Abstract

The inherent surface roughness at atomic scale contacts has profound effects on their local stresses, contact areas, and so on, which yield deviations from the predictions of continuum models. While these deviations can be interpreted as a breakdown of the models, attempts have been made to reconcile the two via different paths, e.g., proposing new methods for estimating the contact area, or filtering the contact stress fields. The applicability of the latter to randomly rough nanocontacts, however, has not yet been explored hitherto. Here, we show that this new method should be employed with care. Investigating two smooth and rough contacts, we find that the filtering method can make the stresses resemble each other by varying the filter’s resolution. Our results demonstrate that the filtering method improves comparisons between atomistic contacts and Hertz theory, while accounting for roughness in the rough contact results in more accurate solutions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

From an exhaustive investigation of nanoscale contacts by means of atomistic simulations, Luan and Robbins concluded the breakdown of continuum models in describing mechanical contacts, due to the inevitable surface roughness at the atomic scale [1, 2]. As a remedy, Mo et al. argued that a correct definition of contact area should be used for the post-processing of atomistic simulations, so that the results would be comparable with contact mechanics models [3, 4]. They proposed that instead of measuring contact area \(A_{\mathrm {c}}\) by enclosing the edges of contact with a circle or a convex hull, \(A_{\mathrm {c}}\) should be estimated via \(T_{\mathrm {c}} A_{\mathrm {a}}\), with \(T_{\mathrm {c}}\) and \(A_{\mathrm {a}}\) being the number of contacting atoms and the contact area of an individual atom, respectively. In order to utilize this method, the value of \(A_{\mathrm {a}}\) should be known. Moreover, a criterion is required for identifying the contacting atoms. This criterion may need to be defined by assuming the validity of continuum models for non-adhesive contacts [5, 6], while for the post-processing of adhesive ones, such an assumption can be avoided [7, 8]. The readers are referred to the literature, e.g. [5, 9, 10], for further details on the topic.

Very recently, Müser proposed that the results of smooth and rough nanocontacts can be compared more meaningfully to each other, if the stress fields of both are processed through the same low-pass filter [11], than if the result of a simulation with small-scale details (such as atoms, steps, etc.) is directly compared to a continuum solution of a model lacking these details. He employed two Hertzian tips (smooth and stepped), and studied their stress fields to show that applying a Gaussian filter with a resolution close to the broadest terrace of the quantized tip makes the stress distributions of both contacts indistinguishable. Hence, he concluded that a correct post-processing of atomistic and continuum solutions using appropriate filters, e.g., Gaussian ones, is required for a meaningful comparison.

This study focuses on estimating contact areas of smooth and rough nanocontacts using their filtered stress distributions. To this end, the atomistic contacts between two (smooth and rough) Hertzian rigid tips and a flat deformable substrate are examined using molecular statics. Then, the idea of smoothening the stress distributions using Gaussian filters and their effects on the final estimated interaction areas is investigated.

2 Numerical Methods

2.1 Model Setup

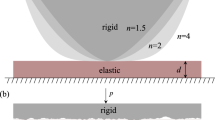

The contact is investigated by bringing a rigid indenter in contact with a deformable flat solid. The deformable solid is built from individual atoms of fcc crystal structure, with a lattice parameter of \({\text{a}}_0=5.5884\, \AA\) corresponding to calcium [12]. The simulation box has lateral lengths of \(L_{\mathrm {x}}\approx 248.4\, \AA\) and \(L_{\mathrm {y}}\approx 253.5\, \AA\) along the crystalline directions of [\(\bar{1}10\)] and [\(\bar{1}\bar{1}2\)], respectively. Moreover, the originally flat solid has a thickness of \(L_{\mathrm {z}}\approx 7.1\text { nm}\) aligned with the [111] direction. The last atomic layer at the bottom of the solid is fixed, providing the needed support for the deformable solid, while periodic boundary conditions are applied along the lateral directions.

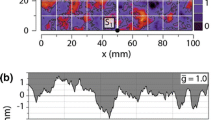

Two different rigid indenters are employed: smooth and rough. For the smooth indenter, a solid fcc structure with the lattice parameter of calcium, and with the same directions as the deformable body is generated; the thickness of the structure is selected to be three atomic layers, i.e., \({{h = 3{\text{a}}_{0} } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{h = 3{\text{a}}_{0} } {\sqrt 3 \approx 9.68{\text{ nm}}}}} \right. \kern-\nulldelimiterspace} {\sqrt 3 \approx 9.68\, \AA}}\). Then, the atoms of this structure are shifted along the z axis accordingly to follow the geometry of an elliptic paraboloid with a radius of curvature \({\textit{R}}=100\, \AA\). Finally, the height of the indenter is set to h, and the rest of the atoms are removed. The rough indenter is generated differently. First, an amorphous structure is generated using Atomsk [13], which is then subjected to a two-step cutting process: in the first step, this is truncated by a layer with thickness h, and in the second step, the positions of the atoms are compared with a Hertzian tip (\(R=100\, \AA\)); the ones located outside of the paraboloid are removed. The rough tip is not subjected to a relaxation process as it could affect its surface roughness [14] and radius of curvature. Figure 1 shows the atomic structure of these two indenters.

2.2 Simulation Setup

Interactions between atoms in the deformable body are described by the embedded atom method (EAM) potential [15] with the database developed by Sheng et al. [12]. Moreover, non-adhesive contact was simulated by manipulating a 12–6 Lennard–Jones (LJ) potential [16], by truncating it at its minimum and shifting it to the zero energy level to ensure that the force and energy go smoothly to zero at the cutoff. The LJ parameters were selected as \(\epsilon _\mathrm {LJ}=0.2145{\text { eV}}\) and \(\sigma _\mathrm {LJ}=3.5927\, \AA\) [17].

The molecular statics (MS) method is performed with LAMMPS [18], using the Polak–Ribière version of the conjugate gradient algorithm [19]. The minimization technique iteratively adjusts the position of the atoms in a direction with the steepest potential energy gradient, until the system reaches its local potential energy. The reason for choosing MS over molecular dynamics is to have better comparisons between the molecular simulations and athermal continuum models, i.e., Hertz contact mechanics in this work.

2.3 Simulation and Data Collection

The contact is simulated by moving the rigid tips toward the deformable body with a step size of \(0.1\, \AA\) for a total displacement of 5.8 nm and 6.8 nm for the smooth and rough tips, respectively. The total displacement is selected so as to be sure that the irreversible plastic deformation has started.

During the minimization process, the atoms’ positions of the tip are fixed for the selected configuration, while the atoms of the counterpart are free to interact with each other and with the tip as before. Following the minimization, the acting forces upon each atom are measured at two stages, where the interaction between the bodies is (1) on and (2) off. The normal interacting force of each atom is calculated via \(F_\mathrm {z,interact}=F_\mathrm {z,1}-F_\mathrm {z,2}\), where z refers to the normal component of force, and 1 and 2 correspond to the abovementioned states, respectively.

2.4 Binning Procedure

Once \(F_\mathrm {z,interact}\) is obtained, the xy plane of the simulation box is discretized into \(N^2\) rectangular bins, with N being the number of bins along both the x and y axes. The area of each bin is \(A_N=\ell _\mathrm {x} \ell _\mathrm {y}\), with \(\ell _\mathrm {x}\) and \(\ell _\mathrm {y}\) being the lateral lengths of a bin along the x and y axes, respectively. The applied normal stress from an atom m on a corresponding bin j is obtained from \(\sigma _{mj}={\textit{F}}_{\text {z},m}/A_N\). Then, the portion of each surrounding grid point of the bin j, i.e., \(\sigma _j\), is calculated based on the relative atom’s position on the xy plane: the lateral distances between the selected atom and a grid point i of the corresponding bin are calculated as \(\delta _{\text {x},mi}\) and \(\delta _{\text {y},mi}\). Then, a weighting parameter is introduced in the form of \(w_{mi}=b_{\text {x},mi} b_{\text {y},mi}\), with \(b_{\text {x},mi}=1-\delta _{\text {x},mi}/\ell _\mathrm {x}\) and \(b_{\text {y},mi}=1-\delta _{\text {y},mi}/\ell _\mathrm {y}\). Finally, the normal stress acting on each grid point is estimated from \(\sigma _{mi}=\sigma _{mj} w_{mi}\).

The values of \(A_N\) can be compared with the approximated contact area of an individual atom \(A_\mathrm {a,Ca}\approx 12.2\, \AA ^2\) [5] by defining a ratio \(\lambda (N)={A_N}/{A_\mathrm {a,Ca}}\). It can be found that with \(N=72\) (for the current study), this ratio would be \(\lambda \approx 1\). Various values of N ranging between 2 and 128 are used in this investigation, which are summarized in Table 1 along with their corresponding values of \(\lambda\). One may argue that \(N>72\) results in \(\lambda <1\), which is physically meaningless; accepting this argument, the possible use of gridding with \(\lambda <1\) is discussed in Sect. 3.2.

2.5 The Method for Identification of Local Stress Maxima and the Line of Maximum Gradient of Stress Distribution

The filtered stress distributions obtained from binning with \({\textit{N}}\,=\,128\) are post-processed with in-house codes written in MATLAB 9.3 particularly for this purpose. Firstly, in order to increase the accuracy of the procedure, the data are mapped onto a \(1024\times 1024\) rectangular gridded plane. Then, the local stress maxima are identified using function “imregionalmax” available via the Image Processing Toolbox 10.1. While the point of maximum stress can be easily obtained for the smooth contact, maxima in the stress distribution of the rough one have to be inspected as it is possible that various local maxima exist. Afterwards, the gradient of the stress is calculated, and the line of maximum gradient around each local stress is obtained through the following procedure.

The Cartesian coordinate is transformed into a polar one, by setting its pole at the position of the selected maximum. Then, the angular coordinate is divided into 36 equivalent sectors, so that a single point of the maximum gradient line can be identified within each one, resulting in a total of 36 data points around the selected maximum. To do so, the stress values within each sector are sorted as a function of their radius, and the local maximum with the smallest radial coordinate is selected as one point on the line of maximum gradient. After processing all 36 sectors, the coordinate system is transformed back into a Cartesian one. Once the procedure is applied to all of the identified local maxima, the contact area is estimated for the traced maximum gradient lines using function “boundary.”

3 Results and Discussion

Figure 2 shows the contact’s normal force \(F_\mathrm {z}\) as a function of indentation depth for both contacts. In order to convert the displacement to indentation depth, \(\delta _\mathrm {ind}=0\) is selected from the position of the indenter at one step prior to the initiation of interaction between the bodies, i.e., where \(F_\mathrm {z}\ne 0\).

In both contacts, the normal force increases to a maximum and is followed by a sudden drop, indicating the initiation of irreversible plastic deformation within the deformable body. By fitting a power law equation of the form \(F_\mathrm {z}=c\delta _\mathrm {ind}^e\) to the force–indentation depth curves, the values of c and e are found to be 3.5 and 1.76 for the smooth tip, and 1.61 and 2.14 for the rough one, respectively. Comparing the normal forces for the two contacts prior to the force drops, it is obvious that, at any given indentation depth, the contact force for the smooth indenter is higher than for the rough one. This is due to the higher number of interacting atoms for the case of a smooth indenter. Furthermore, it can be noted that the contact force for the rough indenter features a sudden change in its slope that first occurs at \(\delta _\mathrm {ind}=4.4\, \AA\), which corresponds to \(F_\mathrm {z}\approx 37.4{\text { nN}}\). The reason for this change is the lateral rearrangement of the interacting atoms of the deformable body. Figure 3 shows the displacement vectors of the substrate’s surface atoms calculated from the atoms’ positions at two indentation depths of \(4.3\, \AA\) and \(4.4\, \AA\).

3.1 Hertz Solution

The simulated contact deviates from the Hertz contact theory in different ways: (1) the surfaces are not continuous, (2) although the contact is investigated within the elastic deformation regime, elasticity is not isotropic, (3) the contact is not frictionless due to the inevitable roughness at the atomic scale, and (4) a finite-range repulsion, as opposed to a hard-wall interaction, describes the interaction between the bodies. Nevertheless, it can be argued that the contacts of the atomistic simulations and continuum theories could be compared, if their stress distributions would go through the same filtering procedure [11].

The Hertz stress distribution has a form of \(\sigma (r)=\sigma _0(1-(r/r_\mathrm {c})^2)^{0.5}\), where \(r_\mathrm {c}\) is the contact radius, and \(\sigma _0\) is the maximum compressive stress. Correspondingly, the contact radius and maximum contact stress are

respectively. Figure 4 shows the maximum stress of the Hertz theory for the investigated contacts. Moreover, following Hertz contact theory, the elastic contact modulus \(E^*\) can be found as follows:

The contact elastic modulus can be estimated via \(E^*=E/(1-\nu ^2)=28.57\,{\text { GPa}}\), with \(E=26\,{\text { GPa}}\) and \(\nu =0.30\) for the simulated material [12]; however, it has already been discussed that, assuming the applicability of Hertz theory at the atomic scale, \(E^*\) is not a constant, but varies with the indenter’s roughness, radius of curvature, indentation depth, and the governing interacting energy between the tip and the deformable body [8]. Figure 5 shows the calculated \(E^*\) from Eq. 3 for both the investigated contacts. As is expected, the results show that the estimated values are not constant: both start at a low value, and increase with \(F_\mathrm {z}\), albeit with different slopes. The \(E^*\) of the smooth indenter increases for the whole range of the elastic contact, while the rough indenter’s remains close to the bulk value. Appendix 1 shows that the samples’ thickness values were large enough to not affect the estimated values of \(E^*\).

3.2 Filtering the Stress Distributions

In order to compare the stress distributions of the investigated contacts calculated for different numbers of bins N (further discussed in Sect. 2.4), i.e., \(\sigma (N)\), the distributions are smoothened with a low-pass filter. Herein, following the suggestion in [11], we use a Gaussian filter of the form

where \(\varvec{r}^2=(x-x_\mathrm {m})^2+(y-y_\mathrm {m})^2\), with \(x_\mathrm {m}\) and \(y_\mathrm {m}\) being the coordinates of the center of the xy plane, which are set to zero in this investigation, \(\varDelta\) is the width of the filter, and \(A=1/2\pi \varDelta ^2\) ensures that \(\int G(\varDelta ,\varvec{r}) d\varvec{r}=1\). Hereafter, we denote this filter as \(G(\varDelta )\). The filtered distributions \(\sigma (N,\varDelta )\) are calculated via

where \(\mathcal {F}\) and \(\mathcal {F}^{-1}\) denote the Fourier and its inverse transform, respectively. In this investigation, we define \(\varDelta\) as a function of the nearest neighbor distance, i.e., we employ \(\varDelta (p)=pd_\mathrm {NN}\), where p is a dimensionless prefactor; we apply different values of p between 1 and 6 with an interval of 0.5. The nearest neighbor distance can be obtained as \(d_\mathrm {NN}={\text {a}}_0\sqrt{2}/2\approx 3.9516\, \AA\) for the simulated material. It should be noted that the force–displacement curves of the two indentation processes have no intersection in the elastic deformation regime (see Fig. 2), meaning that there is no state in both processes where their corresponding Hertz’s stress distributions can be directly compared with each other; therefore, we present the results of this section for the state of the contacts prior to the first force drop at \(F_\mathrm {z}\approx 55\,{\text { nN}}\), to illustrate how the filtering method reduces the deviations between the results of the atomistic simulation and the Hertz solution.

Figure 6 shows the filtered stress distributions for \(\sigma (N\le 32)\) and \(p=1\) for both contacts. The results show that the filtered distributions of both contacts are quite similar for these small values of N.

Choosing a value for N is rather arbitrary, although it seems to be natural to define N by enforcing \(\lambda =1\), i.e., the area of each bin is equal to the projected area of an individual atom; however, the filtered stress distribution would not change for \(\lambda (N)<1\); see Appendix 2. Therefore, it is wise to select an arbitrarily large value of N, e.g., 128 as in this investigation.

In order to compare the theoretical stress distributions with the ones obtained from the atomistic simulations, they should all be processed through the same filter. Figure 7 compares the filtered stress distributions of both contacts and their corresponding Hertzian ones for different values of \(\varDelta\). The results show that a filter with a resolution of \(\varDelta =5d_\mathrm {NN}\approx 2{\text { nm}}\) smears out the stress distributions such that the contacts become indistinguishable.

The filtered stress distributions of the a smooth and b rough contacts with \(N=128\) in comparison with the corresponding filtered Hertz solutions. Different widths of \(\varDelta (p)=pd_\mathrm {NN}\) are employed in the filters. The gray dotted lines indicate the respective reference abscissae for the shifted distributions

3.3 Interacting Area

Prior to the force drop, the projections of the contact stress distributions (indicating the interacting area) for \(N\le 32\) are found to be almost identical for both contacts. The results are reported in Appendix 3 and show that at \(N=32\) the estimated interacting area becomes localized and circular. Once a value of \(N=72\) is employed, at which \(\lambda (N)=1\), the differences between the interacting areas of the two systems can be easily noticed, as shown in Fig. 8. The interacting bins of the smooth indenter are neighbors, and follow the crystallography pattern of the contacting bodies, while the rough tip results in randomly distributed interacting bins.

The estimated interacting area for a smooth and b rough contacts with \(N=72\). The solid red lines are the contact lines estimated from Hertz theory (Eq. 1) (Color figure online)

Figure 9 shows a comparison between the interacting area as a function of \(F_\mathrm {z}\) for selected values of N. Moreover, it reports the results of two other methods: prediction of Hertz contact mechanics (\(A_\mathrm {Hertz}=\pi R\delta _\mathrm {ind}\)) and estimation of the real interacting area. For the latter, the interacting atoms at each indentation depth are counted and denoted \(T_\mathrm {int}\), and the real interacting area is estimated via \(A_\mathrm {int,real}=T_\mathrm {int}A_\mathrm {a,Ca}\) [9]. The results show that, with increasing N and consequently decreasing bins’ sizes, the estimated interacting areas become smaller. Moreover, \(A_{N=72}\) is found to be close to \(A_\mathrm {int,real}\) at low values of \(F_\mathrm {z}\). The deviations between these two values could be related to the differences between the real shape of the contact and its projection [9]: for the smooth indenter, the deviation could be simply due to the curved shape of the contact, while severe deviations could be expected for the rough tip. Therefore, as soon as the real shape of the interacting area starts to deviate from its projection on the 2D binned space, these methods result in different estimations.

Comparing the results of \(A_{N=72}\) with \(A_\mathrm {Hertz}\) shows that the interacting area for the smooth indenter is close to \(A_\mathrm {Hertz}\) at the beginning of the indentation process, i.e., \(F_\mathrm {z}\le 17{\text { nN}}\) (\(\delta _\mathrm {ind}\le 2.5\, \AA\)), and the Hertz prediction gradually underestimates the contact area. For the rough contact, however, Hertz theory overestimates the interacting area \(A_{N=72}\) for the entire process.

The figure shows the gradient of the filtered stress distributions with different values of p for the (a–c) smooth and (d–f) rough contacts prior to the force drop. (See Fig. 8 for comparison.) The gradient is colored from blue to yellow for its minimum (\(\approx 0\)) and maximum, respectively. The red plus signs and black dots refer to the identified local stress maxima and points on the maximum gradient lines, respectively. The red lines are the identified contact lines, which are the convex hull of the identified points on the maximum gradient lines (Color figure online)

4 How Does Filtering Affect the Estimated Contact Area?

Once the stress distributions are filtered, no sharp border can be simply identified as the contact line; however, in order to use the filtered distributions for estimation of the contact area, it is necessary to define contact. Considering that the filtered distributions are differentiable, let us assume that the contact line is along their maximum gradient. Figure 10 shows the contact lines for both contacts prior to the force drop at \(F_\mathrm {z}\approx 55{\text { nN}}\). The results show that the estimated contact lines for most of the contacts are more or less circular. Note that, for some cases (insets e and f), a number of local stress maxima were identified; however, it can be noticed that not all of the local maxima could be identified using the employed method (Sect. 2.5). This post-processing is performed on the entire indentation process of both atomistic simulations and their corresponding Hertz solutions. Then, the projected contact areas (\(A_\mathrm {pc}\)) are estimated as the enclosed area inside the identified contact lines.

The dashed lines are the estimated projected contact areas (\(A_\mathrm {pc}\)) as functions of the applied p for the a smooth and b rough tips. The thick black lines indicate that value of p at which \(A_\mathrm {pc}\) has its minimum value. The selected data points (a–h) refer to the corresponding insets of Fig. 10

Figure 11 shows the estimated values of \(A_\mathrm {pc}\) for the atomistic simulations at different contact forces as functions of p. The first noticeable finding of this figure is some large initial contact areas obtained from the filtered stress distributions. This is due to our method of defining contact area using the filtered data: the estimated contact area of an individual atom becomes increasingly larger as a wider filter is applied for smoothing the stress distribution. Moreover, the results show two general trends: (1) for low contact forces, the estimated \(A_\mathrm {pc}\) increases with p, and (2) for high contact forces, the estimated \(A_\mathrm {pc}\) decreases to a minimum followed by an increase, by increasing p. The reason for the decrease in \(A_\mathrm {pc}\) is that the small values of p preserve the non-uniformity of the stress distribution, which is a consequence of the inevitable surface roughness at the atomic scale. Increasing p smears out the effects of the surface roughness; thus, the identified contact area becomes more circular, and results in a smaller \(A_\mathrm {pc}\). Further increasing p, however, makes the stress distribution spread out more, resulting in larger \(A_\mathrm {pc}\). In order to compare the estimated values of \(A_\mathrm {pc}\) with the Hertz solution, Fig. 12 shows \(A_\mathrm {pc}\) as functions of contact force. The results show that, for either indenter, a value of p can be found at any given contact force resulting in a projected contact area comparable with the Hertz solution. Through this comparison, the values of p resulting in the closest value of the two solutions are identified, which are reported in Fig. 13. It can be seen that a unique value of p cannot be found to accurately apply to the whole range of the simulated process. See Appendix 4 for further discussions on applying a single value of p.

The estimated \(A_\mathrm {pc}\) via the filtered stress distributions as functions of \(F_\mathrm {z}\) for the a smooth and b rough tips. The lines and symbols correspond to the results obtained from Hertz solutions and atomistic simulations, respectively, with (blue colored dashed line, ×) for p set 1, (red colored dashed dotted line, +) for p set 2, and (solid line, open square) for the original data, i.e., the data of Hertz and \(A_{N=72}\) before filtering (see Fig. 9) (Color figure online)

Figure 14 shows the values of \(A_\mathrm {pc}\) estimated using two sets of p: (1) those at which the corresponding estimated contact area has its minimum value, i.e., the black lines in Fig. 11, and (2) those reported in Fig. 13. The first finding of this figure is that the filters diminish the deviations between the estimated projected contact areas obtained from the atomistic simulation \(A_\mathrm {pc,sim}\) and Hertz theory \(A_\mathrm {pc,H}\). Moreover, the results show that the estimated contact behavior depends on the applied filter. Using the first set of p, the values of \(A_\mathrm {pc}\) for the smooth tip obtained from both the atomistic simulation and Hertz theory are lower than the original estimations for the entire indentation process. For the rough tip, however, \(A_\mathrm {pc,sim}\) is lower than \(A_\mathrm {pc,H}\) before the initiation of the lateral rearrangement of the substrate’s atoms (\(F_\mathrm {z}\approx 37.4{\text { nN}}\)) and becomes higher than \(A_\mathrm {pc,H}\) at larger indentation forces. Applying the second set of p, the values of \(A_\mathrm {pc,sim}\) are either identical to or higher than \(A_\mathrm {pc,H}\) for the entire process. Moreover, the deviations between \(A_\mathrm {pc,sim}\) and \(A_\mathrm {pc,H}\) become significant only for the rough contact for indentation forces larger than \(F_\mathrm {z}\approx 37.4{\text { nN}}\). Furthermore, as is expected, the values of \(A_\mathrm {pc}\) are in good agreement with the Hertz solutions; however, in comparison with \(A_{N=72}\), the filtering method results in under- and overestimations of \(A_\mathrm {pc}\) for the smooth and rough indenters, respectively.

The results reveal an important possible feature of the filtering method. Differentiating between the interacting and contacting atoms leads to defining a corresponding contact area \(A_\mathrm {c}\) smaller than the interacting one \(A_\mathrm {int}\) [5, 8]; the validity of this approach has been shown for studying atomistic rough surfaces [6]. For the current studied rough contact, however, the behavior is partly (p set 1) or entirely (p set 2) reversed, i.e., \(A_\mathrm {c}\) is found to be larger than \(A_\mathrm {int}\). This physically unjustifiable artefact is a consequence of the applied filter, and, perhaps, our definition of a contact line.

Furthermore, it should be noted that, while the first set of p can be identified by varying the width of the filter, the preparation of the second set requires a priori knowledge of a reference, e.g., the Hertz solution as in the current study, which can be obtained using indentation test measurements. Note that, although \(A_{N=72}\) can be used as the reference as well, this solution is not directly accessible from an experimental test. This means that, in practice, this solution is not available for calibrating the filter’s width. The presented results of the Hertz model in Fig. 14, both the original and the filtered ones, are based on the Hertz stress field established from \(r_\mathrm {c}\) and \(\sigma _\mathrm {0}\) estimated via Eqs. 1 and 2, respectively; therefore, they require the values of R and \(\delta _\mathrm {ind}\) in advance. Considering the goal of this work, i.e., investigating the applicability of the filtering method, the results which were dependent on some already known data serve solely for validating purposes.

5 Accounting for Roughness

Another way of studying the rough contact is to consider the area of the local contact patches \(\widetilde{A}_\mathrm {pc}\) (see Fig. 15), and estimating \(A_\mathrm {pc}=\sum \widetilde{A}_\mathrm {pc}\). Figure 16 compares the estimated \(A_\mathrm {pc}\) of the rough contact (dashed lines) and \(A_{N=72}\). The results show that, with a relatively narrow filter width of \(\varDelta =1.5\,d_\mathrm {NN}\), the estimated contact area is in good agreement with the benchmark \(A_{N=72}\), up to \(F_\mathrm {z}\approx 37.4{\text { nN}}\) where the lateral movements of the contacting atoms begin. It should be noted that, in the calculation of \(\sum \widetilde{A}_\mathrm {pc}\), the intersected areas are treated by merging them into one contact patch, if the distances between the corresponding local maxima are found to be smaller than closest approach between their identified maximum gradient lines.

The identified contact lines of the local contact patches for the rough contact, using different values of p of a 1 and b 1.5. The red lines are the identified contact lines around any of the identified local maxima. Further details are presented in the caption of Fig. 10 (Color figure online)

The values of the interacting area \(A_{N=72}\) (open square) and \(A_\mathrm {pc}\) estimated via \(\sum \widetilde{A}_\mathrm {pc}\) using different values of p (dashed lines) and Eq. 6 (solid line)

Considering the surface roughness of the contact, the contact area is estimated using the following analytical expression for \(A_\mathrm {pc}\) of a Hertzian tip with small-scale roughness [20]:

with

where \(\overline{g}\) is the root-mean-square gradient of the surface roughness estimated to be \(\sim 0.7\) for the studied rough contact after removing the global curvature of the indenter [21], and \(\kappa \approx 1.6\) [22]. Figure 16 shows the solutions of Eq. 6 (solid line), resulting in values of \(A_\mathrm {pc}\) close to \(A_{N=72}\) for the entire indentation process.

6 Conclusions

In this paper, the idea of applying Gaussian filters on atomistic contact stress fields for smearing out the effects of surface roughness is investigated. Through a binning procedure, the interacting areas for each contact are estimated; comparing the results with the corresponding solutions of Hertz theory shows that the model under- and overestimates the interacting areas for the smooth and rough contacts, respectively. Furthermore, the stress distributions of the atomistic simulations and analytical solutions are locally averaged by applying Gaussian filters with different widths (\(\varDelta\)), and the contact line is defined as the line of maximum gradient of the stress distribution surrounding the contact patch.

The results of this study show that the filtering method improves the correlations between \(A_\mathrm {pc}\) of the atomistic simulation and Hertz theory within the range of elastic deformation for both contacts, albeit with different accuracies depending on the worked filter (Figs. 14, 20). Although the choice of \(\varDelta\) is rather arbitrary (Sect. 3.2), the effect of varying its value on the estimated \(A_\mathrm {pc}\) shows that the applied filter should have a varying width; however, defining the correct range of \(\varDelta\) is problematic. Our suggestion for identifying \(\varDelta\) via finding the minimum of \(A_\mathrm {pc}\) as a function of the filter’s width does not result in accurate estimations of \(A_\mathrm {pc}\) for both contacts and for the entire indentation process. On the other hand, identifying a set of p using a reference, e.g., the Hertz model, requires the assumption of applicability of that reference at the atomic scale. Our presented results show that either of these approaches for identifying the filter’s width leads to deviations between the estimated values of \(A_\mathrm {pc}\) from the filtered stress distributions and those obtained directly from the atomistic simulations, without the possibility of determining a validity range. Therefore, while the filtering process reduces the deviations between the behavior of a non-adhesive atomistic contact and the corresponding Hertz solution, it does not validate the assumption of the applicability of the Hertz model for such a contact, especially for the rough case.

Furthermore, by taking surface roughness into consideration, we define \(A_\mathrm {pc}\) to be the sum of the contact area of local patches, i.e., \(\sum \widetilde{A}_\mathrm {pc}\). By comparing the results with the benchmark \(A_{N=72}\), a filter with \(\varDelta =1.5d_\mathrm {NN}\) is identified for its accurate estimations of the projected contact area, prior to the lateral rearrangements of the surface atoms. Finally, our results with a model for rough Hertzian tips (Eq. 6) suggest that, instead of filtering the contact’s pressure distribution, selecting an appropriate model or theory for the relevant physics may yield more accurate solutions.

References

Luan, B., Robbins, M.O.: The breakdown of continuum models for mechanical contacts. Nature 435(7044), 929–932 (2005)

Luan, B., Robbins, M.O.: Contact of single asperities with varying adhesion: comparing continuum mechanics to atomistic simulations. Phys. Rev. E 74(2), 26111 (2006)

Mo, Y., Turner, K.T., Szlufarska, I.: Friction laws at the nanoscale. Nature 457(7233), 1116–1119 (2009)

Mo, Y., Szlufarska, I.: Roughness picture of friction in dry nanoscale contacts. Phys. Rev. B 81(3), 35405 (2010)

Solhjoo, S., Vakis, A.I.: Continuum mechanics at the atomic scale: insights into non-adhesive contacts using molecular dynamics simulations. J. Appl. Phys. 120(21), 215102 (2016)

Müser, M.H., Dapp, W.B., Bugnicourt, R., Sainsot, P., Lesaffre, N., Lubrecht, T.A., Persson, B.N.J., Harris, K., Bennett, A., Schulze, K., Rohde, S., Ifju, P., Sawyer, W.G., Angelini, T., Esfahani, H.A., Kadkhodaei, M., Akbarzadeh, S., Wu, J.-J., Vorlaufer, G., Vernes, A., Solhjoo, S., Vakis, A.I., Jackson, R.L., Xu, Y., Streator, J., Rostami, A., Dini, D., Medina, S., Carbone, G., Bottiglione, F., Afferrante, L., Monti, J., Pastewka, L., Robbins, M.O., Greenwood, J.A.: Meeting the contact-mechanics challenge. Tribol. Lett. 65(4), 118 (2017)

Solhjoo, S., Vakis, A.I.: Single asperity nanocontacts: comparison between molecular dynamics simulations and continuum mechanics models. Comput. Mater. Sci. 99, 209–220 (2015)

Solhjoo, S.: Nanotribology Investigations with Classical Molecular Dynamics. University of Groningen, Groningen (2017)

Solhjoo, S., Vakis, A.I.: Definition and detection of contact in atomistic simulations. Comput. Mater. Sci. 109, 172–182 (2015)

Jacobs, T.D.B., Martini, A.: Measuring and understanding contact area at the nanoscale: a review. Appl. Mech. Rev. 69(6), 060802 (2017)

Müser, M.H.: Elasticity does not necessarily break down in nanoscale contacts. Tribol. Lett. 67(2), 57 (2019)

Sheng, H.W., Kramer, M.J., Cadien, A., Fujita, T., Chen, M.W.: Highly optimized embedded-atom-method potentials for fourteen fcc metals. Phys. Rev. B 83(13), 134118 (2011)

Hirel, P.: Atomsk: a tool for manipulating and converting atomic data files. Comput. Phys. Commun. 197, 212–219 (2015)

Solhjoo, S., Vakis, A.I.: Surface roughness of gold substrates at the nanoscale: an atomistic simulation study. Tribol. Int. 115, 165–178 (2017)

Daw, M.S., Baskes, M.I.: Embedded-atom method—derivation and application to impurities, surfaces, and other defects in metals. Phys. Rev. B 29(12), 6443–6453 (1984)

Jones, J.E.: On the determination of molecular fields II. From the equation of state of a gas. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A 106(738), 463–477 (1924)

Shu, Z., Davies, G.J.: Calculation of the lennard-jones n-m potential-energy parameters for metals. Phys. Status Solidi A-Appl. Res. 78(2), 595–605 (1983)

Plimpton, S.: Fast parallel algorithms for short-range molecular dynamics. J. Comput. Phys. 117(1), 1–19 (1995)

Polak, E., Ribiere, G.: Note sur la convergence de méthodes de directions conjuguées. Revue Francaise D Informatique De Recherche Operationnelle 3(16), 35–43 (1969)

Müser, M.H.: On the contact area of nominally flat hertzian contacts. Tribol. Lett. 64(1), 14 (2016)

Solhjoo, S., Halbertsma, P.J., Veldhuis, M., Toljaga, R., Pei, Y., Vakis, A.I.: Effects of loading conditions on free surface roughening of AISI 420 martensitic stainless steel. J. Mater. Process. Technol. (2019). in press

Hyun, S., Pei, L., Molinari, J.-F., Robbins, M.O.: Finite-element analysis of contact between elastic self-affine surfaces. Phys. Rev. E 70(2), 026117 (2004)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Displacement Fields

Figure 17 shows the magnitude of the displacement fields of the deformed samples, normalized by the slip distance \(d_\mathrm {NN}\), along the line of \(y=L_\mathrm {y}/2\), where the samples deform the most. It shows that, in either case, the elastic stress field is well confined within the sample, and is not (measurably) affected by the applied boundary conditions.

Appendix 2: On the Selection of N

The bin’s size should be small enough so that making it smaller does not affect the filtered stress distributions. Figure 18 shows \(\sigma (N,\varDelta )\) for both systems with different values of N; it shows that the filtered stress distributions are independent of the selected N for \(N\ge 72\), at which \(\lambda =1\).

Appendix 3: Contact Stress Distributions for \(N\le 32\)

Figure 19 shows the identified contacting bins for the smooth and rough contacts, prior to the force drop, i.e., at \(F_\mathrm {z,interact}\approx 55{\text { nN}}\). For \(N\le 8\) the results are identical, and deviations can be noted for larger values of N.

Appendix 4: \(A_\mathrm {pc}\) for Constant Values of p

Figure 20a shows the contact with the smooth tip: for all cases, the estimated contact areas obtained from the atomistic simulations \(A_\mathrm {c,Sim}\) and Hertz theory \(A_\mathrm {c,H}\) agree up to a certain indentation depth, and then they deviate by \(A_\mathrm {c,Sim}\) exhibiting values larger than \(A_\mathrm {c,H}\). Moreover, the results show that enlarging the filter’s width has two effects: (1) the values of \(A_\mathrm {c,Sim}\) and \(A_\mathrm {c,H}\) are close for larger indentation depths, and (2) the deviations between the estimated contact area from the two methods become smaller. The same general trend can be seen for the rough contact (Figure 20b) for \(p=2.5\) and 5, although the deviations are more pronounced than the corresponding trends of the smooth contact. Moreover, the filter with \(p=1\) results in \(A_\mathrm {c,Sim}\) being smaller than the corresponding \(A_\mathrm {c,H}\) for the whole range of the indentation depth. The estimated contact area for the rough contact with \(p=1\) is smaller than both the estimated interacting area and the corresponding Hertz solution, showing no advantage over the calculated interacting areas for comparison with the continuum theory.

The estimated contact area via the original and filtered stress distributions as a function of \(\delta _\mathrm {int}\) for the a smooth and b rough tips. The lines (solid line, red colored dashed line, blue colored dashed dotted line, green colored dashed dotted line) and symbols (open square, open diamond, open triangle, open circle) correspond to the results obtained from Hertz solutions and atomistic simulations, respectively. Note that the results labeled as “original” are the data of Hertz and \(A_{N=72}\) before filtering (see Fig. 9) (Color figure online)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Solhjoo, S., Müser, M.H. & Vakis, A.I. Nanocontacts and Gaussian Filters. Tribol Lett 67, 94 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11249-019-1209-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11249-019-1209-0