Abstract

The proliferation of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) since the 1970s has generated a wealth of research as to the causes and implications of the rise of this sector. Public awareness of NGOs and their activities has grown as well, at least in part due to increased media coverage of the organizations and the situations to which they respond. Although NGOs are not new to global polity, media attention to them as a sector only really began to take off in the 1990s. Using quantitative and qualitative analysis of two international newspapers from 1985-2010, this study explores the legitimation process of NGOs and examines the role of categorization and labeling in this process. The results show that the establishment of a distinct label in the media served to propel cognitive recognition of NGOs, and that media coverage reflects changes in cognitive legitimacy over time.

Résumé

La prolifération des organismes non gouvernementaux (ONG) depuis les années soixante-dix a généré une riche gamme de recherches sur les causes et les effets de cette montée dans le secteur. La sensibilisation du public aux ONG et à leurs activités est aussi à la hausse, au moins et en partie à cause de la couverture que font les médias de ces organismes et des situations auxquelles elles réagissent. Même si les ONG ne sont pas des nouveautés pour la politie mondiale, l’attention qu’elle génère dans les médias en tant que secteur ne remonte toutefois qu’aux années quatre-vingt-dix. À l’aide d’analyses quantitative et qualitative du contenu de deux journaux internationaux datant de 1985 à 2010, cette étude explore le processus de légitimation des ONG et étudie le rôle qu’ont joué la catégorisation et l’étiquetage dans ce dernier. Les résultats démontrent que la mise en place d’une catégorie distincte dans les médias a propulsé la reconnaissance cognitive des ONG et que la couverture médiatique accélère la formation identitaire organisationnelle et la légitimité d’un secteur.

Zusammenfassung

Die starke Ausbreitung nicht-staatlicher Organisationen seit den siebziger Jahren hat zu einer Fülle von Forschungsstudien zu den Ursachen und Folgen des Wachstums dieses Sektors geführt. Das öffentliche Bewusstsein über nicht-staatliche Organisationen und ihre Aktivitäten ist ebenfalls angestiegen, was zumindest teilweise auf die vermehrte Medienberichterstattung über die Organisationen und die Situationen, auf die sie reagieren, zurückgeführt werden kann. Zwar sind nicht-staatliche Organisationen im globalen politischen System nichts Neues, doch als Sektor wurde ihnen erst in den neunziger Jahren vermehrte Aufmerksamkeit von den Medien geschenkt. Anhand einer quantitativen und qualitativen Analyse zweier internationaler Zeitungen über den Zeitraum von 1985 bis 2010 erforscht diese Studie den Legitimationsprozess nicht-staatlicher Organisationen und untersucht die Rolle der Kategorisierung und Kennzeichnung in diesem Prozess. Die Ergebnisse zeigen, dass die Etablierung einer separaten Kategorie in den Medien die kognitive Anerkennung nicht-staatlicher Organisationen vorantrieb und die Medienberichterstattung die organisatorische Identitätsbildung und die Legitimität eines Sektors erhöht.

Résumén

La proliferación de organizaciones no gubernamentales (ONG) desde los años 1970 ha generado una abundancia de investigaciones en cuanto a las causas e implicaciones del auge de este sector. La concienciación pública sobre las ONG y sus actividades ha aumentado también, al menos en parte debido a la creciente cobertura dada por los medios de comunicación a las organizaciones y a las situaciones a las que responden. Aunque las ONG no son nuevas para el sistema político mundial, la atención de los medios de comunicación sobre ellas como sector sólo comenzó a despegar realmente en los años 1990. Utilizando un análisis cuantitativo y cualitativo de dos periódicos internacionales de 1985-2010, el presente estudio explora el proceso de legitimación de las ONG y examina el papel de la categorización y etiquetado en este proceso. Los resultados muestran que el establecimiento de una categoría clara en los medios de comunicación sirvió para impulsar el reconocimiento cognitivo de las ONG, y que la cobertura de los medios aumenta la formación de identidad organizativa y la legitimidad de un sector.

摘要

非政府组织(NGO)自20世纪 70 年代以来的发展,引发了关于这一领域兴盛的原因和影响的大量研究。NGO 的公众意识及其活动也随之发展,至少部分是由于组织更强的宣传报道和它们对于事态的响应而造成。尽管对于全球政治而言 NGO 并非新鲜事物,但媒体到20世纪90年代才开始将其作为一个专门领域来加以关注。本研究使用1985年 - 2010 年的两份国际报纸进行定量和定性分析,探索 NGO 的合法化过程,并研究分类和标记在该过程中的作用。结果显示,在媒体中确立独特的分类有助于推动 NGO 的认知识别,而宣传报道则增强了组织认同的形成过程以及领域的合法性。

ملخص

إنتشار المنظمات الغير حكومية (NGOs) منذ 1970 نتج عنه ثروة من الأبحاث كأسباب وآثار لنمو هذا القطاع. قد نما الوعي العام للمنظمات الغير حكومية (NGOs) وأنشطتهم كذلك، على الأقل جزئيا" بسبب زيادة التغطية الإعلامية للمنظمات والحالات التي تستجيب لها. على الرغم من أن المنظمات الغير حكومية (NGOs) ليست جديدة على نظام الحكم العالمي، إنتباه وسائل الإعلام لهم كقطاع فقط حقا" بدأت تنطلق في 1990. إستخدام التحليل الكمي والنوعي لصحيفتين عالميتين من 1985- 2010، تكتشف هذه الدراسة عملية إضفاء الشرعية على المنظمات الغير حكومية (NGOs) وتدرس دور التصنيف ووضع العلامات في هذه العملية. أظهرت النتائج أن إنشاء فئة مميزة في وسائل الإعلام ساهمت في دفع الإعتراف المعرفي للمنظمات الغير حكومية(NGO)، وأن التغطية الإعلامية تزيد من تشكيل الهوية التنظيمية والشرعية للقطاع. ح.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The 1970s and 1980s were witness to an explosive growth in the number of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) (Union of International Associations [UIA] 2011–2012), yet not until the 1990s did the organizations become publicly recognized as a sector rather than as individual activist organizations. Although the strength of NGOs may lie in their individual identity and the causes for which they advocate, their power is due at least in part to a shared identity that took root in the 1990s and served to stimulate recognition—and legitimacy—and propel the sector into becoming a major player in the global arena.

According to Carroll and Hannan (1989), tracing the growth in number of organizations—organizational density—over time should tell us something about their cognitive legitimacy. Hannan (1997) points out that the original density dependence theory suggests a relationship between cognitive legitimacy and density as one of strict reversibility, meaning that changes to density result in commensurate changes in legitimacy. However, the revised density dependence theory notes that a decline in density does not automatically result in a decline in legitimacy, just as a rise in organizations does not necessarily result in a rise in legitimacy beyond a certain point in organizational evolution. In an industry that already enjoys cognitive legitimacy, this status is not necessarily threatened if there are fewer organizations within that industry at any given time. The original postulation with regard to obtaining cognitive legitimacy, however, remains the same: density legitimates. However, McKendrick et al. (2003) indicate that density alone does not ensure legitimacy. They argue that acquiring cognitive legitimacy also requires a collective identity recognizable by the public.

Scholars have increasingly come to see the media as playing a pivotal role in the legitimation process of a sector (Andrews and Caren 2010; Deephouse and Suchman 2008; Glynn and Navis 2013; Kennedy 2008). The media increases public awareness and co-create a category and cognitive recognition (McKendrick et al. 2003; Navis and Glynn 2010). When a group of organizations follows specific rules, doing so necessarily categorizes those organizations (Glynn and Abzug 2002). This initial categorization creates a collective identity that can foster legitimacy and attract resources. By being able to name the category specifically, audiences place organizations into a particular form (Hsu and Hannan 2005); an organization’s identity is comprised in part of belonging to this form (Ganesh 2003; Hsu and Hannan 2005; Pólos et al. 2002).

The existence alone of a group of organizations operating within the same domain is thus not sufficient to achieve legitimacy. Audience designation of these actors into a particular group with a collective label is fundamental in the legitimacy process (Fiol and Romanelli 2012) because labels allow for increased recognition by audiences, thus enhancing overall cognition (Hsu and Hannan 2005). In the case of NGOs, Salamon and Anheier indicated in 1992 that without a common understanding of what the sector is and an effective term with which to define it, development of the field might be impeded.

Given the emphasis by leading scholars in the field on the importance of NGOs to the global order (Boli and Thomas 1997; Salamon 1994; Teegen et al. 2004; Yaziji and Doh 2009), studying NGO legitimacy appears to be a relevant undertaking. Although Salamon (1994) stresses that the public was already conscious of organizations such as Amnesty International, Red Cross, and Greenpeace, the public did not identify these organizations as a group at that time. These groups had common features—for example, nonprofit, nongovernmental, international—and included private organizations, international pressure groups, and voluntary agencies (Martens 2002), but the term “nongovernmental organization” was not widely used in the media. This began to change in the mid-1990s; this study centers around that change and what we might learn about NGO legitimacy from it.

Specifically, this research investigates when NGOs obtained taken-for-grantedness. We do so by tracing the emergence, rise, and framing of “nongovernmental organization” in print media. We maintain that mapping the use of the term “nongovernmental organization” and the way NGOs are framed in two leading international newspapers will reveal changes in the organizations’ cognitive legitimacy. This approach allows us to “recognize when changes in population characteristics and boundaries reflect deep changes in the social and cultural standing of the population” (Hsu and Hannan 2005, p. 482). We thus expect that tracing the development of NGOs as viewed through the lens of the media will not only provide information about NGOs but also about social developments in general.

This paper contributes to the literature on nongovernmental organizations by showing when the public became aware of the organizations as a sector (Salamon 1994), the importance of “nongovernmental organization” as an identifying label (Glynn and Navis 2013; McKendrick et al. 2003), and changes in the way NGOs have been discussed in newspapers over time (De Souza 2010). The study resulted in a number of findings about nongovernmental organizations that to best of our knowledge have not been previously reported. Regarding organizational legitimacy, our research points to changes in the legitimacy perceptions of nongovernmental organizations, and illustrates how newspaper coverage reflects shifts in understanding (Kennedy 2008; Pollock and Rindova 2003) of NGOs.

Organizational Legitimacy

Societal values dictate organizational behavior to the extent that not to operate in line with these values would threaten the survival of the organization (Parsons 1956; Meyer and Rowan 1977; Dowling and Pfeffer 1975). This principle is the foundation of organizational legitimacy. A legitimate organization is one that has been determined by society or a particular audience within society to be operating according to existing social values, norms, and expectations (Ashforth and Gibbs 1990; Deephouse and Carter 2005; Suchman 1995).

Suchman (1995) identifies three types of organizational legitimacy: pragmatic, moral, and cognitive. Pragmatic legitimacy involves an organization providing a good or service to a constituency and in return receiving support from that constituency. Pragmatic legitimacy is often reflected in policies and performance standards. Moral legitimacy is granted by audiences when the organization is judged to be ethically correct based on societal values by a segment of society or society-at-large (Bitektine 2011). It involves an evaluation of an organization’s products, procedures, and structures as “the right thing to do” (Suchman 1995, p. 579). Put simply, pragmatic legitimacy reflects an organization’s “responsiveness,” whereas moral legitimacy reflects an organization’s propriety (Suchman 1995, p. 578).

In contrast to pragmatic and moral legitimacy, Suchman (1995) states that an organization obtains cognitive legitimacy when it helps society make sense of and bring order to its environment, or when the organization has become so institutionalized that we could not imagine things being any other way. In their discussion of taken-for-grantedness, Aldrich and Fiol (1994) indicate that cognitive legitimation is the result of awareness of, or familiarity with, a product or field. When an organization reaches taken-for-grantedness, it becomes less susceptible to scrutiny of its right to exist (Bitektine 2011; Meyer and Rowan 1977; Suchman 1995). It is not surprising, then, that cognitive legitimacy is the most difficult form of legitimacy to obtain (Suchman 1995). However, Deephouse and Suchman (2008) heed researchers to remember that obtaining one type of legitimacy may result in increasing one or both of the other types as well.

Media, Framing, and Legitimacy

Media attention is defined here as “the amount of prominence or coverage that an actor, event, or issue receives” (Andrews and Caren 2010, p. 843). It can be important to obtaining legitimacy and access to resources (Kennedy 2008). Media coverage can also be used to study and operationalize legitimacy (Baum and Powell 1995). In their research of the automobile industry, Hannan et al. (1995) found that the cognitive legitimacy of the industry increased as the news stories about automobiles increased. The more the information about the new organizational form spreads through the news and then to the public, the closer the form comes to taken-for-granted status (Hannan et al. 1995). Dowling and Pfeffer (1975) maintain that the values and norms of a society determine what is considered legitimate, and these values and norms are expressed in written and other communication channels. Pollock and Rindova (2003, p. 632) refer to the media as a “propagator” of legitimacy; Deephouse and Suchman (2008) state that the media is an indicator of legitimacy. They argue that because it can influence and reflect societal opinion, it has an important part to play in legitimacy research.

One of the ways that legitimacy can be studied in the media is through frame analysis. Frames in media discourse such as newspaper articles both reflect and shape public opinion. They are indicative of social values, but can also serve to shift those values and create meaning for the audience (Entman 1993; Gamson and Modigliani 1989). A media frame can be defined as “a central organizing idea” which is utilized to “make sense of relevant events, suggesting what is at issue” (Gamson and Modigliani 1989, p. 3). Matthes (2012, p. 249) describes frames as “selective views on issues—views that construct reality in a certain way, leading to different evaluations and recommendations.” Analyzing frames in the media can provide a bigger picture with regard to social developments and processes (Giles and Shaw 2009; Reese 2007; Van Gorp 2007) as well as how frames communicate values and their potential to influence audience understanding and cognition (Ball-Rokeach and Rokeach 1987; Price et al. 1997). In their study of framing and legitimacy of casinos and online gambling, Humphreys and LaTour (2013) also found that media frames can influence cognitive legitimacy. They maintain that frames have the power to direct audience attention to or from particular aspects of an organization, industry, product, or issue. The authors indicate that in so doing, frames may also reveal the fluctuations in legitimacy. In their analysis of British newspaper coverage of climate change from 1985 to 2003, Carvalho and Burgess (2005) showed how the meanings associated with climate change shifted over time; coverage was influenced by social and political developments as well as the publications’ own ethos. They thus concluded that “Values and ideological cultures are key to explain variations in the media’s reinterpretations of scientific knowledge on climate change” (Carvalho and Burgess 2005, p. 1467).

Framing has also proven to be a useful tool in previous studies on nonprofit and nongovernmental organizations (Deacon et al. 1995; Hale 2007; Ihlen et al. 2015). For example, Deacon et al. (1995) research media portrayal of voluntary organizations in Britain; Hale (2007) examines how the portrayal of nonprofit organizations in the media from using agenda setting and framing theories; and Ihlen et al. (2015) investigate how NGOs develop and adapt framing strategies. Prior research on legitimacy and media frames has shown that media evaluations affect normative legitimacy (Deephouse 1996; Zimmerman and Zeitz 2002). However, Humphreys and LaTour (2013) maintain that media frames do not just result in changes to normative evaluations, but can directly impact cognitive evaluations as well. Their research revealed that when the new label “gaming” replaced the old label “gambling,” nongamblers responded positively and “had more associations with the legitimate practice after being shown the new label, “gaming” (Humphreys and LaTour 2013, p. 788). The authors concluded that normative legitimacy judgments had been mediated by cognitive legitimacy. [Note the distinction between the use of the term label by Humphreys and LaTour (2013) and Hsu and Hannan (2005) the former use it in the context of frame name or description, while for the latter the term represents categorical classifications.]

Labeling is part of the categorization process involved in organizational identity formation (Glynn and Navis 2013). Category can be defined as “a conceptual label or set of meanings that are applied to the entity, thereby distilling it into a condensed form” (Glynn and Navis 2013, p. 1126). External audiences need categories to help them make sense of organizations so they can determine what the organizations do and how well they are doing it compared to others in the category or in other categories. Simply stated, categories provide audiences with a frame of reference.

Category membership has implications for both legitimacy and identity. Organizations that belong to a category can be more readily evaluated and talked about, and are therefore more likely to enjoy greater legitimacy than those that do not (Hsu and Hannan 2005). An organization’s identity is formed in part by the category or categories in which it is a member (Glynn and Navis 2013). Additionally, as some categories are more legitimate than others, organizations may try to identify with those whose association brings the most potential benefits (Glynn and Navis 2013). As McKendrick et al. (2003) showed, however, association alone is not enough to secure cognitive legitimacy. Developing—and embedding—a category that resonates with the public is critical in achieving cognitive legitimacy (Kennedy 2008). The media is one vehicle for embeddedness. Inclusion of organizations into a specific category by the media makes them identifiable as a new population (Kennedy 2008). Belonging to a category does not preclude organizational change; however, new categories can emerge as the social context changes, and both firms and audiences can play a role in this process using “cultural narratives, frames, or labels” (Glynn and Navis 2013, p. 1132).

Humphreys (2010) showed how changes in the labels attached to casinos in the media affected industry legitimacy. Once described as places of crime and prostitution, casinos in the United States have more recently become synonymous with entertainment and, in the case of Las Vegas, with luxurious hotspots (Humphreys 2010). The author attributes this change in part to shifts in semantic emphasis in newspaper articles which can both reflect developments in industry legislation as well as reveal topic selection by the journalist. Topic selection impacts cognitive legitimacy in that the existence of a subject in newspaper pages over time creates awareness. The words used to write about the topics influence normative legitimacy as certain aspects are highlighted or particular values are emphasized. Determining what was newsworthy about the organizations and assigning specific words to them impacted organizational identity and legitimacy, and thus helped to change the face of the industry.

Media attention to NGOs has also been a critical part of sector development. The following section will discuss NGO status in the United Nations, NGO proliferation, and their road to taken-for-grantedness.

Nongovernmental Organizations: Definition and Rise

United Nations

The literature is rich with definitions for “nongovernmental organization” (Agg 2006; Florini 2008; Martens 2002; Salamon 1994; Spar and La Mure 2003) making the term both approachable and evasive at the same time. In this study, we use the United Nations’ requirements for consultative status as the defining features of an NGO. Given the governing body’s institutional standing and its role in NGO evolution, this appears to be a logical approach.

Article 71 of the Charter of the United Nations in 1945 marked the beginning of growing use of the term nongovernmental organization internationally. (See Charnovitz 1997 and 2006 for a detailed history of NGOs.)

The Economic and Social Council may make suitable arrangements for consultation with non-governmental organizations which are concerned with matters within its competence. Such arrangements may be made with international organizations and, where appropriate, with national organizations after consultation with the Member of the United Nations concerned.

Although Article 71 recognized that NGOs could play a role at the UN, this role was not clearly elucidated at the time nor was the meaning of nongovernmental organization specified. However, it was stipulated that in order for an NGO to be eligible for consultative status, the organization must be nonprofit, nonviolent, not a school or political party, and not exclusive in its aid (Willetts 2000). Willetts (2002) attributes the use of the term “nongovernmental organization” over alternatives to the term’s generality. We hold that this generality and a common umbrella for a group of diverse organizations ultimately facilitated public categorization and labeling of the organizations, thereby contributing to the cognitive legitimacy of the sector as a whole.

The United Nations not only provided categorical parameters for defining NGOs but also participation in UN conferences conferred regulative and normative legitimacy to the organizations. The 1990s were especially important to the legitimacy process. During this time, NGOs received more recognition from the UN, and the discourse regarding NGO involvement in UN affairs began to change as well. The granting of official observer status to the International Committee of the Red Cross in 1990 was a critical move toward NGO recognition (Willetts 2000). Furthermore, NGO participation in UN conferences led to major stirrings of change (Willetts 2000). The most significant changes occurred during and after Habitat II, the UN conference in Istanbul in 1996, so named for its focus on human settlement and living environment conditions. For the first time, NGOs were officially included in the negotiating process, and the discourse surrounding UN-NGO cooperation moved from one of consultation to partnership (Willetts 2000). In May 2000, the discourse again took another tone when UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan called for even greater NGO participation in global policy: “Today, I am asking you NGOs to be both leaders and partners: where necessary, to lead and inspire governments to live up to your ideals; where appropriate, to work with governments to achieve their goals” (United Nations 2000). The UN was now asking NGOs not just to be partners but to be leaders in pursuit of policy goals as well.

Beginning in 2008, the discourse at the United Nations included aid effectiveness when the UN Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) published “Towards a strengthened framework for aid effectiveness” (Manning 2008), a study commissioned by the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UNDESA). Aid effectiveness had been the subject of the High Level forums in Rome in 2003 and Paris in 2005, but the UN officially put aid effectiveness and civil society accountability on its agenda with documents such as the one in 2008, which was published in preparation for the third High Level Forum held the same year. High Level forums on aid effectiveness are an initiative of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development [OECD], which are cosponsored by, among other institutions, the United Nations and the World Bank, and were established to discuss how to achieve the best results possible from aid funds and programs. They are not official UN events.

The Rise of NGOs

The rise of the NGO has been thoroughly documented by multiple scholars (Boli 2006; Charnovitz 1997; Doh and Guay 2006; Mathews 1997; Salamon 1994; Skjelsbaek 1971; Teegen et al. 2004; Yaziji and Doh 2009). Although estimations as to the specific number of NGOs worldwide vary depending on how the term is defined and who is doing the counting, it has been a growing sector for decades. Figure 1 illustrates this growth from 1909 to 2012, based on statistics published by the Union of International Associations (UIA) in the Yearbook of International Organizations. According to UIA, there were 2795 international NGOs in 1972. This number jumped to 13 768 in 1985, and 16 113 in 1991. In 2005/06, there were 20 928 active, confirmed international NGOs and in 2012 the number rose to 24 310. A brief summary of how and why the rise in NGOs occurred will be provided below as a backdrop for the rest of the article.

Salamon (1994) attributes four crises with initiating the individual, institutional, and government action that fueled the NGO boom: the inability of western states to meet growing social welfare costs; the effects of the oil crisis in early 1970s and the economic recession in the early 1980s on developing countries; increased environmental concerns; and the failure of socialism that was evidenced by economic regression in the mid-1970s. He explains that these crises, combined with technological advances in communication and an economic boom in the 1960s and early 1970s that created middle class leadership in developing countries that would help establish nonprofit organizations in their countries, provided fertile ground for the development of the third sector. He maintains, however, that in 1994, although the NGO movement was growing, NGOs had not yet become “a serious presence in public consciousness, policy circles, the media or scholarly research” (Salamon 1994, p. 121). This is not to say that the public was unaware of individual organizations such as Amnesty International, the Red Cross, and Greenpeace or that no scholarly research on NGOs was being conducted. Yet the term nongovernmental organization and the acronym NGO were not yet widely known among the public nor was the public aware of an NGO sector.

Doh and Teegen (2002) state that NGO involvement in the antiapartheid movement in South Africa in the 1980s marked the entrance of NGOs as significant players in the international business arena. McGann and Johnstone (2006, p. 66) list the key events in the NGO “revolution” as the political transformation in Poland in the 1980s, the 1992 Earth Summit, the 1994 “Fifty Years is Enough” campaign, and the 1999 World Trade Organization protests in Seattle. While scholars may not agree upon which specific events influenced the NGO move to the global stage, the combination of these events led to the NGO period of “empowerment” that began in the 1990s (Charnovitz 1997).

NGO newspaper exposure also began to rise in the 1990s which experts attribute to a number of factors. Ron et al. (2005) attribute the rise to more strategic, assertive media campaigns, citing Amnesty International’s increase in press releases in 1993. Chandler (2001) charges that the media surge was due to a transition in the provision of humanitarian relief from a nonpolitical standpoint to one that was focused on influencing policy and behavior. He states that NGOs sought the press to advocate their causes and the press was eager to report on shocking stories and anguished victims. Keck and Sikkink (1999) credit NGO success in the 1990s to the rise of transnational advocacy networks. The sharing of funds, personnel, information, and services allowed the networks to more effectively and extensively publicize and act on specific issues throughout the world (Keck and Sikkink 1999; Sikkink 1993). Bimber et al. (2005) maintain that developments in internet-based communication technologies (ICT) changed the face of collective action by allowing people from various backgrounds and geographical regions to connect and organize quickly and relatively cheaply.

The change in NGO status at the UN, continued growth in numbers, intra and interorganizational collaboration, and increased and more assertive communication appear to be part of a larger institutional shift that resulted in meaningful consequences for NGO legitimacy. Also fundamental to the legitimacy process was a general understanding of what NGOs are and what they do, and a common category label with which to identify them (McKendrick and Carroll 2001). One of the vehicles to communicate and embed this category and identity, and therefore increase NGO legitimacy, was print media. In the following section, we will explain how we analyzed the proliferation of the term nongovernmental organization and how the newspaper discourse about NGOs changed from 1985 to 2010.

Method

Data Collection

A content analysis of two English language newspapers was conducted for the period 1985–2010. In the analysis, we focus on the category “nongovernmental organizations” in an international context. As previously discussed, categories increase recognition of a group of organizations as belonging to a particular from and thus raise audience cognition (Hsu and Hannan 2005).

The newspapers used in the study—the New York Times and the Financial Times—were selected based on region, circulation, and agenda-setting capacity. According to a 2011 European Media & Marketing Survey (EMS) conducted by Synovate Research Group, the Financial Times was the number one international brand in Europe for daily print and web usage combined (“No. 1” 2011). A 2011 study conducted by ComScore, an independent digital survey company, indicated that The New York Times was the number one ranking global online newspaper (Durrani 2011). In addition, the two newspapers are considered elite media outlets which can both reflect and impact legitimacy (Deegan et al. 2002; Deephouse and Suchman 2008; Vergne 2011). They have the ability to set the agenda for policy makers and the public (Carvalho and Burgess 2005; Holt and Barkemeyer 2010; Islam and Deegan 2010; Jordan 1993; Mazur and Lee 1993) as well as other news sources (Nisbet and Huge 2006). Thus, although the newspapers may cater to a different readership and present a different focus—‘center, right business’ versus ‘liberal news story and editorial’—they were chosen for this study due to their agenda-setting capacity. Moreover, as previously indicated, media accounts reflect the development of cognitive legitimacy (Baum and Powell 1995; Dowling and Pfeffer 1975; Hannan et al. 1995; Humphreys and LaTour 2013) and are therefore useful in studies of organizational legitimacy (Deephouse and Suchman 2008).

A keyword search in the LexisNexis archive was conducted for the search terms “nongovernmental organi*ation”—the asterisk representing either an “s” or “z”—from 1985 to 2010. Both “non-governmental” and “non governmental” resulted in substantially fewer hits in both newspapers, while “nongovernmental organization” resulted in more hits and included the articles which appeared for the other search terms. A total of 1611 articles were found in the New York Times and 3152 articles in the Financial Times. The purpose was to determine how many articles included the search term nongovernmental organi*ation and not the number of times the term was used in total. In addition, it is important to note that letters to the editor and obituaries were included. The reason for this is that we are studying the categorization, labeling, and legitimacy of a sector. Being named and referred to in either of these contexts is still appropriate to this research given increased salience. Mazur (2009) maintains that quantity can have greater audience impact than content. We chose 1985 as a begin date for the study for practical reasons. Given the focus in the academic literature on the 1990s, we wanted to go back at least five years prior to 1990 to determine what, if any, the trend in the newspapers might be. Also, the LexisNexis archive of the Financial Times begins in 1982 so we were unable to access earlier files via the database.

A LexisNexis search of the following terms was also conducted: relief agency, aid agency, voluntary organization, volunteer organization, humanitarian organization, nonprofit organization, non-profit organization, not-for-profit organization, charitable organization, and international nonprofit organization. The objective of this search was to confirm whether or not “nongovernmental organization” was the most appropriate term for the organizations we are seeking to research in the media. All of the terms above produced too few hits to be representative or included organizations beyond the scope of this study. For example, a search of the term “nonprofit organization” resulted in more hits than other terms, but included national and regional organizations dedicated to any number of causes from the arts to athletic activities. Hence, this term was not compatible with our definition of NGO. The terms relief agency and aid agency came close to our definition, but a search of these terms also included articles on governmental relief and aid agencies at national and regional levels; this does not meet our criteria of nongovernmental. Other terms in the search included voluntary organization, volunteer organization, international nonprofit organization, not-for-profit organization, charitable organization, and humanitarian organization. Of these terms, voluntary organization seemed to come closest to what we call international NGOs, but the number of hits was not significant.

In addition to mapping term frequency, we also randomly selected a sample of 357 articles from the total number of articles between 1985 and 2010 and analyzed them using a framing tool. Given this total, a sample size of 357 was necessary in order to be 95 % confident that the population percentage is within 5 % of what we find in the sample (Neuendorf 2002, p. 89). The original sample consisted of 396 articles and included 56 articles (47 in the FT and 9 in the NYT) regarding quasi nongovernmental organizations (quango) or quasi-governmental organizations. Given that quangos are a highly contested issue in the UK, the prevalence of articles about them was greater in the FT than the NYT. The sample was first coded with the quango and quasi-governmental articles, but due to issues of politics and autonomy related to the organizations, we chose to exclude them (see Greve et al. 1999). The number of articles coded per newspaper per year was determined using a ratio of sum-to-total.

It is also important to analyze the growth pattern in the number of articles about NGOs. A common characterization of changes in the number of articles dealing with NGOs, as shown in Fig. 2, seems to support the idea that the occurrence of the term nongovernmental organization follows a trend line with a positive slope over the 26-year period. We also statistically analyzed the number of articles on NGOs in the Financial Times and the New York Times, separately and combined, for the period 1985–2010. The relatively short time series implies that our econometric models have to remain quite basic (Hagedoorn and Van Kranenburg 2003).

The data in Fig. 2 were subjected to regression analyses and curve fitting in order to see what patterns, linear and curvilinear, could be found. We analyzed patterns for three regression models. In the regression analyses, we focus on the amount of variance explained, adjusted R 2. Adjusted R 2 considers the amount of variation, 0–100, that is explained by the patterns in the number of articles over the time period. It takes into account sample size as well as the number of predictors in the regression model (Field 2009, pp. 221–222). As time series data are prone to autocorrelation, which means that observations are dependent because of the time lag between them, we used the Prais–Winsten estimation method to correct for this (Wooldridge 2013). We reported regression results after Prais-Winsten correction including the Durbin–Watson statistic as a measure for autocorrelation (Durbin-Watson values range from 0 to 4, values close to 2 indicate absence of serial correlation; see Field 2009, pp. 220–221). To check if the strength of the relationships differed, we compared the unstandardized regression coefficients of the Financial Times and New York Times articles (Paternoster et al. 1998). Finally, by means of curve fitting, we checked which approach (linear, quadratic, cubic) explained most of the variance in the data. In this we followed the principle of parsimony in which simple curves are preferred over more complex ones.

Coding

The articles were coded using a frame identification system based on De Souza (2010) who identified the following frames as relevant for NGOs: Do Good, Protest, Partner, and Public Accountability. Where an article appeared to contain more than one frame, the dominant frame—based upon article context—was documented. Specific words and phrases were cataloged to substantiate frame selection.

Because assigning the articles to the most appropriate frame is critical to the research, it is useful to define the frames in more detail. The Do Good frame focuses on important, productive work that NGOs have done in recognizing and reducing societal problems. The Protest frame includes articles that involve NGOs speaking out against government or business activity that they deem unethical, harmful, irresponsible, illegal, or threatening. Articles assigned to the Partner frame highlight collaboration with government and other sectors. The Public Accountability frame questions NGO activity, specifically concerning issues such as corruption, accountability, and poor management.

After an initial trial of coding using these frames, it became clear that additional frames were needed in order to more adequately capture the discourse. To the frames above, we added Expert, Government Resistance, and Other. Expert was used when NGOs were interviewed for their view on a subject or provided information. Government Resistance was used when the context in which the NGO was discussed had to do with limiting NGO rights in a particular country because a national government was skeptical of the NGO’s operations and/or concerned about NGO intentions. “Other” was marked when the term nongovernmental organization was mentioned, but the context did not meet any of the other frame criteria. That being said, the mere mention of nongovernmental organization points to increased media salience and thus cognitive recognition (Hsu and Hannan 2005; Kiousis 2011; McCombs and Shaw 1972).

When the final coding tool was completed, the tool was tested for reliability using a sample of 136 articles. The articles were coded by the first author and a colleague not participating in the project. Where there was a discrepancy in the codes, the coders discussed the articles and reached agreement, following a consensus-coding approach (Gibbert and Ruigrok 2010). Intercoder reliability of the preconsensus codes was 86 % (kappa: .53, indicating fair agreement; see Fleiss et al. 2003). During the coding process, the first author tested for coder drift two months after the original coding by randomly selecting 30 articles from the sample and recoding them. This resulted in a 97 % agreement rate.

The research combines deductive and inductive approaches to our analysis. For example, we begin with a quantitative analysis informed by legitimacy theory and the concepts of density dependence and identity. This analysis alone did not provide sufficient information regarding the development of nongovernmental legitimacy. We therefore also conducted frame analysis using an existing framework. When we found frames in the data that were not represented, we added them to reflect what was discovered in the data set. As Hennink et al. (2011) indicate, the analysis process is circular rather than linear and developing explanations and verifying them involves moving back and forth through the data, literature, and theory. The final four NGO frames were arrived at inductively through this process.

Results

A search of related terms revealed that “nongovernmental organization” was indeed the most appropriate term for us to use in this research. Not only is nongovernmental organization the term used in United Nations documents and communications (see Willetts 2000), but it also proved to be the narrowest of the terms available.

From 1985 to 2010, the term was mentioned in the New York Times in 1611 articles compared to 3152 in the Financial Times (after correcting for quangos and quasi-governmental organizations). The search showed that from 1985 to 2010 stories including the term “nongovernmental organization” increased considerably in both the New York Times and the Financial Times (see Fig. 2). Despite the difference in numbers of articles in the newspapers, the graph profiles showing the number of articles over time are quite similar. Mentions in the New York Times and the Financial Times declined dramatically after 2005 and 2006, respectively, and had not yet returned to their 2006 level in 2010. In the New York Times in 1985, the term “nongovernmental organization” appeared in 21 articles. By 1999, this would increase to 53. Coverage reached a peak in 2005 at 127 articles, and dropped to 111 in 2010. In the Financial Times, there were 6 articles in 1985, and 200 in 1999. A peak of 310 mentions was reached in 2006; this dropped to 115 in 2010. We found very little reference to the term nongovernmental organization in the newspapers in 1985, followed by a surge in the 1990s, a peak in the middle 2000s, and a decline of mentions thereafter.

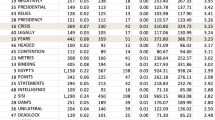

Table 1 shows the results of the regression analyses revealing that for the Financial Times, New York Times, and both newspapers combined there was a statistical significant model indicating a linear relationship in the number of articles on NGOs in the period 1985–2010. After Prais-Winsten correction, the Durbin-Watson statistic for the New York Times was closer to the value of 2 (indicating absence of autocorrelation), than for the Financial Times and for the newspapers combined. However, the data did not seem to indicate very serious problems regarding serial correlation (as values were not below 1). The data for the New York Times better fit a linear curve than the data for the Financial Times (as appears from R2 values in Table 1). However, comparison of the unstandardized regression coefficients did not reveal a difference in the regression slopes for the newspapers (Z = .790, p = .43). Curve fitting analyses showed, in general, that higher order curves (quadratic, cubic, power) or other curves (logarithmic, S-shaped, growth, exponential, logistic) did not substantially improve the amount of variance explained (in terms of adjusted R 2) in comparison to a linear curve (statistics withheld). All in all, the quantitative analyses indicated that there was a linear increase in the number of articles on NGOs in both the Financial Times and New York Times meaning that NGOs received more and more media coverage (resulting in greater public awareness) in the period 1985–2010.

As previously mentioned, the articles were coded using a framing tool. Table 2 shows the total results, and Table 3 shows the results in the time periods listed below. The time periods reflect the regulatory structure that was shaped by the United Nations; the newspaper articles echo the changes in these structures (Humphreys 2010) and thus the transitions in NGO legitimacy.

Tables 2 and 3 show the framing results of our sample of the Financial Times (FT) and New York Times (NYT) articles. The “Do Good” frame was the dominant frame overall and remained stable in all time periods. From 1992 to 1999, the partner frame began to develop. For the period 2000–2007, “Partner” and “Expert” became important themes. The figures show that the Do Good, Partner, and Expert frames were the most common over time (31, 16, and 18 %, respectively).

A Chi-square analysis revealed that there were statistically significant differences (χ 2(6, n = 357) = 37.0, p < .001) in the frames used in the Financial Times and New York Times during the 1985–2010 period. The number of “Do Good” frames was relatively higher in the NYT than in the FT, whereas the “Protest” and “Accountability” frames occurred more often in the FT than in the NYT. The occurrence of the other frames did not differ between the two newspapers.

Media attention to nongovernmental organizations as a sector has thus been predominantly positive over time. Given the financial crisis and the UN aid effectiveness discourse that began in 2008, we expected to see more articles in the public accountability frame between 2008 and 2010. The relatively few articles in this frame might be attributable to our sample size or the short span of three years in the final time period.

Further analysis of the frames resulted in four main categories and time periods that represent the broader changes (Boeije 2010) in the depiction of NGOs in the newspapers over time. The categories include Protectors, Partners, Policymakers, and Providers. The data showed that until 1991, NGOs were viewed mainly as what we term Protectors—individual organizations that deliver aid and advocacy. From 1992 to 1999, they became Partners, having gained increasing influence among international organizations. From 2000 to 2007, NGO involvement in government and business affairs continued to grow, as did their hand in policymaking. Beginning in 2008, aid effectiveness became a key theme at intergovernmental organizations such as the UN, OECD, and World Bank. While NGOs still retain significant influence, the shift from Policymaker to Provider of aid began to take place at this time. The categories reflect incremental shifts in the role of NGOs as depicted in the newspapers and the literature during the period 1985–2010, with perhaps the most striking shift taking place during the period 2000–2007 when the focus moved from NGOs as partners to NGOs as policymakers. Table 4 presents an overview of the shifts in framing. Examples of these shifts are provided in the newspaper excerpts below.

Our findings show that in 1985 when the term nongovernmental organization was used in an article in the NYT and the FT, it was often used in the context of the organization doing something good for society, either providing aid that government could not or delivering aid more successfully than government:

Local problems should be solved by local people, but the nongovernmental organizations are necessary because governments are not giving us what we need (Crossette 1991, NYT).

Small nongovernmental organisations whose representatives have reached the affected areas have proved to be more effective than the official machinery (Ahmed and Sharma 1991, FT).

Between 1985 and 1991, NGOs were generally referred to positively in the media. They were viewed as peripheral groups providing humanitarian aid and advocating for human rights and environmental reform. They challenged existing policies, but they were not yet widely viewed as partners in reform the process.

The newspapers reveal that from 1992 to 1999, NGOs came to be represented as partners, working closely with governmental and international agencies. This also marked the beginning of an NGO move toward a greater role in policy making in the provision of aid. For instance, in an article entitled “The U.N. at 50: Facing the Task of Reinventing Itself,” in the New York Times, “greater representation of nongovernmental organizations” is listed as one of the changes taking place within the United Nations (Crossette 1995, p. 1). Another article reported that “One reason Western governments have turned to partnerships with nongovernmental organizations is that they are seen to be best placed to facilitate the bottom-up development that is key to reducing poverty” (Turnipseed 1996, NYT).

These passages reflect the growing influence of NGOs in the regulatory arena, and a switch from NGOs as individual activist organizations to NGOs as a group, as partners. “NGO” was still not a well-known acronym among the general public; however, it would still take time for “NGO” and “nongovernmental organization” to become household names as the identity labels for the industry. For example, in a report on Hillary Clinton’s speech at the United Nations Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing, William Safire wrote the following:

Her use of NGO’s, an abbreviation, before using the full phrase, “nongovernmental organizations,” invited confusion in the minds of the worldwide audience; it’s not a good idea to assume everyone knows what the local audience does. There are those for whom NGO stands for Nongovernmental Observers, Naval Gunfire Officer or National Gas Outlet (Safire 1995, NYT).

Although NGOs were still not a household name, in 1998 the New York Times reported a turning point in world polity and the place of NGOs therein:

To some, the growing role of private companies and nongovernmental organizations, or N.G.O.’s as they are known, in foreign policy marks a jaw-dropping transformation in the world’s political structure (Lewis 1998, NYT).

The following passage evokes the growing awareness of NGO economic and political influence, and also as welling concern about the extent of their involvement. The terms NGO and nongovernmental organization are also emphasized in the previous and following excerpts.

Their numbers have mushroomed in recent years, their spending has soared, and their political influence is steadily growing. They are the NGOs—non-governmental organisations, a multi-billion dollar industry, on the front line of Africa’s many conflicts, and at the heart of the continent’s battle for economic recovery. Some African governments fear that they are becoming the new colonists of the developing world (Holman 1999, FT).

Between 2000 and 2007, the newspapers indicate that NGO involvement in world polity reached new heights. Leading functions at key global events, soaring financial resources and economic power, and recognition by business of the global reach of NGO influence all point to a time of transition for the organizations:

De Beers is not alone in acknowledging the power of the nongovernmental organizations. This year, both the United Nations and the World Economic forum in Davos, Switzerland, recognized the organizations’ role, conferring a new legitimacy as many corporations move from confrontation to at least the appearance of cooperation with them (Cowell 2000, NYT).

Increasingly, they are operating from the inside by working closely with governments, especially from developing countries, to offer research, public relations resources and even help with the detailed drafting of negotiating proposals (de Jonquieres and Williams 2001, FT).

The expectations of NGOs were growing, but so too was trepidation as to whether continued aid might be solving short-term problems but creating long-term reliance. NGOs were no longer simply empowered by society and other organizations to fulfill a role in global social welfare, but rather in many cases they were being expected to do so.

Meeting such expectations and staying in business in an environment in which thousands of NGOs are competing for resources resulted in unexpected alliances with business. In 2004, the Financial Times quoted the Executive Director of Greenpeace UK as stating the following on the subject of the organization’s alliances with Unilever and the electricity company NPower:

We think (alliances) are essential to unlocking progress… The more unusual the alliance, the more effective it is likely to be. Greenpeace is interested in who has the power to make change, rather than simply being an outside group and protesting (Maitland 2004, p. 7).

Alliances between Oxfam and Starbucks, Chiquita and Rainforest Alliance, and Save the Children and Ikea are also mentioned in the article, citing “money, technology and influence” as partnership incentives for the NGOs.

The period 2006–2009 saw a considerable rise in growing suspicion by mainly nonwestern governments that the NGO agenda may be politically motivated. Stories on Russia rose substantially in the New York Times in 2006 as Putin began to impose more regulations on foreign NGOs. New York Times reporters also covered stories in 2006 about negative pressure and/or government restriction on NGO activities in Iran, China, Venezuela, Kazakhstan, and Afghanistan. Viewing NGOs as political arms of foreign governments began to hinder or halt foreign-funded NGO activities.

Not only were national governments questioning the independence and increasingly governmental nature of NGOs, but so too were experts in the field. For instance, in a letter to the editor on 16 June 2006, Richard Walden, then President and Chief Executive of Operation USA, stated that “Reimbursement by government and United Nations agencies has created a contracting—not a charity—mentality among relief agencies” (Walden 2006, NYT). This example signals a change in reporting on NGOs to an increasing awareness of accountability. For instance, one article in 2006 was titled “Accountability and Ethics: Billions of dollars of aid to Africa has had minimal effect” and reported on calls for more NGO and aid organization accountability (Jack 2006, FT). Another article in 2007 talked about the professionalism and focus on accountability of the aid industry (“Charities look,” 2007, FT). Our sample shows that most articles from 2000 to 2007 were about NGOs as experts, partners, or doing good, but it is important to note that accountability and change were also part of the discussion at this time.

In 2008, aid effectiveness became a dominant theme in the NGO discussion. A Financial Times story in 2008 entitled “Charity begins in the office” (Murray 2008) focuses on the issue of efficient aid administration and the use of online systems that simplify reporting for NGOs and allow donors to track the management of resources.

The reporting in the New York Times on the 2010 earthquake in Haiti also highlights accountability issues and the effectiveness of aid. While former U.S. president Bill Clinton co-authored articles that called on the public, business, and government to donate funds and coordinate efforts (Bellerive and Clinton 2010; Clinton and Bush 2010), New York Times columnist David Brooks argued that the long-term solution for countries like Haiti should not be continued donor aid. In his words, “we don’t know how to use aid to reduce poverty” (Brooks 2010, p. 27). He acknowledges the efforts of the relief workers, but indicates that empowering local leaders to enact change is the only long-term solution in a country that has received millions of dollars in aid and “has more nongovernmental organizations per capita than any other place on earth,” yet still lacks the infrastructure and services to govern independently (p. 27).

The articles in the New York Times and the Financial Times from 1985 to 2010 suggest a changing landscape between sectors, as well as public concern regarding NGO practices and the provision of aid. The change in NGO frames from protectors to partners to policymakers was fairly straightforward in the newspaper accounts. The focus on aid effectiveness beginning in 2008 suggests a dominant view of NGOs as aid providers, with a particular emphasis on the efficacy of that provision.

Conclusion and Discussion

The aim of this study was to determine when NGOs acquired taken-for-granted legitimacy and how this was reflected in the media. To that end, a longitudinal study of media coverage of nongovernmental organizations was conducted and the implications of this coverage on organizational legitimacy were analyzed. We were able to show the importance of categories and labels to organizational identity formation and sector legitimacy (Hsu and Hannan 2005). A framing approach to media coverage of nongovernmental organizations revealed changes in the public understanding of NGOs, and thus changes in the general culture as well (Van Gorp 2007). This paper contributes to the literature on nongovernmental organizations by showing when the public became aware of the organizations as a sector, the importance of “nongovernmental organization” as an identifying label, and changes in the way NGOs have been discussed in newspapers over time. The study resulted in a number of findings about nongovernmental organizations that to the best of our knowledge have not been previously reported.

First, our evidence shows that the use of the term nongovernmental organization became more popular in the Financial Times and the New York Times in the 1990s. Although its definition has been a source of contention in the literature, “nongovernmental organization” appears to be the category with the most cognitive staying power. While other terms are being used in the media and elsewhere, nongovernmental organization still seems to be the preferred nomenclature to describe the sector and the entities in the sector.

Second, our statistical analyses showed a linear trend in the number of articles that mention NGOs in both the Financial Times and New York Times. We can thus infer that given that the media serve to disseminate information (Hannan et al. 1995), NGO legitimacy as an organizational form did not occur in a vacuum. Although the newspapers cover two different institutional contexts—the US and Europe—increased legitimation appears to have occurred simultaneously which we can see in the jump in activity in both newspapers in the early 1990s. The institutional contexts do appear to play a role in the number of articles each paper devoted to the subject; there were considerably more mentions in the Financial Times than the New York Times from the 1990s until 2011 (the difference was not significant during the period 1980–1989). This difference might be explained by “an institutional setting more receptive to arguments and tactics of non-governmental advocacy” in the European Union (Doh and Guay 2006, p. 66), but additional research would need to be conducted to determine this conclusively.

Third, we found that while NGOs had been operating for decades and had been formally recognized by the UN since 1945, cognitive symbols—“words, signs, and gestures” (Hoffman 1999, p. 353)—related to this organizational form began to develop and flourish in the 1990s. Scholars refer to the 1990s as the NGO “heyday” or “revolution” despite the fact that the largest jump in the number of these organizations occurred a decade earlier. An increase in organizational density alone can thus not explain the increase in cognitive legitimacy (McKendrick et al. 2003). Only when relief, humanitarian, and advocacy organizations were categorized and came to be known by the general public as “nongovernmental organizations,” did NGOs begin to achieve taken-for-grantedness as a sector. Embeddedness of the term in the media was critical to this process (Kennedy 2008). The power and influence that NGOs know today can in part be attributed to the collective identity that was established in the 1990s, with the tipping point occurring around 1996. Increased recognition by the United Nations in formal declarations, a changing NGO–media relationship, NGO partnership and collaboration, and the rise of the use of “nongovernmental organization” in print media helped to create and propagate the cognitive legitimacy of the sector. The establishment of a distinct category served to propel cognitive recognition and thus increase the legitimacy of the organizations (McKendrick and Carroll 2001).

Fourth, nongovernmental organizations were primarily represented as “doing good” in the Financial Times and New York Times from 1985 to 2010. In his study of U.S. nonprofit organizations, Hale (2007) also found that media coverage of nonprofits was generally positive. Given that positive coverage is an indicator of legitimacy (Deephouse 1996) and that legitimacy is linked to resource attainment (Suchman 1995), media representation remains consequential to the organizations.

Fifth, media framing has played an important role in the legitimacy process of NGOs. Topic selection in the newspapers leads to greater cognition, and semantic categories reflect normative judgments (Humphreys 2010). At the same time, what gets printed may also have to conform to the values of the publication (Carvalho and Burgess 2005). If specific labels are selected over others, public understanding can be influenced over time. Our findings show that although the category “nongovernmental organization” has remained the same, our understanding of these organizations has changed and this change can be detected through frame analysis of newspaper articles (Pollock and Rindova 2003). For example, Agg (2006) indicated that the “golden age” of the NGO may be over. We maintain that it is no coincidence that at the time of Agg’s study, NGO accountability and effectiveness began to enter the main discourse. However, it should be noted that our findings regarding the Provider frame were mixed. When all articles during this period were considered, we found many examples of accountability and aid effectiveness. Our sample, however, did not turn up as many articles in this frame as we had expected. As indicated above, this may be attributable to the fact that the study ended in 2010 and thus resulted in a frame of only three years. We expect that the Provider frame—and focus on aid effectiveness—continued beyond that time, but further analysis would be necessary to confirm this.

Finally, during the early 1990s and middle 2000s, the term nongovernmental organization helped to identify these organizations as a unified group, and that term stood for partner and policymaker. The end of the golden age signaled a focus on NGO efficaciousness as providers of aid. While NGOs are still partnering with business and government and are involved in policy development, their status has not been able to protect them from public scrutiny in the age of accountability. A combination of institutional and discursive factors resulted in changes in the way NGOs were framed in the newspapers, from protector to partner to policymaker to aid provider. Media attention alone does not determine legitimacy, but it contributes to the legitimacy process by embedding meaning through categories and understanding through frames.

The implication for NGOs of the findings presented here is that not only media attention to individual organizations is important to organizational legitimacy, but also the way that the sector is framed as a whole can impact legitimacy and therefore access to resources. How the organizations—as an industry or as smaller groups of networked organizations—strategically approach the current dominant frame of aid effectiveness could significantly impact both the legitimacy and identity of the sector.

The 1990s marked the beginning of taken-for-granted legitimation of nongovernmental organizations as a sector. The current aid effectiveness discourse reflects growing concerns about accountability as well as an environment in which competition for funds requires organizations to meet donor demands and show their performance outputs. Some praise these developments and increased cooperation with business (e.g., Yaziji and Doh 2009), while others indicate that donor-driven activity and a focus on measurements undermine the purpose of the sector (e.g., Banks et al. 2015). Sometimes maintaining legitimacy with one stakeholder may mean a loss of legitimacy with another. For instance, implementing donor performance and accountability procedures may serve to maintain legitimacy with donors, but it may decrease legitimacy with constituents or the general public who may view such cooperation as compromising the organization’s integrity and independence. However, not implementing such procedures could lead to a loss of funding that is critical to organization survival. We believe this Catch-22 could affect NGO identity in that organizations similar to one another may choose to splinter off and seek a new category or label that better represents them and the interests of their stakeholders, and distances them from threats to their legitimacy.

With regard to limitations of this study, we analyze an increase in cognitive legitimacy using two western newspapers. Although the New York Times and Financial Times are considered agenda-setting publications, generalizability could be improved through the use of more newspapers or media outlets. This study is a first step in an attempt to provide evidence concerning the statistical properties of a time series of newspaper articles dealing with NGOs that may be susceptible to systematic interpretation. Our econometric models provide a basic understanding of the movement of published newspaper articles. Future studies can develop a range of additional models that provide further understanding of the growth pattern in media attention.

Another limitation of the study was the relatively small sample size of coded articles. Although the sample was large enough to be 95 % representative of the data population (Neuendorf 2002), a larger sample might show the patterns more distinctly. The coding scheme was also rather cumbersome to work with; future studies might modify or simplify the scheme to make it an easier tool with which to work. Additionally, the study does not provide causal evidence for the peak of coverage in the middle 2000s; whether events such as the 2004 tsunami across Indonesia or Hurricane Katrina and the Kyoto Protocol in 2005 resulted in peaks in news coverage attention cycles (Holt and Barkemeyer 2010) might be a topic for future research.

The research presented here focuses on NGOs as a sector, but another study might analyze specific NGOs to gain more perspective on the legitimation process from a within the organization. Finally, the subject of legitimacy here also opens the door to a discursive discussion concerning NGO institutional evolution and change.

Appendix 1: Newspaper Article References

Financial Times

Ahmed, R., and Sharma, K. K. (1991, May 9). “Bangladesh cyclone relief effort delayed by snags.” Financial Times, Overseas News, p. 4.

“Charities look to businesses: NGO evolution.” (2007, July 5). Financial Times, FT Report, p. 4.

Holman, M. (1999, August 19). “The ‘fireman’ flourish in the heat of Africa: NGOs flourish in disaster areas, but some are questioning their influence.” Financial Times, International, p. 4.

Jack, A. (2006, November 16). “Accountability and Ethics: Billions of dollars of aid to Africa has had minimal effect.” Financial Times, FT Report, p. 4.

Jonquieres de, G., and Williams, F. (2001, November 12). “Global activists adopt new tactics: Switch to behind the scenes influence.” Financial Times, World News, p. 10.

Maitland, A. (2004, December 24). “Old foes share common ground.” Financial Times, Business Life, p. 7.

Murray, S. (2008, November 11). “Charity begins in the office.” Financial Times, Wealth, p. 8.

New York Times

Bellerive, J. and Clinton, B. (2010, July 12). “Finishing Haiti’s unfinished work.” New York Times, p. A19.

Brooks, D. (2010, January 15). “The underlying tragedy.” New York Times, p. A27.

Clinton, B., and Bush, G. W. (2010, January 17). “A helping hand for Haiti.” New York Times, p. WK10.

Cowell, A. (2000, December 18). “Advocates gain ground in a globalized era.” New York Times, p. C19.

Crossette, B. (1991, August 6). “Village committees learn to guard endangered forest in Bangladesh.” New York Times, p. C4.

Crossette, B. (1995, October 22). “The U.N. at 50: Facing the task of reinventing itself.” New York Times, Sect. 1, p. 1.

Lewis, P. (1998, November 28). “Not just governments make war or peace.” New York Times, p. B9.

Safire, W. (1995, October 1). “Hillary Speaks.” New York Times, Sect. 6, p. 28.

Turnipseed, R. L. (1996, April 16). “Foreign aid makes a visible difference.” New York Times, p. A20.

Walden, R. M. (2006, June 16). “So how much help is foreign aid?” New York Times, p. A30.

Appendix 2: Coding Guidelines and Examples

Coding Guidelines

The guidelines below were followed by the first author and the independent coder.

-

1)

Determining the frame: Do Good, Protest, Partner, Public Accountability, Expert, Government Resistance, Other*.

-

a)

Do Good: Describes the useful work NGOs are doing; positive statements about NGOs.

-

b)

Protest: NGO activity is mainly described in the article as speaking out—in the form of making an issue public, lobbying, legal action—about unethical, harmful, irresponsible, illegal, and/or threatening practices on the part of government or business.

-

c)

Partner: Collaboration with government, business, or other organizations is highlighted.

-

d)

Public Accountability/Credibility: “NGOs are criticized for corruption, lack of accountability, hidden agendas, and bad management skills” (de Souza 2010, p. 487). Articles in which NGO credibility, effectiveness, or purpose is questioned by constituency other than government (by journalist, expert, citizen, etc.).

-

e)

Expert: Is the NGO or NGO representative being quoted as an expert on the subject? (This category was not part of De Souza’s research)

-

f)

Government Resistance: Government against or negative toward NGO involvement (This category was not part of De Souza’s research).

-

g)

Other: Does not meet any of the above.

-

a)

Coding Examples

Date | LexisNexis article # | Headline | Section | # words | Author | Do good | Protest partner | Public acct.* | Expert | Govt. resist.** | Other | Excerpt from text |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Financial Times | ||||||||||||

22 October 1994 | 42 | More heat than light in Nepal over power wrangle | p. 3 | 870 | F. Gray | X | The government scheme is being strenuously opposed by such nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) as the US-based Environmental Defence Fund | |||||

26 June 2003 | 136 | Accountability ‘vital’ if NGOs are to retain trust | Asia–Pacific | 328 | A. Maitland | X | International NonGovermental Organizations must practice what they preach and become more accountable… | |||||

3 October 2006 | 91 | Air deal founders on US bid to keep clients’ data | International Economy, p. 10 | 391 | A. Bounds, D. Cameron, H. Williamson | X | ``Any individual could challenge this and ask the US how data has been used,’’ said Tony Bunyan, editor of Statewatch, a UK non-governmental organization that monitors civil liberties | |||||

New York Times | ||||||||||||

5 June 1989 | 16 | Kampala Journal; When the trouble is men, women help women | Sect. A, p. 4, col. 3, Foreign Desk | 1000 | J. Perlez | X | There is a lively nongovernmental organization, recently started by women, to help the country’s countless children orphaned by either the civil war or the AIDS epidemic | |||||

2 December 1994 | 5 | Paris meeting backs UN program to combat AIDS | Sect. A, p. 12, col. 1, Foreign Desk | 626 | A. Riding | X | We’re talking about a whole new partnership with non governmental organizations and with people with AIDS | |||||

31 March 2009 | 80 | Obama urges Sudan to allow aid groups back into the country | Sect. A, p. 12, col. 0, Foreign Desk | 413 | P. Baker | X | Bashir responded by expelling 13 nongovernmental organizations | |||||

References

Agg, C. (2006). Trends in government support for non-governmental organizations: Is the “Golden Age” of the NGO behind us? United Nations Research Institute for Social Development (UNRISD). Retrieved from http://www.unrisd.org

Aldrich, H., & Fiol, C. M. (1994). Fools rush in: The institutional context of industry creation. Academy of Management Review, 19(4), 645–670.

Andrews, K. T., & Caren, N. (2010). Making the news: Movement organizations, media attention, and the public agenda. American Sociological Review, 75(6), 841–866.

Ashforth, B., & Gibbs, B. (1990). The double-edge of organizational legitimation. Organization Science, 1(2), 177–194.

Ball-Rokeach, S., & Rokeach, M. (1987). Contribution to the future study of public opinion: A symposium. Public Opinion Quarterly, 51, S184–S185.

Banks, N., Hulme, D., & Edwards, M. (2015). NGOs, states, and donors revisited: Still too close for comfort? World Development, 66, 707–718.

Baum, J. A. C., & Powell, W. W. (1995). Cultivating an institutional ecology of organizations: Comment on Hannan, Carroll, Dundon, and Torres. American Sociological Review, 60(4), 529–538.

Bimber, B., Flanagin, A. J., & Stohl, C. (2005). Reconceptualizing collective action in the contemporary media environment. Communication Theory, 15(4), 365–388.

Bitektine, A. (2011). Toward a theory of social judgments of organizations: The case of legitimacy, reputation, and status. Academy of Management Review, 36(1), 151–179.

Boeije, H. (2010). Analysis in qualitative research. London: Sage.

Boli, J. (2006). International Nongovernmental Organizations. In W. R. Powell & R. Steinberg (Eds.), The non-profit sector (pp. 333–351). New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Boli, J., & Thomas, G. (1997). World culture in the world polity: A century of international non-governmental organization. American Sociological Review, 62(2), 171–190.

Carroll, G. R., & Hannan, M. T. (1989). Density dependence in the evolution of populations of newspaper organizations. American Sociological Review, 54(4), 524–541.

Carvalho, A., & Burgess, J. (2005). Cultural circuits of climate change in UK broadsheet newspapers, 1985–2003. Risk Analysis, 25, 1457–1469.

Chandler, D. (2001). The road to military humanitarianism: How the human rights NGOs shaped a new humanitarian agenda. Human Rights Quarterly, 23, 678–700.

Charnovitz, S. (1997). Two centuries of participation: NGOs and International governance. Michigan Journal of International Law, 18(2), 183–286.

Charnovitz, S. (2006). Nongovernmental Organizations and International Law. American Society of International Law, 100(2), 348–372.

De Souza, R. (2010). NGOs I India’s elite newspapers: A framing analysis. Asian Journal of Communication, 20(4), 477–493.

Deacon, D., Fenton, N., & Walker, B. (1995). Communicating philanthropy: The media and the voluntary sector in Britain. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 6(2), 119–139.

Deegan, C., Rankin, M., & Tobin, J. (2002). An examination of the corporate social and environmental disclosures of BHP from 1983–1997: A test of legitimacy theory. Accounting, Auditing, and Accountability Journal, 15(3), 312–343.

Deephouse, D. (1996). Does isomorphism legitimate? Academy of Management Journal, 39, 1024–1039.

Deephouse, D., & Carter, S. (2005). An examination of differences between organizational legitimacy and organizational reputation. Journal of Management Studies, 42(2), 329–360.

Deephouse, D., & Suchman, M. (2008). Legitimacy in organizational institutionalism. In R. Greenwood, C. Oliver, K. Sahlin, & R. Anderson (Eds.), The Sage handbook of organizational institutionalism (pp. 49–77). London: Sage.

Doh, J. P., & Guay, T. R. (2006). Corporate social responsibility, public policy and NGO activism in Europe and the United States: An institutional-stakeholder perspective. Journal of Management Studies, 43(1), 47–73.

Doh, J. P., & Teegen, H. (2002). Nongovernmental organizations as institutional actors in international business: Theory and implications. International Business Review, 11, 665–684.

Dowling, J., & Pfeffer, J. (1975). Organizational legitimacy: Social values and organizational behavior. The Pacific Sociological Review, 18(1), 122–136.

Durrani, A. (2011, 19 April). MailOnline overtakes Huffington Post to Become World’s No. 2. Retrieved from http://www.mediaweek.co.uk/News/MostEmailed/1066247/MailOnlineovertakes-Huffington-Post-become-worlds-no-2/

Entman, R. M. (1993). Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. Journal of Communication, 43, 51–58.

Field, A. (2009). Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics (3rd ed.). Los Angeles: Sage.

Fiol, C. M., & Romanelli, E. (2012). Before identity: The emergence of new organizational forms. Organization Science, 23(3), 597–611.

Fleiss, J. L., Levin, B., & Paik, M. C. (2003). Statistical methods for rates and proportions (3rd ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley.

Florini, A. (2008). International NGOs. In S. Binder, R. Rhodes & B. Rockman (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of political institutions (pp. 1–27). doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199548460.003.0034

Gamson, W. A., & Modigliani, A. (1989). Media discourse and public opinion on nuclear power: A constructionist approach. American Journal of Sociology, 95(1), 1–37.

Ganesh, S. (2003). Organizational narcissism: Technology, legitimacy, and identity in an Indian NGO. Management Communication Quarterly, 16, 558–594.

Gibbert, M., & Ruigrok, W. (2010). The “what” and “how” of case study rigor: Three strategies based on public work. Organizational Research Methods, 13(4), 710–737.

Giles, D., & Shaw, R. L. (2009). The psychology of news influence and the development of media framing analysis. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 3(4), 375–393.

Glynn, M. A., & Abzug, R. (2002). Institutionalizing identity: Symbolic isomorphism and organizational names. Academy of Management Journal, 45(1), 267–280.