Abstract

Purpose

Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) sequelae in the transplant population are scarcely reported. Post-COVID-19 mucormycosis is one of such sequelae, which is a dreadful and rare entity. The purpose of this report was to study the full spectrum of this dual infection in kidney transplant recipients (KTR).

Methods

We did a comprehensive analysis of 11 mucormycosis cases in KTR who recovered from COVID-19 in IKDRC, Ahmedabad, Gujarat, India during the study period from Nov 2020 to May 2021. We also looked for the risk factors for mucormycosis with a historical cohort of 157 KTR who did not develop mucormycosis.

Results

The median age (interquartile range, range) of the cohort was 42 (33.5–50, 26–60) years with 54.5% diabetes. COVID-19 severity ranged from mild (n = 10) to severe cases (n = 1). The duration from COVID-19 recovery to presentation was 7 (7–7, 4–14) days. Ten cases were Rhino-orbital-cerebral-mucormycosis (ROCM) and one had pulmonary mucormycosis. Functional endoscopic sinus surgery (FESS) was performed in all cases of ROCM. The duration of antifungal therapy was 28 (24–30, 21–62) days. The mortality rate reported was 27%. The risk factors for post-transplant mucormycosis were diabetes (18% vs 54.5%; p-value = 0.01), lymphopenia [12 (10–18) vs 20 (12–26) %; p-value = 0.15] and a higher neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio [7 (4.6–8.3) vs 3.85 (3.3–5.8); p-value = 0.5].

Conclusion

The morbidity and mortality with post-COVID-19 mucormycosis are high. Post-transplant patients with diabetes are more prone to this dual infection. Preparedness and early identification is the key to improve the outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV2) has drastically impacted all the domains of humanity and solid-organ transplant recipient (SOT) is not a mere exception. However, there are enough evidence-based data to bolster the increased vulnerability of SOT with SARS-CoV2 compared to the general [1,2,3] and waitlisted patients [4, 5]. This fact ranks them at the top of the priority list for the medical community. There have been a lot of speculations about the imminent threat to COVID-19 survivors even after discharge. There are a few reports of follow-up studies in the general population, but the data are limited pertaining to SOT. Mucormycosis is one such infection that has emerged as post-COVID-19 sequelae. It is regarded as an opportunistic infection before the pandemic but recently has been recognized in increasing numbers with COVID-19. The causation and association between these two are incompletely understood. As SOT is already a proven risk factor for mucormycosis [6, 7], this problem statement expands in the COVID-19 era. There is a growing need to understand the clinical spectra and management of this deadly combination to improve the outcomes in SOT, as the data are scarce. The authors have previously reported two cases of post-COVID-19 mucormycosis in kidney transplant recipients (KTR) which are included in this study as well [8]. To date, there are only a few cases reports in SOT [9, 10] who acquired post-COVID-19 mucormycosis. To the best of our knowledge, this remains the largest case series of post-COVID-19 mucormycosis in KTR which could sever a learning tool for transplant physicians across the globe.

Methodology

Ethical statement

This was a retrospective study organized in a single center after getting an ethical approval letter from the institution (Registration number: ECRJ143/InstlGJ/2013/RR-19 with application number EC/App/20Jan21/07). The study was reported as per the Strengthening The Reporting of OBservational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) checklist. We followed the norms of the Transplantation of Human Organs and Tissues Act (THOTA), India; the declaration of Helsinki, and the declaration of Istanbul. The patient’s privacy and confidentiality were maintained throughout the process of the study.

Design, settings, and study population

The study was conducted at the department of nephrology and transplantation, IKDRC-ITS, Ahmedabad, Gujarat, India. All KTR with COVID-19 confirmed by SARS-CoV2 real-time polymerase chain test (RT-PCR) through nasopharyngeal swab or positive SARS-CoV2 spike protein antibody test by chemiluminescence immunoassay were included during the study period from May 2020 to May 2021. COVID-19 was defined as mild (signs of upper respiratory tract/no oxygen requirement), moderate (signs of pneumonia without the need of supplemental oxygen), and severe (severe pneumonia with oxygen saturation below 90% on room air) [11]. The cases were managed as per the availability of resources and drugs and as per the national guidelines for the management of COVID-19 [12]. The details of the 11 KTR who developed mucormycosis after COVID-19 infection were described in the study. The diagnosis of mucormycosis was confirmed by histopathological examination, KOH mount, and culture.

Institutional immunosuppression protocols

The immunosuppression protocol for COVID-19 in the center involved stopping of antimetabolite for 7 days in mild cases and gradual reintroduction after improvement of symptoms. In cases of moderate to severe COVID-19, both antimetabolite and calcineurin inhibitors (CNI) were stopped for 7 days and were insidiously restored depending on the clinical convalescence. There was no change in drug regimen for asymptomatic cases. The immune modulation in post-COVID-19 mucormycosis involved stopping antimetabolite and giving minimum doses of CNI in stable cases. In cases, with altered sensorium, or oxygen requirements only steroids in minimum doses were resumed. Antimetabolite was reintroduced after 2–3 weeks, and CNI was restored only after clinical recovery from mucormycosis. The immunosuppression changes were personalized depending on the clinical response and physician’s discretion and we were not strict with our baseline protocol.

The treatment regimen for mucormycosis

A dedicated room for managing mucormycosis was arranged in the hospital. The multidisciplinary team composed of nephrologists, transplant physicians, ophthalmologists, and ENT specialists was formed for managing this difficult-to-treat infection. Due to resource limitations, radiological imaging tests such as magnetic resonance imaging Para nasal sinus (MRI-PNS) or computed tomography (CT PNS) with or without contrast were performed in a different nearby imaging laboratory. Antifungal therapy was majorly composed of liposomal amphotericin B that was started with an initial dose of 1 mg/kg and gradually increased to 3–5 mg/kg after monitoring for any side effects. Posaconazole (n = 3) was less used due to limited availability and affordability. The planned duration of antifungal therapy was 21–28 days and beyond as per the clinical response. Functional endoscopic sinus surgery (FESS) was planned and performed as feasible and as early as possible.

Data collection and analysis

Demographic and clinical data which encompass a detailed evaluation of the cases were collected by the two authors (RD and HSM) and analyzed further. Laboratory parameters were retrieved from the hospital’s electronic software. The data were expressed as frequencies, percentages for categorical variables, and median interquartile range (IQR), and range for continuous variables. The comparison between historical cohort [13] which was reported recently and mucormycosis was done by Fisher test, Chi-square with Yates’s correction, or t test as appropriate. A two-tailed p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analysis was done using SPSS software 17 version.

Results

In the COVID-19 pandemic, we report a total of 11 post-COVID-19 mucormycosis cases were identified among KTR after COVID-19. One KTR and three liver transplant recipients with ROCM from the second wave were excluded due to incomplete details.

Demographic characteristics of the cohort

Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of the cohort. The median (IQR, range) of the cohort was 42 (33.5–50, 26–60) years with males (n = 10) accounting for the bulk of cases. The gap period from the time of transplant surgery to acquiring COVID-19 was 5 (2–7.5, 2–17) years. The body mass index was 25 (23–31.5, 19–32) kg/m2, and Charlson’s co-morbidity index was 3 (2.5–3.5, 2–6) of the cohort. The blood group distribution for the study included A (n = 4), B (n = 4), and O (n = 3). Only 1 case was a deceased donor, the rest others were living-related transplants. Diabetes as a co-morbidity was seen in 6 of the 11 cases. In only 2 cases, there was a history of uncontrolled blood sugars. Thymoglobulin (n = 8) was the predominant induction used in the study. The majority of the cohort was on triple immunosuppression (n = 8). The median tacrolimus level was 4.9 (4.45–5.15) ng/ml. There was no occupational hazard for mucormycosis. In addition, there was no history of recent trauma or antirejection therapy given. None of the cases was immunized with the SARS-CoV2 vaccine.

COVID-19 course of the cohort before admission for mucormycosis

Table 2 exhibits the detailed clinical details during the COVID-19 admission of the cohort. Three cases were managed on an out-patient basis for the COVID-19, while others were hospitalized. Only 1 case was managed in the intensive care unit. The most common clinical manifestations during COVID-19 included fever (n = 11), and cough (n = 10). Anxiety (n = 4) and depression (n = 4) were also present in many cases. The oxygen requirement of the cohort during COVID-19 admission included home-based care (n = 3), no oxygen therapy (n = 5) and low flow oxygen (n = 2), and high flow oxygen (n = 1). No case was on mechanical ventilation. Radiological abnormalities were detected in all the cases. The laboratory derangement during COVID-19 included higher neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio [7 (4.6–8.3, 3.3–11.2)], lower lymphocyte percentage [12 (10–18, 8–25) %], higher interleukin-6 levels [94.2 (66–108, 21–114) pg/ml], higher high sensitivity C-reactive protein [44 (38–128, 7.2–238) mg/dl], high D-dimer [1013 (497–1359, 174–2070) ng/ml] and serum ferritin levels [523 (423–1000, 248–1280) ng/ml]. Most of the cases were treated with a combination of steroids, anticoagulation and remdesivir (n = 7). The majority of the cases were treated with remdesivir, steroids and anticoagulation. The dose of steroids was 6 mg OD dexamethasone for 10 days in the three cases which required oxygen therapy. None of the cases received prophylactic antibiotics or antifungals during the COVID-19 stay. The immunosuppression management for COVID-19 is detailed in methodology. No patient had allograft dysfunction or any other complaints at discharge.

Clinical features and management of post-COVID-19 mucormycosis in kidney transplant recipients

The time gap between discharge from COVID-19 to the onset of symptoms of mucormycosis was 7 (7–7, 4–14) days. The clinical signs and symptoms (Table 3) described in decreasing order of frequency included facial swelling (n = 10), headache (n = 10), proptosis (n = 10), nasal crusting (n = 10), orbital cellulitis (n = 8), chemosis (n = 6), paresthesia (n = 4), ophthalmoplegia (n = 4), difficulty in vision (n = 3), epistaxis (n = 3), foul-smelling or black discharge from nose or throat (n = 3), toothache (n = 3), vision loss (n = 2), palate crusting (n = 2), fever (n = 1) and sings of pneumonia (n = 1). Most cases were classified as ROCM (n = 7), and only a few had cerebral involvement (n = 3) or pulmonary (n = 1). No cutaneous, disseminated or gastrointestinal tract mucormycosis cases were reported. The confirmatory diagnosis of mucormycosis was made by KOH and HPE + biopsy in all of the cases. The culture was not isolated in any of the cases. The management involved immunosuppression drug regimen alteration which is detailed in the methodology. The antifungal therapy used was liposomal amphotericin B (n = 11) and Posaconazole (n = 3). FESS was performed in all of the ROCM cases. The cumulative median dose of Liposomal amphotericin B received was 280 (240–400) mg/kg for 28 (24–40, 21–62) days of treatment.

The outcome of post-COVID-19 mucormycosis in kidney transplant recipients

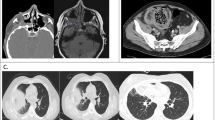

Three deaths were reported in the study which corresponds to a mortality rate of 27%. In only one case (Case 1), where orbital exenteration was needed, the patient died after battling a morbid clinical course of around 2 months from the onset of COVID-19 symptoms. The pulmonary mucormycosis (Case 2) presented with ground-glass opacity initially which progressed to right lung cavitary pneumonia. He was diagnosed with mucormycosis from bronchoscopy and biopsy. Lung excision was planned but the patient perished before surgery. The only case, which was on high flow oxygen during COVID-19 (Case 3), developed ROCM with brain involvement after 7 days of COVID-19 discharge. He died even after a timely functional endoscopic sinus surgery. The entire cohort was SARS-CoV2 RT-PCR negative during the entire hospital stay. Acute kidney injury was reported in 6 (54.4%) of the cases. All three patients with mortality required hemodialysis sessions, while it was not needed in any of the survivors. The median serum creatinine value at baseline, peak value during COVID-19, and just before the diagnosis of mucormycosis was 1.3 (1.2–1.6), 1.5 (1.25–2.1), and 1.6 (1.3–2.2) mg/dl, respectively. The peak serum creatinine during mucormycosis treatment and last follow-up were 2.1 (1.67–2.65) mg/dl and 1.35 (1.27–1.95) mg/dl, respectively. All alive cases (n = 8) achieved graft recovery (two had partial and six had complete recovery).

Comparison of COVID-19 course of the historical cohort who had not developed post-COVID-19 mucormycosis

The findings of our cohort were compared with a historical cohort of 157 KTR, in which mucormycosis was not reported (Table 4). Among the comorbidities, the presence of diabetes was associated with post-COVID-19 mucormycosis (18% vs 54.5%; p-value = 0.01). Obesity was also higher but not statistically significant (24% vs 45.5%; p-value = 0.15). Among the clinical symptoms fever (58% vs 100%; p-value = 0.003) and cough (49% vs 90%; p-value = 0.009) were reported higher in post-COVID-19 mucormycosis compared to the historical cohort. There were other differences described below which were statistically not significant. Mild cases (73% vs 43%; p-value = 0.1) were higher and there were fewer cases (20% vs 9%; p-value = 0.69) with severe COVID-19 in post-COVID-19 mucormycosis. Among the laboratory profile, lymphopenia [12 (10–18) vs 20 (12–26); p-value = 0.15] and higher neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio [7 (4.6–8.3) vs 3.85 (3.3 -5.8); p-value = 0.5] was more associated with post-COVID-19 mucormycosis.

Discussion

There is an extensive literature in the context of clinical profile and outcome of COVID-19 in SOT [14] including kidney [15,16,17], liver [18], lung [19], and heart [20, 21]. Transplantation activity ceased around the world during the COVID-19 peak, but it is estimated that postponing transplantation will result in excess of deaths [22] and hence depending on the COVID-19 surge and available resources, the transplantation should be resumed. There are also upcoming reports of usage of lesser potent induction and immunosuppression regimen in the COVID-19 era [23], the future implications of which in is unknown.

Need for follow-up studies in transplantation

There are various reports of follow-up studies of COVID-19 in the general population, but there are limited such reports in SOT [24, 25]. The follow-up studies have shown COVID-19 survivors to be at increased risk of adverse events [26, 27]. There have been concerning reports of readmissions and the risk of heightened clinical deterioration after discharge in COVID-19 [28,29,30]. In a recent report, comorbidities like diabetes are shown to be more prone to adverse events post-discharge [31, 32]. We report, our experience of readmissions for post-COVID-19 mucormycosis in KTR from India.

Factors for the increased burden of mucormycosis in COVID-19

In a meta-analysis of 101 cases of mucormycosis associated with COVID-19 in general patients, high numbers (n = 82) are constituted from India [33]. The exact culprit for this explosion of mucormycosis is difficult to pinpoint. A confluence of factors may be operating and are postulated for this dual infection such as overuse of steroids, uncontrolled sugars, prolonged hospital stay, and overzealous use of antibiotics, reuse of face mask, steam inhalation, zinc and iron supplementation [34, 35]. In our cohort, all the cases had a history of mask reuse, while multivitamins such as zinc and iron were used in 4 cases, along with steam inhalation in two cases. In addition, SARS-CoV2 in itself can cause immune dysregulation and provide fertile soil for the growth of invasive fungal infections [36, 37]. We have performed an extensive comparison of KTR with COVID-19 who acquired mucormycosis compared to the cohort who did not. We found blood markers such as lymphopenia and high NLR cases to be more prone to post-COVID-19 mucormycosis. Since the advent of the pandemic, these two factors have been associated with poor prognosis and mortality in COVID-19 [38]. In addition, lymphopenia per se is an important risk factor for invasive fungal infection [39]. Another important finding is the higher proportion of diabetics and younger age compared to pre-pandemic cases. This highlights the further vulnerability of KTR for mucormycosis during the pandemic.

We also had a comparison of the outcome of mucormycosis cases in pre-pandemic times with post-COVID-19 mucormycosis. Our institute is one of the high-volume transplant centers in India, which has previously reported two to three cases of post-kidney transplant mucormycosis yearly in the pre-COVID-19 era [40]. The incidence of post-COVID-19 mucormycosis has staggeringly increased in our center compared to the pre-COVID-19 era. From 2015 to 2019, 14 cases of non-COVID-19 mucormycosis were identified in our center. Of the 14 cases, 8 (57%) patient was classified as ROCM, 5 (36%) with pulmonary mucormycosis and 1 (7%) with disseminated mucormycosis. Only 3 (21%) of the 14 cases were diabetic. The mean age of the cases was 54.7 years. One graft loss (7%) and three (21%) mortality were reported. Thus, post-COVID-19 mucormycosis in the current report are younger (44 vs 54.7) years, more frequently diabetic (54% vs 21%), and ROCM (91% vs 57%) compared to non-COVID-19 mucormycosis. In addition, the mortality reported was slightly higher in post-COVID-19 mucormycosis (27% vs 21%).

A comparison of mucormycosis in KTR with the general population

The majority of our study had ROCM which is similar to the general population. In our report, CT scans and MRI demonstrated evidence of mucosal thickening of sinuses, orbital and intracranial involvement with maxillary and ethmoidal sinus being the most affected, which simulates the reports from the general population. Diabetes was exclusively reported in a meta-analysis of 41 general patients [41]. Our report also had half of the cases with diabetes. The reports in the general patients had severe COVID-19 and which is dissimilar to our report as the majority had either mild or moderate illness, and only one case was on oxygen therapy in our report. This observation highlights the fact that SOT is more prone to this invasive infection compared to the general masses owing to a pre-existing chronic immunocompromised state. The mortality reported in previous reports in general patients is quite high, which emphasizes the importance of early treatment which could have relatively improved the outcome in our study of post-COVID-19 mucormycosis in SOT. Another significant concern is the graft outcome in this group of patients, where continued treatment with nephrotoxic drugs like Amphotericin B along with attenuation of maintenance IS can result in poor graft outcomes. However, in our report, only two cases had partial recovery, which was expected as IS tailoring is unavoidable in such cases. On an encouraging note, we observed that with gradual introduction and escalation of immunosuppression, creatinine level reached baseline in most cases. Thus, a favorable graft outcome was reported in the study, which is mainly attributed to maintaining a balance between immunosuppression and infection during treatment.

How to manage post-COVID-19 mucormycosis?

Immunosuppression alteration is challenging and there is no fixed consensus in such complex cases. A personalized and low threshold for decreasing drugs was our approach which was quite successful in our report. Antifungal therapy should be started before confirmation of diagnosis even in clinically suspected cases, as early initiation of antifungal therapy is one of the most important factors responsible for survival [42]. Antifungal treatment alone is ineffective in all mucormycosis cases as there is vascular thrombosis and ischemic necrosis of tissues which prevents effective entry of antifungal drugs. Therefore, radical debridement of infected and necrotic tissue of sinuses should be performed as early as possible to improve the outcomes [35]. All of our patients underwent FESS within an average of 5 days from admission. The pulmonary mucormycosis reported in our case series succumbed before surgery, and it shows the difficulty in isolating and managing such cases. There would be many undiagnosed cases of invasive fungal infections as bronchoscopy and BAL was not done due to resource limitations in many such cases, and were treated with empirical antifungal therapies. Transplant patients with COVID-19 must have a preliminary eye, nose, oral, and cranial nerve examination for any signs such as eschar, black nasal or oral discharge, eye swelling, or cranial nerve palsy [43]. After discharge, these patients should be informed about the risk and instructed to look for any signs at home.

Future implications

Further research in transplant settings will help in better delineating the pathogenesis and spectrum of post-COVID-19 sequelae. Eradication of COVID-19 through vaccination or drug therapy seems far at this point. Moreover, there are reports of decreased efficacy [44] and breakthrough COVID-19 after vaccination in SOT [45, 46]. Hence, COVID-19 is still a constant menace for SOT and they should undertake adequate precautions to safeguard themselves. SOT and transplant physicians should be aware of any possibility of sequelae following COVID-19 discharge.

Conclusion

The occurrence of mucormycosis has dramatically increased in COVID-19-recovered transplant patients. This poses additional morbidity and mortality in the follow-up of COVID-19. The strict control of blood sugars, judicious use of steroids, and balancing immunosuppression medications is essential to decrease the incidence and burden. Increased awareness on the part of the patient and physician is invariably warranted for early diagnosis and management. Prompt medical therapy along with surgical intervention is the mainstay for improving survival.

Data availability

Data will be available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Hadi YB, Naqvi SFZ, Kupec JT, Sofka S, Sarwari A (2021) Outcomes of COVID-19 in solid organ transplant recipients: a propensity-matched analysis of a large research network. Transplantation 105(6):1365–1371

Fisher AM, Schlauch D, Mulloy M et al (2021) Outcomes of COVID-19 in hospitalized solid organ transplant recipients compared to a matched cohort of non-transplant patients at a national healthcare system in the United States. Clin Transplant 35(4):e14216

Caillard S, Chavarot N, Francois H et al (2021) Is COVID-19 infection more severe in kidney transplant recipients? Am J Transplant 21(3):1295–1303

Santos CAQ, Rhee Y, Hollinger EF et al (2021) Comparative incidence and outcomes of COVID-19 in kidney or kidney-pancreas transplant recipients versus kidney or kidney-pancreas waitlisted patients: a single-center study. Clin Transplant 98:187

Mohamed IH, Chowdary PB, Shetty S et al (2021) Outcomes of renal transplant recipients with SARS-CoV-2 infection in the eye of the storm: a comparative study with waitlisted patients. Transplantation 105(1):115–120

Serris A, Danion F, Lanternier F (2019) Disease entities in mucormycosis. J Fungi (Basel) 5(1):23

Roden MM, Zaoutis TE, Buchanan WL et al (2005) Epidemiology and outcome of zygomycosis: a review of 929 reported cases. Clin Infect Dis 41(5):634–653

Meshram HS, Kute VB, Chauhan S, Desai S (2021) Mucormycosis in post-COVID-19 renal transplant patients: a lethal complication in follow-up. Transpl Infect Dis. https://doi.org/10.1111/tid.13663

Arana C, Cuevas Ramírez RE, Xipell M et al (2021) Mucormycosis associated with covid19 in two kidney transplant patients. Transpl Infect Dis. https://doi.org/10.1111/tid.13652

Khatri A, Chang KM, Berlinrut I, Wallach F (2021) Mucormycosis after coronavirus disease 2019 infection in a heart transplant recipient—case report and review of the literature. J Mycol Med 31(2):101125

Gandhi RT, Lynch JB, Del Rio C (2020) Mild or moderate covid-19. N Engl J Med 383(18):1757–1766

Clinical Management Protocol: COVID-19 Government of India Ministry of Health and Family Welfare Directorate General of Health Services (EMR Division) Version 3 13.06.20. Available from: https://www.mohfw.gov.in/pdf/ClinicalManagementProtocolforCOVID19.pdf. Accessed 05 June 2021

Kute VB, Meshram HS, Patel HV et al (2021) Clinical profiles and outcomes of COVID-19 in kidney transplant recipients: experience from a high-volume public sector transplant center in India. Exp Clin Transplant 19(9):899–909. https://doi.org/10.6002/ect.2021.0188

Danziger-Isakov L, Blumberg EA, Manuel O, Sester M (2021) Impact of COVID-19 in solid organ transplant recipients. Am J Transpl 21(3):925–937

Al-Otaibi TM, Gheith OA, Abuelmagd MM et al (2021) Better outcome of COVID-19 positive kidney transplant recipients during the unremitting stage with optimized anticoagulation and immunosuppression. Clin Transpl. https://doi.org/10.1111/ctr.14297

Kute VB, Bhalla AK, Guleria S et al (2021) Clinical profile and outcome of COVID-19 in 250 kidney transplant recipients: a multicenter cohort study from India. Transplantation 105(4):851–860

Meshram HS, Kute VB, Patel H et al (2021) Feasibility and safety of remdesivir in SARS-CoV2 infected renal transplant recipients: a retrospective cohort from a developing nation. Transpl Infect Dis. https://doi.org/10.1111/tid.13629

Jayant K, Reccia I, Virdis F et al (2021) COVID-19 in hospitalized liver transplant recipients: An early systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Transpl 35(4):e14246

Saez-Giménez B, Berastegui C, Barrecheguren M et al (2021) COVID-19 in lung transplant recipients: a multicenter study. Am J Transpl 21(5):1816–1824

Patel SR, Gjelaj C, Fletcher R et al (2021) COVID-19 in heart transplant recipients-A seroprevalence survey. Clin Transpl. https://doi.org/10.1111/ctr.14329

de Miranda Soriano RV, Rossi Neto JM, Finger MA, Dos Santos CC, Lin-Wang HT (2021) COVID-19 in heart transplant patients: case reports from Brazil. Clin Transpl. https://doi.org/10.1111/ctr.14330

Peters TG, Bragg-Gresham JL, Klopstock AC et al (2021) Estimated impact of novel coronavirus-19 and transplant center inactivity on end-stage renal disease-related patient mortality in the United States. Clin Transpl. https://doi.org/10.1111/ctr.14292

Sandal S, Boyarsky BJ, Massie A, Chiang TP, Segev DL, Cantarovich M (2021) Immunosuppression practices during the COVID-19 pandemic: a multinational survey study of transplant programs. Clin Transpl. https://doi.org/10.1111/ctr.14376

Chauhan S, Meshram HS, Kute V, Patel H, Desai S, Dave R (2021) Long-term follow-up of SARS-CoV-2 recovered renal transplant recipients: a single-center experience from India. Transpl Infect Dis. https://doi.org/10.1111/tid.13735

Bajpai D, Deb S, Bose S et al (2021) Recovery of kidney function after AKI because of COVID-19 in kidney transplant recipients. Transpl Int 34(6):1074–1082. https://doi.org/10.1111/tri.13886

Xiong Q, Xu M, Li J et al (2021) Clinical sequelae of COVID-19 survivors in Wuhan, China: a single-centre longitudinal study. Clin Microbiol Infect 27(1):89–95

Huang C, Huang L, Wang Y et al (2021) 6-month consequences of COVID-19 in patients discharged from hospital: a cohort study. Lancet 397(10270):220–232

Donnelly JP, Wang XQ, Iwashyna TJ, Prescott HC (2021) Readmission and death after initial hospital discharge among patients with COVID-19 in a large multihospital system. JAMA 325(3):304–306

Yeo I, Baek S, Kim J et al (2021) Assessment of thirty-day readmission rate, timing, causes and predictors after hospitalization with COVID-19. J Intern Med. https://doi.org/10.1111/joim.13241

Ye S, Hiura G, Fleck E et al (2021) Hospital readmissions after implementation of a discharge care program for patients with COVID-19 illness. J Gen Intern Med 36(3):722–729

Lavery AM, Preston LE, Ko JY et al (2020) Characteristics of hospitalized COVID-19 Patients discharged and experiencing same-hospital readmission, United States, March-August 2020. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 69(45):1695–1699

Bowles KH, McDonald M, Barrón Y, Kennedy E, O’Connor M, Mikkelsen M (2021) Surviving COVID-19 after hospital discharge: symptom, functional, and adverse outcomes of home health recipients. Ann Intern Med 174(3):316–325

Singh AK, Singh R, Joshi SR, Misra A (2021) Mucormycosis in COVID-19: a systematic review of cases reported worldwide and in India. Diabetes Metab Syndr. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsx.2021.05.019

Patel A, Agarwal R, Rudramurthy SM et al (2021) Multicenter epidemiologic study of coronavirus disease-associated mucormycosis. India Emerg Infect Dis 27(9):2349–2359. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2709.210934

Sen M, Honavar SG, Bansal R et al (2021) Epidemiology, clinical profile, management, and outcome of COVID-19-associated rhino-orbital-cerebral mucormycosis in 2826 patients in India—collaborative OPAI-IJO study on mucormycosis in COVID-19 (COSMIC), report 1. Indian J Ophthalmol 69(7):1670–1692. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijo.IJO_1565_21

van de Veerdonk FL, Brüggemann RJM, Vos S et al (2021) COVID-19-associated Aspergillus tracheobronchitis: the interplay between viral tropism, host defense, and fungal invasion. Lancet Respir Med. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00138-7

Toor SM, Saleh R, Sasidharan Nair V, Taha RZ, Elkord E (2021) T-cell responses and therapies against SARS-CoV-2 infection. Immunology 162(1):30–43

Imran MM, Ahmad U, Usman U, Ali M, Shaukat A, Gul N (2021) Neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio-A marker of COVID-19 pneumonia severity. Int J Clin Pract 75(4):e13698. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcp.13698

Kontoyiannis DP, Wessel VC, Bodey GP, Rolston KV (2000) Zygomycosis in the 1990s in a tertiary-care cancer center. Clin Infect Dis 30(6):851–856

Godara SM, Kute VB, Goplani KR et al (2011) Mucormycosis in renal transplant recipients: predictors and outcome. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl 22(4):751–756

John TM, Jacob CN, Kontoyiannis DP (2021) When uncontrolled diabetes mellitus and severe COVID-19 converge: the perfect storm for mucormycosis. J Fungi (Basel) 7(4):298

Song Y, Qiao J, Giovanni G, Liu G, Yang H, Wu J, Chen J (2017) Mucormycosis in renal transplant recipients: review of 174 reported cases. BMC Infect Dis 17(1):283

Cornely OA, Alastruey-Izquierdo A, Arenz D, Chen SC, Dannaoui E, Hochhegger B, Hoenigl M, Jensen HE, Lagrou K, Lewis RE, Mellinghoff SC (2019) Global guideline for the diagnosis and management of mucormycosis: an initiative of the European confederation of medical mycology in cooperation with the mycoses study group education and research consortium. Lancet Infect Dis 19(12):e405–e421

Boyarsky BJ, Werbel WA, Avery RK et al (2021) Antibody response to 2-dose SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine series in solid organ transplant recipients. JAMA 325(21):2204–2206

Meshram HS, Kute VB, Shah N et al (2021) Letter to editor: COVID-19 in kidney transplant recipients vaccinated with Oxford-AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine (Covishield): a single center experience from India. Transplantation. https://doi.org/10.1097/TP.0000000000003835

Caillard S, Chavarot N, Bertrand D et al (2021) Occurrence of severe COVID-19 in vaccinated transplant patients. Kidney Int. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2021.05.011

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All the authors have made an equal contribution to the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

None.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Meshram, H.S., Kute, V.B., Chauhan, S. et al. Mucormycosis as SARS-CoV2 sequelae in kidney transplant recipients: a single-center experience from India. Int Urol Nephrol 54, 1693–1703 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11255-021-03057-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11255-021-03057-5