Abstract

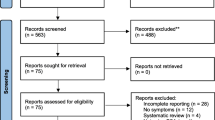

Patients with elevated and/or rising prostate-specific antigen (PSA), minor lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS), and no evidence for prostate cancer on (multiple) extended prostate biopsies are a regularly encountered problem in urological practice. Even now, patients are seen with no objective explanation of this persistent elevated and/or rising PSA. So far, many strategic proposals have been elaborated and published to deal with this specific population including the use of different PSA derivates; applying different biopsy schemes—strategies—biopsy target imaging; diagnostic use of prostate cancer genes; and many more. In this review, we propose a new algorithm in which an urodynamic evaluation should be included since bladder outlet obstruction (BOO) can be expected. Once BOO is confirmed, a transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) can be offered to these patients. This procedure will result in subjective and biochemical improvement and allows extensive histological examination. Current literature was reviewed with regard to this specific population. This research was performed using the commercially available Medline online search tools and applying the following search terms: “diagnostic TURP”; “elevated PSA”; and “prostate biopsy”. Furthermore, subsequent reference search was executed on retrieved articles.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Twenty-five percent of men over 50 years old have lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS). LUTS may be caused by benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), one of the most common diseases among ageing men and the second most common cause of surgery in men over 60 years old [1]. Another condition that might be accompanying LUTS could be prostate cancer (PCa), which has become the most common cancer in men in several developed countries, especially in Western populations and particularly among the black population of the United States.

Since the concept of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) has been introduced in clinical practice [2], many patients are referred to an urologist because of elevated and/or rising PSA levels. To find the cause of these elevated and/or rising PSA levels, often extended prostate biopsies are taken. If cancer cells are discovered in the biopsies, therapy is usually straightforward. If, however, prostate biopsies are negative for cancer cells, numberless diagnostic strategies have been put forward. When PSA levels remain high or rise even more, new extended prostate biopsies are usually taken, eventually with different methods. When PSA levels keep on rising and when extended prostate biopsies remain negative in this group of patients, uncertainty will grow for patients, as well as for general practitioners and last but not least for urologists. More specifically, this will be the case if the patient suffers only minor LUTS. We have previously shown that this group of patients (patients with elevated/and or rising PSA levels, minor LUTS and no signs of prostate cancer) are likely to have bladder outlet obstruction (BOO) on pressure flowmetry according to Abram–Griffiths definition [3, 4]. Despite minor to no LUTS, transurethral resection of prostate (TURP) is a therapeutic option that can be offered to patients resulting in (super)normalisation of PSA levels, symptomatic benefit, and improvement of the quality of life. Additionally, this technique allows extended histological examination, which will reveal in few cases prostate cancer that can be aggressive and need further treatment. Since patients with elevated and/or rising PSA, minor LUTS, and (multiple) negative extended prostate biopsies can be expected to have BOO, we elaborated a new algorithm in which we propose to consider urodynamic evaluation as well as the possibility of performing a TURP in this group of patients.

What are urologists doing today with patients presenting with elevated and/or rising PSA levels, minor LUTS, and no signs of prostate cancer on (multiple) extended prostate biopsies?

Strategies related to PSA evaluation

If PSA is elevated and/or rising in a patient with minor LUTS, no signs of prostate cancer on digital rectal examination and/or transrectal ultrasound (TRUS), and eventually on extended prostate biopsies, different PSA derivates have been proposed. A first PSA derivative that can be used is age-related PSA levels [5]. However, the use of age-specific PSA cut-off values can result in missing up to 60% of cancers in men older than 60 years of age [6]. Borer concluded that age-specific PSA references did not safely eliminate the need for prostate biopsies in a population aged 60–79 years [7].

A second PSA derivate that is regularly used is PSA density. When a cut-off value of 0.078 is used for PSA density, the sensitivity for detection of prostate cancer is 95% [5]. Especially in intermediate PSA levels, PSA density nomograms allow a more precise determination than age-related PSA levels [8].

A third very frequently used PSA derivative, which is related to PSA kinetics, is PSA velocity. Despite its frequent use, caution is required as different methods exist to calculate PSA velocity [9]. The best way to calculate PSA velocity is by performing linear regression. However, in routine practice urologists often use the rate of PSA change using the first and last value. The arithmetic equation of PSA change should not be recommended [9]. Carter [10] proposed a cut-off value of 0.75 ng ml−1year−1 for PSA velocity. Since the use of this cut-off value has been shown to result in missing 48% of prostate cancers, Loeb [11] advised in men younger than 60 years to use a cut-off value of 0.4 ng ml−1year−1. Additionally, Berger [12] showed that PSA velocity increases in the years before diagnosis of prostate cancer, which correlates well with the pathological stage and with Gleason scores.

Another PSA derivate that can be used is the PSA ratio. The use of this parameter with a cut-off value of 25% results in sensitivity of 95% in prostate cancer diagnosis [5]. Catalona [13] proved that the use of PSA ratio can reduce the number of unnecessarily performed biopsies in men with elevated PSA levels on the condition that cut-off values are well defined. An additional PSA-derived parameter was investigated by Froehner who evaluated the value of complexed PSA in comparison with total PSA [14]. Using this parameter, a statistical advantage was detected. However, clinical relevance remains unclear.

Several authors investigated the use of “benign” PSA [15–18]. BPSA is a “benign” form of free PSA that seems to be increased in patients with BPH. A correlation was found with transition zone volume and total prostate volume. However, as is the case with some other PSA derivatives, more studies are needed to confirm its clinical utility.

In addition to these PSA-derived parameters, molecular assays are a new tool that can be used to refine difficulties in PSA interpretation. A well-described and commercially available molecular assay is the PCA3 assay [19]. PCA3 is a very prostate cancer-specific gene also called DD3. When a cut-off value of 35 is used, sensitivity amounted 58–65% with a specificity of 66–72% (PSA specificity of 47%) [19–21]. Haese and colleagues [22] conducted a prospective, multicentre study including 463 patients with one or two negative biopsies who were scheduled for a repeat biopsy. Aim of the study was to compare the diagnostic accuracy of PCA3 with fPSA%. With a cut-off value of 35 for PCA3, the probability of a positive repeat biopsy was greater if PCA3 was higher. Deras et al. [23] found PCA3 to be independent of prostate volume, serum PSA, and number of previous biopsies. Although these assays are promising, there are some disadvantages related to these tests. First of all, it should be emphasised that they cannot be used in a routine screening as they are far more expensive. Secondly, these tests can also give false-negative and false-positive results. Therefore, more evidence confirming the use and the outcome of these assays is required. Last but not least, in addition to these molecular assays, common extended prostate biopsies are still needed to prove possible prostate cancer.

Strategies related to technique and prostate biopsy regimen

Numerous publications have been made on techniques of prostate biopsies. Hodge [24] started with ultrasound guided, 6-core random biopsies. Subsequently, Eskew [25] proved 5-region prostate biopsies to be superior to sextant biopsies, resulting in an increasing diagnostic yield. A few years later, a 10-core protocol with laterally directed biopsies together with sextant biopsies was developed by Gore [26]. Arnold [27] extended the biopsy technique to a 12-core regimen. This extension resulted in a 13.5% increased detection rate of prostate cancer in comparison with sextant biopsies combined with transition zone biopsies [28]. Additional techniques were developed by Matsumoto [29], who described a technique where special attention was taken for deep apical biopsies and Lui [30], who advised on more specific attention for transition zone biopsies. However, other authors have shown that biopsies of transition zone and seminal vesicles resulted in low additional yield in the diagnosis of prostate cancer [31–33]. Recently, Guichard [34] proposed a 21-core biopsy protocol. Compared to sextant biopsies, a 22% improvement in prostate cancer detection rate was observed with a 12-core biopsy. When using a 21-core protocol, the cancer detection rate was further increased to 42.5% compared to 38.7% with 12-core biopsies. Scattoni et al. [35] reviewed the literature on extended and saturation prostate biopsies and concluded extended biopsies should be performed at first biopsy, saturation biopsies at repeated biopsies. However, Ashley [36] evaluated the diagnostic yield of saturation biopsies. In these latter biopsy protocols, 24 or more biopsy cores are taken. Ultimately, they proved that saturation biopsies did not detect more abnormal pathology than standard biopsies [36].

Although prostate biopsies are a standard technique, one has to be aware of the possible complications of this procedure, which are excellently reviewed by Raaijmakers [37]. Minor complications such as haematuria, hemospermia, etc. are frequently seen. Severe complications occur less frequently: fever (3.5%), acute urinary retention (0.4%), and hospitalisation (0.5%).

Another dilemma with prostate biopsies is how many repeat biopsies should be taken. Djavan [38, 39] investigated the cancer detection rate in repeat biopsies. He observed that prostate cancer detection rate in a first biopsy was 24%. In a second biopsy, the cancer detection rate lowered to 13%. Prostate cancers found in first and second biopsies were comparable in terms of PSA, grade, stage, and cancer volume. Cancer detection rate in biopsies three and four were far less, 5 and 4% respectively.

What to do if extended prostate biopsies remain negative and PSA keeps on rising?

In case prostate biopsies remain negative and PSA keeps on rising at the same time, many urologists treat these patients with antibiotics. However, several authors noticed that inflammation seems to have no effect on PSA [40–42], putting the antibiotic treatment in question. Another frequently used strategy is an attempt to normalise PSA with dietary manipulation [43–45]. However, these data do not support the hypothesis that dietary manipulation protects against prostate cancer. For example, Eastham [46] showed that fat intake was not associated with PSA levels. Therefore, advocating functional foods or supplements explicitly for cancer control purposes would currently be premature.

What has been suggested so far to deal with those patients?

Several authors [47–50] showed that PSA can be seen as a marker for BOO, as a predictor of future prostate growth and as a marker for risk of acute urinary retention in patients with LUTS. Furthermore, a correlation was found with an elevated need for surgical treatment of BPH in symptomatic patients [50].

However, the challenging problem are patients with elevated and/or rising PSA, minor LUTS, normal digital rectal examination (DRE) and/or TRUS, and (multiple) negative extended prostate biopsies. This problem is well recognised in literature [51, 52].

A first attempt to deal with this problem was described by Rovner [53]. He showed that a transurethral sampling of at least four quadrant chips together with prostate biopsies in patients with elevated and/or rising PSA levels and negative prostate biopsies did not significantly improve prostate cancer diagnosis. Kitamura [54] evaluated 139 consecutive patients with negative prostate biopsies. These patients received TURP for relief of LUTS implying that these patients were symptomatic. Because four of these patients were revealed to have prostate cancer during the follow-up period, the authors concluded that the role of TURP in these patients remained unclear. Zigeuner [55] performed a retrospective analysis in patients with LUTS. All patients had (multiple) negative extended prostate biopsies. Another important characteristic in this group of patients was that besides an elevated PSA level, 21.8% of these patients had an abnormal DRE. After TURP, prostate cancer was detected in 7.9% of all cases and in 5.5% of the patients with a normal DRE. Zigeuner [55] concluded that detection rate was low and that diagnostic yield in asymptomatic men remained unknown.

Özden [56] evaluated 64 patients with LUTS and normal DRE presenting with elevated PSA levels and negative extended prostate biopsies. When TURP was performed, BPH was encountered in 63 patients, and in 1 patient prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia was detected. Six months after TURP, 7 of 64 patients still had an elevated PSA level. In 3 of these 7 patients, prostatitis was suggested to be the reason of PSA elevation; 1 patient seemed to have prostate cancer; and the remaining 3 patients were diagnosed having BPH. The long-term follow-up in these 7 patients was unclear.

Radhakrishnan [57] described a retrospective analysis in 14 patients undergoing TURP after at least two negative extended prostate biopsies. In 21% of the subjects, aggressive prostate cancer was encountered. In 50% of the subjects, PSA values returned to normal after TURP. In 1 patient, repeated prostate biopsies revealed prostate cancer after TURP. Philip [58] presented results in 11 patients with prostate cancer diagnosed in TURP after negative extended prostate biopsies with 24–48 cores. Out of these 11 patients, 5 patients underwent a radical retropubic prostatectomy in which organ-confined cancer was found, especially located anteriorly. Additionally, in this group of patients TURP was performed to resolve LUTS. Important to notice in this group of patients is that prostate cancer was mainly located anteriorly.

Puppo [59] described the role of TURP together with biopsies of the peripheral zone in the same session in the diagnosis of prostate cancer after repeated negative biopsies. In this study, a group of 43 patients with at least two negative extended prostate biopsies is described. In 35 of the 43 patients, further PSA elevation was shown and these patients underwent new prostate biopsies. In 7 of 35 patients, prostate cancer was shown after repeated prostate biopsies. Additionally, 3 patients were lost during the follow-up period and 4 patients had a severe co-morbidity and hence were unable to undergo TURP. The remaining 21 patients were offered TURP together with prostate biopsies of the peripheral zone regardless of BOO. In this group of 21 patients, 14 patients accepted to undergo TURP. In 8 of these 14 patients, prostate cancer was diagnosed and these patients underwent a radical prostatectomy. The remaining 6 patients had no cancer in TURP specimen and were followed with a median follow-up of 9 months. Persistently rising PSA values were noted for 2 of these 6 patients. However, on repeated prostate biopsies, no signs of prostate cancer were detected. Puppo [59] concluded that TURP together with lateral extended prostate biopsies had a high diagnostic power in patients with previously negative extended prostate biopsies and rising PSA levels.

Several authors investigated the value of new imaging techniques that can possibly be used for targeted biopsies. A first new emerging and promising technique is contrast-enhanced ultrasound of the prostate (CEUS). This technique overcomes classical limitations of conventional ultrasonography in the B-mode imaging of parenchymal disease. With CEUS, the blood flow in the prostate can be investigated which will result in a better detection of abnormal micro- and macro-vascular lesions. Applying CEUS targeted biopsies, more cancers can be detected in comparison with systematic ultrasound guided biopsies [60–62]. In a multicentre European study, this technique was further evaluated [63]. Cancer was visualised and localised in 78%. However, further studies to confirm these results have to be initiated. Other authors performed research on real time elastography (RTE). With this technique, tissue stiffness is investigated as this is related to cancer high cell density. Additionally, RTE can be used for targeted biopsies. However, also for this technique further studies are needed to approve the value in prostate cancer imaging and targeted biopsies [64–68]. Another innovative technique in prostate cancer imaging and targeted biopsies is magnetic resonance (MR) and MR-guided biopsies of the prostate. This technique is well discussed in a recent review by Pondman et al. [69]. However, this technique also needs further evaluation.

In our series of studies [4, 70–72], we included a population with very specific characteristics that are notwithstanding regularly encountered in a urological practice. Therefore, we investigated patients with elevated and/or rising PSA, minor LUTS, negative DRE and TRUS, and (multiple) negative extended prostate biopsies. In this group of patients, we found that BOO is extremely likely to occur [4]. In a retrospective analysis of 82 patients [71], 74 patients were shown to suffer from BPH after TURP. In these 74 patients, only 3 patients (4.1%) had an equivocal PdetQmax (detrusor pressure at maximum flow) according to Abram–Griffiths [3], while nearly all patients (95.9%) were clearly obstructed with a mean PdetQmax of 89.5 cm H2O (range 20–200 cm H2O). In a prospective group of 33 patients, mean PdetQmax was 80.3 cm H2O (range 40–150 cm H2O) [72]. When TURP was performed in patients with these characteristics, this resulted in a symptomatic benefit (international prostate symptoms score [IPSS]/quality of life) and (super)normalisation of PSA levels both in our retrospective and prospective study [71, 72]. Most of the patients seemed to have BPH (retrospective study: 74/82 = 90.2%; prospective study: 27/33 = 81.8%). However, a few subjects suffered aggressive prostate cancer (taking into account the age of the subject, the Gleason score, and the amount of cancer cells) that needed further treatment [73, 74]. This was the case in 7 of 8 non-BPH patients in the retrospective analysis (n = 82) [71] and in 2 of 6 non-BPH patients in our prospective analysis (n = 33) [72]. On the other hand, in 1 of 8 non-BPH patients (n = 82) [71] and in 4 of 6 (n = 33) non-BPH patients [72], unaggressive prostate cancer was found. For these patients, watchful waiting was proposed. These results were confirmed in a long-term follow-up analysis with a mean follow-up of 61.5 months. In the same analysis, we found 1 patient (out of 36) who had a persistently rising PSA that resulted in positive extended prostate biopsies 4 years after TURP. This patient received further treatment with radical retropubic prostatectomy and has a tumour-free follow-up of 36 months [71].

As already mentioned, in our series of studies, most patients proved to have BPH after TURP (90.2% retrospective series; 81.8% in prospective series; 93.9% in prospective series with no aggressive cancer, only small amount of cancer cells or BPH). This implies that in this particular group of patients, even PCA3 testing, saturation prostate, biopsies, CEUS, RTE, and MR-guided biopsies will remain negative, since there is no cancer to be found. When in this group of patients’ PSA remains elevated or even rises, confusion will increase and patients cannot be submitted for ever to high-tech, cumbersome, expensive new investigations such as PCA3, CEUS, RTE, or MR. Additionally, it should also be emphasised that even new technologies have false-positive and false-negative result. Last but not least, most of these new investigations have to be investigated more thoroughly in the future. Considering these remarks, no clear answer will be found in this group of patients explaining the elevated and/or rising PSA levels. Moreover, it should be emphasised that we found in our series that in patients who underwent a radical prostatectomy, cancer was mainly located anteriorly in the peripheral zone, which is not easily accessible for prostate biopsies regardless of the targeting technique.

Proposal of a new algorithm in patients with elevated and/or rising PSA, minor LUTS, normal DRE and/or TRUS, and (multiple) negative extended prostate biopsies

Patients showing abnormal screening parameters, but with a negative cancer screening result, can be terrified because there is no answer for their abnormal values [75–77]. For example, Katz [51] showed that men with abnormal values observed during prostate cancer screening, have an increased cancer-related worry and show more problems with sexual function despite their negative biopsy results. Furthermore, we know that medical treatment has no effect on PSA levels (in case of α1 blockers) or a heterogeneous effect on PSA levels (in case of 5α reductase inhibitors) [78, 79]. Concerning 5α reductase inhibitors, Brawer [78] showed “the multiply by two rule” is not correct.

We also know that if BOO is not treated, patients are at increased risk of detrusor decompensation and/or renal insufficiency [80, 81]. Taking into account the economic aspects of the different treatments for BPH [82–84] and knowing that TURP should no longer be seen as an invasive treatment [85–89], offering TURP to these patients can be a valuable alternative strategy after BOO was proven with urodynamic evaluation, since pressure-flow studies can exclude patients who will not benefit from TURP. Moreover, the pressure-flow studies provide great predictive value of clinical improvement after TURP. The worse the degree of BOO, the higher the efficacy of TURP seemed to be [90–93]. Therefore, we suggest that in these patients with elevated and/or rising PSA level, and/or abnormal PSA velocity, and/or abnormal PSA density, and/or abnormal PSA ratio together with minor LUTS and negative DRE and TRUS, extended prostate biopsies should be taken with at least 12 cores (Fig. 1). Special attention should be taken for lateral and anterior peripheral biopsies as well as transition zone biopsies. If patients suffer from mild LUTS (IPSS 0–7), at least one series of repeated extended prostate biopsy should be taken (Fig. 1). In patients with moderate LUTS (IPSS 8–19), one well-performed extended prostate biopsy should be sufficient (P = 0.012, [76]). If extended prostate biopsies remain negative, patients should be offered an urodynamic examination with pressure-flow analysis (Fig. 1). One can expect these patients to have an obstructive pressure-flow value (or at least equivocal). In that case, TURP can be discussed and proposed (Fig. 1). Performing TURP, special attention should be given to the anterior prostate zone.

Algorithm in patients with elevated and/or rising PSA, minor LUTS, normal DRE and/or TRUS, and (multiple) negative extended prostate biopsies. PSA prostate-specific antigen, DRE digital rectal examination, TRUS transrectal ultrasound, LUTS lower urinary tract symptoms, EPB extended prostate biopsies, IPSS international prostate symptoms score, UDO urodynamic observations, PdetQ max detrusor pressure at maximum flow, TURP transurethral resection of prostate, BPH benign prostatic hyperplasia

Conclusion

Patients with elevated and/or rising PSA, minor LUTS, normal DRE and/or TRUS, and (multiple) negative extended prostate biopsies are a conundrum. We showed that in these patients, urodynamics with pressure flowmetry should be performed since BOO can be expected. In this population, we proposed a “diagnostic” TURP with special attention for the anterior prostate. This will probably result in a (super)normalisation of PSA levels and symptomatic benefit, suggesting that BOO, even with minor LUTS, can be seen as a discomfort for patients. However, histological examination will reveal prostate cancer in few cases. This prostate cancer might be aggressive needing further treatment.

References

Kirby RS (1992) The clinical assessment of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Cancer 70:284–290. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(19920701)70:1+<284::AID-CNCR2820701316>3.0.CO;2-#

Stamey TA, Yang N, Hay AR, McNeal JE, Freiha FS, Redwine E (1987) Prostate specific antigen as a serum marker for adenocarcinoma of the prostate. N Engl J Med 317:909–916

Griffiths D, Höfner K, van Mastrigt R, Rollema HJ, Spangberg A, Gleason D (1997) Standardization of terminology of lower urinary tract function: pressure-flow studies of voiding, urethral resistance, and urethral obstruction. Neurourol Urodyn 16:1–18. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1520-6777(1997)16:1<1::AID-NAU1>3.0.CO;2-I

van Renterghem K, Van Koeveringe G, Van Kerrebroeck P (2007) Rising PSA in patients with minor LUTS without evidence of prostatic carcinoma: a missing link? Int Urol Nephrol 39:1107–1113. doi:10.1007/s11255-007-9209-7

Laguna P, Alivizatos G (2000) Prostate specific antigen and benign prostatic hyperplasia. Curr Opin Urol 10:3–8. doi:10.1097/00042307-200001000-00002

Catalona WJ, Southwick PC, Slawin KM, Partin AW, Brawer MK, Flanigan RC et al (2000) Comparison of percent free PSA, PSA density, and age-specific PSA cut-offs for prostate cancer detection and staging. Urology 56:255–260. doi:10.1016/S0090-4295(00)00637-3

Borer JG, Sherman J, Solomon MC, Plawker MW, Macchia RJ (1998) Age specific prostate specific antigen reference ranges: population specific. J Urol 159:444–448. doi:10.1016/S0022-5347(01)63945-4

Benson MC, Whang IS, Olsson CA, McMahon DJ, Cooner WH (1992) The use of prostate-specific antigen density to enhance the predictive value of intermediate levels of serum prostate-specific antigen. J Urol 147:817–821

Connolly D, Black A, Murray LJ, Napolitano G, Gavin A, Keane PF (2007) Methods of calculating prostate-specific antigen velocity. Eur Urol 52:1044–1051. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2006.12.017

Carter HB, Pearson JD, Metter JE, Chan DW, Andres R, Fozard JL, Rosner W et al (1992) Longitudinal evaluation of prostate-specific antigen levels in men without prostate disease. JAMA 267:2215–2220. doi:10.1001/jama.267.16.2215

Loeb S, Roehl KA, Catalona WJ, Nadler RB (2007) Prostate specific antigen velocity threshold for predicting prostate cancer in young men. J Urol 177:899–902. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2006.10.028

Berger AP, Deibl M, Strasak A, Bektic J, Pelzer AE, Klocker H et al (2007) Large-scale study of clinical impact of PSA velocity: long-term PSA kinetics as method of differentiating men with from those without prostate cancer. Urology 69:134–138. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2006.09.018

Catalona W, Smith D, Wolfert R, Wang TJ, Rittenhouse HG, Ratliff TL et al (1995) Evaluation of percentage of free serum prostate-specific antigen to improve specificity of prostate cancer screening. JAMA 274:1214–1220. doi:10.1001/jama.274.15.1214

Froehner M, Hakenberg OW, Koch R, Schmidt U, Meye A, Wirth MP (2006) Comparison of the clinical value of complexed PSA and total PSA in the discrimination between benign prostatic hyperplasia and prostate cancer. Urol Int 76:27–30. doi:10.1159/000089731

Linton HJ, Marks LS, Millar LS, Knott CL, Rittenhouse HG, Mikolajczyk SD (2003) Benign prostate-specific antigen (BPSA) in serum is increased in benign prostate disease. Clin Chem 49:253–259. doi:10.1373/49.2.253

Khan MA, Sokoll LJ, Chan DW, Mangold LA, Mohr P, Mikolajczyk SD et al (2004) Clinical utility of proPSA and “benign” PSA when percent free PSA is less than 15%. Urology 64:1160–1164. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2004.06.033

Slawin KM, Shariat S, Canto E (2005) BPSA: a novel serum marker for benign prostatic hyperplasia. Rev Urol 7(S8):S52–S56

Stephan C, Jung K, Lein M, Diamandis EP (2007) PSA and other tissue kallikreins for prostate cancer detection. Eur J Cancer 43:1918–1926. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2007.06.006

Marks LS, Fradet Y, Deras IL, Blase A, Mathis J, Aubin SM et al (2007) PCA3 molecular urine assay for prostate cancer in men undergoing repeat biopsy. Urology 69:532–535. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2006.12.014

Hessels D, Klein Gunnewiek JM, van Oort I, Karthaus HF, van Leenders GJ, van Balken B et al (2003) DD3(PCA3)-based molecular urine analysis for the diagnosis of prostate cancer. Eur Urol 44:8–15. doi:10.1016/S0302-2838(03)00201-X

van Gils MP, Hessels D, van Hooij O, Jannink SA, Peelen WP, Hanssen SL et al (2007) The time-resolved fluorescence-based PCA3 test on urinary sediments after digital rectal examination; a Dutch multicenter validation of the diagnostic performance. Clin Cancer Res 13:939–943. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2679

Haese A, de la Taille A, van Poppel H, Marberger M, Stenzl A, Mulders PF et al (2008) Clinical utility of the PCA3 urine assay in European men scheduled for repeat biopsy. Eur Urol 54:1081–1088. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2008.06.071

Deras IL, Aubin SM, Blase A, Day JR, Koo S, Partin AW et al (2008) PCA3: a molecular urine assay for predicting prostate biopsy outcome. J Urol 179:1587–1592. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2007.11.038

Hodge K, McNeal J, Terris M, Stamey TA (1989) Random systematic versus directed ultrasound guided transrectal core biopsies of the prostate. J Urol 142:71–75

Eskew A, Bare R, McCullough D (1997) Systematic 5 region prostate biopsy is superior to sextant method for diagnosing carcinoma of the prostate. J Urol 157:199–203. doi:10.1016/S0022-5347(01)65322-9

Gore JL, Shariat SF, Miles BJ, Kadmon D, Jiang N, Wheeler TM et al (2001) Optimal combinations of systematic sextant and laterally directed biopsies for the detection of prostate cancer. J Urol 165:1554–1559. doi:10.1016/S0022-5347(05)66347-1

Arnold P, Niemann T, Bahnson R (2001) Extended sector biopsy for detection of carcinoma of the prostate. Urol Oncol 6:91–93. doi:10.1016/S1078-1439(00)00111-3

Durkan GC, Sheikh N, Johnson P, Hildreth AJ, Green DR (2002) Improving prostate cancer detection with an extended-core transrectal ultrasonography-guided prostate biopsy protocol. BJU Int 89:33–39. doi:10.1046/j.1464-410X.2002.02555.x

Matsumoto K, Egawa S, Satoh T, Kuruma H, Yanagisawa N, Baba S (2006) Computer simulated additional deep apical biopsy enhances cancer detection in palpably benign prostate gland. Int J Urol 13:1290–1295. doi:10.1111/j.1442-2042.2006.01557.x

Lui P, Terris M, McNeal J, Stamey TA (1995) Indications for ultrasound guided transition zone biopsies in the detection of prostate cancer. J Urol 153:1000–1003. doi:10.1016/S0022-5347(01)67621-3

Bazinet M, Karakiewicz P, Aprikian A, Trudel C, Aronson S, Nachabé M et al (1996) Value of systematic transition zone biopsies in the early detection of prostate cancer. J Urol 155:605–606. doi:10.1016/S0022-5347(01)66463-2

Terris MK, Pham TQ, Issa MM, Kabalin JN (1997) Routine transition zone and seminal vesicle biopsies in all patients undergoing transrectal ultrasound guided prostate biopsies are not indicated. J Urol 157:204–206. doi:10.1016/S0022-5347(01)65325-4

Fleshner N, Fair W (1997) Indications for transition zone biopsy in the detection of prostatic carcinoma. J Urol 157:556–558. doi:10.1016/S0022-5347(01)65200-5

Guichard G, Larrré S, Gallina A, Lazar A, Faucan H, Chemama S et al (2007) Extended 21-sample needle biopsy protocol for diagnosis of prostate cancer in 1000 consecutive patients. Eur Urol 52:430–435. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2007.02.062

Scattoni V, Zlotta A, Montironi R, Schulman C, Rogatto P, Montorsi F (2007) Extended and saturation prostatic biopsy in the diagnosis and characterisation of prostate cancer: a critical analysis of the literature. Eur Urol 52:1309–1322. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2007.08.006

Ashley RA, Inman BA, Routh JC, Mynderse LA, Gettman MT, Blute ML (2008) Reassessing the diagnostic yield of saturation biopsy of the prostate. Eur Urol 53:976–983. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2007.10.049

Raaijmakers R, Kirkels W, Roobol M, Wildhagen MF, Schrder FH (2002) Complication rates and risk factors of 5802 transrectal ultrasound-guided sextant biopsies of the prostate within a population-based screening program. Urology 60:826–830. doi:10.1016/S0090-4295(02)01958-1

Djavan B, Ravery V, Zlotta A, Dobronski P, Dobrovits M, Fakhari M et al (2001) Prospective evaluation of prostate cancer detected on biopsies 1, 2, 3 and 4: when should we stop? J Urol 166:1679–1683. doi:10.1016/S0022-5347(05)65652-2

Djavan B, Fong YK, Ravery V, Waldert M, Wiunig C, Fong YK et al (2005) Are repeat biopsies required in men with PSA levels ≤4 ng/ml? A multiinstitutional prospective European study. Eur Urol 47:38–44. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2004.07.024

Morote J, Lopez M, Encabo G, de Torres IM (2000) Effect of inflammation and benign prostatic enlargement on total and percent free serum prostatic specific antigen. Eur Urol 37:537–540. doi:10.1159/000020190

Nickel JC, Young DI, Boag S (1999) Asymptomatic inflammation and/or infection in benign prostatic hyperplasia. BJU Int 84:976–981. doi:10.1046/j.1464-410x.1999.00352.x

Chang SG, Kim CS, Jeon SH, Kim YW, Choi BY (2006) Is chronic inflammatory change in the prostate the major cause of rising serum prostate-specific antigen in patients with clinical suspicion of prostate cancer? Int J Urol 13:122–126. doi:10.1111/j.1442-2042.2006.01244.x

Demark-Wahnefried W, Moyad MA (2007) Dietary intervention in the management of prostate cancer. Curr Opin Urol 17:168–174. doi:10.1097/MOU.0b013e3280eb10fc

Jatoi A, Burch P, Hillman D, Vanyo JM, Dakhil S, Nikcevich D et al (2007) A tomato-based, lycopene-containing intervention for androgen-independent prostate cancer: results of a phase II study from the North Central Cancer Treatment group. Urology 69:289–294. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2006.10.019

Kirsh VA, Mayne ST, Peters U, Chatterjee N, Leitzmann MF, Dixon LB et al (2006) A prospective study of lycopene and tomato product intake and risk of prostate cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 15:92–98. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0563

Eastham JA, Riedel E, Latkany L, Fleisher M, Schatzkin A, Lanza E et al (2003) Dietary manipulation, ethnicity, and serum PSA levels. Urology 289:677–682. doi:10.1016/S0090-4295(03)00576-4

Laniado ME, Ockrim JL, Marronaro A, Tubaro A, Carter SS (2004) Serum prostate-specific antigen to predict the presence of bladder outlet obstruction in men with urinary symptoms. BJU Int 94:1283–1286. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.2004.05158.x

Roehrborn CG, McConnell JD, Lieber M, Kaplan S, Geller J, Malek GH et al (1999) Serum prostate-specific antigen concentration is a powerful predictor of acute urinary retention and need for surgery in men with clinical benign prostatic hyperplasia. Urology 53:473–480. doi:10.1016/S0090-4295(98)00654-2

Roehrborn CG, McConnell JD, Bonilla J, Rosenblatt S, Hudson PB, Malek GH et al (2000) Serum prostate specific antigen is a strong predictor of future prostate growth in men with benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Urol 163:13–20. doi:10.1016/S0022-5347(05)67962-1

Mochtar CA, Kiemeney LALM, Laguna MP, van Riemsdijk MM, Barnett GS, Debruyne FM et al (2005) Prognostic role of prostate-specific antigen and prostate volume for the risk of invasive therapy in patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia initially managed with alpha1-blockers and watchful waiting. Urology 65(2):300–305. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2004.09.030

Bratt O (2006) The difficult case in prostate cancer diagnosis—when is a “diagnostic TURP” indicated. Eur Urol 49:769–771. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2006.01.010

Puppo P (2007) Repeated negative prostate biopsies with persistently elevated or rising PSA: a modern urologic dilemma. Eur Urol 52:639–641. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2007.04.004

Rovner ES, Schanne FJ, Malkowicz SB, Wein AJ (1997) Transurethral biopsy of the prostate for persistently elevated or increasing prostate specific antigen following multiple negative transrectal biopsies. J Urol 158:138–142. doi:10.1097/00005392-199707000-00042

Kitamura H, Masumori N, Tanuma Y, Yanase M, Itoh N, Takahashi A et al (2002) Does transurethral resection of the prostate facilitate detection of clinically significant prostate cancer that is missed with systematic sextant and transition zone biopsies? Int J Urol 9:95–99. doi:10.1046/j.1442-2042.2002.00428.x

Zigeuner R, Schips L, Lipsky K, Auprich M, Salfellner M, Rehak P et al (2003) Detection of prostate cancer by TURP or open surgery in patients with previously negative transrectal prostate biopsies. Urology 62:883–887. doi:10.1016/S0090-4295(03)00663-0

Özden C, Inal G, Asan Ö, Yazici S, Ozturk B, Cetinkaya M (2003) Detection of prostate cancer and changes in prostate-specific antigen (PSA) six months after surgery for benign prostatic hyperplasia in patients with elevated PSA. Urol Int 71:150–153. doi:10.1159/000071837

Radhakrishnan S, Dorkin TJ, Sheikh N, Greene DR (2004) Role of transition zone sampling by TURP in patients with raised PSA and multiple negative transrectal ultrasound-guided prostatic biopsies. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis 7:338–342. doi:10.1038/sj.pcan.4500756

Philip J, Dutta Roy S, Scally J, Foster CS, Javlé P (2005) Importance of TURP in diagnosing prostate cancer in men with multiple negative biopsies. Prostate 64:200–202. doi:10.1002/pros.20239

Puppo P, Introini C, Calvi P, Naselli A (2006) Role of transurethral resection of the prostate and biopsy of the peripheral zone in the same session after repeated negative biopsies in the diagnosis of prostate cancer. Eur Urol 49:873–878. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2005.12.064

Mitterberger M, Pelzer A, Colleselli D, Bartsch G, Strasser H, Pallwein L et al (2007) Contrast-enhanced ultrasound for diagnosis of prostate cancer and kidney lesions. Eur J Radiol 64:231–238. doi:10.1016/j.ejrad.2007.07.027

Pallwein L, Mitterberger M, Gradl J, Aigner F, Horninger W, Strasser H et al (2007) Value of contrast-enhanced ultrasound and elastography in imaging of prostate cancer. Curr Opin Urol 17:39–47. doi:10.1097/MOU.0b013e328011b85c

Tang J, Yang JC, Luo Y, Li J, Li Y, Shi H (2008) Enhancement characteristics of benign and malignant focal peripheral nodules in the peripheral zone of the prostate gland studied using contrast-enhanced transrectal ultrasound. Clin Radiol 63:1086–1091. doi:10.1016/j.crad.2007.11.026

Wink M, Frauscher F, Cosgrove D, Chapelon JY, Palwein L, Mitterberger M et al (2008) Contrast-enhanced ultrasound and prostate cancer— a multicentre European research coordination project. Eur Urol 54:982–992. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2008.06.057

Garra BS (2007) Imaging and estimation of tissue elasticity by ultrasound. Ultrasound Q 23:255–268. doi:10.1097/ruq.0b013e31815b7ed6

Nelson ED, Slotoroff CB, Gomella LG, Halpern EJ (2007) Targeted biopsy of the prostate: the impact of color Doppler imaging and elastography on prostate cancer detection and Gleason score. Urology 70:1136–1140. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2007.07.067

Pallwein L, Aigner F, Faschingbauer R, Pallwein E, Pinggera G, Bartsch G et al (2008) Prostate cancer diagnosis: value of real-time elastography. Abdom Imaging 33:729–735. doi:10.1007/s00261-007-9345-7

Salomon G, Köllerman J, Thederan I, Chun FK, Budäus L, Schlomm T et al (2008) Evaluation of prostate cancer detection with ultrasound real-time elastography: a comparison with step section pathological analysis after radical prostatectomy. Eur Urol 54:1354–1362. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2008.02.035

Kamoi K, Okihara K, Ochiai A, Ukimura O, Mizutani Y, Kawauchi A et al (2008) The utility of transrectal real-time elastography in the diagnosis of prostate cancer. Ultrasound Med Biol 34:1025–1032. doi:10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2007.12.002

Pondman KM, Fütterer JJ, ten Haken B, Schutlze Kool LJ, Witjes JA, Hambrock T et al (2008) MR-guided biopsy of the prostate: an overview of techniques and a systematic review. Eur Urol 54:517–527. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2008.06.001

van Renterghem K, Van Koeveringe G, Achten R, Van Kerrebroeck P (2007) Clinical relevance of transurethral resection of the prostate in “asymptomatic” patients with an elevated prostate-specific antigen level. Eur Urol 52:819–826. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2007.03.055

van Renterghem K, Van Koeveringe G, Achten R, Van Kerrebroeck P (2009) Long-term clinical outcome of a diagnostic transurethral resection of the prostate in patients with an elevated prostate-specific antigen level and minor lower urinary tract symptoms. Urol Int (accepted for publication)

van Renterghem K, Van Koeveringe G, Achten R, van Kerrebroeck P (2008) Prospective study of the clinical outcome of a TURP in patients with an elevated prostate specific antigen level, minor lower urinary tract symptoms and proven bladder outlet obstruction. Eur Urol 54:1385–1392. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2008.06.069

Eastham JA, Kattan MW, Fearn P, Fisher G, Berney DM, Oliver T et al (2008) Local progression among men with conservatively treated localized prostate cancer: results from the Transatlantic Prostate Group. Eur Urol 53:347–354. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2007.05.015

Cheng L, Bergstralh EJ, Scherer BG, Neumann RM, Blute ML, Zincke H et al (1999) Predictors of cancer progression in T1a prostate adenocarcinoma. Cancer 85:1300–1304. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19990315)85:6<1300::AID-CNCR12>3.0.CO;2-#

Aro AR, Pilvikki Absetz S, van Elderen TM, van der Ploeg E, van der Kamp LJ (2000) False-positive findings in mammography screening induces short-term distress-breast cancer-specific concern prevails longer. Eur J Cancer 26:1089–1097. doi:10.1016/S0959-8049(00)00065-4

Lipkus IM, Halabi S, Strigo TS, Rimer BK (2000) The impact of abnormal mammograms on psychological outcomes and subsequent screening. Psychooncology 9:402–410. doi:10.1002/1099-1611(200009/10)9:5<402::AID-PON475>3.0.CO;2-U

Katz DA, Jarrard DF, McHorney CA, Hillis SL, Wiebe DA, Fryback DG (2007) Health perceptions in patients who undergo screening and workup for prostate cancer. Urology 69:215–220. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2006.09.059

Brawer MK, Lin DW, Williford WO, Jones K, Lepor H (1999) Effect of finasteride and/or terazosin on serum PSA: results of VA cooperative study #359. Prostate 39:234–239. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0045(19990601)39:4<234::AID-PROS3>3.0.CO;2-4

Pannek J, Marks LS, Pearson JD, Rittenhouse HG, Chan DW, Shery ED et al (1998) Influence of finasteride on free and total serum prostate specific antigen levels in men with benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Urol 159:449–453. doi:10.1016/S0022-5347(01)63946-6

Sacks SH, Aparicio SA, Bevan A, Oliver DO, Will EJ, Davison AM (1989) Late renal failure due to prostatic outflow obstruction: a preventable disease. BMJ 298:156–159. doi:10.1136/bmj.298.6667.156

Rule AD, Lieber MM, Jacobsen SJ (2005) Is benign prostatic hyperplasia a risk factor for chronic renal failure? J Urol 173:691–696. doi:10.1097/01.ju.0000153518.11501.d2

Teillac P, Scarpa RM (2006) Economic issues in the treatment of BPH. Eur Urol S5:1018–1024

Saigal C, Joyce G (2005) Economic costs of benign prostatic hyperplasia in the private sector. J Urol 173:1309–1313. doi:10.1097/01.ju.0000152318.79184.6f

Disantostefano R, Biddle A, Lavelle J (2006) An evaluation of the economic costs and patient-related consequences of treatments for benign prostatic hyperplasia. BJU Int 97:1007–1016. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.2005.06089.x

Wendt-Nordahl G, Bucher B, Häcker A, Knoll T, Alken P, Michel MS (2007) Improvement in mortality and morbidity in transurethral resection of the prostate over 17 years in a single center. J Endourol 21:1081–1087. doi:10.1089/end.2006.0370

Rassweiler J, Teber D, Kuntz R, Hofmann R (2006) Complications of transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP)—incidence, management and prevention. Eur Urol 50:969–980. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2005.12.042

Madersbacher S, Lackner J, Brössner C, Röhlich M, Stancik I, Willinger M et al (2005) Reoperation, myocardial infarction and mortality after transurethral and open prostatectomy: a nation-wide, long term analysis of 23.123 cases. Eur Urol 47:499–504. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2004.12.010

Reich O, Gratzke C, Stief CG (2006) Techniques and long-term results of surgical procedures for BPH. Eur Urol 49:970–978. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2005.12.072

Müntener M, Aellig S, Küttel R, Gehrlach C, Hauri D, Strebel RT (2006) Peri-operative morbidity and changes in symptom scores after transurethral prostatectomy in Switzerland: results of an independent assessment of outcome. BJU Int 98:381–383. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06256.x

Hakenberg OW, Pinnock CB, Marshall VR (2003) Preoperative urodynamic and symptom evaluation of patients undergoing transurethral prostatectomy: analysis of variables for outcome. BJU Int 91:375–379. doi:10.1046/j.1464-410X.2003.04078.x

Rodrigues P, Lucon AM, Freire GC, Arap S (2001) Urodynamic pressure flow studies can predict the clinical outcome after transurethral prostatic resection. J Urol 165:499–502. doi:10.1097/00005392-200102000-00033

Tanaka Y, Masumori N, Itoh N, Furuya S, Ogura H, Tsukamoto T (2006) Is the short-term outcome of transurethral resection of the prostate affected by preoperative degree of bladder outlet obstruction, status of detrusor contractility or detrusor overactivity? Int J Urol 13:1398–1404. doi:10.1111/j.1442-2042.2006.01589.x

Seki N, Takei M, Yamaguchi A, Naito S (2006) Analysis of prognostic factors regarding the outcome after transurethral resection for symptomatic benign prostatic enlargement. Neurourol Urodyn 25:428–432. doi:10.1002/nau.20262

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Sven Deferme who provided medical writing services on behalf of PharmaXL.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

van Renterghem, K., Van Koeveringe, G., Achten, R. et al. A new algorithm in patients with elevated and/or rising prostate-specific antigen level, minor lower urinary tract symptoms, and negative multisite prostate biopsies. Int Urol Nephrol 42, 29–38 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11255-009-9596-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11255-009-9596-z