Abstract

Civil society leadership training programmes are a new phenomenon, and they are often overlooked by civil society scholarship despite being linked to the professionalisation of the sector. In this article, we examine 14 Swedish leadership programmes in order to identify leadership ideals in the sector. Drawing on the notion of ‘symbolic boundaries’, we argue that leadership programmes produce horizontal boundaries in relation to other societal sectors and vertical boundaries between leaders of the sector and other members. Together, these symbolic boundaries form a leadership ideal that detaches leaders from their organisation and internal democratic processes, instead depicting leadership as a question of personal characteristics and values. Leaders in the sector need to be authentic and to anchor their leadership in the personal values they hold. Theoretically, our analytical model may prove useful in the study of other empirical phenomena in civil society.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Civil society has historically relied on the internal organisational training of its leaders, and this has allowed people to make a career within one’s organisation or issue area. Such education of future leaders forms a long process as potential candidates rise within organisational ranks and are socialised to meet the demands of the particular organisation (see Pauli, 2012). However, a new type of training programme for civil society leaders challenges this model as sector-wide capacity-building organisations, private businesses, and consultancy firms have started to develop training programmes designed to educate civil society leaders. Such leadership training programmes assume generic civil society leadership qualities and requirements that transgress organisational differences. While these leadership programmes can be considered a new arena for individuals to gain leadership competence and experience, they also shape the ideals of leadership for the entire sector.

The overall purpose of this article is to investigate the ideals of civil society leadership produced by these programmes. The article develops an original analytical approach drawing on Lamont’s sociological theory of boundary work (Lamont et al. 2015; Lamont and Molnar, 2002 and Pachuki et al. 2007). Based on this analytical framework, the article is guided by the following two research questions: ‘Which boundaries construct the foundation for civil society leadership’ and ‘How does the combination of horizontal boundaries (which separate civil society from other sectors) and vertical boundaries (which separate leaders in civil society from those being led) shape the ideals of civil society leadership?’ We argue that this analytical approach is particularly relevant for the study of civil society leadership training programmes because their aim is to train a cadre of civil society leaders that are both different from leaders of other sectors and different from the members of the organisation who are to be led.

This article contributes empirically to current research on civil society leadership through our particular focus on leadership training. Existing research on leadership training has often focused on the design and impact of such programmes with respect to the performance of leaders and often with a particular interest in higher education (see, for instance, Malcolm et al. 2015; Mirabella, 2007; Mirabella et al. 2015, 2019; O’Neill, 2007). While these perspectives have their merits, they tend to overlook the norms and ideals that these programmes produce concerning civil society leadership and thus how such programmes form part of the constitution of civil society leadership.

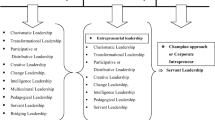

This article moreover contributes theoretically to debates on models of civil society leadership (e.g. do Adro and Leitão. 2020; Hodges and Howieson. 2017; Ronquillo et al. 2012; Terry et al. 2020). In recent years scholars have investigated the significance of transactional (Rowold and Rohman. 2009), charismatic (Hernandez et al. 2001), transformational (Valero et al. 2015), and ethical leadership models (Constandt and Willem, 2019) concerning what civil society leaders do and how they relate to members, followers, and stakeholders. Such research has allowed for the comparison of models across sectors and has shown their significance for different types of organisations, but they run the risk of providing an overly individualistic view on leaders and leadership, whereas previous research has focused on the benefits and drawbacks of different leadership models, less focus has been directed to how ideals of civil society leadership are shaped and the wider significance these values have for civil society. The use of horizontal and vertical boundaries and boundary work is a way of addressing civil society leadership and civil society leadership training as both expressing and reproducing norms about leadership that structure the sector.

Sector-wide civil society leadership training programmes can now be found in several countries (e.g. in the UK, see ACEVO, 2020), and we consider Sweden to be a suitable context for our research purposes. Swedish civil society leadership has historically relied on internal training, but in the last decade internal training has been complemented by sector-wide programmes that have gained strength in numbers and importance (Harding, 2019; Hvenmark and Segnestam Larsson. 2012; Wijkström and Åkerblom. 2002). This shift provides fertile ground to empirically investigate emerging ideals of leadership and to develop our theoretical framework.

The article proceeds as follows. First, we develop our theoretical framework before discussing our methodological strategy. In the empirical discussion, we first present an overview of leadership programmes in Sweden and then examine the horizontal and vertical boundary work of these programmes. In the concluding section, we summarise our key findings and discuss their implications.

Towards A Framework for Analysing Horizontal and Vertical Boundaries

The theoretical perspective of boundary work offered by Lamont and colleagues (e.g. Lamont et al. 2015; Lamont and Molnar, 2002 and Pachuki et al. 2007) follows a growing interest in sociological approaches to the study of civil society (e.g. Dean, 2020). The theory of boundaries and boundary work originates from the sociological perspective offered by Bourdieu, and scholars continuing his legacy, which suggests that education and training programmes can be studied to capture leadership ideals and the forms of cultural capital that underpin them. Bourdieu famously proposed that educational institutions are significant with respect to the reproduction of class structures, arguing that the lower academic performance of working-class students does not correspond to reduced ability, but to institutional biases that favour familiarity with the culture of the dominant class (see Lamont et al. 2015). Education systems tend to reward the knowledge that dominant groups in society are socialised to acquire, which gives groups that have a deep familiarity with this knowledge an advantage. In turn, this naturalises class divisions, and the reproduction of elites is veiled when the arbitrariness of inequality is made to appear as natural. Hence, certificates, titles, and diplomas legitimise the existence of certain types of leaders at the top because they signal that there is a meritocratic logic explaining why small groups accumulate a disproportionate share of resources (Bourdieu and Passeron, 1977).

Like other social fields, civil society has its own set of ideals, distinctions, and sub-groups that structure how it operates. To make sense of this, the notion of ‘symbolic power’ is useful. In Wacquant’s (1993) interpretation, Bourdieu’s oeuvre is seen as an explication of the workings of symbolic power, that is, the capacity of systems of meaning to protect and strengthen unequal relations of power. Following Bourdieu, Lamont stresses the creation of distinction (Lamont et al. 2015) and proposes that ‘symbolic boundaries’ denote the figurative demarcations that separate groups from each other, making it possible to order them hierarchically. Symbolic boundaries are recognisable yet informal and can be seen as concrete expressions of social distinctions based on cultural capital that is constantly renegotiated and changing. The concept of ‘boundary work’ thus pinpoints how symbolic boundaries are upheld by the re-inscriptions and re-iterations of already-existing distinctions, which can be seen as a more agent-oriented version of the social distinctions that Bourdieu theorised. This approach assumes that forms of differentiation are needed in order for social orders to be established. Fields, sectors, and social groups can be studied with respect to how they are divided through symbolic boundaries, which in turn have social, political, and organisational consequences.

Lamont’s boundary-work approach has had significance for the study of a wide range of social and political phenomena. For instance, Gieryn (1999) examined the rhetorical practice of separating ‘real science’ from academic work that did not quite qualify as science as a practice that is necessary in order to form an identity and self-image as a ‘real scientist’. It has been less used in studies of civil society despite the fact that it has analytical affinity to key debates that have shaped the understanding of civil society and the third sector in recent years.

The discussion on sector differences is an illustration of the potential usefulness of the approach. Some researchers describe societal sectors as analytically and empirically separable, which has led to extensive research into the size and composition of third-sector activities compared to other sectors (e.g. Salamon and Sokolowski 2016; Enjolras et al. 2018). Others conceptualise the sector as ‘an intermediary area’ (e.g. Evers and Laville. 2004), indicating that sector differences are less obvious and thus leading to studies of sector hybridity (e.g. Brandsen et al. 2005). Although scholars have conceptualised this in different ways, we argue that an overarching theme in these debates is the construction of sector differences as horizontal boundaries between civil society, private business, and the state.

Another illustration of how boundary-work can be relevant in the context of civil society research is the extensive discussions on leadership models in general and ‘charismatic leadership’ in particular. Up until the 1970s, leaders were largely conceived of as managers (see Likert, 1961; McGregor.1967:167). In 1990, John Kotter argued that the failings of many organisations were the results of ‘over-management’ and a lack of ‘leadership’. In other words, leaders were directing, organising, and administrating, but not setting examples, formulating ideas, or projecting shared visions. Leaders are depicted as inspiring, charismatic, and value-driven, whereas ‘managers’ make use of their competence to administer organisations. Although not addressed as such, these models draw upon a vertical boundary between leaders and followers.

While these debates have developed into a mature research field in their own right, they similarly form the basis for our analytical framework and our two dimensions of boundary work, namely (a) horizontal boundary work producing a distinction of civil society from other sectors and (b) vertical boundary work distinguishing leaders in civil society from other actors in the sector. Horizontal boundary work thus regards how leadership programmes describe civil society as separated from other sectors and how its relations to other sectors are conceived in the programmes. Vertical boundary work focuses on how relations between leaders and followers are depicted and on the characteristics that are described as necessary to be a proficient civil society leader. Programmes that target civil society leaders rely on both of these.

Research Design and Analytical Strategy

Our empirical material included all Swedish civil society leadership programmes conducted between autumn 2018 and spring 2019 (see Table 1 for an overview). Because our primary aim was the study of civil society leadership, we excluded leadership training programmes that target leaders in civil society and other sectors as well as programmes that target a small sub-field of civil society. We moreover only included programmes with a national reach. Through our review we identified 14 cases of leadership programmes and producers (see Table 1).

Because our object of analysis is the programmes, we generally refer to the name of the programme rather than the name of the producers. Some of the programmes are run by umbrella organisations of civil society, and a few by private enterprises or specific organisations. Almost all programmes have been running for fewer than 10 years, reflecting the fact that civil society leadership training is a relatively novel phenomenon. All of these are part-time programmes, typically consisting of a few get-togethers, where participants are expected to prepare by reading study materials between meetings. In some cases, they are rather costly, indicating that the organisations that the participants represent are supposed to pay the fee. This means that applicants need to be backed by their organisation when applying. The material collected for this study included programme descriptions and educational materials such as online descriptions, schedules, marketing materials, and course literature. Data were gathered by contacting organisers and searching on their respective webpages.

This choice of material implies some limitations. First, we are not examining the results of leadership training for participants and cannot speak of exactly what is taught during the training sessions. In many cases, however, we have access to content descriptions from web-pages, from which we can see that the general marketing material corresponds to the content. Second, the fact that much of the material is geared to attract participants may imply that the descriptions of the programmes are rather vague and generic and that organisational democracy is downplayed. This, however, should also be the case with respect to the actual programmes, which attract participants from very different organisations. More importantly, we are not studying the causes of the leadership ideals inherent to programmes, but aim to describe and analyse them in their own right. Still, a broader picture of the significance of leadership training requires further studies, also involving interviews and the examination of study materials.

It follows from the above that this study is a text analysis, where the concepts of ‘symbolic boundaries’ and ‘boundary work’ have guided our interpretations. First, the material was sorted into the overarching categories of ‘distinctions of civil society’ (horizontal boundary work) and ‘descriptions of civil society leadership’ (vertical boundary work). This can be described as an initial thematic analysis (Spencer et al. 2003). Second, and following from the theoretical framework laid out above, we looked for sections of text where civil society is described and compared to other sectors (horizontal dimension) and how leaders are described and compared to other members of civil society (vertical dimension). This means that we carefully read all of the material in search for how the sector and leadership within the sector are described. After having coded such descriptions in the material, we analysed recurrent patterns within each theme and between the different cases. Thus, we noted recurrent descriptions of what civil society is and how it differs from the state and private business and which leadership characteristics are highlighted. By doing so, we arrived at a number of conclusions concerning the role of leadership programmes with respect to the vertical and horizontal boundaries of civil society leadership and how these dimensions together constitute leadership ideals of the Swedish third sector.

Civil Society and Leadership Training in Sweden

Swedish (and Scandinavian) civil society is shaped by its popular movement tradition, which began to emerge towards the end of the nineteenth century (Skov Henriksen et al. 2019). The term ‘popular movement’ commonly refers to the Scandinavian tradition of large membership-based associations functioning as representatives of certain groups vis-á-vis the state (Micheletti, 1995; Trägårdh. 2007). The historical roots of Swedish civil society in such popular movement organisations gave rise to a particular kind of leadership ideal. As these were democratic associations, with elected presidents and boards, it meant that members governed the organisations through democratic processes. Thus, to act as a leader in a popular movement organisation required leaders to be able to represent the members and maintain connections with the groups that they were elected to represent. The close and sometimes cordial relations, most notably between the Social Democratic Party and the wider labour movement, meant that civil society often functioned as a form of a recruitment area for public service and political posts. Participation, training, and leadership experience in certain popular movement organisations became a ‘pathway to power’ because these organisations played key roles in shaping the state and society, and these attributes were important in developing policies within their particular area of expertise and engagement. Leaders of these organisations were public figures, and often with clear connections to the political scene.

The predominant model of internal training allowed organisations to control the production of human resources and cultural capital outside of formal education at universities, which meant that prospective leaders sought to enhance the kind of human capital valued by the organisation (see Pauli, 2012). Designing and running the internal training of prospective leaders was central because other educational institutions were not fully trusted or relevant. Taking part in internal training implied not only that participants developed their skills and expertise on the issues that the organisation worked with, but also that they developed their social networks within the movement as a way of amassing social capital.

It was within these internal training programmes that organisations shaped their leaders, and internal training served as a mechanism of socialisation of individuals into the norms and values connected to the movement or organisation in question. We can thus understand the internal training as a key element of what Broady (1998) refers to as ‘organisational capital’. Through such internal routes of training and socialisation, presumptive leaders could gain (and compete over) the necessary amounts of organisational capital to be able to shoulder the role of leading the organisation.

The development of sector-wide leadership training programmes might indicate that pathways to power are in the process of being transformed. This is partly a reflection of changing state-civil society relations because the system of interest representation has changed from a model of ‘corporatism’ to a much more open and competitive form of lobbying (Gavelin, 2018; Hermansson et al. 1999; Lundberg. 2017). The former built on a system of institutionalised contacts, negotiations, and joint decision-making between state authorities and a few selected peak organisations and their representatives. Today, government-civil society relations are much more marked by competition between a wider set of actors trying to influence policy and politics from both inside and outside the policy-making processes. These are processes that invite more informal relations with personal contacts and networks at the expense of arranged consultations (Garsten et al. 2015).

This means that internal socialisation, training, and recruitment have lost some of their significance because the organisational capital that previously shaped recruitment patterns now must be weighed in relation to other experiences and skills. Current trends of growing professionalisation contribute to this (Johansson et al. 2019). Training programmes offer an alternative route for advancement that is different compared to internal training because they presume that there are generic leadership qualities that can be taught outside of the specific organisation and that apply to leaders in civil society in general irrespective of which type of organisation they work for.

The Horizontal Distinction in Civil Society

The Sector of Ideas

The leadership programmes analysed here target civil society in general, thus presuming that the challenges and requirements of leaders are relatively similar across the sector. At the same time, leadership training specifically targeting civil society also presumes that these challenges and requirements are different from other sectors. If that was not the case, potential participants could just as well sign up for a general leadership training programme.

In the material, none of the programmes explicitly define civil society. The term is presented as taken for granted, denoting an existing social sphere in no need of specification for potential participants. This can be interpreted as a result of the fact that the programmes want to be able to target a broad market of customers. At the same time, the training materials are full of descriptions of what characterises the sector. The most dominant pattern is that civil society is depicted as entrenched with ‘ideas’ and ‘visions’, often linked to the ambition of creating a better world. This is also reflected in the denotation ‘idéburen sector’, which in Swedish literally means ‘the sector carried by ideas.’ The Fenix training programme describes this:

Civil society is driven by a clear idea that something of importance needs to be done. Provided this idea, a mission is formulated, which is perceived as a necessity. But like the Phoenix, resurrecting time and time again, civil society organisations need to continuously make real their idea and mission in their work. (Ideell Arena a)

Similar sentiments are expressed in a majority of programmes. However, it also needs to be noted that the quote does not specify what the guiding ideas of civil society are. Indeed, it is much more common to describe the importance of ideas and visions in general rather than their specific contents. On the occasions when substantial ideas are referred to, they tend to be broad descriptions of human rights and democracy. The general impression is that the symbolic boundaries surrounding civil society consist of this sector being guided by ideas and visions rather than by a specific set of ideas and visions, echoing how Alexander (2006) has described discursive constructions of the purpose of civil society.

It is quite common that civil society is described with respect to its function. For example, Volontärbyrån states that civil society ‘gives voice to people’, the umbrella association Ideell Arena (b) declares that ‘a strong civil society contributes to an open and democratic society’, and the consultancy firm PwC (2019) claims that there is a gap in society between people engaged in civil society who have high trust in societal institutions and people who are not engaged and who mistrust such institutions. In this way, civil society is characterised as serving a vital function in democratic societies.

Civil Society as a Complement

Seen as horizontal boundary work, to describe the sector as being driven by ideas and visions distinguishes civil society from other sectors. Meanwhile, in the material the traditional negative definition of civil society, as being neither part of the state nor a private business, is absent. However, relations to the public and private sectors recur in the material, although these are never described in conflictual terms. Rather, civil society is complementary – it is governed by its own specific logic, and it is needed because other sectors have other guiding ideals. Interestingly, this means that the historical function of free associations of channelling dissent and organising resistance is downplayed. We see few signs that the programmes target social movements or organisations operating in political struggles. Rather, the need for skilled leaders in the sector is entangled with the idea that civil society, being the sector of ideas, complements private business and public agencies.

Occasionally, differences with respect to public and private organisations are highlighted. Most often these regard challenges that are described as internal to civil society organisations and specific for this sector.

Decision-making in organisations of the sector of ideas is often slow and hard to grasp. This is a sector where representatives and staff have a desire to fulfil ideas with high ambitions. It is common to feel stress and insecurity with regards to what constitute good results. (Ledarinstitutet).

This description, taken from the IRMA program of Ledarinstitutet, represents a broader tendency in the material in which civil society is said to be characterised by a certain form of complexity stemming from the democratic steering of membership organisations and from the ideas that are said to be the defining feature of the sector. It is notable that organisational democracy is represented as bringing hardships for civil society leadership – problems that some of the training programmes present themselves as offering solutions to. Other challenges that recur in some of the programmes consist of depictions of increasing societal complexity, rapid changes in the world, and new challenges – where the role of civil society is highlighted but never specified.

To summarise, the horizontal boundary work in the material consists of defining the sector as being driven by ideas and visions. This is contrasted with public and private organisation that face other challenges due to their inherent characteristics. Descriptions of members of the sector as being guided by a strong ethos and high ambitions are presented as facts. However, it is rarely specified what these norms and ideals are – it is the sector of any ideas and visions. In addition, the sector of ideas and visions is described as complementary with respect to other social spheres, where civil society is supposed to serve a vital function in meeting a number of vaguely insinuated societal challenges and transformations. This characterisation of civil society creates a boundary that delineates inside from outside. By this characterisation organisations and actors that are not driven by ideas are excluded. However, the view of civil society as complimentary to other sectors and the absence of dissent and political struggle also excludes social movements and associations that see political struggle as their core mission.

The Vertical Distinction of Civil Society Leaders

Charismatic and Authentic Leaders

As we shall see, the horizontal distinction with respect to other sectors based on a characterisation of civil society as driven by ideas is related to vertical boundary work, stressing leadership ideals focusing on authenticity, charisma, and the personal values of leaders. Leadership programmes rest on separating leaders, who are the target group of the programmes, from other members of civil society.

In their description of leaders, it is notable that the leadership programmes do not focus on competencies or skills, but on personal characteristics and values. ‘Who you are’ appears to be more important than ‘what you do as a leader’. This is also reflected by the fact that some programmes complement formal selection criteria with more personal qualities and aspirations. For example, Värdebaserat ledarskap states that ‘personal growth, experience, and background’ are grounds for selection (Scouternas folkhögskola), while Ledarinstitutet declares that applicants are evaluated based on their willingness to develop as a person and to take on increased responsibilities.

Such ideals can be described in terms of ‘charismatic leadership’ (see Spoelstra, 2018), and these are clearly linked to the horizontal boundaries of civil society. Because civil society is seen as the sector of ideas and visions, leadership ideals of value-driven inspiration apparently blend well, despite the fact that the figure of the ‘charismatic leader’ was first developed in the private business sector and in politics. Here, the idea of the inspiring leader is linked to the greater ideas that civil society organisations are described as fighting for:

Our starting point is the unique ideas-based leadership, which means creating meaning and engagement as well as winning trust and making possible the core values of the organisation, internally and externally. Characteristics of the value-based leader are to be curious and engaged, to make visible the values of the organisation, to set free the power [of members] and joy, to sustainably create goal-fulfilment and results, to let decisions grow from below, to be able to lead the members in order to realise goals and visions, and to create fearlessness and room for new ideas to grow. (Ledarinstitutet)

In this way, the task for civil society leaders is to steer the organisation towards the values that the organisation strives to fulfil.

In some programmes, there is an even stronger tendency, indicative of a kind of personalised leadership. This is most prominent in Värdebaserat ledarskap (Value-based leadership), which focuses on allowing participants to reflect on their own personality and leadership while leaving aside the values of the organisation. One of the main aims of the programme is to help leaders to better get to know their own core values. The programme states that a primary ambition is:

…making participants aware of their values and to (…) use the groups as a mirror in order to help them see that they, as leaders and fellow human beings, actually live and act out their values. (Scouternas folkhögskola 2017)

Here, personal authenticity appears as the main quality of leaders, even further detaching the leader from their organisation and its members. Because personal core values ideally run through ‘all everyday decisions’, leadership is turned into a question of what kind of person you are, reaching far beyond one’s professional role. All of this is underpinned by a specific take on what values and norms are:

We, as leaders and project managers, are often asked which values this programme is based on. The most common way of working with values is from a normative perspective, that is, that someone has decided which values shall guide an organisation, a company, or an education programme. In Värdebaserat ledarskap, we are working with descriptive values, which means that we help participants to explore their core values and to express these verbally and in writing. (Scouternas folkhögskola)

In the context of the literature on leadership, these ideas are not particularly unique. Consider for example the distinction between ‘transactional leaders’, primarily following their job description, and ‘transformational leaders’, who are leading with visions (Spoelstra, 2018:11). Furthermore, according to Spoelstra (2018: 236–9), contemporary understandings of leadership are prone to incorporating an ethical dimension, highlighting ‘the spiritual’, ‘the responsible’, or ‘the authentic’ leader. This dimension is most pronounced in this particular programme, but similar tendencies are present in our material more generally.

Leaders Without Organisations

The strong focus on the individual leader and their beliefs implies that the organisation is relatively absent in the material. Organisational democracy only rarely figures in the leadership programmes’ presentations, which indicates that leadership is a top-down activity. The model is rather that leadership should harmonise with the values of the organisation and that leaders are expected to represent and embody the ideals that the organisation strives to fulfil, echoing how Dym and Hutson (2005) see ‘alignment’ as the primary indicator of leadership efficiency.

According to Kouzes and Posner (2007:16), the distinction between ‘leader’ and ‘manager’ implies that leaders do ‘extraordinary things’, rather than merely managing organisational operations. Hence, it comes as no surprise that the leadership programmes are not designed to teach competences with regards to how civil society organisations are run. Rather, leaders are described as inspiring followers, using their personal charisma to frame the values of the organisation. In this context, many programmes describe leadership as a response to the special challenges of civil society, which involves complex work in an environment where people strive to achieve good, but where decision-making can be slow. In this vein, Ledarinstitutet describes how such challenges are to be met as leaders need to:

…create meaning and engagement, while also gaining trust in order to make real the fundamental ideas of the organisation, internally as well as externally.

By this, leaders ‘frame the values of the organisation’ in order to:

…emancipate the power and joy of in a sustainable way and to create movement towards the goal fulfilment […] of the organisation. (Ledarinstitutet)

Forces external to the organisation, on the other hand, are seen as threats, potentially making the leader lose sight of the values and ideas of the organisation. Here, increasing societal complexity is referred to as a central contextual factor. In our present-day society, civil society leaders need values and ideas as guiding lights.

In this context, it is relevant to think about the critique of this leadership ideal as leaning on notions of superiority (see Sinclair. 2007; Ford et al. 2008; Harding et al. 2011) – especially considering that we are dealing with democratic organisations espousing ideals of equality and diversity. The focus on leaders as inspirational and value-based may imply that leaders are not conceived of as representing the interests of members or are seen as leaving questions of organisational values to members. Rather, the leader is depicted as steering the course of the organisation. From this perspective, the leadership ideals of the training programmes can be seen as legitimising hierarchical distinctions within civil society.

In summary, the vertical boundary work of the organisations results in depictions of leaders as inspirational and thus able to use their personal values to guide followers. The core virtue is authenticity, especially in Värdebaserat ledarskap, but it reappears also in other programmes. Overall, leadership is emphasised in favour of management, where leaders are elevated by their personal charisma and its transformational capacity, which is connected to the horizontal distinction of civil society as the sector of ideas. This simultaneously contrasts leaders with managers and members who are not capable of stirring belief in the same way, and it excludes forms of leadership based on democratic accountability. Despite the differentiation of civil society from other sectors, these leadership ideals are surprisingly similar to how the management literature describes the ideal business leader.

Conclusion

This article shows the emergence of a civil society leadership ideal that goes beyond leadership in particular organisations, whereas previous leadership ideals generally relied on norms and ideals associated with being a leader in a specific organisation driven by a unique mission, the ideals of civil society leadership in our material rather assume leaders to be mobile across an entire sector, albeit still striving to fulfil the goals of the organisations they currently work for. Hence, the boundaries of leadership programmes constitute core elements within a general leadership category for the entire sector. Of course, the material of this study does not allow us to formulate general conclusions about leadership ideals in Swedish civil society as a whole. However, we do believe that they can serve as a starting point for further studies.

Our analysis shows that civil society is distinguished by being ‘the sector of ideas’ and is considered a complement to the public and the private sectors. This is the horizontal boundary that shapes civil society leadership. This, in turn, is linked to how leaders are separated from members of civil society by being able to inspire followers by being authentic. Such a vertical boundary furthermore establishes a hierarchy of those leading and those being led. The leadership ideals shaped by the combination of these two boundaries are to a lesser extent tied to skills or a set of competences that leaders can learn, and is instead more closely linked to the personal characteristics of the leader.

The symbolic boundaries that we observed furthermore shape leaders in a distinctively positive light, while downplaying dissent, political struggle, and internal democracy. The consequences of such ideals become clear when put in contrast to establish forms of leadership in a Swedish and Scandinavian context (e.g. Skov Henriksen et al. 2019) because civil society leaders neither need to, nor are supposed to, act as representatives for members or constituencies. Their legitimacy rather depends on the kind of person the leader is and their ability to inspire and set positive changes in motion. Undoubtedly, this reflects structural changes in Swedish civil society as popular movement ideals and corporativist systems have lost significance and the commercialisation of civil society has paved the way for more individualistic forms of leadership. These findings have contextual limitations, but they open up for further research into leadership training in other countries and, more generally, for studies that examine to what extent such programmes are replacing or complementing the internal training occurring in civil society organisations.

From a theoretical point of view, and if we are to take Bourdieu and Lamont seriously, symbolic boundaries naturalise social differences. In parallel to Bourdieu’s argument about how symbolic capital creates the illusion that educational performance reflects skill and merit and thus makes class divides appear as natural, leadership programmes can be interpreted as justifying a divide between leaders and followers through the personal characteristics of leaders and their capability to be inspiring. The new ideals of civil society leadership thus shape and diffuse norms about what leaders in the sector should aspire to, while at the same time justifying such hierarchies. The dual focus on the leader being authentic and the imagery of civil society as being driven by ideas not only shapes leaders as being committed to a greater cause, but also requires that aspiring leaders should seek to fulfil such expectations. While it lies beyond the scope of this article, these emerging ideals most likely will have significance for the recruitment and advancement of leaders in the Swedish civil society sector.

To sum up, this article shows that horizontal and vertical boundaries operate in tandem, with the horizontal characteristics of civil society corresponding to the vertical distinction of leaders as being value-driven and authentic. This shows that we cannot focus on one set of boundaries, but rather that these need to be studied in conjunction because they are mutually interdependent for the constitution of civil society leadership. This challenges much of the empirical and theoretical research on civil society leadership that has been developed based on models. While this shows the significance of a boundary approach for the study of civil society leadership programmes, horizontal and vertical boundary work might be fruitful for civil society research more generally and might contribute to the literature on the distinctive character of civil society and its hybridisation. Arguably, this article thus opens up for further studies concerning horizontal and vertical boundaries and how they structure different aspects of civil society beyond our particular focus on leadership training programmes.

References

ACEVO. (2020). New & emerging leaders programme. ACEVO.

Alexander, J. C. (2006). The civil sphere. Oxford University. Press.

Bourdieu, P., & Passeron, J. C. (1977). Reproduction in education society and culture. Sage.

Brandsen, T., van de Donk, W., & Putters, K. (2005). Griffins or chameleons? HYBRIDITY as a Permanent and Inevitable Characteristic of the Third Sector. International. Journal. Public. Administration., 28(9–10), 749–765.

Broady, D. (1998). Kapitalbegreppet som utbildningssociologiskt verktyg. Skeptron Occasional Papers, No. 15, Uppsala University, Uppsala

Constandt, B., & Willem, A. (2019). The trickle-down effect of ethical leadership in nonprofit soccer clubs. Nonprofit Management Leadership 3, 401–417.

Dean, J. (2020). The Good Glow Charity and the Symbolic Power of Doing Good. Policy. Press.

Do Adro, F. J. N., & Leitão, J. C. C. (2020). Leadership and organizational innovation in the third sector: A systematic literature review. International Journal Innovation Studies 2, 51–67.

Dym, B., & Hutson, H. (2005). Leadership in Nonprofit Organizations. Sage. Publications.

Enjolras, B., Salamon, L. M., Sivesind, K. H., & Zimmer, A. (2018). The Third Sector as a Renewable Resource for Europe. Palgrave. Macmillan.

Evers, A., & Laville, J. L. (2004). Defining the third sector in Europe. In Adalbert Evers & Jean-Louis. Laville (Eds.), the third sector in Europe. Edward Elgar Publishing. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781843769774.00006

Ford, J., Harding, N., & Mark, M. (2008). Leadership as identity: Constructions and deconstructions. Palgrave Macmillan.

Garsten, C., B. Rothstein and S. Svallfors. (2015). Makt utan mandat. De policyprofessionella i välfärdssamhället. Dialogos Förlag, Stockholm.

Gavelin, K. (2018). The Terms of Involvement: A study of attempts to reform civil society’s role in public decision making in Sweden. Stockholm Universitet, Stockholm.

Gieryn, T. F. (1999). Cultural Boundaries of Science. University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Harding, T. (2019). The role of the popular movement tradition in shaping civil society leadership education in sweden. J Nonprofit Education Leadership 1, 18–39.

Harding, N., Lee, H., Ford, J., & Learmonth, M. (2011). Leadership and charisma: A desire that cannot speak its name? Human Relation., 7, 927–949.

Henriksen, L. S., K. Strømsnes and L. Svedberg (eds.). (2019). Civic Engagement in Scandinavia Volunteering Informal Help and Giving in Denmark Norway and Sweden Springer New York.

Hermansson, J., A. Lund, T. Svensson and P.O Öberg. (1999). Avkorporativisering och lobbyism, SOU 1999:121, Fakta info direkt, Stockholm.

Hernandez, C. M., & Leslie, D. R. (2001). Charismatic. Leadership. Nonprofit. Management. Leadership., 4, 493–497.

Hodges, J., & Howieson, B. (2017). The challenges of leadership in the third sector. Europeanl Management Journal 1, 69–77.

Hvenmark, J., & Segnestam Larsson, O. (2012). International mappings of nonprofit management education: An analytical framework and the case of sweden: International mappings of nonprofit management education. Nonprofit Management Leadership 1, 59–75.

Johansson, H., M. Arvidson, S. Johansson, and M. Nordfelt. (2019). Mellan röst och service - Ideella organisationer i lokala välfärdssamhällen. Studentlitteratur, Lund

Kouzes, J. M., & Posner, B. Z. (2007). The leadership challenge: The most trusted source on becoming a better leader. John Wiley.

Lamont, M., & Molnar, V. (2002). The study of boundaries in the social sciences. Annu Rev Soc 28, 167–195.

Lamont, M., S. Pendergrass and M. Pachicki. (2015). Symbolic Boundaries. In J. D. Wright (ed.) International Encyclopedia of the Social Behavioral Sciences, Elsevier:850-855

Likert, R. (1961). New patterns of management. McGraw-Hill.

Lundberg, E. (2017). Toward a new social contract? the participation of civil society in swedish welfare policymaking, 1958–2012. VOLUNTAS: Int. Journal. Vol. Nonprofit. Organ., 31, 1–22.

Malcolm, M.-J., Onyx, J., Dalton, B., & Penetito, K. (2015). Nonprofit management education down under: challenges and opportunities. Journal. Nonprofit. Education. Leadership, 4, 219–244.

McGregor, D. (1967). The professional manager. McGraw-Hill.

Micheletti, M. (1995). Civil Society and State Relations in Sweden. Aldershot: Avebury.

Mirabella, R. M. (2007). University-based educational programs in nonprofit management and philanthropic studies: a 10-year review and projections of future trends. Nonprofit. Volutanary. Sector. Quarterly., 36(4_suppl), 11S-27S. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764007305051

Mirabella, R., Hvenmark, J., & Larsson, O. S. (2015). Civil society education: International perspectives. Journal. Nonprofit. Education. Leadership., 4, 213–219.

Mirabella, R., Hvenmark, J., & J., and O.S. Larsson. (2019). Civil society education: national perspectives. Journal. Nonprofit. Education. Leadership., 1, 2–6.

O’Neill, M. (2007). The future of nonprofit management education. Nonprofit. Voluntary. Sector. Quarterly., 4, 169–176.

Pachuki, M., Pendergrass, S., & Lamont, M. (2007). Boundary processes: recent theoretical developments and new contributions. Poetics, 35, 331–351.

Pauli, P. (2012). Rörelsens ledare: Karriärvägar och ledarideal i den svenska arbetarrörelsen under 1900-talet. Göteborg Universitet, Göteborg.

Ronquillo, J. C., W.E. Hein, and H. L. Carpenter. (2012). Reviewing the literature on leadership in nonprofit organizations. In R. Burke and C. Cooper (eds.), Human Resource Management in the Nonprofit Sector. Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham.

Rowold, J., & Rohman, A. (2009). Transformational and transactional leadership styles, followers’ positive and negative emotions, and performance in german nonprofit orchestras. Nonprofit. Management. Leadership., 1, 41–59.

PwC. (2019). Så kan framtiden se ut för ideella organisationer. https://www.pwc.se/sv/branscher/ideell-sektor/ideella-organisationer.html. Retrieved by 13 of december 2020.

Salamon, L. M., & Wojciech Sokolowski, S. (2016). Beyond Nonprofits: Re-conceptualizing the Third Sector. Voluntas, 27(4), 1515–1545.

Scouternas folkgörskola. (2017). Kursplan Värdebaserat ledarskap. Stockholm: Scouternas folkhögskola.

Sinclair, A. (2007). Leadership for the disillusioned: Moving beyond the myths and heroes to leading that liberates. Allen Unwin Crows Nest

Spencer, L., J., Ritchie, W., O’Conner, G., Morrell, and R. Ormston. ( eds.) (2003). Qualitative Research Practice A Guide for Social Science Students Researchers. Sage London

Spoelstra, S. (2018). Leadership and organisation a philosophical introduction.

Terry, V., Rees, J., & Jacklin-Jarvis, C. (2020). The difference leadership makes? Debating. Concept. Leaders.UK. Voutary. Sector. Voluntary. Sector. Review., 11(1), 99–111.

Trägårdh, L. (2007). State and civil society in Northern Europe: The Swedish model reconsidered. Berghahn Books.

Valero, J. N., Jung, K., & Andrew, S. A. (2015). Does transformational leadership build resilient public and nonprofit organisations? Disaster. Prevention. Management: An. International. Journal., 24(1), 4–20.

Wacquant, L. (1993). On the tracks of symbolic power: Prefatory notes to Bourdieu’s “State Nobility.” Theory. Culture. Society., 3, 1–17.

Wijkström, F., & Åkerblom. C. (2002). Dolda arenor för (re)produktion av ett alternativt ledarskap? Föreställningar i texter om ledarskap i svenska folkrörelser. SSE/EFI Work Paper Series in Bus Admini 2004(17). Stockholm

Funding

Open access funding provided by Lund University. This Study was funded by Riksbankens Jubileumsfond (M17-0188:1) and The Swedish Research Council (2017–02578).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Altermark, N., Johansson, H. & Stattin, S. Shaping Civil Society Leaders: Horizontal and Vertical Boundary Work in Swedish Leadership Training Programmes. Voluntas 34, 1025–1035 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-022-00519-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-022-00519-x