World Development, 112, 136–149.

Brown, S. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 on development assistance. International Journal, 76(1), 42–54.

Capano, G., Howlett, M., Jarvis, D. S., Ramesh, M., & Goyal, N. (2020). Mobilizing policy (in) capacity to fight COVID-19: Understanding variations in state responses. Policy and Society, 39(3), 285–308.

Carpenter, R. C. (2007). Setting the advocacy agenda: Theorizing issue emergence and nonemergence in transnational advocacy networks. International Studies Quarterly, 51(1), 99–120.

Correa, C.M., & Syam, N. (2022). The WTO TRIPS decision on COVID-19 vaccines: What is needed to implement it? South Centre Research Paper. 169.

Darcy, J. (2004). Human rights and humanitarian action: A review of the issues. In background paper prepared for Human Rights and Humanitarian Action—Humanitarian Policy Group Background Paper (UNICEF) Workshop, Geneva, 1–17 April 2004.

Davies, L. (2022). Compulsory licensing: an effective tool for securing access to Covid-19 vaccines for developing states? Legal Studies, 1–18.

Dolšak, N., & Prakash, A. (2022). NGO Failure: A Theoretical Synthesis. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 33(4), 661–671.

Duffield, M. (2014). Global governance and the new wars: The merging of development and security (2nd ed.). Zed Books.

Forst, R. (2010). The justification of human rights and the basic right to justification: A reflexive approach. Ethics, 120(4), 711–740.

Gauri, V., & Gloppen, S. (2012). Human rights-based approaches to development: Concepts, evidence, and policy. Polity, 44(4), 485–503.

Gideon, J., & Porter, F. (2016). Challenging gendered inequalities in global health: Dilemmas for NGOs. Development and Change, 47(4), 782–797.

Goffman, E. (1974). Frames of analysis. An essay on the organization of experience. Northeastern University Press.

Green, D. (2020). Covid-19 as a critical juncture and the implications for advocacy. Global Policy, 23(April), 1–16.

Gruskin, S., Mills, E. J., & Tarantola, D. (2007). History, principles, and practice of health and human rights. The Lancet, 370(9585), 449–455.

Hickey, S., & Mitlin, D. (Eds.). (2009). Rights-based approaches to development: Exploring the potential and pitfalls. Kumarian Press.

Higgins, J. P., Thomas, J., Chandler, J., Cumpston, M., Li, T., Page, M. J., & Welch, V. A. (Eds.). (2019). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Wiley.

Johnson, S. (2022). International rights affecting the COVID–19 vaccine race. University of Miami Inter-American Law Review, 53(2), 145–185.

Jordan, L., & Van Tuijl, P. (2000). Political responsibility in transnational NGO advocacy. World Development, 28(12), 2051–2065.

Kelsall, T., & Mercer, C. (2003). Empowering people? World vision & ‘transformatory development’in Tanzania. Review of African Political Economy, 30(96), 293–304.

Kindornay, S., Ron, J., & Carpenter, C. (2012). Rights-based approaches to development: Implications for NGOs. Human Rights Quarterly, 34(2), 472–506.

Lakoff, A. (2010). Two regimes of global health. Humanity: an International Journal of Human Rights, Humanitarianism, and Development, 1(1), 59–79.

Levine, A. C., Park, A., Adhikari, A., & Heller, P. (2023). The role of civil society organizations (CSOs) in the COVID-19 response across the Global South: A multinational, qualitative study. PLOS Global Public Health, 3(9), e0002341.

Lindenberg, M., & Bryant, C. (2001). Going global: transforming relief and development NGOs. Kumarian Press.

Magrath, B. (2014). Global norms, organizational change: Framing the rights-based approach at ActionAid. Third World Quarterly, 35(7), 1273–1289.

Mantilla, K. K. & Barona, C. C. (2022). COVID-19 vaccines as global public goods: Between life and profit, South Centre Research Paper. 154.

McInnes, C., & Lee, K. (2012). Framing and global health governance: Key findings. Global Public Health, 7(2), 191–198.

Meier, B. M., & Gostin, L. O. (Eds.). (2018). Human rights in global health: Rights-based governance for a globalizing world. Oxford University Press.

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA Statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097.

Nelson, P. J. (2021). Global development and human rights: The sustainable development goals and beyond. University of Toronto Press.

Nixon, S., & Forman, L. (2008). Exploring synergies between human rights and public health ethics: A whole greater than the sum of its parts. BMC International Health and Human Rights, 8, 1–9.

Noh, J. E. (2017). The role of NGOs in building CSR discourse around human rights in developing countries. Cosmopolitan Civil Societies: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 9(1), 1–19.

Noh, J.-E. (2022). Constructing ‘others’ and a wider ‘we’ as emotional processes. Thesis Eleven, 170(1), 43–57.

Nunes, J. (2016). Ebola and the production of neglect in global health. Third World Quarterly, 37(3), 542–556.

Obeng-Odoom, F. (2012). Health, wealth and poverty in developing countries: Beyond the state, market, and civil society. Health Sociology Review, 21(2), 156–164.

Peacock, S. J. (2022). Vaccine nationalism will persist: Global public goods need effective engagement of global citizens. Globalization and Health, 18(1), 1–11.

Plipat, S. (2005). Developmentizing human rights: How development NGOs interpret and implement a human rights-based approach to development policy (Doctoral Dissertation). The University of Pittsburgh.

Robinson, M. (2007). The value of a human rights perspective in health and foreign policy. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 85, 241–242.

Saksena, N. (2021). Global justice and the COVID-19 vaccine: Limitations of the public goods framework. Global Public Health, 16(8–9), 1512–1521.

Sell, S. K. (2001). TRIPS and the access to medicines campaign. Wisconsin International Law Journal, 20(3), 481–522.

Shiffman, J. (2007). Generating political priority for maternal mortality reduction in 5 developing countries. American Journal of Public Health, 97(5), 796–803.

Shiffman, J., & Shawar, Y. R. (2022). Framing and the formation of global health priorities. The Lancet (british Edition), 399(10339), 1977–1990.

Shiffman, J., & Smith, S. (2007). Generation of political priority for global health initiatives: a framework and case study of maternal mortality. The Lancet (british Edition). [online], 370(9595), 1370–1379.

Smith, S. L., & Shiffman, J. (2016). Setting the global health agenda: The influence of advocates and ideas on political priority for maternal and newborn survival. Social Science & Medicine, 166, 86–93.

Szent-Iványi, B. (2022). European civil society and international development aid: organisational incentives and NGO advocacy. Taylor & Francis.

The people’s vaccine (n.d.). Who we are. https://peoplesvaccine.org/ (Accessed on 22 October 2022)

UN OHCHR (Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights) (n.d.). OHCHR and the Right to Health. https://www.ohchr.org/en/health (Accessed on 20 October 2022)

Van der Veen, A. M. (2011). Ideas, interests and foreign aid. Cambridge University Press.

Yoo, E. (2022). The impact of INGO ties on flows of aid for women’s health in the developing world. International Journal of Comparative Sociology, 64(3), 249–277.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions. This research has been supported by World Vision Korea. The funder has no role in study design, data collection and analysis, and preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

An earlier version of this manuscript was submitted to the funder to meet the funding requirement. Other than that, there no conflict of interest to report. The research is independent of the funder.

Ethical Approval

This material is the authors' own original work, which is not currently being considered for publication elsewhere.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Noh, JE. The Fight for Global Health Justice: The Advocacy of International Humanitarian and Development NGOs During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Voluntas (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-023-00630-7

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-023-00630-7