Abstract

Within nonprofit organizational studies, there has been a long-standing interest in democratic governance as ways of building political participation, civic skills and fostering inclusion. While established approaches to democratic governance have many benefits, existing research points to numerous challenges, including apathy and oligarchization. This paper explores an alternative form of democratic governance, sociocracy. Sociocracy, sometimes called dynamic governance, is organized around four key elements: circular hierarchy, consent-based decision-making, double linking, and practices to foster inclusivity and voice, a unique blend which distinguishes it from other forms of democratic governance. This article explores the implications on workplace democracy that a nonprofit organization experienced when limiting it. We find that sociocracy offers many benefits, including empowering members and reducing the risk of domination, and also highlights the many challenges that can accompany the implementation of sociocracy, particularly how four forms of inequality contribute to those challenges.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Drawing inspiration from Alexis de Tocqueville ([1840]2003), nonprofit research has long been interested in questions around the impact of democratic governance within nonprofit organizations (NPOs) (Lee, 2022; Dodge & Ospina, 2016; Dekker, 2019; Renz et al., 2022). De Tocqueville espoused a general theory of association that considered participation within NPOs as a central way to develop democratic skills and capacity. Building on this ambition, recent interest in democratic governance sees NPOs as member-based organizations (Guo et al., 2014; Spear, 2004) that have the ability to act as schools of democracy (Dodge & Ospina, 2016), by socializing their members into democratic participation.

An important contemporary strand of research on democratic governance focuses on the outcomes of participatory practices, particularly their impact on fostering civic skills (Torpe, 2003), improving voice and equality, or encouraging active participation in the political sphere (Verba et al., 1995). As such, participatory democratic governance aims to support “members [to] actively interact with others within voluntary organizations, [so that] they learn and practice communication skills, understand diverse opinions, and build trust in others” (Lee, 2022, p. 242 emphasis in original). Yet some empirical literature highlights persistent challenges in practice (Guo et al., 2014), including low levels of participation (Van Puyvelde et al., 2016) and persistent inequalities within decision-making (Torpe, 2003). Overall, Lee argues, the empirical literature is “inconclusive”, in assessing the impact of NPOs on civic engagement, which, he states “may stem from the heterogeneity of voluntary organizations and [models of] political participation. Studies have yet to consider the characteristics of diverse types of voluntary organizations and types of political participation” (2022, p. 242). Therefore, we cannot take for granted that NPOs automatically support democratic participation.

Recognizing these persistent challenges, a recent survey of ARNOVA members suggested researchers should explore “the benefits and problems inherent in different governance models (e.g., sociocracy, less hierarchical models)” (Renz et al., 2022, pp. 265S–266S). Taking up this challenge in this article, we focus on how sociocracy could reimagine governance of nonprofit organizations. Our analysis concentrates on the benefits that sociocracy claims to encourage such as inclusivity, but also the problems, particularly around hidden forms of exclusion. Thus, our guiding research question is: what are the opportunities and challenges of introducing sociocracy into NPOs?

We begin by reviewing the challenges of democratic governance in NPOs. Then, we introduce sociocracy as an alternative form of democratic governance organized around four key elements: circular hierarchy, consent-based decision-making, double linking, and practices to foster inclusivity and voice. We then present our methods for our study of Phoenix Housing Community (PCH), a nonprofit introducing sociocracy, reflecting on the opportunities and challenges of implementing sociocracy within a nonprofit. Learning from our case study, we argue that sociocracy is an emerging form of democratic governance that, through its unique blend of practices, offers opportunities for inclusion, while contending with four types of inequalities, namely that of status, expectations, application and capacities. Based on these findings, we conclude by drawing out some of the practical consequences for practitioners seeking to use sociocracy.

The Challenges of Democratic Governance Within NPOs

While the merits of democratic governance as a mechanisms to support NPOs acting as schools of democracy has been heralded (Dodge & Ospina, 2016), the literature has also recognized challenges (i.e. Van der Meer & van Ingen, 2009), including the relatively low levels of perceived member influence (Torpe, 2003) and limited knowledge about how leadership positions can be accessed, and oftentimes limited active engagement of members (Spear, 2004; Van Puyvelde et al., 2016).

Participation in NPOs is not enough. Recent literature suggest we should “focus on representation, participation, and power in governance practices, and help understand how these dynamics affect nonprofit organizations” (Van Puyvelde et al., 2016, p. 897). One strand of this work focuses on organizations’ ability to reflect their organizational values, such as equity, participation, and collaboration, within their organizational practice (King & Land, 2018). Another strand draws attention to power dynamics, representation, and equity, raising questions such as “who is allowed access to governance, whose voices are at the table, whose perspectives are represented by others, and to what degree”? (Guo et al., 2014, p. 47). Democratic governance, therefore, needs to be attentive to the organizing practices through which voice, equity, and participation are structured.

Drawing on the broader workplace democracy literature (King & Griffin, 2019), one fruitful approach has been to pay attention to organizational structures that take more explicitly democratic ethos, such as practices around self-management, horizontal or collective decision-making (Diefenbach, 2019). Specifically such work also focuses on the participation mechanisms built into these practices and how they inform decision-making (Eikenberry, 2009; Enjolras, 2009). Such approaches provide the additional possibilities of deeply democratic practices of full participation, where everyone impacted by a decision has the right to make the decision (Leach, 2016; Pateman, 1970; Reedy et al., 2016). Practices developed within new social movements such as those of Occupy! offer models of participatory practice for more formalized nonprofits (Diefenbach, 2019; King & Land, 2018; Reedy et al., 2016). However, these more democratic and participatory ways of organizing are often prone to challenges that can be more pronounced in NPOs. Notably, consensus-based decision-making—a common practice of horizontal organization forms—is widely criticized for being slow, and disjointed (Reedy et al., 2016), potentially making hierarchical organizations more appealing, particularly for volunteers who might be motivated by social goals rather than involvement in endless meetings (King & Griffin, 2019). Democratic organizational forms are also argued to be prone to oligarchization (Diefenbach, 2019) or the tyranny of structurelessness, where informal hierarchies and undesirable power dynamics become reproduced (Freeman, 1972). Finally, there is a concern that by democratizing decision-making and getting all members of the organization involved, in particular inexperienced volunteers, inappropriate decisions would be taken which could have negative long-term consequences for the organization (for a counter-argument see Leach, 2016). Thus researchers, and many practitioners, have been exploring alternative forms of democratic governance to tackle these persistent challenges while maintaining the democratic ethos. One such approach is sociocracy.

Sociocracy as a Form of Democratic Governance

This article focuses on a system of organizational governance called sociocracy, also known as dynamic governance. Sociocracy “is an inclusive method of organizational governance based on the equivalence of all members of the organization … [that is] … the equal valuing of each individual, in distinction to valuing for example, the majority or the management more highly” (Buck & Villines, 2007, pp. 242–249). Sociocracy was developed by Kees Boeke in 1945, a Dutch civil engineer, Quaker and pacifist who created a self-governing community of almost 400 students and teachers (Buck & Villines, 2007). Starting in the 1960s Gerard Endenburg then took the idea of sociocracy to his engineering company, Endenburg Electrotechniek, to achieve the first full implementation by 1984 (Endenburg, 2023; Rau & Koch-Gonzalez, 2018; Romme, 1995). Drawing on the Quaker roots, within this way of organizing vertical hierarchy, is rejected and replaced by “self-government that rejects majority voting” requiring instead decisions via consent (Boeke, 2007, p. 192), based on collective wisdom (Romme, 1995). Boeke (2007) argues this form of self-government is based on three fundamental principles: (1) all members must be considered, (2) solutions must be sought which everyone accepts, and (3) all members must act according to these decisions.

While some of these elements are familiar to those who have experience within horizontal democratic organizations (e.g. Kokkinidis, 2015; Maeckelbergh, 2012), they differ in subtle yet important ways that, collectively, make sociocracy distinct. Sociocracy is based on consent, rather than consensus; it is structured through circular forms of hierarchy, rather than flat (horizontal) organization; it has clear domains where decisions are made against these domains through small groups, rather than decision-making made by the collective. It is the combination of these features which make it unique. We now explore each of these factors.

Circular Hierarchy with Clear Domains

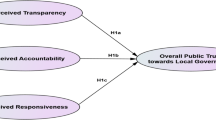

Sociocracy is a democratic form of circular hierarchy, where self-governing circles take on specific tasks and feed up and down to circles on different levels (Buck & Villines, 2007; Romme, 1999). As much authority as possible is given to specific circles, which have full authority within their domains. Circles usually have around 5–7 members. Within each circle, roles like leader, delegate (to the larger parent circle), and secretary are clearly defined. A general circle connects all the circles together and a mission circle focuses on the overall aims of the organization (Fig. 1).

Importantly, membership of circles is not fixed; people can rotate between them, with role holders selected through specific type of election (Rau & Koch-Gonzalez, 2018). Rather than removing hierarchy as is oftentimes emphasized in horizontal democratic organizations (e.g. Kokkinidis, 2015), in sociocracy there is a hierarchy of circles, making such hierarchies more transparent and fluid, minimizing possible abuses of power. Individuals can also be members of multiple circles, which helps further break up hierarchies, while maintaining clarity around domains.

The Use of Consent

Sociocracy focuses on efforts to make decision-making body effective and inclusive. Decision-making processes are meant to be explicit, transparent, and procedurally driven, involving three key steps: (1) picture forming, where the scope of the decision are considered, (2) proposal shaping, and (3) consent process (see Rau & Koch-Gonzalez, 2018). Importantly, decision-making is based on consent rather than consensus (Rau & Koch-Gonzalez, 2018). Endenburg adapted the Quaker consensus principle of ‘full agreement’ to consent, defined as no objections to a decision (Romme, 1995). According to this approach, individuals can object to a decision based on a concern that the proposal will not enable the circle to carry out its aim. Objections help surface and proactively address concerns and arguments (Buck & Villines, 2007). Additionally, by agreeing that a proposed decision is “good enough for now, safe enough to try” (Rau & Koch-Gonzalez, 2018, p. 4), consent is more action oriented than consensus, helping individuals balance their interests with those of their peers (Rau & Koch-Gonzalez, 2018, p. 4).

Double Linking

Organizations adopting sociocracy use a circular governance structure, which is both top-down and bottom-up simultaneously. Through a process called double-linking (see Fig. 2), the lead link from the parent circle takes the concerns of the higher circle into the lower circle, and the delegate from the ‘lower’ circle will report to the higher circle what decisions have been made. This creates a flow of power to create a circular hierarchy.

Double linking connects higher and lower circles, ensuring representatives are selected in an election-like process to sit on each, maintaining feedback and feed-forward loops and improving learning. In this sense, circles “that govern work units are linked by at least two people who provide direction (a leading function) and feedback (a measuring function) between the circles. This design establishes and maintains a dynamic process that keeps the whole organization responsive and open to change” (Buck & Villines, 2007, p. 86). While linking roles are sometimes used in other horizontal democratic organizations like delegates from regional assembly reporting on their discussions to a general assembly (e.g. Maeckelbergh, 2012), the systematic use double linking is a unique feature of sociocracy and links with the hierarchy of domains.

Practices to Foster Inclusivity and Voice

A final central feature of sociocracy is its commitment to an inclusive environment (where “every voice matters”) and establishing a community where all feel confident to speak out. This relies on the guiding principle of equivalence in which “no one is ignored…everyone’s needs matter equally—regardless of a person’s role or status” (Rau & Koch-Gonzalez, 2018, p. 4). To achieve this, sociocracy operates through a closely connected set of practices, including highly structured meetings using facilitators and circular rounds. While rounds and facilitation are not unique to sociocracy, the formalized steps of clarifying questions, reactions and consent, provide structure that can enable more inclusivity in at least ensuring that every voice is heard (Griffin et al., 2022). Furthermore, the feedback sessions and performance reviews, particularly with the version of sociocracy infused with Non-Violent Communication, seek to understand different individuals needs and foster mutual understanding (see Rau & Koch-Gonzalez, 2018, pp. 151–174 for a discussion).

In light of these elements, proponents of sociocracy have espoused many benefits. While evidence is largely anecdotal, proponents argue that sociocracy can also improve the quality of decision-making by entrusting decision-making to those who have the right knowledge and responsibility for implementation (Buck & Villines, 2007; Romme, 1995). Sociocracy is also seen as a promising way of reducing inequalities in organizations given its emphasis on transparency, equal access to information, meeting structure, and use of consent (Buck & Villines, 2007; Rau & Koch-Gonzalez, 2018). Finally, proponents highlight its contributions to participation and empowerment. Distributed leadership is at the heart of sociocracy (Rau & Koch-Gonzalez, 2018), with an emphasis on avoiding “ossification at the bottom and burn-out at the top by involving everyone in steering the organization toward its aim” (Buck & Villines, 2007, p. 93). Participation rights to decision-making are granted to all members within their circle related to their specific domain. They are all empowered, and expected, to participate in decisions involving topics including the design of work processes, the function and task descriptions of circle members, and the circle’s development plans (Buck & Villines, 2007).

However, much of the relatively limited research on sociocracy emphasizes its positive attributes, with less attention paid to its tensions and challenges, particularly within NPOs. Given this novel account of democratic governance therefore, the central question we ask is: what are the opportunities and challenges of introducing sociocracy into a nonprofit organization? It is to this question that we now turn.

Methods

To study this research question, we adopted a holistic single-case study design (Yin, 2014) of Phoenix Co-housing (PCH). PCH is a self-governing nonprofit housing community located in the Northwestern USA. Yin (2014) highlights several uses for which single-case study designs are appropriate, two of which are particularly relevant to our purposes: to capture the more mundane details and circumstances of a phenomenon of interest, and to offer critical insights about a phenomenon of interest that can challenge and extend extant insights. PCH are a particularly interesting case of sociocracy as all members of the community were new to sociocracy (meaning everyone had the same level of experience—so we could not discount challenges as a result of differential levels of knowledge). Furthermore, because PCH are a community, individuals were continually practicing sociocracy. The members engaged with sociocracy in a deeper way than say a NPO where individuals (particularly volunteers) might simply participate for a few hours a week and not adjust to the different practices as a result of temporary participation.

PCH was founded in 2015. Construction began in mid-2016 with residents moving-in around 2017. At the time of the research, there were 25 households in the community with approximately 40 residents. The legal structure of the community is as a ‘not-for-profit’ homeowners association and an annual budget over $150,000 per annum. Residents make an approximate $500 contribution for water, garbage collection and other facilities depending on the size of their house. The average cost of a house at PCH typically ranges from $300,000 to $700,000. As houses become available in the community, they are advertised through the quarterly newsletter and there is an open house each spring for prospective new residents. Individuals or couples wishing to join are then encouraged to attend community meals and sociocratic work meetings to understand the collective and participatory implications of doing so. The mission statement of the co-housing community is “to promote enjoyment and enrichment of our lives guided by shared responsibility and authority”.

To explore sociocracy at PCH, we gathered three main data sources: observations, interviews, and archival documents from the website. Martyn spent four days in the community as part of a wider study into democratic practices within organizations. Prior to joining, he had a one-hour telephone call with one of the founders and while at PCH he participated in events, observed their practices, and spent time with the members, getting a feel for the way that the co-housing organization operated. Throughout these four days, he was engaged in much of the daily life, sharing meals, helping with tasks like gardening, and participating in evening events like poker games. These experiences enabled him to listen and talk to the members about their experiences informally, including why they joined and what their experiences where within the community. He also attended four general circle meetings, observing their practices although not participating in decision-making. These observations were summarized in a 10,548 word field diary.

By spending time with the co-housing community, Martyn gained insights into the views of members helping contextualized the understanding how the practices were experienced, the strengths of sociocracy and challenges they faced. He conducted 16 interviews with 5 men and 11 women, who had been involved between 6 months and 5 years, to gain a broad view from members who were considered founders more recent arrivals. Moreover, drawing on his knowledge through the observations (from the initial meeting he observed on day one and guided by interviews conducted), he sought to interview people who had a range of views on sociocracy, from those that championed it to those seeming more skeptical.

The interviews were conducted in people’s homes where they felt most relaxed to be frank about their experiences and lasted approximately 60 minutes. They were all recorded and professionally transcribed. The interviews were designed to explore how the participants experienced sociocracy within PCH. The first part of the interview gave a background to the participant and why they joined the housing community, with the latter part examined in more detail their experiences within PCH. Questions included for instance: “What were your first impressions of using sociocracy in the governance of PCH?”, “What, if anything, did you find most rewarding/difficult in using sociocracy?” Martyn pressed, in particular, for examples of this occurring in practice. The interviews were conducting as conversations, which allowed interesting themes to be explore, particularly around the experiences of how sociocracy occurred in practice.

The data were coded by Martyn using an iterative data analysis strategy (Locke et al., 2022) developed in conduction with Daniel, grounded in five central guiding questions. The first guiding question was: “what were the aspirations/concerns of members of PCH in adopting sociocracy?” This provided us the context to understand the background to PCH and why they were bringing in sociocracy as a form of democratic governance. The next four guiding questions focused broadly on how participants experienced the four abovementioned elements of sociocracy: circular hierarchy with clear domains, the use of consent, double linking, and practices to foster inclusivity and voice.

For each of these guiding questions, the coding began with a process of open coding. For example, the data fragment “Some people feel they’re not in as deeply as others might be. Some folks have the vocabulary of a higher circle” was coded as “difference in voice” as it captured the asymmetry felt between different participants’ capacity to contribute. Through a process of constant comparison among the data fragments and codes, he identified connections among the codes (such as “difference in voice” and “lack of status”) that generated higher-order analytic categories (such as “inequality of status”) that ultimately coalesced around a small set of themes, notably the specific sociocratic practices, benefits of these practices and the challenges experienced in their implementation. Additionally, he identified some connections among some of the analytic categories that spanned the different elements, notably when it came to the four types of inequality that helped explain some of the challenges experienced, as all of them dealt with some form of unevenness among members of the community. Daniel had not been to PCH but has worked alongside many sociocratic organizations, and also has a background in nonprofit studies. He was able to evaluate the data from an expert outsider perspective, enabling a further ‘de-naturalization’ and challenging of the interpretations of Martyn. In line with the practices of the group we studied, we used consent regarding our interpretations. The results of this analysis now follow.

Case Study: Phoenix Co-Housing

Aspirations and Apprehensions of Sociocracy

Phoenix Co-Housing is a co-housing community intended for elderly retired individuals. Indeed, Dorothy (a member of the co-housing community, who, as are all other names that follow, has been given a pseudonym) suggests PCH is a nonprofit that aspired to combat the loneliness and vulnerability of old age:

I just thought that when people get older, in this country, they become isolated and often depressed and lonely, and if we lived in a tight knit community, a little village, where we all knew each other, we could prevent that isolation and loneliness and also, we could protect each other.

From inception, it was recognized that the project needed to integrate inclusive decision-making processes while ensuring the project made swift progress:

We made every decision. We chose our bank. We chose our contractor. We did all our own marketing. We did all our own membership. We did everything…[t]here were a million decisions to be made. We needed a model that would allow us to do that.

The residents, therefore, searched for an appropriate democratic model. However, given their own extensive individual histories with organizing, they were aware of the potential shortcomings of a collective, participatory approach, such as potentially slow decision-making (Reedy et al., 2016). Eventually, the founding residents were encouraged to choose sociocracy as their democratic governance model as an advisory consultant had highlighted the growing popularity and potential of sociocracy within the co-housing sector. It was suggested that sociocracy—driven by consent rather than consensus—could ensure everyone had a voice in the process while still managing to ensure decisions got made. According to Dorothy, this was a large attraction of this specific model:

It was a model for the whole organization, where power was transferred to everyone and everyone had a voice at the table, thus problems could have the best solutions because with everyone having a say, [the community] were bound to get better solutions than if just one or two people were making the decisions.

However, nobody within the community had direct experience of using sociocracy and from the outset there were apprehensions about adopting it as a decision-making model. Sylvia, for instance, expressed that the “initial meetings were so hard” while others described the meetings as “scary” (Janet) and even “a little bit tedious” (Billie) requiring residents to slowly learn the minutiae of a highly regulated process of decision-making. There was resistance, for this reason, even from the outset. As Billie explained: “a few people don’t want a two-day workshop [to learn sociocracy]. I’m for any kind of adult learning, I’m 100% on it, but some people don’t want to sit for two days and learn.” This even went as far as leading a small minority to leave the housing community:

Somebody came to my house and said, we’re putting our house up for sale, we’re leaving after that meeting. So, this is a person that has never taken advantage of lessons on sociocracy, any conversations on sociocracy, just isn’t willing to learn it and play along. (Carole)

In what follows, we provide a critical exploration of the key elements of sociocracy (as outlined above) in the context of PCH. We consider what made it so attractive in this NPO while also attempting to understand challenges experienced during the implementation, which led to pockets of resistance. We then discuss how four forms of inequality contributed to these challenges.

Circular Hierarchy with Clear Domains

In order to make decisions democratically at PCH, it was decided that residents “would break down into smaller circles and then have the right to make decisions within their domain” (Jim). As Terry suggested, to get PCH established “Membership [circle] and marketing [circle] had to work together and finance [circle] and legal [circle] to make a lot of decisions. In order to build [the community], we had to have a construction interface [circle] and that was made up of five people…and we used sociocracy to nominate them. They went between the professionals [builders, architects, etc.] and the general membership because we couldn’t have 40 people telling people what to do.” We provide an overview of PCH’s structure in Fig. 3.

Importantly, the domain of these circles focused on policy formation to enable the circle to achieve its purpose. Dorothy, for instance, spoke about the neighborhood [circle]:

one of the hard things about doing a project like this is—this was a beautiful valley filled with animals, deer and wildlife and so the people around didn’t want the valley developed. So…we had a neighborhood [circle] who contacted every single neighbor and said we wanted to be good neighbors. We were community members and we did a lot of public relations

There were some clear immediate benefits of adopting circular hierarchy. As Dorothy explained: “I think it’s really good that the [circles] have the ultimate decision—it distributes the power out from the center, and I just think it’s healthy.” In his diary, Martyn also noted that “individuals seem to be proud of their membership of specific circles” suggesting that members “feel empowered, primarily because they can make decisions about what they care about most while letting others get on with doing the same elsewhere”. Sociocracy, therefore, harnessed the dual benefits of democratizing decision-making to members, while also delegating accountability to the circles ensuring that a faster process was achieved than in a traditional flatter democratic organization where members are expected to be involved in every key decision. Nevertheless, the shift toward sociocracy was not without problems. One member, talking about one of the external trainers who helped PCH to adopt circular hierarchy suggested “he threw a hand-grenade into the door then he left” (Billie), alluding to “throwing” a new and highly complex form of decision-making at the residents and then leaving the community to deal with the consequences. One of the main problems, according to Dorothy, is that “we’re still struggling because some people want to make decisions about everything” and as Caroline suggests “there can be a little bit of fear and a little bit of anxiety over letting go.”

The Use of Consent

The implementation of consent as a mode decision-making within PCH was a very attractive principle to virtually all members. Everyone needed to be taken seriously. As one resident of PCH, Sylvia, suggested: “49% of your group unsatisfied…that was unfathomable. We couldn’t build a community doing that. So, we needed consent.” As Jim also explains, “the idea of consent, the idea that everybody needed to not say it was what they wanted but that they had tolerance for it, that you could live with them, yeah. And I wondered if that would work and it really has.” Terry concurs, stating, “we did rounds. Everybody had buy-in to consider this. If there was a discussion, this idea of range of tolerance always came in to play, so once people got on board with the idea of that, that’s what decisions were about. People were much happier.” This model of decision-making, in which a clear consent-based process requires active members to positively enable a decision, clearly has the potential to reduce abuses of power within and outside of the organization as it provides a relatively safe space to challenge wrongdoing and even stop it from emerging at all. As Martyn’s diary entry reflected during a circle meeting on his first day within PCH, “people shared views one by one, without cross talk, freely and openly without fears of reprisal or being undermined”. There was a real sense of undominated, uncoerced collective decision-making within the community.

The use of consent, however, did lead to tensions emerging within PCH around the needs of the individual and the needs of the collective. The problem was encapsulated by Stevie: “We didn’t know what to do when someone said they had an overriding objection and nobody else agreed with them, but they were still sitting there with this objection. It was like, now what do we do?” While visiting PCH Martyn noted that there were various “heated, and highly charged deliberations” around, for instance, a couple wishing to park a larger van on the site and a couple wishing to change the “look” of the outside of their house, which directly contravened the will of the collective. And indeed, these disagreements had become so impossible to work through that individuals were threatening to leave the community. As Carole suggested, though, there was an expectation that these types of disagreement would continue to emerge and were a part of the system: “I think there’s always going to be that tension between what the individual wants and what the whole group wants. I can’t imagine that ever going away.”

Double-Linking

The implementation of double-linking at PCH was possibly the most complex aspect of sociocracy to introduce and integrate into members’ everyday activities. Billie explained it as follows: “double-linking is when each circle has two members that go [to circle A], one represents their own [circle B], and the other one represents the [general circle], and then they listen to what’s going on [in circle A], and they take it back to the team. Yeah, one person sends it down [to circle B] and the other person sends it up [to the general circle], and I don’t think we understand that. It’s not always happening.” And yet, many members did recognize the value in pursuing its implementation. One PCH resident, John, explained that “sometimes [failing to learn and remember] is the best lesson: “do you remember the day that we were talking about X?” [laughs] and nobody remembers—okay, that’s why you need double-linking.” Additionally, Martyn’s field diary suggested that “where it is taking place, double linking is enabling the flow of learning to occur between circles, encouraging learning and preserving organizational memory—but this process is anything but consistent”. Indeed, there was a feeling by some that double linking (and the associated learning that goes with it) was not taking place. One core reason for this was double-linking requires people to attend more meetings (sometimes on issues that they are less centrally concerned about) and that, as Billie suggested, “nobody is policing—we have no police officer here” to make sure that the “correct rules” are being implemented.

Practices to Foster Inclusivity and Voice

PCH had several practices in place to foster inclusiveness and voice, including rounds, rules about meeting conduct, and facilitator roles. In doing so, it attempted to secure equivalence and inclusiveness in the housing community and this was, in part for many members, entirely achieved. Martyn witnessed multiple circle meetings in which “participants calmly waited in a large circle for their turn to speak, without cross talking or interruptions”. This created a safe space for individuals to know that they would be listened to and heard in a way that they often were not used to. For instance, Ann suggested “I was astounded, not only by the egalitarian process of how everybody listened to each other [but also how they] were able to express their views and how everybody was heard”. Other residents such as Carole described “the respect that is garnished by waiting for others to speak”.

However, interviewees also highlighted how, despite everyone having the opportunity to participate in equal terms, not all of them took this opportunity. As Carole suggests: “I think one of the negative aspects would be that even though everyone has a chance to talk and we encourage that, not everybody does. I don’t think they’re able to come up with their thoughts quickly enough and it’s like—oh the next day, it’s like, I should have said this and the other thing. If they’re not willing to participate fully, then you don’t get the full effect of how great it could be really.”

Inequalities as Contributors to Challenges Experienced

Through our analysis, we identified four types of inequality that helped explain several of the challenges we identified with the implementation of the four abovementioned elements of sociocracy. While each of these was identified for a specific element, upon further reflection we realized that all of them were relevant to better understanding the other challenges that spanned the other elements.

The first was an inequality of status—unevenness in relative social standing—in the new circular hierarchy. All members are considered equal but some have carried over behavior from hierarchical systems that they previously worked within. One member, Billie, calls these individuals “control freaks” and describes another member who involves herself in “pretty much everything… She pretty much keeps her finger in every pie. Which, it can be good, but it also can be negative for the whole group.” This reflects a tendency to drift or bleed back toward old hierarchical power structures, and this would be particularly tempting within NPOs as they regularly change membership, and teaching new ways of decision-making might be seen as more difficult than reverting to more familiar ways (Diefenbach & Sillince, 2011). Dorothy calls this ‘governance drift’ in which she warns that those using sociocracy “have to be vigilant about continuing the training and demonstrating and modeling and getting the principles out there, and trying to shore up problems that—clarity, clarity, clarity about things. Any time you have a problem in governance, if you have a good system, it’s a system that solves the problem.”

Other members highlight how this form of inequality might stem from how long individuals and couples have been within the community. Millie suggests: “I think there is perception that there are those of us who were so engaged in the building process and some of them were from the get-go. Their opinions have more weight, and not necessarily should they be given more weight…I think that’s very harmful.” This reflects the common experience of “founder’s syndrome” in which those who started the organization are considered more knowledgeable and important within the organization. As Jane explained at PCH, “since those initial [founder] people have been there in those jobs [roles within circles], carrying those functions for so long, there is some resentment. Some people feel they’re not in as deeply as others might be. Some folks have the vocabulary of a higher circle. It leads to different steps and levels.” This is often unwanted by the founder(s) but persists as staff members find themselves putting more weight in this historically important figurehead. Other founders may simply find it more tempting to embrace the inequality for what they consider to be the productive good of the organization.

The second was an inequality of expectations, an unevenness in assumptions and beliefs about requirements for the democratic governance model to function effectively. In a sociocratic model of governance, there are fewer ways of exploiting the rules than in a less formally regulated model of decision-making, where short cuts can usually be found by individuals to get what they want by force. Sociocracy can therefore be highly frustrating for some members who are used to pursuing this way of getting things done in an organizational context.

The third was an inequality of application, an unevenness in how the rules and procedures of the democratic governance model are operationalized. For instance, Martyn, in his diary, reflected that “it seems odd that different circles choose to operate quite strictly adopting all the rules of sociocracy while others are much more laid back, not choosing to apply things like double linking”. Referring to her difficult experiences with her circle not properly implementing double linking Carole somewhat frustratedly explained: “I was 12 months ahead of everybody, and I just quit the team, because I was too frustrated to stay with them.” This meant that there was a persistent feeling of inequality in terms of how different circles were being asked to operate and how different individuals were being asked to adhere to rules within the wide dynamic governance system.

Finally, the fourth was an inequality of capacities, an unevenness in abilities to take part within and contribute to the democratic governance model. Some participants were quite open about their inability to be patient within the circle and display emotional intelligence: “I have absolutely no skill to deal, especially when someone is wrong. I have no skill…I dropped out of two meetings because I just don’t know how to deal with it. I have no skills. I grew up an only child. I had half-brothers, but I grew up an only child. Then my personality, I’m semi-introverted” (Billie).

In addition this, there is also the parallel unwillingness of some members to take on new powers within the demanding sociocratic system (see King & Land, 2018). This points toward an inequality of capacity in terms of time and energy to apply to a demanding democratic governance system. Carole explained: “it really bothers me that there’s three or four people that don’t do anything. They don’t join us at meals, they don’t work on any teams, they’re not ill. I don’t know what the hell they’re doing in their house but come on. I think the whole community would like to see those people come out.” This sets up an inequality in how much people are willing to give and include themselves in what is a system that requires a lot of work to make it operate successfully.

There was also an understanding that while inclusivity was a core value of PCH (and a key reason for the adoption of sociocracy), those individuals who knew the rules best were able to manipulate them to get what they wanted. One member Sylvia described another woman in the group as follows: “she’s the real powerhouse and [pause] she’s so—competent that it’s sort of hard to ignore anything she may say.” Sylvia went on to explain the centrality of inequality arising at PCH as follows: “there are other people who say, ‘It’s got to be this way, it’s got to be this way’ and they are the ones who need to tone back a little bit and listen more and accept the decision of the group. And I think that it’s for the most part happening. I mean the stronger people obviously still have more power of persuasion.” While these types of organizations go to great lengths to provide equity of voice, then, there are inevitably situations in which certain individuals may have more influence than others—it seems to be more an issue of how the organization broaches these persistent inequalities.

Discussion and Conclusion

Engendering democracy in NPOs is no easy feat. This paper, motivated by calls for deeper understandings of how different organizational forms can influence democratic outcomes (Lee, 2022), has explored one of these alternative forms of NPO governance in practice (Renz et al., 2022). Specifically, we examined the potential for sociocracy to enhance NPOs governance through undertaking a case study of PCH, an NPO that has adopted sociocracy.

Our primary contribution focuses on the possibilities (and limitations) of sociocracy to improve democratic governance within NPOs, particularly its role in fostering inclusion. This builds on a notable recent increased attention on the democratic potential and limitations of contemporary approaches to governance (Guo et al., 2014; Torpe, 2003; Van Puyvelde et al., 2016), and a rising interest in alternative forms of governance. As a result, sociocracy has emerged as a promising form of democratic governance, warranting further research into its potential (King & Griffin, 2019; Renz et al., 2022). Our exploratory study advances our understanding of how four central elements of sociocracy can help decentralize opportunities for member participation in an effective manner; reduce the risk of domination and coercion by a subset of members and, in turn, empower more members contribute to discussions and bring their perspectives to bear on decision-making; and facilitate organizational learning. The use of a circular hierarchy decentralizes decision-making and empowers members to participate in democratic decision-making. The use of consent and practices to foster inclusiveness and voice help ensure that members feel comfortable sharing their perspectives, brings a broader array of perspectives to decision-making, and reduces the risks of domination and coercion that sometimes accompany democratic governance. Double-linking helps improve the flow of information through an organization, facilitating organizational learning. Finally, practices to foster inclusivity and voice improve listening and foster mutual respect.

In doing so, sociocracy provides a way to begin to challenge the slowness of horizontal decision-making (Reedy et al., 2016), and find ways of increasing participation (Van der Meer & van Ingen, 2009) and influence (Torpe, 2003) of members through the use of circles and domains. By studying and implementing alternative forms of democratic governance, our paper provides researchers and practitioners with a set of core elements of sociocracy that can inform future theoretical and applied work.

However, our critical approach also suggests—somewhat paradoxically given the emphasis sociocracy places on inclusiveness—that implementing sociocracy can also bring inequalities to the surface in unexpected ways. We identified four main forms of inequality, those associated with status, expectations, application, and capacities. Our analysis points to how each of these inequalities can have negative consequences for NPOs, including diminishing the individual and organizational benefits of sociocracy and risking the gradual drift away from specific practices in some or all parts of the organization. Thus, even within more structured organizational forms like sociocracy, longstanding issues of the illusion of equality that have traditionally beset more informal democratic organizations (Freeman, 1972), still persist. Awareness of these unintended consequences are important for NPOs to take account of and to search for solutions to in their capacity as “schools of democracy” (Dodge & Ospina, 2016). In short, they should not treat sociocracy as a readymade solution, but as a way of working through the dynamics of participation in a collective way (Griffin et al., 2022). While we identified them in the context of NPOs, they are likely to be applicable to a broader array of organizational contexts, warranting further attention from advocates of sociocracy, who have tended to focus more on its potential benefits and contributions.

Therefore, governance alone cannot achieve inclusion. However, by identifying these four potential types of inequalities, we hope that this paper can support practitioners to confront and work through them. Through creating an awareness of, and thus surfacing these inequalities, we argue that this case study provides the possibilities for practitioners within NPOs to be able to discuss, and work through them. The tools of sociocracy, particularly those of feedback sessions (Rau & Koch-Gonzalez, 2018), provide opportunities for reflective spaces where these types of inequalities can be raised, and in a dialogical way, worked through. We do not suggest that this will automatically eliminate these inequalities, but rather provide resources to work through them.

At the same time, this paper has important limitations that set the stage for future research. First, while our case study provided us with a detailed understanding of PCH’s members’ experience of sociocracy, we cannot generalize our findings to all NPOs. PCH is a relatively small organization, with a specific aim of developing a community, and is thus quite different in form and structure to many NPOs, which might have, for instance, status differences between paid staff and volunteers. Implementation might vary due to history, size, location, economic orientation or previous organizational governance. Future research could explore how different factors impact implementation, ideally through a comparative case methodology. Second, we gathered data primarily in one period. While this enabled us to get rich insights about the current implementation, a more longitudinal design would help unpack how the constellation of benefits and challenges evolves (Renz et al., 2022). Third, given the dearth of empirical research on sociocracy in NPOs, our study was exploratory. Further research is needed to validate and build on our analysis, investigating topics like the interdependencies among different elements of sociocracy and how they influence the benefits and unintended consequences we identified.

References

Boeke, K. (2007). Sociocracy: Democracy as It Might Be. In J. Buck & S. Villines (Eds.), We the people: Consenting to a deeper demoracy, a guide to sociocratic principles and methods (pp. 191–199). Sociocracy.info.

Buck, J., & Villines, S. (2007). We the people: Consenting to a deeper democracy, a guide to sociocratic principles and methods. Sociocracy. Info Press. ISBN

de Tocqueville A. ([1840]2003). Democracy in America. London: Penguin Books.

Dekker, P. (2019). From pillarized active membership to populist active citizenship: The Dutch do democracy. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 30(1), 74–85.

Diefenbach, T. (2019). Why Michels’ ‘iron law of oligarchy’ is not an iron law: And how democratic organisations can stay ‘oligarchy-free.’ Organization Studies, 40(4), 545–562.

Diefenbach, T., & Sillince, J. A. (2011). Formal and informal hierarchy in different types of organization. Organization Studies, 32(11), 1515–1537.

Dodge, J., & Ospina, S. M. (2016). Nonprofits as “Schools of Democracy” A comparative case study of two environmental organizations. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 45(3), 478–499.

Eikenberry, A. M. (2009). Refusing the market: A democratic discourse for voluntary and nonprofit organizations. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 38(4), 582–596.

Endenburg (2023). (Almost) a century of Endenburg. https://endenburg.nl/over-ons/onze-geschiedenis/

Enjolras, B. (2009). A governance-structure approach to voluntary organizations. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 38(5), 761–783.

Freeman J. (1972). The tyranny of structurelessness. Berkeley Journal of Sociology. 151–164.

Griffin, M., King, D., & Reedy, P. (2022). Learning to “Live the Paradox” in a democratic organization: a deliberative approach to paradoxical mindsets. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 21(4), 624–647.

Guo, C., Metelsky, B. A., & Bradshaw, P. (2014). Out of the shadows: Nonprofit governance research from democratic and critical perspectives. In C. Cornforth & W. A. Brown (Eds.), Nonprofit Governance: Innovative perspectives and approaches (pp. 47–67). Routledge.

King, D., & Griffin, M. (2019). Nonprofits as schools for democracy: The justifications for organizational democracy within nonprofit organizations. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 48(5), 910–930.

King, D., & Land, C. (2018). The democratic rejection of democracy: Performative failure and the limits of critical performativity in an organizational change project. Human Relations, 71(11), 1535–1557.

Kokkinidis, G. (2015). Spaces of possibilities: Workers’ self-management in Greece. Organization, 22(6), 847–871.

Leach, D. K. (2016). When freedom is not an endless meeting: A new look at efficiency in consensus-based decision making. The Sociological Quarterly, 57(1), 36–70.

Lee, C. (2022). Which voluntary organizations function as schools of democracy? Civic engagement in voluntary organizations and political participation. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 33, 242–255.

Locke, K., Feldman, M., & Golden-Biddle, K. (2022). Coding practices and iterativity: Beyond templates for analyzing qualitative data. Organizational Research Methods, 25(2), 262–284.

Maeckelbergh, M. (2012). Horizontal democracy now: From alterglobalization to occupation. Interface, 4(1), 207–234.

Pateman, C. (1970). Participation and democratic theory. Cambridge University Press.

Rau, T. J., & Koch-Gonzalez, J. (2018). Many voices one song: shared power with sociocracy. Sociocracy For All.

Reedy, P., King, D., & Coupland, C. (2016). Organizing for individuation: Alternative organizing, politics and new identities. Organization Studies, 37(11), 1553–1573.

Renz, D. O., Brown, W. A., & Andersson, F. O. (2022). The evolution of nonprofit governance research: Reflections, insights, and next steps. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 52(1_Suppl), 241S-277S.

Romme, A. G. L. (1995). The sociocratic model of organizing. Strategic Change, 4(4), 209–215.

Romme, A. G. L. (1999). Domination, self-determination and circular organizing. Organization Studies, 20(5), 801–832.

Spear, R. (2004). Governance in democratic member-based organisations. Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics, 75(1), 33–60.

Torpe, L. (2003). Democracy and associations in Denmark: Changing relationships between individuals and associations? Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 32(3), 329–343.

Van der Meer, T. W., & van Ingen, E. J. (2009). Schools of democracy? Disentangling the relationship between civic participation and political action in 17 European countries. European Journal of Political Research, 48(2), 281–308.

Van Puyvelde, S., Cornforth, C., Dansac, C., et al. (2016). Governance, boards, and internal structures of associations. The Palgrave handbook of volunteering, civic participation, and nonprofit associations (pp. 94–914). Springer.

Verba, S., Schlozman, K. L., & Brady, H. E. (1995). Voice and equality: Civic voluntarism in American politics. Harvard University Press.

Yin, R. (2014). Case study research: Design and methods. Sage.

Funding

Funding was provided by Economic and Social Research Council (Grant No. ES/N001559/1).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

There is no conflict of interest.

Human or Animal Participants

The research involved human participation.

Informed Consent

All participants fully consented to the research.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

King, D., Griffin, M. Governing for the Common Good: The Possibilities of Sociocracy in Nonprofit Organizations. Voluntas (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-023-00627-2

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-023-00627-2