Abstract

This study examines how different types of international volunteering influence common program outcomes such as building organizational capacity, developing international relationships, and performing manual labor. Survey responses were collected from 288 development-oriented volunteer partner organizations operating in 68 countries. Data on the duration of volunteer service, the volunteers’ skill levels, and other variables were used to develop a rough typology of international volunteering. Binary logistic regression models then assessed differences in outcomes across five volunteering types. Findings suggest that future research needs to be more precise about how the nuances and complexity of diverse forms of international volunteering influence outcomes.

Résumé

La présente étude cherche à découvrir à quel point différents types de bénévolat de portée mondiale influencent les résultats de programmes courants, dont l’édification de la capacité organisationnelle, la création de relations internationales et la réalisation de travaux manuels. Un sondage a été fourni à 288 organismes bénévoles partenaires axés sur le développement œuvrant dans 68 pays. Des données sur l’ancienneté des bénévoles, leurs compétences et d’autres variables furent utilisées pour élaborer une typologie brute du bénévolat mondial. Des modèles de régression logique binaires ont ensuite évalué les écarts existants entre les résultats de cinq types de bénévolat. L’étude suggère que les recherches futures devront être plus précises quant à la façon dont les nuances et la complexité des formes variées du bénévolat mondial influencent les résultats.

Zusammenfassung

Diese Studie untersucht, wie sich unterschiedliche Arten der internationalen ehrenamtlichen Arbeit auf generelle Programmresultate auswirken, wie beispielsweise auf den Ausbau der organisatorischen Kapazität, die Entwicklung internationaler Beziehungen und die Ausführung körperlicher Arbeit. Dazu wurden die Antworten aus einer Befragung von 288 entwicklungsorientierten ehrenamtlichen Partnerorganisationen aus 68 Ländern erfasst. Man verwendete Daten zum Zeitraum der ehrenamtlichen Tätigkeit, den Fertigkeiten der Ehrenamtlichen sowie zu anderen Variablen, um einen ersten Entwurf einer Typologie zur internationalen ehrenamtlichen Arbeit zu erstellen. Mittels binär-logistischer Regressionsmodelle wurden sodann die Unterschiede zwischen den Programmresultaten für fünf Arten der ehrenamtlichen Arbeit ausgewertet. Die Ergebnisse legen nahe, dass zukünftige Studien genauer darauf eingehen müssen, wie die Nuancen und die Komplexität diverser Formen der internationlen ehrenamtlichen Arbeit die Resultate beeinflussen.

Resumen

El presente estudio examina cómo diferentes tipos de voluntariado internacional influyen en los resultados de programas comunes, tales como la creación de capacidad organizativa, el desarrollo de relaciones internacionales, y la realización de labores manuales. Se recopilaron respuestas de encuestas de 288 organizaciones socias voluntarias orientadas al desarrollo que operaban en 68 países. Los datos sobre la duración del servicio voluntario, los niveles de habilidad de los voluntarios y otras variables fueron utilizados para desarrollar una tipología aproximada del voluntariado internacional. Después, modelos de regresión logística binaria evaluaron las diferencias en los resultados con respecto a cinco tipos de voluntariado. Los hallazgos sugieren que es necesario que las investigaciones futuras sean más precisas sobre como los matices y la complejidad de diversas formas de voluntariado internacional influyen en los resultados.

Chinese

本文分析了不同类型的国际志愿者活动对普通项目效果的影响,例如,建设组织能力、发展国际关系和开展体力劳动。调查结果来自68个国家的288家发展导向型志愿者服务合作组织。有关志愿者服务期限,志愿者能力水平及其他变量的数据被用于国际志愿者服务的笼统分类。二元逻辑回归模式用于评估五种志愿者服务效果的差异。调查结果显示,未来研究国际志愿者服务多种形式的偏差和复杂性对志愿者服务效果的影响需要更加精准。

Arabic

تدرس هذه الدراسة كيف تؤثر أنواع مختلفة من التطوع الدولي على نتائج البرامج المشتركة مثل بناء القدرات التنظيمية، تطوير العلاقات الدولية، وأداء العمل اليدوي. تم تجميع الردود على إستطلاع الرأي من 288 منظمة متطوعين شريكة موجهة نحو التنمية تعمل في 68 بلد. تم إستخدام بيانات عن مدة الخدمة التطوعية، مستويات مهارة المتطوعين وغير ذلك من المتغيرات لتطوير نمط تقريبي من التطوع الدولي. ثم قامت نماذج الإنحدار اللوجستي الثنائي بتقييم الإختلافات في النتائج عبر خمسة أنواع من التطوع. تشير النتائج إلى أن البحوث المستقبلية تحتاج إلى أن تكون أكثر دقة حول كيفية تأثير الفروق الدقيقة وتعقيد أشكال متنوعة من التطوع الدولي على النتائج.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

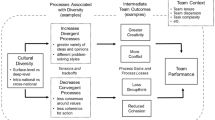

Over the past half-century, international volunteering has become a multibillion dollar industry (Adelman et al. 2016). A quick online search yields hundreds of different descriptions of opportunities for people to “give back” or participate in meaningful service in nonprofit, corporate, and governmental organizations as they volunteer abroad. In the USA alone, nearly 1 million people volunteer abroad through an organization each year (Lough 2015a). These volunteer experiences can range from short-term amateur “volunteer tourism” trips lasting only a few days or weeks to long-term skilled volunteering lasting 2 years or more (McGehee and Santos 2005; Sherraden et al. 2006). Other varieties include short-term professional volunteering or long-term volunteering by unskilled young people (Moresky et al. 2001; Simpson 2004). Nonetheless, academic and nonacademic studies often conflate diverse volunteer abroad programs, thereby making it difficult to examine how variations influence outcomes. To better understand how diverse practices may influence outcomes, we consider how differences in program factors such as service duration, skill levels of volunteers, and group size influence three separate outcomes: building organizational capacity, developing international relationships, and performing manual labor.

Several rationales underpin this study. First, only a small segment of academic scholarship on international volunteering has aimed to represent the perspectives of those who host international volunteers. Second, many existing studies investigating the effective practices of international volunteering are limited in sample size and scope or are specific to just one volunteering model. Third, much research about international volunteering tends to describe it as a rather uniform practice. While many studies may describe the context under which volunteers serve and may indicate what the volunteers do, the model of the volunteer program under research is often vague or unclear. Differences in program models complicate the clean categorization and subsequent generalizations that scholars can make about international volunteering and service (IVS). When various forms of IVS are lumped together within the same category, people can easily make incorrect assumptions and conclusions about the benefits and challenges of international volunteering.

Our motivations for launching this research project emerged from an expressed need from international volunteer cooperation organizations (IVCOs) for information to improve the effectiveness of international volunteering practices (Devereux and Mukwashi 2014; Forum 2015). Therefore, an inherent bias underlying this study is that volunteering abroad is valued and should be improved—an assumption that not all scholars and development practitioners may share (Illich 1968).

Some scholars document the utility, contributions, and positive attributes of volunteers who go abroad to share their skills and talents to less-privileged communities (Devereux 2008; Howard and Burns 2015). Other scholars raise questions about the theoretical and structural value of international volunteering—challenging assumptions about its overt value (Georgeou 2012; Heron 2007; Perold et al. 2013; Simpson 2004). While conceptual arguments advanced by these studies are valid and based on observational research, they do not always distinguish between different types of international volunteer programs and the volunteers who participate in these programs.

In broad terms, some forms of gap year volunteering or “volunteer tourism” by unskilled young people can strengthen cross-cultural communication but are also associated with a variety of poor to negative community-level outcomes including potential harm they may cause by acting on situations they do not fully understand (Graham et al. 2012; Guttentag 2009; Palacios 2010; Tiessen and Heron 2012). Likewise, research documents that “professional volunteering” by those who are highly skilled can be effective at building local capacity, producing tangible social capital, filling gaps in services, and forming sustainable development partnerships but may be less successful at developing relationships when performed over a short duration (Lough 2016a; Thomas 2001). The context of the research question is imperative. For example, if the focus of research is on how volunteering affects cross-cultural understanding and solidarity, findings may point to specific program recommendations. On the other hand, research investigating volunteers’ contributions to skills-transfers or capacity building will tell a vastly different story. Across these diverse contexts, our void in understanding about how multiple program options influence outcomes pleads for additional research. We also need a better understanding about how local development organizations negotiate challenges and limitations of hosting volunteers—particularly where the purported advantages of hosting volunteers are celebrated with little thought to programmatic and structural issues arising during volunteer placements.

This paper will assess how five different models of IVS are associated with several outcomes, thereby amplifying the voice of host organization staff to better understand how, and under what circumstances, different programs are rationalized. By linking different forms of volunteering to perceived outcomes, this study aims to provide a more nuanced of the advantages and disadvantages of the attributes that characterize diverse forms of international volunteering. Although this study can only represent a portion of the highly diverse forms and models of IVS, it provides a modest contribution to research about how these forms are associated with different outcomes.

Key Differences in Diverse Models of International Volunteering

Common variables used in previous literature to categorize IVS have been the aims of the volunteer program, the duration of service and the group size (i.e., individual vs. group volunteer placements) (Sherraden et al. 2006). Additional variables that have been used to categorize volunteering types include eligibility and participation requirements (e.g., age of volunteers, educational or technical degree requirements), reciprocal directionality (North–South, South–South, etc.), the degree of internationality (unilateral to multilateral), and the beneficiary focus (Davis Smith et al. 2005; Furco 1996; Rehberg 2005; Sherraden et al. 2006).

Goals and Aims of the Volunteer Program

The aims of volunteer programs are a primary distinguishing feature used in previous literature to categorize and separate types of IVS. Until the early 1970’s, scholarship on international volunteering primarily studied “export volunteer” placements that aimed to provide gaps in skills in developing and newly decolonized countries (Lough 2015b; Woods 1980). One notable exception was a focus on international workcamp volunteering by groups of young people, which focused on volunteers’ peace-related roles and on establishing common interests and understandings among people of different cultures (CCIVS 1984; Gillette 1968; Woods 1971). Gillette (1972) expounded on how differences between “participant-centered aims” and “society-centered aims” could distinguish goals of international volunteer programs. Andrew Furco used a similar function to distinguish between programs with a focus on the volunteer as beneficiary, and those with a focus on the hosting community or organization as beneficiary (1996). Thus, from very early in its evolution, the aims of volunteer programs were key distinguishing features separating “volunteering for development aid and humanitarian relief” and “volunteering for international understanding” (see Davis Smith et al. 2005; Sherraden et al. 2006).

Plewes and Stuart (2007) developed a third typology based on the aims of the volunteer program. Their three typologies included: (1) the “Development Model,” which aims to promote social and economic development through poverty reduction and volunteers’ contributions to diverse development goals; (2) the “Learning Model,” which focuses on developing the personal and professional skills and competencies of volunteers—particularly in relation to cultural understanding, global citizenship, and developing sympathetic future actions to support development cooperation; and (3) the “Civil Society Strengthening Model,” which aims to building democratic capacity and strengthen local civil society organizations. While this third aim certainly deserves attention, most current scholarship continues to divide volunteering models by the two broad historically relevant aims focusing on the volunteer as beneficiary and/or the community as beneficiary. There has also been an increasing emphasis in scholarly literature on reciprocal benefit, which breaks down this binary by recognizing that both parties often benefit in some way through the exchange (Lough 2016b; Stephens et al. 2015).

Within these two broad categories, scholars have proposed further subtypologies based on specific program aims. For development-focused aims, these subcategories have included volunteering for mutual aid, philanthropic volunteering, civic service, and volunteer activism and advocacy (Cronin and Perold 2008; Davis Smith 2000; McBride et al. 2003). For volunteer-focused aims, subdivisions have included areas such as volunteer tourism, cross-cultural volunteering, student volunteering/service-learning, and volunteer workcamping (Alloni et al. 2014; Coghlan 2007; Lyons and Wearing 2012; Pless and Borecká 2014).

Sherraden et al. (2006) developed a basic matrix for IVS using three main variables: program aims, duration of service, and group size. Given the limited number of variables used to describe these differences, the authors recognized this rough typology as an oversimplification of the nuanced differences among contemporary forms of international volunteering. Table 1 illustrates this early typology and includes one example of each type of volunteering occurring at the intersection of project aims, service duration, and group size.

The separation between IVS for international understanding and IVS for development aid and humanitarian relief has been described as a difference between “soft” and “hard” approaches to international understanding and development (Devereux 2008). However, this has also been noted as a false dichotomy in the minds of many volunteers and international volunteer cooperation organizations (IVCOs) that send volunteer abroad (Devereux 2010). Specifically, many development volunteers may focus on technical- and capacity-building skills but may also place a significant priority on international understanding. For instance, only one of the three goals of the US Peace Corps (categorized as IVS for development) focuses on skills-development: “Building Local Capacity.” The remaining two goals, “Sharing America with the World” and to “Bringing the World Back Home” focus on international understanding (see Peace Corps 2016)—though less diplomatic interpretations have labeled these latter two goals as imperialistic (see McBride and Daftary 2005). As indicated in Sherraden et al’s typology (2006), the intersections associated with program aims often conflate findings tied to these specific aims and suggest that additional variables beyond project aims must be considered when describing key differences in volunteer programs.

Duration of Service Abroad

Somewhat parallel to the aims of international volunteering, early scholarship on IVS studied long-term (almost exclusively 2-year), government-funded volunteer placements (Lough 2015b; Pinkau 1977; Woods 1980). Although a few scholars also investigated shorter-term workcamp placements performed by young people, no typology emerged based on volunteer placement duration (CCIVS 1984; Gillette 1968, 1972). Davis Smith et al. (2005) specified that duration of service often distinguished development aid and international understanding as the two primary goals of IVS. Sherraden et al.’s typology (2006) further separated the two historical aims into “short-term” and “medium- to long-term” categories. Short-term volunteering was defined as 1–8 weeks, medium-term as 3–6 months, and long-term volunteering as 6 months or longer (Sherraden et al. 2006).

Over the past decade, several studies have investigated the effects of service duration on the outcomes of IVS. When asking about development outcomes, host organizations have consistently asserted a preference for more experienced volunteers that can serve for longer durations (Lough 2012; Perold et al. 2013). Likewise, a number of studies point to potential asymmetries and problems associated with shorter-term placements, particularly because tourism (cultural, educational, and\or adventure) has been increasingly conflated with volunteering abroad (Georgeou 2012; Perold et al. 2013; Power 2007; Simpson 2004; Tiessen and Heron 2012). On the other hand, among volunteer programs with an intensive skills-sharing mission, short-term volunteers have been found to be quite effective (Lough 2016a).

Much of the criticism for short-term volunteering are based on studies using samples of young international volunteers (Diprose 2012; Lyons et al. 2012; Simpson 2004; Tiessen and Heron 2012). Opportunities for students to learn abroad have expanded beyond university-based study abroad options. Students now engage in short-term volunteering to receive full or partial academic credit. Such opportunities are linked to perceived benefits in career development and resume building for students in a wide range of programs (e.g., medicine, social work, and international development studies.), and the scholarship has not done enough to disaggregate the diverse options available to students, including volunteer abroad programs primarily geared to promote learning goals (Perold et al. 2013; Tiessen and Huish 2014). Learning models are frequently part of youth-oriented educational components preparing youth for working in a global context where cross-cultural adaptation is important, or as an extension of education programs to give student real-world exposure to cross-cultural differences (Jones 2005).

Measuring the effectiveness of IVS on the part of the international volunteers is linked to the depth of cross-cultural engagement and strong interpersonal relationships formed (Tiessen 2017). The duration of an international experience has been correlated with the development of long-term relationships with foreign nationals (Dwyer 2004), and previous studies point to more than 6 months as a minimum preferred duration because of the value placed on “getting to know the person” and meaningful cross-cultural encounters (CVO 2007; Tiessen 2017; Watts 2002). On the other hand, some studies point to evidence that even short-term volunteer tourism has the potential to build relationships between volunteers and host communities (Broad 2003; Singh 2002; Wearing and McGehee 2013). Alternative models of interaction also challenge the assumption that length of duration abroad is linked to lasting and meaningful relationships. Social media connections, continued e-volunteering, and other forms of ongoing interactions with volunteer partner organizations and host communities can also facilitate this deeper relationship formation (Wearing and McGehee 2013).

Research on the relational component further suggests that shorter-term professional volunteers can be particularly effective if they make multiple trips and have continued and sustained engagement in the same communities over the course of a few years (Lough 2016a; Sykes 2014). However, questions remain about a “revolving door” approach to sending different volunteers each time, even when these volunteers serve in a sustained project in the same community. Volunteering partner organizations invest a great deal of time in the preparation and acclimatization of volunteers in placements, and rapid rotation and turn-over of these volunteers can significantly affect the productivity and satisfaction of local staff (Tiessen 2017).

Individual Versus Group Volunteering

In comparison with group-based volunteer tourism, very little empirical research has compared IVS outcomes by individuals and groups. Comparative research on international volunteering for development has typically focused exclusively on individual volunteer placements. Group-based, or workcamp, volunteering commonly involves teams of 10–16 young people from multiple countries that live and work together while completing some form of work project (Sherraden et al. 2006). Another popular format includes groups of volunteers from a single-country traveling to volunteer for short periods (Coghlan 2007; Sin 2009; Tomazos and Cooper 2012). Group-based volunteering has historically been common in global responses to humanitarian and crisis situations (Lough 2015b).

Because multinational groups of typically young people serve together, the model is often dedicated to accomplishing aims of international understanding (Sherraden et al. 2006; Woods 1980). These models often focus less on volunteer-host interactions and more on the interactions between volunteers, which may build cross-cultural understanding among volunteers but may potentially inhibit cross-cultural understanding with host communities (Sherraden et al. 2008; Tiessen 2017). Likewise, when young people from the same cultural background travel in groups, this often presents challenges with developing deep cross-cultural engagement (Ogden 2008). Volunteer partner organizations have also noted a group mentality whereby the volunteers experience and come to “know” the host country by processing cultural differences exclusively within the group of visiting volunteers (Tiessen 2017). Programs that ensure regular interaction between volunteers and host communities likely make the difference. When volunteers travel as a group but spend their day-to-day activities with host organization staff, they may build meaningful relationships over the short term. However, when they have little overlap with host organization staff, the development of relationships is unlikely.

Recent research with workcamp volunteers composed of multinational teams of volunteers engaging in international projects suggests that cultural openness is enhanced among participants (Volpini 2016), though without comparison with individual volunteer placements. Group-based placements may be effective at completing projects that require manual labor (i.e., building a school, planting trees, and cleaning up beaches.)—as this is the goal of many group-based volunteer placements. However, this does not take into account broader questions such as whether manual labor skills are needed given the often high under-employment of local laborers in low-income countries (Perold et al. 2011). Overall, more research is needed to understand the impact of group dynamics on outcomes such as capacity building and international understanding between volunteers and their host communities.

Age, Education and Skill Requirements

Volunteer characteristics such as age, education level, and skills are core considerations across the diverse range of volunteer abroad program selection criteria. Some IVCOs have minimal requirements for accepting or mobilizing volunteers along individual characteristics. For instance, youth-based programs typically have both minimum and maximum age qualifications but are less concerned about educational, skills, or training requirements. On the other hand, volunteer programs for development often require volunteers to have a university degree or a professional skill set and may sometimes require prior experience abroad. These programs are growing alongside a trend for older adults volunteering abroad in the USA and the UK—and likely other high-income countries (Lough and Xiang 2016; Percival 2009). Program-level requirements set by some IVCOs may also be used to distinguish and classify types of volunteer programs. As suggested, however, these variables are generally correlated with program aims.

Additional Differentiating Variables

Other variables that have been used to differentiate volunteer programs include the type of organization (public, nonprofit, corporate, and faith based, etc.), primary funding sources used to fund volunteer initiatives abroad (i.e., public, private, and membership-based contributions.), whether volunteer partner organizations in the host countries receive or expend resources to host international volunteers, the directionality of volunteer mobilization (South–North, South–South, etc.), and the degree of internationality (single country, multinational teams, etc.) (Hills and Mahmud 2007; Sherraden et al. 2006, 2008). Although there are likely measurable differences in program outcomes by these categories and may be important variables for future research, they are not used to further subdivide our analysis in this study.

Aims and Hypotheses

As evident in the review of literature and previous research, individual and institutional variables associated with diverse volunteer models will influence their effectiveness at achieving various outcomes. We first aim to differentiate volunteer types based on reported differences in qualities such as duration of volunteer service; the skill, education, and age levels required of volunteers by hosting organizations; the volunteers’ “competency fit” with host organizations; and the respondents’ perceived level of volunteers’ motivations. We then assess the relationships between the discrete volunteer types that emerge from this initial analysis and three different outcomes: (1) developing capacity in the organization, (2) performing manual labor, and (3) developing international relationships.

A few assumptions precede this analysis. The first assumption is that skills and competencies are needed to build organizational capacity or the “intentional and planned development of an increase in skills or knowledge–allowing organizations to fulfill their mission in the most effective and productive manner” (Bentrim and Henning 2016, p. 43). A second assumption is that specialized skills are rarely required to be effective at performing the types of manual labor performed by volunteers. A third assumption is that a longer duration and repeat interaction are needed to effectively develop relationships.

In consideration of these assumptions and in combination with prior research findings, we propose and assess the following three hypotheses in this study.

Hypothesis 1

All forms of skilled volunteering will be more effective than unskilled volunteering at strengthening organizational capacity

Hypothesis 2

All forms of longer-term volunteering will be more effective that short-term volunteering at building relationships with local respondents.

Hypothesis 3

All types of volunteers will be equally effective at performing manual labor.

Skilled volunteering refers to voluntary action by people with specialized training in a particular field, and typically involves using work-related knowledge, expertise, and competencies to accomplish goals of the placement (Brayley et al. 2014). In contrast, unskilled volunteering refers to volunteer action from people who are still learning and developing the knowledge, skills, and competencies they may need for future work.

Methods

This study followed a cross-sectional research design, analyzing primary survey data collected from volunteer partner organizations (VPOs) in the low-income countries that hosted international volunteers. The study was supported by a grant from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC) to understand effective practices in international volunteering.

Participants

To gain access to the VPOs, the researchers collaborated with six international volunteer service networks (IVSNs) comprised of supranational organizations dedicated to sending volunteer abroad (see Sherraden et al. 2006), and their member international volunteer cooperation organizations (IVCOs) operating from high-income countries. The participating IVSNs were headquartered in Canada (a global consortium), the USA, Germany, Italy, and Ireland—with members spread across more than 15 countries. In collaboration with these IVSNs, a brief information packet was sent to all IVCOs within these networks describing the research and requesting their participation and consent to collaborate in the research project. In total, the researchers established collaborative partnerships with a total of 46 IVCOs. Table 2 describes the distribution of participating IVCOs by country.

Consenting IVCOs selected a sample of VPOs in low- and middle-income countries that would ostensibly be willing to participate in the survey. Because these IVCOs were all members of IVSNs that prioritize development, they represent a particular niche of organizations that are concerned with development effectiveness and are often valued partners in projects with other transnational development organizations. Consequently, the VPOs that partner with these IVCOs also represent a particular segment of organizations that request technical services. This distinction is important because the selected sampling frame generally excludes VPOs involved in facilitating volunteer tourism or other volunteer placements that are not derived from a capacity-based need identified by a VPO. Consequently, results may be biased toward more positive appraisal than surveys that include these alternate types of IVS organizations in their sample (Tiessen 2017). Two criteria were placed on the selection of VPOs, which included: (1) the VPOs should each have a minimum of 1-year working history with the IVCOs, and (2) the VPOs should have hosted a minimum of three international volunteers.

Data Collection

Collaborating IVCOs were given two choices for the administration of surveys to their partners. First, the IVCOs could send the researchers contact details for VPOs within their network. In this case, the researchers followed up with a letter of introduction and a recruitment email to prospective VPOs. The email to VPOs would include a brief introduction to the project, a request for informed voluntary consent to participate, and a direct link to the online survey. If the partner organizations had not responded within 1 week, the researchers sent one follow-up email. As a second alternative, the IVCOs could contact their partners directly with an anonymous link to the online survey. These IVCOs would directly provide a letter of introduction and consent with their recruitment email. No follow-up email would be sent, as there was no method for tracking the rate of response or participation for this method.

All surveys were taken online by the key administrator of the participating VPOs responsible for hosting and managing volunteers. All recruitment material, consent forms, and surveys were translated and provided to VPOs in three languages (English, French, and Spanish). This study was approved by human subject review boards at universities in Canada and the USA, and participation by VPOs was completely voluntary with no financial compensation.

Among organizations contacted directly by the researchers, 1130 VPOs received the survey and 239 responded (22%). The response rate among VPOs contacted recruited by the IVCOs is not known, as not all participating IVCOs could articulate how many VPOs they contacted. However, 81 VPOs responded to the anonymous survey link and the response rate may have been higher for this second method due to the closer relationship between IVCOs and VPOs. From these 320 responses, 32 incomplete responses were dropped from the analysis. In total, the analysis included 288 survey responses from VPOs operating across 68 countries.

Although the sample was quite global overall, responses were skewed toward VPOs that hosted volunteers from South Korea, North America, and Europe. In the final sample, VPOs reported hosting most of their volunteers from South Korea (44%), the USA (35%), and Germany (26%). However, VPOs also reported hosting many volunteers from 47 other countries, including France (15%), the UK (14%), Canada (12%), Japan (12%), Switzerland (11%), and Australia (10%).Footnote 1

Data Analysis

To identify distinctive categories of volunteer models, the researchers initially completed an exploratory principal component analysis (PCA) to determine whether any of the distinguishable categories emerged from statistical analyses. Variables included in the PCA were the duration of volunteer service; perceptions of volunteers’ education, skills, and competencies; group placement status; minimum age of volunteers accepted by VPOs; resources expended by VPOs to host volunteers; and the amount of money VPOs receive to host international volunteers (if any). An unrotated factor solution with a minimum eigenvalue threshold of 1.0 was used to distinguish all principal components. PCA yielded three broad categories (individual long-term volunteers, highly skilled, and older short-term volunteers, and medium-term volunteers). However, several variables failed to load well on any of these three components, with other variables loading on multiple components. Overall, a viable solution could not be attained from PCA alone based on overlapping constructs (e.g., short-term volunteers were alternately perceived as highly skilled or highly unskilled).

As a second method of categorization, the researchers manually coded each case response based on their knowledge of the sending IVCO combined with a manual inspection of survey responses using variables on the duration of service, volunteer age, and the skill level and educational level of volunteers. Although the resulting categories were heuristically determined rather than by a formulaic computation, two researchers independently categorized each case resulting in 93% agreement during the initial coding process. Differences were resolved through more detailed scrutiny, and a discussion between the researchers about each contradictory case.

Manual categorization of case responses resulted in five broad types of volunteers represented in the survey responses: professional short-term, long-term development, less-skilled short-term, less-skilled long-term, and semi-skilled medium-term volunteers. Three of these five types fit well with categories commonly represented in other literature: professional short-term volunteers have significant skills, training, and experience and usually serve for a shorter-time because they are maintaining concurrent employment (Allum 2007; Chang 2005; Sherraden et al. 2008). Long-term development volunteers typically live and work in low-income communities for at least 1 year, and are usually required by the sending IVCO to hold a college degree as a minimum educational requirement (Daniel et al. 2006; Devereux 2008; Sherraden et al. 2006). This model has a long-standing historical precedence tied to Western development theory and practice (Lough 2015b). Less-skilled short-term volunteering is often performed by young people with few marketable skills. It includes some forms of volunteer tourism or “voluntourism” as defined in other studies (Palacios 2010; Wearing and McGehee 2013), though many of the volunteers in this study served for a longer duration than is typical in studies of volunteer tourism. The two remaining categories: less-skilled long-term and semi-skilled medium-term volunteers are not common categories represented in other studies. Although these two forms do not fit tightly with the main forms of IVS discussed and analyzed in prior studies, they were evident in these data and represent the variety and flexibility of volunteering options available to people interested in serving abroad. A depiction of these categories along with basic descriptive statistics of each type is reported in the findings section.

The researchers used multiple methods to test for statistically significant differences. To assess bivariate differences in scale-level measures, the researchers completed correlation analyses and Analysis of Variance (ANOVA), followed by pairwise comparisons using a Tukey post hoc test to determine statistically significant differences. Three binary logistic regressions were then used to assess differences in outcomes across the diverse volunteering models. The survey asked respondents to rate (on a scale from one to five) international volunteers’ effectiveness at performing diverse activities in their organization. To assess the influence of different skill levels of volunteers and to test whether duration of service might influence relationship development and maintenance, three outcomes were chosen for inclusion in this analysis. The three outcomes were recoded into binary dependent variables where 1 = ratings of “excellent” effectiveness, and 0 = ratings of “poor” to “good” effectiveness. For inclusion in the regression, the five-category typology variable was recoded into five dummy variables, and the “professional short-term volunteers” category was used as the reference group in the logistic regressions illustrated in Table 4. For the variable representing groups of volunteers, those who rarely or never host individual volunteers were coded as 1, while those who often or always host individuals were coded as 0.

Findings

The most commonly represented type of volunteering represented in the survey data was long-term development volunteering (n = 104), followed by professional (or highly skilled and experienced) short-term volunteering (n = 58), less-skilled short-term volunteering (n = 51), less-skilled long-term volunteering (n = 37), and moderately skilled medium-term volunteers (n = 36) (See Table 3). A common category not well-represented by the organizations participating in this survey was very short-term volunteer tourism or “voluntourism” as represented in some prior studies. This category is similar to less-skilled short-term volunteering but is a still shorter duration, often in the range of 2–4 weeks or less (Callanan and Thomas 2005; Tourism Research and Marketing 2008). In contrast, the less-skilled “short-term” volunteers in this study served for an average of over 3 months.

Bivariate Correlations

As illustrated in Table 3, findings suggest that, across the different types of volunteers hosted by partner organizations, those with competencies that most fit the needs of the organizations were long-term “development” volunteers (91%) and “professional” short-term volunteers (89%). On the other hand, less-skilled volunteers, regardless of the length of stay, were significantly less likely to have competencies that fit the needs of the host organizations (41–53%). As might be expected, competencies directly correlated with the perceived skill and education level of the volunteers. Professional short-term volunteers were rated as the most skilled (97%) and educated (95%). In comparison with short-term skilled volunteers, long-term development volunteers appeared to have additional noneducation and nonskill-based competencies that fit with organizational needs. Although we initially believed these competencies could relate to motivations, perceived motivations were also lower among less-skilled volunteers.

Both short- and long-term less-skilled volunteers tended to volunteer with organizations with lower minimum age requirements (18.8 and 19.2 years, respectively). In contrast, the oldest volunteers were those who served for a short-term but who had high levels of professional skills and education (21.7 years). In comparison with professional short-term volunteers, all age differences were statistically lower for other types (F = 7.26, df = 4, p < .001) with the exception of moderately skilled medium-term volunteers. Although a 2–3 year age difference may seem somewhat negligible from a practical perspective, findings indicate a somewhat weak but statistically significant linear correlation between VPOs’ measured differences in minimum age requirements and their perceptions of hosting competent volunteers (r = .18, p < .01).

VPO’s perception of hosting volunteers with competencies that fit their organizational needs was not significantly related to the duration of their service (r = .05, p = .40). In fact, the highest proportion of perceived competencies was associated with the volunteer models at the shortest (\(\bar{x}\) = 43 day) and the longest (\(\bar{x}\) = 472 day) durations. When correlating, competency fit with other variables, the volunteers’ skills (r = .69, p < .001) and educational level (r = .54, p < .001) appear to be far more important that the duration of their service. In effect, a longer duration of service may be a detriment to organizational fit among less-skilled volunteers, as less-skilled long-term volunteers received the lowest ratings overall on this measure (although this difference was not significantly different from less-skilled long-term volunteers).

Motivations appear to be highest when volunteers have substantive skills and competencies to contribute. Short-term professional volunteers received the highest motivation ratings (95%), followed by medium-term (89%) and long-term (83%) development volunteers. It would seem that VPOs’ perceptions of skilled volunteers’ motivations tend to decrease as the volunteers’ time with the organization increases. However, the proportional differences in perceived motivation among the more highly skilled categories of volunteers are not statistically significant (p > .05). On the other hand, clear differences emerged from the perceived motivations between skilled and less-skilled volunteers (F = 7.71, df = 4, p < .001), with only 66% of less-skilled volunteers being perceived as highly motivated.

Effectiveness of Volunteer Models

Across all three outcome categories assessed in this study, professional short-term volunteers were ranked higher on perceived effectiveness than many other forms of IVS, which is also why we decided to use this category as a reference group to illustrate some of these statistical differences (see Table 4). No statistically significant differences in effectiveness were evident between short-term and longer-term skilled volunteering models across the three outcomes included in this study. On the other hand, differences between short-term professional volunteering and less-skilled short- and long-term volunteering were statistically significant for two of the three outcomes, and with quite substantial effects.

In comparison with professional short-term volunteers, VPOs hosting less-skilled short- and long-term volunteers were five times less likely to rate volunteers’ ability to help develop capacity in the organization as “excellent” (OR = 5.07 and 4.83, respectively)—supporting our initial hypotheses. Results were somewhat similar when using long-term development volunteers as the reference group (OR = 4.43 and 3.49, respectively). Among both types of more highly skilled volunteering, duration did not appear to matter; in comparison with short-term professional volunteers, VPOs were no more likely to report longer-term development volunteers are more effective at strengthening organizational capacity.

Our assumption that group size would be negatively correlated with capacity-building effectiveness was not supported. Although this correlation was in the correct direction (B = −.33), the group size of volunteers failed to yield a statistically significant difference in VPOs’ perception of volunteers’ perceived effectiveness at building organizational capacity (Wald χ2 = .84, p = .36).

In comparison with less-skilled short-term volunteers, VPOs hosting professional short-term volunteers were 2.5 times more likely to rate volunteers’ effectiveness at developing international relationships as excellent (Wald χ2 = −3.82, β = .39, p < .05). Likewise, in comparison with less-skilled long-term volunteers, VPOs hosting professional short-term volunteers were 3.5 times more likely to rate these volunteers’ as highly effective at developing international relationships (Wald χ2 = −6.05, β = .29, p < .05). In partial confirmation of our hypothesis, long-term development volunteers were viewed as 2.6 times more effective at developing international relationships than less-skilled short-term volunteers (Wald χ2 = −4.50, β = .38, p < .05).Footnote 2 However, longer-term volunteers were not viewed as more or less effective at relationship building than short-term professional volunteers. Likewise, less-skilled long-term volunteers showed no significant differences in relationship building than shorter-term forms of volunteering.

As hypothesized, hosting a group of volunteers rather than an individual volunteer does appear to matter for developing international relationships. VROs that rarely host individual volunteers were nearly twice as likely as VROs that often or always host individual volunteers to report these volunteers as excellent at developing international relationships (Wald χ2 = 5.26, β = 1.93, p < .05). As predicted, neither group size nor the type or volunteer service was correlated with volunteers’ perceived effectiveness at performing manual labor.

Discussion and Conclusions

Limitations

It is important to first recognize how sampling bias may affect findings and overall research generalizations. Because all of the IVCOs included in this study are part of IVSNs that prioritize social and economic development, their associated VPOs represent a partnership approach that considers the requests by the VPOs for technical assistance. Our selection of these organizations is contrasted with un-networked IVCOs that may operate as placement agencies driven by various profit-seeking and/or proselytizing motives—some of which may host volunteers that do not have competencies that align with the needs of VPOs. In this study, 53% of even the least-skilled forms of short-term volunteering reportedly had competencies that fit the needs of the partner organizations. These findings are therefore limited in generalization to other more highly criticized forms of IVS such as heavily profit-driven, religious- or volunteer supply-oriented models that may have weaker partnership arrangements (Baillie Smith et al. 2013; Lyons et al. 2012; Perold et al. 2013; Raymond and Hall 2008).

Likewise, this study investigated volunteers’ effectiveness at meeting various development outcomes, with minimal assessment of structural inequalities or barriers to effective participation—such as reciprocity or equality of opportunity. This is important because perceptions of development outcomes are loaded with perceptions of international donor requirements and accountability mechanisms that were not assessed in this study. If the effectiveness of international volunteers is examined in the context of meeting donor deliverables, and international volunteers are seen as integral to that process, this raises an inherent bias that should be considered when interpreting these findings. Likewise, if effectiveness was perceived as responding to community needs and national interests, which may include increasing opportunities for youth in those countries to find employment or get on-the-job training similar to the type of experiences that international volunteers have, it may have resulted in a different considerations of effectiveness.

Another challenge is the wide variation of volunteers that VPOs often receive. VPOs that host many volunteers likely have difficulty remembering and distinguishing between the many volunteers that they have worked with over the years. Survey “halo effect” tends to result in respondents’ recall of the most likeable or effective volunteers, while having fun memories of the odd or unusual volunteers who come through their programs (Feeley 2002). As organizations reflect on the sometimes hundreds of international volunteers they have worked with in the past, it is likely difficult to measure, evaluate, and summarize their experiences. Because this survey is based on self-report and a general recall of knowledge, it is difficult to make firm conclusions without systematic performance measurement evaluations from partner organizations and a careful review of this information.

Among programs that host volunteers for longer than 1 year, we can assume clear variation between those that only report 91% of their volunteers as less skilled, compared to those that report 91% of their volunteers as highly skilled. However, with a higher number and variety of responses, future research could possibly further subdivide these groups by additional program components, such as the number of volunteers serving together, reciprocal directionality (e.g., North–South, South–South.), and cultural immersion practices (Sherraden et al. 2006, 2008). Indeed, the different mandates of diverse organizations certainly play a role in the type of volunteer selected and the skill sets demanded of these volunteers, and greater variance could be captured with a more diverse sampling frame.

It is also important to note that even within a single category identified in this study, there may be significant variation. For instance, short-term skilled volunteering could include 3-week trips for experts in agriculture (e.g., the USAID-supported Farmer-to-Farmer program) to mid-career medical professionals that repeatedly volunteer for a 1-week duration over the course of 5 years (e.g., Singapore International Volunteers). The same category could also include short-term “experteering” facilitated by the Moving Worlds Institute or volunteering with the US Peace Corps Response program, which send experienced professionals or licensed physicians or nurses for a minimum of 3 months. Keeping these limitations in mind, the study findings are largely consistent with expectations based on previous studies and mostly confirm our initial hypotheses.

Skilled and Unskilled Volunteering

The first hypothesis aimed to test whether skilled volunteering will be more effective than unskilled volunteering at strengthening organizational capacity. This hypothesis was strongly supported in this study; both short- and long-term skilled volunteers were viewed as substantially more effective than less-skilled forms of volunteering at building organizational capacity. This is also generally consistent with the previously reviewed studies. This difference might also help to explain why perceived motivations to effectively perform their volunteer work were lower among less-skilled volunteers than high-skilled volunteers. Motivations appear to be highest when volunteers have substantive skills and competencies to contribute.

The perceived skill and education levels of volunteers also appear to be positively associated with a better fit between the volunteers’ competencies and the needs of the partner organizations. However, despite very low ratings of skill and education, nearly half of VPOs that hosted less-skilled volunteers reported that most of their volunteers had competencies that fit their organizations’ needs. Recognizing that these competencies are not associated with higher education or technical skills, they may reflect more basic but still useful competencies that fit the needs of VPOs. Although these competencies were not measured in this study, they may represent areas such as proficiency in English, acquiring resources through the volunteers’ social networks, or volunteers’ more general knowledge of health or education.

Although age differences were not explicitly tested in this study, it is important to recognize that a 2- to 3-year difference in minimal age requirements at a programmatic level seems to make a real difference in terms of overall skills, competencies, and motivations that volunteers bring to the organization (see Table 3). This difference is likely somewhat shaped by the important influence of higher education during critical years that young people gain and practice professional skills (i.e., between 18 and 22 years old). Volunteers finishing their degrees in higher education are likely considering the relationship between their volunteer work and the career plans. They may see the volunteer opportunity as a time to develop and implement their skills.

Duration of Service

The second hypothesis aimed to test whether both forms of longer-term volunteering will be more effective that short-term volunteering at building relationships with local respondents. This hypothesis was only partially confirmed. While long-term development volunteers were viewed as more effective at developing international relationships than less-skilled short-term volunteers, they were not viewed as significantly more or less effective at relationship building than short-term professional volunteers. Likewise, less-skilled long-term volunteers showed no significant differences in relationship building compared to shorter-term forms of volunteering.

Considering previous studies, which consistently make a case for longer-term volunteering in relationship building (Heron 2011; Tiessen 2017), how might we explain this difference? For one, these findings suggest that duration of service is more complex than a binary delineation between shorter and longer-term placements. Indeed, long-term development volunteers were viewed as substantially more effective at developing international relationships than less-skilled short-term volunteers. This suggests that more days does equate with better relational outcomes when volunteers’ skills are lacking. Both short- and long-term volunteers can be quite effective at building relationships, developing capacity, etc., when they have skills and competencies that fit the needs of VPOs. As another potential explanation, returned volunteers frequently report ongoing communication with partners as a result of email communication and other social media, which might help explain the development of relationships, even when service is only a short duration (Lough et al. 2009).

Duration of service was also not significantly associated with differences in volunteers’ perceived motivations to perform effectively. As VPOs’ relationships with volunteers deepened over time, it is likely that they were able to better recognize more reflexive and overlapping motivations that drove volunteers to engage—such as the desire to travel and have an adventure, to make new friends, or to acquire additional skills for future employment, combined with, in many instances, the desire to contribute to development outcomes. This assumption could be tested in future research. The priority attached to motivations of an egoistic nature versus those of a more solidaristic commitment may become clearer as VPOs have more opportunities to observe the contributions and commitments of the volunteers.

With one exception, VPO’s perceptions of hosting volunteers with competencies that fit their organizational needs were also not significantly related to the duration of their service. Likewise, no statistically significant differences in perceived capacity building were evident between professional short-term volunteering and skilled longer-term development volunteering. Although neither of these findings were included in our initial hypotheses, they are worth flagging. When international volunteers are skilled, they may be able to effectively meet the diverse needs of VPOs regardless of the duration of their service.

Skills and Duration for Manual Labor

The third hypothesis proposed that all types of international volunteers will be equally effective at performing manual labor. This hypothesis was fully supported; VPOs did not indicate a significant preference for any single type of volunteering as more effective at performing manual labor. This may be partially due to the diverse nature and wide interpretation of “manual labor” or because specialized skills and long-duration of service may not be needed to accomplish projects relying on manual labor. Prior research does suggest that some VPOs may prefer local volunteers for manual labor tasks (Lough 2012), though research in more diverse contexts is needed to confirm and understand this preference.

Individual and Group-based Volunteering

Although we did not explicitly set out to test the directional influence of group-based volunteering on outcomes, this study does provide initial results that may warrant further reflection and research. However, understanding the influence of a group dynamic is somewhat problematic in this study. As implied earlier, the survey asks VPOs to rate whether volunteers are effective at building international relationships but does not specify who volunteers are building these relationships with. Because volunteer workcamps are often comprised of multinational participants, they may be good at creating international relationships with each other but may interact less-meaningfully with host organizations. Similarly, individual volunteers may be good at building new relationships with hosting communities and organizations but may have fewer interactions with other volunteers. Because of this, we are reluctant to draw conclusions between group size and its apparent association with international relationship building.

Summary

Although this study aimed to assess how the duration of service and educational/skill requirements affect several outcomes, we recognize that IVCOs and VPOs will have greater success and impact when those deliverables are explicitly programmed into the volunteer activities and model (Powell and Bratović 2006). Well-facilitated programs with comprehensive volunteer preparation, a careful eye on structural inequalities, and sound post-placement support can likely meet a diverse set of programmatic priorities, whether focused on strengthening capacity in partner organizations, developing international relationships, or performing manual labor. Nonetheless, when various forms of IVS are conceptualized within the same uniform framework, people can easily make incorrect conclusions about the benefits or challenges of IVS. This study contributes to knowledge development by breaking this framework apart to analyze the influence of diverse program characteristics.

This study also contributes by empirically demonstrating that some forms of volunteering may be better suited at meeting particular outcomes. Although this study sample is not globally representative or all-inclusive, it demonstrates how the complexity in program options can result in disparate perceptions of volunteer effectiveness. In order to generate useful policy and program implications, future research on IVS needs to be more precise about the particular forms of volunteering under study, and to consider how diverse models intersect with program frameworks for comparative analysis. Additional research could further document how other variables affect outcomes, such as VPOs’ experiences collaborating with international volunteers, including critical issues such as power dynamics, decision-making authority, and the ability to vet volunteers. Such research could uncover relationships between program options and additional outcomes not accounted for in this research. As future research on IVS considers more diverse individual and institutional characteristics, knowledge of effective practices associated with particular outcomes can use this evidence to drive critical program decisions.

Change history

11 April 2018

The PDF version of this article was reformatted to a larger trim size.

Notes

Because VPOs could select more than one country in the survey, combined totals will not equal 100%.

Because Table 4 uses less-skilled short-term volunteers as the reference group, this finding is not directly illustrated in the table.

References

Adelman, C., Schwartz, B., & Riskin, E. (2016). 2016 index of global philanthropy and remittances. Washington D.C.: The Center for Global Prosperity (CGP) at the Hudson Institute. http://gpr.hudson.org/files/publications/IndexGlobalPhilanthropy2007.pdf.

Alloni, R., D’Elia, A., Navajas, F., & De Gara, L. (2014). Role of clinical tutors in volunteering work camps. The Clinical Teacher, 11(2), 116–119. https://doi.org/10.1111/tct.12072.

Allum, C. (2007). International volunteering and co-operation: New developments in programme models. IVCO 2007 Conference Report. Montreal, Canada: International FORUM on Development Service.

Baillie Smith, M., Laurie, N., Hopkins, P., & Olson, E. (2013). International volunteering, faith and subjectivity: Negotiating cosmopolitanism, citizenship and development. Geoforum, 45, 126–135.

Bentrim, E. M., & Henning, G. W. (2016). Tenet one: Building capacity in student affairs assessment: Roles of student affairs assessment coordinators. In E. Bentrim, G. W. Henning, & K. Yousey-Elsene (Eds.), Coordinating student affairs divisional assessment: A practical guide (pp. 43–64). Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishing.

Brayley, N., Obst, P., White, K. M., Lewis, I. M., Warburton, J., & Spencer, N. M. (2014). Exploring the validity and predictive power of an extended volunteer functions inventory within the context of episodic skilled volunteering by retirees. Journal of Community Psychology, 42(1), 1–18.

Broad, S. (2003). Living the Thai life—a case study of volunteer tourism at the Gibbon Rehabilitation Project, Thailand. Tourism Recreation Research, 28(3), 63–72.

Callanan, M., & Thomas, S. (2005). Volunteer tourism. In M. Novelli (Ed.), Niche tourism (pp. 183–200). Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann Oxford.

CCIVS. (1984). New trends in voluntary service. Paris: Coordinating Committee for International Voluntary Service.

Chang, W.-W. (2005). Expatriate training in international nongovernmental organizations: A model for research. Human Resource Development Review, 4(4), 440–461.

Coghlan, A. (2007). Towards an integrated image-based typology of volunteer tourism organisations. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 15(3), 267–287.

Corps, Peace. (2016). Peace Corps fiscal year 2017: Congressional budget justification. Washington, D.C.: Peace Corps.

Cronin, K., & Perold, H. (2008). Volunteering and social activism: Pathways for participation in human development. Washington DC, and Bonn Germany: International Association for Volunteer Effort (IAVE), United Nations Volunteers (UNV) Program, and World Alliance for Citizen Participation (CIVICUS).

CVO. (2007). The impact of international volunteering on host organizations: A summary of research conducted in India and Tanzania. Ireland: Comhlámh’s Volunteering Options.

Daniel, P., French, S., & King, E. (2006). A participatory methodology for assessing the impact of volunteering for development: Handbook for volunteers and programme officers. Bonn: United Nations Volunteers & Centre for International Development Training.

Davis Smith, J. (2000). Volunteering and social development. Voluntary Action, 3(1). Available online at the Institute for Volunteering Research website.

Davis Smith, J., Ellis, A., Brewis, G., Smith, J., Ellis, A., Brewis, G., et al. (2005). Cross-national volunteering: A developing movement? In J. Brundey (Ed.), Emerging areas of volunteering (pp. 63–76). Indianapolis: ARNOVA.

Devereux, P. (2008). International volunteering for development and sustainability: Outdated paternalism or a radical response to globalisation. Development in Practice, 18(3), 357–370.

Devereux, P. (2010). International volunteers: Cheap help or transformational solidarity toward sustainable development. Perth: Murdoch University.

Devereux, P., & Mukwashi, A. (2014). Integrating volunteering in the next decade: A 10 year plan of action 2016–2025. In IVCO 2014: Volunteering in a Convergent World: Fostering Cross-Sector Collaborations Towards Sustainable Development Solutions. Lima, Peru, Peru: International Forum for Volunteering in Development.

Diprose, K. (2012). Critical distance: Doing development education through international volunteering. Area, 44(2), 186–192. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4762.2011.01076.x.

Dwyer, M. (2004). More is better: The impact of study abroad duration. Frontiers, The Interdisciplinary Journal of Study Abroad, 10, 151–163.

Feeley, T. H. (2002). Evidence of halo effects in student evaluations of communication instruction. Communication Education, 51(3), 225–236.

Forum. (2015). The Tokyo Call to Action. Tokyo: International Forum for Volunteering. in Development.

Furco, A. (1996). Service-learning: A balanced approach to experiential education. In B. Taylor (Ed.), Expanding boundaries: Service and learning (pp. 2–6). Washington, DC: Corporation for National Service.

Georgeou, N. (2012). Neoliberalism, development, and aid volunteering. Routledge studies in development and society. New York: Routledge.

Gillette, A. (1968). One million volunteers: The story of volunteer youth service. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

Gillette, A. (1972). Aims and organization of voluntary service by youth. Community Development Journal, 7(2), 99–129.

Graham, L. A., Mavungu, E. M., Perold, H., Cronin, K., Muchemwa, L., & Lough, B. J. (2012). International volunteers and the development of host organisations in Africa: Lessons from Tanzania and Mozambique. In SAGE Net (Ed.), International volunteering in Southern Africa: Potential for change? (pp. 31–59). Bonn: Scientia Bonnensis.

Guttentag, D. A. (2009). The possible negative impacts of volunteer tourism. International Journal of Tourism Research, 11(6), 537–551.

Heron, B. (2007). Desire for development: Whiteness, gender, and the helping imperative. Waterloo: Wilfrid Laurier University Press.

Heron, B. (2011). Challenging indifference to extreme poverty: Considering Southern perspectives on global citizenship and change. Ethics and Economics, 8(1), 110–119.

Hills, G., & Mahmud, A. (2007). Volunteering for impact: Best practices in international corporate volunteering. FSG Social Impact Advisors, Pfizer Inc., & the Brookings Institution.

Howard, J., & Burns, D. (2015). Volunteering for development within the new ecosystem of international development. IDS Bulletin, 46(5), 5–16. https://doi.org/10.1111/1759-5436.12171.

Illich, I. (1968). To Hell with good intentions. New York, NY: The Commission on Voluntary Service and Action.

Jones, A. (2005). Assessing international youth service programmes in two low income countries. Voluntary Action: The Journal of the Institute for Volunteering Research, 7(2), 87–100.

Lough, B. J. (2012). Participatory research on the contributions of international volunteerism in Kenya: Provisional results. Fitzroy, Australia: International FORUM on Development Service. http://www.unite-ch.org/12archiv/archiv09_study/ParticipatoryResearch-Contributions-International-Volunteerism-Kenya.pdf.

Lough, B. J. (2015a). A decade of international volunteering from the United States, 2004 to 2014 (CSD Resear.). St. Louis, MO: Washington University, Center for Social Development.

Lough, B. J. (2015b). The evolution of international volunteering. Bonn: United Nations Volunteers.

Lough, B. J. (2016a). Global partners for sustainable development: The added value of Singapore international foundation volunteers. Singapore: Singapore International Foundation.

Lough, B. J. (2016b). Reciprocity in international volunteering. Oslo: FK Norway.

Lough, B. J., McBride, A. M., & Sherraden, M. S. (2009). Perceived effects of international volunteering: Reports from alumni. St Louis, MO: Center for Social Development, Washington University.

Lough, B. J., & Xiang, X. (2016). Skills-based international volunteering among older adults from the US. Administration & Society, 48(9), 1085–1100. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095399714528179.

Lyons, K. D., Hanley, J., Wearing, S., & Neil, J. (2012). Gap year volunteer tourism: Myths of global citizenship? Annals of Tourism Research, 39(1), 361–378. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2011.04.016.

Lyons, K. D., & Wearing, S. (2012). Reflections on the ambiguous intersections between volunteering and tourism. Leisure Sciences, 34(1), 88–93.

McBride, A. M., Benítez, C., & Danso, K. (2003). Civic service worldwide: Social development goals and partnerships. Social Development Issues, 25(1/2), 175–188. Available on GSI website.

McBride, A. M., & Daftary, D. (2005). International service: History and forms, pitfalls and potential. St. Louis, MO: Center for Social Development, Washington University.

McGehee, N. G., & Santos, C. A. (2005). Social change, discourse and volunteer tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 32(3), 760–779.

Moresky, R. T., Eliades, M. J., Bhimani, M. A., Bunney, E. B., & VanRooyen, M. J. (2001). Preparing international relief workers for health care in the field: an evaluation of organizational practices. Prehospital and Disaster Medicine, 16(4), 257–262.

Ogden, A. (2008). The view from the veranda: Understanding today’s colonial student. Frontiers: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Study Abroad, 15, 35–55.

Palacios, C. M. (2010). Volunteer tourism, development and education in a postcolonial world: Conceiving global connections beyond aid. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 18(7), 861–878. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669581003782739.

Percival, J. (2009). More retired people opting to work abroad as volunteers. New York: The Guardian.

Perold, H., Graham, L. A., Mavungu, E. M., Cronin, K., Muchemwa, L., & Lough, B. J. (2013). The colonial legacy of international voluntary service. Community Development Journal, 48(2), 179–196. https://doi.org/10.1093/cdj/bss037.

Perold, H., Mavungu, E. M., Cronin, K., Graham, L. A., Muchemwa, L., & Lough, B. J. (2011). International voluntary service in Southern African Development Community (SADC): Host organisation perspectives from Mozambique and Tanzania. Volunteer and Service Enquiry Southern Africa (VOSESA): Johannesburg.

Pinkau, I. (1977). An evaluation of development services and their cooperative relationships (Vol. I). Washington DC: Society for International Development.

Pless, N. M., & Borecká, M. (2014). Comparative analysis of International Service Learning Programs. Journal of Management Development, 33(6), 526–550. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMD-04-2014-0034.

Plewes, B., & Stuart, R. (2007). Opportunities and challenges for international volunteer co-operation. IVCO Conference Report. Fitzroy, Australia: International FORUM for Development Service.

Powell, S., & Bratović, E. (2006). The impact of long-term youth voluntary service in Europe: A review of published and unpublished research studies. Brussels: AVSO and ProMENTE.

Power, S. (2007). Gaps in development: An analysis of the UK international volunteering sector. London: Tourism Concern.

Raymond, E. M., & Hall, C. M. (2008). The development of cross-cultural (mis)understanding through volunteer tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 16(5), 530–543. https://doi.org/10.2167/jost796.0.

Rehberg, W. (2005). Altruistic individualists: Motivations for international volunteering among young adults in Switzerland. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 16(2), 109–122.

Sherraden, M. S., Lough, B. J., & McBride, A. M. (2008). Effects of international volunteering and service: Individual and institutional predictors. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 19(4), 395–421.

Sherraden, M. S., Stringham, J., Costanzo, S., & McBride, A. M. (2006). The forms and structure of international voluntary service. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 17, 163–180.

Simpson, K. (2004). “Doing development”: The gap year, volunteer-tourists and a popular practice of development. Journal of International Development, 16, 681–692.

Sin, H. L. (2009). Volunteer tourism—“involve me and I will learn”? Annals of Tourism Research, 36(3), 480–501.

Singh, T. V. (2002). Altruistic tourism: Another shade of sustainable tourism. The case of Kanda community. Tourism (Zagreb), 50(4), 361–370.

Stephens, C., Breheny, M., & Mansvelt, J. (2015). Volunteering as reciprocity: Beneficial and harmful effects of social policies to encourage contribution in older age. Journal of Aging Studies, 33, 22–27.

Sykes, K. J. (2014). Short-term medical service trips: A systematic review of the evidence. American Journal of Public Health, 104(7), e38–e48.

Thomas, G. (2001). Human traffic: Skills, employers and international volunteering. London: Demos.

Tiessen, R. (2017). Learning and volunteering abroad for development: Host organisation and volunteer perspectives. Abingdon: Routledge Press.

Tiessen, R., & Heron, B. (2012). Volunteering in the developing world: The perceived impacts of Canandian youth. Development in Practice, 22(1), 44–56.

Tiessen, R., & Huish, R. (Eds.). (2014). Globetrotting or global citizenship?: Perils and potential of international experiential learning. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, Scholarly Publishing Division.

Tomazos, K., & Cooper, W. (2012). Volunteer tourism: At the crossroads of commercialisation and service? Current Issues in Tourism, 15(5), 405–423.

Tourism Research and Marketing. (2008). Volunteer tourism: A global analysis. Barcelona, Spain: Tourism Research and Marketing & the Association for Tourism and Leisure Education.

Volpini, F. (2016). Report summary: Impacts of international volunteer workcamps. Paris, France: Solidarites Jeunesses, Coordinating Committee for International Voluntary Service, Better World, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Watts, M. (2002). Should they be committed? Motivating volunteers in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. Development in Practice, 12(1), 59–70.

Wearing, S., & McGehee, N. G. (2013). Volunteer tourism: A review. Tourism Management. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2013.03.002.

Woods, D. E. (1971). Volunteers in community development. Paris: Coordinating Committee for International Voluntary Service, UNESCO.

Woods, D. E. (1980). International research on volunteers abroad. Volunteers, voluntary associations, and development, 21(3–4), 47–57.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported with funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (Grant Number: 890-2014-0051).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Lough, B.J., Tiessen, R. How do International Volunteering Characteristics Influence Outcomes? Perspectives from Partner Organizations. Voluntas 29, 104–118 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-017-9902-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-017-9902-9