Abstract

Housing is an area in which the active involvement of citizens in the provision of services has the potential to enrich individual lifestyles, local communities and the organisations providing housing, regardless of whether public, private for-profit or non-profit. Yet in current housing markets, housing tends to be purely individual, in the form of home ownership, or collectively managed through social rented housing. The article explores the conditions under which co-production in this field could be successful, as an alternative model. The analysis, which draws upon the work of Ostrom, is based on empirical fieldwork carried out among German housing cooperatives. As it turns out, successful co-production depends primarily on the long-term maintenance of group boundaries and specific trajectories of organisational development. This can make co-production an attractive model for specific social groups, but there are drawbacks: it also tends to lead to limited use of the invested capital and an inward orientation.

Résumé

Logement est une zone dans laquelle la participation active des citoyens dans la prestation de services a le potentiel d’enrichir les modes de vie individuels, collectivités locales et les organismes de fourniture de logements, peu importe si le public, privé à but lucratif ou à but non lucratif. Encore dans les marchés du logement, logement tend à être purement individuelle, sous la forme d’accession à la propriété ou gérés collectivement par l’entremise de logement locatif social. Cet article explore les conditions en vertu de laquelle coproduction dans ce domaine pourrait être couronnée de succès, comme un modèle alternatif. L’analyse, qui s’inspire des travaux de Ostrom, repose sur empirique sur le terrain réalisé auprès de coopératives de logement allemand. Il s’avère que, coproduction réussie repose principalement sur le maintien à long terme de limites de groupe et des trajectoires de développement organisationnel. Ceci peut rendre le co-produit un modèle attrayant pour des groupes sociaux spécifiques, mais il existe des inconvénients : elle a aussi tendance à mener à l’utilisation limitée du capital investi et une orientation vers l’intérieur.

Zusammenfassung

Gehäuse ist ein Bereich, in dem die aktive Beteiligung der Bürger an der Erbringung von Dienstleistungen das Potenzial hat, individuelle Lebensstile, Gemeinden und Organisationen Gehäuse, unabhängig davon, ob die öffentlichen, privaten Profit oder Non-Profit zu bereichern. Noch tendenziell in aktuellen Wohnungsmärkte, Gehäuse rein individuell, in Form von Wohneigentum oder durch soziale Mietwohnungen gemeinsam verwalteten. Der Artikel untersucht die Bedingungen unter denen Koproduktion in diesem Bereich erfolgreich, als ein alternatives Modell sein könnte. Die Analyse, die auf den Arbeiten von Ostrom zieht, basiert auf empirischen Feldforschung bei deutschen Wohnungsbau Genossenschaften durchgeführt. Wie sich herausstellt, hängt erfolgreiche Co-Produktion vor allem die langfristige Erhaltung der Grenzen und bestimmte Bahnen der Organisationsentwicklung. Diese kann Koproduktion ein attraktives Modell für bestimmte soziale Gruppen machen, aber es gibt Nachteile: es neigt auch zu begrenzten Verwendung des eingesetzten Kapitals und eine innere Orientierung führen.

Resumen

La vivienda es un área en la cual la participación activa de los ciudadanos en la prestación de servicios tiene el potencial para enriquecer los estilos de vida individuales, las comunidades locales y las organizaciones proporcionar alojamiento, independientemente de si es público, privado con fines de lucro o sin fines de lucro. Aún en los actuales mercados de la vivienda, vivienda tiende a ser puramente individual, en forma de propiedad de la vivienda, o colectivamente gestionada a través de viviendas sociales de alquiler. El artículo explora las condiciones bajo las cual coproducción en este campo podrían tener éxito, como un modelo alternativo. El análisis, que se basa en el trabajo de Ostrom, se basa en campo empírica llevada a cabo entre las cooperativas de vivienda alemán. Como resulta, coproducción exitoso depende principalmente en el mantenimiento a largo plazo de las fronteras del grupo y trayectorias específicas de desarrollo organizacional. Esto puede hacer coproducción un modelo atractivo para determinados grupos sociales, pero hay desventajas: también tiende a conducir a un uso limitado de capital invertido y una orientación hacia adentro.

摘要

房屋问题是这一领域,提供的服务在公民的积极参与丰富个人的生活方式、 当地社区和提供住房,无论是否公共组织、 私人营利性或非营利性组织的潜力。然而在当前住房市场,房屋往往是纯粹是个人的自置居所的形式或通过社会租住房屋集体管理。这篇文章探讨了条件下在这一领域的联产可能是成功的作为一种替代的模型。分析、 绘制奥斯特罗姆的工作,基于实证的田野调查德国住房合作社之间进行。事实证明,成功联产主要取决的长期维护的组边界和特定的组织发展的轨迹。这可以使联产吸引力模型为特定的社会群体,但也有缺点: 它往往还会导致使用有限的投资的资本和外来的方向。

ملخص

الإسكان هو مجال فيه المشاركة الفعالة للمواطنين في تقديم الخدمات لديه القدرة على إثراء أنماط الحياة الفردية، والمجتمعات المحلية والمنظمات توفير السكن، بغض النظر عن ما إذا كان الجمهور الخاصة التي تستهدف الربح أو غير هادفة للربح. حتى الآن في أسواق الإسكان الحالية، الإسكان تميل إلى أن تكون فردية بحتة، في شكل ملكية المنزل، أو تدار جماعياً من خلال المساكن المستأجرة. المقالة يستكشف الشروط تحت أي الإنتاج المشترك في هذا الميدان يمكن أن تكون ناجحة، كنموذج بديل. التحليل الذي يستند إلى عمل اوستروم، يستند إلى العمل الميداني التجريبية التي أجريت بين التعاونيات السكنية الألمانية. كما اتضح، الإنتاج المشترك الناجح يعتمد أساسا على الصيانة الطويلة الأجل لحدود المجموعة ومسارات محددة للتطوير التنظيمي. هذا يمكن أن يجعل الإنتاج المشترك نموذجا جذاباً لفئات اجتماعية محددة، ولكن هناك عيوب: أنه يميل أيضا تؤدي إلى الاستخدام المحدود لرأس المال المستثمر وتوجه إلى الداخل.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In recent years, it has often been argued that self-organisation and active citizenship need to be encouraged (Verschuere et al. 2012). This also applies to the field of housing. Few would deny that it would be desirable for more citizens to become more actively involved in their living environment. That much is clear. What is less obvious is what can specifically be done to encourage this involvement.Footnote 1

Many of today’s private social landlords were originally born out of initiatives undertaken by citizens and communities who wanted to create an alternative to the existing supply on the housing market. Yet civic involvement in housing has tended to decrease over time. Bureaucratisation, mergers and up-scaling have meant that existing suppliers of housing have become estranged from the communities which they were once active in or, in the case of private non-profit organisations, which they were once linked to. When these suppliers are positioned somewhere between the state, the market and civil society (Brandsen and Karré 2012), they have tended to move towards either the state or the market: civil society seems to be a weak point. The question is whether they can re-strengthen this link with civil society.

In order to answer this question, we have searched for other forms of organisation in the field of housing, which might be better placed to mobilise the civic potential of their residents. We have carried out research among small-scale cooperatives in Germany, which in terms of their social dynamics come close to what we would understand as co-production. These cooperatives are so widespread that they cannot simply be dismissed as a marginal phenomenon. They thus constitute a ‘critical case’ which could shed light on the circumstances under which co-production could be made to work in the field of housing.

First, we will set out our theoretical foundation and methodological choices. We will then focus on the specific functions of housing as a capital good, a consumer good and a form of social investment. We will then describe our empirical investigation of German housing cooperatives. This will lead us to the formulation of some conditions that need to be met in order for successful co-production in this area to be able to occur. Inevitably, this leads to the ambition to achieve effective co-production within small communities and the desire for an effective use of capital and other resources for the broader environment beyond those communities. We end the article with a suggestion for how to resolve the tension.

The Interaction Between Individual Motivation and Collective Action

Individual Motivation and Collective Action

To analyse co-production properly, we first need a clear picture of the motivations of the citizens involved. Co-production in the field of housing must begin with communities of individuals with a shared goal. How does this shared goal come about, and how does it stand the test of time? This will be the starting point of our analysis.

We will begin our exploration with a quotation from former British Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher: “There is no such thing as society. There are only individual men and women” (Thatcher 1987). From this perspective on society, the individual assumes the most important place, and what is more, it is assumed that an individual acts solely and exclusively out of self-interest. Any collective interest that people may share is, from this perspective, simply the sum of their individual interests. Under Thatcher’s individualistic approach, it is difficult to understand and explain collective action. In reality, we can observe that people are certainly capable of organising themselves in such a way that they can accomplish goals that would remain unattainable if they all acted as individuals. We also know that people often act out of mixed motivations. In other words, we want to achieve something good for ourselves and for other people, and as long as we are confident that other people want the same and will behave accordingly, we are prepared to contribute to communal arrangements. In fact, collective arrangements that are based either on self-interest or on altruism exclusively are, in practice, the least sustainable (Le Grand 2003).

In this article, we will work on the basis that a contradiction between individual and collective interests is one possible scenario, but not the only possibility. It is of course possible that the interests of the individual and collective interest may not coincide—for example, when collective investment detracts from the quality of life of some residents and they oppose this investment. However, it is also possible for the interests of the individual and the collective interest to coincide, for example when an individual invests in communal property and by doing so enhances his own quality of life. The question then becomes—how can housing be organised in such a way that these two types of interest are made to coincide?

Previous research has shown that people need rules and structures for this. The question is which (types of) rules and structures will bring about an alignment of individual interests with collective interests? This has always been an important issue in social science and remains an extremely complicated question for today’s policymakers. Within social science, where the dilemma of collective action is essential, an exception is often made for small-scale, voluntary arrangements. The sociologist Mary Douglas put it this way: “Small-scale societies are different. Many who are well apprised of the difficulty of explaining collective action within the theory of rational choice are content to make exceptions. Smallness of scale gives scope to interpersonal effects. […] Consequently, there seems to be no theoretical problem about altruism when the social organization is very small” (Douglas 1986, p. 2). But what is it precisely that makes a small group or organisation less susceptible to the problems associated with collective action?

Such issues are at the heart of the work of Elinor Ostrom, who set out to discover the conditions under which individual interests and community interests can be aligned. More specifically, she researched the large variation in the ways in which common-pool resources become institutionalised and are managed (Ostrom 1990, 2005). Common-pool resources are associated with specific collective action problems that relate to the fact that the good involved is, by definition, semi-collective. As shared resources or supplies, common-pool resources are significant to all those entitled to use them, but individual members may end up using so much of the resource that other members (or potential future members—and thus future generations too) may be left without enough. Housing can be conceived of as a common-pool resource (Helderman 2007). More specifically, it can be seen as a form of insurance against future investment risks in the field of housing. A dwelling, for example, can serve as collateral for new investment and at a collective level, the entire housing stock and the capital that is tied up in it can serve as a similar source of funding for future investments (Kemeny 1995).

Elinor Ostrom’s research focused specifically on the question of under what institutional conditions common-pool resources can be managed in a sustainable way. Her research concerned communal water resources, but what she discovered about the conditions that lead to successfully managed communal water resources can easily be transferred to the management of housing stock. On the basis of empirical research, she reached the following design principles for the successful management of common-pool resources (Ostrom 1990, p. 90).

-

The boundaries of the common-pool resource itself and the group of users must be clearly defined.

-

Rules concerning use and provisions (such as the division of living space or investment) must be adapted to local circumstances.

-

Using collective choice mechanisms, the actors involved in the collective housing stock must be given the opportunity to participate in decision making in some way—whether directly or through representation.

-

Monitoring must be carried out in a way that is transparent and accountable to the actors involved.

-

Sanctions for violations of the rules must be graduated according to the seriousness of the violation.

-

Social infrastructure must be put in place for the resolution of any conflicts that arise between the actors involved.

-

The right of the community to organise itself must not be undermined by external authorities.

-

When the common-pool resource is part of a larger system (such as the social housing stock), activities involving the removal of resources from the system, provision, monitoring and other relevant forms of management, must be organised close to the local level.

In this article, we will demonstrate that several of these conditions apply to our case study of co-production in housing. By implication, co-production in this field can only succeed where certain social limitations are accepted and constantly maintained.

Methodological Considerations

The German housing cooperatives were chosen for two reasons. Research had already indicated that a number of the Wohnungsgenossenschaften had succeeded in getting their residents to play a more active role in and around their immediate living environment and that lively communities had formed around these organisations. That made them an interesting case study through which to look at co-production. Furthermore, the German cooperative housing sector houses a broad cross-section of the population, and includes both recently established and much older organisations. This enabled us to form a varied picture of the various phenomena in the sector and the development of co-production.

In Germany, housing cooperatives account for around 10 % of the housing market. As such, Germany is one of Europe’s frontrunners when it comes to cooperative housing (Harloe 1995). In the German housing market, housing bears a closer resemblance to a consumer good than in Anglo-Saxon markets, where its function as a capital good is more dominant (Muellbauer 1998; Helderman 2007). This has been confirmed by research on household perceptions (Elsinga et al. 2007). In Germany, owning one’s own home is perceived principally as a form of investment in one’s future security. Any rise in the value of housing is assessed in terms of its effect on securing one’s future housing needs, rather than in terms of property. Tenants and home owners also share a very similar perception of the economic value of their home in Germany (Tegeder and Helbrecht 2007). In Anglo-Saxon countries, on the other hand, property markets are unstable and subject to large price fluctuations, and tenants and home owners have a quite different perception of their own homes. In fact, this observation reveals the first important characteristic which can enable co-production in housing in the form of housing cooperatives. The way in which the housing market is institutionalised and the economic dynamic associated with it is a significant factor. Housing cooperatives are better able to flourish in a stable housing market where the economic purpose of housing is perceived principally in terms of its practical use.

Some years ago, large-scale quantitative research was carried out into the Wohnungsgenossenschaften, which meant that some basic data concerning the scale and institutional form(s) of this type of organisation in the German housing market were already available (Expertenkommission Wohnungsgenossenschaften 2004). This enabled us to concentrate our efforts on intensive research at the organisational level. Some basic questions about structures and procedures were answered using documentation analysis. In addition to that we carried out intensive case study research. This was based on interviews with the board members, residents and municipal officials in and around seven mainly smaller organisations. The Wohnungsgenossenschaften we worked with were located in the cities of Berlin, Hamburg and Munich, which enabled us to research the role of the cooperatives in various types of local property markets.

The research was financed by Futura, a network of non-profit (social) housing corporations in the Netherlands. The research objectives were arrived at in consultation, but the authors of this article determined the research methods themselves. Of course, given the scale of the research, it can only be seen as exploratory in nature. Nevertheless, it does go some way to revealing the factors which are behind successful co-production. Some of these factors are specific to the field of housing and for that reason it is now necessary to take a closer look at this specific field.

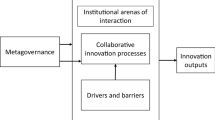

The Functions of Housing

The conditions necessary for co-production are closely linked to the functions of the product or service in question and with the consequences of co-production in a specific sector or field (Brandsen and Pestoff 2006). We will here analyse the field of housing on the basis of its three functions: its capital function, consumer function and social investment function (Brandsen and Helderman 2012). Each of these can have an impact at various levels: at the level of the individual resident, or at higher, collective levels such as that of the community which the resident belongs to, or of the city as a whole.

The considerable investment required and the fact that this is often extended over the long term means that housing has a function as a capital good. Most of the finance is needed ‘up-front’ to make the purchase itself. Loans are often used to raise this finance, sometimes in the form of a personal loan (a mortgage) or through the capital market. An important choice is the extent to which profits or losses from sale of the dwelling are passed on. When the dwelling is the property of an individual home owner, the resident shares directly in the increase (or decrease) in its value. When a property is owned collectively, the range of possibilities is greater. If the sum paid by the individual for using the property is independent of any changes in the value of the property, capital profits can also be used to maintain the collective property and make new investments. At the collective level, the capital function can thus be translated into an arrangement that provides maximum security of tenure. Traditional German housing cooperatives, for example, expressly emphasise this type of security, which is passed on to the residents at an individual level.

In addition to the capital function, housing has a consumer function. Simply, people need a roof over their heads. However, housing can also fulfil several consumer functions simultaneously. When residents live together in a shared residential environment, they can also help and support each other in various aspects of their lifestyles. Parents can babysit for each other’s children, and people with handicaps can give each other a helping hand. Individual interests are thus served by the community, enhancing the consumer function of housing.

Finally, housing has a social investment function. Housing provides the opportunity to realise social ideals such as empowerment. The housing market has always been closely associated with socio-economic status and social mobility. Ecological sustainability is also becoming ever more prominent nowadays as an ideal to be put into practice. All this means that housing suppliers can take on a social enterprise role. Landlords may for example choose to focus on individual social advancement or invest to enhance the environmental sustainability of their dwellings.

Evaluations of co-production in housing are most often framed in terms of the consumer function, but the effect of co-production on the other functions of housing must also be taken into consideration, otherwise we will only see one side of the story, in which only the advantages of this form will be emphasised. As we will see in the following sections, co-production in housing can also have disadvantages.

Small German Housing Cooperatives: Et in Arcadia Ego?

This section shows how co-production is present in the organisations we studied and the circumstances that lay behind this.

The Good Life

The cooperatives that we researched often had something of the utopian idyll about them. On some occasions that was clear as soon as we arrived. The first cooperative that we visited had traditional red brick courtyards with benches, flowers and balconies looking out. There were a couple of children’s bicycles lying on the ground. Elsewhere, we visited colourfully painted rows of family houses, each with a long strip of garden out back, tended attentively by the residents. As we walked past, many of the residents were out clipping their hedges. In another location, we visited an area of architecturally surprising modern housing with an abundance of wide open green spaces and attractive communal areas. Of course, not all the buildings owned by the cooperatives were as striking as these, but many organisations prioritised architectural quality, and this was also a source of pride. Many of them view the design and maintenance of the buildings they own simply as part of their social responsibility.

There is a relatively low turnover among tenants. Germany is characterised by a relatively high proportion of vacant housing, particularly in Eastern Germany, but this is significantly lower among housing cooperatives than in other types of housing providers. In the majority of residents of newer cooperatives, the residents are still those who originally established them. The mix of residents in the traditional Genossenschaften is fairly varied, but they are particularly popular among certain groups. These are mainly households who can help each other directly—the elderly, families with children, the handicapped. In addition, some managers pointed out growing interest among single people over the age of 40, particularly women. In fact, many of the managers were themselves middle-aged women—a group that has traditionally played a significant role in voluntary work. The cooperatives are particularly attractive to one- and two-person households with a certain lifestyle—often these are people who could actually live independently but who have much to gain from life in an integrated community. But where cooperatives have already been established for a long time, the preference of the residents for living in a certain neighbourhood can also be decisive.

Managers pride themselves in their active residents. This usually involves some kind of self-help. Particularly in smaller communities, mention was made of mutual assistance such as doing shopping for one another or babysitting for each other’s children. In addition, during our interviews with many traditional housing cooperatives, they referred to a wide range of organised activities—the elderly go on coach trips together, as far afield as the Arctic Circle; games and treasure hunts are organised for children; those who love walking set off to the woods together. Every cooperative has a yearly winter street-party with mulled wine, and countless cups of tea and coffee are enjoyed together.

Yet the larger Genossenschaften experienced familiar problems. All these activities tended to depend on a hard core of mainly older residents. Many of the members acted just like tenants of regular social housing, doing nothing more than paying their monthly rent. Some cooperatives had begun experimenting with other forms of participation such as funds to be spent by residents for which residents could submit their own ideas. But here, too, falling levels of participation were a cause of concern. Nevertheless, the long average tenure of residents and the small-scale of the organisations (achieved by, for example, transferring the democratic decision-making structure to the level of individual housing complexes) contribute to a relatively high level of active involvement. What is more, most small cooperatives seem to be able to involve their members even more intensively—°members typically participate in management and forms of direct democracy which are anchored in their organisational structure.

Born Out of Social Movements

There is a significant amount of variation among German housing cooperatives. The clearest difference is between the older Genossenschaften and those that have been instituted more recently. Many of the older cooperatives were founded in the second half of the nineteenth century and vary greatly in size from a few thousand residents to tens of thousands of dwellings, although they are smaller on average than the municipal housing organisations. The newer cooperatives are significantly smaller, with sometimes only a few hundred dwellings.

The older cooperatives have a history similar to that of non-profit housing corporations in the Netherlands. During the industrial revolution, there was a massive movement of workers to the urban centres, where they could not all be housed. Families were squeezed together into tiny dwellings where living conditions were often squalid. This was at its most severe in Berlin, where they joked: ‘There’s a basement flat above us that’s going to be vacant soon’. Benevolent groups of idealists, often with connections to the workers movement, founded new colonies around the edges of town where they sought to promote community spirit and mutual assistance, and provide housing with more light and air. Even today, many of the cooperatives still have close political links to the Social Democratic Party (SPD). Later, many of the Genossenschaften helped in the post-war reconstruction of the cities which had been bombed. They were given state grants to build social housing. But these grants come with strings attached: if a dwelling was built with the aid of construction subsidies, the municipality was then entitled to house whoever it wanted there—and these were not always neighbours of the sort that the existing residents would look favourably on.

The newer Genossenschaften have their origins in more recent social movements. For example, in cities such as Hamburg, collective forms of housing were a means of tackling the issue of squats in the city. Following German reunification, there was a new wave of Genossenschaften, supported by favourable local subsidy schemes and spurred on by worries about housing being sold off to private property speculators (the ‘cherry-pickers’). During the 1990s in Dresden, for example, the municipality sold 47,000 dwellings from its stock of social housing to foreign investment companies. Particularly in the eastern part of the new Germany, residents took matters into their own hands and bought up existing housing estates or plots of land. This type of initiative and the associated financial risks were linked to a desire for security of tenure and self-determination, and for a home that would never have to be sold again and where the only risks residents had to take were risks they chose to take themselves. A number of new initiatives had links with the ecological ‘green’ movement and in these; sustainable buildings were given a high priority.

In smaller organisation, the highest administrative organ is the general meeting of members. In larger Genossenschaften, members are represented indirectly. Management duties are carried out by two or three members—in smaller cooperatives they may work on a partly voluntary basis. The management has a supervisory board which is consulted regularly and whose members have the power to dismiss the management if necessary. The administrative structure consists mainly of technical staff and caretakers. This democratic structure is fixed and replicated on a smaller scale within individual housing complexes.

History has left its mark very clearly on the Genossenschaften, which have been shaped by social transformations. The older cooperatives were a response to rapid urbanisation during the industrial revolution of the nineteenth century. The more recently formed cooperatives were formed during the turbulent period that followed German reunification and the globalisation of capital markets at the end of the twentieth century. Few new Genossenschaften are being formed today because both public and private forms of funding are less freely available. But it is possible that the demographic turning point that is due to take place around the middle of the twenty-first century may result in a new wave of Genossenschaften for two reasons. First, in a shrinking housing market, the Genossenschaften will face lesser competition from for-profit investors in the land market, the capital market and the housing market. Second, the Genossenschaften seem to be particularly well suited to combine the provision of housing services with the provision of care services for the elderly. Hence, with an ageing population, the potential demand for sheltered housing in cooperatives may rise.

Financial Background

In the field of housing, unlike in many other forms of service provision, it is possible to function for long periods without the financial support of government or other financial backing. Capital invested in housing generates its own income through rents or the proceeds of sales. A very large investment is required ‘up-front’, however, and support from external financiers is nearly always necessary for this.

The Genossenschaften vary in the degree to which they have received financial support, but only a few have managed without any form of subsidy at all (when implicit subsidies are included). After all, they cater for a stratum of the population which is not the lowest in economic terms (or they would not be able have any capital to contribute) but not particularly rich either (or they would probably choose to own their own home). There is also very little room for manoeuvre: the cooperatives promise their residents absolute security and any sale of the properties is virtually out of the question. The scope for rent increases is also limited, both in legal terms and by the financial position of the tenants. The legal support measures from which the cooperatives used to benefit were abolished during the first decade of this century. Direct subsidies do still exist, and come mainly from the regional (Länder) or municipal levels of government. But even so, the cooperatives are forced to keep an eye on every penny. Larger cooperatives are often financially stable, but the smaller ones are engaged in a constant struggle for survival. In a few cases known to us, established cooperatives have lent their support to new cooperatives during the start-up phase by providing advice, but there is no question of any financial support between cooperatives. Not only are there limited resources available to share, but cooperatives tend to focus on their own community and their own immediate environment; this is both their strength and their weakness.

The main way in which cooperatives receive external financial support is through favourable terms of credit. The largest risks are during the set-up phase. Many new initiatives have had to be abandoned during this phase. Groups of residents who wanted to set up cooperatives have had to rely almost entirely on state banks or banks motivated by other ideals than purely profit alone. Regular banks have remained reluctant to help and have only really shown interest once the risky phase is over. A few years ago, bank managers invited a housing cooperative customer to visit them and politely explained that the cooperative was no longer an attractive customer for the bank, with only a few millions in credit (a further ironic twist in this story: on the day of our interview with this cooperative in 2009, the very same bank was about to collapse due to taking on subprime mortgage debts from the United States).

In the past, some cities have also supported alternative forms of housing directly, albeit sometimes on a temporary basis. For example, the municipality of Berlin extended grants for set-up and renovation costs, which were later scrapped when the city ran into financial problems. However, this did provide a window of opportunity that enabled a number of cooperatives to get established. These kinds of arrangements existed throughout Germany, although they have by no means always been successful. Hamburg is an interesting case: the city government began to encourage housing communities there in the 1980s. A proportion of land in the city—which is in short supply and thus expensive—is set aside for collective housing and a subsidised foundation supports residents who want to prepare applications and get established. It is interesting to note that the traditional cooperatives also began by setting up housing communities because it was one of the few ways of being able to acquire land.

In short, cooperatives have to get established in a difficult and sometimes fickle environment, where the support they require cannot always be found. Those cooperatives that survive are only able to achieve some degree of stability over time. So it seems that even this form of self-organisation requires a push to get it started. But just how strong does that push need to be? As we shall discover, the answer to that question involves finance, but has social aspects too.

At first glance, decision-making structures play an important role in this. Cooperatives that have been set up more recently usually incorporate some form of direct democracy or associational democracy through which members can be involved in decisions on strategy and management. Older, larger cooperatives are usually run on the basis of indirect representation. Their identity is influenced to a significant extent by their democratic structure. Even in the traditional cooperatives, members have the power to dismiss those that run them. However, the cooperatives we researched did not differ radically from the housing corporations of the Netherlands. The decision-making procedures were reminiscent of the original housing associations and many of the initiatives at the level of individual housing complexes have equivalent forms in the Netherlands.

More important than the formal structure are the informal ties between residents. A number of cooperatives succeed in aligning their residents’ interests as individuals and the interests of the community as a whole. The most important factor in this is how residents’ involvement is built up over time. The smaller, newer cooperatives are without exception based on communities which were already in the process of being formed before the housing cooperative itself was established. Sometimes these communities are strengthened further by some form of participation in the physical construction process itself. To a certain extent, social bonds also have an important role to play in the more traditional cooperatives. They often have a loyal core of resident families who, over the generations, have long made up part of the community as a result of allocation mechanisms. In both cases, the housing communities are based on established social and/or family ties.

Communities cannot be created, but they can evolve and thereafter can be maintained. As our description has shown, housing cooperatives in Germany are characterised by a combination of closed membership and community interests. The original community is carefully protected by laying down clear boundaries for what can be changed—both in terms of the residents and financial and economic conditions. Members of the smaller cooperatives in particular have a clear interest in preserving their own communities—and the survival of the community depends on closed membership.

Controlling the Boundaries of the Community

We do not wish to give a distorted picture of the German Genossenschaften: not all of them excel in building an active sense of community. Even in the housing cooperatives of Germany, only a limited number of organisations have residents who are highly active. But why do some organisations manage it, while others do not?

It is true that residents stay in their homes longer, that there are close relations between managers and residents, and that there was a relatively large amount of contact between residents. Certainly in the smaller organisations, residents are closely involved in management. This means of management is also essential to smaller organisations as a means of cost reduction—they are kept running through voluntary work and low turnover.

The German cooperatives exhibit all the classic hallmarks of strong communities: membership is—to some degree—closed, they are kept deliberately small in scale and there is a clear community interest. Herein lies both the strength and the weakness of housing cooperatives. This is a model from which there is much to learn, but also one that comes with a price tag attached.

To start with, it should be emphasised that the communities have not come into existence through the cooperatives, but rather the cooperatives have been built around existing groups. New organisations were set up by groups of enterprising individuals, who then went on to enlist more residents. These groups put a great emphasis on relations between residents before the first brick was laid. In one of the cases we researched, the future residents of the cooperative were obliged to help finish off the buildings in the final phase of construction so that they would get to know each other properly. The cooperative is thus an instrument rather than an end in itself. More importantly still, perhaps, the cooperative is the instrument of a specific group which has its own goals.

What also plays an important role here is that cooperatives have remained relatively small in scale. There are a few large cooperatives with over 10,000 homes, but two-thirds of all cooperatives own <20 % of the total stock of cooperative housing, with the average cooperative extending to a total of 1,200 homes. The Wohnungsgenossenschaften generally have a strategy of limited expansion, and sometimes limit themselves simply to renovation and maintenance. This means that the number of homes that become vacant is consistently low.

This leads us logically to the question of how accessible the cooperative in fact are. On this point, the cooperatives we researched provided some very contradictory evidence. They invest a great deal in the transparency of their housing distribution methods. Allocation decisions are usually published and explained. Sometimes residents receive a personal letter to explain why they have not been allocated a specific dwelling. In principle, anyone is free to apply for housing. The sum required—between €500 and €1,000—is by no means excessive. Some cooperatives offer a savings variant, which involves acting as a kind of bank for members as a means of raising extra capital from them. There are no limits on income.

On paper, then, the cooperatives could hardly seem more welcoming. But in practice, the situation is rather more complex. As mentioned, in reality very few homes actually become vacant. In addition, those that do become vacant are generally taken rather quickly. In principle, anyone who is prepared to accept the obligatory share purchase can apply for the dwelling. In reality, though, many family homes stay in the hands of the same families. It is common practice for children who are born within the cooperative to be registered as members immediately and to receive shares as gifts from their parents or godparents. Thirty years later, they will have been registered for long enough to be entitled to a family home. This intergenerational transfer of homes means that cooperatives often retain an intergenerational core of residents who are closely involved. All of this is perfectly within the rules of registration, but the length of registration is so long that outsiders hardly ever get the chance to move into the most sought after family houses. The only way into some Genosssenschaften is by being born into them or by first occupying a single-person’s home. Those who want to move up to a larger home are then put on a very long internal waiting list.

Conflict-Avoiding Behaviour

The low turnover in tenants of housing cooperatives is linked to the priority that they accord to ownership rights. This means that there are seldom grounds for any conflict. Increases in property values hardly exert any influence at all in the cooperatives which we studied. Each member is obliged to invest a certain amount in shares in the cooperative—a relatively low sum for traditional cooperatives, but substantially more in new cooperatives. In return they receive an annual dividend, usually a fixed percentage of between 2 and 4 %. As a financing mechanism, this is similar to a deposit savings account with a bank (since the credit crisis, we perhaps ought to clarify this further: the type of bank account where you are guaranteed your original deposit back). The difference is that members of German housing cooperatives seldom leave and thus seldom have their original deposit returned. In the event of a member leaving, he or she will only be given their deposit back. It is a sober system which minimises conflicts concerning financial distribution and makes profit-seeking strategies impossible.

In this way, the principle of security of tenure is translated towards every level. This security is very much a key principle for cooperatives and it also leads to a scrupulous investment policy. Any expansion of cooperatives is usually limited—sometimes a small housing complex will be added. A conscious effort is made to strike a balance between economies of scale and retaining the small scale of the cooperative. This means that hardly any cross-subsidisation takes place—in principle, each housing complex needs to be financially self-sufficient. This also contributes to the conciliatory nature of relationships within the cooperatives—existing organisations can gain from economies of scale through expansion, but do not need to invest to do this.

Finally, the internal structure of cooperatives, particularly smaller ones, ensures that residents are well informed about any developments. Communication plays an essential role in organisations of all sizes—they organise meetings, hold open days, write letters and employ wardens. This does not mean that managers and members are of equal rank, however. The difference in the levels of knowledge between the two groups is enormous even under this form of housing ownership, and it cannot be denied that some managers act paternalistically. But the bottom line is that residents are secure in their homes and ultimately they have the power to dismiss managers. This too gives residents a feeling being able to decide their own destiny.

A Limited Focus

Even the most dynamic Genossenschaften have a view which is restricted only to their own neighbourhood—they are very active within their own ‘territory’ but no further. There is also criticism on the part of local authorities. “Our experience is that there is little willingness to feel responsible. If there was coordination between them, that would be different, but often they don’t even know what their immediate neighbour is doing”. The cooperatives look inwardly, first of all, and have neither the financial capacity nor the personnel to take on a broader role. Certainly, the cooperatives are islands of stability with a favourable influence on their immediate environment. Their residents are relatively closely involved in managing their housing complexes and the streets around them. They attract volunteers, are attentive and reliable, and maintain their properties well—the perfect neighbours, one might say. But when it comes to broader concerns like urban renewal, it is the project developers and the municipal housing authorities that call the shots, not the Genossenschaft. Although the Genossenschaften have their local federations, it should be emphasised that these federative organisations and the individual cooperatives are more oriented towards satisfying the housing needs and demands of their members than towards contributing to local and regional housing issues.

Conclusion: The Conditions Required for Co-production

Our research has focused on the question under what conditions co-production in housing can succeed, based on a study of German Wohnungsgenossenschaften (housing cooperatives). Almost all of the cooperatives resembled the ‘small-scale societies’ that Mary Douglas referred to, with high levels of volunteering and collective engagement. Interpersonal contact was important and was emphasised consistently by our respondents. While a certain degree of altruism probably played a role, what is more important is that in this type of small-scale community the shared interests of the cooperative were generally consistent with individual self-interests. This appears to confirm the general observation that institutional arrangements that appeal to mixed motives are the most sustainable (Le Grand 2003).

The conditions for successful co-production that we found match several of those that Ostrom (1990, 2005) previously identified for the successful management of common-pool resources. Specifically:

-

The boundaries of the cooperatives and the eligibility criteria that potential members needed to satisfy were well defined;

-

Rules concerning the use of the provision, including the withdrawal of housing services and decisions concerning new investments, were adapted to local circumstances;

-

The cooperatives had simple collective choice mechanisms and decision rules, often based on direct democracy; monitoring of the management board was directly accessible by the members of the Genossenschaften and the general meeting usually also served as an effective social infrastructure for the resolution of potential conflicts;

-

They were explicitly based on the right of communities to organise themselves. The Genossenschaften—once they got off the ground—were capable of surviving in the long term. Managing their existing housing stock sustainably was seen as being more important than making risky investments to attract potential new members or groups.

-

The Genossenschaften seldom disposed of the financial means to initiate risky new investments, and their internal decision-making structures had an intrinsically conservative effect.

In almost all cases, the cooperatives have chosen to pursue a cautious investment policy. They focus almost exclusively on the physical maintenance of the housing and on promoting social involvement among residents—they ignore considerations such as service provision, freedom of choice and profit making. This means that their model is by no means attractive for everyone. Indeed, some tenants regard it as positively restrictive. For others, the cooperatives are the ideal form of housing organisation. Our data suggested that the model appealed specifically to certain social groups (e.g. families with young children, the elderly, single middle-aged women). Within the communities, the German housing cooperatives we studied were extremely good at mobilising residents for collective action.

Yet there were also limitations and short-comings. To begin with, the cooperatives made limited use of their capital. As indicated, the cooperatives emphasised security of tenure above all else, which meant that they avoided making any risky investments. There was very limited cross-subsidisation, or none at all: each community was expected to provide for itself. The emphasis on security of tenure also meant that the sale of properties was often virtually impossible. On the one hand, that strategy leads to a high level of stability and a relatively low level of conflicts between members; on the other hand, it is not the most productive strategy for activating the capital invested in the housing stock. A second drawback was the limited reach of community spirit. The common experience was that it usually went no further than the next block. There is no denying that within these boundaries, the German Genossenschaften were home to very pleasant communities with a high degree of social involvement, many volunteers and a positive influence on their immediate environment. Yet essentially they remained friendly versions of the ‘gated community’, in which the ‘in-group’ assumes a central position. Whether that makes the model attractive or not, and for whom, is a normative topic for further discussion.

In other words, co-production in housing comes at a price. The ideal housing organisation would be one that invests broadly across the whole city, where residents share in the return on capital investments and yet still have a thriving community, happy to tend the communal gardens and clear the litter with a cheerful song. But it is probably the stuff that dreams are made of. The conditions that optimise performance for fulfilling one function are not compatible with the optimisation of performance in terms of other functions. Enabling residents to share in the rise in the value of their property is almost impossible to reconcile with maintaining the closed communities that are needed to preserve social stability.

This brings us to the question whether it is at all possible to achieve a better balance between social efficiency and social equity (efficiency and equity across different communities), while at the same time benefitting from the more responsive intra-communitarian quality of the cooperatives towards the needs and demands of their residents or tenants. This may be possible by decoupling the different levels within one organisation from one another. It would be unrealistic to expect a community to form around a total housing stock of, for example, 5,000 dwellings. Equally unrealistic would be to expect an organisation with a stock of 100 dwellings to play a role in the development of the city as a whole. However, a provider with 5,000 dwellings could accommodate an organisation for a housing community of 100 dwellings. In Hamburg, for example, some large cooperatives have allowed smaller housing communities a place within their housing stock when those communities are housed within one building or within a clearly demarcated area. At a lower scale level, it may be possible for existing housing providers to provide the conditions necessary for communities to form and co-production to occur. If such an approach were to prove successful, existing housing providers could function as a roof over the heads of co-production initiatives at lower levels.

Perhaps this process could enable these organisations to realise the potential they have to bring about social innovation without having to relinquish their traditional position, which over the years they have worked so hard to attain.

Notes

For a more elaborate description of this case and specifically of its position within the field of housing, we refer to a text published in the recent edited volume on co-production (Brandsen and Helderman 2012).

References

Brandsen, T., & Helderman, J. K. (2012). The conditions for successful co-production in housing: A case study of German housing cooperatives. In V. Pestoff, T. Brandsen, & B. Verschuere (Eds.), New public governance, the third sector and co-production. London: Routledge.

Brandsen, T., & Karré, P. (2012). Hybrid organisations: No cause for concern? International Journal of Public Administration, 34, 827–836.

Brandsen, T., & Pestoff, V. (2006). Co-production, the third sector and the delivery of public services: An introduction. Public Management Review, 8, 493–501.

Douglas, M. (1986). How institutions think. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press.

Elsinga, M., de Decker, P., Teller, N., & Toussaint, J. (Eds.). (2007). Home ownership beyond asset and security. Amsterdam: IOS Press.

Expertenkommission Wohnungsgenossenschaften. (2004). Wohnungsgenossenschaften: Potenziale und Perspektiven. Bau-und Wohnungswesen: Bundesministerium für Verkehr.

Harloe, M. (1995). The people’s home: Social rented housing in Europe and America. Oxford: Blackwell.

Helderman, J. K. (2007). Bringing the market back in? Institutional complementarity and hierarchy in Dutch housing and health care. PhD dissertation, Erasmus University Rotterdam.

Kemeny, J. (1995). From public housing to the social market. Rental policy strategies in comparative perspective. London: Routledge.

Le Grand, J. (2003). Motivation, agency and public policy: Of knights and knaves, pawns and queens. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Muellbauer, J. (1998). Anglo-German differences in housing market fluctuations, the role of institutions and macroeconomic policy. Economic Modelling, 11, 238–249.

Ostrom, E. (1990). Governing the commons. The evolution of institutions for collective action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ostrom, E. (2005). Understanding institutional diversity. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Tegeder, G., & Helbrecht, I. (2007). Germany: Home ownership, a janus-faced advantage in time of welfare restructuring. In M. Elsinga, P. de Decker, N. Teller, & J. Toussaint (Eds.), Home ownership beyond asset and security. Amsterdam: IOS Press.

Thatcher, M. (1987). Aid, education and the year 2000. Interview by Douglas Keay with Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher. Women’s Own, October 31, 1987, 8–10.

Verschuere, B., Brandsen, T., & Pestoff, V. (2012). Co-production as a maturing concept. Voluntas, 23. doi:10.1007/s11266-012-9307-8

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Brandsen, T., Helderman, JK. The Trade-Off Between Capital and Community: The Conditions for Successful Co-production in Housing. Voluntas 23, 1139–1155 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-012-9310-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-012-9310-0