Abstract

Philanthropy seeks to address deep-rooted social issues and assume responsibility for the creation of public goods not provided by the public sector—and in this way help reduce inequality. Yet philanthropy has also been criticized for bypassing democratic mechanisms for the public determination of how to invest in society—and thus may perpetuate other inequities. In both cases, inequality, defined as asymmetries of resources and power, plays a critical role in public goods creation and in the legitimacy of a country’s philanthropic ecosystem. However, little empirical research examines the existence and role of inequality in country-level donation systems. To fill this gap, this study provides evidence of growing donation concentration in Chile’s philanthropic ecosystem, with a focus on the culture sector, characterizes it by mapping systematic differences in ecosystem perceptions by actor type, and identifies and tests statistically structural and organizational factors associated with these perceptions. Inequality in Chile’s donation system operates at multiple geographical, legal, and organizational levels, all of which are reflected in objective donation amounts and subjective ecosystem perceptions. We conclude that in Chile resource asymmetries and power imbalances hinder the fulfillment of philanthropy’s promise and call for further research to identify policies that address inequities in emerging philanthropic ecosystems in Chile, Latin America, and beyond.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

A central paradox in contemporary philanthropy is that its existence is symptomatic of the social problems—mainly poverty and wealth inequality—it seeks to address. This contradiction has been present since the birth of modern philanthropy in the nineteenth century. Andrew Carnegie argued that to address wealth inequality the rich should administer responsibly and with “intense individualism” accumulated resources in order “to help those who will help themselves” (Carnegie, 1889[1901]). Oscar Wilde retorted that although philanthropists acted “with admirable, though misdirected intentions … their remedies are part of the disease” (Wilde, 1891[1969]). Instead, the goal is to reconstruct society in order to eliminate poverty and inequality, thus eliminating the need for philanthropy. Regardless, Carnegie and Wilde were aligned in that both recognized the underlying tension between inequality and philanthropy. Rather, they diagnosed different causes and remedies.

Over a century later, wealth inequality not only remains a symptom of the disease philanthropists seek to cure—it has assumed new dimensions. On one hand, philanthropy is touted as critical to foster solutions to deep-rooted social issues and complement or even take responsibility for public goods not created by the state—and in this way reduce poverty and inequality (Singer, 2009). On the other hand, inequality within the philanthropic ecosystem may distort the giving sector and delegitimize philanthropic endeavors (Reich et al., 2016). Reliance on fewer and bigger donor sources can make civil society organizations (CSOs) more dependent on donors, which affects their sustainability (Collins & Flannery, 2022). Concentration can also limit dynamism and innovation in the sector (Pasic et al., 2020). Finally, since concentration gives large donors more influence in public goods creation, they may bypass democratic mechanisms for the public determination of social investment (Reich, 2018).

A general concern about the relationship between inequality and philanthropy permeates the literature (von Schnurbein et al., 2021). A keyword search for “inequality” and “philanthropy” in Voluntas returns over 100 empirical articles, with publications including critiques of philanthro-capitalism (Herro & Obeng-Odoom, 2019), examinations of giving pledge letters (Schmitz et al., 2021), overviews of corporate philanthropy in India (Godfrey et al., 2016), and micro-level analysis of Danish volunteer-recipient interactions (Bang Carlsen et al., 2020). Yet targeted examination of the nature and implications of inequality or, more specifically, resource and related power asymmetries within a country’s philanthropic ecosystem are scant.Footnote 1 This study seeks to fill this gap by studying the role inequality plays in Chile’s philanthropic ecosystem.

Latin America in general and Chile in particular offer an ideal site for examining philanthropic inequality. The region is home to the globe’s highest levels of wealth inequality (Mattes & Moreno, 2018). In the post-Cold War era, macroeconomic growth led the World Bank to reclassify most Latin American countries as middle-income in the first two decades of the twenty-first century, prompting a reduction of overseas development assistance (ODA) to the region (OECD, 2021). Governments were expected to fill the void. Despite this “inclusionary turn” (Kapiszewski et al., 2021), however, the persistence of weak state institutions and muted spending either by design or a lack of state capacity left gaps in coverage which the emerging local philanthropy sector has sought to fill (Berger et al., 2020; Bird & Leon, 2019).

Chile sits at the leading edge of this regional transition. Since the 1990s, the country’s social sector has exemplified Latin America’s evolution away from ODA to local private and public financing. As the second country in Latin America to join the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), Chile experienced high rates of market-driven growth leading the World Bank to reclassify it as high-income in 2013. Yet, like other Latin American countries, Chile registers high rates of inequality. One would expect the combination of muted public spending, economic growth, increasing wealth, and high inequality to create ideal conditions for the emergence of a dynamic philanthropic ecosystem. But like other countries in the region and globally, we lack evidence for understanding the role inequality plays in Chile’s philanthropic sector.

Two factors impede the study of philanthropic inequality. First, while critiques highlight possible influences of inequality in the ecosystem, we still do not have a theoretical framework to guide empirical research. Second, macro-level studies of ecosystems require country-level data from administrative or primary sources. National reporting systems, especially globally, either lack the data or limit public access, while country-level surveys are challenging because of cost and, in many cases, the inexistence of an established sampling frame of donors and recipients.

This study tackles these obstacles and helps fill a regional and global research gap. Since little theoretical work circumscribes the problem of inequality and related asymmetries in the philanthropic ecosystem, we borrow from economics and organizational sociology to offer an initial framework to guide the study and specify three research questions. Next, we respond to these questions, with each building on results of the former: (a) is there inequality in Chile’s donation ecosystem? (b) what characterizes it? and (c) what factors are associated with this characterization?

To respond to the first question, we use government administrative data to assess the level of donor and recipient concentration. In doing so, we establish evidence for the existence of philanthropic inequality in Chile, which provides a basis for responding to the subsequent questions. The second question enables a “subjective” characterization of ecosystem inequality by using an original national survey of 169 companies, 79 foundations, and 215 recipient civil society organizations (CSOs) to map, via a multiple correspondence analysis (MCA), systematic differences in ecosystem perceptions. Based on these results, we respond to the third question by generating exploratory hypotheses that either explain or establish associations with these perceptions and then test them via regression analysis.

Results indicate that inequality in Chile’s philanthropic ecosystem is reflected in the increasing concentration of donations (question 1) and subjective ecosystem perceptions (question 2), with the latter associated with specific structural and organizational factors (question 3). We conclude with discussion of implications and directions for future research, especially in Latin America.

Inequality in Philanthropy

An examination of inequality among and between philanthropic actors—be they individual donors or grant-making foundations, nonprofit organizations or voluntary associations, governments or multilateral bodies, beneficiaries or citizens—requires a guiding framework for conceptualizing the agents involved, their relationships, and the flow of material and symbolic resources. Such a framework helps to specify the nature of inequality between actors and identify implications for the optimal functioning of the philanthropic sector, however defined.

But no such framework exists. Rather, there are disparate critiques of the role of inequality and its consequences for the functioning of philanthropy. To guide our study, we present an initial framework which systematizes three major critiques of inequality in philanthropic ecosystems. As we introduce these critiques, we connect them to existing theoretical approaches in economics and organizational sociology before highlighting their implications for Latin America and, in particular, Chile.

Critique 1: Donor Concentration Makes Nonprofits More Dependent and Less Sustainable

Theoretically, donor concentration may come in one of two forms: (i) less total number of donors or (ii) an increasing share of total donation amounts controlled by fewer donors. While the paucity of country-level data on philanthropic ecosystems makes it difficult to establish empirical levels of donor concentration, two countries for which system-wide information is available reflect how concentration has increased in each, especially since the 2008 global financial crisis.

Since 2016, the Institute for Policy Study’s “Gilding Giving” reports have highlighted a series of risks associated with the concentration of philanthropic giving in the USA (Collins & Flannery, 2022). While in 1993 the top 1% of the country’s income earners accounted for one-tenth of charitable deductions, by 2019, this share had risen to two-thirds. Between 2008 and 2018, the percentage of all households giving to charities fell from 65 to 50%. During this same period, the amount of assets held by private US foundations doubled to over US$ 1 trillion. The Mexican philanthropic ecosystem also exhibits evidence of donor concentration (Villar & Puig, 2022). In 2020, 3% of authorized grant-making organizations were responsible for 81% of total donations. Meanwhile, 6% of donor recipient organizations captured 36% of total donation amounts, while 51% account for 20% of total donation amounts.

The microeconomics discipline has long theorized and codified the dynamics created by the concentration of suppliers (e.g., monopoly, duopoly, oligopoly) or buyers (e.g., monopsony) and how they create power and negotiation imbalances between actors, with consequences for optimal market functioning (Nicholson & Snyder, 2007). In the case of philanthropy, regardless of whether one construes donors as suppliers (i.e., providers of social investment capital) or buyers (i.e., purchasers of the private production of public goods and their expected social impact), the existence of ever larger donors implies more leverage over recipient organizations. For recipients (i.e., charitable organizations), concentration could also increase competition for donor funds, inserting unpredictability into nonprofit planning and budgeting. To secure financing, nonprofits may become more likely to sacrifice their strategic goals to serve donor objectives.Footnote 2

From an organizational sociology perspective, the effects of concentration or competition for donor funds has been examined for nonprofits via a resource dependence perspective (Pfeffer & Salancik, 1978). This framework generates predictions about what types of organizational forms and decisions emerge given the nature of resource dependence. For example, board structures serve as a hedge to span operational, functional, or domain-specific boundaries and secure resources (Callen et al., 2010). The degree of nonprofit dependence may also spur more compliance with financial reporting regulation (Verbruggen et al., 2011) and acceptance of higher auditing fees (Verbruggen et al., 2015). Revenue diversification responses, which help decrease financial volatility, have also been related to improved nonprofit survival (Carroll & Stater, 2008) and performance (Kim, 2017). Despite arguments that nonprofit revenue concentration may lead to improved efficiency (Frumkin & Keating, 2011), a direct test comparing revenue diversification with revenue concentration strategies lends support for the stabilizing effects of revenue diversification.

For this study, we define inequality from the economics and resource dependency perspectives. It is the lack of or difference in access to philanthropic resources resulting from concentration of capital in the “donor market” (microeconomics), which manifests as power imbalances between actors in the philanthropic ecosystem (resource dependency). This definition provides a frame for establishing the existence of inequality in the Chilean philanthropic ecosystem (question 1).

Insights from the resource dependence framework suggest that in Latin America the reduction in ODA and increasing reliance on public funding and private donors may generate financial volatility for CSOs in general, especially local nonprofits (Appe, 2018; Appe & Pallas, 2018; OECD, 2021), creating what may be considered a “middle-income social investment trap” (Bird & Leon, 2019) On one hand, the reduction of ODA could give CSOs more autonomy from the conditions set by foreign donors. On the other hand, the autonomy obtained depends on the nature of any new power imbalances with local private donors and public funding. Depending on the country, public funds may also play an important financing role (Berger et al., 2020), as in Chile (Aninat & Fuenzalida, 2017), Colombia (Villar, 2018), and, until recently, Mexico (Villar & Puig, 2022). In these situations, organizations risk developing dual but competing dependence on private donors and public funds, with each requiring different reporting requirements. In the face of inequality, we expect, in this study, to detect consequences of donor concentration and related power asymmetries in different actors’ perceptions (question 2) and in structural and organizational factors related to these perceptions (question 3).

However, donor concentration and related power asymmetries may have at least two other major consequences for the functioning of philanthropic ecosystems.

Critique 2: Donor Concentration Results in Less Actors, Limiting Dynamism and Innovation

The concentration of donor resources may limit dynamism and innovation (Pasic et al., 2020; Reich, 2018). This is critical since one of the potential attributes of civil society, especially in Latin America, is its ability to identify emerging social challenges and contribute innovative solutions (Pozzebon et al., 2021; Sanborn & Portocarrero, 2005).

The “fields” concept used in organizational ecology (Hannan & Freeman, 1989) and new institutionalism (Scott, 2013) helps to examine the nature of nonprofit dynamism. Extending this concept to philanthropy, the ecosystem “field” consists of donors (governments, companies, foundations, and individuals), recipients (CSOs, including nonprofit organizations and voluntary associations), and the regulatory and institutional framework (regulative, normative, and cultural). The population of organizations may change over time given distinct “ecological” pressures, such as the reduction of ODA. In such a framework, resource dependence and power imbalances within philanthropy’s organizational field could limit the dynamism, risk-taking, and exploration necessary for social innovation.

For example, to compete for scarce donor resources, nonprofits may subject themselves to a process of institutional isomorphism (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983), as seen with nonprofits in Australia (Leiter, 2005, , 2013) and China (Kang, 2019). In particular, donor concentration may make nonprofits more vulnerable to “coercive” isomorphism or organizational copying in response to donor demands. To secure funds, CSOs may be more willing to adapt their organizations to fulfill donor objectives, which in turn may force them to sacrifice their missions and minimize organizational diversity critical for fostering sector dynamism and innovation.

A country-level analysis of donor concentration and power imbalances would thus focus on the organizational population dynamics in the philanthropic sector to assess to what extent the number of CSOs increases or decreases, while evaluating the degree of similarity among CSOs and its relation to the number of active donors in the sector. An organizational fields perspective sensitive to the role of resource inequality and power asymmetry within the philanthropic ecosystem may also help advance nascent research on the sustainability of nonprofits and other CSOs in Latin America (Fifka et al., 2016).

This study operationalizes the organizational fields concept to map actor perceptions of the ecosystem’s legal, tax incentive, public valuing, and cooperation components (question 2). Our results highlight the differential pressures of resource inequality and power asymmetry in the ecosystem (question 3).

Critique 3: Large Donors Influencing Public Goods Creation Risk Democratic Legitimacy

Finally, donor concentration may give large funders undue influence in public goods creation. This is problematic because of the risk of bypassing democratic mechanisms for the public determination of resource allocation for public goods (Reich et al., 2016). The power and influence exercised by large donors may thus lack accountability. Instead, policies could seek to create the conditions for the philanthropic ecosystem to serve as a decentralizing force and incubator for innovation (Reich, 2018), as opposed to spurring isomorphism as discussed previously.

The risk of losing political legitimacy is critical in Latin America, given the region’s history of right- and left-leaning authoritarian regimes, existing wealth inequality, and low levels of political and institutional trust (Mattes & Moreno, 2018). The health of the region’s democratic institutions depends on the vibrancy of its civil society. The undue influence of private donors or a lack of political and community legitimization could undermine the role of nonprofit and voluntary associations. However, we lack evidence for determining (i) to what extent inequality in the philanthropic ecosystem exists objectively or subjectively, especially in Latin America (questions 1 and 2), and (ii) whether this inequality (i.e., donor concentration and related power asymmetries) affects public goods creation (question 3).

In sum, the concepts of donor concentration, resource dependence, organizational fields, and political legitimacy provide a vocabulary to better understand inequality within Chile’s philanthropy sector. This framework also serves as an initial guide for operationalizing and characterizing the nature and consequences of inequality within a philanthropic ecosystem. Donor concentration may not only harm donor legitimacy, but could also make CSOs more dependent, less sustainable, less dynamic, and less innovative. Is there evidence of donor concentration in Chile? If so, what are its characteristics and implications? And what factors help explain the level of observed (objective) and experienced (subjective) inequality in the country’s philanthropic donation system?

Question 1: Is there inequality in Chilean philanthropy?

Chile’s social sector transformation began during the transition from a military regime, culminating in general elections in 1989 (Irarrázaval et al., 2006). Democratization reestablished new development aid relationships since many international funders suspended support in the 1970s and 1980s because of human rights concerns (Calleja & Prizzon, 2019). By 2018, sustained macroeconomic growth and democratic stability enabled Chile to graduate from the list of countries eligible for ODA. The evolution of Chile’s social sector since 1990 exemplifies the transition in Latin America from ODA to local private and public financing, with other countries in the region following Chile’s path (e.g., Leon & Bird, 2018).

The number of CSOs in Chile grew a 100-fold from less than 3000 in 1989 to nearly 300,000 formalized legal entities in 2019 (Irarrázaval & Streeter, 2020). Funding initially came from a large influx of ODA in the early 1990s, reaching a peak of US$ 500 million per year. Yet once Chile was reclassified as an upper-middle-income country in 1993, ODA fell until it reached USD$ 100 million per year by 2000, with multilateral entities coming to increase its share of ODA over that of bilateral parties (Calleja & Prizzon, 2019). Parallel to the influx of foreign aid in the 1990s was a shift in how assistance was distributed. Whereas ODA during the military regime was given directly to CSOs, upon democratization foreign entities allocated funds to the public sector, through which resources passed to nonprofits. In the mid-2000s, the government was responsible for nearly half of nonprofit financing (Irarrázaval et al., 2006).

With the reduction in ODA and rise in local financing, the government developed a legal infrastructure to increase private giving. Between 1986 and 1993, legislation was introduced to incentivize donations for education and culture via tax deductions or credits (see Appendix 1). In the early 2000s, legislation further incentivized donations for poverty alleviation, disabilities, and other social ends, such as sports and community development.

However, this succession of legislation did not reflect a coordinated public policy. Rather, it arose organically in response to different issues in the public agenda. The resulting laws were uncoordinated in their conditions and obligations, generating legal uncertainty for participants, ex ante discrimination against different donor types, and inequitable conditions for CSO participation in the donation system (Villar et al., 2020).

In 2011, the government passed legislation that strengthened the right to create legal entities for the public interest, thus recognizing more fully the role of civil society and citizen participation in public affairs, a political vision shared by successive governments. However, parallel modifications of the legal financing infrastructure necessary to fund these new entities did not follow (Villar et al., 2020). This created a distorted and uneven system with differentiated incentives across thematic sectors, leaving some areas uncovered (e.g., environment and health care with high donation costs), while others benefited from donation incentives. This increased bureaucratic costs for donors and recipient CSOs. In other words, while legislation fostered CSO creation by reducing bureaucratic costs (demand), a parallel legal framework was not created to support financial sustainability, leaving CSOs to rely on an increasingly static and concentrated donor ecosystem (supply).

Methodology: Descriptive Statistics

To establish the degree of donor concentration in Chile, we used public government administrative data to track the evolution of total donation amounts in the ecosystem between 2009 and 2020. This period was selected for three reasons: (i) donation amounts increased markedly in the decade after the global financial crisis, (ii) legislation passed in 2011 contributed to an increase in the number of legal CSOs, and (iii) though uncoordinated, a series of tax incentives were created during this period to foster donations to specific sectors.

After examining general tendencies, we focus on the donation sector for which the government provides more detailed public information on philanthropic supply (donors) and demand (recipients)—the cultural sector. This sector also serves as a case of interest because of passage in 2014 of legislation seeking to strengthen the sector by expanding existing tax incentives for culture-related donations. We thus focus our analysis of the culture sector on 2015–2020. This sub-analysis provides a more detailed picture of the evolution of the demand (number of organizations requesting donations and amounts requested) and supply (number of organizations providing donations and amounts given) within one sector.

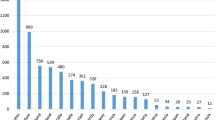

Results: Evidence of Donor Concentration

The decrease in direct international aid to CSOs, the increase in incentives for private donations, and lowered formalization costs for CSOs produced several effects in the philanthropy ecosystem. As seen in Fig. 1, donation amounts rose steadily between 2009 and 2014. But in 2015, total donation amounts abruptly plateaued and maintained the same absolute nominal level over the next five years.

Alongside this plateau in total donation amounts, recent studies show growth in the potential demand for donations, with a dramatic increase in the number of CSOs able to participate in the system. The legal form of foundations and nonprofit corporations (included in all laws with tax incentives for donations) doubled from 15,573 in 2015 to 31,022 in 2020, with 77% considered active (Centro Políticas Públicas UC, 2016 and 2020). Yet the number of recipient CSOs that effectively received donations decreased from 893 entities in 2015 to 793 in 2020, according to the national tax agency (Servicio de Impuestos Internos).Footnote 3 In other words, at a system-wide level between 2015 and 2020, the percentage of eligible CSOs effectively receiving donations fell, while average donations for those who received them increased.Footnote 4

A similar dynamic is seen in the culture sector, the only area for which there is publicly available data on the number of donors, number of recipient CSOs, requested donation amounts, and donations given. Table 1 highlights the tendency toward increasing donor concentration between 2015 and 2020, showing that fewer actors donated more to less organizations, while there remained high unsatisfied demand for donations from CSOs authorized to participate in the system. As with the system-wide figures, the culture sector highlights how less CSOs are receiving on average larger donations, except we can now visualize the concentration of supply: less donors are giving on average more per donor.

The evidence suggests the existence of a donor concentration dynamic outlined in the theoretical framework: more donor concentration (i.e., less donors controlling a greater percentage of total donation amounts) providing more funds to less CSOs.

Question 2: What Characterizes this Inequality?

Despite evidence of donor concentration, we lack understanding of its implications for operation of Chile’s philanthropic ecosystem both in terms of what characterizes this inequality (question 2) and the factors associated with it (question 3). To better characterize the inequality, we examine the differential perceptions of donors, foundations, and recipient CSOs toward aspects of Chilean philanthropy.

Methodology: Mapping the Ecosystem

Survey data were collected as part of the Primer Barómetro de Filantropía en Chile (Aninat & Vallespin, 2019). The initiative sought a holistic measurement of the emerging philanthropic ecosystem in Chile, including actor perceptions. These measures were used to operationalize an ecosystem index measuring the “health” of Chilean philanthropy (see Aninat & Vallespin, 2019 for details on the framework developed and supporting literature). The survey collected data between July and December 2018 from a representative sample of four actor types: companies, foundations, recipient CSOs, and citizens (see Table 2 for details), though this study examines only companies, foundations, and recipient CSOs.

The analysis focuses on four categories of variables, with each set consisting of a group of Likert-rated phrases. Categories captured included (a) understanding of the legal framework, (b) tax incentives, (c) valorization of the public’s appreciation of philanthropic activities, and (d) ease of cooperation within the sector (see Appendix 2 for original question items). These variables were used to conduct a multiple correspondence analysis (MCA) of the relationship between groups of actors and their responses. Our MCA used high/low dummy variables based on median cutoff points for the four ecosystem perception categories.Footnote 5 Once graphed, the MCA analysis is interpretive, with rules used to consider which variables should be taken into account for the interpretation.Footnote 6

Results: Mapping Actors’ Perceptions of the Ecosystem

The MCA results validate the “objective” findings of donor concentration with “subjective” or perceived power imbalances or asymmetries between ecosystem actors. Figure 2 depicts the model based on four high/low perception categories. Dimension 1 is the horizontal dimension, which accounts for 39.5% of the variance. Visually, one see responses fall cleanly upon a positive versus negative perception continuum. In other words, those who had low or negative perception of the philanthropic ecosystem in one perception category generally had a low or negative perception in the other categories. However, a vertical dimension also exists, representing 24.5% of the variance. In this case, the model detects a pattern whereby groups of organizations that have low or negative perceptions of society’s valorization of philanthropy also had a high or positive perception of the legal system, both in terms of understandability and incentives. The other end of the vertical axis indicates those organizations that had high or positive valorization of philanthropy and a low or negative view of the legal system.

Figure 3 maps the individual organizations onto the category map. Organizations cluster according to their response combination. For example, organizations in the upper right quadrant had positive perceptions in general but rated social valorization high and the legal framework low. Those on the far right of Dimension 1 but at the midpoint of Dimension 2, had positive perceptions in all categories. Organizations in the middle of the graph, color-coded blue, had mixed high/low perception combinations. Notably, they are a minority compared to most of the organizations placed on the graph’s outer edge. Another way of viewing Fig. 3 is that they represent the universe of perception profiles found in Chile’s philanthropic ecosystem, with each of the 16 nodes highlighting a unique segment.

Finally, it is possible to draw statistical 95% confidence ellipses for the average response of each organization or philanthropic actor type: companies, foundations, and CSOs. Figure 4 reveals a systematic ordering of actor perceptions toward the ecosystem. Of note is the left-to-right, upward-sloping diagonal relationship between the three organization types. When interpreting according to Dimension 1, companies overall have the most positive ecosystem perceptions, followed by foundations and CSOs.

However, Dimension 1 also interacts with Dimension 2, revealing in Fig. 3 a sub-group of companies with a positive perception of philanthropy’s social valorization and a negative view of the legal system. Conversely, while CSOs on average have a more negative perception of the ecosystem, there is a tendency (created by a sub-group) to view the legal framework positively and the social valorization negatively. Interestingly, foundation perceptions sit in the middle between the company and CSO extremes.

The MCA mapping of perceptions by organization type creates a representation of an underlying structure in the Chile’s philanthropic ecosystem. In Fig. 4, companies occupy a more positive position within the field, as the main private suppliers of donations, followed by foundations and CSOs. CSOs express greater negativity about their position, especially as they are fund recipients from an ever more concentrated donor supply. Foundations, which, in Chile are both donors and implementers, have perceptions midway between companies and CSOs.

We interpret these results as a demonstration of the systematic impact of the “objective” donor concentration (question 1) on the “subjective” perceptions of the Chilean philanthropic ecosystem (question 2). Findings indicate that the resource inequality and related power asymmetries suggested by the three critiques of inequality in philanthropy exist and may relate to systematic differences in ecosystem perceptions.

Question 3: What Factors are Associated with Inequality Perceptions?

This section extends the MCA mapping by first generating hypotheses about which factors may be associated with differences in ecosystem perceptions and then testing their relationship. By design, the original Barómetro study measured two main categories of factors associated with actor perceptions of the Chilean philanthropic ecosystem: (i) structural and (ii) organizational. The first category refers to external sociological elements in a system which may create systematic differences in donation access. These include (a) legal framework information and (b) legal tax incentives. We hypothesize that organizations that lack information or have difficulty understanding the legal framework will be at a structural disadvantage in the ecosystem. The second category of factors refers to “internal” organization-specific policies and capabilities, including (a) fundraising policy, (b) size and age, which proxies for capabilities, and (c) collaborative capacity. These capabilities are especially critical for the performance of philanthropic organizations in development contexts, often characterized by weak or evolving institutions (Bird & Leon, 2022). We thus expect to find a relation between the level of organizational capability, which can differ within organization type, and ecosystem perceptions.

Methodology: Regression Analysis

A continuous instead of the dichotomous or dummy version of the perception variables constructed to map perceptions were used as dependent variables in ordinary least squares (OLS) multilinear regressions. For this analysis, independent variables to test relationships with perception variables included organization type, age, and size (e.g., number of employees, revenue); region of operation; investment area; and dichotomous variables for alliance use, reporting practices, and fundraising policy. The same base model was used to test each hypothesized association, except where otherwise indicated.

Structural Factors

Information Effect

We hypothesize that organizations, especially CSOs, with better access to information about the legal system will have more positive perceptions. To test this association, we use region as a proxy, reasoning that those located in Santiago, the capital, will have more positive perceptions compared to organizations located outside it. To explore this, we regressed perception variables on a region dummy variable interacted with organization type, using regional recipient CSOs as the base comparison.

Table 3 (Information) indicates that the most positive perception of the legal system is for business and foundations located in Santiago, suggesting that the legal system is better understood by them. These actors may have more legal resources to decipher the system or the system is easier to understand because it was designed with them in mind, or both. Yet regional CSOs also express more positive perceptions of the legal regime compared to Santiago-based CSOs, and regional businesses and foundations, indicating that information, as proxied by distance from the capital, may not be the core issue. One possible explanation is that information flow between Santiago-based donors and region-based recipient CSOs may generate greater legal understanding. Further examination of the geography of information flows between organizations is needed. Regardless, these results indicate that, for reasons needing study, regional businesses and foundations and, curiously, recipient CSOs in Santiago operate with a degree of imbalance in the philanthropic ecosystem.

Legal Framework Effect

The legal system provides different incentives for each social investment area. Donors (companies and foundations) may therefore perceive some incentives more positively or negatively depending upon the donation legislation, e.g., culture vs. science. Furthermore, donors who work in thematic areas with explicit tax incentives may have more positive perceptions than those giving to areas with no incentives, e.g., culture vs. environment. To explore this hypothesis, we regressed perception outcomes on dummies for organizations working in investment areas.

Table 3 (Incentives) partially supports our hypothesis. Companies and foundations donating to culture have positive perceptions of legal understanding, perhaps because of the legislation passed in 2014. Furthermore, environmental donors have a negative perception overall and in terms of incentives, which makes sense given the lack of tax incentives for environmental giving. Finally, although a legal framework exists for science, perceptions are negative for incentives, indicating a critical policy barrier to address. In sum, these results indicate how the legal system favors certain philanthropic endeavors, providing opportunities for future study of implications for resource inequality and power imbalances among actors working in different thematic investment areas.

Organizational Factors

Fundraising Policy Effect

Those organizations who have explicit funding (donors) or fundraising (recipients) policies may have more positive perceptions, suggesting that inequality could be addressed by building better organizational capacity toward philanthropic practice. To test this hypothesis, we interacted the use of donor/fundraising policy with businesses and recipient CSOs types and regressed perception outcomes on them (foundations were not included since in practice they are often both funders and recipients).

Table 3 (Fundraising policy) reveals several findings. First, compared to non-donor companies, donor companies and recipients (regardless of whether they have an explicit fundraising policy) have a positive perception of legal understanding. Recipient CSOs without fundraising policies report a positive perception of legal incentives, while recipient CSOs with fundraising policies, have a negative perception of the social valorization of philanthropy. Although the former result seems counterintuitive, one explanation may be that recipient CSOs without fundraising policies lack a policy because fundraising is not a priority revenue stream and they rely on other financing strategies. The negative perception of social valorization of recipient CSOs with fundraising policies likewise may reflect organizational reliance on fundraising and the challenge of navigating different laws.

Size and Age Effects

Another factor may relate to overall capabilities, i.e., those organizations with more capabilities will have more positive perceptions because they have the experienced-based know-how to operate in the system. Both size and age may serve as proxy for organizational capability. To test the effect of size, perception outcomes were regressed on a revenues variable. Table 3 (size and age) suggests that larger companies have more positive views of cooperation in the system and marginally better overall perception.

To test for recipient CSO and foundation age, perception outcomes were regressed on a dummy for organizations older and less than 10 years of age. Table 3 shows that CSOs and foundations with over 10 years of operation had more positive perceptions of legal understanding. No effects were found for other perceptions, suggesting that factors not affected by experience and organizational capacity building may be at play. The negative effects seen for younger organizations may also highlight entry barriers and other challenges.

Collaborative Capacity Effect

The development of collaborative capacity may foster positive perceptions of the philanthropic ecosystem. For example, results from the legal information hypothesis suggested that a symbiotic relationship may exist between Santiago-based donors and CSOs outside the capital. The experience of working with other ecosystem actors may facilitate knowledge and capability transfer between organizations and foster positive perceptions of the ecosystem. To further test this relationship, we examined whether organizations with established alliances or reporting practices had more positive perceptions. We regressed perception outcomes on a dummy variable of whether organizations reported having alliances and engaging in donor/recipient reporting practices, respectively.

Table 3 (Collaboration) shares results. Organizations with alliances had more positive perceptions of collaboration ease. As with alliances, reporting relationships may reflect tensions between actors in the ecosystem. Regardless, results are suggestive and more exploration is needed since we merely detect statistical associations but not cause.

Conclusion

This study offers an initial theoretical framework for establishing the existence of resource inequality and associated power imbalances in Chile’s national donation system and understanding the role they may play in the philanthropic ecosystem. An analysis of public administrative data revealed a trend of donor concentration and a stagnation in the number of donors and total amounts donated, within the context of a disjointed legal framework that encourages CSO formation, but without concomitant donor incentives (question 1). We then demonstrated the effects of the inequality between donor supply and funding demand by mapping the subjective perceptions of philanthropic actors. Corporate donors expressed the most positive perceptions, followed by foundations and recipient CSOs (question 2). This evidence indicates that a resource dependence perspective situated within an organizational field framework may help guide future research. Finally, subsequent analysis deepened understanding of the factors associated with positive and negative perceptions of the ecosystem by showing how structural and organizational factors relate to perceptions of the donation system (question 3).

Chile exemplifies the effects of a disjointed and dispersed incentives policy, which differentially benefits companies and, to a lesser extent, foundations. We would predict that comparable dynamics are playing out throughout Latin America given similarities in (i) sociocultural influences on philanthropic practices (Letts et al., 2015) and (ii) affinities in legal frameworks regulating donations and CSOs (Aninat et al., 2022). Likewise, these dynamics may also be present in other middle-income countries navigating the creation of national wealth and an international shift in ODA. More global analysis of philanthropic ecosystems is necessary to understand the positive and negative role inequality may play. Public policy, civil society regulation, and donation tax incentives all exert a critical influence in the creation and maintenance of ecosystem inequality. Furthermore, donation incentives are the rule and not the exception, even in countries with different political systems (OECD, 2020).

These insights highlight multiple areas for future empirical and theoretical exploration of the factors driving inequality within a philanthropic ecosystem and their effects on social value creation. More effort could be made in Chile to communicate and clarify the existing legal framework to CSOs or provide legal support for those seeking to understand and take advantage of tax incentives. In general, tax incentives are evaluated according to how well they foster contributions for public goods (an equation that analyzes fiscal costs produced through decreased collection compared with resources added through donations). But future research should consider how to analyze the effects of different incentive structures on donor concentration, examining situations of either few donors with high power/influence or fewer CSOs with the capacity to participate in the ecosystem and overcome bureaucratic barriers. Such analysis may combine legal, fiscal, and economic understanding with an organizational sociology perspective, such as that proposed here, to understand other philanthropic ecosystems in Latin America. Finally, another area of exploration is the role of stakeholder dynamics and behavior in the generation of ecosystem inequality. Practices such as collaboration, reporting, and other elements, e.g., “collaborative” infrastructure (e.g., associations of CSO organizations), could have a corrective effect on the inequality and dynamics created.

Notes

An exception from the gray literature is diagnosis of the USA reported in the annual “Gilded Giving” reports from the Institute of Policy Studies since 2016.

To inform ant-trust decisions, regulators use economic measures of market concentration called the Herfindahl–Hirschman index. Imagine a sector with “n” participant agents, each with a market share. The index squares the market share of each and adds them, resulting in a number between 0 and 1. In this formulation, donors would represent the “supply” share of philanthropic capital and recipients the “demand” for funds. According to the U.S. Department of Justice, an index below 0.15 reflects low levels of concentration. If the index is between 0.15 and 0.25 there is moderate concentration. Indices above 0.25 are considered high. See https://www.justice.gov/atr/herfindahl-hirschman-index.

The COVID-19 pandemic affected 2020 donation amounts.

Unlike parametric statistics, which is a deductive approach that makes population-level inferences based on samples and distribution assumptions, MCA is an inductive technique based on geometric data analysis (Le Roux & Rouanet, 2010). Similar to principal component analysis (PCA), which identifies latent factors emergent from linear continuous variables, MCA plots categorical responses onto multidimensional geometric scales to identify how responses cluster, thus enabling the mapping of both response categories and individual actors in a geometric space. This is done by mapping categories of outcomes and, according to the position of these categories, overlaying where groups of actors, based on their individual responses, lie in the geometric space (thus serving as an analog for the social structure or ecosystem). In this study, the mapping depicts relations in the philanthropic ecosystem. An added advantage of MCA is that the inductive statistical analysis can be used with small samples.

To identify a variable’s threshold contribution, the rule of thumb is to count the number of categories in the model (eight, given the use of four dummy variables) and use this number as a denominator to calculate the threshold for the model, with 100 as the numerator (Le Roux & Rouanet, 2010). The threshold for our model is thus 100/8 or 12.5. Therefore, those categories with values below 12.5 should not be considered in interpretation of the model. Importantly, seven of eight categories met contribution thresholds for one of the two main dimensions in the results, with one category falling below 10.

References

Aninat, M., Vallespin, R., and Villar, R. (2022). Reglas e incentivos: Mapeo del marco legal para las organizaciones sin fines de lucro y la filantropía en América Latina y el Caribe. CEFIS, Lilly Family School of Philanthropy-Indiana University, WINGS. Accessed at https://cefis.uai.cl/assets/uploads/2022/05/estudio-cefis-wings-iupui.pdf

Aninat, M., & Fuenzalida, I. (2017). Filantropía institucional en Chile Mapeo de filantropía e inversiones sociales Centro de Filantropía e Inversiones Sociales de la Escuela de Gobierno de la. Santiago: Centro de Filantropía e Inversiones Sociales de la Escuela de Gobierno de la Universidad Alfonso Ibáñez.

Aninat, M., & Vallespin, R. (2019). Primer barómetro de filantropía en Chile: Tendencias e índice de desarrollo Centro de Filantropía e Inversiones Sociales. Santiago: Centro de Filantropía e Inversiones Sociales, Escuela de Gobierno, Universidad Adolfo Ibáñez.

Appe, S. (2018). Directions in a post-aid world? South-South development cooperation and CSOs in Latin America. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 29, 271–283.

Appe, S., & Pallas, C. L. (2018). Aid reduction and local civil society: Causes, comparisons, and consequences. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 29, 245–255.

Bang Carlsen, H., Doerr, N., & Toubøl, J. (2020). Inequality in interaction: Equalising the helper-recipient relationship in the refugee solidarity movement. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-020-00268-9

Berger, G., Aninat, M., Matute, J., Suárez, M. C., Ronderos, M. A., Oliver, M., Johansen, E., Bird, M., & León, V. (2020). Hacia el fortalecimiento de la filantropía institucional en América Latina. Lima: Fondo Editorial de la Universidad del Pacífico.

Bird, M., & Leon, V. (2022, forthcoming). Strengthening global institutional philanthropy: Insights from an Organisational Capacity Index in Latin America. Voluntary Sector Quarterly.

Bird, M., & Leon, V. (2019). A will in search of way: Philanthropy in education in Peru. In G. Steiner-Khamsi, J. Monks, & A. Terway (Eds.), Philanthropy in education (pp. 124–139). Amsterdam: Edward Elgar.

Calleja, R., & Prizzon, A. (2019). Moving away from aid: The experience of Chile. Overseas Development Institute Report.

Callen, J. L., Klein, A., & Tinkelman, D. (2010). The contextual impact of nonprofit board composition and structure on organizational performance: Agency and resource dependence perspectives. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 21(1), 101–125.

Carnegie, A. (1889[1901]). The Gospel of Wealth. In A. Carnegie (Ed.), The Gospel of wealth and other essays. New York: The Century Company (pp. 1–44).

Carroll, D. A., & Stater, K. J. (2008). Revenue diversification in nonprofit organizations: Does it lead to financial stability? Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 19(4), 947–966.

Centro Políticas Públicas UC. (2016). Mapa de las organizaciones de la sociedad Civil 2015. Primer informe de resultados del proyecto Sociedad en Acción. Accessed at https://politicaspublicas.uc.cl/content/uploads/2020/07/PDF-Brochure-Mapa-de-las-Organizaciones-1.pdf

Centro Políticas Públicas UC. (2020). Mapa de las organizaciones de la sociedad Civil 2020. Informe proyecto Sociedad en Acción. Accessed at https://politicaspublicas.uc.cl/content/uploads/2020/07/MAPA-ORGANIZACIONES-DE-LA-SOCIEDAD-CIVIL-2020-_-JULIO-1.pdf

Collins, C., & Flannery, H. (2022). Gilded giving 2022: How wealth inequality distorts philanthropy and imperils democracy. Washington, D.C.: Institute for Policy Studies.

DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48, 147–160.

Fifka, M. S., Kühn, A. L., Loza Adaui, C. R., & Stiglbauer, M. (2016). Promoting development in weak institutional environments: The understanding and transmission of sustainability by NGOS in Latin America. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 27, 1091–1122.

Frumkin, P., & Keating, E. K. (2011). Diversification reconsidered: The risks and rewards of revenue concentration. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, 2(2), 151–164.

Godfrey, J., Branigan, E., & Khan, S. (2016). Old and new forms of giving: Understanding corporate philanthropy in India. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 28, 672–696.

Hannan, M. T., & Freeman, J. (1989). Organizational ecology. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Herro, A., & Obeng-Odoom, F. (2019). Foundations of radical philanthropy. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 30, 881–890.

Irarrázaval, I., Hairel, E., Sokolowski, W., & Salamon, L. (2006). Comparative Nonprofit Sector Project Chile. https://ccss.jhu.edu/publications-findings/?did=38

Irarrázaval, I., & Streeter, P. (2020). Mapa de las organizaciones de la sociedad civil. Santiago: Centro de Políticas Públicas UC, Fundación Chile+Holy.

Kang, L. (2019). What Does China’s Twin-Pillared NGO funding game Entail? Growing diversity and increasing isomorphism. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 30, 499–515.

Kapiszewski, D., Levitsky, S., & Yashar, D. (Eds.). (2021). The inclusionary turn in Latin American Democracies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kim, M. (2017). The relationship of nonprofits’ financial health to program outcomes: Empirical evidence from nonprofit arts organizations. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 46(3), 1–24.

Le Roux, B., & Rouanet, H. (2010). Multiple Correspondence Analysis. Thousand Oaks CA: Sage Publications.

Letts, C. W., Doherty Johnson, P., & Kelly, C. (2015). From prosperity to purpose: Perspectives on philanthropy and social investment among wealthy individuals in Latin America. UBS Philanthropy Advisory and Hauser Institute for Civil Society.

Leiter, J. (2005). Structural Isomorphism in Australian Nonprofit Organizations. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 16, 1–31.

Leiter, J. (2013). An industry fields approach to isomorphism involving Australian Nonprofit Organizations. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 24, 1037–1070.

Leon, V., & Bird, M. (2018). Hacia una nueva filantropía en el Perú. Lima: Editorial de la Universidad del Pacifico.

Mattes, R., & Moreno, A. (2018). Social and political trust in developing countries: Sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America. In E. M. Uslaner (Ed.), Oxford Handbook of Social and Political Trust. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Nicholson, W., & Snyder, C. (2007). Intermediate Microeconomics. Boston: Cengage.

OECD. (2020). Taxation and philanthropy, OECD Tax Policy Studies. Paris: OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/df434a77-en

OECD. (2021). Private Philanthropy for Development: Data for Action. Paris: OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/cdf37f1e-en

Pasic, A., Osili, U., Rooney, P., Ottoni-Wilhelm, M., Snell Herzog, P., King, D., Pactor, A., Siddiqui, S. (2020). Inclusive Philanthropy. Stanford Social Innovation Review, Fall.

Pfeffer, J., & Salancik, G. R. (1978). The external control of organizations: A resource dependence perspective. New York: Harper and Row.

Pozzebon, M., Tello-Rozas, S., & Heck, I. (2021). Nourishing the social innovation debate with the “social technology” South American research tradition. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 32, 663–677.

Reich, R. (2018). Just giving: Why philanthropy is failing democracy and how it can do better. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Reich, R., Cordelli, C., & Bernholz, L. (Eds.). (2016). Philanthropy in democratic societies. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Sanborn, C., & Portocarrero, F. (Eds.). (2005). Philanthropy and social change in Latin America. Cambridge: David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies Harvard University.

Schmitz, H. P., Mitchell, G., & McCollim, E. (2021). How billionaires explain their philanthropy: A mixed-method analysis of giving pledge letters. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 32, 512–523.

Singer, P. (2009). The life you can save: Acting now to end world poverty. New York: Random House.

Scott, R. (2013). Institutions and organizations: Ideas, interests, and identities. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publishing.

Verbruggen, S., Christiaens, J., & Milis, K. (2011). Can resource dependence and coercive isomorphism explain nonprofit organizations’ compliance with reporting standards? Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 40(1), 5–32.

Verbruggen, S., Christiaens, J., Reheul, A., & Van Caneghem, T. (2015). Analysis of audit fees for nonprofits: Resource dependence and agency theory approaches. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 44(4), 734–754.

Villar, R. (2018). Las fundaciones en Colombia: Características, tendencias y desafíos. Bogotá: AFE Colombia.

Villar, R., & Puig, G. (2022). Las donatarias autorizadas: ingresos y donativos otorgados. In J. Butcher (Ed.), Generosidad en México III: fuentes, cauces, y destinos (pp. 143–181). Mexico: Porrúa, CIESC and Tecnológico de Monterrey.

Villar, R., Vallespin, R., & Aninat, M. (2020). Hacia un nuevo marco legal para las donaciones en Chile: Análisis comparado Chile, América Latina, OCDE. Santiago: Centro de Filantropía e Inversioes Sociales, Escuela de Gobierno, Universidad Adolfo Ibáñez.

von Schnurbein, G., Rey-Garcia, M., & Neumayr, M. (2021) Contemporary philanthropy in the spotlight: Pushing the boundaries of research on a global and contested social practice. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 32(2) 185–193. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-021-00343-9

Wilde, O. (1891[1969]). The soul of man under socialism. In R. Ellmann (Ed.), The artist as critic: Critical writings of Oscar Wilde. New York: Random House.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Edicson Luna Roman, Rocío Vallespin Martinez, and Mariana Loli Hassinger for excellent research assistance. Any errors are our own.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest in the preparation of this study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Bird, M.D., Aninat, M. Inequality in Chile’s Philanthropic Ecosystem: Evidence and Implications. Voluntas 34, 974–989 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-022-00541-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-022-00541-z