Abstract

This article analyzes various roles of development practitioners (called outsiders) in five different cases of community-based development (CBD) in rural Iran. It provides a review of the literature on CBD and identifies three main types of roles fulfilled by outsiders to support indigenous development processes. These include preparing the ground, activating community-based organizations as participatory institutions, and taking on the role of brokers who bridge the gap between the local community and outside institutions—especially the state and market. From the analysis of empirical qualitative data collected during fieldwork in Iran, the article concludes that while the roles played by the outsiders in CBD interventions there correspond mostly to those identified in the literature, there are differences in their strategies of intervention and activities under each role which correspond with their contextual contingencies. Recognizing this variation is needed to deepen the understanding of CBD practices and help practitioners think about alternative perspectives and approaches.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

After more than 50 years of state-centered and top-down development practices in Iran, over the last two decades several reforms have given rise to community-based development (CBD) practices, supported by the state, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and foreign donors. This article focuses on this trend and analyzes the roles played by these ‘outsiders’ in supporting the establishment and growth of different types of CBD interventions. By ‘outsiders’ in this article, we mean different actors outside of the locality. Although the most important outsider in Iran is the government, other actors like international organizations (IOs) and businesses may also be considered as outside intervening actors. The empirical findings of this study on the role of such outsiders (based on five qualitative case studies) are compared with the roles of outsiders found in the scholarly literature in order to generate additional insights about their roles which merit greater attention by scholars and practitioners.

This section briefly outlines the historical context for our study. The Land Reform Law enacted in 1962 marked a turning point for society and politics in the rural communities of Iran. Following the passage of this legislation, farmers became the owners of the land and received financial loans for investment. Besides raising critical questions about the equitable land distribution and the loss of economies of scale, some critics argue that by dividing assets and creating individual properties, the policy destroyed the social organizing institutions which used to be an inseparable part of the farmers’ lives, such as systems of collective agriculture called Boneh and those of cooperative production called Vareh (Farhadi, 2008; Hesamian et al., 2005; Majd, 1987). The roles of landlords as governors, organizers, and intermediaries were taken over by the state bureaucracy and thus enhanced state power (Katouzian, 1974). Azkia and Ghaffari (2004) identify the resulting bureaucracy, centralization, and top-down planning as the most important causes of socio-economic problems in the rural communities after the Land Reform Law, and argue that these trends continued after the Islamic Revolution and even intensified with the extension of the state bureaucracy.

Following the Islamic Revolution in 1978, and especially from the beginning of the Sazandegi (Construction) period in 1989, the government started widespread development programs in rural areas, mostly aimed at physical and infrastructural improvement. Thanks to its oil revenues, the government of Iran was able to spend significant amounts on the construction of roads and access to electricity, drinking water, gas, and in recent years the internet, in even the remote corners of the country.Footnote 1 Academic studies have shown that these approaches have led to a certain passive attitude on the part of the population, with expectations of free service from the government (a ‘begging mentality’) and less productive economic behavior (Anbari, 2016; Rafipoor, 1997). Indeed, the new road infrastructure facilitated the commute to the cities and the sales of cheaper consumer products in rural areas, leading to the adoption of new lifestyles and feelings of relative deprivation in local communities (see Rafipoor, 1986 as cited in Rafipoor, 2014). The depletion of water reservoirs and the destruction of rangeland caused by global climate change and unsustainable use of natural resources resulted in increased poverty and unemployment (Jalili Kamju & Nademi, 2019). As we can see in Table 1, the rural population as a share of total population decreased significantly, while the relatively stable household sizes imply that rural fertility rates did not decrease and rural mortality rates did not increase significantly. The fact that the share of the rural population in the total population dropped by more than half during the period 1976–2016 is thus mainly due to rural out-migration to the cities—especially metropoles—in the hope of finding jobs and a more comfortable life. However, in reality many of the migrants ended up living on the margins of urban society, dealing with many new life issues and social harms (Amiri et al., 2014). The majority of migrants are youths in the productive ages of 25–64, increasing the ‘dependency ratio’ in rural communities (Iran Planning and Budget Organization, 2017).

Given the overall negative track record of rural development approaches in Iran, a new wave of national grassroots development activities started to take hold since the early 2000s.Footnote 2 The organizations promoting such grassroots development support local self-organizing institutions in order to empower the community as a whole, by reinforcing internal agency, cooperative linkages, and greater local participation. In the current wave, the public, private, and NGO sectors are unanimous in stressing the role of Mardom (people), youth, and local institutions in addressing the failures of formal institutions to resolve social issues like poverty, inequality, and poor health services (this is evident simply by looking up the word Mardom ‘ ’ in Google Trends in recent years).

’ in Google Trends in recent years).

However, there is a lack of reliable studies investigating and evaluating these more recent local development practices in Iran. While there are many articles on economic, technical, and industrial development approaches in the country, there are only a few on community-based and participatory approaches. Most of these articles have explored the factors of and barriers to community participation in rural areas (Aref et al., 2009; Kolahi et al., 2014; Kamali, 2007; Dadvar-Khani, 2012; Rezvani et al., 2009) and the functions of community-based organizations (CBOs) in the development process (Barimani et al., 2016; Firouzabadi & Jafari, 2016). But there is still a research gap about Iran—especially in international publications—on the interventions in the recent wave of Iranian development programs and the roles outsiders played to address these barriers to participation and to form the CBOs.

We chose the CBD framework and concept as the strand of literature which is the most applicable to this new wave of development in Iran. Although there is a significant body of literature on CBD and other participatory and bottom-up approaches, and they are widely used by international organizations around the world, there are still many open questions and debates for more study. Mansuri and Rao (2013) reviewed more than 500 empirical studies of participatory development interventions. As they report:

Allocations of many millions of dollars are justified by little more than slogans, such as ‘empowering the poor,’ ‘improving accountability,’ ‘building social capital,’ and ‘improving the demand side of governance.’ Part of the conceptual challenge lies in understanding what these notions mean, how they fit within broader conceptions of development policy, and how they differ across diverse contexts and over time. (p.49)

They criticize most of the participatory projects by the World Bank and other organizations that assume the same trajectories and outcomes, making ‘the design and even the language of World Bank project documents often seem to be cut and pasted from one project to the next’ (p.297). Such projects ignore the differences that may arise due to different contexts (history, social structure, geography, and politics) and the learning-by-doing and long-term nature of CBD.

Indeed, those authors who have tried to theorize CBD have mostly focused on similar main principles as absolute solutions for every time and everywhere—such as community agency, participation, and social capital (Bhattacharyya, 2004; Frank & Smith, 1999; Mathie & Cunningham, 2003; McLeroy et al., 2003; Murphy, 2014). However, these principles and their limitations need to be defined based on real case studies. For example, the concept of ‘participation’ is still vague, and its boundaries and scope are not defined accurately in relation to other concepts like democracy, self-sufficiency, and indigeneity. In addition, many studies, while emphasizing bottom-up and community-based approaches, reported that social and political structure and the culture and attitudes of the community may reproduce inequality and individualism (Bourdieu, 1984; Harriss, 2002; Mansuri & Rao, 2004), pointing out conceptual conflicts between the so-called CBD principles.

In order to contribute toward filling this gap, in this article, we develop and apply an analytical framework in order to better understand and compare five different cases of community-based development in Iran. We ask two related research questions: First, what are the similar roles played by outsiders in relatively successful community-based development in Iran? Second, what are the variations between cases, and how they can be explained with regard to the local context and the extent to which outsiders play these roles?

The remainder of the article is organized as follows. The next section reviews the literature on CBD and roles of outsiders. Section 3 presents the methodology and case studies. Sections 4 and 5 then present and discuss the results for the research questions. Section 6 concludes with some general observations and suggestions for future research.

Community-Based Development and the Role of Outsiders: A Review of the Literature and Analytical Framework

CBD and CBOs

Community-based and participatory development approaches emerged as a response to the drawbacks of top-down development interventions pursued by national governments or international organizations (Mansuri & Rao, 2004). As a response to these challenges, community-based and -driven approaches were developed which are based on community collective action and participation as the main agent of changeFootnote 3 (Bhattacharyya, 2004; Mansuri & Rao, 2004; Mathie & Cunningham, 2003; McLeroy et al., 2003). They mainly adopt an ‘engaged epistemology’ in which the ‘community-based interventions emerge from the reality that has been, and continues to be, constructed and enacted by the members of a community’ (Murphy, 2014, p.7). This participation takes place in institutional entities called CBOs, which consist of organized community members who voluntarily lead the process. The CBOs are either informal or legally registered, and may traditionally exist in the community or may be created intentionally by the outsiders (Mansuri & Rao, 2013).

CBOs may play different roles in the development process depending on their individual theories of change; however, there are some similar core functions. As Aiken et al. (2016) find in their study, CBOs contribute to development processes under six main headings (p.1680): ‘helping to build community identity and cohesion; enhancing community capacity; enhancing democratic voice; improving service delivery; developing the mission; contributing to community sustainability.’ The CBO provides a vital space for enabling constructive and innovative interactions among people (this concept is also mentioned by other authors using terms such as ‘liminal space’ [Watkins & Schulman, 2008] and ‘liquid networks’ [Johnson, 2011]). This space is crucial for encouraging everyone to express and appreciate different views—reflecting on the situation with a broader perspective, and enabling creativity and innovation. The CBO is the institution whereby people organize themselves and mobilize their common resources toward the development goals. In addition to solving problems, they help to create a ‘new spirit of solidarity’ among members of the community (Murphy, 2014), enhancing their self-confidence and growing their knowledge and skills by letting them try to learn by doing. Finally, as an institution, the CBO embeds developmental practices inside the community, making them more sustainable (Ibid).

Roles of Outsiders in CBD

As described in the introduction, the lack of self-confidence, hope, and shared mentality of passiveness and neediness—together with the fading of productive social bonds and local structures—have made the role of the outsiders in CBD in Iran more prominent, at least at the starting point of the change process. It is also clear that certain institutional voids are hard if not impossible to fill without outside help, e.g., improving state-community accountability relations, accessing market research and information, product distribution, micro-financing, and professional training and education (Jütting, 2003). Also, community-based development interventions by outsiders seem promising as they may help overcome the ‘poverty trap,’ which makes it hard for poor people to change their situations and make appropriate decisions for their long-term visions, investments, and education (Mullainathan & Shafir, 2013). In all these cases, outsiders try to take on the role of catalysts for removing obstacles and triggering indigenous actions for CBD. In the community-based approach, the outsiders only try to find some key leverage points which enable the internal processes of development inside the community, avoiding imposing the development agenda from outside. The concept of intervention is used as Long and Long (1992) describe it, i.e., as an ‘ongoing, socially constructed and negotiated process’ (p. 35) that brings out the obstacles to and triggers of productive internal mechanisms.

We can classify the main roles mentioned in the CBD literature for outsiders in three categories. First are the roles related to preparing the ground and increasing readiness in the community. This includes reaching a better understanding of the community’s history, assets, and social structures and then building the rapport with the local community needed for future relationships (Israel et al., 1998; Merzel & D’Afflitti, 2003; Frank & Smith, 1999; Mathie & Cunningham, 2003; McLeroy et al., 2003; Chambers, 1994, 2004). Then, the intervening actor may provide the primary accumulation of financial, social, and knowledge capital crucial for participation and the development process (Emery & Flora, 2006; Fifka et al., 2016; Frank & Smith, 1999; Gandy et al., 2016; Kilpatrick et al., 2003; Mathie & Cunningham, 2003; Putnam et al., 1993).

The second category comprises the roles related to the creation and/or reinforcement of CBOs’ capacities that enable them to take on the responsibility of the process (Mathie & Cunningham, 2003; Merzel & D’Afflitti, 2003; Murphy, 2014). These roles are vital, as the rest of the process takes place inside the CBO with the community’s participation.

Third are the roles related to making useful linkages between the CBOs and outside actors. Communications and networks are crucial not only inside the community, but also with external actors who own the resources of power, money, information, and service—sometimes called bridging social capital (Kilpatrick et al., 2003). According to Mosse and Lewis (2006) and Mosse (2005), development represents the result of interactions between heterogeneous actors undertaken through the institutional ‘translation’ process facilitated by ‘brokers’ who operate at the interfaces of different world views and knowledge systems. Indeed, the practitioner can work as an ally, a representative, a spokesperson, or even a political activist who advocates for the rights of the local community vis-à-vis the state (Toomey, 2009) or vis-à-vis private-sector firms to reconsider their business conduct with respect to governance, employee treatment, environmental protection, and community involvement (Fifka et al., 2016). The outsider(s) may try to enhance the internal and interactive capacities of both –the state or local government and the CBOs—as vital prerequisites for more synergistic relationships between them (Bergh, 2010), e.g., by facilitating mutual trust, offering incentives to participate, removing bureaucratic obstacles in the public sector, managing conflicts, and coordinating networks and partnerships (Aldaba, 2002). The outsider can also work as a market broker who fosters business relationships to help the local community—in the form of CBOs and cooperatives—to reach relevant markets (Eftekhari et al., 2007).

Despite the three similar roles of outsiders in CBD interventions, different activities may be fulfilled under each role corresponding to different strategies of intervention and ideal-types (Díaz-Albertini, 1991). They may differ with regard to their legal organization status, financial structure, sectoral focus, and the functions they carry out (Fifka et al., 2016). Some organizations accord significant roles to outsiders—such as financing, determination of methods, prescription of frameworks and goals, and fostering internal leaders (Mansuri & Rao, 2004). On the other hand, many outsiders limit themselves to creating capacities for public participation and supporting the main agents of development (i.e., local community members) to identify their own ideas and talents as well as enhancing their skills and relationships (Frank & Smith, 1999; Mathie & Cunningham, 2003; Murphy, 2014; Rosato, 2015). In this study, we try to learn more about these different intervention strategies and the roles of outsiders.

Methodology and Data

The multiple case study research method was used to explore the roles of outsiders in community-based development practices in Iran. In order to develop the current research questions and identify the country’s successful case studies, we interviewed experts and activists who had written about the history of development programs in Iran and their consequences, and others who know well the active groups and NGOs in the recent wave of CBD in the country (eight interviews in total). Seventeen potential local development case studies were then reviewed, of which we selected five as most suitable for this study. This selection was done by identifying relatively successful cases of people’s participation in local development according to two main criteria: first, there had to be at least one formal or informal CBO as the main agent of change during the program. Second, this CBO should have been active for at least three years after (financial) support from the outsiders ended.

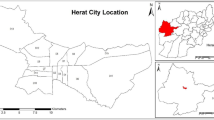

We tried to select diverse cases in terms of intervention objectives and methods, as each case can represent a wide range of similar practices in the country. Three interventions are still ongoing (numbers 1, 2, 3), while in the other two cases (4 and 5) the intervention ended but the outsiders maintain informal relationships with the CBOs. The cases are selected from five different provinces of Iran but are mostly located in the dry areas of the country’s eastern half (see Fig. 1).

Table 2 gives an overview of the case studies. In each case, relevant documents such as annual reports, progress monitoring reports, and evaluations as well as websites related to the interventions were reviewed (a full list of primary data is available from the authors). This was complemented by 15 in-depth semi-structured interviews by the first author (excluding the first eight interviewees) with two key “outsider” practitioners involved in each intervention, as well as a key member of the CBO. The interviewed practitioners were selected by their organizations as very well informed, in each case one of them being the national manager, and the other one the local practitioner. All the interviews took place between May and September 2018 in Persian. The interview guide was developed based on the literature review on community-based development and the role of outsiders. Using different sources—documents, practitioners, and community members—enabled us to triangulate the data. Between the interviews, findings from the preceding one were coded so that any gaps could be filled or ambiguous information corroborated in the next one. After coding all 15 interviews and the relevant documents, some degree of saturation was achieved—meaning that no new themes (‘sub-roles’ or ‘properties’) were added as a result of the last interviews.

The data were analyzed through the qualitative thematic analysis method (Braun & Clarke, 2006). This method enabled us to summarize the whole body of data and develop our own framework to represent various roles of the outsiders in one view (second research question). Also, it complemented the comparative multiple case study method in finding the similarities and differences among the studied cases by exploring the themes and codes. Using this method, all the interviews were transcribed and coded together in Microsoft Excel with other data extracted from the relevant documents and websites. The main text, the primary codes, and the final codes were inserted in the first, second, and third columns of the Excel datasheet, respectively. Then, overarching themes were extracted from a related set of final codes—reported as ‘sub-roles.’ After that, we searched through the codes under each theme to find its defining ‘properties.’ Also, under each of the properties the primary codes were compared, showing the variations (‘ranges’) across case studies and, in the final step, explaining the consistent properties under the specific ‘intervention strategies.’

In order to validate the findings, we undertook ‘respondent validation’ (Bryman, 2016) by sending a draft version of this article, in Persian, to the interviewees through WhatsApp or email. They were asked for their feedback in writing or by phone. As a result, seven key respondents who represent all five cases read the findings and replied. Their feedback resulted in minor corrections to the findings.

Due to time and resource constraints, the first author conducted more interviews with practitioners than with CBO members. Hence, the latters’ perspective might not be represented fully in our findings. Moreover, as we only considered the role of the interviewees in CBD as the selection criterion, their demographic diversity (age, gender, education level, etc.) were not included in our criteria nor in the analysis. However, all of them were male, Farsi-speaking, and Muslim. We were also unable to deploy more time-intensive anthropological methods such as participant observation to study each case in more depth. The thematic analysis method, although well suited to our aims, was still highly dependent on our primary framework and did not allow us to perform deep analytics of the language used (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Furthermore, the whole coding process was carried out by the first author alone (though supervised by the third author), which may impact the validity of the findings somewhat. Nevertheless, given the authors’ intimate knowledge of CBD in Iran due to their past experience working in the NGO sector, we believe that the findings are sufficiently grounded in empirical reality.

Roles and Activities by Outsiders in CBD Interventions: Findings from the Case Studies

In this section, we will answer the first research question about the extent to which outsiders play the roles mentioned in the literature in successful CBD interventions in Iran, and give some examples of these roles. Then, we briefly describe each case study to demonstrate the differences between their intervention strategies and relate them to the local context and the extent to which outsiders play different roles (thereby addressing the second research question).

Similar Roles

We analyzed the data from the case studies using the thematic analysis method and classified them according to the three main types of role developed in the previous section. The results are presented in Table 3. From this table, it is evident that the main roles in our analytical framework derived from the literature correspond to the themes explored in our analysis. As all the cases studied here adopt a community-based approach, they are very similar regarding the main roles of the outsiders: they communicate well to return a sense of agency to the community, provide similar types of primary resources (knowledge and financial), offer motivations for participation and cooperation, and facilitate relationships with the external environment.

Under the first role, there was consensus between the interviewees from different cases about the importance of building trustful relationships with the local elders and officials, and communications to change mindsets (about the opportunities and/or root causes of issues). The outsiders tried to return motivation, hope, and sense of identity to the local communities in the first place, preparing them psychologically to take on the development responsibility. Also, it was necessary to find some financial solutions to start the required funding to define new projects and implement actions. Moreover, training in basic technical skills and consulting on their businesses and projects formed part of all the studied cases (except one), and were undertaken by the outsiders at the early stages of intervention.

After preparing the ground, in all the cases, CBOs were created or reinforced to take their place at the head of the development process. The outsiders may have provided incentives or described the benefits in running the CBOs, and facilitated the interactions inside them. In most cases, existing collective activities and social capital had declined and needed new triggers from the outsiders to build them up again. In all the cases, the local leaders were recognized as such (intentionally or unintentionally) and took on important responsibilities in the process of running the CBO.

And in their third role, all the outsiders tried to forge valuable connections between the local community and outside, especially the market and the state. The outsiders, as development brokers, own political, business, legal, and media knowledge and linkages that facilitated the implementation of decisions made by the CBOs.

Different Intervention Strategies and Activities

Despite all the general similarities between the five studied CBD cases, our thematic analysis also identified considerable differences. Significantly different activities in each case are demonstrated in Table 4 under each sub-role. In order to enable a better understanding of the cases, we add here a short description of each.

The Abolhassani Tribal Confederacy is a small community of 12 tribes in an area remote from the capital of its province that has successfully retained its tribal and nomadic structure and traditional livelihoods based on animal husbandry. There is a traditional natural resource management (NRM) system in the area, which is governed by the Council of Elders. For example, they decide on the size of the herds and when and where they should be brought for pasture. An NGO called Cenesta (as the outsider) has helped to legally register this traditional Council as the Council of Sustainable Livelihood (Sabetian, 2015) in which the board members include the tribe elders -who are traditionally all male- and the general assembly consists of the male and female elders of all subsidiary tribes. The intervention strategy is thus based on the belief that reviving local knowledge and NRM systems, and recognizing and formalizing them, is sufficient to lead to positive change rather than technical training and consultation from outside. For example, the external practitioners helped the locally created initiatives for resisting drought and for adaptive agriculture to be documented and presented in international conferences and exhibitions, which achieved some awards and grants for the village. Given the strong collective ethos in the community, the award money is always placed in a common fund—as happened with the prize received from the Paul K. Feyerabend Foundation in 2014 and the grant from UN GEF (Global Environment Facility) Small Grants Programme in 2010. Some other examples of the rich local heritage in Abolhassani include the traditional tribal organizing system, the local irrigation systems, technologies for storing water, the knowledge to deal with drought through suitable cropping patterns, local planning for the sustainable pasture of animals, and indigenous rangeland conservation.

Also, the practitioners facilitated the creation of associations for the local tribes (e.g., the Union of Indigenous Nomadic Tribes of Iran—UNINOMAD) and held workshops allowing the elders of the tribes to discuss their issues and let their voices be heard in public meetings with different stakeholders from the government. The outsider thus made no effort to impose any organizational structure, knowledge, or technology on the community.

This case is also a good example of relying on existing leaders and social structures in forming the CBO and facilitating its work in a well-functioning community. Such arrangements ‘challenge many Western and donor notions of “good governance” and the predominantly negative view of “elite capture”’ (Bergh, 2004, p.785). As one of the local members of Abolhassani (C1) tribe told us,

Leadership of the tribe and solving the problems and issues have been the task of our ancestors for 300 years and they led well … and during all this period and before that … we are proud that when any conflicts occur inside the tribe, we do not refer them to the police or the court, but they come to our house and my father who is the tribe elder ... to resolve it … and this is not only in our tribe ….

Also, he told us about the reason he put the total amount of the prize in the common fund:

[The works and benefits] definitely can’t be non-collective [and captured by only one individual] … if I want all the benefits for myself … I can get rich very soon. But our ancestors never did so and wanted everyone to grow with each other. We are always happy and live comfortabl[y] and in welfare only if the whole tribe is healthy and in welfare. If there is a benefit, it reaches everyone … It is true that some activities can be done better individually … but when the benefits are for all it is better. When the Abolhassani involves 300 households [it] is a better place to live than only with my own family.

In Basfar, the outsider was a national NGO called the Young Farmers Club. The intervention strategy pursued by the outsider was to convince the local youths to establish a CBO for their village in order to reflect on the current status in their region, the underlying reasons for it, and how they can change it. The primary core membership of the CBO were young men which was then extended to a more diverse population in age and gender (now about 100 out of 150 members are female). The external practitioners made them more aware of their lawful rights to establish a legal CBO (registered as an NGO)—in the name of the Young Farmers Club—which could enter into collaborations with public-sector organizations. They guided them about what opportunities exist in public organizations to absorb funds and services (such as job training and marketing) and how they can advocate for their rights effectively, and helped them to create a network and find the right contact points inside the state bureaucracy. The practitioners did not bring any money to the Club, but helped its members identify and access relevant governmental resources. Strong relationships were established in the local community with the local government and with other villages that have such clubs, to allow them to pursue their demands in a broader coalition.

The Club undertook a comprehensive assessment of the history, issues, resources, and available opportunities in the village. The NGO did not direct the Club members toward certain issues or solutions, but shared with them its own past experiences from other rural clubs and different agricultural methods. The members established various working groups inside the Club, focusing on culture, sports, and entrepreneurship, and engaged new members of the community in each area.

In Golbaf, a consortium of NGOs and private companies called Resalat Social Development Network (as the outsider) is collaborating to provide strong platforms for value-chain management for the micro-production (mainly clothing, meat, and dairy products) undertaken by local households. The consortium started the collective work in the region by establishing a CBO called the Social Cooperative ClubFootnote 4 with the help of community headmen, which made financial cooperation possible. The platforms cover all the requirements including raw material supply, banking and financing, distribution to retailers or online sales, and on-the-job training for local people. Some talented local individuals were identified who took on total responsibility to recommend and teach others how to use the platforms. The outsiders only connect with the community through these local leaders.

We try to take on the local social activists as facilitators. … the key for success in Golbaf was finding that person there … God has placed these people everywhere; some compassionate, faithful, committed, concerned, disciplined persons and who have a business sense … The officials knew him well and introduced him … they told us: ‘Aha … that person is exactly the one you are looking for!’ (RN2, Interview)

As part of the intervention model, all of the production activities happen in another special form of club called the Work and Life Clubs—each one specializing in one area of production. The whole structure (including the CBOs and the outside actors) is designed so that it has become self-sufficient and covers its expenses now after several years—using the concept of social entrepreneurship. In other words, the households sell their own goods in the online marketplace and pay the outside providers for the overheads and services.

Regarding the gender diversity in this case, the Clubs contain an almost equal share of men and women—e.g., in the cloth-making Club, women are in the majority and in the Club working with animal husbandry, all are men. The two local leaders in this case are both male, however, the interviewees claimed that the leaders are always identified by the local community and in many of their interventions in other areas they are female.

This case represents a systematic solution to the institutional void in many rural areas in Iran. The outsiders believe that in a limited-timeframe project, merely psychological empowerment and the creation of CBOs are not enough for local development interventions, and that there is a need to retain connections with outside value-chains. This intervention strategy is illustrated by the following quote:

If you look at many empowerment cases in Iran, they only produce jams, dolls, and at most some different agricultural crops which mostly fail to sell due to market fluctuations … But we are providing a value chain … and if we go away someday, at least the villager has work skills, has production technology which is her own … and it does not mean that she is dependent on us, and we have been cautious about not making this person our worker. She buys the raw material and sells the products and so on and we only provide the infrastructure for that. (RN1, Interview)

In Lazour, the development project was run by the local government organizations (specifically the county branch of the Forests, Range and Watershed Management Organization) with support from the UNDP (United Nations Development Programme) and the national state. The intervention strategy by the outsider, as part of the local government, was to make participation possible for everyone including the local community and local government members. A couple of strong and democratic participative structures were formed by the local community—and with the outsider’s facilitation—including the Coordination Council, which is a body consisting of about 86 members—of which about 15 were female- elected by the whole community to decide on local issues and their solutions. They were encouraged to speak about anything that they thought was their issue using the Participatory Rural Appraisal (PRA) methods and techniques (Chambers, 1994).

Describing our aims and goals honestly is the key to entering the village. In Iran we cannot wander in[to] the village at first; they would ask, ‘who is he?’ And they get skeptical of you and maybe they fear you. So it is better that you introduce yourself and your goals to get them to trust you and explain your benefits for them. By benefits, I do not mean constructing dams, qanats,Footnote 5 or giving loans, etc. … I did not say I have money and facilities. I only said I can help you organize your minds and develop action plans with each other. If you do not want that, I will go away! … Then we start with facilitation methods to get them speaking and ask them good questions … Building trust is not a technique but a behavioral relation. … you only have to be patient. (FO1, Interview)

Council members then came up with some important projects and organized the local workers to implement them. These projects included constructing a detention dam for preventing floods and using water more effectively, building storage for animal fodder, canal linings, and planting trees to protect the land. A CBO called the Central Core, consisting of seven members—including two females- is responsible for the practicalities of the projects such as analyzing the problems, writing proposals, and following up on the decisions of the Council in terms of implementation. In most cases, the Central Core even carried out the technical and constructional designs of the projects, although recently the official Rural CouncilFootnote 6 has mostly taken on these tasks and the Core is not working anymore. There are also some Workgroups, consisting of key local stakeholders, focusing on important subjects in particular areas, like agriculture and animal husbandry. The outsiders coordinated the public organizations to support these projects, including budget and on-demand technical advice and training for their design and constructions.

And finally, in Mohammadabad Paskouh, the intervention strategy was to establish two micro-funds -one for men and the other for women- pooled by local community members and outsiders, and to provide low-cost and group-credit loans to improve household livelihoods. The outsider is Abrar Charity Society, a national NGO established and funded by the Iran Chamber of Commerce, Industries, Mines and Agriculture (ICCIMA), which works as an intermediary between governmental organizations and the local communities to make sure the money is spent on its intended objectives. For this purpose, in Mohammadabad, a CBO called Planning and Supervision Headquarters was established, consisting of the main male actors from the local community, to decide who is eligible for the government’s entrepreneurial loans. Moreover, there are some associations for special products like carpet weaving and clothing which were empowered by training courses for women held by the outsider. Abrar supported the associations with technical training and product marketing. Besides the entrepreneurial loans, some cost-sharing infrastructural projects were also accomplished—such as planting trees throughout the residential areas, replacing the traditional fuels (bush and wood) that destroyed the rangelands with fossil fuels, and establishing a garbage collection system. Most of these projects were decided upon in the General Assembly of the village, which traditionally came together at the local mosque.

Having briefly presented the five case studies and the role of outsiders in them, the following section discusses and explains the similarities and differences between them.

Discussion

In order to explain the roles of outsiders in CBD interventions in the five case studies, we have to take both the similarities shown in Table 3 and different activities in Table 4 into account. In congruence with our literature review, we consider the three similar roles as the core of the CBD interventions and attribute different activities under each role to various strategies of intervention under CBD. Therefore, we summarize these roles and activities as demonstrated in Fig. 2 and discuss them here.

Preparing the Ground and Increasing Readiness to Start the Process

Our analysis shows that the more self-identity, agency, and self-confidence are weakened in the community as a result of past top-down development programs, out-migration of the productive human capital, and the dissipation of local knowledge, the more necessary it is to initially arrange triggering activities. Our findings show that these issues are prominent in many of the local areas in Iran. This role in general consists of communication and dialogue with local community members in order to empower them psychologically and enhance their mental readiness for the process. We see this, for example, in Golbaf, among the studied cases in which rapid urbanization and several failed projects had taken place in the past and the outsider took great pains to rebuild trust and confidence among the members that development was possible by internal agency. These dialogues bore fruit in all cases—initially through the outsiders and the community headmen, and then with the public, the elders, or the youth depending on the CBO structure and community leaders (more discussion follows in our account of the second role).

Furthermore, the outsiders took action to accumulate internal financial capital, externally donated capital, and/or state budgets in order to invest in primary projects or lending to community members to form their own businesses. In addition, in some cases technical skills and knowledge as a requirement for development were provided on-demand or as a condition of receiving further services from outside (more discussion on the financial support and knowledge training follow can be found below).

Primary Organizing for Development Based on the Community (CBOs)

In all of our cases, the CBOs were similarly at the center of the development process enabling community members to participate and mobilize their capital. However, they differed regarding their structures. In the case of Abolhassani, the development process was built on the community’s strong traditional social systems and know-how, and the existing norms of cooperation and collaboration, without the need to create a new CBO structure. Here, the role of the outsider lay in documenting the indigenous heritage, especially the local knowledge and social systems, and in making them recognized and appreciated by officials and international development organizations. The outsider recognized the social structure and internal leaders, and identified them to the relevant national and international organizations in order to gain legal and financial support. Indeed, our data show that the ‘modern’ organizational governance functions that the outsider had tried to impose on the CBO—such as political bargaining and democratic decision-making in annual general meetings—had proved significantly less durable than the community’s traditionally known social practices.

Conversely, in cases where social bonds had weakened or serious conflicts arisen over time, the outsiders tried to establish new structures. This made it possible to consider the interests and benefits of all community member groups in decision-making. For example, in Golbaf and Basfar, the outsiders had proposed a specific pre-determined structure for the CBOs, as a first best solution to establish an organization. Further, in the case of Lazour, with its multiple detached clans, the outsider encouraged the community to create democratic structures and engage in inclusive discussions, which resulted in participative agenda-setting and the definition of public projects.

Regardless of any potential CBO structure, local leaders play an eminent role in Iranian culture. Hence, they were actively present in all of our cases. In Abolhassani, the leaders were simply found at the head of the tribal hierarchy and they were already organizing the CBO. Also, it is important that these leaders have the ability to mobilize and encourage most members of the community and to be passionate enough about their hometown development. For example, in the case of Basfar, although the intervention strategy was well realized and the youth were successfully empowered and mobilized, because the CBO did not engage with the key influencing members of the community, the traditional community would not follow the young members of the CBO in initiating change in the area.

Finding these talented individuals and assigning them as local practitioners may also have important implications for the sustainability of CBD practices. The outsiders who deal with limitations in their capital and timeframe inevitably cannot stay forever and take care of the CBOs. This often results in less-frequent meetings and activities inside the CBOs. In two of our cases (Lazour and Mohammadabad Paskouh) in which the intervention was in the ‘project’ format, we see that CBO activities have decreased considerably over time after the outsiders’ exit. This shortcoming was addressed in the case of Golbaf by delegating the process ownership to skillful resident leaders while the outsiders actively explored for local talented individuals and engaged them to take responsibility for the process leadership.

Taking on the Role of Brokers Who Bridge the Gap Between the Local Community and Outside Institutions (and Sometimes Build Appropriate Institutions)

The outsiders practiced different activities under this role, such as mobilizing external resources, advocating for rights, making meta-regional coalitions, bureaucratic facilitating, and elaborating and providing access to national and international value-chains and market information. Our cases show that in rural Iran this role of bridging gaps and building institutions is more crucial than the others because changing institutional voids create a need for greater levels of effort, resources, and power than a local community alone can mobilize from within itself. Nevertheless, this bridging/building role is less emphasized in CBD literature and practices, in which development solutions are sought mostly just in the arenas of local participation and community agency.

Our cases show that it can even be necessary for outsiders to retain this role for years. In all of our cases, some forms of relationship—formal or informal—are still present between the community and the practitioners. However, only in Golbaf does the outsider declare this as part of its intervention strategy—and in Lazour, Basfar, and Abolhassani, the outside practitioners continue helping the communities informally to improve their relationships with public and international organizations.

Although it makes sense in the short term, in order to make development sustainable, organic relationships (access to value-chains, local government, finance, etc.) have to be established between the community and outside actors over time. In Basfar and Abolhassani, the outsiders took steps to legalize the CBO and empower the community politically to advocate for its own rights. The outsiders asserted that they had never spent their own money on the project, but had simply made the communities aware of public and international grants and loans and helped them in receiving them. In Basfar, this resulted in robust connections with the local government—so much so that the youth of the CBO are now even collaborating in regional governance. On the other hand, in Lazour and Mohammadabad Paskouh, the community members whom we interviewed regretted the fact that they had not taken the opportunity to mobilize more external support before the ending of the project. As a result, the CBOs that were known as the decision-makers on how to assign the outsiders’ budget are now losing their existential role. This once again demonstrates the challenges facing the ‘project’ mode of development. Even in Golbaf, despite the fact that the relationship is retained as part of its explicit model and the financial element is sustained by the idea of social enterprise, a significant burden is placed on the outsiders’ platforms, overloading the outsiders and causing dependencies and bureaucratic inefficiencies.

Conclusion

In this article, we have studied five different cases which illustrate the recent wave of community-based development in Iran. The initial review of the literature revealed three main types of role fulfilled by outsiders to support the indigenous processes run by a community: preparing the ground and increasing readiness, the creation and/or reinforcement of CBOs, and making useful linkages between the CBOs and outside actors. Our analysis corroborates these three roles by identifying the main root development issues that can be addressed by outsider interventions: lack of self-confidence and hopelessness, lack of a minimum stock of capital to start the process, degraded institutions of cooperation, and lack of access to outside institutions.

Some typologies have already been proposed for development and outsider practices in general (Eyben et al., 2008; Fifka et al., 2016), but this study shows that different intervention strategies are also possible under the CBD approach. Therefore, despite the three so-called similar roles indicating the community-based nature of interventions, noticeably different strategies and activities under each role were also explored among the case studies. In Fig. 2, these similarities and differences are shown.

The history of development practices in the region, the existing level of local knowledge and functioning social structures, the presence of de facto leaders in development processes, and the level of organic access to outside institutions are some of the determining contextual factors that correspond with specific intervention strategies under CBD. The differences in the context tell us whether we would be better off making primary communication with public or with community leaders, training in technical skills or utilizing local knowledge, creating new structures or seizing traditional ones, exploring new talents or engaging existing leaders, and deciding when to exit or to continue relationships with the local community. These different strategies show that the concept of community-based development approaches is not as simple or uniform in successful practice as it is described in some theoretical texts (Bhattacharyya, 2004; Frank & Smith, 1999; Mathie & Cunningham, 2003; McLeroy et al., 2003; Murphy, 2014). Recognizing this variation broadens our understanding of CBD practices and helps practitioners think about alternative perspectives and approaches in order to make better decisions according to the local context.

One implication of this study for policy-makers and development practitioners is that they first have to understand and recognize the existing local systems and knowledge. If such considerable capitals are still functioning in the community, we move away from technical training and building new (democratic) structures and start the development program by building on the current capitals and improving them. Also, it is important to make connections with community leaders and give them roles in the CBD program. In cases where we do not reach the existing leaders, we first need to explore leadership talent in public communications and prepare that leadership to take on responsibility. We also learned that developing outside relationships is no less important than internal development in terms of community agency and participation. This is what ‘project’-like practices—in which the outsiders plan to build the CBO and supply financials and training, and then exit in a specific time span—often fail to take into account. Our results show that the decision to stay or exit is, again, context-based and depends on the level of established connections with political bureaucracies and business value-chains, and it may not result in leaving—even for many years. However, this does not negate the crucial task of outsiders to establish organic external connections.

Yet, we believe that this study is only the first step toward recognizing the diversity among CBD interventions. We suggest that future research be undertaken to test and evaluate the proposed intervention strategies in response to contextual factors. Furthermore, it would be useful to look at different intervention strategies from the grassroots perspective, i.e., to extend the study of these cases in order to bring out to a greater degree local people’s own perceptions and interpretations about the participatory nature and developmental impact of such interventions. Moreover, given the importance of the central government in Iran, more research should be done on the role of the national administration and its relations with intervention organizations and CBOs.

Notes

According to the UNDP Human Development Report website (http://hdr.undp.org/en/countries/profiles/IRN, Retrieved in August 2020), 100% of the country’s rural population has access to electricity; the mortality rate attributed to unsafe water, sanitation, and hygiene services is 1.0 per 100,000 population; and 70% of the population use the internet, while mobile phone subscription is 100%. No less than 85.5% of adults are literate and the expected years of schooling total 14.7, almost equally among women and men.

The recent approach can be called the third wave of nationwide local development in Iran. Before that, the first wave occurred during the first years of the Islamic Revolution, the imposed Iran-Iraq war, and volunteer activities in rural areas in the so-called Jahad-e Sazandegi movement, which was also encouraged by the Islamic government as a sacred action of helping others and constructing the country. The second wave occurred in congruence with the global participatory trend, the environmental movement (as it is called by Fadaee, 2011). It originated as a political movement started by the reformists after they had attained the presidency, and mostly by the country’s educated youth who were seeking new values and more social freedom and political change (Ibid). As a result, from 1997 to 2005, the number of environmental NGOs increased countrywide from 20 to 640 (Ibid). Such groups were not limited to environmental areas, but also worked on other social issues. These NGOs were also empowered by support from international organizations (such as the UNDP) which preferred neither direct nor state intervention in the country, but offered supporting grants to third sectors for development activities.

‘Community-based development’ (CBD) has been used in a broader sense in any project in which beneficiaries are actively participating, and ‘community-driven development’ is more specifically used to express the fact that the control of authority is given to the local community (Mansuri & Rao, 2004). We use the term CBD in this article as it is more common in the literature and projects.

This club, in the Resalat model of intervention, is a group of local people who come together in order to help each other—especially by lending money or pooling their financial resources.

A qanāt, or kārīz, is a gently sloping underground channel to transport water from an aquifer or water well to the surface for irrigation and drinking (Wikipedia).

Rural councils are democratic structures inside the villages of Iran as part of the local government structures. However, they are often not very active in terms of promoting local development.

References

Aiken, M., Taylor, M., & Moran, R. (2016). Always look a gift horse in the mouth: Community organisations controlling assets. Voluntas International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 27(4), 1669–1693.

Aldaba, F. T. (2002). Philippine NGOs and multistakeholder partnerships: Three case studies. Voluntas International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 13(2), 179–192.

Amiri, M., Pourmousavi, S. M., & Sadeghi, M. (2014). An Investigation into social harms originating in squatter settlement in the district 19 of Tehran municipality from urban managers’ perspective. Journal of Urban Economics and Management, 2(5), 119–137. (In Persian).

Anbari, M. (2016). Nightmare of ‘development’ and rural disquiet. Social Studies and Researches in Iran., 5(1), 171–187. (In Persian).

Aref, F., Redzuan, M. R., & Emby, Z. (2009). Assessing community leadership factor in community capacity building in tourism development: A case study of Shiraz. Iran. Journal of Human Ecology, 28(3), 171–176.

Azkia, M., and Ghaffari, G. (2004). Rural Development with an Emphasis on Iranian Rural Society, Nashre Ney, Tehran. (In Persian)

Barimani, F., Jalalian, H., Riyahi, V., & Mehralitabar, M. (2016). Examining the efficiency of community-based financial organizations on socio-economic development: The case of rural areas of Babol. Sociology of Social Institutions, 3(2), 195–228. (In Persian).

Bergh, S. I. (2004). Democratic decentralisation and local participation: A review of recent research. Development in Practice, 14(6), 780–790.

Bergh, S. I. (2010). Assessing the scope for partnerships between local governments and community-based organizations: findings from rural Morocco. International Journal of Public Administration, 33(12–13), 740–751.

Bhattacharyya, J. (2004). Theorizing community development. Community Development, 34(2), 5–34.

Bourdieu, P. (1984). Distinction: A social critique of the judgment of taste (R. Nice, Trans.), Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101.

Bryman, A. (2016). Social research methods. Oxford University Press.

Chambers, R. (1994). Participatory rural appraisal (PRA): Challenges, potentials and paradigm. World Development, 22(10), 1437–1454.

Chambers, R. (2004). Ideas for development: Reflecting forwards. IDS Working Paper 238, Institute of Development Studies, Brighton, Sussex, UK.

Dadvar-Khani, F. (2012). Participation of rural community and tourism development in Iran. Community Development, 43(2), 259–277.

Díaz-Albertini, J. (1991). Non-government development organisations and the grassroots in Peru. Voluntas International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 2(1), 26–57.

Eftekhari, A. R., Sadjasi Qidari, H., & Eynali, J. (2007). A new perspective to rural management with an emphasis on influencing institutions. Village and Development, 10(2), 1–30. (In Persian).

Emery, M., & Flora, C. (2006). Spiraling-up: Mapping community transformation with community capitals framework. Community Development, 37(1), 19–35.

Eyben, R., Kabeer, N., & Cornwall, A. (2008). Conceptualising empowerment and the implications for pro-poor growth: A paper for the DAC poverty network. Institute of Development Studies.

Fadaee, S. (2011). Environmental movements in Iran: application of the new social movement theory in the non-European context. Social Change, 41(1), 79–96.

Farhadi, M. (2008). Vara: An introduction to anthropology and sociology of co- operation and participation. Sahami Enteshar. (In Persian).

Fifka, M. S., Kühn, A. L., Adaui, C. R. L., & Stiglbauer, M. (2016). Promoting development in weak institutional environments: The understanding and transmission of sustainability by NGOs in Latin America. Voluntas International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 27(3), 1091–1122.

Firouzabadi, A., & Jafari, M. (2016). The study of indigenous and religion-based NGOs’ capabilities to resolve the forthcoming challenges of the development of rural, community-based areas (Case Study: Ebad Theologue Jihadi Group). Journal of Islamic Iranian Pattern of Progress Model, 4(1), 153–173. (In Persian).

Frank, F., & Smith, A. (1999). The community development handbook. Human Resources Development Canada.

Gandy, K., King, K., Streeter Hurle, P., Bustin, C., & Glazebrook, K. (2016). Poverty and decision-making: How behavioural science can improve opportunity in the UK, The Behavioural Insights Team (BIT).

Harriss, J. (2002). Depoliticizing Development: The World Bank and Social Capital. Anthem Press.

Hesamian, F., Etemad, G., and Haeri, M. (2005). Urbanization in Iran, Agah, Tehran. (In Persian)

Iran Planning and Budget Organization (2017). An analysis on National Population and Housing Census in 2016, Tehran. (In Persian)

Israel, B. A., Schulz, A. J., Parker, E. A., & Becker, A. B. (1998). Review of community-based research: Assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annual Review of Public Health, 19(1), 173–202.

Jalili Kamju, S., & Nademi, Y. (2019). Evaluation of the relationship between underground water resources extraction and rural poverty in Iran. Journal of Economic Research, 54(3), 525–550. (In Persian).

Johnson, S. (2011). Where good ideas come from: The natural history of innovation (1st Riverhead trade (pbk). Riverhead Books.

Jütting, J. (2003). Institutions and development: A critical review. OECD Development Centre Working Paper No. 210, OECD Publishing, Paris.

Kamali, B. (2007). Critical reflections on participatory action research for rural development in Iran. Action Research, 5(2), 103–122.

Katouzian, M. A. (1974). Land reform in Iran a case study in the political economy of social engineering. Journal of Peasant Studies, 1(2), 220–239.

Kilpatrick, S., Field, J., & Falk, I. (2003). Social capital: An analytical tool for exploring lifelong learning and community development. British Educational Research Journal, 29(3), 417–433.

Kolahi, M., Moriya, K., Sakai, T., Khosrojerdi, E., & Etemad, V. (2014). Introduction of participatory conservation in Iran: Case study of the rural communities’ perspectives in Khojir National Park. International Journal of Environmental Research, 8(4), 913–930.

Long, N., & Long, A. (Eds.). (1992). Battlefields of knowledge: the interlocking of theory and practice in social research and development. Routledge.

Majd, M. G. (1987). Land reform policies in Iran. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 69(4), 843–848.

Mansuri, G., & Rao, V. (2004). Community-based and-driven development: A critical review. World Bank Research Observer, 19(1), 1–39.

Mansuri, G., & Rao, V. (2013). Localizing development: Does participation work? World Bank.

Mathie, A., & Cunningham, G. (2003). From clients to citizens: Asset-based community development as a strategy for community-driven development. Development in Practice, 13(5), 474–486.

McLeroy, K. R., Norton, B. L., Kegler, M. C., Burdine, J. N., & Sumaya, C. V. (2003). Community-based interventions. American Journal of Public Health, 93(4), 529–533.

Merzel, C., & D’Afflitti, J. (2003). Reconsidering community-based health promotion: Promise, performance, and potential. American Journal of Public Health, 93(4), 557–574.

Mosse, D. (2005). Cultivating development: An ethnography of aid policy and practice (anthropology, culture, and society). Pluto Press.

Mosse, D., & Lewis, D. (2006). Theoretical approaches to brokerage and translation in development. In D. Mosse & D. Lewis (Eds.), Development brokers and translators: The ethnography of aid and agencies (pp. 1–26). Kumarian Press Inc, West Hartford.

Mullainathan, S., & Shafir, E. (2013). Scarcity: Why having too little means so much, time books. Henry Holt & Company LLC.

Murphy, J. W. (2014). Community-based interventions: Philosophy and action. Springer Science & Business Media.

Putnam, R. D., Leonardi, R., & Nanetti, R. Y. (1993). Making democracy work: Civic traditions in modern Italy. Princeton University Press.

Rafipoor, F. (1997). Modernization and conflict: An attempt toward the analysis. Sahami Enteshar. (In Persian).

Rafipoor, F. (2014). Darigh Ast Iran ke Viran Shavad, Sahami Enteshar, Tehran. (In Persian).

Rezvani, M. R., Badri, A., Salmani, M., & Qarani Arani, B. (2009). Analyzing Effective factors on participatory rural development model (case study: Hableh River Catchment Area). Human Geography Research Quarterly, 42(4), 67–86. (In Persian).

Rosato, M. (2015). A framework and methodology for differentiating community intervention forms in global health. Community Development Journal, 50(2), 244–263.

Sabetian, F. (2015). Community governance and Livelihood assessment report for Abolhassani Tribal Confederacy, Centre for Sustainable Development and Environment (Cenesta), Tehran.

Toomey, A. H. (2009). Empowerment and disempowerment in community development practice: Eight roles practitioners play. Community Development Journal, 46(2), 181–195.

Watkins, M., & Shulman, H. (2008). Toward psychologies of liberation. Palgrave Macmillan.

Acknowledgements

The first author would like to acknowledge the support of the International Institute of Social Studies (ISS) at the Erasmus University Rotterdam in hosting him as a visiting researcher from November 2018 to March 2019, and thank the members of the Civic Innovation Research Group for their useful suggestions and feedback on the initial ideas for this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Naficy, A., Bergh, S.I., Akhavan Alavi, S.H. et al. Understanding the Role of Outsiders in Community-Based Development Interventions: A Framework with Findings from Iran. Voluntas 32, 830–845 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-021-00339-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-021-00339-5

symbol)

symbol)