Abstract

Guinea fowl coronavirus (GfCoV), a recently characterized avian coronavirus, was identified from outbreaks of fulminating disease (peracute enteritis) in guinea fowl in France. The full-length genomic sequence was determined to better understand its genetic relationship with avian coronaviruses. The full-length coding genome sequence was 26,985 nucleotides long with 11 open reading frames and no hemagglutinin–esterase gene: a genome organization identical to that of turkey coronavirus [5′ untranslated region (UTR)—replicase (ORFs 1a, 1ab)—spike (S) protein—ORF3 (ORFs 3a, 3b)—small envelop (E or 3c) protein—membrane (M) protein—ORF5 (ORFs 4b, 4c, 5a, 5b)—nucleocapsid (N) protein (ORFs N and 6b)—3′ UTR]. This is the first complete genome sequence of a GfCoV and confirms that the new virus belongs to group gammacoronaviruses.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Coronaviruses (CoVs) are enveloped viruses with positive-sense, non-segmented RNA genomes of 25–32 kb. CoVs infect a wide range of hosts causing various degrees of morbidity and mortality. Group I CoVs (alphacoronaviruses) contain viruses that infect not only humans (HCoV-229E and HCoV-NL63) but also cats and dogs (with feline CoV and canine CoV, respectively), or pigs (with the porcine transmissible gastroenteritis virus, TGEV for example). Similarly, group II CoVs (betacoronaviruses) may infect humans (examples: HCoV-OC43, HCoV-HKU1, severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)-related CoVs or the recently emerged MERS-CoV), horses (with ECoV), or cattle (with BCoV). In contrast, group III CoVs (gammacoronaviruses) primarily infect birds: chickens, peafowl, and partridges harbour infectious bronchitis virus (IBV) while turkeys have turkey CoV (TCoV) and guinea fowl may be infected with guinea fowl CoV (GfCoV). Gammacoronavirus strains have however been isolated from a whale and a wild felid [1]. Group IV CoVs (deltacoronaviruses) have been detected in birds (with BuCoV, MuCoV, SpCoV, etc.), or pigs (with porcine deltacoronavirus) [2]. Interestingly CoVs of the groups I, II, and IV have been detected in Chiroptera (bats), thought to be the reservoir of CoVs [3, 4].

In the present study, we focused on a new member of the group III CoVs, GfCoV, and aimed at sequencing its full genome to better understand its molecular relationship with gammacoronaviruses.

Materials and methods

To determine the full genome of gammaCoV/guinea fowl/France/s/2011 (GfCoV/FR/2011), we first analysed the data generated on a MiSeq Illumina platform as previously described [5]. Briefly, pooled intestinal contents of experimentally infected guinea poults were clarified, ultracentrifuged, and treated with nucleases to concentrate encapsidated viral material. RNA was extracted, and a random RT-PCR was performed to generate unbiased PCR products of about 300 bp [5, 6]. The sequences generated that matched with avian CoVs sequences, as determined using GAAS software [7], were extracted for further analysis and visualized using integrative genomics viewer (IGV) with the closest blast hit as reference genome: TCoV MG10 (accession number: EU095850) [8]. Primers were designed based on the known sequence data to amplify missing genome fragments by PCR. Sanger sequencing was then performed with PCR primers. The full genome sequence was submitted to EMBL and was attributed the following accession number: [LN610099]. Sequence analysis was carried out using BioEdit version 7.0.8.0 [9], muscle for the alignment [10], and mega version 5.05 for the phylogeny [11].

Results and discussion

The gfCoV-generated sequences were assembled into one contiguous coding sequence of 26,985 nucleotides. The entire genome had a GC content of 38.3 %, identical to the turkey coronavirus (TCoV) MG10 genome [12]. GfCoV and TCoV genomes have the same organization: (i) a 5′ untranslated region (UTR), (ii) two large slightly overlapping ORFs coding for the replicase: 1a and 1ab, (iii) gene coding for the spike (S) protein, (iv) ORF3 (ORFs 3a, 3b), (v) gene coding for the small envelop (E or 3c) protein, (vi) gene coding for the membrane (M) protein, (vii) ORF5 (4b and 4c, 5a, 5b), (viii) genes coding for the nucleocapsid (N) protein (ORFs N and 6b), and (ix) 3′ UTR (Table 1). The multiprotein on single ORFs is generated by alternative translation. While the role of avian coronavirus (IBV) structural proteins is known: binding to RNA, nucleocapsid formation and role in cell-mediated immunity for N; virus budding site determination, role in virus particle assembly and in interferon-induction, interaction with viral nucleocapsid for M; association with viral envelop, role in virus particle assembly and putatively in apoptosis for E; binding to cellular receptors, induction of fusion between viral and cellular membranes, induction of neutralizing antibodies and role in cell-mediated immunity for S; little is known on the function of non-structural proteins. It has mainly been shown that they are not essential for virus replication in vitro but likely help the virus replicate in vivo [13, 14]. The proteins 3a, 3b, 4b, 5a, and N were of the same size. Sizes of other proteins varied, but within the range observed previously between different TCoV strains. Interestingly, GfCoV/FR/2011 harboured a shorter small envelop protein than its TCoV counterparts (Table 1). Further studies are warranted to understand the impact of avian CoVs protein sizes in the biology of the viruses.

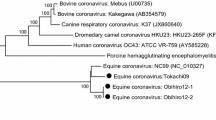

Phylogenetic analysis on the full genome of GfCoV/FR/2011 showed it clearly clustered with North American TCoV strains (Fig. 1a, supported by a high bootstrap value of 100), as it was observed previously for the S gene [5]. The genetic distance between GfCoV/FR/2011 and TCoV ranged between 10.7 and 11.4 %, while genetic distances between GfCoV/FR/2011 and representative IBV strains were larger and varied between 13.5 and 15.0 % (Supplementary Table). A simplot analysis comparing the GfCoV/FR/2011 full genome to its closest TCoV and IBV Blast hits showed that the three genomes are highly similar throughout the genome (74–100 % similarity, with no significantly higher identity of GfCoV/FR/2011 with TCoV or IBV genomes), except for the S gene (Fig. 1b). GfCoV S gene was indeed more closely related to TCoV S than to IBV S genes but also more distinct to both viruses on the S gene than on the rest of its genome (<50 % identity for IBV and 65–90 % identity with TCoV S genes, Fig. 1b), suggesting a recombination event as was hypothesized for the origin of TCoV [15]. A parallel evolution from a common ancestor with a much higher substitution rate on the S gene than on the rest of the genome can however not be ruled out at this stage.

Molecular comparison of the full genome of GfCoV/FR/2011 and avian gammacoronaviruses. a Phylogenetic analysis of the complete genomes of GfCoV/FR/2011 (in bold font) in relation to all available full genomes of turkey coronaviruses (TCoV) and full genomes of representative infectious bronchitis viruses (IBV) at the nucleotide level. The tree was generated using MEGA 5.05 and the maximum likelihood method. Bootstrap values (500 replicates) >75 are indicated on the nodes. b Simplot analysis of full genomic sequence for GfCoV/FR/2011 (query) and its closest TCoV (in blue) and IBV (in red) blast hits. The spike gene area is indicated on the plot (Color figure online)

The present study showed that GfCoV/FR/2011 harbours a genome organization very similar to that of TCoV strains. In addition, and again like TCoV, GfCoV/FR/2011 likely originated from a recombination event between an IBV-like (or TCoV-like) virus that would have given most of its genome and a so far unknown CoV that would have contributed by its spike gene. Despite the similarity of their genomes and their enteric tropism, TCoVs often cause mild clinical signs while GfCoVs are usually associated with extremely high mortalities in their host, suggesting strikingly different host–virus interactions. Further studies are ongoing to understand the host range of GfCoV/FR/2011 and its determinants of pathogenicity.

References

D. Gavier-widen, N. Decaro, C. Buonavoglia. in Infectious Diseases of Wild Mammals and Birds in Europe, ed. by D.J. Gavier-Widen, A. Meredith (Blackwell, 2012), pp. 234–240

J.F. Chan, K.S. Li, K.K. To, V.C. Cheng, H. Chen, K.Y. Yuen, J. Infect. 65, 477–489 (2012)

A. Balboni, M. Battilani, S. Prosperi, New Microbiol. 35, 1–16 (2012)

H. Chen, Y. Guan, X. Fan, Hong Kong Med. J. 17(Suppl 6), 36–40 (2011)

E. Liais, G. Croville, J. Mariette, M. Delverdier, M.N. Lucas, C. Klopp, J. Lluch, C. Donnadieu, J.S. Guy, L. Corrand, M.F. Ducatez, J.L. Guerin, Emerg. Infect. Dis. 20, 105–108 (2014)

J.G. Victoria, A. Kapoor, L. Li, O. Blinkova, B. Slikas, C. Wang, A. Naeem, S. Zaidi, E. Delwart, J. Virol. 83, 4642–4651 (2009)

F.E. Angly, D. Willner, A. Prieto-Davo, R.A. Edwards, R. Schmieder, R. Vega-Thurber, D.A. Antonopoulos, K. Barott, M.T. Cottrell, C. Desnues, E.A. Dinsdale, M. Furlan, M. Haynes, M.R. Henn, Y. Hu, D.L. Kirchman, T. McDole, J.D. McPherson, F. Meyer, R.M. Miller, E. Mundt, R.K. Naviaux, B. Rodriguez-Mueller, R. Stevens, L. Wegley, L. Zhang, B. Zhu, F. Rohwer, PLoS Comput. Biol. 5, e1000593 (2009)

H. Thorvaldsdottir, J.T. Robinson, J.P. Mesirov, Brief. Bioinform. 14, 178–192 (2013)

T. Hall, Nucleic Acids Symp. 41, 95–98 (1999)

R.C. Edgar, Nucleic Acids Res. 32, 1792–1797 (2004)

K. Tamura, D. Peterson, N. Peterson, G. Stecher, M. Nei, S. Kumar, Mol. Biol. Evol. 28, 2731–2739 (2011)

M.H. Gomaa, J.R. Barta, D. Ojkic, D. Yoo, Virus Res. 135, 237–246 (2008)

D. Cavanagh, J. Gelb Jr., in Diseases of Poultry, vol. 12, ed. by Y.M. Saif (2008)

M.M.C. Lai, S. Perlman, L.J. Anderson, in Fields Virology, 5th edn., vol. 1, ed. by D.M. Knipe, P.M. Howley (2007)

M.W. Jackwood, T.O. Boynton, D.A. Hilt, E.T. McKinley, J.C. Kissinger, A.H. Paterson, J. Robertson, C. Lemke, A.W. McCall, S.M. Williams, J.W. Jackwood, L.A. Byrd, Virology 398, 98–108 (2010)

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the ‘EPICOREM’ grant of the Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR), by the French Comité Interprofessionnel de la Pintade (CIP) and by the French Ministry of Agriculture. Etienne Liais is supported by a scholarship from French Ministry of Agriculture and Region Midi-Pyrénées. We would like to thank the Plateforme bioinformatique Toulouse Midi-Pyrénées, UBIA, INRA, 31326, Castanet-Tolosan, France; the GeT-PlaGe, INRA ENVT UMR444, Laboratoire de Génétique Cellulaire 31326, Castanet-Tolosan, France; and the Plateau de Génomique GeT-Purpan, UDEAR UMR 5165 CNRS/UPS, CHU PURPAN, Toulouse, France, for technical assistance with sequencing and sequence analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Edited By William Dundon

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ducatez, M.F., Liais, E., Croville, G. et al. Full genome sequence of guinea fowl coronavirus associated with fulminating disease. Virus Genes 50, 514–517 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11262-015-1183-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11262-015-1183-z