Abstract

Educational design research yields design knowledge, often in the form of design principles or guidelines that provide the rationale or ‘know-why’ for the design of educational interventions. As such, design principles can be utilized by designers in contexts other than the research context in which they were generated. Although research has shown that quality support is important for design success, less is known about processes that promote utilization of design principles as the rationale for instructional design. In this study we therefore explored an intervention for promoting the utilization of a set of research-based design principles in educational practice. This intervention aimed to promote utilization through enhancing perceived usefulness of the design principles by design teams in various contexts. The set of design principles that was utilized by the design teams in this study underpins the design of so-called hybrid learning configurations that are situated at the interface between school and workplace. The intervention was developed from the perspective of boundary crossing theory and was conducted with four different design teams. It was evaluated by way of a questionnaire and a dialogue with members of the design teams. This boundary crossing intervention appeared to bring about the desired outcomes. Most of the design team members considered the set of design principles useful in several different ways and they expected that utilization of the principles would lead to an improved learning configuration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Educational design research (EDR) is a research approach that combines scientific investigation with the construction of solutions to problems that arise in educational practice (McKenney and Reeves 2012). EDR typically yields design principles that can be used as heuristic guidelines for educational improvements (Lakkala et al. 2012). These design principles are intended to be utilized in contexts other than the one in which they were generated. As such, design principles can promote collaborative knowledge building in a range of communities that are involved in designing and exploring educational interventions. They can also assist novice designers in creating effective interventions (Kali et al. 2009).

The designers of educational interventions can be individual teachers, teacher teams or interprofessional design teams (Kali et al. 2015). In design teams a shared vision and goal is essential (De Koster et al. 2012). Design principles can provide this vision or rationale or ‘know-why’ for the design (McKenney et al. 2015; Könings et al. 2007; Kali 2006). They do not prescribe how an intervention should be designed, because each intervention should be geared towards the characteristics of its specific context. Therefore, utilizing design principles for designing an intervention can be viewed as an analytical, but also as a creative process (McKenney and Reeves 2012).

Although research has demonstrated that high-quality support is crucial for design success (Kali and Ronen-Fuhrman 2011), its focus has been mainly on the process of curriculum design and pedagogical expertise (Huizinga et al. 2014). Less is known about processes that promote utilization of design principles as the rationale for instructional design, although an interest in these processes is gaining momentum in the field of education (McKenney et al. 2015).

Design principles, as a research outcome which is used in practice, connect the worlds of design research and educational practice by crossing the boundary between those two worlds (e.g. Klerkx et al. 2012). In this study we investigate how this process can be facilitated. We developed and evaluated a so-called boundary crossing intervention in order to promote utilization of a set of research-based design principles in practice. The intervention aims to enhance perceived usefulness of the design principles, where there is the assumption that when it does, the likelihood of those principles actually being used in practice will increase as well.

The set of design principles that is utilized by design teams in this study underpins the design of so-called ‘hybrid learning configurations’ at the interface between school and workplace. Cremers et al. (2016) define a hybrid learning configuration (HLC) as a social practice around ill-defined, authentic tasks or issues whose resolution requires transboundary learning by transcending disciplines, traditional structures and sectors, and forms of learning. In HLCs working and learning are integrated as students work on assignments from clients or other stakeholders in the community (Huisman et al. 2010; Zitter 2010; Zitter and Hoeve 2012).

In order to explore how a boundary crossing intervention could enhance perceived usefulness of design principles by HLC design teams, we used a design research approach (McKenney and Reeves 2012). The overall research question was:

To what extent does a boundary crossing intervention enhance perceived usefulness of a set of design principles for hybrid learning configurations by interprofessional design teams?

Sub questions relating to content and form of the intervention were:

To what extent do participants perceive the set of design principles as valuable?

In which ways does the intervention enhance perceived usefulness of the set of design principles?

We will first introduce the set of design principles for HLCs. Next we present the theoretical framework that underpins our boundary crossing intervention. Then we describe the construction, implementation and evaluation of the intervention, followed by the findings. We draw conclusions about the intervention’s outcomes and discuss in which ways the intervention contributed to these outcomes. Finally, we reflect on this study and offer suggestions for further research.

Design principles for hybrid learning configurations

The set of design principles for HLC that was utilized by design teams in this study was generated in an EDR project (Cremers et al. 2016). The HLC that was studied was called ‘Value in the valley’, and it aimed to address an increasing demand from industry and business for professionals who are able to contribute to sustainability-driven multidisciplinary and multi-sector innovations.

The learning configuration had characteristics of an HLC; it involved a social practice around ill-defined, authentic tasks or issues whose resolution requires transboundary learning (e.g. by transcending disciplines, traditional structures and sectors, and forms of learning). It functioned as a consultancy firm in which ill-defined assignments were carried out for companies and governmental institutions in the region. For these assignments, students had to collaborate in multidisciplinary teams. For example, in the ‘Sustainable village’ assignment, a step-by-step strategy was developed for villages to become a sustainable community, and in the ‘Rain in Groningen’ assignment ideas were developed for the temporary storage of excessive rain that is predicted in local climate change scenarios.

In addition to transcending disciplines, the HLC also transcended traditional structures and sectors given that it was initiated and implemented by two Dutch institutions for senior secondary vocational education (which are called ‘MBO’ in Dutch) and two universities of applied sciences (‘HBO’ in Dutch) in collaboration with two companies. The learning processes by students as well as staff consisted of a mixture of work-based learning strategies, including organized educational activities, and self-directed learning and learning from peers and experts in working practice.

The HLC was designed, implemented and evaluated in six iterations of one semester each. During the first three iterations a set of design principles was developed that was based on theory and experience in educational practice. The underlying theoretical framework was based on the ‘trialogical approach to learning’ (Paavola and Hakkarainen 2005), in which learning is conceptualized as a combination of acquisition, participation and knowledge creation (Paavola et al. 2004). The design principles were evaluated and refined during the last three iterations, which resulted in a set of seven principles that can underpin the design of an HLC (Cremers et al. 2016). The design principles and their descriptions are presented in Table 1.

Theoretical framework

In order to develop a boundary crossing intervention that would enhance perceived usefulness of the set of design principles for HLCs, we explored which theoretical framework could underpin such an intervention.

The concept of boundary crossing was our starting point. Boundary crossing refers to making a connection between different social and cultural practices (Akkerman and Bakker 2011). This connection can be made by persons, who act and interact across different sites as ‘brokers’ (Wenger 1998), or by artefacts, the so-called boundary objects. Boundary objects are defined as entities that are to be used and adapted flexibly in several different contexts (Star and Griesemer 1989). Hence, a set of design principles can be perceived as a boundary object, as the principles cross the boundary from the research context in which they were generated to new design contexts in which they are utilized.

In the following paragraphs we discuss the nature of design principles and their utilization. Then we elaborate on the concept of boundary objects, on the conceptualization of a set of design principles as a boundary object, and on ways in which the introduction of a boundary object in new contexts can be facilitated by a so-called broker. We conclude this section with assumptions that underpin a boundary crossing intervention for enhancing perceived usefulness of a set of design principles for HLC.

Design principles

Most EDR projects strive to develop educational interventions as well as design propositions or principles that can inform the development of such interventions by others outside the original field-testing context (McKenney and Reeves 2012). The interventions can be seen as the practical output of design research, whereas the design principles can be considered the theoretical output. This theoretical output can be more general and abstract, or very specific and directive. In this study we explore utilization of a set of more abstract design principles, also referred to as ‘high-level conjectures’ or ‘meta-principles’. Such design principles indicate how to support some form of learning in general terms (Sandoval 2014) and thereby enable utilization in a range of settings in which designers develop new features in accordance with the characteristics of their particular context. Features may include artefacts, tools, activities or social and organizational aspects. For instance a feature of the design principle ‘fostering authenticity’ could be that everyone in a community relates to one another as colleagues, rather than as students and lecturers.

Design principles can be used to design new educational interventions by researchers or practitioners but also to assess or evaluate current educational practices (Lakkala et al. 2012). This process, according to McKenney and Reeves (2012), requires creative thinking or ideation alongside analytical thinking. Kali (2006) p. 198 describes the design process as follows. She states that when researchers articulate a design principle as a result of a study in a certain area, “they provide theoretical background and connect the pragmatic principles with one or more features. […] This provides field-based evidence and illustrates how the principle was applied in their specific context. […] Then, another research group uses the information provided in the design principle to design new features and explore them in new contexts”. Over time, this can result in design principles being refined, altered, supplemented or even discarded.

Design principles as boundary objects

Boundary objects can be defined as “objects which are both plastic enough to adapt to local needs and constraints of the several parties employing them, yet robust enough to maintain a common identity across sites. They are weakly structured in common use, and become strongly structured in individual-site use. They may be abstract or concrete. They have different meanings in different social worlds but their structure is common enough to more than one world to make them recognizable, a means of translation. The creation and management of boundary objects is key in developing and maintaining coherence across intersecting social worlds” (Star and Griesemer 1989 p. 393). Examples of boundary objects are electronic patient records, which can be used by diverse medical actors or institutions, and a student’s portfolio that can be used both by assessors in their educational programme and by potential employers.

In this study the ‘intersecting social worlds’ are the original research context in which the set of design principles was generated and the contexts in which the design principles are utilized. Differences between HLC contexts can be manifested in, for example, the type and number of collaborating partners (educational institutions, business, governmental or research institutions), their objectives or central issues (e.g. energy transition, healthy ageing), or in organizational and financial structures.

The set of design principles can be considered a type of boundary object that Star and Griesemer (1989) call the ‘ideal type’. It is an abstraction that can be adapted to different contexts or perspectives because it does not contain local contingencies from the common object: “All perspectives are served at once by deletion of features that are specific to each perspective” (Star and Griesemer 1989 p. 410). Therefore, the process of boundary crossing by a set of design principles can be seen as a process of first decontextualizing (i.e. viewing the design principles as abstract concepts, independently from their features in the context or perspective in which they were generated), and then recontextualizing (i.e. creatively redesigning or designing new features in another educational context). The context of an educational intervention is interpreted broadly here so as to include the actors (the practitioners who implement the intervention, e.g. Könings et al. 2007) as well as the cultural aspects, normative rules and regulations and political factors, all of which may influence the way an intervention is designed and implemented.

When a boundary object ‘travels’ or crosses the boundary from one practice to another, additional information (e.g. its inception, history, or surrounding negotiations) is often needed in order to enhance understanding by others. Star and Griesemer (1989) observed that the potential of boundary objects might not be realized if underlying cultural models remain implicit. This additional information can also be viewed as a ‘thick description’ (Geertz 1975) that provides information on the research context in which the design principles were generated. The understanding of a set of design principles can be enhanced by giving concrete examples of their application in educational practice. Kali (2006) contends that design principles become more useful for designers when they are connected with various features that exemplify how they can be applied in different contexts.

Since a set of design principles, the related context description and examples of features are rather abstract concepts, it follows that they should somehow be ‘reified’ (Wenger 1998) or materialized as a product or object that can carry the concepts to and can be used within different contexts.

Introducing boundary objects to new contexts

According to Wenger (1998), people must also accompany boundary objects in order to ensure that they are understood correctly in each context and thereby avoid the risk of divergent interpretations. When people constitute the connection between two sides of a boundary, this is referred to as ‘brokering’, a situation in which people introduce elements of one practice into another (Wenger 1998). “A broker translates knowledge created in one group into the language of another so that the new group can integrate it into its cognitive portfolio. To do this, brokers must be able to manage the relations between individuals as well as act as translators” (Kimble et al. 2010 p. 438).

For brokers in educational design settings ‘translating’ often implies that they aim to enhance understanding of the design principles and to encourage the development of features in accordance with the characteristics of that particular setting. Since the development of new features requires analytical and creative thinking (McKenney et al. 2015), we considered ‘prototyping’ (Brown 2009) an appropriate working method for generating ideas for features of an HLC, based on the design principles. Prototyping, or ‘thinking with your hands’, entails the use of physical props as a springboard for one’s imagination. “This shift from physical to abstract and back again is one of the most fundamental processes by which we explore the universe, unlock our imaginations, and open our minds to new possibilities” (Brown 2009 p 87).

Prototyping is used not only for designing tangible artefacts (e.g. Brereton and McGarry 2000), but also for designing concepts or new ideas. Holloway (2009) suggests that a prototype can be used for communication, alignment, and living requirement specifications, which enhances clarity and transparency during the production of the solution. In other words, when the ‘solution’ is a set of ideas or concepts, such as the design of an HLC, prototyping could support and enhance the collaborative design and implementation process. A prototype can be a sketch, an artefact or a role play. It gives form to an idea to learn about its strengths and weaknesses. As the design process progresses, prototypes become more detailed and more refined (Brown 2009).

Assumptions underpinning the boundary crossing intervention

The theoretical framework leads us to the following assumptions that would underpin a boundary crossing intervention that aims to enhance perceived usefulness of a set of design principles.

-

1.

The set of design principles can be considered a boundary object that falls in the category ‘ideal type’, which implies that it must be perceived as valuable across different contexts or perspectives.

-

2.

A boundary object is preferably accompanied by additional information about its original context, and examples of features or manifestations of each design principle in practice could enhance understanding in new contexts.

-

3.

The design principles, context description and exemplary features must be reified or materialized as a product that can be used in various contexts.

-

4.

Preferably, a person or ‘broker’ should introduce the design principles in a new practice (in this case an HLC design context) and thereby promote their utilization as a source of inspiration for designing or redesigning features of an HLC.

-

5.

Prototyping can promote utilization of the design principles by facilitating the generation of ideas for features of an HCL in accordance with its particular context and characteristics.

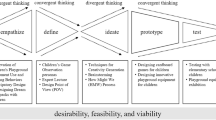

Based on these assumptions, we reified the design principles, and features and context description of the HLC ‘Value in the Valley’ in the form of a written document, which we called the ‘guidebook’. We chose to introduce the design principles to new contexts in the form of a workshop for HLC design teams, featuring a prototyping exercise. Our rationale was that workshops involve some degree of active participant action and interaction and they are therefore considered useful tools for promoting changes in the participants’ practice (Rust 1998). The researcher, who had been involved in the research project in which the set of HLC design principles had been generated, conducted the workshops, thereby acting as a broker. Thus we developed a boundary crossing intervention for HLC design teams (Fig. 1) that consisted of a guidebook (featuring the design principles for HLC) and a workshop (featuring a prototyping exercise), that was conducted by a facilitator.

Method

Because we were interested in the effectiveness of the boundary crossing intervention in different design contexts, we conducted the intervention with four different HLC design teams. First, the guidebook was constructed and tested. Then the workshop was developed. Next, the intervention was conducted and evaluated with each of the four HLC design teams. We describe these steps in detail below.

Step 1. Constructing and testing the guidebook

In order to ‘reify’ or materialize the set of design principles as a boundary object a document was constructed that listed the design principles and their description (as in Table 1) and offered a description of the original research context. For each principle, examples were given of the features of the design principles as they were manifested in the HLC ‘Value in the Valley’. The document was called ‘Guidebook for Hybrid Learning Configurations’(Supplementry material).

The first version of the guidebook was evaluated by the following four staff members of Hanze University of Applied Sciences (UAS): a lecturer/educational advisor (who offered a lecturer’s point of view), an educational consultant involved in the development of an HLC (who offered a practical point of view), an educational consultant who writes educational strategic advice (to assess the reasoning in the guidebook) and an educational/research grant writer (who checked for completeness and clarity). Feedback from experts was solicited regarding consistency of the guidebook.

This resulted in a final version that contained 3 chapters:

-

1.

An introduction that explained the guidebook’s goals, defined the HLC and gave the rationale for the development of HLCs;

-

2.

The design principles and a short description of the HLC ‘Value in the Valley’;

-

3.

The context description and the design principles with their features in ‘Value in the Valley’, along with effects of the features and conditions for these effects to occur.

For example, a feature of the design principle ‘fostering authenticity’ is working on an authentic assignment. The reported effect is that it motivates and challenges the students. A condition for this effect to occur is that a client or stakeholder is actively interested in the results. The following items were contained in the context description: activities, participants, goals and objectives, learning outcomes, vision on education and learning, and the position of the HLC.

Step 2. Developing the workshop

The set-up of the workshop was constructed by the researcher with the assistance of an expert in the field of design thinking and prototyping at Hanze UAS. The workshop consisted of a short introduction of the set of principles and a short presentation about design thinking and prototyping. Depending on the participants’ needs, the guidebook was made available to the participants before the workshop. Participants were also provided a form that they could use to take notes for each design principle.

The participants were asked to build a prototype of their current or future HLC with handicraft materials (Fig. 2). The prototype served as a metaphorical description of the initial ideas for HLC (re)design. The participants worked individually or in groups of two or three. Each group was assigned three design principles as a starting point for their prototype. Because of limited time in the workshop, the number of design principles was limited to three in order to reduce complexity for each individual group. Together each design team covered all seven design principles.

After having built the prototype, each group was given ‘diamonds’, which were shiny refrigerator magnets, and band-aids. They were instructed to place diamonds on the strong points represented by the prototype and the band-aids on the challenges or aspects that they believed needed to be developed further. Next, the groups interviewed each other about their prototypes. The diamonds and the band-aids were translated into ‘strong points’ and ‘challenges’, and these were written down on ‘sticky notes’. The sticky notes were placed on large sheets of paper and were clustered loosely around the design principles. The workshop was concluded with a short evaluation of the workshop and a discussion of the next steps that could be taken by the design team.

Step 3. Conducting the boundary crossing intervention

In this step, we studied four design teams of HLCs within Hanze UAS that either were or intended to become an HLC and had asked for support during the design or evaluation process. For each case the boundary crossing intervention was carried out in a similar way. The same version of the guidebook was used, and each workshop was conducted by the researcher who could act as a broker given that she had also been involved in the Value in the Valley HLC as an educational consultant and researcher.

In order to be able to assess the perceived usefulness of the set of design principles for both the design and the evaluation and redesign of HLCs, cases were chosen that were at different stages of development. The ‘Bureau NoorderRuimte’ (BNR) case had already been functioning as an HLC for several years, ‘Project Office Hanze Honours College’ (POHHC) only had a few characteristics of an HCL and wanted to develop further, and two HLCs were just starting to develop, namely the bachelor programme ‘Communication and International Communication’ (CO/IC), and the master programme ‘Healthy Ageing’ (MHA).

All four cases met our definition of HLC in the sense that they either were or intended to be built around more or less ill-defined tasks for or with stakeholders in the community. The resolution of these tasks required a multidisciplinary approach in three of the cases; CO/IC started with mono disciplinary assignments in the first year of the bachelor programme and intended to gradually increase complexity of the tasks in the following years. All four cases aimed to transcend traditional structures and sectors by making efforts to integrate aspects of education and work in one setting and by collaborating with stakeholders from different organizations and sectors. They also aimed to promote and integrate different forms of learning that depend on and are attuned to the type of assignments and the participants’ requirements. The HLCs can be characterized as follows.

Bureau NoorderRuimte (BNR), in English ‘Office of the Northern Region’, is part of the Centre of Applied Research on Area Development NoorderRuimte. It is a hybrid practice in which graduate students from various study programmes, lecturers, researchers, professors and practitioners work and learn together in order to solve spatial issues in the Northern region of the Netherlands and Germany. These projects are initiated by NoorderRuimte or its external environment. Four departments of Hanze UAS, namely Facility Management, Engineering, Built Environment and Business Administration are responsible for staffing Bureau NoorderRuimte with students, lecturers and researchers. Students are assisted in their personal and professional development by senior staff members of BNR.

The Project Office Hanze Honours College (POHHC) acquires projects from external clients for all students of Hanze UAS who follow an honours programme. POHHC assigns students to clients and provides a coach (a lecturer) for each group of students. The coach awards study credits at the end of a project (which can vary in length) based on several criteria: the product delivered by the students, client satisfaction and the extent to which students have been engaged and have realized their individual learning outcomes. The next step for POHHC would be to design organizational, cultural and educational aspects more explicitly and to further attune them in ways that better facilitate the students’ learning and assessment.

The bachelor programme ‘Communication and International Communication’ (CO/IC) is a regular study programme that is being redesigned as an HLC. The new curriculum is intended to function as a hybrid working and learning environment in which the students work on assignments from clients starting on the first day of their study. The physical, organizational and cultural environment is intended to reflect an authentic working context that is interwoven with ‘regular’ courses or educational activities.

The Master Healthy Ageing (MHA) is a completely new master programme. It aims to educate working health professionals from different sectors with a bachelor degree to become ‘healthy ageing professionals’. This new type of professional conducts transition processes within the health sector that require multi-stakeholder collaboration and learning. The master programme wishes to provide a suitable working and learning environment by designing it as an HLC. Table 2 provides an overview of the four cases.

Step 4. Evaluating the boundary crossing intervention

The effectiveness of the intervention was evaluated both as a direct outcome: ‘Is the set of design principles considered useful for evaluation and redesign of the HCL?’, and as more indirect outcome, the possible benefits of utilizing the design principles: ‘Is utilization of the set of design principles expected to lead to an improved HLC?’.

The intervention was evaluated with respect to content (the set of design principles) and form. The perceived value of the set of design principles was made operational by asking the participants if they considered the set to be clear, relevant, and complete. The form of the boundary crossing intervention was evaluated by questions about the usage of the guidebook, the participants’ perception of the workshop (in particular the prototyping exercise) and the role of the facilitator. In addition, information on the participants’ expectations and recommendations for improvement of the intervention in general were solicited.

The workshop was evaluated by a short discussion between the workshop facilitator and the participants at the end of each workshop. This oral evaluation concerned the workshop in general, the role of the workshop facilitator and the prototyping exercise. The workshops were audio-recorded for that purpose. In addition, a digital questionnaire was sent to the participants of the four workshops. For each question, respondents could answer “Yes” or “No”, and they were provided with boxes for elaboration on their answer. The last question provided space for any additional remarks by the respondents. The questions were the same for each HLC but the term HLC was ‘personalized’ in each case. The questionnaire was emailed to the workshop participants the day after the workshop. Table 3 shows how the evaluation topics were represented in questions to the participants.

A total of 32 participants (out of 44) responded to the questionnaire. Table 4 shows for each HLC how many of the workshop participants responded to the questionnaire.

Findings

First we will present the findings that concern the perceived usefulness of the set of design principles. Then we discuss to what extent the participants considered the set of design principles valuable (relevant, complete and clear). We conclude this section with an evaluation of the elements of the boundary crossing intervention (guidebook, workshop and facilitator).

Usefulness of the design principles

The set of design principles was considered a source of inspiration and new ideas by BNR and MHA participants. The set also helped determine “where we stand now, what we are already doing and what to develop further. By identifying strong points and issues for further development, the set is useful for evaluation and improvement” (BNR).

28 out of 32 participants from three different cases confirmed that the set of design principles helped them structure their knowledge of HLC and get an overview of what is involved when designing an HLC. The set of principles was viewed as a kind of checklist by participants of CO/IC and MHA: “the set makes clear what you have to keep in mind when developing an HLC”. MHA participants also said that it structured thinking about the design and enabled choices to be made more consciously. BNR and MHA participants reported that working with the principles made them see more coherence and alignment between the features of their HLC. They became aware that the set of principles is relevant as a whole (CO/IC) and that each principle influences the result.

The design principles were also seen as a shared frame of reference (MHA) that delimits the playing field (POHHC). MHA participants saw the design principles as “a way to clarify our criteria and get consensus about them”. The workshop also was viewed as a way of “making the concept alive in the heads of the lecturers” (CO/IC).

Working with the design principles also made some participants reflect on their design team and on the design process. An MHA participant remarked: “We are a community of learners ourselves”. One of the BNR participants realized that “it is clear that we can make improvements, this gives starting points for further development; dealing with it in an analytic way helps to identify parts and develop them further.”

When asked whether the respondents thought that their HLC would improve by applying the set of design principles and in which way, the following answers were given.

Participants of POHHC expected that working with the design principles would provide more clarity in communication between lecturers, students, clients and other stakeholders. A common language would also result in more structure and more uniformity in working methods.

CO/IC respondents viewed the principles as way of justifying their approach as being in line with Hanze UAS’ vision on education. The fact that the design principles were underpinned by research could be a pro when the programme would be audited. Participants in three cases expected that the educational quality of their HLC would improve by using the set of design principles: “The principles provide a frame of reference for how we can offer more structure to students for carrying out their projects and for facilitating their learning processes” (POHHC) and “elements of the HLC will be better attuned to each other” (BNR). MHA participants expected that the chances of designing ‘traditional’ education activities would decrease and that the programme would be sufficiently practice-oriented if the designers incorporated the principles.

One lecturer of POHHC remarked that although the set of principles represented a framework that delimited the playing field, this would also give the designer the freedom to be flexible in their execution of the HLC: “The practical application can vary for each assignment since the role and requirements of each client can be different.”

Some of the CO/IC participants did not yet know whether the set of design principles would be useful or not. One of them commented that the set was useful “as long as we don’t apply everything at once” (CO/IC). An MHA lecturer thought that if a lecturer puts the students in charge of his or her own learning processes, the role of the lecturer changes automatically to being more like a colleague. Another response was: “We will know if the set was useful when the programme we execute has proven to be successful” (MHA).

BNR intended to use the outcomes of the workshop (namely, the strong points and challenges for the HLC) in a strategic meeting about the future of the HLC, which was already planned.

Relevance, clarity and completeness of the set of design principles

The respondents of the four cases (32) almost unanimously found the set of design principles relevant for their HLC. They also thought that the set was complete. No principles were considered either redundant or missing, except for the following two suggestions that were made in the MHA case: “Add a principle concerning the coherence between educational units within the programme”, and also a principle that would facilitate “making it fun, interesting and useful to learn from each other”. One participant from the POHHC group commented that there seemed to be some overlap in the principles in the sense that different design principles could inspire the same feature(s).

Some participants of POHHC and MHA indicated that the principles were “a bit too theoretical and abstract” and did not provide enough guidance for actually developing the HLC: “The principles are quite broad; you have to colour them by yourself”.

Workshop, guidebook and facilitator

According to most respondents, the examples of how design principles were manifested in the HLC ‘Value in the Valley’ helped them to get a better understanding of the design principles. In turn, this helped them relate the principles to their own HLC. One participant from the CO/IC group wrote the following about a feature of the design principle ‘fostering authenticity’: “The role of students as employees and lecturers as senior employees was an eye-opener for me”. Also, some participants indicated that they would have liked to read or hear more about this HLC. Others in the BNR and POHHC groups said they would have preferred to elaborate more on manifestations of the design principles in their own HLC.

Almost all respondents (29 out of 32) indicated that they had read the guidebook. The guidebook was considered relevant as a preparation for the workshop by most participants because it informed them about what the workshop would be about (BNR) and what could be expected of the workshop (MHA). It also provided common prior knowledge by defining the concepts in a way that ruled out confusion about them during the workshop (POHHC).

The respondents also mentioned other merits of the guidebook: “It provides a clear framework, the vision on this type of learning environment is described clearly and it provides focus on the subject” (MHA), “the guidebook gives a good overview of the design principles” (PBHHC, BNR), and “the design principles seem feasible” (MHA). “The guidebook makes you aware of aspects that have to be considered seriously, and it gives background information and justification of the principles” (BNR).

Respondents commented on the guidebook as being informative (PBHHC), concise, comprehensive, clear, insightful and usable (MHA). It also provided “examples of how something abstract can be applied in practice” (MHA). A respondent suggested expanding it by adding examples other than the Value in the Valley HLC (BNR).

The guidebook was found useful as a reference book when developing the HLC: “I can use it as a guideline; it gives a good idea of how an HLC can be developed” (POHHC). Some participants had expected it to be more like an instruction guide: “I miss the working method of developing an HLC; how do you proceed?” (POHHC) and “Practical application remains vague” (MHA). Other comments were that the guidebook “stimulates you to think about the HLC” (CO/IC) and that providing the guidebook before the workshop “gives you the opportunity to read it in your own time and pace” (MHA).

In all four cases the participants indicated that the workshop provided an opportunity to engage in conversation about the HLC. During this conversation, ideas were generated for the practical development of the HLC. The prototyping exercise lead to lively conversations in which many metaphors were used for aspects of the HLC. For instance, a butterfly was used to symbolize playing, flittering and discovering, which all stand for the idea that students are activated and not merely taught. In addition, the prototyping exercise itself was used as a metaphor for designing the HLC: “We don’t have the perfect tools and facilities, but we work with what we have and make the best of it!” (CO/IC). The metaphors of the diamonds and the band-aids were used during all the presentations and also after the workshop: “When we encounter a problem that we don’t know how to solve right away, we say: ‘let’s put a band-aid on that issue’” (MHA).

The participants from BNR suggested that the workshop facilitator should have focused more on BNR instead of Value in the Valley given that the guidebook containing information on that case had been read beforehand. POHHC members requested a follow-up workshop that focused specifically on their assignments.

The workshop seemed to enhance a shared image of the HLC among the team members. For CO/IC, creating a common image of the new curriculum and identifying the most urgent challenges were important steps. The relevant challenges for them were the acquisition of enough assignments from clients and the definition and implementation of new roles of the lecturers.

The MHA team valued the workshop for the opportunity to exchange ideas about the direction of development. Many practical questions, however, remained unanswered for them. For example, they still wondered which assessment methods are appropriate in a given learning community. Some of the participants (POHHC and MHA) expected to obtain more concrete ideas for developing their HLC at the end of the workshop.

The POHHC team discovered that their context or frame of reference was not sufficiently well-defined. Issues they discussed were: what do we expect from students and clients, in which directions should students develop competencies, and what are desired learning outcomes given the variety of different projects. They felt that more time was needed to elaborate on the design principles, and for this purpose a follow-up meeting was arranged. In general, the workshop was considered to be fun, pleasurable, creative, useful and meaningful. Some participants indicated a preference for doing the workshop earlier in the design process (MHA, CO/IC).

In every workshop the participants were interested in each other’s prototypes, and every prototype was discussed with the whole group. Participants appreciated each other’s efforts. Though some participants were initially reluctant to start building a prototype, in the end every participant had participated in prototype building.

Conclusions

Based on the findings we will now answer the research questions. With respect to the main research question we conclude that the participants of the intervention came to perceive the design principles as useful in different ways. According to the participants, utilization of the design principles fosters an enhanced understanding of the structure and coherence of elements of the respective HLCs, a shared image of the HLC with its strong points and challenges, and ideas and inspiration for how to (re)design the HLC. Thus the design principles, conveyed by this intervention, appeared to provide a conceptual framework for understanding and designing features of an HLC and a vocabulary for communicating design ideas.

Most of the participants expected their HLC to improve by utilizing the design principles. They indicated that this could happen in several different ways. In the design process, the set was expected to be used as a checklist and frame of reference that would foster conscious choices. In addition, using the principles was expected to lead to better communication and harmonization within the HLC and with external stakeholders. It would enable the team to base the design on an educational vision that is underpinned by research. Educational quality would be increased by better facilitating the learning process of the students and by better attuning the elements of the HLC to each other.

Although the actual development and possible improvement of the HLCs is beyond the scope of this study, we conclude that, according to the participants, using the set of design principles can potentially benefit the design of HLC by facilitating more conscious choices by the design team and by fostering better internal and external communication about both the HLC itself and the harmonization of its elements.

We will address the sub questions by relating the findings about the boundary crossing intervention (content and form) to its underpinning assumptions that were based on our theoretical framework. Our first assumption was that a boundary object (the set of design principles) must be perceived as valuable across different contexts. We found that almost all participants of the four design teams perceived the set of design principles as being relevant, clear and complete.

Second, we contended that additional information about the context in which the design principles were generated and examples of their manifestations in practice would enhance understanding in new contexts. Our findings suggest that understanding of the design principles was enhanced when participants were provided with information about the context and examples of features of the HLC in which the design principles were generated. Indeed, the contextual information about Value in the Valley helped participants to define their own context more clearly. In one case it revealed that the context (the goals, positioning, etc.) of the HLC had not yet been defined clearly, and this seemed to hinder the design process because the participants did not start the prototyping exercise until they had had a long discussion about certain aspects of the context. This suggests that decisions about the context should be made before or in early stages of the design process.

Although the features of the ‘Value in the Valley’-HLC enhanced understanding of the principles for most of the participants, there was an observable difference between the existing HLCs and the new HLCs. The designers of the existing HLCs (BNR and POHHC) would have appreciated more examples of features of their own HLC, whereas some of the designers of new HLCs (CO/IC, MHA) would have preferred more information on Value in the Valley. This suggests that (re)contextualizing is easier if there already is an existing context. Therefore, it seems advisable to attune the extent and content of exemplary features to the developmental stage of the HLC.

Our third assumption was that the boundary object, context description and exemplary features must be reified or materialized as a product that can be used in various contexts. This resulted in the guidebook, which was characterized by participants of different design teams as a reference book, as an incentive to think about HLC, and as a guideline when developing an HLC.

In addition, we proposed that a person or ‘broker’ should introduce the design principles in a new practice (in this case an HLC design context) and thereby promote their utilization as a source of inspiration for designing or redesigning features of an HLC. The researcher, who conducted the workshops to introduce the principles in new context, acted as a broker because she explained the design principles and their original context further. She also connected different practices with each other by providing examples of how the principles are manifested in several different HLCs, including the participants’ own HLC.

Our fifth assumption was that prototyping can promote utilization of the design principles by facilitating the generation of ideas for features of an HCL in accordance with its particular context and characteristics. According to the participants, the prototyping exercise promoted the exchange of ideas about further development of the HLCs. Some participants had expected that the set of design principles would provide instruction or would result in instant solutions to or decisions about practical issues, and were a bit disappointed that this was not the case. This suggests that the expectations about the usability of the design principles were not clear for every user. The workshop was appreciated for the fact that it provided an opportunity for the design teams to have conversations about the principles and their HLC.

In general we conclude that the intervention appeared to contribute to the participants’ perceived usefulness of the set of design principles by enhancing understanding and by encouraging actual utilization of the principles for their own HLC. Through the prototyping exercise the participants experienced how the design principles could be used for generating ideas for the (re)design of their HLC. Understanding of the principles was enhanced through the guidebook (reified boundary object) and the workshop facilitator (broker) by explaining the principles and providing examples of features and context information about the HLC of the original research context.

In addition, our findings suggest some refinements to the assumptions that underpinned the intervention. First, the notion that a boundary object is preferably accompanied by additional information about its original context and by examples of features or manifestations of each design principle in practice could be extended. We found that in different user-contexts there is a different need for the type of context descriptions and examples of features. Not only the original research context and features of the HLC studied there, but also examples of other contexts, including the users’ own HLC, appeared to enhance understanding of the design principles. In our study these extra examples were given by the course facilitator (the broker) but they could also be added to the guidebook.

Second, expectations about how the boundary object can and cannot be utilized should probably be managed before or at the start of actual utilization in a certain context.

Discussion

In this study we framed the set of design principles as a boundary object. One might argue that a boundary object’s main function is to facilitate collaboration among actors from different social worlds and that a set of design principles that ‘travels’ from the world of research to the world of educational design practice is not aimed at facilitating a two-way collaboration between these worlds. Therefore it could be considered incorrect to frame a set of design principles as a boundary object. Indeed, Star’s initial framing of the concept ‘boundary object’ “was motivated by the desire to analyse the nature of cooperative work in the absence of consensus” (Star 2010, p. 604). However, the defining characteristics of a boundary object by Star and Griesemer (1989) as described in our theoretical framework do not include the way in which a boundary object should be used, nor did Star intend to prescribe how anyone uses the concept (Star 2010).

Framing the set of principles as a boundary object appeared to be helpful because it supported our view of design principles as research results. In our view design principles are not merely a product that can be readily applied by a user, but rather an attempt to bring what is learned in one community (the world of research) into another (the world of educational design), in such a way that the users can adapt or ‘translate’ these results to their own needs and context. At the same time the set of design principles provides a common frame of reference among researchers and designers within or across design contexts, thereby bridging these different worlds. In our view, this aligns well with the definition of a boundary object, even if this object, in our case, would facilitate potential rather than immediate and on-going collaboration and communication among these worlds.

Another issue that deserves attention is the fact that we examined utilization of a set of HLC design principles that resulted from a single case study. Even though the principles were underpinned by theoretical concepts and educational experience and tested in practice in three consecutive iterations (Cremers et al. 2016), transposing these principles to another context might be considered problematic. According to Yin (2003) researchers should strive to validate the results of a single case study by testing them in more cases and in various contexts. In this study we checked this in a modest way by asking the participants if they thought that the set of design principles was relevant and complete, and the responses were almost unanimously affirmative.

However, as Gravemeijer and Cobb (2006, p. 45) point out, “in EDR complete replicability is neither desirable nor, perhaps, possible”. Design research aims for ecological validity, which is the idea that the (description of) the results should provide a basis for adaptation to other situations (Gravemeijer and Cobb 2006). Utilization of design principles in new contexts leads to adjustments that are geared towards the unique characteristics of that context (Kali 2006). In our study participants designed new features, suggested slightly different wording of the design principles and adjustments in the guidebook, and each design team had its own preferences for the type of features used as examples.

Some of the participants in our study expected more ‘certainties’ than the design principles were intended to offer. This suggests that there is a tension between providing guidance and directions, and opening spaces for interpretation and contextual differences in design contexts. We suspect that participants with design expertise are more comfortable with less prescriptive guidance, while novices are more comfortable with more authoritatively prescribed directions. Designing an HLC, based on a set of design principles, is a complex endeavour which is not a standard component in teacher education programmes It is a novel design task for most teacher-designers, that requires adaptive design expertise (McKenney et al. 2015). In addition, HLC design teams often include professionals from other fields outside education, who cannot be expected to have expertise in educational design. Therefore we conclude that it would be advisable to investigate which specific design support would be needed in each design team, in addition to support for utilization of design principles.

Some of the respondents indicated that the design principles seemed to overlap in the sense that different design principles could inspire the same feature(s). For example, when a feature of an HLC is ‘all stakeholders work at fixed times in the same room’, this can be inspired by the principles ‘enabling organization’ (the room being a physical facility) and ‘fostering a learning community’ (having people share a room is expected to enhance collaboration). This is in accordance with Sandoval’s (2014) model according to which design principles and features are related in multiple ways.

These multiple relationships between design principles and features suggest that having designers think about features for each separate principle, and presenting examples of features in this way (Cremers et al. 2016) is not correct. However, we also found that participants appreciated this analytical or ‘atomistic approach’ (Van Merriënboer and Kirschner 2007) in order to understand each design principle. When they built the prototypes, the participants seemed to work from a more holistic conceptualization of the set of design principles, and they did not seem to be constrained by the idea that each feature should be related to only one principle. Therefore, we conclude that it may be advisable initially to present the design principles and their related features as separate entities and to use them in a more holistic way in the actual design process.

Concluding remarks

As mentioned in the introduction, it is important that design teams of educational interventions work from a shared vision or rationale and that high-quality support is available. Both of these are crucial for successful instructional design, which, in turn, is expected to enhance learning by students and others who participate in educational interventions.

In this study we developed and evaluated an intervention that aimed to promote utilization of a set of design principles as the rationale for the design of HLCs through enhancing perceived usefulness of the principles. Our assumption was, that when design principles are perceived as being useful, this can increase the likelihood of actual use of the principles in practice. The intervention appeared to generate the desired outcomes: most of the participants considered the set of HLC design principles useful and expected that utilization of the principles would lead to an improved HLC. In addition, three of the four design teams that participated in this study indicated that they had subsequently used the design principles for the (re)design of their HLC.

These generally positive findings can be the starting point of a deeper investigation of how design teams make sense of the principles and apply them in their practical design reasoning. In addition, further research could be directed towards different ways of support for design teams. Longitudinal case studies could reveal whether the benefits of utilizing the design principles that are suggested in this study can be fully realized.

References

Brereton, M. & McGarry, B. (2000). An observational study of how objects support engineering design thinking and communication: Implications for the design of tangible media. Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, (pp. 217–224) The Hague, Netherlands: University of Queensland.

Brown, T. (2009). Change by design: How design thinking transforms organizations and inspires innovation. New York: HarperCollins Publishers.

Cremers, P. H. M., Wals, A. E. J., Wesselink, R., & Mulder, M. (2016). Design principles for hybrid learning configurations at the interface between school and workplace. Learning Environments Research, 19(3), 309–334.

De Koster, S., Kuiper, E., & Volman, M. (2012). Concept-guided development of ICT use in ‘traditional’ and ‘innovative’ primary schools: What types of ICT use do schools develop? Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 28(5), 454–464.

Geertz, C. (1975). Thick description: toward an interpretive theory of culture. In C. Geertz (Ed.), The interpretation of cultures (pp. 3–30). London: Hutchinson.

Gravemeijer, K., & Cobb, P. (2006). Design research from a learning design perspective. In J. Van den Akker, K. Gravemeijer, S. McKenney, & N. Nieveen (Eds.), Educational design research. New York: Routledge.

Holloway, M. (2009). How tangible is your strategy? How design thinking can turn your strategy into reality. Journal of Business Strategy, 30(2/3), 50–56.

Huisman, J., Bruijn, E., Baartman, L., Zitter, I., & Aalsma, E. (2010). Leren in hybride leeromgevingen in het beroepsonderwijs. Praktijkverkenning, theoretische verdieping. Utrecht: Expertisecentrum Beroepsonderwijs (ecbo).

Huizinga, T., Handelzalts, A., Nieveen, N., & Voogt, J. M. (2014). Teacher involvement in curriculum design: Need for support to enhance teachers’ design expertise. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 46(1), 33–57.

Kali, Y. (2006). Collaborative knowledge building using the design principles database. International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, 1(2), 187–201.

Kali, Y., Levin-Peled, R., & Dori, Y. J. (2009). The role of design-principles in designing courses that promote collaborative learning in higher-education. Computers in Human Behavior, 25(5), 1067–1078.

Kali, Y., McKenney, S., & Sagy, O. (2015). Teachers as designers of technology enhanced learning. Instructional Science, 43(2), 173–179.

Kali, Y., & Ronen-Fuhrmann, T. (2011). Teaching to design educational technologies. International Journal of Learning Technology, 6(1), 4–23.

Kimble, C., Grenier, C., & Goglio-Primard, K. (2010). Innovation and knowledge sharing across professional boundaries: Political interplay between boundary objects and brokers. International Journal of Information Management, 30(5), 437–444.

Klerkx, L., Van Bommel, S., Bos, B., Holster, H., Zwartkruis, J. V., & Aarts, N. (2012). Design process outputs as boundary objects in agricultural innovation projects: functions and limitations. Agricultural Systems, 113(2012), 39–49.

Könings, K. D., Brand-Gruwel, S., & van Merriënboer, J. J. (2007). Teachers’ perspectives on innovations: Implications for educational design. Teaching and Teacher Education, 23(6), 985–997.

Lakkala, M., Ilomäki, L., Paavola, S., Kosonen, K., & Muukkonen, H. (2012). Using trialogical design principles to assess pedagogical practices in two higher education courses. In A. Moen, A. I. Morch, & S. Paavola (Eds.), Collaborative knowledge creation (pp. 141–161). Rotterdam, The Netherlands: Sense Publishers.

McKenney, S., Kali, Y., Markauskaite, L., & Voogt, J. (2015). Teacher design knowledge for technology enhanced learning: An ecological framework for investigating assets and needs. Instructional Science, 43(2), 181–202.

McKenney, S., & Reeves, T. C. (2012). Conducting educational design research. Oxon, London: Routledge.

Paavola, S., & Hakkarainen, K. (2005). The knowledge creation metaphor: An emergent epistemological approach to learning. Science & Education, 14(6), 535–557.

Paavola, S., Lipponen, L., & Hakkarainen, K. (2004). Models of innovative knowledge communities and three metaphors of learning. Review of Educational Research, 74(4), 557–576.

Rust, C. (1998). The impact of educational development workshops on teachers’ practice. The International Journal for Academic Development, 3(1), 72–80.

Sandoval, W. (2014). Conjecture mapping: an approach to systematic educational design research. Journal of the learning sciences, 23(1), 18–36.

Star, S. L. (2010). This is not a boundary object: Reflections on the origin of a concept. Science, Technology and Human Values, 35(5), 601–617.

Star, S. L., & Griesemer, J. R. (1989). Institutional ecology, ‘translations’ and boundary objects: Amateurs and professionals in Berkeley’s Museum of vertebrate zoology. Social Studies of Science, 19(3), 387–420.

Van Merriënboer, J. J. G., & Kirschner, P. A. (2007). Ten steps to complex learning: A systematic approach to four-component instructional design. London: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice. Learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Yin, R. K. (2003). Case study research: Design and methods. Newbury Park, California: Sage.

Zitter, I. I. (2010). Designing for Learning: Studying learning environments in higher professional education from a design perspective (Dissertation). Utrecht, The Netherlands: Utrecht University.

Zitter, I., & Hoeve, A. (2012). Hybrid learning environments: merging learning and work processes to facilitate knowledge integration and transitions. OECD Working Papers (81). Paris: OECD Publishing.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the participants of the four case studies for their inspiring cooperation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Cremers, P.H.M., Wals, A.E.J., Wesselink, R. et al. Utilization of design principles for hybrid learning configurations by interprofessional design teams. Instr Sci 45, 289–309 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11251-016-9398-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11251-016-9398-5