Abstract

Civil society strengthening programs aim to foster democratic governance by supporting civil society organization (CSO) engagement in advocacy. However, critics claim that these programs foster apolitical and professional organizations that have weak political effects because they do not mobilize citizen participation. This literature focuses on how donor programs lead to low legitimacy of CSOs with citizens, limiting the means to develop agency toward the state. Here I investigate the influence of CSO legitimacy with donors and citizens on civic agency. Empirical research was conducted in Bosnia–Herzegovina on CSOs considered legitimate by donors, citizens, and both. I found that different forms of legitimacy were associated with different strategies and agency. CSOs with both forms of legitimacy, which have not received much attention until now, turned out to be of particular interest. These CSOs demonstrated agency as intermediaries between donors, government, and citizens, which enabled greater agency and broader outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

International donor agencies frequently provide support to civil society (CS) because they expect that the result will be to foster democratic governance by enabling the representation of interests and holding elected officials accountable (Diamond 1994; Ottaway and Carothers 2000). The literature on these CS strengthening programs, however, has highlighted their rather weak effects on governance (Belloni 2001; Harriss 2001; Pouligny 2005; Suleiman 2012). A critique argues that the lack of theorized effects on governance is because donors are essentially looking in the wrong place; CS strengthening has focused on ‘professional’ non-governmental organizations (NGOs) while overlooking grassroots, traditional interest groups and non-formal forms of CS (Chahim and Prakash 2014; Howell and Pearce 2001; Kostovicova 2010). CSOs from the overlooked group, such as unions and cooperatives with a grassroots focus and membership base, are being crowded out by foreign-funded organizations (Chahim and Prakash 2014; Howell and Pearce 2000). The approach to change favored by donors is ineffective because it emphasizes foreign expertise over local knowledge (Fagan 2008; Pouligny 2005). Donor bias in favor of technocratic, professional, and apolitical NGOs is seen to have reduced CS to a technical exercise (Bebbington et al. 2008; Harriss 2001; Pouligny 2005) and to focus the supported organizations on rendering services rather than fostering society–state relations (Verkoren and van Leeuwen 2012).

The conclusion regarding the apolitical organizations that result from donor support is that do not engage in political approaches to achieving their goals. Based on this literature on CS strengthening programs, we expect that donor-supported civil society organizations (CSOs) would have limited ‘civic agency’ (Fowler and Biekart 2013) toward the state. By civic agency, I mean the capacity and actions to influence laws and policies on behalf of constituents.

The literature has increasingly addressed the issue of legitimacy in explaining that donor-supported CSOs do not typically engage in political approaches to achieve their goals because they lack the means. That is because donor-supported CSOs are often not accepted by citizens. A lack of legitimacy in the eyes of citizens reduces the ability of these CSOs to engage in political mobilization and citizen participation, even though such activities are a key theoretical mechanism for impacting democratic governance (Diamond 1994; Verkoren and van Leeuwen 2014; White 2004). The availability of donor funding leads to the creation of new CSOs with little local backing. These organizations are accountable primarily to donors, not citizens. In addition, initiatives in which citizens unite for social or political change either receive little assistance or ‘NGO-ize’ in order to become eligible for funding, leading to a growing distance from their constituency (Bebbington et al. 2008; Chahim and Prakash 2014; Hilhorst 2003; Suleiman 2012). The local legitimacy of CSOs is central to these arguments, focusing as they do on the weak connections of donor-supported CSOs to local constituencies.

The critique also draws conclusions about which CSOs are considered legitimate with donors, namely, those that are professional, technocratic, and apolitical. However, this existing research on CS strengthening emphasizes the CSOs supported by donors, while much less research has addressed the CSOs without donor support. Due to this selection bias, the ability of the existing research to draw conclusions about the impact of local versus donor legitimacy, or a lack thereof, is limited. This study addresses this gap by selecting CSOs with variations in their forms of legitimacy—those that have high legitimacy with donors but not citizens (‘donor darlings’), those that have high legitimacy with citizens but not donors, and those that have high legitimacy with both citizens and donors. This provides a more solid base from which to understand the effects of both forms of legitimacy, as well as their combined effect (following Verba et al. 1994).

This article will thus address the research question ‘How do CSO legitimacy with donors and citizens influence civic agency and outcomes in the presence of donor CS strengthening programs?’ In order to do so, empirical research was conducted in Bosnia–Herzegovina (Bosnia). Bosnia is an instructive case because the recovery from the 1992–1995 war in the immediate aftermath of the cold war meant that it was a major focus of donor attention as few other countries in the world. CS strengthening formed a core of these efforts and the literature on Bosnian CS echoes key elements of the critiques of CS strengthening programs described above (Belloni 2001, 2007; Fagan 2005). Even more than 20 years later, Bosnia remains in fifth place among democracies for the most donor aid per capita (Center for Systemic Peace 2017; World Bank 2017). As a result, the effects of donor aid might be more pronounced, making Bosnia an extreme and, therefore, an instructive case regarding CS strengthening programs (Yin 2003).

By illuminating the separate and combined effects of both donors and citizens as sources of CSO legitimacy, the research adds empirical data to the literature on CS strengthening programs. I show how different types of CSO legitimacy can be used to help understand their civic agency or lack thereof. My findings suggest that the critiques articulated above need to be nuanced. For one thing, where other publications suggest that local and donor legitimacy are mutually exclusive, I detected CSOs that combine both forms of legitimacy, which appears to enhance their civic agency. Second, I found that, in contrast with Western CS literature, in a context like Bosnia, informal ties to political actors—which below will be called ‘transactional capacities’—often lead to more civic agency than the ability to mobilize citizens—or ‘participatory capacities.’ Third, my findings suggest that some forms of expertise can be relevant for civic agency but that donors and politicians have quite different understandings of professionalism and expertise.

This article will first elaborate on the literature referred to above regarding CSO legitimacy and its influence on civic agency. Next, it will discuss the methodology that was used. Each of the three categories of CSOs, defined by variations in legitimacy with citizens and donors, will be described and illustrated with a case study. A final section makes the arguments introduced above based on the differences in civic agency between the legitimacy categories.

CSO Legitimacy and Its Influence on Advocacy Roles

This section will begin by defining CSO legitimacy and justifying the relevance of my approach to the study of donor and citizen legitimacy. Next, the literature on CSO legitimacy in Bosnia is examined. Then, civic agency is defined and operationalized, also in relation to the theoretical distinction between participatory capacity and transactional capacity. This section will conclude with a diagram of the concepts and relationships present in the research question.

Understanding CSO Legitimacy

Organizational legitimacy has been most elaborated in the neo-institutionalism school, according to which legitimacy derives from an organization’s environment (Brinkerhoff 2005, p. 5). A CSO’s legitimacy can be defined as ‘a generalized perception or assumption that the actions of an entity are desirable, proper, or appropriate within some socially constructed system of norms, values, beliefs and definitions’ (Suchman 1995, p. 574). Legitimacy arises via intersubjective processes of ‘legitimation’ in which CSOs make claims of legitimacy and come to be considered appropriate and trustworthy (Hilhorst 2003, p. 4). Although legitimacy is based in subjective perceptions, its consequences are tangible, generating material and other resources and affecting the functioning of organizations. The critiques of CS strengthening programs described earlier focus on the perspectives of citizens and donors as key actors whose perceptions can ‘legitimate’ an organization.

The literature on CS strengthening programs has frequently put donor-sponsored organizations in one category and grassroots and traditional organizations in another distinct and mutually exclusive category (Chahim and Prakash 2014; Pouligny 2005; Verkoren and van Leeuwen 2014). Some studies on Bosnia support the idea that organizations with local legitimacy are not the same as those considered legitimate by donors (Belloni 2001; Pupavac 2005). However, only a few studies exist regarding local opinions on CSOs. The findings of these studies are that citizens prefer organizations offering direct ‘help’, such as social services and humanitarian aid (Grødeland 2006; Pickering 2006). On the other hand, mobilization and ‘political activities’ are seen negatively (Helms 2014), probably because politics itself is tainted by conflict and corruption. Citizens also have critical opinions about donor programs. Citizens often assess donor programs based on whether they ‘solve concrete problems’, and their skepticism about donors’ normative frameworks and results contribute to the dearth of CSOs enjoying legitimacy for both groups. However, earlier research by this author found that the combination of legitimacy with donors and citizens is possible (Puljek-Shank and Verkoren 2017). We will return to this below.

Civic Agency: Participatory or Transactional Capacities?

Civic agency is adopted here in order to consider whether and under what conditions CS actors do demonstrate the agency that is theoretically assigned to CS. This is agency with the ability to limit state power, provide alternative channels for representing interests, and strengthen state–society relations (Diamond 1994; White 2004). This is, after all, what CS strengthening programs have aimed to achieve. Civic agency in its simplest form is concerned with agency on behalf of groups toward the state. For the reproducibility and analytical clarity of this research, a precise definition of civic agency is needed. In fact, agency itself can be challenging to operationalize. As put by Long, ‘Agency is usually recognized ex post facto through its acknowledged or presumed effects’ (2001, p. 240). To address this difficulty, civic agency was defined as ‘the perception of capacity, and action to create change for a common good’, leading to operationalization based on the capacities and actions.

‘Common good’ describes the desired outcomes of civic agency on behalf of a group. The theory regarding the enhancing effect of CSOs as alternative channels for representing interests (Diamond 1994; White 2004), and facilitating and enhancing collective action (Ostrom 2015), concerns this ability of CSOs to achieve desired outcomes by representing a group of constituents vis-à-vis the state. A common good is thus not a partial or club good that only benefits its contributing members (Olson 1971; Welzel et al. 2005). Common goods are, however, public goods, subject to the ‘free-rider problem’ and the dynamics of individual collective action (Olson 1971). Common good is used rather than public good because public good refers to both those that ‘can only be defined with respect to some specific group’ as well as those available to all citizens (Olson 1971, p. 14). Common good is also used because CSOs representing their members’ interests can also do so at the expense of the public good writ large (Gugerty and Reynolds 2010). Perceptions of capacities are included based on the idea that actors can only be said to have civic agency if they perceive that they can influence other actors in their environment. The following section will examine two distinct forms of capacity from theory and empirical research.

Because of their ability to politically mobilize citizens to a variety of actions under the rubric of participation, CSOs are frequently considered relevant for governance both in theory and by donors. A theoretical link between CSOs and their ability to mobilize political participation has a rich history leading back to de Tocqueville (2002) and the early wave of neo-Tocquevillian scholars (Diamond 1994; Putnam 1992; White 2004). This tradition identifies the effects of CSOs on democratic governance due to limiting state power and providing alternative non-electoral channels for representing interests (Diamond 1994). CSOs have also been found to facilitate and enhance collective action at a local scale (Ostrom 2015). Participatory democracy theory connects participation with greater levels of political efficacy (Montoute 2016). This is because participation increases citizens’ political awareness, increases efficacy and empowerment, and promotes a more equal and more stable society (Hilmer 2010; Montoute 2016). However, many critiques of CS strengthening programs conclude that these outcomes rarely happen due to the low legitimacy of donor-supported CSOs with citizens. These debates regarding the participatory effects of CSOs on governance in democratizing polities are also reflected in the literature on the experiences of post-Communist Europe (Crotty 2003; Ost 2005; Raiser et al. 2001). Howard’s (2003) study, for example, made the case that persistent low levels of CSO membership, an indicator of low legitimacy with citizens, were the cause of the ‘weakness of civil society’.

The thesis that CSO impact derives primarily from its ability to mobilize participation, however, has been challenged by scholarship, which finds that these low levels of CSO membership and individual participation do not inherently limit CSO capacities and efficacy. This literature argues that individual participation or ‘participatory activism’ should be complemented by ‘transactional activism’, i.e., ‘ties—enduring and temporary—among organized nonstate actors and between them and political parties, power holders, and other institutions’ (Petrova and Tarrow 2007, p. 79). Participatory activism includes electoral and contentious politics, interest group activities, and—more broadly—individual and group participation in civic life. Transactional activism describes the observed salience of linkages to authorities that facilitate negotiation related to activists’ goals. It is transactional in that strategic networking and problem-solving with authorities are used to achieve desired ends. Its proponents do not dispute the weakening effects of low CSO membership; rather they claim that the transactional character of activism merits attention due its implications for the potential of negotiation with the state and elites (Cox 2012; Petrova and Tarrow 2007; Puljek-Shank 2017). This literature sees the relevance in whether CSOs possess the ‘resources and skills to gain a voice in the public sphere’ (Rikmann and Keedus 2013, p. 161). Finally, a transactional approach is of interest because CSOs have been found to have influence to the extent that they bring resources lacking but sought by states (Fagan 2010, p. 73; Montoute 2016). As a result, these dynamics regarding capacities might have broader applicability regarding the impact of CS strengthening programs on governance in other democratizing polities. To summarize, there are reasons to consider the civic agency of CSOs from both participatory and transactional perspectives.

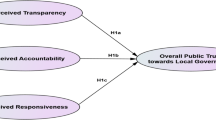

The concepts examined in this research are represented in Fig. 1. The civic agency of CSOs, positioned centrally, is the phenomenon being investigated. The diagram includes three types of actors—political actors, citizens, and donors. Transactional capacity is diagrammed with a dashed bi-directional arrow indicating the participation of both political actors and CSOs. Participatory capacity is diagrammed with a directional dashed arrow indicating the ability of CSOs to mobilize citizens. The independent variables are the two sources of legitimacy, legitimacy with donors and citizens. The remainder of the article will address the separate and combined effects of legitimacy with donors and citizens on capacities and civic agency.

Methodology

The first step was to map CSOs from three focus areas of youth, women, and social welfare. The focus areas were chosen as marginalized groups,Footnote 1 which are both objects of international CS strengthening efforts and also have potential local constituencies (Belloni and Hemmer 2010; European Commission 2005; EVS 2010). CSOs with high and low legitimacy were initially identified via interviews with key informants who were selected to represent diverse and socially significant perspectives.Footnote 2 The use of unlikely conditions to test a theory, such as considering marginalized groups to understand the emergence of civic agency, has been called Sinatra-inference (i.e., ‘if it can make it here, it can make it anywhere’) (Levy 2008, p. 12).

I selected those CSOs that could be assigned to one of three categories based on combinations of legitimacy with donors and citizens, as indicated in Table 1. CSOs were selected if there were multiple consistent mentions by key informants as described above, and by a cumulative assessment of multiple indicators (see Table 2). The relatively objective indicators for constituency support were used to confirm the legitimacy or lack thereof for parts of the population (i.e., becoming a member, providing financial support, and/or volunteering are actions taken by the population that indicate legitimacy).

Next, a list of advocacy initiatives with political goals was composed for each of the 27 selected CSOs based on document analysis and an initial interview with the CSO leadership. Advocacy is used here to mean any actions to influence the state. This includes both actions intended to mobilize citizen participation (e.g., protest, participation in consultations) as well as those conducted directly with political actors and bureaucrats (e.g., lobbying, use of expertise, convening state agencies). Advocacy strategies were identified based on the coding of the staff interviews and documents. Although the literature includes linkages between different categories of CSOs as transactional capacity (Petrova and Tarrow 2007), these were coded as participatory because of their focus on horizontal ties with CSOs that enjoy legitimacy with citizens. Those strategies repeated by more than one CSO are listed in Table 3. Pearson’s Chi-squared tests of marginal independence were used to determine the association between the legitimacy variables and the application of each strategy. The differences in the incidence of specific strategies and the underlying forms of capacity (participatory or transactional) are the basis for the empirical findings. However, with few cases and the resulting low incidence values, a result of statistically significant associations between legitimacy and strategy use was only possible for five strategies.

Finally, ten of the CSOs were selected as case studies using theoretical sampling (Flick 2009) based on the three quadrants in Table 1. Each case-study organization was researched in greater depth by process tracing. Process tracing involved interviews with state and other CS actors and relevant internal and public document review. Process tracing was selected in order to examine the evidence for civic agency as a causal mechanism in contrast to the evidence that the observed outcomes were caused by the actions of other actors. While the article is based on the evidence regarding advocacy strategies for the broader group of CSOs, the case studies will be used to illustrate the observed differences in advocacy strategies.

Empirical Findings

This findings section discusses the civic agency of the three categories of CSOs. The first subsection will address the category least-commonly discussed in the literature, those having legitimacy with both donors and citizens. Each of the subsections will elaborate on the results presented in Table 3: Advocacy strategies) and Table 4: Association between legitimacy and advocacy strategies). The second and third subsections will elaborate on the impact of one form of legitimacy without the other. This enables revisiting the critiques of CS strengthening programs and drawing some conclusions regarding their impact on civic agency.

Legitimacy with Citizens and Donors

This section will discuss the CSOs that enjoy legitimacy with both citizens and donors. Compared to the other categories, these CSOs pursue broader goals to greater effect by serving as active intermediaries between donors and local actors. First, these CSOs are able to achieve these outcomes because they bring donor financial and symbolic resources. They also function as intermediaries by collaborating with other CSOs that are accepted by constituencies. Second, both collaboration and their own legitimacy with citizens strengthen their legitimacy with political actors and, therefore, their ability to achieve outcomes. In short, they can more often successfully navigate their environment in order to achieve support from both donors and diverse local actors. These dynamics are elaborated through a case study that highlights the intermediary role of CSOs with both forms of legitimacy.

This group of CSOs was able to achieve broader outcomes as measured by the degree of implementation, their longevity, and the amount of money allocated to them by the state (See Appendix B in the Supplemental Materials). This is based on the acknowledged role of CSOs from this category in passing the Federation and Republika Srpska (RS) Laws on Youth,Footnote 3 which created youth councils and led to new policies and budget allocations at the municipal and (to a varying degree) higher levels of governance. In addition, the civic agency of these CSOs led to ongoing state funding for domestic violence shelters, criminalization of domestic violence, and improved responses to victims by state institutions (United Women 2007). In contrast, the civic agency of the other categories was focused on narrower and more incremental governance goals. The other categories were also frequently only able to achieve formal but not substantive (implemented and funded) outcomes.

The combination of legitimacy with donors and citizens is associated with an increased prevalence of transactional strategies (Table 3). Both policy adoption and monitoring strategies enable engagement with the government and the potential for in-person lobbying, a form of transactional capacity that many interviewees indicated is the most effective at achieving desired outcomes (Interviews, 20 February 2013, 13 April 2013). The case studies provide evidence that this is because donor support enables financial and symbolic resources sought by political actors. Namely, donor resources are a key element of how advocacy strategies are frequently implemented. They enable the use of elegant facilities and cover lodging, travel, and food for government participants in training and consultation events. Flashy reports and strategy documents, also produced in English, reflect positively on the participating institutions. Moreover, publicity events (distributed by media that are compensated) provide exposure and political benefits to elected Sofficials (Interviews, 17 April 2013, 14 September 2012, 4 December 2013, Conference on Youth Councils, 22 April 2013). Furthermore, donor support frequently brings international diplomatic support and together with the imprimatur of international conventions provides foreign support for political narratives of progress and change. Moreover, the context of CS strengthening programs means that such trappings are common and expected, and engaging with government around goals and processes initiated by CSOs is difficult without them. Although transactional strategies are also implemented without these donor resources, they are most frequently implemented when supported by donors. The importance of the expectation created by this context will be seen in comparing this category to those CSOs that also have legitimacy with citizens but low legitimacy with donors.

In addition to the sensitivity to donor resources articulated above, political actors are also sensitive to the legitimacy of CSOs with citizens. Political actors tend to support CSO initiatives that are not just about appearances but that are also constructive and focused on results and the ‘everyday needs’ of constituencies (Interviews, 31 August 2012, 11 September 2012, 26 September 2012). They are also responsive to whether CSOs are accountable to members (Interview, 12 November 2013) and if they, in the words of a Federation Member of Parliament, ‘really represent a wider group of citizens and their interests’ (Interview, 26 September 2012).

The CSOs that enjoy legitimacy with both donors and citizens are able to function as intermediaries between donors, citizens, and the government. This function as intermediaries is partly financial, referring to the CSOs’ capabilities to receive donor funds and apply them to solving concrete needs of citizens. CSO legitimacy is relevant for this process because the CSOs in this category frequently strengthen their intermediary role through their ability to partner with organizations that enjoy high legitimacy with citizens but low legitimacy with donors. Helsinki Citizens Assembly (HCA) from Banja Luka advocates with a human rights normative framework and fits into this group. Other CSOs that have high legitimacy with citizens but low with donors indicated that the legitimacy of HCA led them to be willing to cooperate. As stated by a staff person, ‘what separates project “In” from many, many others is that it is implemented by HCA … and four high-quality partner organizations with long experience which work directly with beneficiaries. We created the program with nuances for our end beneficiaries.’ (Interview, 12 November 2013). In this way, HCA was able to advocate for the rights of the disabled by addressing the specific needs of the developmentally disabled. This is an example of a partnership between ‘intermediary’ CSOs that enjoy support with donors and citizens and ‘representative’ ones that enjoy legitimacy with citizens but not donors. The prevalence of such partnerships indicates the strategic way that these different kinds of CSOs approach such partnerships to advance their respective goals. The intermediaries could successfully navigate their environment in order to achieve support from both donors and diverse local actors.

The partnerships discussed above are also a way of building legitimacy with political actors. Namely, political actors perceive that collaboration between CSOs strengthens CSO legitimacy. For an official in the RS Ministry for Health and Social Welfare, ‘for a real step forward it would be much better to have an articulated, unified position, a high-quality, progressive position. Then the administration would be able to take it more seriously’ (Interview, 12 November 2013). The CSOs in this group function as ‘intermediaries’ by the way that they strategically foster and utilize trusting relationships with other CSOs as a way to legitimate themselves with political actors.

The ways that CSOs utilize both forms of legitimacy will be illustrated through the youth CSO KULT. KULT is a professionalized and large organization by Bosnian standards, occupying a spacious house in the Sarajevo outskirts of Ilidza. It emerged from student organizing and more specifically frustrations with the politicized student union. KULT conducts leadership training programs, capacity building for youth CSOs, policy advocacy at the Federation and national levels, and runs a municipal youth center. Its staff claimed to have helped draft and pass the Federation Law on Youth, a contribution recognized by others. The youth councils created by the law were represented as evidence that KULT worked toward and achieved empowerment for youth. As stated by a staff person, ‘now government can’t say that they don’t have an equal partner to talk to’ (Interview, 31 March 2013). The salience of this claim in the legitimation of KULT was demonstrated when others referenced their important role in convening and training the youth councils as a reason for KULT’s legitimacy. In the words of KULT staff, ‘only youth know what they need’. In a KULT-organized conference, presentations by youth council representatives from three cities provided indications of the participatory capacity of the councils with young citizens in that they were able to mobilize to attend municipal assembly and planning meetings. These councils also demonstrated civic agency in that they were able to overturn funding reductions and had leverage in negotiations with municipal assemblies. This civic agency was pursued for common goods, including youth centers and activities, such as language and computer classes.

To summarize the findings regarding CSOs that enjoy legitimacy with donor and citizens: they demonstrate civic agency in pursuit of broader goals and are able to more effectively pursue them by serving as active intermediaries between donors, citizens, and political interests. In order to achieve these results, they use transactional advocacy strategies, such as policy adoption and monitoring, in such a way that depends on donor resources as a means to deepen engagement with government actors and to create opportunities for personal lobbying. CSOs that enjoy legitimacy among donor and citizens also function as intermediaries by fostering partnership relationships with other CSOs and interest groups.

Legitimacy with Citizens but not Donors

This section will discuss the civic agency of those CSOs that enjoy legitimacy with citizens but not donors, beginning with an illustrative case study. These CSOs are distinguished by their more frequent application of contentious politics, their active response to participation opportunities, and in the degree to which they develop expertise relevant for advocacy. This means that their civic agency is guided by the representation of specific constituencies. However, this section will also describe how their lack of donor legitimacy limits their ability to achieve governance outcomes.

These strategies will be elaborated via the umbrella CSO MeNeRaLi. MeNeRaLi was founded in the midst of the war in 1993 and emphasize that they represent parents of developmentally disabled individuals who make up 29 local chapters across the RS. It is primarily funded by the RS government and is officially recognized via membership in an RS-level alliance of social welfare organizations. Since 2011, MeNeRaLi has focused on ‘analysis and giving concrete suggestions for social inclusion of our beneficiaries into the community through services within the social welfare system’ (Interview, 12 November 2012). During this process, the approach has been incremental, emphasizing substantive implementation of a few rights over the formal adoption of many. Its major advocacy initiatives have been related to the revision of the RS Law on Social Welfare (LSW) (Narodna Skupština RS, 2012). MeNeRaLi initially engaged in active participation regarding this revision in response to an invitation from the RS Ministry of Health and Social Welfare (Partner 2013). The following discussion of capacities will describe struggles to achieve outcomes for MeNeRaLi’s beneficiaries.

One of the most interesting differences is that this group is more willing to engage in contentious politics, even though such actions are approached carefully and strategically. For MeNeRaLi, the threat of protest was both a potent one and one not engaged in lightly. The staff first gauged support for this measure by local chapters and sought to engage other CSO allies. They gathered statements from their members indicating that the members were ready to stage public protests. In advance of a meeting with the Ministry to which the government-recognized alliances were invited, MeNeRaLi staff proposed a joint strategy and negotiating position. However, this did not yield a joint position, and in the assessment of MeNeRaLi staff, it was this lack of unity that led to failure in achieving their goals.

A second strategy that was used by these CSOs more frequently was active participation in response to participation opportunities. Active participation was coded as a strategy if the CSO responded to an invitation to participate by the government, e.g., MeNeRaLi’s response to consultations regarding the revised LSW. However, for many of the researched CSOs, government consultations are only pro-forma and do not lead to substantive outcomes; their lesson after participation was that it was a waste of time and, ‘I wouldn’t do it again’ (Interview, 13 December 2013). This indicates the way that participating CSOs weigh the required investment of time against the potential but uncertain outcomes. Given these conclusions, why do they keep engaging in these consultations? Donor material and symbolic resources that come with legitimacy among donors are what distinguish the previous ‘intermediary’ group from the ‘representatives’ described here. In the absence of opportunities, such as convening institutions or building transactional capacity, CSOs with low donor legitimacy respond to these consultations as their only option. In contrast, the ‘intermediary’ CSOs respond less to participation opportunities because they have more effective alternatives.

The final salient strategy is that these CSOs applied expertise more frequently than any other category. This is a surprise given the literature which concludes that donor support leads to a technocratic and professional approach which inhibits civic agency (e.g., Chahim and Prakash 2014; Harriss 2001; Pouligny 2005). Applying expertise refers to specialized knowledge, for example, the data that MeNeRaLi had gathered regarding their developmentally disabled beneficiaries, and which was recognized and sought-after by the government. This information increases their capacity in their own eyes because, ‘if I need something from the state it’s in my interest to have high-quality information not that of the state’ (Interview, 12 November 2012). The relevance of expertise to the ability to achieve outcomes was supported by a Federation Member of Parliament and frequent CSO ally who stated:

In a group like handicapped, for example, in which there are several problems and some come up repeatedly and they’re not addressed adequately in law and regulations, it’s important to recognize the problem and then expertly address the needs and what can be done. Expertise is important. (Interview, 26 September 2012)

The relevant expertise is focused on the specific constituencies and relevant laws and regulations. This discussion of expertise as a strategy will be continued in the next section because it is less common for the CSOs that enjoy legitimacy among donors but not citizens.

This section has indicated how the civic agency of CSOs that enjoy high legitimacy with citizens but low legitimacy with donors is characterized by the representation of specific constituencies via primarily participatory capacities. This category is distinguished by their more frequent use of contentious politics, investing time in active participation, and developing expertise that is applied in advocacy initiatives. However, this expertise is often also narrow (i.e., limited to a particular constituency and related set of policy issues). The relevance of expertise as a capacity thus supports a narrow civic agency focused on these constituencies. In addition, lacking donor financial and symbolic resources, these CSOs are less able to initiate and pursue broad advocacy goals.

Legitimacy with Donors but not Citizens

This section will address those CSOs that are legitimate with donors but not citizens. In doing so, it will return to the strategy of applying expertise, which is inhibited for this category. The reason for these varied applications of expertise will be discussed in regards to diverse understandings of expertise itself. Next, a case-study CSO will illustrate how CSOs in this category withdraw from advocacy when faced with the lack of implementation of formal outcomes. The civic agency of this category is thus primarily characterized by the pursuit of their goals through means other than advocacy, and limited rather than strengthened by their expertise.

The previous section on ‘representative’ CSOs that enjoy legitimacy with citizens but not donors discussed their more frequent strategy of applying expertise. The opposite holds for the present category—in fact, the one significant difference for this category is that they use expertise less frequently. This is a surprising result given the focus in the CS strengthening literature on their bias toward ‘professional’ and technocratic CSOs (e.g., Chahim and Prakash 2014; Pouligny 2005). The explanation is that for donors, expertise refers to project management skills, such as grant and report writing, and English language knowledge. Moreover, such skills are typically practiced by staff whose epistemological frameworks derive from practical experience, or ‘new forms’ of informal or interdisciplinary education. In contrast, the expertise applied by CSOs that have high legitimacy with citizens referred to knowledge of state policies, institutions, and how bureaucratic government systems work, with epistemological frameworks derived from formal education in traditional professions such as law and social work. These educational programs are traditional in the sense that they existed in the pre-war, Socialist period. Some examples of the latter expertise are the procedures of Parliamentary hearings and points of contradiction between different laws in the case of MeNeRaLi. Other CSOs indicated expertise in medical issues of their beneficiaries, municipal tender procedures, and the workings of municipal councils. The conclusion is that these different categories of CSO apply very different forms of expertise.

The civic agency of this category will be presented through the case-study Youth Information Agency (YIA), which was formally established in 2001 and began earlier as a spin-off organization of the foreign-funded Open Society Institute. Over this period, YIA has engaged in diverse approaches including high-level political advocacy, trained successive groups of high school youth in activism, and runs an entrepreneurship center from its office. Its program Active Youth began in 2004 with a focus on workshops and lobbying, for example by organizing public dialogs between youth and local authorities. These efforts to mobilize participation between youth and elected officials reflect the donor expectations described earlier that they would strengthen civic agency. However, more recent versions implement the youths’ priorities via fundraising from companies. The YIA has shifted its focus from advocacy because the government is inefficient and fragmented and a staff person was told by one government counterpart, ‘strategies are for drawers’ (Interview, 8 January 2014). Although YIA no longer gets involved in advocacy via strategy documents, it does work with the government on addressing ‘practical questions’, such as working with youth employment centers. The YIA case was typical of the CSOs with this combination of legitimacy whose civic agency is limited and includes a retreat from advocacy.

An initiative engaged in by YIA illustrates the relationship between forms of legitimacy and capacities. One indicator of YIA’s legitimacy for donors was that it was invited to implement a program initiated and funded by the European Union Special Representative called ‘Generation for Europe.’ The concept was to select 200 successful young professionals and provide them assistance to formulate and advocate for reform-oriented advocacy goals. This shows a common approach to creating participation opportunities in order to facilitate bottom-up change. However, YIA staff indicated that the program’s lack of legitimacy for its participants ultimately made it ineffective in achieving these goals. In their view, the participants were not motivated to significantly contribute to something they perceived as a ‘foreign story’. Ultimately, the departure of its main foreign patron led to the abrupt end of the program. Preexisting low levels of legitimacy with citizens and the perception of donor support itself contributed to the weakened civic agency because such initiatives were viewed by citizens as heavily about form, weakly representing their priorities, and not able to contribute to desired outcomes.

This section addressed those CSOs that enjoy legitimacy with donors but not citizens. They are ‘donor darlings’ in the sense that they receive a disproportionate share of donor funds at the expense of other categories, despite their lack of legitimacy with citizens (Ker-Lindsay 2013, p. 263). The explanation for the surprising finding that the use of expertise is inhibited for this category appears to lie in the different forms of expertise favored by donors and the state. While donors favor project skills, state actors favor traditional professional qualifications and expertise developed in policy arenas. The lack of legitimacy for these CSOs with citizens has led to civic agency that has withdrawn from advocacy and is limited rather than strengthened by their expertise.

Revisiting Legitimacy and Civic Agency

This section aims to connect the empirical findings with the literature and theory on the relationship between CS strengthening programs and governance. It will discuss two mechanisms in the literature that link CS strengthening programs to the weak civic agency and apolitical approaches. The first mechanism is that CS strengthening programs lead to low legitimacy with citizens, thereby inhibiting civic agency. The second mechanism is that civic agency is inhibited because donors favor technocratic and professional rather than political approaches. Next, I will discuss the relevance of CSOs’ use of both citizen participation and transactional engagement with the state for CS strengthening. This section concludes with a discussion of the contribution of legitimacy to these debates.

First, the findings support the link made in the critique of CS strengthening programs that low legitimacy with citizens is a contributing factor to the adoption of apolitical approaches by supported CSOs (Bebbington et al. 2008; Kostovicova 2010; Pouligny 2005). Indeed, the ‘donor darling’ CSOs that enjoy legitimacy with donors but not citizens tend to follow apolitical approaches. Unlike CSOs that do enjoy legitimacy with citizens, they are unable to mobilize citizen participation for government consultations or protest. Participation can be a salient capacity available to CSOs as theorized (Diamond 1994; White 2004) but with an important caveat: ‘for those CSOs with local legitimacy’.

Second, the findings question the critique of CS strengthening programs, which argues that technocratic and professional approaches inhibit civic agency (Harriss 2001; O’Brennan 2013). In this light, it is surprising that the ‘representative’ CSOs with high levels of local support and low levels of donor support use expertise the most as an advocacy strategy. As indicated in the findings, this is due to differences regarding the nature of expertise. The expertise applied by this group of CSOs is related to their ability to engage in formal state processes via an understanding of legal and administrative systems, which is strengthened by traditional professional qualifications. Expertise can be a resource by which CSOs gain influence if it is sought by the state (Fagan 2010, p. 73; Montoute 2016). Yet the expertise sought was rarely provided by the ‘donor darling’ CSOs but rather was most often by the ‘representative’ CSOs, which were the least involved in donor programs.

Legitimacy adds to the debate about CS strengthening programs for a number of reasons. First, it explains the capacities available to CSOs. The salience of legitimacy is supported by the finding that the ‘intermediary’ CSOs—those with both forms of legitimacy—employ primarily transactional capacities, which leads to broader outcomes. Second, legitimacy encompasses the influence of both endogenous and exogenous factors on governance patterns. By considering both legitimacy with donors and citizens, the findings nuance the often rather absolute conclusions that can be drawn from the literature above regarding how donor support leads to apolitical approaches (Bebbington et al. 2008; Fagan 2005; Harriss 2001).

The findings support claims that despite low participatory capacity, CSOs are also able to achieve outcomes by engaging transactional capacities (Císař 2010; Petrova and Tarrow 2007). This is relevant for the literature on CS strengthening programs because donor resources were found to enable these very transactional capacities. This effect is surprising because donors frequently imagine a direct effect of strengthening and enabling participation (Ottaway and Carothers 2000). The findings also show how donor resources over time influence the expectations of political actors regarding how advocacy happens. Namely, political actors come to expect benefits such as training away from the office, the status of foreign support, and media promotion. These benefits are what donor-supported CSOs bring to the table. Thus, the findings point to the unintended consequences of CS strengthening programs, which reinforce transactional capacities rather than participatory ones. Ultimately, donors and their CS strengthening programs also become part of patterns of governance. Instead, the participatory potential can be found with the CSOs that lack donor support.

Finally, the important role of CSOs that enjoy legitimacy with donors and citizens is surprising in the context of the critiques of CS strengthening programs which see donor legitimacy and local legitimacy in exclusive terms (e.g., Chahim and Prakash 2014; Pouligny 2005; Verkoren and van Leeuwen 2014). This group deserves additional scholarly attention because the findings support their broader civic agency and greater outcomes. These CSOs were able to go beyond the ‘invited spaces’ of existing participation mechanisms and enter ‘claimed spaces’ by creating new participation mechanisms, as in the case of the youth councils (Gaventa 2006).

Conclusion

This article adopted civic agency as a theoretical framework in order to reexamine critiques of CS strengthening programs. Civic agency was analyzed in regards to the goals selected and whether CSOs use participatory capacities oriented toward mobilizing citizens or transactional capacities, based on ties to political actors. This contributes to better understanding of how CSOs engage in advocacy, going beyond the assumptions that guide both the CS strengthening programs as well as its critique. Finally, to examine the claims of the critiques, I examined the civic agency of CSOs with permutations of legitimacy for citizens and donors. This highlights the active role of citizens as those who grant or withhold legitimacy from particular CSOs, a role rather absent in the critiques. This contributes to a better understanding of CS strengthening programs and their unintended impacts on governance.

The research found that it is the combined effects of legitimacy for donors and citizens that provides insight into the political potential and limitations of CSO advocacy in the presence of CS strengthening programs. The most interesting category is those CSOs enjoying legitimacy with both donors and citizens; their civic agency is applied for broader policy changes, such as creating new participation opportunities. Although it is largely based on ties to political actors (i.e., transactional capacity), these CSOs are also engaged in strengthening participatory ties to other CSOs, including those with different kinds of legitimacy. This combination of capacities increases their ability to be intermediaries between donor and local interests and to persist in their goals, giving them the unrecognized long-term potential to influence governance.

The civic agency of CSOs that have legitimacy with citizens but not donors can be described as a representation of constituencies. These CSOs more readily engage in participation, including protest but also consultations. However, their lack of donor support limits their goals and civic agency. In contrast, the ‘donor darlings’ enjoying legitimacy with donors but not citizens most closely resemble the apolitical NGOs frequently described in the literature. However, they surprisingly apply expertise less frequently in their advocacy, which can be explained by the fact that the expertise that they offer is considered less relevant by the state.

The findings addressing the potential results of CSO civic agency paint a picture that is more complex and less absolute than that given by the critiques of CS strengthening programs. CSOs in the two categories that enjoy legitimacy with citizens (‘intermediaries’ and ‘representatives’) demonstrate persistent civic agency in their goals and actions, and these do lead to observable outcomes. The findings also have policy relevance because current multiyear policies in Bosnia respond to the critiques by their emphasis on representation, credibility, and autonomy as necessary contributing factors for strengthening CS advocacy roles (EU DG Enlargement 2013; USAID 2013). Making decisions based on these factors, however, requires a better understanding of the views of citizens and of how donor programs themselves shape the potential of civic agency. The implication, both for policy and for further scholarship, is to pay greater attention to those CSOs that enjoy both legitimacy with donors and with citizens because of their potential to play intermediary roles.

Notes

As demonstrated by levels of employment (10.9% of youth ages 15–24 actively seeking employment and 22.7% of women vs. 31.7% of the total population) and 2011 CSO grant support for women’s CSOs (0.7% of total), youth CSOs (2.8%), and social welfare categories that included disabled and drug dependency CSOs (5.1%) (Agency for Statistics of Bosnia and Herzegovina 2014; Center for Investigative Journalism 2011). In addition, 17% of Cantonal ministers and 22% of state ministers were women (Sarajevo Open Center 2015). Within social welfare, recommended CSOs provide assistance regarding development disabilities, life-threatening diseases, and children.

Twenty-seven key informants from the following categories were included: political actors (4), religious CS (3), media and business (3), CS networks (5), international CS (2), CS Building projects (4), donors (4), and international political actors (2). Key informants were selected based on experience relating to CSOs in addition to their primary sectors, and their assessments regarded CSOs to which they did not have institutional ties to reduce potential bias.

The Federation of Bosnia-Herzegovina and RS are sub-national entities established by the Dayton Peace Agreement with considerable autonomy regarding education, social policy, and policing.

References

Agency for Statistics of Bosnia and Herzegovina. (2014). Labour force survey. Sarajevo.

Bebbington, A., Hickey, S., & Mitlin, D. (2008). Can NGOs Make a Difference: The Challenge of Development Alternatives. In A. Bebbington, S. Hickey, & D. Mitlin (Eds.), Can NGOs Make a Difference?: The Challenge of Development Alternatives (pp. 3–37). London, New York: Zed Books.

Belloni, R. (2001). Civil society and peacebuilding in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Journal of Peace Research, 38(2), 163–180. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343301038002003.

Belloni, R. (2007). State building and international intervention in Bosnia. London: Routledge.

Belloni, R., & Hemmer, B. (2010). Bosnia-Herzegovina: Civil society in a semi-protectorate. In T. Paffenholz (Ed.), Civil society and peacebuilding: a critical assessment (pp. 129–152). Boulder: Lynne Rienner.

Brinkerhoff, D. W. (2005). Organisational legitimacy, capacity and capacity development (Discussion Paper No. 58A). Washington, D.C.: RTI International.

Center for Investigative Journalism. (2011). Database for public fund allocations for nonprofit organizations and public institutions. Retrieved October 11, 2012, from http://database.cin.ba/finansiranjeudruzenja/.

Center for Systemic Peace. (2017). Polity IV annual time-series, 1800–2016. Retrieved January 1, 2017, from http://www.systemicpeace.org/inscr/p4v2016.sav.

Chahim, D., & Prakash, A. (2014). NGOization, foreign funding, and the Nicaraguan civil society. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 25(2), 487–513. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-012-9348-z.

Císař, O. (2010). Externally sponsored contention: The channelling of environmental movement organisations in the Czech Republic after the fall of communism. Environmental Politics, 19(5), 736–755.

Cox, T. (2012). Interest representation and state-society relations in East Central Europe (Aleksanteri Papers No. 2/2012). Helsinki: Kikimora Publications.

Crotty, J. (2003). Managing civil society: Democratization and the environmental movement in a Russian region. Communist and Post-Communist Studies, 36, 489–508.

Daguda, A., Mrđa, M., & Prorok, S. (2013). Annual financial reports of civil society organizations in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Sarajevo: CPCD.

de Tocqueville, A. (2002). Democracy in America. (trans: Reeve, H.). Hazelton, PA: Pennsylvania State University.

Diamond, L. (1994). Toward democratic consolidation. Journal of Democracy, 5(2), 4–17.

EU DG Enlargement. (2013). DG Enlargement Guidelines for EU support to civil society in enlargement countries, 2014–2020. Brussels: EU DG Enlargement. Retrieved from http://www.balkancsd.net/images/ELARG_Guidelines_CS_support_after_online_consultation_03072013.doc.

European Commission. (2005). Mapping Study of Non-State Actors (NSA) in Bosnia–Herzegovina. Brussels.

EVS. (2010). European Values Study 2008, 4th wave, Bosnia–Herzegovina. Cologne: GESIS Data Archive. https://doi.org/10.4232/1.10179.

Fagan, A. (2005). Civil society in Bosnia ten years after Dayton. International Peacekeeping, 12(3), 406–419.

Fagan, A. (2008). Global-local linkage in the Western Balkans: The politics of environmental capacity building in Bosnia-Herzegovina. Political Studies, 56(3), 629–652. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.2007.00711.x.

Fagan, A. (2010). Europe’s Balkan dilemma: Paths to civil society or state-building?. London: I.B. Tauris.

Flick, U. (2009). An introduction to qualitative research (4th ed.). Los Angeles: SAGE Publications Ltd.

Fowler, A., & Biekart, K. (2013). Relocating civil society in a politics of civic-driven change. Development Policy Review, 31(41), 463–483. https://doi.org/10.1111/dpr.12015.

Gaventa, J. (2006). Finding the spaces for change: A power analysis. IDS Bulletin, 37(6), 23–33. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1759-5436.2006.tb00320.x.

Greenwood, P., & Nikulin, M. (1996). A guide to Chi square testing. New York: Wiley.

Grødeland, Å. B. (2006). Public perceptions of non-governmental organisations in Serbia, Bosnia & Herzegovina, and Macedonia. Communist and Post-Communist Studies, 39(2), 221–246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.postcomstud.2006.03.002.

Gugerty, M. K., & Reynolds, T. (2010). Civil society and ethnicity. In H. Anheier, S. Toepler, & R. List (Eds.), International encyclopedia of civil society (pp. 198–203). New York: Springer.

Harriss, J. (2001). Depoliticizing development: The World Bank and Social Capital. New Delhi: Leftword Books.

Helms, E. (2014). The movementization of NGOs? Women’s organizing in postwar Bosnia–Herzegovina. In I. Grewal & V. Bernal (Eds.), Theorizing NGOs: States, feminisms, and neoliberalism (pp. 21–49). Durham, NC: Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.1111/amet.12124.

Hilhorst, D. (2003). Discourses, diversity and development: The real world of NGOs. London: Zed.

Hilmer, J. (2010). The state of participatory democratic theory. New Political Science, 32(1), 43–63.

Howard, M. M. (2003). The weakness of civil society in post-communist Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Howell, J., & Pearce, J. (2000). Civil society: Technical instrument or social force for change? In D. Lewis & T. Wallace (Eds.), New roles and relevance: Development NGOs and the challenge of change (pp. 75–88). Bloomfield, CT: Kumarian Press Inc.

Howell, J., & Pearce, J. (2001). Civil society and development: A critical exploration. Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

Ker-Lindsay, J. (2013). Conclusion. In V. Bojicic-Dzelilovic, J. Ker-Lindsay, & D. Kostovicova (Eds.), Civil society and transitions in the Western Balkans (pp. 257–264). New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Kostovicova, D. (2010). Civil society in post-conflict scenarios. In H. Anheier, S. Toepler, & R. List (Eds.), International encyclopedia of civil society (pp. 371–376). New York: Springer.

Levy, J. S. (2008). Case studies: Types, designs, and logics of inference. Conflict Management and Peace Science, 25(1), 1–18.

Long, N. (2001). Development sociology: Actor perspectives. New York: Routledge.

Montoute, A. (2016). Deliberate or emancipate? Civil society participation in Trade Policy: The Case of the CARIFORUM–EU EPA. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 27(1), 299–321. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-015-9640-9.

Narodna Skupština RS. (2012). Zakon o socijalnoj zaštiti Republike Srpske [Law on Social Welfare of the Republika Srpska]. Banja Luka.

O’Brennan, J. (2013). The European Commission, Enlargement Policy and Civil Society in the Western Balkans. In V. Bojicic-Dzelilovic, J. Ker-Lindsay, & D. Kostovicova (Eds.), Civil society and transitions in the Western Balkans (pp. 29–45). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Olson, M. (1971). The logic of collective action: Public good and the theory of groups. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Ost, D. (2005). The defeat of solidarity. Cornell: Cornell University Press.

Ostrom, E. (2015). Governing the commons: The evolution of institutions for collective action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ottaway, M., & Carothers, T. (Eds.). (2000). Funding virtue: Civil society aid and democracy promotion. Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Partner. (2013). Vijesti. Retrieved January 1, 2014, from www.ho-partner.rs.sr.

Petrova, T., & Tarrow, S. (2007). Transactional and participatory activism in the emerging European polity: The puzzle of East-Central Europe. Comparative Political Studies, 40(1), 74–94. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414006291189.

Pickering, P. M. (2006). Generating social capital for bridging ethnic divisions in the Balkans: Case studies of two Bosniak cities. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 29(1), 79–103. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870500352397.

Pouligny, B. (2005). Civil society and post-conflict peacebuilding: Ambiguities of international programmes aimed at building “New” societies. Security Dialogue, 36(4), 495–510. https://doi.org/10.1177/0967010605060448.

Puljek-Shank, R. (2017). Dead letters on a page? Civic agency and inclusive governance in neopatrimonialism. Democratization, 24(4), 670–688. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2016.1206081.

Puljek-Shank, R., & Verkoren, W. (2017). Civil society in a divided society: Linking legitimacy and ethnicness of civil society organizations in Bosnia-Herzegovina. Cooperation and Conflict, 52(2), 184–202. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010836716673088.

Pupavac, V. (2005). Empowering women? An assessment of international gender policies in Bosnia. International Peacekeeping, 12(3), 391–405. https://doi.org/10.1080/13533310500074507.

Putnam, R. (1992). Making democracy work: Civic traditions in modern Italy. Princeton N.J.: Princeton University Press.

Raiser, M., Haerpfer, C., Nowotny, T., & Wallace, C. (2001). Social capital in transition: A first look at the evidence. London: European Bank for Reconstruction and Development.

Rikmann, E., & Keedus, L. (2013). Civic sectors in transformation and beyond: Preliminaries for a comparison of six central and Eastern European Societies. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 24(1), 149–166. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-012-9305-x.

Sarajevo Open Center. (2015). Where are women in governments? (Human Rights Papers No. 11). Sarajevo.

Suchman, M. (1995). Managing legitimacy: Strategic and institutional approaches. Academy of Management Review, 20, 571–610.

Suleiman, L. (2012). The NGOs and the grand illusions of development and democracy. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 24(1), 241–261. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-012-9337-2.

United Women. (2007). Godišnji izvještaj 2007 [Annual Report 2007]. Banja Luka.

USAID. (2013). RFA: Civil society sustainability project in BiH. Sarajevo. Retrieved from http://www.grants.gov/search/search.do?mode=VIEW&oppId=227573.

Verba, S., Keohane, R. O., & King, G. (1994). Designing social inquiry: Scientific inference in qualitative research. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press.

Verkoren, W., & van Leeuwen, M. (2012). Complexities and challenges for civil society building in post-conflict settings. Journal of Peacebuilding & Development, 7(1), 81–94.

Verkoren, W., & van Leeuwen, M. (2014). Civil society in fragile contexts. In M. Kaldor & I. Rangelov (Eds.), Handbook of global security policy (pp. 463–481). Oxford: Wiley.

Welzel, C., Inglehart, R., & Deutsch, F. (2005). Social capital, voluntary associations and collective action: Which aspects of social capital have the greatest ‘civic’ payoff? Journal of Civil Society, 1(2), 121–146.

White, G. (2004). Civil society, democratization and development: Clearing the analytical ground. In P. Burnell & P. Calvert (Eds.), Civil society in democratization (pp. 6–21). London: Frank Cass.

World Bank. (2017). World development indicators. Retrieved January 1, 2017, from http://databank.worldbank.org/data/reports.aspx?source=world-development-indicators.

Yin, R. K. (2003). Case study research: Design and methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Yumasdaleni, & Jakimow, T. (2017). NGOs, ‘Straddler’ organisations and the possibilities of ‘Channelling’ in Indonesia: New possibilities for state–NGO collaboration? VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 28(3), 1015–1034. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-016-9719-y.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Fabio Andres Diaz, Ekaterina Ivanova, Steve Powell, Louis Monroy Santander, and the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments. Thank you also to Marlies Glasius, Bertjan Verbeek and Willemijn Verkoren for all of your patient assistance and to Amela Puljek-Shank for your support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Puljek-Shank, R. Civic Agency in Governance: The Role of Legitimacy with Citizens vs. Donors. Voluntas 29, 870–883 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-018-0020-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-018-0020-0