Abstract

I argue for an account of semantic paradox that requires minimal logical revision. I first consider a phenomenon that is common to the paradoxes of definability, Russell’s paradox and the Liar. The phenomenon—which I call Repetition—is this: given a paradoxical expression, we can go on to produce a semantically unproblematic expression composed of the very same words. I argue that Kripke’s and Field’s theories of truth make heavy weather of Repetition, and suggest a simpler contextual account. I go on to outline a ‘singularity’ theory of semantical predicates in the spirit of remarks of Gödel. According to this theory, ‘denotes’, ‘extension’ and ‘true’ are context-sensitive expression that apply almost everywhere on a given occasion of use, except for certain singular points. I then turn to revenge paradoxes, and argue that even the dialetheist is subject to revenge. I then examine how the singularity theory responds to revenge.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Kripke, in Martin (1984), p. 80

See Field (2008).

As Field puts it: “If we think of a determinately operator as attaching to a truth predicate to yield a predicate of “strong truth”, we can think of the theory as providing an account of hierarchy of “stronger and stronger truth predicates”. But unlike most approaches that allow a hierarchy of “truth predicates”, no infinite hierarchy of metalanguages is required.” (Field 2008, p. 140).

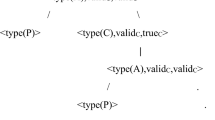

To illustrate the point, consider a simple hierarchical view, where truth is stratified into levels. Suppose we adopt such a view. Given a liar sentence

(A) (A) is not trueα,

we suppose that ‘trueα’ is the truth predicate for a language L (‘trueα’ applies exactly to the true sentences of L), and this predicate is expressible in a metalanguage M for L, but not in L itself. We can say (A) is not trueα—if it were trueα, it would be assessable by the trueα-schema, and contradiction would follow. But our assessment of (A) as not trueα does not lead back to contradiction, because we take it that our repetition of (A), along with (A), are sentences of M that are to be assessed not by the trueα-schema, but by the schema appropriate for sentences of M. Let this be the trueα+1 schema, applying to exactly the true sentences of M, and expressible not in M but in a further metalanguage. Then both (A) and our repetition will be trueα+1, since (A) is not a sentence of L, and so not a true sentence of L—that is, (A) is not trueα.

Heim (1988).

A context can also be non-explicitly reflective with respect to an expression. I’ll turn to this a little later.

There isn’t space to present the formal theory in detail here. But we can see in outline how things go. The primary representation of (R) indicates that (R) is to be assessed by the reflective truthrL-schema. Call the resulting truth value the primary value of (R). The primary value of (R) will depend on the only member of (R)’s determination set, namely (L). Since the primary representation of (L) repeats on the infinite branch of (R)’s primary tree, (L) is identified as a singularity of ‘trueL’. And so (L) is not trueL, just as (R) says. So we can reflectively establish the value true for (R). (R)’s primary value is true (that is, truerL).

It is perhaps worth noting that the primary representation of (R) is a secondary representation of (L).

Compare Kripke’s claim that the ‘level’ of an ordinary statement involving truth depends on the empirical facts about the statement, and should not be assigned in advance by the speaker: “in some sense a statement should be allowed to seek its own level” (Kripke 1975), in Martin (1984, p. 60. See pp. 60–61 and 71–72). Setting aside the notion of level (since the singularity approach does not stratify the truth predicate), the case of U is broadly in line with Kripke’s claim. The extension of ‘true’ in U depends on features of the context (the empirical facts about U spelled out by the semantic network U generates in its context of use) that need not be known in advance by the speaker.

It is sometimes objected that hierarchical versions of contextualism about truth have no systematic way to attribute levels to a given utterance. This isn’t a complaint that can be leveled against the singularity theory. According to the singularity theory, truth isn’t stratified—rather, it’s a matter of identifying the singularities of a given occurrence of ‘true’. And for that, we need only the notion of the reflective status of a context—either given explicitly as a feature of the context, or given via the semantic connections displayed in primary trees. As we’ve seen, even if Max produces the Liar sentence (L), this too is assessed by the truthU-schema. There is no need to exclude (L), or any of Max’s utterances, from the scope of the truthU-schema.

Now, since none of Max’s utterances are excluded from the scope of the truthU-schema, your utterance U is equivalent to the infinite conjunction:

if Max says “S1” then S1, and if Max says “S2” then S2, and ….

Your use of ‘true’ in U allows you to express a generalization that it would otherwise take an infinite conjunction to express. Disquotationalists about truth have emphasized the intersubstitutability of “S” and “S is true”, and the expressive role of truth—its role in expressing generalizations that we couldn’t otherwise express. The singularity theory accommodates the expressive role of truth.

But there are limits to the intersubstitutability principle. Consider again the Liar sentence (L) again, represented as

(L) (L) is not trueL.

Consider (L) and ‘(L) is trueL’. Consider a reflective evaluation of these. For example, consider the evaluation of these by the truerL-schema. (L) is truerL. But ‘(L) is trueL’ is falserL—it’s not the case that (L) is trueL (it fails to have trueL conditions). So here the intersubstitutability principle fails. This is related to a point made in Dummett (1959), p. 145.

So we need to restrict the truth-schema. Once we have the notion of a singularity on board, we can provide a minimally restricted truth-schema for an occurrence of ‘true’ tied to context α:

If ‘S’ is not a singularity of ‘trueα’, then ‘S’ is trueα iff S.

Singularities aside, intersubstitutability holds. Similarly for denotation and extension.

See Priest (2006), especially Chapter 20, and footnote 12.

There is more to say about the singularity theory and revenge that I can say here—see Chapter 12 of Simmons (2013) for an extended discussion.

This is a convenient way to talk—but it should be understood that to say, for example, that (L) is true in (R)’s context of use is a shorthand way of saying that it’s true when assessed by the schema associated with (R)’s context of use.

Recanati (2002), p. 312.

Jason Stanley takes certain contextualist accounts of truth, such as that in Burge (1979), to hold that ‘true’ is a narrow indexical, and he argues that this claim is put into doubt by the observation that the vast number of cases of unobvious context dependence do not involve narrow indexicality—see Stanley (2000). But the singularity account does not take ‘true’, denotes’ or ‘extension’ to be narrow indexicals.

References

Allerton DJ (1978) The notion of “givenness”, 44th edn. Lingua, Amsterdam, pp 133–168

Burge T (1979) Semantical paradox. J Philos 76:169–98, reprinted with a postscript in Martin 1984, 83–117

Chafe W (1976) Givenness, contrastiveness, definiteness, subjects, topics, and point of view. In: Li C (ed) Subject and topic. Academic Press, New York, pp 25–55

Dummett M (1959) Truth. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society 141–62

Field H (2008) Saving truth from paradox. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Gödel K (1944) ‘Russell’s mathematical logic’, In: Schilpp PA

Grosz BJ (1977) The representation and use of focus in a system for understanding dialogs, Proceedings of the Fifth International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Los Altos, Morgan Kaufmann 1977, 67–76. Reprinted in Grosz BJ, Sparck Jones K, Webber BL (eds), Readings in natural language processing, Los Altos, Morgan Kaufmann 1986

Grosz B, Sidner C (1986) Attention, intention, and the structure of discourse. Comput Linguist 12:175–204

Halliday MAK (1967) Notes on transitivity and theme in English: part 2. J Linguist 3:199–244

Heim I (1988) The semantics of definite and indefinite noun phrases. Garland Publishing, New York and London

Kripke S (1975) Outline of a Theory of Truth. J Philos 72:690–716; reprinted in Martin RL (ed) 1984, 53–81

Lewis D (1979) Scorekeeping in a language game. J Philos Logic 8:339–359; reprinted in Lewis 1983, 233–249

Lewis D (1980) Index, context, and content, In: Kanger S, Ohman S (eds), Philosophy and grammar Dordrecht, Reidel; reprinted in Lewis 1998, 21–44

Martin RL (ed) (1984) Recent essays on truth and the liar paradox. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Priest G (2006) In contradiction: a study of the transconsistent (expanded edition). Oxford University Press, Oxford

Recanati F (2002) Unarticulated constituents. Linguist Philos 25:299–345

Schilpp PA (ed) (1944) The philosophy of Bertrand Russell. La Salle, Open Court, pp 123–153

Simmons K (1993) Universality and the Liar: an essay on truth and the diagonal argument. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Simmons K (1994) Paradoxes of denotation. Philos Stud 76:71–104

Simmons K (2000) Sets, classes and extensions: a singularity approach to Russell’s paradox. Philos Stud 100:109–149

Simmons K (2013) Paradox: reference, predication, truth, ms

Stalnaker R (1975) Indicative Conditionals. Philosophia 5:269–286; reprinted in Stalnaker (1999), 63–77

Stalnaker R (1978) Assertion. In: Cole P (ed), Syntax and semantics, vol. 9: pragmatics, New York, New York University Press 197–213; reprinted in Stalnaker 1999, 78–95

Stalnaker R (1988) On the representation of context. J Logic Lang Inform 7:3–19

Stalnaker R (1999) Context and content: essays on intentionality in speech and in thought. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Stanley J (2000) Context and logical form. Linguist Philos 23:391–434

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Simmons, K. Paradox, Repetition, Revenge. Topoi 34, 121–131 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11245-013-9225-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11245-013-9225-4