Abstract

Objective

To evaluate efficacy and safety of either or both silodosin and mirabegron as MET for distal ureteric stones ≤ 10 mm.

Patients and methods

This study enrolled a total of 105 patients, aged between 20 and 56 years, diagnosed by single radiopaque distal ureteral stone measuring ≤ 10 mm. The recruitment period spanned from May 2020 to December 2021. The patients were randomly divided into three groups, with each group consisting of 35 participants. Group A received a once-daily dose of 8 mg of silodosin, group B received a once-daily dose of 50 mg of mirabegron, and group C received a combination of both medications. Treatment was administered to all patients until the stone was expelled or for a maximum duration of four weeks. The stone-free rate was determined by analyzing KUB films with or without ultrasonography.

Results

The rate of stone expulsion was significantly higher in group C compared to groups A and B (P = 0.04 and P = 0.004, respectively). The mean (standard deviation) time for stone expulsion in groups A, B, and C was 14 ± 2.3 days, 11 ± 3.1 days, and 7 ± 2.2 days, respectively. Group C demonstrated a significantly shorter stone expulsion time compared to groups A and B (P = 0.001 and P = 0.04, respectively). The frequency of renal colic in group C was significantly lower than that in groups A and B, resulting in a reduced requirement for analgesics (P < 0.05). Anejaculation occurred at a significantly higher rate in the silodosin group (73.9%) and combination group (84%) compared to the mirabegron group (P < 0.05).

Conclusions

The findings of this study suggest that both silodosin and mirabegron are effective treatments for the expulsion of lower ureteric stones. Furthermore, the combination of these medications leads to an increased rate of stone expulsion and a reduced duration of expulsion.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Approximately 20% of urinary stones are located in the ureter, with 70% of them being in the distal ureter. While most stones pass spontaneously, they can cause acute pain (renal colic), creating a need for effective pain relief and improved stone passage methods [1].

The spontaneous expulsion rate of distal ureteric stones is between 25 and 53% for stones ≤ 10 mm in size, making conservative treatment an option for such cases [2]. The spontaneous passage of ureteric stones depends on various factors, including stone size, shape, location, ureteral muscle spasm, ureteral wall edema, and anatomical abnormalities [3].

Medical expulsive therapy (MET) is commonly used to facilitate expulsion of ureteric stones. Alpha-blockers are frequently employed and have been proven effective in clinical practice. Silodosin, a highly selective α1A-adrenoceptor antagonist, has been used as a MET for distal ureteric stones by inducing relaxation of the ureteral muscles and achieving higher stone expulsion rates than other blockers [4].

However, alpha-blockers can have adverse effects due to their mechanism of action, including anejaculation, nausea, dizziness, and orthostatic hypotension. Thus, there is a need for novel, more effective agents with lower complication rates [5].

Beta-3 adrenoceptors (B3AR) are widely present in ureteral smooth muscles, urothelium, and interstitial cells, mediating adrenergic stimulation for ureteral relaxation [6]. Mirabegron, a selective B3AR agonist, has been introduced as a novel MET and offers an effective and safe alternative to previous MET agents that act via different pathways [7].

In this study, we aimed to assess the efficacy and safety of silodosin, mirabegron, or a combination of both as MET for distal ureteric stones ≤ 10 mm.

Patients and methods

This prospective, randomized study was conducted between May 2020 and December 2021. Ethical committee approval was obtained prior to the study. The inclusion criteria consisted of patients over 18 years old with a single radio-opaque stone ≤ 10 mm located in the distal ureter. Exclusion criteria included single functioning kidney, impaired renal function, multiple or bilateral and radiolucent ureteric stones, severe persistent pain, urinary tract infection, severe hydronephrosis (grade IV according to SFU grading system), uncontrolled hypertension, pregnancy, anatomical abnormalities, current use of alpha-blockers, and previous ureteral surgery.

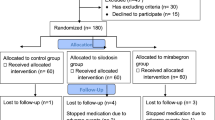

A total of 123 patients with distal ureteric stones were initially assessed for eligibility to participate in the study. Out of these, 18 patients were excluded for various reasons (as shown in Fig. 1). Ultimately, 105 patients who met the inclusion criteria were enrolled in the study. Informed written consent was obtained from all patients after providing them with an explanation of the study procedures and possible side effects of the drugs.

Sample size calculated using G*Power software, the significance level (alpha) α value is 0.05, which corresponds to a 5% chance of making a Type I error (rejecting the null hypothesis when it is true). We Determine the statistical power 1—beta (β). The statistical power is the probability of correctly rejecting the null hypothesis when it is false used value for statistical power is 80%.

The patients were randomly divided into three equal groups using a computer-generated random number table prepared by a statistician who was not part of the research team. Each group consisted of 35 patients. Group A was administered a daily dose of 8 mg of silodosin, Group B received a daily dose of 50 mg of mirabegron, and Group C received a combination of 8 mg of silodosin and 50 mg of mirabegron. The treatment was given to all patients until either the expulsion of the stone occurred or a maximum of 4 weeks had passed.

Patients underwent various assessments, including medical history collection, general examination, blood urea and serum creatinine tests, urine analysis, urine culture, kidney, ureter, and bladder X-ray (KUB), and non-contrast CT. Additionally, patients were advised to take a 30 mg tablet of ketorolac orally during pain attacks, along with the assigned medication. All patients were instructed to consume a minimum of 2500–3000 mL of water daily and strain their urine to detect any potential stones.

Follow-up evaluations were conducted weekly at the outpatient clinic. These evaluations involved collecting information on stone passage, the number of episodes of renal colic, the total amount of extra analgesia required, and any adverse effects associated with the administered drugs. Ultrasonography was also performed during the follow-up visits. The follow-up continued until the stone passed spontaneously or until the treatment was discontinued after 4 weeks. The stone-free rate (SFR), indicating the absence of any stones, was determined using KUB film with or without ultrasonography on a weekly basis. Treatment failure was defined as the persistence of stones confirmed by radiological examination after 4 weeks.

The primary objective of the study was to determine the rate of stone expulsion, while the secondary objectives included assessing the time it took for the stones to be expelled, the number of pain attacks, the amount of additional analgesia required, and the adverse effects associated with the medication. The collected data was reported, reviewed, coded, and entered into the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) version 23. The comparison between the groups was performed using the chi-square test, with a p-value of less than 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Data analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) version 23. Statistical comparisons between groups were conducted using the chi-square test, with P < 0.05 considered significant.

Results

The study included 105 out of 123 patients, and Table 1 presents the demographic and clinical characteristics. There were no statistically significant differences between the groups in patient age, sex, BMI, stone size, laterality, and hydronephrosis degree (P > 0.05), as shown in Table 1. Additionally, there were no statistically significant differences between the groups in terms of pre- or post-treatment serum creatinine levels.

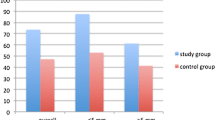

Stone expulsion was reported in 20 out of 35 patients (57.1%) in Group A, 18 out of 35 patients (51.4%) in Group B, and 33 out of 35 patients (94.3%) in Group C. The stone expulsion rate was significantly higher in Group C compared to Groups A and B (P = 0.04 and P = 0.004, respectively). The mean (SD) expulsion time in Groups A, B, and C was 14 ± 2.3 days, 11 ± 3.1 days, and 7 ± 2.2 days, respectively. The stone expulsion time was significantly shorter in the combination group (Group C) compared to the silodosin (Group A) and mirabegron (Group B) groups (P = 0.001 and P = 0.04, respectively).

Regarding renal colic episodes, the combination group (Group C) had a significantly lower frequency in comparison to silodosin (Group A) and mirabegron (Group B) groups, and less analgesic medication was required (P < 0.05), as shown in Table 2. Groups A and C had a higher incidence of headache, dizziness, and orthostatic hypotension compared to Group B. There was a significant difference among the groups regarding the incidence of headache (P < 0.05). Furthermore, the incidence of anejaculation was significantly higher in the silodosin (73.9%) and combination (84%) groups compared to the mirabegron group (P < 0.05), as shown in Table 2.

Discussion

Spontaneous stone expulsion occurs in about 50% of patients, but problems like ureteral colic, UTIs, and hydronephrosis might occur. The use of adjuvant drugs in MET for distal ureteral stones has shown increased stone clearance rates and decreased pain and complications [8].

Highly selective alpha-1A-adrenoceptor blockers, such as silodosin, have emerged as a way to reduce cardiovascular side effects while maintaining effectiveness in the urinary tract. However, these drugs can still cause unwanted effects such as postural hypotension, anejaculation, and dizziness [9].

To address the need for therapeutic agents with different mechanisms of action and fewer side effects, the study explores the use of beta-3 adrenoceptor agonists for ureteral dilation [10].

Real-time quantitative PCR studies have shown that the dilated distal ureter has fewer beta-3 adrenoceptors compared to a healthy part, suggesting the importance of these receptors in ureteral dilation. [11] Based on this data, the study was designed as a prospective, randomized trial to evaluate the efficacy and safety of tamsulosin, mirabegron, or both as MET for distal ureteral stones.

Stone expulsion rate

In this study, we show stone expulsion rates in different treatment groups. In the silodosin group (Group A), stone expulsion was reported in 20 out of 35 patients (57.1%), while in Group B, which received mirabegron, it was observed in 18 out of 35 patients (51.4%). In Group C, which received a combination of both medications, stone expulsion was reported in 33 out of 35 patients (94.3%). The stone expulsion rate was significantly higher in Group C compared to Groups A and B, with P-values of 0.04 and 0.004, respectively. However, there was no statistically significant difference in stone expulsion rates between Group A and Group B, with a P-value of 0.745.

Previous studies have reported stone expulsion rates for silodosin ranging from 66 to 84% for stone sizes less than 10 mm, which is higher than the rates observed with placebo, naftopidil, or tamsulosin [12, 13]. Our finding of a 57.1% stone expulsion rate in the silodosin group for patients with stone sizes between 6 and 9 mm is consistent with the results reported by Itoh et al. [14].

Solakhan et al. conducted a study on patients with distal intramural ureter stones and found that mirabegron resulted in a stone expulsion rate of 73.5%. They observed a significant difference in stone sizes less than 10 mm between the mirabegron group and the control group. However, contrary to our findings, Tang et al. and Solakhan et al. [15, 16] did not find significant effects when combining mirabegron with tamsulosin or diclofenac for stones larger than 5 mm. This divergence in results might be attributed to the use of different drug combinations involving mirabegron in those studies.

Bayar et al. conducted a randomized multicenter research study to evaluate the effectiveness of mirabegron and silodosin in patients with stones ranging from 4 to 10 mm. They reported similar rates of stone expulsion across all groups since they established a control group instead of a combination group, which contrasts with our study [17].

In our current study, Group C, which received combination therapy, exhibited a significantly higher stone expulsion rate of 94.3%. This outcome can be attributed to the administration of two drugs with distinct mechanisms of action.

Stone expulsion time

The average expulsion time (standard deviation) for Groups A, B, and C was 14 ± 2.3 days, 11 ± 3.1 days, and 7 ± 2.2 days, respectively. The combination group (C) had a significantly shorter stone expulsion time compared to the silodosin group (A) and mirabegron group (B) (p = 0.001 and p = 0.04, respectively). Solakhan et al. reported mean stone expulsion times of 7.64 days and 9.2 days for the mirabegron group in distal ureteric stone in different studies. Consistent with our findings, some trials reported stone expulsion times ranging from 10.27 to 14.8 days in the silodosin group for distal ureteric stones [13, 14, 18]. However, other studies reported shorter expulsion times, ranging from 8.09 to 9.4 days [19, 20].

The numbers of renal colic episodes and the need for analgesics.

Ureteric colic occurs when there is increased pressure within the ureter proximal to the site of obstruction. Alpha-adrenergic receptor (AR) antagonists block the C fibers responsible for mediating ureteric colic [21].

Several in vivo studies in animals have demonstrated the relaxant effect of beta-3 agonists on the ureter, leading to a significant decrease in intraluminal pressure. Mirabegron, a beta-3 agonist, relaxes ureteric musculature and dilates the ureteral lumen by stimulating beta-3 adrenoreceptors. This mechanism of action makes mirabegron a potentially effective and safe alternative for medical expulsive therapy (MET), which operates through different pathways [22].

The mirabegron group (B) had a lower frequency of renal colic episodes in comparison to the silodosin group (A) (0.8 ± 0.06 vs. 1.6 ± 1.1, p = 0.001). The combination group (C) had an even lower frequency (0.6 ± 0.2), and fewer analgesics were required (P = 0.001) Recent clinical trials have identified a notable distinction between the mirabegron group and control groups regarding the occurrence of renal colic episodes and the requirement for analgesics in patients with distal ureter stones [15, 17]. Kumar et al. documented an average of 0.8 pain episodes in the silodosin group [18].Substantial evidence suggests that the administration of mirabegron, in combination with other alpha-adrenoreceptor antagonists, for the treatment of distally located ureteral stones is associated with improved stone-free rates (SFR), reduced stone expulsion intervals, and fewer colic attacks [23,24,25,26].

Adverse effects

In our study, no serious adverse effects were observed because both drugs are safe and well tolerated. Anejaculation occurred in 17 out of 23 patients (73.9%) in group A and 21 out of 25 patients (84%) in group C, but no patient discontinued the treatment. The condition was reversible and resolved quickly after stopping the treatment.

Blood pressure and pulse rate did not significantly alter in our study patients. Our findings are supported by a review of the literature, which reveals that a 50 mg dose of mirabegron is not connected to changes in blood pressure or heart rate [27].

Silodosin, which is a highly selective α1A-AR blocker, demonstrates a better stone expulsion rate (57.1%) compared to mirabegron (51.4%). However, mirabegron has the advantage of reducing the stone expulsion time (11 ± 3 vs. 14 ± 2.3 days), numbers of renal colic, and the analgesia requirements. It also has a favorable safety profile with low complications. Therefore, mirabegron shows promise as a medical expulsive therapy (MET) agent for patients with distal ureteric stones.

When silodosin and mirabegron are combined, there is an even higher stone-free rate (94.3%), shorter expulsion times (7 ± 2.2 days), and a reduction in episodes of renal colic (0.6 ± 0.2). This combination therapy offers the advantage of fewer colicky episodes as well. Therefore, for distal ureteric stones with a diameter of ≤ 10 mm, it is recommended to consider the addition of silodosin as a therapy, and mirabegron can be administered to help reduce numbers of renal colic and the analgesia requirements.

Limitations of the study

The limitations of our study are that non-contrast CT was not done in the follow-up period to assess the stone-free rate due to financial necessity. Silodosin is a labeled medication for lower ureteric stone, but mirabegron is not yet labeled for the treatment of lower ureteric stone. Increases the cost of treatment due to the combination of drugs. Additionally, the small sample size and single-center work suggest the need for larger studies to be conducted.

Conclusions

The current study concluded that silodosin and mirabegron are effective therapies for the expulsion of lower ureteric stones, Overall, the combination of therapies for lower ureteric stones offers increased stone expulsion rates, shorter expulsion times, better pain control, and a favorable safety profile. This approach represents an effective and comprehensive strategy for managing lower ureteric stones and improving patient outcomes. without any serious adverse effects. Additional research involving a large sample size and multiple centers is necessary.

References

Ahmed AF, Al-Sayed AY (2010) Tamsulosin versus alfuzosin in the treatment of patients with distal ureteral stones: prospective, randomized, comparative study. Korean J Urol 51:193–197

Pearle MS, Lotan Y (2012) Urinary lithiasis: etiology, epidemiology, and pathogenesis. In: Wein AJ, Kavoussi LR, Novick AC, Partin AW, Peters CA (eds) Campbell-Walsh urology, 10th edn. Saunders Elsevier, Philadelphia, pp 1257–1286

Tao RZ, Qin ZQ, Liu FD, Lv JL (2019) Efficacy and safety of tamsulosin in the medical expulsion therapy for distal ureteral calculi: a systematic review and meta-analysis of placebo-controlled trials. Urol J 16(3):224–231

Sur RL, Shore N, L’Esperance J, Knudsen B, Gupta M, Olsen S et al (2015) Silodosin to facilitate passage of ureteral stones: a multi institutional, randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial. Eur Urol 67:959–964

De Coninck V, Antonelli J, Chew B, Patterson JM, Skolarikos A, Bultitude M (2019) Medical expulsive therapy for urinary stones: future trends and knowledge gaps. Eur Urol 76(5):658–666

Urkmez A, Tokuc E, Topaktas R, Sahin A, Yuksel OH (2019) Mirabegron: a novel and promising medical expulsive treatment for ureteral stones? J Coll Physicians Surg Pak 29(1):73–74

Solakhan M, Bayrak O, Bulut E (2019) Efficacy of mirabegron in medical expulsive therapy. Urolithiasis 47(3):303–307

Dellabella M, Milanese G, Muzzonigro G (2005) Randomized trial of the efficacy of tamsulosin, nifedipine and phloroglucinol in medical expulsive therapy for distal ureteral calculi. J Urol 174:167–72

Tzortzis V, Mamoulakis C, Rioja J, Gravas S, Michel MC, dela Rosette JJ (2009) Medical expulsive therapy for distal ureteral stones. Drugs 69:677–92

Beach MA, Mauro LS (2006) Pharmacologic expulsive treatment of ureter al calculi. Ann Pharmacother 40:1361–1368

Saki S, Daichi I, Mana K et al (2017) β- and β-adrenergic receptor stimulation differ in their effects on PGC-1α and atrogin-1/ MAFbx gene expression in chick skeletal muscle. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol 211:1–6

Tsuzaka Y, Matsushima H, Kaneko T, Yamaguchi T, Homma Y (2011) Naftopidil vs silodosin in medical expulsive therapy for ureteral stones: a randomized controlled study in Japanese male patients. Int J Urol 18:792–795

Gupta S, Lodh B, Singh AK, Somarendra K, Meitei KS, Singh SR (2013) Comparing the efcacy of tamsulosin and silodosin in the medical expulsion therapy for ureteral calculi. J Clin Diagn Res 7:1672–1674

Itoh Y, Okada A, Yasui T, Hamamoto S, Hirose M, Kojima Y (2011) Efficacy of selective á1A adrenoceptor antagonist silodosin in the medical expulsive therapy for ureteral stones. Int J Urol 18:672–674

Solakhan M, Bayrak O, Bulut E (2019) Efficacy of mirabegron in medical expulsive therapy. Urolithiasis 47(3):303–307

Tang QL, Wang DJ, Zhou S, Tao RZ (2021) Mirabegron in medical Expulsive therapy for distal ureteral stones: a prospective, randomized, controlled study. World J Urol 39(12):4465–4470

Bayar G, Yavuz A, Cakmak S, Ofluoglu Y, Kilinc MF, Kucuk E et al (2020) Efficacy of silodosin or mirabegron in medical expulsive therapy for ureteral stones: a prospective, randomized controlled study. Int Urol Nephrol 52(5):835–840

Kumar S, Jayant K, Agrawal MM, Singh SK, Agrawal S, Parmar KM (2015) Role of tamsulosin, tadalafl, and silodosin as the medical expulsive therapy in lower ureteric stone: a randomized trial (a pilot study). Urology 85:59–63

Sentürk AB, Aydin C, Ekici M, Yaytokgil M, Akkoc A, Baykam MM (2018) Comparison of three most frequently used alpha blocker agents in medical expulsive therapy for distal ureteral calculi, result of a retrospective observational study. Arch Ital Urol Androl 31(90):25–28

Gharib T, Mohey A, Fathi A, Alhefnawy M, Alazaby H, Eldakhakhny A (2018) Comparative study between silodosin and tamsulosin in expectant therapy of distal ureteral stones. Urol Int 101:161–166

Kinnman E, Nygards EB, Hansson P (1997) Peripheral alpha-adrenoreceptors are involved in the development of capsaicin induced ongoing and stimulus evoked pain in humans. Pain 69:79–85

Wanajo I, Tomiyama Y, Yamazaki Y, Kojima M (2011) Ureteral selectivity of intravenous beta-adrenoceptor agonists in pig model of acute ureteral obstruction: comparison of KUL-7211, a selective beta2/beta3 agonist, with isoproterenol, terbutaline, and CL-316243. Urology 77:e1-6

Dellabella M, Milanese G, Muzzonigro G (2003) Efficacy of tamsulosin in the medical management of juxtavesical ureteral stones. J Urol 170(6 pt 1):2202–2205. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ju.0000096050.22281.a7

Hollingsworth JM, Rogers MA, Kaufman SR, Bradford TJ, Saint S, Wei JT et al (2006) Medical therapy to facilitate urinary stone passage: a meta-analysis. Lancet 368(9542):1171–1179. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69474-9

Singh A, Alter HJ, Littlepage A (2007) A systematic review of medical therapy to facilitate passage of ureteral calculi. Ann Emerg Med 50(5):552–563. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2007.05.015

Beach MA, Mauro LS (2006) Pharmacologic expulsive treatment of ureter al calculi. Ann Pharmacother 40:1361–1368

Michel MC, Gravas S (2016) Safety and tolerability of β3 -adrenoceptor agonists in the treatment of overactive bladder syndrome–insight from transcriptosome and experimental studies. Expert Opin Drug Saf 15(5):647–657. https://doi.org/10.1517/14740338.2016.1160055

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AS Mohammad: Project development, data collection, manuscript writing and revision. SM Ahmed: Data collection and analysis. A Mostafa: Data collection and revision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

There is no conflict of interest.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from all patients after explaining all possible outcomes and complications. Ethical Committee registration number is SVU, MED, URO01642211494).

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Abdel-Kader, M.S., Sayed, A.M., Sayed, S.M. et al. Evaluation of the efficacy and safety of either or both mirabegron and silodosin, as a medical expulsive therapy for distal ureteric stones. Int Urol Nephrol 56, 1605–1610 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11255-023-03880-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11255-023-03880-y