Abstract

When deciding where to visit next while traveling in a group, people have to make a trade-off in an interactive group recommender system between (a) disclosing their personal information to explain and support their arguments about what places to visit or to avoid (e.g., this place is too expensive for my budget) and (b) protecting their privacy by not disclosing too much. Arguably, this trade-off crucially depends on who the other group members are and how cooperative one aims to be in making the decision. This paper studies how an individual’s personality, trust in group, and general privacy concern as well as their preference scenario and the task design serve as antecedents to their trade-off between disclosure benefit and privacy risk when disclosing their personal information (e.g., their current location, financial information, etc.) in a group recommendation explanation. We aim to design a model which helps us understand the relationship between risk and benefit and their moderating factors on final information disclosure in the group. To create realistic scenarios of group decision making where users can control the amount of information disclosed, we developed TouryBot. This chat-bot agent generates natural language explanations to help group members explain their arguments for suggestions to the group in the tourism domain [more specifically, the initial POI options were selected from the category of “Food” in Amsterdam (see Sect. 3.2 for the details)]. To understand the dynamics between the factors mentioned above and information disclosure, we conducted an online, between-subjects user experiment that involved 278 participants who were exposed to either a competitive task (i.e., instructed to convince the group to visit or skip a recommended place) or a cooperative task (i.e., instructed to reach a decision in the group). Results show that participants’ personality and whether their preferences align with the majority affect their general privacy concern perception. This, in turn, affects their trust in the group, which affects their perception of privacy risk and disclosure benefit when disclosing personal information in the group, which ultimately influences the amount of personal information they disclose. A surprising finding was that the effect of privacy risk on information disclosure is different for different types of tasks: privacy risk significantly impacts information disclosure when the task of finding a suitable destination is framed competitively but not when it is framed cooperatively. These findings contribute to a better understanding of the moderating factors of information disclosure in group decision making and shed new light on the role of task design on information disclosure. We conclude with design recommendations for developing explanations in group decision-making systems. Further, we propose a theory of user modeling that shows what factors need to be considered when generating such group explanations automatically.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Have you ever been to lunch with other colleagues on a business trip? Do you recall how long it took to pick a restaurant? Imagine you start walking to one restaurant only to discover that person A wants to eat Halal, person B has an auto-immune protocol diet, and person C prefers a low-budget place. After visiting a restaurant, your group might also need to pick where to go next (e.g., a war museum, a cannabis store, etc.). Not only is it challenging to cater to multiple preferences, it can also be difficult to surface individual preferences in order to make an informed group decision! Recommender systems are decision-support systems that help users identify one or more items that satisfy their requirements. Most often, recommender systems propose items to individual users. However, in many domains, such as music (Najafian and Tintarev 2018) and tourism (Cao et al. 2018; Najafian et al. 2020a), people often consume recommendations in groups rather than individually and need support for group decision making. Several approaches in the literature (Masthoff 2004, 2015; Najafian et al. 2020a) propose social choice strategies that combine the individual preferences of all group members and predict an item that is suitable for the group. However, in every recommendation, some individuals might not be happy with the recommendation. For example, the Fairness Strategy (a social choice-based aggregation strategy) (Masthoff 2004) might recommend an item that one or more group members do not like but will recommend other items that they do like to compensate.

In these situations, explanations can clarify such trade-offs, help people comprehend how these recommendations are generated, make it easier to accept items they do not like, and ultimately facilitate reaching a consensus in groups (Najafian and Tintarev 2018; Felfernig et al. 2018; Barile et al. 2021; Tran et al. 2019). However, in the context of group recommendations, formulating explanations is even more challenging as other aspects must be considered. One of those aspects is privacy. Explaining why certain items are recommended can help users agree on a joint decision within a group (Felfernig et al. 2018; Ntoutsi et al. 2012), but the value of such explanations should be weighed against the desire to preserve individuals’ privacy by not disclosing information they do not want to disclose to the group (Najafian and Tintarev 2018; Najafian et al. 2020a, b, 2021a, b). Our ultimate purpose is to help people with better group decision making by providing them with privacy-preserving explanations to use in their negotiations.

The research gap lies in understanding the impact of privacy concerns on people’s willingness to disclose personal information in group decision-making settings. Although several studies have investigated the effects of different factors on people’s perception of privacy risks in disclosure scenarios (Malhotra et al. 2004; Nissenbaum 2004; Knijnenburg et al. 2013), there is little research investigating the relationship between people’s privacy attitudes and their actual disclosure behavior in group decision-making settings. This is particularly relevant for group recommender systems, where the recommendation is based on the aggregation of the group members’ preferences. Our research aims to fill the gap in the literature regarding the relationship between people’s privacy attitudes and their actual disclosure behavior in group decision-making settings, particularly in the context of group recommender systems.

In a previous online experiment with real groups, we investigated the effects of three factors on people’s privacy risk when disclosing personal information in the tourism context (Najafian et al. 2021a). We found that group members’ personalities (using the ‘Big Five’ personality traits), their preference scenarios (i.e., whether their preferences are aligned or not aligned with the preferences of the majority in the group), and the type of relationship they have in the group (i.e., loosely coupled heterogeneous like colleagues, versus tightly coupled homogeneous like friends) have a strong influence on people’s perception of disclosure risk. In a follow-up experiment, we investigated the effects of these factors on people’s disclosure behavior (how they choose, if any, among the certain types of personal information to share with their group members) (Najafian et al. 2021b). Although we expected to see the opposite effect of factors on information disclosure (i.e., if a factor increases user privacy risk, it decreases their information disclosure), neither the personality traits nor the preference scenario affected people’s information disclosure. However, upon further investigation, we found that the task design (whether group members were instructed to convince other group members of their opinion, or not) affected participants’ information disclosure.

Therefore in this work, we investigate what other mediating factors might cause this gap between people’s privacy attitudes compared to their actual disclosure behavior. For example, could it be that perceived privacy risk (i.e., the expectation of losses associated with the disclosure of personal information to the group) and disclosure benefit (i.e., the extent to which users believe disclosing their personal information to their group members is beneficial for the group decision or their negotiation position) mediate the effect on participants’ actual disclosure behavior. Several studies show that when people want to decide on personal information disclosure, they trade off the anticipated benefits with the risks of disclosure (e.g., Taylor et al. 2009), which is known as “privacy calculus” (Culnan 1993; Laufer and Wolfe 1977). Besides, in the group recommendation context, this effect might depend on the task design (whether the task is designed as a competitive or cooperative task). This thorough investigation of the dynamics between these factors and disclosure will result in a theory of user modeling that may inform considerations for generating group explanations automatically.

In this study, we find the intermediate factors that ultimately affect individuals’ disclosure behavior from more general to more specific. Note, for this study, the relationship type among group members in all conditions is predefined as a “loosely coupled (weak ties) heterogeneous group” (e.g., a lecturer and students) to consider privacy concerns in an extreme case (see Sect. 3.3 for more details). Results show that participants’ personalities and whether their preferences align with the majority affect their perception of general privacy. This, in turn, affects their trust in the group, which affects their perception of privacy risk and disclosure benefit, which ultimately influence the amount of personal information they disclose in a group. We also find that privacy risk is a significant predictor when people are exposed to the competitive task but is not for the cooperative task.Footnote 1

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 introduces relevant literature on what affects the trade-off to disclose personal information in a group recommendation context and presents the hypotheses that lead this work. Section 3 presents the user experiment performed to investigate the privacy aspects of explaining recommendations to groups. Section 4 presents the results and analysis of our user experiment, while Sect. 5 discusses the main findings, presents the limitations of our approach, and provides recommendations for future work. Finally, Sect. 6 summarizes our findings.

2 Theoretical framework and hypothesis development

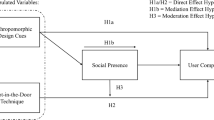

When people are in a situation where they have to decide where to visit next in group traveling, they might have to make a trade-off between: (a) disclosing their personal information to explain and support their arguments about where to visit or where to skip (i.e., this place is too expensive for my budget), and (b) not violating their privacy by disclosing too much. In this section, we discuss relevant literature and theoretical background on what factors affect the trade-off to disclose personal information in a group. Further, we develop a conceptual model to understand the relationship between those factors as shown in Fig. 1. Our model builds upon the single-user recommender systems evaluation framework proposed by Knijnenburg et al. (2012), which has found widespread use in the field of recommender systems (800+ citations), and has particularly been adapted to privacy-related studies in previous work as well (Mehdy et al. 2021; Kobsa et al. 2016; Knijnenburg and Kobsa 2013). This framework suggests that user behavior is influenced by objective system aspects, personal and situational characteristics, and subjective system aspects.Footnote 2 In our study, we extend this framework to the context of group recommendations, focusing specifically on the trade-off between personal information disclosure and privacy in group decision making. We utilize the higher-level concepts from the Knijnenburg et al. (2012) framework, including personal and situational characteristics, objective and subjective aspects, and actual behavior, to understand how individuals make decisions about personal information disclosure in a group context. We do not use the lower-level operationalized factors from the Knijnenburg et al. (2012) framework since they are not directly applicable to our research question. Our core variables in the context of group decision making/recommendations are established as follows: personal characteristics of group members (i.e., their personality), situational characteristics with regards to the group (i.e., preference scenario), objective aspects (i.e., task design), subjective aspects (i.e., their perceived risk when disclosing certain personal information in the group), and actual behavior of group members (i.e., when group members disclose their personal information in the group). Following, we go into detail about every single variable, starting with the main outcome variable “information disclosure”.

2.1 Antecedents of information conflict of interest

As one of the most prominent information privacy research frameworks, the privacy calculus theory examines information disclosure as a decision in which people trade off risks against benefits (Culnan and Armstrong 1999). Based on privacy calculus theory, the antecedents of information disclosure are disclosure benefits and privacy risk. In the privacy calculus framework, perceived privacy risk is the degree to which people believe there is a potential for loss associated with the release of personal information (Dinev et al. 2006) and benefits are the context-specific gains individuals expect in exchange for the information they provide (Jozani et al. 2020).

2.1.1 Conflict of interest benefit

People may respond differently to information disclosure based on their assessment of inherent trade-offs of risks and benefits. In our context (tourism group decisions/recommendations), perceived disclosure benefit refers to “the extent to which users believe disclosing their personal information to their group members is beneficial for the group decision or for their own negotiation position within the group”. If the users feel that they get some benefits, then they will give up some level of their privacy in return for the perceived benefits (Smith et al. 2011; Xu et al. 2013; Choi et al. 2018; Kim et al. 2019). Thus, we hypothesize:

H1 Participants who perceive a higher level of disclosure benefit are more likely to disclose their personal information.

2.1.2 Privacy risk

On the other hand, perceived risks include all the problems and difficulties that the users might face when the other parties have access to their personal information. Perceived privacy risk in our context can be defined as the “expectation of losses associated with the disclosure of personal information in the group”, adapted from Xu et al. (2008)’s definition for online providers. Therefore, if users perceive that they are at risk when they disclose their personal information, this can decrease their willingness to share information with online providers (Keith et al. 2013; Malhotra et al. 2004; Norberg et al. 2007). For example, Keith et al. (2013) found that increased perceived privacy risk from a mobile application decreases users’ intention to share personal information, including location and financial information. Thus, we hypothesize:

H2 Participants who perceive a higher level of privacy risk are less likely to disclose their personal information.

As can be seen by hypotheses 1 and 2 (H1 and H2), there is a tension between the perceived benefit of disclosing personal information and the degree of risk individuals perceive by disclosing their information in the group: depending on the situation, if people find that the benefit of disclosing their information outweighs the involved risk, they will disclose the information. Otherwise, they will not disclose their information in the group.

2.2 Antecedents of conflict of interest benefits

Perceptions of benefit can be affected by different factors. Milne and Gordon (1993), delineate cost-benefit perceptions of information exchange and indicate that some consumers do not mind revealing private information to a company if they receive specific benefits for providing the information. The benefit is context-dependent, and one’s evaluation of benefit is influenced by (a) the amount of trust the individual has in the receiver (or in our group recommender context, the group) (Rohm and Milne 2004; Shin 2010a), (b) the preference scenario (for example, having minority or majority preferences compared to other group members) (Najafian et al. 2021a), and (c) the task design (for example, whether group members were instructed to convince other group members of their opinion, or not) (Toma et al. 2013; Toma and Butera 2015). For example, if an individual is in the minority position, disclosing more information may help support their arguments to the group compared to an individual in the majority who does not have to make that effort. We address each of these in turn:

2.2.1 Trust in group

Trust has mainly been studied in single user contexts, e.g., trust in an app or an institution to which users disclose their information. In such contexts, Kehr et al. (2015) showed that trust positively affects the perceived benefits of disclosing information. We assume this can be similar to trust in a group with whom one travels. For example, when group members trust the other individuals in the group then they will perceive a lower risk, and hence greater benefits in providing their personal information (Rohm and Milne 2004; Shin 2010a). Thus we hypothesize:

H3 Participants who perceive a higher level of trust in the group members perceive higher levels of disclosure benefit.

2.2.2 Task design

The competitive or collaborative nature of task design often influences group member behavior and has previously been explored in group decision-making literature (Toma et al. 2013; Toma and Butera 2015). Notably, the competitive mindset often urges group members to share information with the goal of ‘winning’ the discussion to be ‘right’ (Hofmann 2015; Toma et al. 2013). This competitive mindset might influence group members to share more information to reach a group decision that matches their preferences. Similarly, Najafian et al. (2021b) found when people had to convince other group members, they disclosed more information compared to when they did not have to convince other group members. This can suggest that a cooperative mindset, where members do not feel the urge to convince other group members, might influence group members to perceive less benefit of sharing their personal information. Although from a theoretical standpoint, the hypothesis that ‘a cooperative mindset would also increase perceived benefit’ is probably sound too, preliminary results suggest that a competitive scenario results in more disclosure. Therefore empirical work is needed to identify which effect is stronger. Thus we hypothesize:

H4 Participants who have been told that the group decision is a competitive task perceive a higher level of disclosure benefit than participants who have been told to address the decision as a cooperative task.

2.2.3 Preference scenario

The “preference scenario” in this study represents whether the active user’s preferences are in the minority or majority within the group. People whose preferences are in the minority may perceive more benefit from providing the group with reasons behind their preferences than those whose preferences are in the majority. In our study, we consider triads (a group containing three members) to explore this parameter. Thus we hypothesize:

H5 Participants whose preferences are in the minority perceive higher disclosure benefits compared to participants in both majority scenarios. We mention “both majority scenarios”, because when the social positions of the group members are not equal, the majority scenario itself can also have two conditions, depending on whether the other member has the same preference as the participant. In our study, we consider one other group member to be a peer of the user and the other group member to be a superior. When the participants’ preferences are in line with their superior and opposite to their peer (which we call “boss majority”), this will have different social implications than when the participants’ preferences are in line with their peer and opposite to their superior (which we call “peer majority”).

2.3 Antecedents of privacy risk

Above, we looked at factors contributing to perceived disclosure benefits—a perception that should increase disclosure. Now we look at factors that contribute to perceived privacy risk—a perception that, in contrast, should decrease disclosure. Risk has been defined as uncertainty resulting from the potential for a negative outcome (Havlena and DeSarbo 1991), and one’s evaluation of risk is influenced by (a) the amount of trust the individual has in the receiver (or in our group recommender context, the group) (Rohm and Milne 2004; Shin 2010a), and (b) the preference scenario (for example, having minority or majority preferences compared to other group members) (Najafian et al. 2021a). Further, trust in group is influenced by one’s general privacy concern perception (Kehr et al. 2015), and finally one’s general privacy concern is influenced by one’s personality (Korzaan and Boswell 2008; Junglas et al. 2008; Bansal et al. 2016; Najafian et al. 2021a). We address each of these in turn:

2.3.1 Trust in group

Trust has been addressed by a number of prior studies and is generally viewed as a type of belief that users can confide on certain entities to protect their personal information (Malhotra et al. 2004). Trust is an important factor that can negate the effects of perceived risk (Ioannou et al. 2020; Krasnova et al. 2010). If trust is established in the mind of the users, then they will perceive a lower risk in providing their personal information (Rohm and Milne 2004; Shin 2010a). In the context of group decisions/recommendations, when group members trust the other individuals in the group they are more willing to accept personal vulnerability, and consequently perceive less privacy risk (Mayer et al. 1995; Kweekel et al. 2017). Previous studies have demonstrated that perceived trust is positively related to reducing the privacy risks of personal information disclosure (Shin 2010b; Kumar et al. 2018; Nemec Zlatolas et al. 2019). Thus, we hypothesize:

H6 Participants who have a higher level of trust in the other group members perceive lower levels of perceived privacy risk.

2.3.2 Preference scenario

Several studies suggest that the relative preferences of group members (i.e., the preference scenario), could impact the privacy risk. In particular, people whose preferences are in the minority within the group could decide not to share their preferences to match the opinions of the majority, for a phenomenon known as conformity (Forsyth 2018; Asch 1956; Masthoff 2011). This was confirmed in a recent empirical study, which showed that people who have minority preferences expressed higher privacy concerns (Najafian et al. 2021a). The majority scenario itself can also have two conditions when the social positions of the group members are not equal as described above (“boss majority” and “peer majority”). Thus, we hypothesize:

H7 Participants whose preferences are in the minority perceive higher levels of privacy risk compared to participants in both majority scenarios.

2.3.3 General privacy concern

General privacy concern is a personal trait that represents an individual’s general tendency to worry about information privacy (Kehr et al. 2015). Several studies have shown that privacy concerns can significantly reduce trust between consumers and companies as privacy concerns decrease trust (Van Dyke et al. 2007; Culnan and Armstrong 1999). Thus, we hypothesize:

H8 Participants with a higher level of general privacy concern have less trust in their group members.

2.3.4 Personality

Several studies in the field of behavioral sciences have analyzed the impact of personality on an individual’s general privacy concern perception (Korzaan and Boswell 2008; Junglas et al. 2008; Bansal et al. 2016). The results, however, are not consistent with each other. Personality is generally modeled using the Five Factors Model (FFM), also known as the Big Five or OCEAN. It models individuals’ personalities with five traits: Openness, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism (Costa and McCrae 1992a). Bansal et al. (2016), analyzed the effect of an individual’s personality on privacy concern in three classes of websites (Finance, E-commerce, and Health). Their results showed a significant positive impact of Agreeableness and Neuroticism on privacy concerns. In the context of location-based services, Junglas et al. (2008), showed significant effects of Agreeableness on privacy concern but suggested a negative impact (i.e., more agreeable people were less concerned about their privacy). In the context of explanations for group recommendations, we found that more agreeable and extroverted people were more concerned with privacy (Najafian et al. 2021a). Following, we describe each trait in more detail.

Extraversion is a personality dimension linked to being warm, sociable and assertive (Anastasi and Urbina 1997; Costa and McCrae 1992b). Extraverts are also reported to have lower information sensitivity concerns, so as to accommodate their higher need to interact (Bansal and Gefen 2010). Therefore, extraversion should be negatively related to user privacy concerns (Pentina et al. 2016). Thus, we hypothesize:

H9 Extraversion affects participants’ general privacy concern perception.

Agreeableness “involves getting along with others in pleasant, satisfying relationships” (Palmer et al. 2000). Highly agreeable individuals have been found to be less suspicious of their environment or other individuals (Costa and McCrae 1992a). Although warm and trusting in their social interactions, agreeable individuals consider such behaviors risky (Chauvin et al. 2007). Because privacy invasion is a deviant social behavior, some argue that individuals with this trait are more concerned about their privacy than are others (e.g., Junglas et al. 2008; Bansal et al. 2016). On the other hand, some other studies argue that agreeable individuals are less likely to appraise others’ actions as potentially harmful when faced with privacy threats (e.g., Korzaan and Boswell 2008). Even though all the mentioned studies found a significant effect of this trait on privacy concern, the direction was not consistent. Thus, we hypothesize:

H10 Agreeableness affects participants’ general privacy concern perception.

Conscientiousness is a personality dimension that emphasizes competence, achievement, self-discipline, and dutifulness (Anastasi and Urbina 1997). Conscientious individuals have more precaution and foresight, are detail-oriented, and investigate various consequences of a decision, as well as being better able to identify potential hazards of disclosing private information (Bansal and Gefen 2010). So as conscientious individuals tend to be deliberative, give more attention to details, and pay close attention to others’ actions, they would also manifest greater concern for protecting their privacy (Pentina et al. 2016). Thus, we hypothesize:

H11 Consciousness affects participants’ general privacy concern perception.

Neuroticism is a personality dimension characterized by anxiety, self-consciousness, and impulsiveness (Anastasi and Urbina 1997). It is sometimes referred to as emotional instability, or if reversed as emotional stability (e.g., Bansal et al. 2016). In the remainder of this study, we will use the term “neuroticism” as it is the most widely used one. A person with a higher level of anxiety and fearfulness should be more nervous about disclosing their personal information and have a greater privacy concern. A significant and positive effect of neuroticism on privacy concern was found in multiple domains (Bansal et al. 2016). Thus, we hypothesize:

H12 Neuroticism affects participants’ general privacy concern perception.

Openness to new experiences relates to an individual’s curiosity, intellect, fantasies, ideas, actions, feelings, and values. Individuals scoring high on this personality trait tend to be less conforming to norms and to have untraditional and widespread interests (Anastasi and Urbina 1997). They were found to show a high level of scientific and artistic creativity, divergent thinking, liberalism, and only little religiosity (Junglas et al. 2008). Therefore, and compared to others, open individuals have developed a broader and deeper sense of awareness. As a result of such awareness, they are more likely to be sensitive to things that are threatening (Junglas et al. 2008). Thus, we hypothesize:

H13 Openness affects participants’ general privacy concern perception.

3 Method

In this section, we describe an online, between-subjects study that investigates how antecedents of risk perception and perceived benefits relate to individuals’ trade-off between disclosure benefit (i.e., disclosing their personal information to explain and support their arguments) versus privacy risk (i.e., not violating their privacy by revealing too much) when disclosing their personal information (e.g., their current location, emotion information, etc.) in a group recommendation explanation. Namely, we investigate: an individual’s personality, trust in group, and general privacy concern as well as their preference scenario, and task design.Footnote 3

3.1 Study platform

To answer the research question, we implemented a web-based chat-bot that we call TouryBot. For the UI, we used a client in Java (Vaadin AI Chat)Footnote 4 and implemented in the Vaadin framework.Footnote 5 The backend is written in Python. SQLite was used for logging user interactions in the task. Tourybot includes two chat windows, one for the chat with the Group (see Fig. 2), and the other for the chat between the system bot and individual members (see Fig. 3). Users can seamlessly switch between the two conversations to add system-generated recommendations and explanations to their discussions with other group members.

The chat in the peer majority and competitive task scenario between an active user and their group. Shown are the two UI sections: a switching between two ongoing chats, one with a chat-bot and one with the group; and b TouryBot suggests a place (the Oriental City in this example) for the whole group, one active user (John) and his two hypothetical group members (e.g., Bob and Alice) in a group chat (TouryBot does not generate recommendations. It only represents the results from other platforms (e.g., Foursquare) for users to discuss their arguments regarding that recommended item within the group)

An example of chats where the active user is in the peer majority scenario (i.e., the user agrees with the majority preference with their peer) and is given a competitive task. Shown are the two UI sections: a switching between two ongoing chats, one with a chat-bot and one with the group; and b an ongoing chat with a chat-bot (TouryBot) where the user can indicate how much information they want to share to convince the other group member (Bob) to visit the suggested POI (the background color of the two chat windows (TouryBot chat vs. group chat) was selected to be different to help participants better differentiate between the two chats)

3.1.1 Manipulations

Inspired by previous works (Najafian et al. 2021a, b), our study considers two factors that may influence information disclosure using between-subjects manipulations: users’ preference scenario (3 conditions) and task design (2 conditions).

Preference scenario (binary) Each participant in our study was exposed to either the minority or one of two majority preference scenario types.

-

Minority: the active user’s preference is in the minority within the group. An item that is not the (active) user’s favorite has been suggested to the group by TouryBot.

-

Peer majority: the active user’s preference is in the majority within the group and against their superior. An item that is the user’s favorite has been suggested to the group.

-

Boss majority: the active user’s preference is in the majority within the group and in line with their superior. An item that is the user’s favorite has been suggested to the group.

The shown scenario was dummy coded into two dichotomous values for both minority and peer majority tested against the boss majority.

3.1.2 Task design (binary)

Each participant in our study was exposed to either a competitive or cooperative task design.

-

Competitive task: In this case, the participant tries to convince others to either skip or visit the recommended POI through privacy-sensitive explanations.

-

Cooperative task: In this case, the participant is only tasked to reach a decision in their group through privacy-sensitive explanations.

3.1.3 Measures

Personal information disclosure, disclosure benefit, privacy risk, general privacy concern, trust in group, personality, and demographics were measured mainly using existing instruments. Except for demographic and personal information disclosure questions, all items were assessed using a 5-point Likert scale with endpoints of ‘strongly disagree’ and ‘strongly agree’.

Personal information disclosure The primary dependent variable in our experiment is participants’ personal information disclosure decision in a tourism group recommendation. To decide which personal information to include in the study, we used personal information categories listed in Caliskan Islam et al. (2014), which were derived from users’ tweets on Twitter, and personal information used in Knijnenburg (2015), that used an online health application context. We included those that are relevant to a tourism recommender system context, namely the following personal information:

-

1.

Emotion-related information (i.e., you feel grief today, this place cheers you up)

-

2.

Location-related information (i.e., you are in the Vondelstraat, close to this place)

-

3.

Financial-related information (i.e., this place is cheap, fits your budget)

-

4.

Religion-related information (i.e., you only eat Kosher meals, which this place serves)

-

5.

Health-related information (i.e., this place serves low carb food, which fits your Paleo diet)

-

6.

Sexuality-related information (i.e., you identify as queer, and this place is in a gay neighborhood)

-

7.

Alcohol-related information (i.e., this place sells craft beers, which fits your drinking preferences)

Users chose among these seven types of personal information as to which ones to share with their group members. In the final analyses, we consider all the information types as sum scores for the primary model analyses (the value ranges between 0—when no information is disclosed at all—, to 7—when all information is disclosed—). We consider disclosure as a sum score since the sharing selections are not independent decisions (i.e., when participants do the disclosure, they see all the information types simultaneously in a randomized order).

3.1.4 Conflict of interest benefit

In our context, perceived disclosure benefit refers to the “extent to which users believe disclosing their personal information to their group members is beneficial for the group decision”. To measure disclosure benefit for disclosing each type of information, we created seven questions, one for each of the seven personal information types that we included in the study as follows:

I think disclosing my emotion-related information to these group members is beneficial for the group decision.

The emotion-related information above was adapted based on the type of information asked. For the final analyses, the average disclosure benefit is centered on having a value between \(-2\) and 2.

3.1.5 Privacy risk

Perceived privacy risk in our context is defined as the “expectation of losses associated with the disclosure of personal information in the group”. To measure privacy risk for disclosing each type of information, we created seven questions, one for each of the seven personal information types that we included in the study as follows:

I think disclosing my emotion-related information to these group members is too sensitive for this type of group.

The emotion-related information above was adapted based on the type of information asked. For the final analyses, the average privacy risk is centered on having a value between \(-2\) to 2.

General privacy concern This privacy concern is a personal trait pertaining to how concerned one is in general regarding their privacy. To measure general privacy concern we used the 8-item scale developed in Knijnenburg and Kobsa (2014) (listed in Table 1). Note this factor is scaled to have a variance of 1 in the final model.

Trust in group By adopting the trust definition in Mayer et al. (1995) to our context, the trust one individual has for another in the group can be defined as “the willingness of an individual to be vulnerable to the actions of other individuals by disclosing their personal information”. To measure the active user’s trust toward their group members, we adapted the items from previous research (Tanghe et al. 2010; Joinson et al. 2010; Norberg et al. 2007) as shown in Table 1. Note this factor is scaled to have a variance of 1 in the final model.

Factor loading of the included items for measuring general privacy concern and trust in group are shown in Table 1, as well as Cronbach’s alpha and average variance extracted (AVE) for each factor. The model has a good model fit: \(\chi ^2\)(64) = 271.991, \(p < 0.001\); root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA) \(=.079\); 90% CI: [0.070, 0.089], Comparative Fit Index (CFI) = 0.986, Turker–Lewis Index (TLI) = 0.983. All included items have a higher factor loading than the recommended value of 0.40 (Knijnenburg and Willemsen 2015). Values for both Cronbach’s alpha and AVE are good, indicating convergent validity, and the square root of the AVE is higher than the factor correlation, indicating discriminant validity of the two factors. The two factors are correlated with \(r=-0.412\) (significant at \(p<0.001\)).

Personality (continuous) We used the Big Five Inventory (BFI) to assess individuals’ personality on the five traits of Openness, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism (John and Srivastava 1999). The questionnaire is composed of 44 questions with a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Responses are aggregated by taking their mean.

Descriptive measures We collected participants’ age, self-identified gender, and nationality to enable a demographic description of our sample.

3.2 Materials

We needed some Places of Interest (POIs) in Amsterdam to elicit participants’ preferences for the user study. To collect such POIs and make sure they somewhat fit participants’ true preferences, we provided them with three initial POIs to rank. One POI among these three initial POIs was selected to recommend to the group in the TouryBot based on an active user’s ranking on the three initial POIs. To encourage disclosure, we always recommended the active user’s top choice in the majority scenario, and for the minority scenario, we recommended the user’s least favorite place. The three initial POI options were retrieved from the most frequently visited POIs in the city of Amsterdam from the category of “Food”, from the social location service Foursquare.Footnote 6 Using participants’ actual preferences, we aimed to increase the likelihood of a more realistic situation for users to imagine.

3.3 Procedure

Participants received brief instructions about the task and were asked to check off an informed consent before beginning their task session. After consent for the study, participants went through the following steps.

Step 1: “Group formation”. Participants were asked for their first name and to form their (hypothetical) group by naming two people they might be in a group with whom they are not close. Further, participants were instructed to name members so that the social positions of the group members were not equal (e.g., a student planning a trip with a lecturer and another student or an employee planning a trip with a manager and another employee). This way, participants were in a hypothetical group with a “peer” and a “boss”. Note the relationship type among group members was (in all cases) predefined as a “loosely coupled (weak ties) heterogeneous group” as described above (e.g., a lecturer and students).Footnote 7 Note that the group always consisted of three group members, where only one is the active user and two are hypothetical group members.

Step 2: “Preference Elicitation”. We also approximated active user preferences by asking them to rank three POIs in Amsterdam as described in Sect. 3.2.

Step 3: “Group Discussion”. Participants were randomly assigned to participate in one of our six scenarios (3 preference scenarios * 2 task designs).

Only one active user shares personal information to support their arguments in our setup. Depending on whether the current user is in the minority situation or one of the two majority situations, they were tasked to convince other group members to skip or visit the suggested place in the competitive task design, or they were assigned to reach a decision in all three preference scenarios in the cooperative task design by disclosing personal information. As can be seen in Fig. 2, in the group chat window, the recommendation came from the system (TouryBot). This recommendation was based on the majority vote aggregation function in the group. After TouryBot suggested a restaurant for the group, the given active user was asked to switch to the TouryBot chat window. As can be seen in Fig. 3, in the TouryBot chat window, the user was presented with different personal information options to support their arguments to the group (the background color of the two chat windows (group chat vs. TouryBot chat) was selected to be different to help participants better to differentiate between the two chats). They could choose which information (if any) that they wanted to share with their group to either persuade them or reach a decision with them. They could dynamically see the preview of the information to be shared with their group based on their choices. After they shared as much (if any) information as they wanted with their group members, the scenario ended with one of the hypothetical group members saying, “Okay, let’s skip/visit this place”. Then the participant was redirected to a questionnaire.

Step 4: “Questionnaire”. After completing the chat-bot activity, participants were asked a set of questions to assess their perceived general privacy concern, trust in the group members, personality traits, privacy risk, and disclosure benefit as described in Sect. 3.1.3.

4 Results

This section discusses the outcomes of the hypothesis tests and presents exploratory findings.

4.1 Participants

To determine the required sample size, we performed a power analysis (Dattalo 2008) of a small-sized effect (0.2 SD) with a power of 85\(\%\) in a between-subjects experiment. It showed that a minimum of 277 participants were needed in total. This was in line with the suggested minimum sample size for SEM in Knijnenburg et al. (Knijnenburg and Willemsen 2015) (minimum 200 participants).

We recruited 280 participants from the crowdsourcing platform Prolific.Footnote 8 This platform has shown to be an effective and reliable choice for running relatively complex and time-consuming studies (e.g., for interactive information retrieval) (Xu et al. 2020). To ensure reliable participation, we followed Prolific guidelines and restricted eligibility to workers who had an acceptance rate of at least 80% and had at least ten successful submissions on the platform. We paid participants the wage suggested by Prolific. We included three attention checks in the study, for example, “This is an attention check. Please select Neutral.” We excluded from our results participants who failed at least one attention check (two participants were excluded from the results). The resulting sample of 278 participants had an average age of 25.8 (sd = 7.5) with a satisfactorily balanced gender distribution (\(49\%\) female, \(50\%\) male, and \(1\%\) other).

4.2 Hypothesis tests

The resulting SEM model (Table 2) shows how privacy risk and disclosure benefit and their antecedents influence personal information disclosure in groups. Based on the final results, all the question items to measure general privacy concern and trust in group (see Sect. 3) remained valid. The model has a great model fit: chi-square(204) = 364.150, \(p < 0.001\); root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA) \(=.053\); 90% CI: [0.044, 0.062], Comparative Fit Index (CFI) = .987, Turker–Lewis Index (TLI) = .992. We looked at the disclosure and respective privacy risk and disclosure benefit as an average rather than on an individual item level because when people do the disclosure, they see all the information types simultaneously and probably reason about what they will disclose (not independent decisions).

The structural equation model (SEM) for the data of the experiment. The model shows the objective and subjective factors behind users’ information disclosure decisions when using a group recommender system, and the effect of personal and situational characteristics (significance levels: *** \(p <0.001\), ** \(p <0.01\), * \(p <0.05\), ‘ns’ \(p >0.05\))

The results show that the relationship between average disclosure benefit and overall disclosure is significant (\(\beta = 0.927\), \(p < 0.001\)), supporting H1. Furthermore, a significant negative interaction effect of average privacy risk and task design on overall disclosure can be observed (\(\beta = -0.420\), \(p = 0.043\)). This finding suggests that when average disclosure benefit seems to be the same (as there is a weak but strongly significant correlation between the average disclosure benefit and average privacy risk, \(\beta = -0.080\), \(p < 0.001\)), average privacy risk has a significantly stronger effect when it is a competitive task versus a cooperative task on the overall disclosure. Given that we have a significant interaction effect, the main effects cannot be interpreted in isolation. Therefore H2 is supported, but with the caveat that it depends on task design (Sect. 4.3 describes the interaction effect of risk and task design on disclosure in more detail).

Besides, task design is not a significant predictor of average disclosure benefit (\(\beta = 0.035\), \(p = 0.566\)), and therefore, H4 is not supported. Considering preference scenarios, it is not a significant predictor of average disclosure benefit (\(\beta = 0.102\), \(p = 0.161\)) or average privacy risk (\(\beta = 0.079\), \(p = 0.341\)), and H5 and H7 are not supported respectively. Furthermore, the analysis results show that trust in group has a significant impact on both average disclosure benefit and average privacy risk, supporting H3 (\(\beta = 0.178\), \(p < 0.000\)), and H6 (\(\beta = -0.123\), \(p < 0.000\)). Moreover, general privacy concern negatively affects trust in group (\(\beta = -0.358\), \(p < 0.000\)), supporting H8. We found that high levels of the agreeableness trait also has a significant positive effect on trust in group (\(\beta = 0.338\), \(p = 0.004\)).

The analysis results indicate that three out of five types of personality traits (extroversion, agreeableness, and conscientiousness) are related to general privacy concern (the first two negatively and the last positively), supporting H9 (\(\beta = -0.536\), \(p < 0.001\)), H10 (\(\beta = -0.629\), \(p < 0.001\)), and H11 (\(\beta = 0.550\), \(p < 0.001\)). However, the relationship between the other two personality traits (neuroticism, and openness) and general privacy concern is not significant, and so H12 (\(\beta = 0.093\), \(p = 0.301\)) and H13 (\(\beta = -0.154\), \(p = 0.272\)) are not supported. Additionally, minority preference scenario is found to have a significant positive relationship with general privacy concern (\(\beta = 0.386\), \(p = 0.018\)). Figure 4 summarizes the final model.

We commit to make all data and code publicly available for the community to be able to replicate and reproduce our study and results.Footnote 9 However, the raw results of our user study are anonymized, i.e., we do not publish participants’ identifiable information such as user IDs.

4.3 Exploratory findings

Here, we present several exploratory findings that may help explain the results of the hypothesis tests.

4.3.1 Interaction effect of risk and task design on disclosure

Figure 5 visualizes the distribution of perceived average privacy risk (x-axis) and the corresponding overall information disclosure (y-axis) in two different tasks (competitive vs. cooperative), with estimated regression lines. As seen in the figure, in line with our findings, there is a negative slope for the cooperative task between overall disclosure and perceived privacy risk, but this slope is smaller than it is for the competitive task.

4.3.2 Conflict of interest behavior per item

Here we look at each item individually to see how much of each type of information that participants disclosed and how much benefit and risk they perceived regarding it. As can be seen in Table 3, people disclosed location and financial the most (\(75\%\) and \(62\%\) respectively) and sexuality and religion the least (\(10\%\) and \(9\%\)). Among all seven information types, it seems people found the location, health, financial, emotional, and alcohol information more beneficial for this context to share with group members (disclosure benefit \(\ge 3\)). They perceive more privacy risks when disclosing emotional and sexual information (privacy risk \(> 3\)).

4.4 Qualitative feedback

Participants distinguished between the cooperative and competitive tasks in their qualitative comments. For example, in the cooperative task, when they were asked why they disclosed certain information, some of them explicitly mentioned a group goal as shown below:

“Because it can help in making an efficient decision.”, “Make them aware of my whereabouts, so they come to make the right decision.”, “It is practical information that might help in choosing the right attraction sites for the group.”, or “If you know/trust the group, you can help them decide where to go.”. “Nowadays more and more people start to live a healthier life so disclosing health-related information could be very useful to make a decision.”.

Comparatively, in the competitive task, people seemed to follow a more self-serving/egocentric goal to either not disclose or disclose certain information. Some examples include the following: “I don’t think it’s fair to persuade someone to go somewhere based on my location as opposed to theirs. But if we all had the same location roughly, that would be fine.”, “Everyone is different, and what might be classed as the perfect diet to one person may be viewed as boring and restrictive to others, therefore I didn’t feel this was a valid argument in this case as I didn’t know the people.”, “I think they wouldn’t care and would just think I’m too picky.”, “Health is extremely important, and I would not be willing to put myself in a situation where something will compromise my health.”, or “As for the religion subject, even if it’s personal, it has a big interest since it could stop me from eating or could lead to me getting sick.”.

User comments indicate that they saw the task as competitive or cooperative and that this informed the reasoning behind the disclosure. This can inform design regarding formulating tasks in group recommender systems (e.g., focus on consensus and cooperation when asking people for personal information).

5 Discussion

The study results provide exciting insights into users’ personal information disclosure decisions in a tourism group decision/recommendation context. They also demonstrate how personal privacy concerns, and manipulated situational and objective factors influence the decision process. In this section, we reflect on these results, their design implications, and the limitations of our study.

5.1 Implications

5.1.1 Establishing trust in the group is essential

Conflict of interest is a trade-off between risk and benefit that is rooted in trust. When people have to decide where to visit next while traveling in a group, the decision-making facilitator like the one we proposed performs better if trust in the group is high. In that case, people perceive less privacy risk and more disclosure benefit and ultimately disclose more personal information to help group decision making. It has also been shown that higher degrees of trust at the individual and group levels help group members implement more effective and meaningful processes to make collective decisions (Sapp et al. 2019). Thus, we recommend making sure to establish trust within the group beforehand. There are suggestions in different domains to facilitate trust and active participation among group members by, for example, taking their opinions on the decisions into account (Kumar and Saha 2017).

5.1.2 Interaction effect of risk and task design on disclosure

Although we expected to see an effect of task design on disclosure benefit, we only found a significant negative interaction effect of average privacy risk and task design on overall disclosure. It could be that for the selected task design in this study (or how the two task types were operationalized), users did not perceive any distinguishable difference in the benefit of disclosing their information. Future work should investigate this with different types of task design or even the same ones with different formulations. Regardless, the current study shows that how the group decision task is framed (i.e., cooperative or competitive) can have a substantial impact on how people make privacy decisions—in particular, it influences the importance of risk in the decision. While the average level of privacy risk was roughly the same (2.7 out of 5) between participants in the competitive and cooperative task conditions, there is a significant interaction effect of task design and privacy risk on information disclosure: privacy risk has a significantly stronger effect on the disclosure decision when it is framed as a competitive task (as compared to a cooperative task).

A potential explanation for this effect could be that the cooperative task was viewed as having a more altruistic goal, while the competitive task was seen as having a more self-serving goal, as can be seen through participants’ qualitative feedback in Sect. 4.4. In the competitive task, the information disclosure is thus for one’s own benefit, hence people will weigh their personal risk regarding the information disclosure with how much benefit they think they are going to get out of this disclosure. Toma and Butera (2015) stated that competition activates the fear of being exploited (risk vulnerability), but also the desire to exploit other people. They also add, in all information exchange situations, competition activates tactical deception tendencies aimed at maintaining a positive self in other people’s eyes (Toma and Butera 2015). In contrast, when people regard the information disclosure as benefiting the group (i.e., in the cooperative task), then it seems one’s own privacy risk becomes a less critical factor which leads to more disclosure—one that can be sacrificed for the good of the group.Footnote 10 In line with this, user comments give us an idea of how to formulate tasks in group recommender systems. As such, when designing for situations where disclosure is crucial for the success of a system, designers should emphasize cooperative aspects of the system’s goal in their communication to the users (e.g. “Help make the recommendations better by providing some information about you / your preferences”). However, future work should explore this phenomenon when eliciting information with higher sensitivity.

5.1.3 Effect of preference scenario on general privacy concern

Although we expected that the preference scenario would have a direct effect on privacy risk and disclosure benefit, there are two other mediating factors in between (i.e., first general privacy concern and then trust). It is counter-intuitive that general privacy concerns (which are often considered to be a stable personal trait) could have been influenced by our manipulation of the preference scenario. However, as we measured privacy concern right after the experiment, the presented scenario might have had a lingering effect on participants’ expression of that concern, even though the questions were asked more generically. In particular, our study finds that when people are in a scenario where their preferences do not reflect those of the majority, they perceive significantly higher privacy concerns compared to people whose preferences are aligned with the majority (regardless of whether this means that they are siding with a peer or with a superior). Their increased concerns, in turn, have a negative effect on their trust in the group, which influences their perception of risk and benefit, which may ultimately reduce the amount of information they disclose.

5.1.4 Effect of personality traits on privacy

Our results indicate that extraverts have lower privacy concerns; people with high agreeableness have lower privacy concerns and higher trust; and conscientious people have higher privacy concerns; however, there’s no effect of neuroticism and openness. The findings of the effects of extraversion (Pentina et al. 2016), agreeableness (Anastasi and Urbina 1997; Pentina et al. 2016), and conscientiousness (Pentina et al. 2016) are aligned with previous works, while other findings regarding neuroticism and openness are not. Page et al. (2013) give a potential explanation for the inconsistent effects of personality on privacy concerns: in most research personality serves as a crude proxy for more specific personal characteristics—such as “communication styles”—that have a much closer relationship with privacy concerns. Using more specific personal characteristics remains open for future work.

5.1.5 Effect of agreeableness on trust

Our results indicate that high levels of the agreeableness trait has a positive effect on trust in group and a negative effect on general privacy concern. Agreeableness “involves getting along with others in pleasant, satisfying relationships” (Palmer et al. 2000). Agreeableness emphasizes trust, altruism, compliance and modesty (Anastasi and Urbina 1997). Agreeable individuals are also less likely to judge others’ actions as potentially harmful when faced with privacy threats. Hence, their tendency to trust and to be less suspicious of their environment may reduce their privacy concern. Consequently, they may have lower privacy concerns (Pentina et al. 2016).

5.2 Limitations and future directions

Here, we discuss the limitations of our study and a few promising directions that can advance the design of explanations in the group decision/recommendation context.

5.2.1 Hypothetical personal information

We measured participants’ privacy risk, disclosure benefit, and actual disclosure behavior regarding hypothetical personal information rather than their actual personal information (e.g., their current location, emotion, financial, religion, health, sexuality, and alcohol-related information). The use of hypothetical information allowed us to avoid privacy concerns with the study itself (which could have resulted in a participant selection bias) and the effect of individual differences in the sensitivity of participants actual personal information (e.g., someone with an alcohol addiction will likely find their alcohol-related information more sensitive than someone who does not drink alcohol). A downside of using hypothetical information is that our participants may have been unable to imagine the situation, or that they behaved differently from how they would have behaved if the disclosure scenario presented in the study considered their actual profile. Although we asked them to imagine that the study scenario considered their real information, and participant answers to the open-ended questions show their high engagement in the study, asking participants to share hypothetical personal information still might have led to different results than if the study had considered their actual personal information. Future work could attempt to replicate our findings in real-world group decision-making settings. Additionally, the texts that accompanied the different types of personal information, for example, “financial-related information (i.e., this place is cheap, fits your budget)” were generated in a way that we expected might create privacy concern and would be realistic in a travel scenario. Although this should not have affected our main outcomes which focus on the overall information disclosure and not item-level disclosure, future work should investigate how different descriptive texts for the same information type could lead to different results.

5.2.2 Hypothetical group

A related limitation is that our scenario involved hypothetical group members. To reduce the complexity of the study, each group contained only one active user (participant), who was asked to imagine a specific group based on the specified criteria. To increase the realism of the scenario, we asked participants to enter the real names of the people they imagined to be in this group. We used those particular names throughout the experiment. Future work could study people in real groups to see how group members with different disclosure behaviors interact in a privacy-preserving way to reach a consensus.

5.2.3 Group setting

In this study, we designed three types of preference scenarios as a group setting. The least favorite place of the user was recommended to the group in the minority scenario compared to the two majority scenarios which recommended the favorite place of the user. This allowed us to explore group setting differences to determine if these dimensions affect user information disclosure. However, the active user in this study is never set to be a superior in the group. Future work should investigate more nuanced versions of group settings, i.e., suggesting a place from the middle of the recommendation list or where the active user is set to be a superior in the experiment.

Group size To simplify the design of our experiment, the presented scenario always involved a group of exactly three people. Future work could investigate how group size affects the outcomes of such a study where groups of diverse size are involved in the experiment. The effect of group size is not trivial. For example, a larger group means that any disclosure reveals data to more people, which may increase the potential privacy risk. On the other hand, a larger group also means that more people disclose their personal information, hence one’s own information may be sheltered in the sea of information. Larger groups also have the potential to result in information overload. In that situation, recommending what information is more important to justify one’s opinion becomes more critical, since giving too much information in the justification might cause it to be ignored.

Characteristics of group recommendation systems While this study primarily focuses on group decision-making, we believe that the methodology used in this research could also be applied to different group decision-making situations, including group recommendation systems. However, further investigation is necessary to examine the effects of different characteristics of group recommendation systems on user behavior and decision-making processes. For example, it would be valuable to investigate whether the recommendation strategy or the presentation of recommendation results can enhance users’ information disclosure within the group or increase their acceptance of the recommended items. In future research, we plan to explore these factors to gain a better understanding of how to improve the effectiveness and usability of group recommendation systems.

Group decision-making/recommendation domain The final disclosure decision might be domain-dependent. For example, low involvement and high involvement decision domains (Petty et al. 1983) could be perceived differently in terms of privacy risk and disclosure benefit. For example, in a high-involvement decision domain like the choice of a shared apartment, people might perceive that disclosing personal information has more benefit if it helps to make a better final group decision. At the same time, high-involvement domains may require the disclosure of more sensitive personal information (e.g., in the case of a shared apartment, budget information). The current study was conducted in the context of tourism—a domain that is suitable for studying group decisions, as it is relatable for many participants and commonly involves coordinating with a group of people. As the tourism domain is generally perceived as medium-low involvement (compared to, e.g., shared apartments Felfernig et al. 2017) future work should study the perceived importance of privacy risk and disclosure benefit in domains that have higher levels of involvement and/or risk.

User-tailored privacy for group explanations User-tailored privacy has been proposed and studied as a human-centric solution to reduce users’ privacy concerns using recommender systems (Knijnenburg 2015, 2017). As suggested by advocates of User-Tailored Privacy, it makes it easier to manage one’s privacy by automatically tailoring a system’s privacy settings to the user’s preferences (Knijnenburg 2017). For future work, we plan to utilize the findings of our study to automatically predict a proper balance between users’ desire for privacy and their need for transparency to be able to facilitate group decision making, rather than leaving the decision to decide what information they want to disclose as a recurring burden on the users themselves.

Group modeling In this study, we saw a significant difference between the privacy/disclosure preference of different people (e.g., depending on their personality, or whether their preferences were in the minority or majority). These individual differences may result in situations where the availability of information is asymmetric (e.g., one user wants to hide their location while the other two users disclose it). Future work should leverage existing work on preference aggregation strategies (e.g., Masthoff 2011; Felfernig et al. 2018) to address the challenge of reconciling these differences in privacy/disclosure preferences when generating explanations to the entire group. This work should ultimately lead to the automatic generation of privacy-preserving explanations for group recommendations, adapted to all identified individual and situational factors.

6 Conclusions

In this study, we investigated how groups of people make decisions in the tourism domain. In particular, we developed a web-based chatbot that generates natural language explanations to help group members explain their arguments for or against the places suggested to the group. We presented an online user experiment investigating how users of this chatbot make privacy decisions. The results of this experiment demonstrate the effect of general privacy concerns, personality traits, task design, and preference scenarios on trust, privacy risk and disclosure benefit, and ultimately on personal information disclosure. Importantly, the way the decision task is presented influences how one reasons about privacy risk—this factor has a stronger impact on information disclosure when the task is framed as competitive rather than cooperative. The fact that privacy risk does not play an important role in individuals’ information disclosure decisions when the task is framed as cooperative can be used in group recommendation scenarios to improve information exchange, thereby facilitating the discussion process to reach a consensus in the group.

This study represents a step toward developing explanations for group recommendation/decision systems by taking group members’ privacy concerns into consideration. We have also provided an open-source framework, TouryBot, that we believe will assist the research community in conducting human-centered experiments in a group recommendation/decision context. Our investigation considered different aspects of user disclosure behavior in the group, such as individuals’ personalities. We believe we have provided a robust group decision-making system for future researchers to conduct experiments focusing more on human-centered approaches. Finally, we believe that this study will potentially aid researchers in further exploring many aspects of designing explanations for groups.

Notes

Note our experiment received the ethical committee approval from the Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC) at TU Delft.

As part of this framework, user experience is also included, which represents how users evaluate the system, which is not taken into account in our study.

All material for analyzing our results and replicating our user study, (i.e., user study materials, data gathered in the user study and the analysis scripts) is publicly available—(https://osf.io/z3hnp/?view_only=5db14a9c31ac4592bbdadc98c5bbf7a3).

https://github.com/alejandro-du/vaadin-ai-chat, retrieved March 2021.

An open platform for building web apps in Java (https://vaadin.com/), retrieved September 2021.

https://developer.foursquare.com/, retrieved February 2021.

Previously, we found that privacy concerns are perceived more in loosely-coupled heterogeneous groups than tightly-coupled homogeneous ones (Najafian et al. 2021a). In this work, we therefore, focus on loosely coupled (weak ties) heterogeneous groups to consider privacy concerns in an extreme case.

https://www.prolific.co.

This suggests that people would expect others to reciprocate this behavior. A future study with repeated opportunities for mutual disclosure could investigate whether this influences participants’ behavior in the long run.

References

Anastasi, A., Urbina, S.: Psychological Testing. Prentice Hall/Pearson Education, Hoboken (1997)

Asch, S.E.: Studies of independence and conformity: I. A minority of one against a unanimous majority. Psychol. Monogr. Gen. Appl. 70(9), 1 (1956)

Bansal, G., Gefen, D., et al.: The impact of personal dispositions on information sensitivity, privacy concern and trust in disclosing health information online. Decis. Support Syst. 49(2), 138–150 (2010)

Bansal, G., Zahedi, F.M., Gefen, D.: Do context and personality matter? trust and privacy concerns in disclosing private information online. Inf. Manag. 53(1), 1–21 (2016)

Barile, F., Najafian, S., Draws, T., Inel, O., Rieger, A., Hada, R., Tintarev, N.: Toward benchmarking group explanations: evaluating the effect of aggregation strategies versus explanation (2021)

Caliskan Islam, A., Walsh, J., Greenstadt, R.: Privacy detective: Detecting private information and collective privacy behavior in a large social network. In: Proceedings of the 13th Workshop on Privacy in the Electronic Society, pp. 35–46 (2014)

Cao, D., He, X., Miao, L., An, Y., Yang, C., Hong, R.: Attentive group recommendation. In: The 41st International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research & Development in Information Retrieval, pp. 645–654 (2018)

Chauvin, B., Hermand, D., Mullet, E.: Risk perception and personality facets. Risk Anal. Int. J. 27(1), 171–185 (2007)

Choi, B., Wu, Y., Yu, J., Land, L.P.W.: Love at first sight: the interplay between privacy dispositions and privacy calculus in online social connectivity management. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 19(3), 4 (2018)

Costa, P.T., McCrae, R.R.: Neo personality inventory-revised (NEO PI-R). Psychological Assessment Resources Odessa, FL (1992a)

Costa, P.T., Jr., McCrae, R.R.: Four ways five factors are basic. Personal. Individ. Differ. 13(6), 653–665 (1992b)

Culnan, M.J.: How did they get my name?: An exploratory investigation of consumer attitudes toward secondary information use. MIS Q 17, 341–363 (1993)

Culnan, M.J., Armstrong, P.K.: Information privacy concerns, procedural fairness, and impersonal trust: an empirical investigation. Organ. Sci. 10(1), 104–115 (1999)

Dattalo, P.: Determining Sample Size: Balancing Power, Precision, and Practicality. Oxford University Press, Oxford (2008)

Dinev, T., Bellotto, M., Hart, P., Russo, V., Serra, I., Colautti, C.: Privacy calculus model in e-commerce—a study of Italy and the United States. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 15(4), 389–402 (2006)

Felfernig, A., Atas, M., Tran, T.N.T., Stettinger, M., Erdeniz, S.P., Leitner, G.: An analysis of group recommendation heuristics for high-and low-involvement items. In: International Conference on Industrial, Engineering and Other Applications of Applied Intelligent Systems, pp. 335–344. Springer, Berlin (2017)

Felfernig, A., Boratto, L., Stettinger, M., Tkalčič, M.: Explanations for groups. In: Group Recommender Systems, pp. 105–126. Springer (2018)

Forsyth, D.R.: Group Dynamics. Cengage Learning, Boston (2018)

Havlena, W.J., DeSarbo, W.S.: On the measurement of perceived consumer risk. Decis. Sci. 22(4), 927–939 (1991)

Hofmann, D.A.: Overcoming the obstacles to cross-functional decision making: laying the groundwork for collaborative problem solving. Organ. Dyn. 44(1), 17–25 (2015)

Ioannou, A., Tussyadiah, I., Miller, G.: That’s private! understanding travelers’ privacy concerns and online data disclosure. J. Travel Res. 60, 1510–1526 (2020)

John, O.P., Srivastava, S., et al.: The big five trait taxonomy: history, measurement, and theoretical perspectives. Handb. Personal. Theory Res. 2(1999), 102–138 (1999)

Joinson, A.N., Reips, U.D., Buchanan, T., Schofield, C.B.P.: Privacy, trust, and self-disclosure online. Hum. Comput. Interact. 25(1), 1–24 (2010)

Jozani, M., Ayaburi, E., Ko, M., Choo, K.K.R.: Privacy concerns and benefits of engagement with social media-enabled apps: a privacy calculus perspective. Comput. Hum. Behav. 107, 106260 (2020)

Junglas, I.A., Johnson, N.A., Spitzmüller, C.: Personality traits and concern for privacy: an empirical study in the context of location-based services. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 17(4), 387–402 (2008)

Kehr, F., Kowatsch, T., Wentzel, D., Fleisch, E.: Blissfully ignorant: the effects of general privacy concerns, general institutional trust, and affect in the privacy calculus. Inf. Syst. J. 25(6), 607–635 (2015)

Keith, M.J., Thompson, S.C., Hale, J., Lowry, P.B., Greer, C.: Information disclosure on mobile devices: re-examining privacy calculus with actual user behavior. Int. J. Hum Comput. Stud. 71(12), 1163–1173 (2013)

Kim, D., Park, K., Park, Y., Ahn, J.H.: Willingness to provide personal information: perspective of privacy calculus in IoT services. Comput. Hum. Behav. 92, 273–281 (2019)

Knijnenburg, B.P.: A User-Tailored Approach to Privacy Decision Support. University of California, Irvine (2015)

Knijnenburg, B.P.: Privacy? I can’t even! making a case for user-tailored privacy. IEEE Secur. Priv. 15(4), 62–67 (2017)

Knijnenburg, B.P., Kobsa, A.: Making decisions about privacy: information disclosure in context-aware recommender systems. ACM Trans. Interact. Intell. Syst. (TiiS) 3(3), 1–23 (2013)

Knijnenburg, B.P., Kobsa, A.: Increasing sharing tendency without reducing satisfaction: finding the best privacy-settings user interface for social networks. In: ICIS (2014)

Knijnenburg, B.P., Willemsen, M.C.: Evaluating recommender systems with user experiments. In: Recommender Systems Handbook, pp. 309–352. Springer (2015)

Knijnenburg, B.P., Willemsen, M.C., Gantner, Z., Soncu, H., Newell, C.: Explaining the user experience of recommender systems. User Model. User-Adap. Interact. 22(4–5), 441–504 (2012)

Knijnenburg, B.P., Kobsa, A., Jin, H.: Dimensionality of information disclosure behavior. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 71(12), 1144–1162 (2013)

Kobsa, A., Cho, H., Knijnenburg, B.P.: The effect of personalization provider characteristics on privacy attitudes and behaviors: an elaboration likelihood model approach. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. 67(11), 2587–2606 (2016)

Korzaan, M.L., Boswell, K.T.: The influence of personality traits and information privacy concerns on behavioral intentions. J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 48(4), 15–24 (2008)

Krasnova, H., Spiekermann, S., Koroleva, K., Hildebrand, T.: Online social networks: why we disclose. J. Inf. Technol. 25(2), 109–125 (2010)

Kumar, S., Kumar, P., Bhasker, B.: Interplay between trust, information privacy concerns and behavioural intention of users on online social networks. Behav. Inf. Technol. 37(6), 622–633 (2018)

Kumar, S.P., Saha, S.: Influence of trust and participation in decision making on employee attitudes in Indian public sector undertakings. SAGE Open 7(3), 2158244017733030 (2017)

Kweekel, L., Gerrits, T., Rijnders, M., Brown, P.: The role of trust in CenteringPregnancy: building interpersonal trust relationships in group-based prenatal care in the netherlands. Birth 44(1), 41–47 (2017)

Laufer, R.S., Wolfe, M.: Privacy as a concept and a social issue: a multidimensional developmental theory. J. Soc. Issues 33(3), 22–42 (1977)

Malhotra, N.K., Kim, S.S., Agarwal, J.: Internet users’ information privacy concerns (IUIPC): the construct, the scale, and a causal model. Inf. Syst. Res. 15(4), 336–355 (2004)

Masthoff, J.: Group modeling: Selecting a sequence of television items to suit a group of viewers. In: Personalized digital television, pp. 93–141. Springer (2004)

Masthoff, J.: Group recommender systems: combining individual models. In: Recommender Systems Handbook, pp. 677–702. Springer (2011)

Masthoff, J.: Group recommender systems: aggregation, satisfaction and group attributes. In: Recommender Systems Handbook, pp. 743–776. Springer (2015)