Abstract

The addition of elements other than Al in the framework structures of zeotype materials gives the opportunity to tune the acidity of the zeotype and thus might expand the possibilities in the field of acid-catalyzed reactions. Here, we have synthesized silicalite (MFI) with and without Fe and/or Al in the framework structure. To understand the mechanism of the removal of the structure directing agent (SDA) from the as synthesized samples we combine X-ray diffraction, nitrogen sorption and in situ IR spectroscopy experiments. IR spectroscopy is also used to examine the acid species with and without NH3 as probe molecule. Furthermore, NO adsorption is performed to characterize the different metal species. The results of the IR experiments during calcination of the SDA suggest that the SDA first loses contact with the internal surface of the zeotype and then at higher temperature is oxidized to CO2. The IR spectra of the zeotype samples in the H+-form show that the sample containing both Fe and Al shows a broader and less intense peak at 3620 cm−1 indicating the presence of two distinct Brønsted acid sites, one associated to Fe and one to Al. The IR experiments after NH3 adsorption confirm these results and thus the following series of increasing acidity could be outlined: 0 = pure silicalite < Fe-silicalite < Fe/Al-silicalite < Al-silicalite. Finally, the IR experiments after NO adsorption shows the presence of nitrates in the Fe-containing samples suggesting the formation of extra framework Fe species.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Zeolites are aluminosilicate materials widely used in industry for the unique property, among the others, of solid acids [1]. The capability of zeolites to donate protons in a confined environment makes these microporous materials excellent catalysts for many acid-catalyzed reactions. One of the most outstanding processes in petroleum refinery which exploits the acidity of zeolites is the fluid catalytic cracking (FCC) of petroleum crude oils, where the long straight paraffin chains are converted into more valuable products [2]. Moreover, zeolites are also promising catalysts for the valorization of biomass for replacing crude oil with alternative feedstocks [3]. Recent studies suggest that the acidity of zeolites could be used as descriptor for the conversions of methane-to-methanol [4, 5] and of methanol-to-DME [6]. In particular, a lower acidity of the catalyst is believed to promote methanol desorption in the direct conversion of methane to methanol [4, 5], whilst a higher acidity of the catalyst is believed to promote the formation of DME from methanol dehydration [6].

It is thus clear that tuning the acidity of zeolites is of foremost relevance. The crystal lattice of zeolites is based on the SiO44− and AlO45− tetrahedrons [7]. Thus, a counter cation is needed to maintain charge neutrality. When the counter cation is a proton, the Si–O(H)–Al site is denoted as Brønsted acid site (BAS). The acidity of a zeolite is thus related to the amount of Al in the framework in the sense that one can tune the number of BASs by adjusting the Si/Al ratio used during the zeolite synthesis. However, for a given type of framework structure, the strength of the BASs may not be influenced by the Si/Al ratio. This can be easily shown, for example, by NH3 adsorption experiments. In fact, the amount of NH3 adsorbed on a zeolite surface will change according to the Si/Al ratio, but the adsorption strength will not change [8]. In this perspective, elements other than Al (e.g. Fe, Ga, In, B etc.) have been incorporated in framework position to control the acidity strength [9,10,11,12]. For the sake of clarity, the term zeotypes will be used in this work to address these microporous materials showing typical zeolites structures but having various elements in framework positions. Furthermore, the term BAS will be used also for metals other than Al.

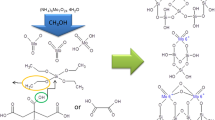

In zeolites synthesis, the main ingredients consist of silica and alumina precursors and a structure directing agent (SDA) which directs the crystallization [13]. Several synthesis methods are available to obtain the final zeolite, but synthesis through the sol–gel process and further hydrothermal crystallization is the most commonly used method. In a standard synthesis procedure, the silica precursor is mixed with the metal precursor and the SDA in aqueous medium. The so obtained gel is crystallized in autoclave and the product is washed, filtered and dried. The SDA is then removed by calcination and the acid form of the zeolite is obtained by ammonium exchange and further calcination. The substitution of Si with Al in the framework structure is facile due to the similar electronic configuration of the two elements, resulting in highly stable structures and nor or minor Al leakage from the framework [14]. The substitution of Si with elements other than Al in the synthesis gel prior to crystallization requires instead more attentions and often leads to less stable structures. For example, when adding Fe during synthesis the gel needs to be acidic to prevent the precipitation of iron hydroxides and then the pH needs to be increased to the basic conditions necessary to promote crystallization. Furthermore, the SDA must be added after the silicate-metal network has formed and low molecular weight silica sources are usually preferred to promote the metal incorporation [10, 15, 16].

The present study aims to give a fundamental understanding of Fe and Al containing zeotypes with MFI type of framework structure, where the metals are added prior to crystallization. We examine with in situ IR spectroscopy the entire process from the removal of the SDA from the framework to the activation of the zeotype into its acid form. The acidity of the synthesized zeotypes is investigated with regards to the metal added during synthesis. In particular, we show by means of IR spectroscopy and NH3 adsorption that the Fe-BASs are weaker in acidity than the Al-BASs. Furthermore, NO adsorption is performed to characterize the different metal species, suggesting that not all Fe is incorporated in the framework and thus that some Fe species are present in extra framework position. We also suggest some parallelisms between the results obtained with nitrogen adsorption and IR spectroscopy that, to our knowledge, have not been discussed in the open literature. We speculate that the electronegativity of the metal substituting Si in framework position might influence in the same way both the interactions between the adsorbate and the zeotype surface, and the acidity of the BASs.

2 Materials and Methods

Samples of pure (S), Fe-(FS), Al-(AS) and Fe- and Al-(FAS) silicalite with the MFI type of framework structure were prepared according to the method by Szotak et al. [17]. The chemicals used for the synthesis were: tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS, reagent grade, 98%, Sigma Aldrich) as silica source, iron nitrate (Fe(NO3)3·9H2O, 98+% metal basis, Alfa Aesar) and sodium aluminate (Technical, anhydrous, Sigma Aldrich) as metal precursors and tetrapropylammonium hydroxide (TPAOH, 1.0 M Lsg. in water, Sigma-Aldrich) as SDA. Oxalic acid (98%, Sigma-Aldrich) and sodium hydroxide (pellets, 98%, Alfa Aesar) were used to adjust the pH value. The calculated molar ratios of the metals contained in each sample are shown in Table 1. The calculated molar ratio Si:TPA+:H2O = 1:0.300:24.86 was kept constant in all syntheses.

For all samples, TEOS was first hydrolyzed for 24 h at 60 °C in water and oxalic acid (pH 2). The metal precursors were dissolved in water for 5 h (for the Fe/Al-silicalite sample, two solutions were prepared) and added to the TEOS containing solution. The solution was kept at pH 2 in order to prevent precipitation of metal hydroxide species. After 4 h of stirring, a 20 wt% solution of TPAOH was added drop-wise under vigorous stirring and then the pH was adjusted with an 1 M NaOH solution to the basic conditions necessary to promote crystallization (pH 11). It is noteworthy that the TPAOH should be added once the metal-silicate network is formed as the free amines present might form complexes with the metal species of the metal precursor [15]. These gels were heated in unstirred autoclaves (0.2 L, Parr Instrument Company) for 5 days at 170 °C. The so obtained powder sample was washed, filtered and freeze-dried overnight. In order to remove the SDA and to obtain the Na+-form of the zeotypes, the as synthesized samples were calcined at 500 °C for 5 h (5 °C min−1) in air. The Na+-zeotype samples were then ion-exchanged twice at 60 °C for 24 h with ammonium nitrate (EMPLURA®, Sigma-Aldrich), followed by washing, filtration and freeze-drying overnight. The H+-form of the zeotype was obtained by calcination at 500 °C for 1 h (10 °C min−1) in air. The NH4+-exchange and the second calcination were not performed for the pure silicalite sample, S. Additionally, Fe was added to 0.5 g of calcined silicalite sample by incipient wetness impregnation. The Fe source and the Si/Fe ratio used for the impregnation were the same of the ones used for the synthesis of the Fe-silicalite sample. The so obtained wet sample powder was freeze-dried over night to remove the solvent and calcined for 2 h at 500 °C (starting from room temperature with a heating rate of 5 °C min−1).

The X-ray diffractograms of the SDA-containing samples, the Na+-form of the zeotype samples and the Fe-impregnated silicalite sample were recorded with a Bruker XRD D8 advanced instrument with monochromatic CuKα radiation scanning from 5 to 55° (step size 0.029°, dwell time 1 s). The nitrogen isotherms were measured by a Micrometrics Tristar 3000 instrument at − 196 °C after degassing in N2 at 220 °C for 5 h. The in situ IR spectra were recorded using a VERTEX 70 spectrometer (Bruker) in the diffuse reflectance mode (diffuse reflectance infrared Fourier transform spectroscopy, DRIFTS) with a mercury cadmium telluride (MCT) detector (bandwidth 600-12000 cm−1) cooled with liquid nitrogen. A praying mantis component and a high-temperature stainless steel reaction chamber (Harrick Scientific Products, Inc.) were used to achieve the diffuse reflectance mode and to control the sample temperature, respectively. The spectra were recorded between 800 and 4000 cm−1 with a resolution of 1 cm−1. The sample scan time used was 64 s, but for the backgrounds the scan time used was 200 s to obtain more accurate reference spectra. Furthermore, the sample signal gain was times 2 and the scanner frequency was of 20 kHz. In order to obtain uniform powder size distribution and thus to minimize the signal to noise ratio of the spectra and avoid possible structural dependencies of the spectra, the sample was sieved and the fragment between 40 and 80 µm was used. A KBr powder bed was used underneath each sample bed in the sample holder of the spectrometer to minimize the amount of sample used for the experiments. The IR spectral series collected during the calcination of the SDA-containing samples and during the activation of the zeotype samples from the NH4+- to the H+-form were recorded in 10% O2 in Ar from 200 to 500 °C with a linear heating rate of 5 and 10 °C min−1, respectively. In order to investigate the acidity and to characterize the metal species of the samples, spectra were collected at room temperature in Ar after saturating for 30 min the calcined silicalite sample and the zeotype samples in the H+-form with 400 ppm NH3 in Ar and with 450 ppm NO in Ar, respectively. Before the NH3 and the NO adsorption experiments a pretreatment in 10% O2 in Ar for 1 h at 500 °C (10 °C min−1 temperature ramp) was performed to remove any possible contaminations from the surface.

3 Results and Discussion

3.1 Structural Characterization

The MFI type of framework structure of all samples is confirmed by XRD [18]. In Fig. 1a, the X-ray diffractograms of the as synthesized and calcined silicalite sample are shown (the X-ray diffractograms associated to the metal containing samples are shown in Online Resources 1 and 2). The elimination of the SDA by calcination leads to the disappearance of the diffraction peaks associated to the organic molecule and the variation of some peak intensities. The position of the other diffraction peaks remains unchanged indicating the thermal stability of the framework structure. The X-ray diffractograms of the Fe-silicalite, Al-silicalite and Fe/Al-silicalite samples confirm the MFI structure and do not show any extra peaks associated to metal particles, neither any peak shifts compared to the X-ray diffractogram of the silicalite sample. This means that the amount of metals is likely too low to be detected by XRD both if some particles are formed and if Fe and Al are incorporated in the framework structure.

The N2 sorption experiments on the calcined silicalite sample and the Fe-silicalite, Al-silicalite and Fe/Al-silicalite samples in the Na+-form reveal that the addition of different metals during synthesis leads to different values of both BET surface area and micropore volumes, although all values are reasonable for the MFI type of framework structure [19] (see Table 2). Studies on iron incorporation in the MFI framework have shown that the metal tends to migrate from framework to extra framework position during calcination [17]. The fact that the Fe-silicalite sample shows the lowest BET surface area and micropore volume might be due to the presence of iron species in extra framework position, meaning that not all Fe used in the starting synthesis gel has been incorporated in the structure. Moreover, the incorporation of Al in the structure is facile due to the similar electronic configurations of Si and Al and generates the well-known ZSM-5 zeolites. Thus, it is not surprising that the Al-silicalite sample shows the highest BET surface area and micropore volume, indicating that a higher percentage of metal used in the starting gel has been incorporated in the structure. This is also supported by the fact that the Fe/Al-silicalite sample shows intermediate values of surface area and micropore volume between the Fe-silicalite and the Al-silicalite samples. The calcined silicalite sample shows lower BET surface area and micropore volume than the Al-silicalite sample but higher values than (or similar to) the Fe containing samples. This might be due to the presence of defects on the internal surface of the pure silicalite and/or to the presence of minor amounts of amorphous silica. Nevertheless, any amorphous silica could only be present in particles smaller than and/or in amounts lower than the XRD detection limit.

The microporous structure is further confirmed by the hysteresis loop of the N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms. As an example, the isotherms associated to the calcined silicalite sample are shown in Fig. 1b. These isotherms are typical for the type IV isotherms [20] showing the first transition to liquid-like adsorbate at around 0.2 of relative pressure and saturation at around 120 cm3/g. More insights about the metal incorporation in the MFI structure can be deducted by considering the N2 adsorption isotherm of each sample (Fig. 2, note that the x axis is here in logarithmic scale). The desorption isotherms are not shown in these graphs as they would not give additional information to the cause and they would make the trends more difficult to observe. It has previously been found that the electrostatic interactions between the adsorbate, i.e. the quadrupole N2 molecules, and the adsorbent, i.e. the zeolite surface, in ZSM-5 zeolites influence the shape of the adsorption isotherms [21, 22]. The first transition in the adsorption isotherms, associated to capillary condensation effects, is typical for several microporous materials [23]. ZSM-5 zeolites with high Si/Al ratios show at high relative pressures a second transition from liquid- to solid-like state of the adsorbate [21]. The increase of the amount of Al leads to the shift of this second transition towards higher relative pressures, until its extinction for very low Si/Al ratios. Furthermore, it has been shown that this behavior seems to not be influenced by the counter-cation, rather only by the Si/Al ratio. In the present study, the calcined silicalite sample and the Fe-silicalite sample in the Na+-form show clearer plateaus and sharper second transition bumps in the adsorption isotherms, whilst the Al-silicalite sample in the Na+-form shows a smoother transition over a broader range of relative pressures and the Fe/Al-silicalite sample in the Na+-form shows intermediate behavior. This might be due to the fact that different metals, although in the same molar amounts, can influence the shape of the isotherms in a similar way as the Si/Al ratio does. In this perspective, it seems that Fe-incorporation in the MFI framework leads to weaker adsorbate–adsorbent electrostatic interactions. The parallelisms that these interactions might have with the acidity of the samples will be further discussed.

3.2 DRIFTS

3.2.1 Removal of the SDA

In order to investigate the mechanism of the removal of the SDA and the activation process of the metal-containing zeotypes, the calcination of the as synthesized powder of all samples and the calcination of the NH4+-form of the metal containing zeotype samples were followed by DRIFTS, respectively. As example, the IR spectra of the as synthesized silicalite sample recorded during calcination from 250 to 500 °C are shown in Fig. 3a (the other samples show similar trends). Three series of absorption peaks can be identified: a doublet at 2300–2400 cm−1, a group of sharp peaks at around 2800–3100 cm−1 and a singlet at 3740 cm−1. The doublet at 2300–2400 cm−1 indicates the formation of CO2 and thus the ultimate oxidation of the propyl chains of the TPA+ molecules. This doublet appears at 350 °C and increases in intensity with increasing temperature, meaning that more SDA is combusted when the temperature in the reaction cell is increased. A more careful investigation should be done for the absorption peaks around 2800–3100 cm−1. In literature, peaks around 3000 cm−1 are mostly assigned to C–H stretching vibrations of various species [24]. In particular, negative peaks in this region are associated to the removal of the organic template by calcination of materials synthesized by means of structure directing agents [25]. In Fig. 3a, the positive absorption peaks around 2800–3100 cm−1 suggest formation of C–H bonds. This, however, is unlikely as it would represent addition of the structure directing agent. To make the interpretation of these peaks clearer, one may consider the spectrum after calcination at 30 °C in Ar, shown in Fig. 3b by the grey curve (note that the background of this spectrum is the same of the spectral series of Fig. 3a). After calcination, most of the organic template is eliminated and thus distinct negative peaks in the C–H stretching vibration region are expected to appear. Indeed, the negative peaks at 2980, 2944 and 2880 cm−1 are assigned to C–H stretching vibrations of the propyl chains of the TPA+ molecule [24] and thus they clearly show the removal of the SDA. The fact that in Fig. 3a the elimination of the TPA+ molecules while increasing the temperature is not clearly visible might be due to the rather complex oxidation process of the organic molecule located at the channel intersections of the framework. Indeed, in the as synthesized sample at room temperature the SDA and the internal surface of the zeotype interact via Van der Waals interactions [26, 27]. By increasing the temperature in an oxidizing environment, the SDA first loses contact with the framework and then at higher temperatures it oxidizes, ultimately to CO2. Thus, we believe that at the early stages of the calcination process, i.e. at intermediate temperatures and short times, there might be competition between these two phenomena which could lead to misinterpret the nature of the peaks in Fig. 3a. The positive absorption peak at 3740 cm−1 is assigned to terminal (isolated) silanol groups (Si–OH) typical for silica based materials. This peak appears and evolves concurrently with the 2800–3100 cm−1 peaks, meaning that the silanol groups become IR visible as soon as the TPA+ molecules lose contact with the internal surface of the zeotype. Thus, this is in line with the fact that the TPA+ molecules interact via Van der Waals interactions with the surface of the zeotype.

Background subtracted IR spectra of a the as synthesized silicalite sample recorded during calcination in 10% O2/Ar from 250 to 500 °C and b the as synthesized silicalite sample recorded at 500 °C in 10% O2/Ar and the calcined silicalite sample recorded at room temperature in Ar (red and grey curves, respectively). The background was taken at 200 °C in 10% O2/Ar

3.2.2 Activation of the Zeotypes and Acidity of the BASs

The IR spectra recorded during the activation of the metal-containing samples from the NH4+- to H+-form show generally two series of broad negative absorption peaks at 3100–2800 cm−1 and 3370 cm−1, and two sharp positive absorption peaks at higher wavenumbers. As example, the spectra collected during calcination of the Fe-silicalite sample in the NH4+-form are shown in Fig. 4a, but the corresponding spectra of the Al-silicalite and Fe/Al-silicalite samples show similar behaviors. The negative peaks in the 3100–2800 cm−1 region are again assigned to C–H stretching vibrations and thus are related to the elimination of the TPA+ molecules, suggesting that not all the SDA was removed during the first calcination. Nevertheless, the intensity of these peaks is relatively low indicating that only a minor amount of the SDA remained in the framework after the first calcination. The broad negative absorption peak at 3370 cm−1 is assigned to N–H stretching vibrations [24] and thus is associated to the loss of N–H species due to the activation of the zeotype samples from the NH4+- to the H+-form. The sharp positive peaks at 3630 and 3740 cm−1 are assigned to acid –OH [9] and terminal silanol groups, respectively. It is noteworthy that the N–H peak evolves together with the acid –OH peak, i.e. increasing the temperature the N–H peak decreases in intensity whilst the acid –OH peak increases, suggesting that these –OH groups belong to the zeotype Brønsted acid sites (Si–O(H)–Fe), BASs.

a Background subtracted IR spectra of the Fe-silicalite sample in the NH4+-form recorded during calcination in 10% O2/Ar from 250 to 500 °C. The background was taken at 200 °C in 10% O2/Ar; b IR spectra recorded at room temperature in Ar of the calcined silicalite sample and the Fe-silicalite, the Al-silicalite and the Fe/Al-silicalite samples in the H+-form

In order to investigate the acidity of the BASs, spectra of the metal containing zeotypes samples in the H+-form were collected after the O2 pretreatment in Ar at room temperature (see Fig. 4b). For comparison, also the spectrum of the calcined silicalite sample is shown. All samples show the absorption peak assigned to the terminal silanol groups at 3740 cm−1, whilst the position of the BASs peak depends on the metal added in the synthesis gel. Indeed, the Fe-silicalite, the Al-silicalite and the Fe/Al-silicalite samples show the BASs peak at 3630, 3610 and 3620 cm−1, respectively, whilst the calcined silicalite sample shows no peaks in this region. The addiction of metals other than Si in framework position leads to electric charges in the zeolites structure, which are balanced by counter ions (in this case H+). The electronegativity of the metal added in place of Si influences the nature of the –OH groups of the BAS, in particular more electronegative elements added in framework positions leads to more covalent –OH groups which is translated in the IR spectra in a shift of the BASs peak to higher wavenumbers. This in turn means weaker acid site and thus the following series of increasing acidity can be derived: 0 = silicalite < Fe-silicalite < Fe/Al-silicalite < Al-silicalite. Furthermore, the shape and the intensity of the absorption peaks assigned to the BASs is also reasonable. Indeed, that the Fe/Al-silicalite sample shows a broader and less intense peak is likely due to the fact that this sample presents two different BASs (one for Fe and one for Al) which overlap in the IR spectrum. It is noteworthy that also the spectrum of the Fe-impregnated silicalite sample, where Fe is only in extra framework position, shows no acid –OH peaks (see Online Resources 2). Although the N2 sorption measurements and NO adsorption suggest that some Fe is in extra framework position in the Fe-silicalite sample, this fact confirms that the peak at 3630 cm−1 is due to the BASs generated by Fe in framework position in place of Si.

It is in the spectra of Fig. 4b that we notice some parallelisms with the N2 adsorption isotherms in Fig. 2. Indeed, the lower acidity of the Fe-BASs, suggested by a peak positioned at higher wavenumbers in the IR spectrum, is reflected by a weaker interaction with the quadrupole N2 molecule, suggested by a clearer second transition bump from liquid- to solid-like state of the adsorbate in the adsorption isotherm. This is further confirmed by the extreme case of the metal-free silicalite sample, which shows no BASs in the IR spectrum and a distinct two-transition adsorption isotherm. We speculate that, relying both phenomena on the different electronegativities of Fe and Al, it should not be surprising to find parallelisms even between two measurements quite distant from each other. On the one hand, these parallelisms are of remarkable relevance as the open literature hitherto does not provide a full study of these. On the other hand, we stress that we are far from alone to suggest that adsorption measurements could be a method to determine the different acidity strength of the zeotypes BASs.

3.2.3 NH3 Adsorption

To further investigate the acidity of the zeotype samples, IR spectra were collected after NH3 adsorption on all samples (see Fig. 5a). For comparison, the IR spectrum recorded for the calcined silicalite sample is also shown. The spectral series can be divided in three regions: the NH4+-chemisorption and Lewis acid sites region (1400–2000 cm−1), the N–H stretching region (2000–3500 cm−1) and the –OH stretching region (3500–4000 cm−1). In the first region, the absorption peaks at 1488 [28], 1745 [29, 30] and 1946 cm−1 [30] show similar intensities among all samples and they are assigned to NH4+ adsorbed on BASs. The peak at 1592 cm−1, assigned to NH3 adsorbed on Lewis sites [29], is more pronounced in the spectrum of the Al-silicalite sample and almost disappears in the spectrum of the Fe-silicalite sample. This might suggest that the presence of Fe inhibits the formation of Lewis acid sites. Nevertheless, the intensity of this peak is generally low and thus further investigations should be conducted to confirm this suggestion. In the second region, the broad and intense peak at 2733 cm−1 and the shoulder at 2187 cm−1 are assigned to weakly bounded NH3 in the zeotype samples whilst the peaks at 3294 and 3392 cm−1 are assigned to symmetric and asymmetric N–H stretching vibrations of NH4+ adsorbed on BASs [31]. These peaks in the second region are all in common between the samples. In the third region, it is evident the adsorption of NH3 on the terminal silanol groups and on the BASs. The negative peaks are here assigned to the suppression of the O–H stretching vibrations of the terminal silanol and the BASs in favor of the NH3 adsorption.

a Background subtracted IR spectra recorded at room temperature in Ar after NH3 adsorption on the calcined silicalite sample and the Fe-silicalite, Al-silicalite and Fe/Al-silicalite samples in the H+-form, from the bottom to the top of the graph. The backgrounds were taken before NH3 adsorption in Ar at room temperature. b IR spectra recorded in Ar at room temperature before and after NH3 adsorption on the Fe-silicalite sample in the H+-form

The raw spectra after NH3 adsorption give more insights about the interaction between the probe molecule and the adsorbent sites. In Fig. 5b, the IR spectra before and after NH3 adsorption on the Fe-silicalite sample in the H+-form are shown as example, but the corresponding spectra of the Al-silicalite and the Fe/Al-silicalite samples in the H+-form show similar behaviors. After NH3 adsorption, the terminal silanol peak (3740 cm−1) and the BAS peak (3630 cm−1) partially and completely disappears, respectively. This means that some Si–OH remain intact whilst the BASs are totally substituted by Si–O(–NH4+)–Fe species, confirming the stronger adsorption strength of the BASs compared to terminal Si–OH.

3.2.4 NO Adsorption

NO adsorption on the zeotype samples in the H+-form was also performed to characterize the metal species added during the synthesis. For comparison, the experiment was also performed on the calcined silicalite sample. In Fig. 6 the background subtracted IR spectra collected after NO adsorption clearly show that the Fe/Al-silicalite sample has features in common with both the Fe-silicalite and the Al-silicalite samples, but the latter two do not show any similarities between each other in the selected wavenumber regions. In the region between 1700 and 2000 cm−1, no samples show any absorption peaks (the entire spectral series are shown in the Online Resource 3). NO adsorption on Fe-containing zeolites and zeotypes has been extensively investigated, mostly for the promising catalytic properties of these materials for deNOx-SCR, and thus a detailed database is now available for assigning peak [12, 30,31,32,33]. Nevertheless, if some vibrational bands have been unanimously assigned in literature, others are still under debate. It seems well established that the peak at 2135 cm−1 is assigned to NO+ occupying cationic position in the microporous structure [31], and thus is related to the acid strength of the zeotype. That this peak can only be observed in the Al containing samples might be due to the higher acidity of the Al-BASs, i.e. to the fact that these BASs donate protons easier than the Fe-BASs in favor of the positively charged NO. This is supported by the fact that the Fe-containing samples show a clear doublet at lower wavenumbers, indicating the preferential NO adsorption on these sites rather than the cationic position. The peaks at 1615 and 1580 cm−1 have previously been assigned to bridging and bidentate nitrates, respectively [33]. If the presence of nitrates indicates formation of Fe species capable of oxidizing NO to NO3−, the nature of this Fe species does not seem clear. Indeed, in literature several peaks have been assigned to NO adsorbed on different Fe species (oxides, particles, oligomers etc.), but in the present study none of these peaks have been found [12, 34,35,36]. Nevertheless, it can be excluded the presence of Fe in ionic exchange position as the relative adsorption peaks have been encountered in literature at higher wavenumbers (ca. 1880–1870 cm−1 [31]), where instead no sample show any IR absorption peaks.

Background subtracted IR spectra recorded at room temperature in Ar after NO adsorption on the calcined silicalite sample and the Fe-silicalite, Al-silicalite and Fe/Al-silicalite in the H+-form. The entire spectral series is shown in Online Resources 3. The backgrounds were taken before each experiment at room temperature in Ar

4 Concluding Remarks

The BET surface area and the micropore volume obtained by N2 adsorption are the highest for the Al-silicalite sample and the lowest for the Fe-silicalite sample, suggesting the presence of extra framework Fe species in the latter sample. This might be due to the lower stability of Fe in the framework which might lead to extraction of Fe from the zeotype framework during calcination. Furthermore, the adsorption isotherms for the pure silicalite and the Fe-containing samples show a more distinct bump at high relative pressures. For ZSM-5 zeolites, this bump has previously been suggested to be due to the transition from liquid- to solid-like state of the probe molecule, where the position and intensity of the bump is influenced by the Si/Al ratio of the zeolite. We suggest that the addition of Fe rather than Al influences the interaction with the probe molecule, and thus the shape of the adsorption isotherms, in the same way as the increase of the Si/Al ratio does.

The IR spectra recorded during the removal of the SDA by calcination show that the absorption peaks associated to the formation of terminal (isolated) silanol groups and to the disappearance of the TPA+ molecules evolve simultaneously. The formation of CO2 due to the combustion of the organic molecule occurs at higher temperatures. This suggests that the TPA+ molecules first lose contact with the internal surface of the zeotype, making the silanol groups IR visible, and then at higher temperature are oxidized to CO2. The decrease of the intensity of the absorption peak assigned to N–H stretching vibrations and the simultaneous increase of the intensity of sharp isolated peaks in the –OH region during calcination of the NH4+-form of the zeotype samples confirm the assignment of the latter peaks to the BASs of the zeotypes. In particular, the peaks at 3630 and 3610 cm−1 are assigned to the Fe- and Al-BASs, respectively. The sample containing both Fe and Al shows a broader and less intense peak at 3620 cm−1 suggesting the presence of two distinct BASs, one associated to Fe and one to Al. NH3 adsorption confirms these results by showing the probe molecule adsorbing preferentially on the BASs. The following acidity series can be outlined: 0 = pure silicalite < Fe-silicalite < Fe/Al-silicalite < Al-silicalite. NO adsorption shows formation of nitrates on the Fe-containing samples suggesting the formation of extra framework Fe species and thus that not all Fe is incorporated in the framework during the synthesis. This, as previously discussed in the results from the N2 adsorption experiments, could be due to the lower Fe stability in the MFI structure.

We also notice the existence of some parallelisms between the results obtained by the N2 adsorption and the IR experiments. When the more electronegative Fe is added in framework position, we observe that the adsorption isotherm shows a clearer second transition and the IR spectrum shows the BASs peak at higher wavenumbers. This can be interpreted as weaker interactions between the zeotype surface and the adsorbate, and weaker acid sites, respectively, which is a direct consequence of the different electronegativity of the metals added in framework positions.

References

Jacobs PA, Flanigen EM, Jansen JC, van Bekkum H (2001) Introduction to zeolite science and practice. Leuven KU, Leuven

Gary JH, Handwerk GE, Kaiser MJ (2001) Petroleum refining: technology and economics, 5th edn. CRC Press, Boca Raton

Ennaert T, Van Aelst J, Dijkmans J et al (2016) Potential and challenges of zeolite chemistry in the catalytic conversion of biomass. Chem Soc Rev 45(3):584–611

Hammond C, Dimitratos N, Lopez-Sanchez JA et al (2013) Aqueous-phase methane oxidation over Fe-MFI zeolites; promotion through isomorphous framework substitution. ACS Catal 3(8):1835–1844

Hammond C, Forde MM, Ab Rahim MH et al (2012) Direct catalytic conversion of methane to methanol in an aqueous medium by using copper-promoted Fe-ZSM-5. Angew Chemie Int Ed 51(21):5129–5133

Yaripour F, Baghaei F, Schmidt I, Perregaard J (2005) Catalytic dehydration of methanol to dimethyl ether (DME) over solid-acid catalysts. Catal Commun 6(2):147–152

Elaine LES, A.Moore E (2005) Solid state chemistry: an introduction. CRC Press, Boca Raton

Lónyi F, Valyon J (2001) On the interpretation of the NH3-TPD patterns of H-ZSM-5 and H-mordenite. Microporous Mesoporous Mater 47(2–3):293–301

Berndt H, Martin A, Kosslick H, Lücke B (1994) Comparison of the acidic properties of ZSM-5 zeolites isomorphously substituted by Ga, In, B and Fe. Microporous Mater 2(3):197–204

Borade RB (1987) Synthesis and characterization of ferrisilicate zeolite of pentasil group. Zeolites 7(5):398–403

Chu CTW, Kuehl GH, Lago RM, Chang CD (1985) Isomorphous substitution in zeolite frameworks. II. Catalytic properties of [B]ZSM-5. J Catal 93(2):451–458

Mul G, Pérez-Ramírez J, Kapteijn F, Moulijn JA (2002) NO adsorption on ex-framework [Fe, X]MFI catalysts: novel IR bands and evaluation of assignments. Catal Lett 80(3–4):129–138

Burton AW, Zones SI (2007) Organic molecules in zeolite synthesis: their preparation and structure-directing effects, vol 168. Elsevier BV, Amsterdam

Maesen T (2007) The zeolite scene-An overview. Stud Surf Sci Catal 168:1–12

Ratnasamy P, Kumar R (1985) Ferrisilicates-A review 1952(6):278–279

Szostak R, Thomas TL (1986) Preparation of ferrisilicate ZSM-5 molecular sieves. J Catal 100(2):555–557

Szostak R, Nair V, Thomas TL (1987) Incorporation and stability of iron in molecular-sieve structures. J Chem Soc Faraday Trans 83(2):487–494

Flanigen EM, Bennett JM, Grose RW et al (1978) Silicalite, a new hydrophobic crystalline silica molecular sieve. Nature 271(5645):512–516

Hudec P, Smieskova A, Zidek Z et al (1998) Adsorption properties of ZSM-5 zeolites. Collect Czech Chem Commun 63(2):141–154

Thommes M, Kaneko K, Neimark AV et al (2015) Physisorption of gases, with special reference to the evaluation of surface area and pore size distribution (IUPAC Technical Report). Pure Appl Chem 87(9–10):1051–1069

Saito A, Foley HC (1995) High-resolution nitrogen and argon adsorption on ZSM-5 zeolites: effects of cation exchange and Si Al ratio. Microporous Mater 3(4–5):543–556

Mailer U, Unger KK (1988) Characterization of porous solid. Elsevier, Amsterdam

Schüth F, Sing KSW, Weitkamp J (2002) Handbook of porous solids, vol. 1. Wiley, Weinheim, pp 1543–1591

Wallace WE (2018) In: Linstrom PJ, Mallard WG (eds) Infrared spectra in NIST chemistry webbook, NIST standard reference database number 69. National Institute of Standards and Technology, Gaithersburg, MD. https://doi.org/10.18434/T4D303

Kondoh E, Segawa K, Watanabe M, Jin L, Zhang L, Baklanov MR (2017) Removal of organic template of mesoporous organosilicate thin films using supercritical carbon dioxide fluids. Jpn J Appl Phys 56(7):5–8

Burkett SL, Davis ME (1995) Mechanism of structure direction in the synthesis of pure-silica zeolites. 2. Hydrophobic hydration and structural specificity. Chem Mater 7(2):1453–1463

Burkett SL, Davis ME (1995) Mechanisms of structure direction in the synthesis of Si-ZSM-5: an investigation by intermolecular 1H-29Si CP MAS NMR. Chem Mater 1:920–928

Shi X, He H, Xie L (2015) The effect of Fe species distribution and acidity of Fe-ZSM-5 on the hydrothermal stability and SO2 and hydrocarbons durability in NH3-SCR reaction. Cuihua Xuebao 36(4):649–656

Lai S, Meng D, Zhan W et al (2015) The promotional role of Ce in Cu/ZSM-5 and in situ surface reaction for selective catalytic reduction of NOx with NH 3. RSC Adv 5(110):90235–90244

Lai S, She Y, Zhan W et al (2016) Performance of Fe-ZSM-5 for selective catalytic reduction of NOx with NH3: Effect of the atmosphere during the preparation of catalysts. J Mol Catal A Chem 424(x):232–240

Shwan S, Adams EC, Jansson J, Skoglundh M (2013) Effect of thermal ageing on the nature of iron species in Fe-BEA. Catal Lett 143(1):43–48

Kustov LM, Kazansky VB, Ratnasamy P (1987) Spectroscopic investigation of iron ions in a novel ferrisilicate pentasil zeolite. Zeolites 7(1):79–83

Hadjiivanov K, Knozinger H, Tsyntsarski B, Dimitrov L (1999) Effect of water on the reduction of NOx with propane on Fe-ZSM-5. An FTIR mechanistic study. Catal Lett 62(x):35–40

Iwasaki M, Yamazaki K, Banno K, Shinjoh H (2008) Characterization of Fe/ZSM-5 DeNOx catalysts prepared by different methods: relationships between active Fe sites and NH3-SCR performance. J Catal 260(2):205–216

Grubert G, Hudson MJ, Joyner RW, Stockenhuber (2000) M. The room temperature, stoichiometric conversion of N2O to adsorbed NO by Fe-MCM-41 and Fe-ZSM-5. J Catal 196(1):126–133

Park SM, Seo G, Yoo YS, Han H-S (2000) IR study on the reduction of NO and NO2 by hydrazine monohydrate over Fe-BEA zeolite. Korean J Chem Eng 27(6):1738–1743

Acknowledgements

This work is financially supported by the Swedish Research Council through the Röntgen-Ångström collaborations “Catalysis on the atomic scale” (No. 349-2011-6491) and “Time-resolved in situ methods for design of catalytic sites within sustainable chemistry” (No. 349-2013-567), the Knut and Alice Wallenberg foundation “Atomistic design of catalysts” (No. 2015.0058), and the Competence Centre for Catalysis, which is hosted by Chalmers University of Technology and financially supported by the Swedish Energy Agency (No. 22490-4) and the member companies AB Volvo, ECAPS AB, Johnson Matthey AB, Preem AB, Scania CV AB, Umicore Denmark ApS and Volvo Car Corporation AB.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Creci, S., Wang, X., Carlsson, PA. et al. Tuned Acidity for Catalytic Reactions: Synthesis and Characterization of Fe- and Al-MFI Zeotypes. Top Catal 62, 689–698 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11244-019-01155-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11244-019-01155-4