Abstract

Introduction

Robotic assisted radical prostatectomy (RARP) is gaining widespread acceptance for the management of localized prostate cancer. However, data regarding patient expectations and satisfaction outcomes after RARP are scarce.

Methods

We developed a structured program for preoperative education and evidence-based counseling using a multi-disciplinary team approach and measured its impact on patient satisfaction in a cohort of 377 consecutive patients who underwent RARP at our institution. Responses regarding overall, sexual, and continence satisfaction were assessed.

Results

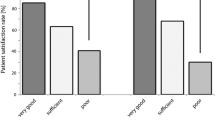

Fifty percent of our patient cohort replied to the questionnaire assessments. Ninety-three percent of responding patients expressed overall satisfaction after RARP with only 0.5% expressing regret at having had the operation. Biochemical recurrence and lack of continence correlated significantly with low levels of satisfaction, though sexual function was not significantly different among those satisfied and those not. Most patients (97%) valued oncologic outcome as their top priority, with regaining of urinary control being the commonest second priority (60%).

Conclusions

RARP appears to be associated with a high degree of patient satisfaction in a cohort of patients subjected to a structured preoperative education and counseling program. Oncologic outcomes are most important to these patients and have the largest influence on satisfaction scores.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Jemal A, Thomas A, Murray T, Thun M (2002) Cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin 52(1):23–47

Derweesh IH, Kupelian PA, Zippe C, Levin HS, Brainard J, Magi-Galluzzi C et al (2004) Continuing trends in pathological stage migration in radical prostatectomy specimens. Urol Oncol 22(4):300–306

Sakr WA, Haas GP, Cassin BF, Pontes JE, Crissman JD (1993) The frequency of carcinoma and intraepithelial neoplasia of the prostate in young male patients. J Urol 150(2 Pt 1):379–385

Klotz L (2010) Active surveillance for prostate cancer: a review. Curr Urol Rep 11(3):165–171

Clark JA, Wray NP, Ashton CM (2001) Living with treatment decisions: regrets and quality of life among men treated for metastatic prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol 19(1):72–80

Schroeck FR, Krupski TL, Sun L, Albala DM, Price MM, Polascik TJ et al (2008) Satisfaction and regret after open retropubic or robot-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy. Eur Urol 54(4):785–793

Hart SL, Latini DM, Cowan JE, Carroll PR (2008) Fear of recurrence, treatment satisfaction, and quality of life after radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer. Support Care Cancer 16(2):161–169

Wei JT, Dunn RL, Litwin MS, Sandler HM, Sanda MG (2000) Development and validation of the expanded prostate cancer index composite (EPIC) for comprehensive assessment of health-related quality of life in men with prostate cancer. Urology 56(6):899–905

Eastham JA, Scardino PT, Kattan MW (2008) Predicting an optimal outcome after radical prostatectomy: the trifecta nomogram. J Urol 179(6):2207–2210 discussion 10-1

Rosen RC, Riley A, Wagner G, Osterloh IH, Kirkpatrick J, Mishra A (1997) The international index of erectile function (IIEF): a multidimensional scale for assessment of erectile dysfunction. Urology 49(6):822–830

Han M, Partin AW, Zahurak M, Piantadosi S, Epstein JI, Walsh PC (2003) Biochemical (prostate specific antigen) recurrence probability following radical prostatectomy for clinically localized prostate cancer. J Urol 169(2):517–523

D’Amico AV, Whittington R, Malkowicz SB, Weinstein M, Tomaszewski JE, Schultz D et al (2001) Predicting prostate specific antigen outcome preoperatively in the prostate specific antigen era. J Urol 166(6):2185–2188

Henderson A, Andreyev HJ, Stephens R, Dearnaley D (2006) Patient and physician reporting of symptoms and health-related quality of life in trials of treatment for early prostate cancer: considerations for future studies. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 18(10):735–743

Clark JA, Talcott JA (2006) Confidence and uncertainty long after initial treatment for early prostate cancer: survivors’ views of cancer control and the treatment decisions they made. J Clin Oncol 24(27):4457–4463

Mishel MH, Germino BB, Lin L, Pruthi RS, Wallen EM, Crandell J et al (2009) Managing uncertainty about treatment decision making in early stage prostate cancer: a randomized clinical trial. Patient Educ Couns 77(3):349–359

Tewari AK, Srivastava A, Mudaliar K, Tan GY, Grover S, El Douaihy Y et al (2010) Anatomical retro-apical technique of synchronous (posterior and anterior) urethral transection: a novel approach for ameliorating apical margin positivity during robotic radical prostatectomy. BJU Int. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09318.x

Tewari A, Jhaveri J, Rao S, Yadav R, Bartsch G, Te A et al (2008) Total reconstruction of the vesico-urethral junction. BJU Int 101(7):871–877

Herr HW (1997) Quality of life in prostate cancer patients. CA Cancer J Clin 47(4):207–217

Hu JC, Nelson RA, Wilson TG, Kawachi MH, Ramin SA, Lau C et al (2006) Perioperative complications of laparoscopic and robotic assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy. J Urol 175(2):541–546 discussion 6

Fischer B, Engel N, Fehr JL, John H (2008) Complications of robotic assisted radical prostatectomy. World J Urol 26(6):595–602

Badani KK, Kaul S, Menon M (2007) Evolution of robotic radical prostatectomy: assessment after 2,766 procedures. Cancer 110(9):1951–1958

Murphy DG, Kerger M, Crowe H, Peters JS, Costello AJ (2009) Operative details and oncological and functional outcome of robotic-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy: 400 cases with a minimum of 12 months follow-up. Eur Urol 55(6):1358–1366

Kim V, Spandorfer J (2001) Epidemiology of venous thromboembolic disease. Emerg Med Clin North Am 19(4):839–859

Soens MA, Birnbach DJ, Ranasinghe JS, van Zundert A (2008) Obstetric anesthesia for the obese and morbidly obese patient: an ounce of prevention is worth more than a pound of treatment. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 52(1):6–19

Wolin KY, Luly J, Sutcliffe S, Andriole GL, Kibel AS (2009) Risk of urinary incontinence following prostatectomy: the role of physical activity and obesity. J Urol 183(2):629–633

Geary ES, Dendinger TE, Freiha FS, Stamey TA (1995) Nerve sparing radical prostatectomy: a different view. J Urol 154(1):145–149

Catalona WJ, Basler JW (1993) Return of erections and urinary continence following nerve sparing radical retropubic prostatectomy. J Urol 150(3):905–907

Karakiewicz PI, Tanguay S, Kattan MW, Elhilali MM, Aprikian AG (2004) Erectile and urinary dysfunction after radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer in Quebec: a population-based study of 2,415 men. Eur Urol 46(2):188–194

Wagner L, Faix A, Cuzin B, Droupy S (2009) Sexual dysfunction after radical prostatectomy. Prog Urol 19(Suppl 4):S168–S172

Takenaka A, Leung RA, Fujisawa M, Tewari AK (2006) Anatomy of autonomic nerve component in the male pelvis: the new concept from a perspective for robotic nerve sparing radical prostatectomy. World J Urol 24(2):136–143

Haber GP, Aron M, Ukimura O, Gill IS (2008) Energy-free nerve-sparing laparoscopic radical prostatectomy: the bulldog technique. BJU Int 102(11):1766–1769

Stolzenburg JU, Do M, Rabenalt R, Pfeiffer H, Horn L, Truss MC et al (2003) Endoscopic extraperitoneal radical prostatectomy: initial experience after 70 procedures. J Urol 169(6):2066–2071

Menon M, Shrivastava A, Kaul S, Badani KK, Fumo M, Bhandari M et al (2007) Vattikuti Institute prostatectomy: contemporary technique and analysis of results. Eur Urol 51(3):648–657 discussion 57–8

Vickers AJ, Bianco FJ, Serio AM, Eastham JA, Schrag D, Klein EA et al (2007) The surgical learning curve for prostate cancer control after radical prostatectomy. J Natl Cancer Inst 99(15):1171–1177

Vickers AJ (2008) Editorial comment on: impact of surgical volume on the rate of lymph node metastases in patients undergoing radical prostatectomy and extended pelvic lymph node dissection for clinically localized prostate cancer. Eur Urol 54(4):802–803

Tewari A, Rao S, Martinez-Salamanca JI, Leung R, Ramanathan R, Mandhani A et al (2008) Cancer control and the preservation of neurovascular tissue: how to meet competing goals during robotic radical prostatectomy. BJU Int 101(8):1013–1018

Acknowledgments

No external funding was obtained for this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1: Patients education protocol

We follow a structured preoperative education and counseling program. This program involves two preoperative sessions with nurses, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, fellows, surgeons, or surgical coordinators. In the first session, patients undergo multi-step counseling comprising a thorough explanation about the disease, as well as discussion of different treatment modalities and their possible outcomes. The second session focuses on preoperative, perioperative, and postoperative surgical issues. An effort is made to match clinical outcomes discussion with the patient’s unique demographic, oncological and medical data. For example, we highlight that obese patients can have a more challenging recovery and higher grades, and stages of cancer can negatively impact longer-term functional recovery.

Preoperative preparations

The preoperative issues include discontinuation of known and potential blood thinners, weight loss, an exercise protocol, as well as preoperative medical and cardiac consults in appropriate patients. High-risk patients are also encouraged to meet the anesthesiologist preoperatively. A list of possible complications such as bleeding, fever, port site hernias, bowel injury, urinary leakage, pain expectations, cardiac and thrombogenic complications are mentioned, and measures to minimize these events such as exercise and weight loss are also discussed [19–22]. Patients with a BMI >30 are counseled for their greater risk of anesthesia-related, perioperative, and surgical complications. This includes thrombo-embolic disease, anesthesia side-effects, incontinence, and sexual dysfunction following surgery [23–25]. We therefore institute a weight loss program for these patients and monitor them regularly. Once adequate progress is noted, a surgical date is finalized. Non-compliant patients are either referred to a weight loss specialist for more intensive programs or even recommended alternative treatments such as radiation ± hormonal therapy.

Postoperative expectations

Physical activity expectations

We highlight the value of ambulation following surgery. Patients who are sedentary prior to surgery are encouraged to follow a cardio and resistance training program following clearance from their internist. We motivate patients to start walking on their first postoperative day. They continue on a walking program of 2–3 miles/day for the first 6–12 weeks, and are encouraged to continue moderate exercise, other co-morbidities permitting, in the long term. We ask patients to refrain from strenuous exercise so as to protect the port site sutures. We also warn against cycling in the early postoperative period as this can be painful. Patients are given written materials regarding the above issues.

Return to work expectations

Our own data suggests that the average time to return to work is around 17 days. Naturally, the suggested resting time before return to work depends on the type of job. Desk jobs require less time (circa 2 weeks) than jobs that require strenuous physical activity (circa 3–4 weeks). We advise that return to work should be gradual with rests in the afternoon and no heavy lifting.

Pain expectations

Preoperatively, patients are told that pain might be experienced during the first postoperative week; it usually peaks in the first 24–48 h and declines thereafter. Our own data suggests that by the end of the first postoperative week, pain is usually limited to the incision sites and managed with non-steroidals. Narcotic use is very rarely required. The other common source of pain is the laparoscopy-related insufflations which usually peaks on postoperative days 2–3 and gets better once the patient starts passing flatus. Mobilization usually helps in expulsion of flatus and is encouraged. The catheter can be a source of penile pain and is managed by intraurethral lidocaine 2%. Upon catheter removal acute urinary retention can rarely occur, and patients are warned to inform the team and head immediately to the nearest emergency room if it does happen.

Cancer control expectations

We discuss our own series’ outcomes regarding margin rates and PSA recurrence. We highlight their individual risk of extraprostatic extension (EPE), contralateral involvement, and PSMs. We also warn patients with higher Gleason grades that their functional outcomes might be compromised in an attempt to afford them the best chance of cure. We tell patients that oncologic outcomes are program-dependent and always counsel based on our own results. We also discuss adjuvant and salvage therapy in the event of EPE, PSM, or biochemical recurrence. We also have a discussion about the possibility of lymph nodal positivity and the management options if that should occur. High-risk patients with Gleasons 8–10, clinical T3 disease, and multiple positive biopsy cores are counseled about the need for adjuvant therapies, and consults with the medical oncologist and the radiation therapist are set up preoperatively.

Expectations of return of urinary continence

Urinary incontinence has a significant negative impact on most patients’ QOL. We tell patients that immediately after the catheter is removed, they will usually experience some degree of leakage, although in most cases this is relatively mild. However, the vast majority of patients become continent with time in our series. The small percent that remain incontinent are counseled about Kegel exercises, biofeedback, sling procedures, and artificial urinary sphincters.

We provide the patients with our own results such that they go into the surgery with realistic expectations [17]. High-risk scenarios for incontinence or delayed continence include high BMI, large prostatic volume, non-nerve-sparing surgery, short urethral stump, previous urethral/prostatic surgery, and any idiopathic or neurologic condition affecting bladder storage.

Expectations of sexual function recovery

This is one of the most sensitive (for the patient) and challenging (for both surgeon and patient) aspect of prostate cancer surgery. Recovery of the sexual function following RARP depends on a vast list of oncologic [26], demographic [27, 28], medical, social [29], technical [30–33], and surgical experience [34, 35] related factors. Since most of the published data reports best case scenarios, patients often have very high expectations for sexual recovery [6]. This often becomes a source of lasting regret. We thus spend a lot of our preoperative education and counseling time discussing this aspect of the trifecta and use our own results to explain likely recovery times based on individual patient risk factors.

We highlight challenges of nerve preservation in the context of competing goals for nerve-sparing and complete eradication of cancer [36]. We use anatomic diagrams and cartoons to supplement patients’ understanding. MRI images and biopsy maps are generated to further aid the discussions. We ensure that by the end of our structured education and counseling program prospective surgical candidates have a clear idea of the extent and rationale for the proposed nerve sparing.

Appendix 2: Patient questionnaire

-

1.

Please rank the following in order of your PRE-OPERATIVE priorities for treatment: (1= most important, 3= least important). Each number may be used only once.

-

Preservation of sexual function

-

Post operative urinary continence (no urine leakage)

-

Oncologic clearance (cancer-free)

-

-

2.

Considering your current level of urine control ONLY, how satisfied are you with your decision to have had robotic surgery (select one)?

-

Regret having operation (0)

-

Extremely dissatisfied (1)

-

Dissatisfied (2)

-

Neutral (3)

-

Satisfied (4)

-

Extremely satisfied (5)

-

-

3.

Considering your current level of sexual function ONLY, how satisfied are you with your decision to have had robotic surgery (select one)?

-

Regret having operation (0)

-

Extremely dissatisfied (1)

-

Dissatisfied (2)

-

Neutral (3)

-

Satisfied (4)

-

Extremely satisfied (5)

-

-

4.

Overall, how satisfied are you with the treatment you received for your prostate cancer (select one)?

-

Regret having operation (0)

-

Extremely dissatisfied (1)

-

Dissatisfied (2)

-

Neutral (3)

-

Satisfied (4)

-

Extremely satisfied (5)

-

-

5.

Given your treatment experience, would you recommend robotic surgery to your friends/family (select one)?

—Yes—No

-

6.

If you would not recommend robotic surgery, please place an “X” on the line next to the SINGLE most influential factor in your dissatisfaction (a,b) and the specific reason (i–iii) if any.

-

a.

Unrealized expectations of robotic surgery—

-

b.

Poor clinical care (hospital staff, operating rooms, outpatient, etc.)—

-

i.

Disappointing postoperative functional outcomes, specifically urine control or return of sexual function—

-

ii.

Disappointing cancer control (i.e. biochemical recurrence)—

-

iii.

Greater than expected degree of pain or time away from work—

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Douaihy, Y.E., Sooriakumaran, P., Agarwal, M. et al. A cohort study investigating patient expectations and satisfaction outcomes in men undergoing robotic assisted radical prostatectomy. Int Urol Nephrol 43, 405–415 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11255-010-9817-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11255-010-9817-5