Abstract

The coadsorption of porphyrin molecules (TMPyP: tetra(N-methyl-4-pyridyl)-porphyrin), sulfate anions and copper on a Au(111) electrode was investigated by the use of cyclic voltammetry (CV) and in situ electrochemical scanning tunneling microscopy. With decreasing electrode potential the following sequence of surface phases was found: (I) an ordered \(\left( {\sqrt 3 \times \sqrt 7 } \right)R19.1^\circ - {\text{S}}{{\text{O}}_4}^{{2 - }}\) structure on the unreconstructed Au(111)-(1 × 1) surface; (II) a disordered SO42−-layer on the still unreconstructed Au(111)-(1 × 1); (III) a \(\left( {\sqrt 3 \times \sqrt 3 } \right)R30^\circ\) coadsorption structure of 2/3 ML Cu and 1/3 ML SO42−; (IV) a completed 1 ML Cu covered by a layer of mobile, i.e. not imaged, SO42− anions, moreover, a coadsorption layer of disordered porphyrin molecules and still mobile SO42− anions; (V) overpotentially deposited Cu-multilayers terminated by the well known Moiré-type modulated \(\left( {\sqrt 3 \times \sqrt 7 } \right)R19.1^\circ - {\text{S}}{{\text{O}}_4}^{{2 - }}\) structure (similar to bulk Cu(111)) and covered by a dense layer of flat lying TMPyP molecules showing a growing square as well as hexagonally ordered arrangement, and at even more negative potential values and low Cu concentrations in the solution (VI) a pseudomorphic underpotentially deposited Cu-monolayer covered by a \(\left( {\sqrt 3 \times \sqrt 7 } \right)R19.1^\circ - {\text{S}}{{\text{O}}_4}^{{2 - }}\) layer and a dense, ordered porphyrin layer ontop. The formation of the various phases is driven by the potential dependent surface charge density and the resultant electrostatic interaction with the respective ions. A severe imbalance between the copper deposition and desorption current in the CV spectra suggests also the formation of CuTMPyP-metalloporphyrin on the surface which diffuses into the bulk solution.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Following the examples in nature where porphyrin derivatives play a vital role in biochemical processes like chlorophyll in the photosynthesis of plants, like heme of red blood cells in the transport and storage of oxygen, and like vitamin B-12 in the metabolism of creatures, porphyrin based molecules have also found broad application in technology. The modification of the porphyrin core by different functional groups and different metal centres (e.g. Fe, Cu, Co, Mg, Mn, etc.) results in the formation of various porphyrin derivatives which are basic materials for electro-catalysts of reduction and oxidation reactions [1, 2], for drug production [3] and cancer chemotherapy [4], as well as for sensors [5,6,7], solar cells [8], optoelectronic and data storage devices [9], and molecular electronics [10]. Important industrial processes catalysed by porphyrins [11] such as epoxidation, carbonylation, hydroxylation and sulfoxidation [12] are schematically highlighted in Fig. 1.

The efficiency per porphyrin molecule in the respective process, of course, depends on its accessibility, and is, thus, expected optimal if the molecules are spread out as thin films on a supporting surface. In this case the properties of the molecules will also be determined by their immediate environment, i.e. by the interactions with adsorbed molecular neighbours and the influence of the substrate. Both these influences determine the nano-architecture and the functionality of thin deposited films, and have thus been studied in a number of investigations both in ultrahigh vacuum (UHV) and in liquids [13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23]. In these studies the use of single-crystalline substrates helps to reduce “heterogeneous broadening” of both the distribution of the inherent properties of the individual molecules and the detected characteristic signals from them.

Since the more natural environment for the application of functionalized porphyrin molecules are aqueous solutions, investigations of the adsorption of porphyrin molecules at solid–liquid interfaces are particularly important. Moreover, while basic variants of porphyrin molecules are thermally rather stable also during evaporation, functionalized porphyrins with extended ligands may no longer be intact volatile. In this case their deposition can only be done from a liquid phase, e.g. as neutral molecules from a bulk liquid or by spray deposition or electrochemically as cations from solution. This approach is actually also more convenient and economic than vapour deposition, and enables also the investigation of elementary steps of surface reactions in (electro-)catalysis, corrosion, electroplating and -etching, galvanization etc., key processes in modern technology.

In this work we concentrate on the investigation and characterization of electrochemically adsorbed porphyrin layers, namely tetra(N-methyl-4-pyridyl)-porphyrin (TMPyP) in the form of water soluble tosylate—salts, at modified gold surfaces in dilute sulfuric acid solution. Besides the composition and structure of the substrate surface and the chemical nature and concentration of the species in the solution phase the electrochemical approach provides a further control parameter, namely the electric potential of the electrode. The electrode potential not only controls the surface coverage of the involved species according to their charge state, but may also induce electron transfer processes between the surface and the adsorbed molecules, i.e. redox-reactions. These redox processes change the charge state of the adsorbed species and thereby the electrostatic interactions within the adsorbed layer as well as between the adsorbate and the electrode, which is also expected to cause structural changes. Besides the chemical and structural properties of the substrate surface, the electric potential is thus a useful parameter to trigger and study structural phase transitions of molecular layers at metal–electrolyte interfaces [24,25,26,27,28].

Dominant adsorbate–adsorbate interactions will result in a spontaneous self-assembly of the adsorbed species and the formation of ordered 2D (or in the extreme 3D) molecular aggregates [29]. In this case the structure of the molecular adsorbate is not affected by the substrate underneath, but depends only on the properties of the interacting molecules, among others also on their charge state. If, however, the interactions between the adsorbed molecules and the substrate pre-dominate, the sample acts as a template, which may induce the structure of the molecular overlayer, i.e. there is a “symmetry transfer” from the substrate to the adsorbate layer. In reality, the structure of the molecular layer is usually a consequence of a mixture of both, self-assembly and template effect.

In order, to achieve, at given external conditions, the equilibrium structure the relevant interactions must also be reversible, i.e. the molecules must be able to leave a given bonding configuration and form new bonds. This is possible with noncovalent interactions such as electrostatic, van-der-Waals, and π–π interactions as well as hydrogen bonds. Under electrochemical conditions in aqueous electrolytes, besides electrostatic forces, hydrogen bonds may play a particularly important role.

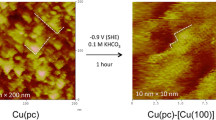

In our model studies we have used an Au(111) single crystal electrode which was modified by underpotential (upd) and overpotential (opd) deposition of copper layers in sulfuric acid solution. Copper and gold, which are often used as working electrodes in electrochemistry, exhibit different chemical properties. Copper is more reactive than noble metals like Au, Ag, and Pt. Gold in the form of bulk samples is chemically rather inert. The potential window of Cu extends to more negative values than that of gold (see Figs. 2, 3, 10) and therefore permits to study phenomena which occur under more reactive/reductive conditions. The choice of copper is also motivated by its significance as “metal of the 21st century” in the production of nanoscale circuitry, namely in the Damascene process of electroplating and on-chip wiring, which is largely controlled by the operation of co-adsorbed organic molecules, so-called accelerators, suppressors, and levellers [30, 31]. The aims of this work are to study the adsorption and ordering of TMPyP as a simple representative of the class of porphyrins on copper layers of different thickness on a Au(111) electrode and to compare the results with those known from bare Au(111) and bulk Cu(111). After a description of the experimental conditions we briefly review (i) the electrochemical redox-behaviour of TMPyP as determined on inert HOPG, (ii) the interfacial electrochemistry of bulk Au(111) and Cu(111) in pure as well as TMPyP containing dilute sulfuric acid, (iii) the modification of the Au(111) electrode surface by underpotential (upd) and overpotential (opd) deposition and co-adsorption of sulfate anions, and then (iv) present the results for adsorbed TMPyP layers on the differently copper-terminated Au(111) surface.

Partial cyclic voltammogram of Au(111) recorded in a 0.1 M H2SO4 solution, scan rate dE/dt = 10 mV/s. HER reflects the hydrogen evolution, the maxima A/A′ and P/P′ are associated with the adsorption/desorption and an order/disorder structural transition of sulfate (\({\text{S}}{{\text{O}}_4}^{{2 - }}\)) on the surface, respectively. The in situ STM images were recorded in the indicated potential range: a STM image 54.2 nm × 54.2 nm of the reconstructed Au(111)-\(\left( {23 \times \sqrt 3 } \right)\) surface taken at a tunnelling current It = 1 nA, a bias voltage Ut = − 450 mV, and an electrode potential E = − 400 mV. b image 8.8 nm × 8.8 nm of the unreconstructed Au(111)-(1 × 1) surface covered with disordered sulfate (It = 46 nA, Ut = − 335 mV, E = − 157 mV); c image 353 nm × 353 nm of Au(111) with two dimensional gold islands formed after the sulfate induced lifting of the surface reconstruction (It = 10 nA, Ut = + 24 mV, E = − 157 m); d image 8.9 nm × 8.9 nm of the \(\left( {\sqrt 3 \times \sqrt 7 } \right)\) sulfate structure on Au(111)-(1 × 1) (It = 3 nA, Ut = − 781 mV, E = 297 mV); e height profile along the white line in f taken after oxidation of the surface; f image 135 nm × 135 nm obtained after surface oxidation (dissolution) and redeposition of Au (It = 1 nA, Ut = 24 mV, E = 10 mV)

Cyclic voltammogram of Cu(111) in 5 mM H2SO4, scan rate dE/dt = 10 mv/s. HER hydrogen evolution reaction, CDR copper dissolution reaction, CRD copper redeposition reaction. a In situ STM image of the adsorbate-free Cu(111) surface at negative potentials (3 nm × 3 nm, It = 30 nA, Ut = − 10 mV, E = − 215 mV). In a wide range between A and R adsorption of a disordered \({\text{S}}{{\text{O}}_4}^{{2 - }}\) layer takes place, which at R transforms into a stable \(\left( {\sqrt 3 \times \sqrt 7 } \right) - {\text{S}}{{\text{O}}_4}^{{2 - }}\) structure with Moiré-type superstructure (dark regions) shown in b 31 nm × 31 nm, It = 1 nA, Ut = 79 mV, E = 140 mV; and c 7.6 nm × 7.6 nm, It = 1 nA, Ut = − 120 mV, E = − 56 mV; d model of the \(\left( {\sqrt 3 \times \sqrt 7 } \right) - {\text{S}}{{\text{O}}_4}^{{2 - }}\) structure (see text). CV and STM data adopted from [42]

Cyclic voltammograms of Au(111) in a 0.1 M H2SO4 + 1 mM CuSO4 solution (CV1), and Au(111) in the 0.1 M H2SO4 + 1 mM CuSO4 + 0.01 mM TMPyP solution (CV2). In CV1 the current maxima correspond to: Ox/Ox′ = dissolution(oxidation)/redeposition of Au, P/P′ = order/disorder phase transition of \({\text{S}}{{\text{O}}_4}^{{2 - }}\) on Au(111), A/A′ = adsorption/desorption of \({\text{S}}{{\text{O}}_4}^{{2 - }}\) on Au(111), S/S′ = desorption/adsorption of 2/3 ML of Cu, M/M′ = desorption/adsorption of 1/3 ML of Cu, B/B′ = desorption/adsorption of Cu multilayers, C = phase transition of \({\text{S}}{{\text{O}}_4}^{{2 - }}\) on 1 ML of Cu with associated adsorption of H2O and/or H3O+. In CV1 the observed sulfate structures are: (I) \(\left( {\sqrt 3 \times \sqrt 7 } \right)\) of \({\text{S}}{{\text{O}}_4}^{{2 - }}\) on Au(111)-(1 × 1), (II) disordered \({\text{S}}{{\text{O}}_4}^{{2 - }}\) on Au(111)-(1 × 1), (III) \({\left( {\sqrt 3 \times \sqrt 3 } \right)_1}\) of \({\text{S}}{{\text{O}}_4}^{{2 - }}\) on 2/3 ML of Cu on Au(111)-(1 × 1), (IV) disordered \({\text{S}}{{\text{O}}_4}^{{2 - }}\) on 1 ML of Cu on Au(111)-(1 × 1), (V) \({\left( {\sqrt 3 \times \sqrt 7 } \right)_M}\) of \({\text{S}}{{\text{O}}_4}^{{2 - }}\) on Moiré Cu multilayers, (VI) \({\left( {\sqrt 3 \times \sqrt 7 } \right)_1}\) of \({\text{S}}{{\text{O}}_4}^{{2 - }}\) on 1 ML of Cu on Au(111)-(1 × 1). CV2 corresponds to the black trace in Fig. 10 and is shown here for direct comparison with CV1 in the TMPyP containing solution. P1 and P2 mark the first two two-electron reduction steps of the adsorbed TMPyP molecules (see Fig. 8 and text)

2 Experimental

The experiments were carried out by the use of an apparatus built at the University of Bonn [32] which combines in situ scanning tunneling microscopy [33] and cyclic voltammetry. The incorporation of both methods in the same electro-chemical cell enables a direct correlation of the CV and EC-STM results. Cyclic voltammograms in different potential windows between the hydrogen evolution and the gold oxidation reaction were scanned in order to identify all adsorption/desorption peaks [34]. The electrochemical cell has a volume of 2.5 ml and is made of Teflon, which is particularly suitable for experiments in strong acid solutions. The experimental four electrode setup consisting of the STM tip, the sample (working electrode), a Pt/PtO (pseudo-)reference electrode, and the counter electrode (Pt) with a bipotentiostat permits the registration of STM images in the liquid environment in potentiostatic, potentiodynamic, as well as quasi-spectroscopic mode [32, 33]. Here we present and discuss STM images taken in potentiostatic and constant tunneling current mode, i.e. during the registration of an STM image the electrode potential is kept constant. Before the measurements the Au(111) sample was electropolished in sulfuric acid solution, and subsequently soaked in hydrochloric acid solution in order to remove oxides from the surface. The surface was then exposed to an oxygen-rich butane-air flame and annealed in order to remove all organic contaminants and to heal defects. During the whole process, in particular during the subsequent cooling down, the sample was kept under a high-purity argon atmosphere [35].

STM tips were prepared by an alternating current etching procedure from a 0.25 mm diameter tungsten wire in 2 M KOH solution. Each tip was rinsed in ultra-pure distilled water and covered by hot polymer glue (Pattex, Germany). In such a way the uncovered apex of the tip was minimized and, hence, any faradaic current flowing through the tip was reduced far below the level of the tunneling current [33, 36].

Cyclic voltammetry measurements were performed by recording of the ion current flowing between the working electrode (sample) and counter electrode as a function of the sample potential determined with respect to the reference electrode (Pt/PtO) using typically a scan rate of 10 mV/s.

1 mM and 0.1 mM CuSO4 solutions in 0.1 M H2SO4 were prepared from ultrapure copper sulfate and sulfuric acid (Merck), as well as Milli-Q distilled water (18.2 MΩ and total organic carbon content (TOC) below 5 ppb). The porphyrin molecules (suprapure, halide-free, Scientific Frontiers) were used without further purification.

3 The Substrates

3.1 Au(111) in Sulfuric Acid

The well prepared Au(111) surface (see Sect. 2) exhibits the well known \(\left( {23 \times \sqrt 3 } \right)\) surface reconstruction as observed under UHV conditions [37, 38] as well as in sulfuric acid solution at very negative potentials, where no specific adsorption of \({\text{S}}{{\text{O}}_4}^{{2 - }}\) anions takes place [39, 40]. Figure 2 displays the relevant low potential part of a cyclic voltammogram of Au(111) in 0.1 M H2SO4 between the limit of the cathodic hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) and the anodic formation of an ordered layer of sulfate anions. The even more anodic part up to the gold oxidation (Ox) is seen in Fig. 4, CV1. Inset (a) in Fig. 2 shows a large scale in situ STM image taken at − 400 mV (vs. Pt/PtO) which clearly exhibits the “herringbone” reconstruction of the Au(111) surface. A potential scan (10 mV/s) towards more positive potentials leads to adsorption (A) of sulfate anions and lifting of the gold surface reconstruction (inset b, c). Since the atomic density of the reconstructed Au(111)-(23×\(\sqrt 3\)) surface is about 4% higher than that of the unreconstructed Au(111)-(1 × 1) surface the lifting of the reconstruction causes a displacement of these excess atoms and their reassembly into small gold islands on the surface (inset c). At this stage the adsorbed SO42− layer is still disordered (inset b). At even more positive potentials, namely at P, a disorder–order phase transition within the SO42− layer takes place [41] and the formation of a long-range ordered \(\left( {\sqrt 3 \times \sqrt 7 } \right) - {\text{S}}{{\text{O}}_4}^{{2 - }}\) structure is observed as shown in inset (d) up to the oxidation reaction of the gold electrode (Ox in CV1, Fig. 4). These processes, sulfate adsorption, lifting of the substrate reconstruction, the disorder–order phase transition of sulfate and the surface oxidation are reversible (see A′, P′, Ox′ in Figs. 2, 4). In particular the (\(23 \times \sqrt 3\)) reconstruction is restored. However, repeated cycling leaves the surface with an increasing amount of defects (inset f in Fig. 2) due to the involved transport of gold atoms in the reconstruction–deconstruction process. These defects are vacancy islands and added islands of Au atoms, which appear after the redeposition of Au from solution (peak Ox′ in CV1 in Fig. 4), as evidenced by the height profile shown in inset (e) of Fig. 2 taken along the white line in inset (f).

The fact, that no ordered sulfate structure was observed in neutral solutions (pH 7), points to the need of hydronium ions (rather than water molecules) to stabilize the \(\left( {\sqrt 3 \times \sqrt 7 } \right) - {\text{S}}{{\text{O}}_4}^{{2 - }}\) adlayer. A model of the \(\left( {\sqrt 3 \times \sqrt 7 } \right)\) structure is shown in Fig. 3d. In turn, in situ infrared (IR) measurements of the ordered sulfate layer in acidic solution support the presence of co-adsorbed hydronium ions [42,43,44].

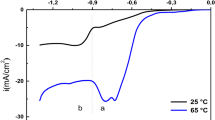

3.2 Cu(111) in Sulfuric Acid

Figure 3 shows the complete cyclic voltammogram of a Cu(111) surface in sulfuric acid solution between the cathodic hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) and the copper dissolution reaction (CDR). In contrast to Au(111) the anion-free Cu(111) surface at very negative potentials is not reconstructed, but shows the regular hexagonal (111)-(1 × 1) atom arrangement (inset a) [45,46,47,48]. With increasing potential \({\text{S}}{{\text{O}}_4}^{{2 - }}\) anions adsorb over a broad potential range, again forming first a disordered layer [42], which at peak R transforms into a \(\left( {\sqrt 3 \times \sqrt 7 } \right) - {\text{S}}{{\text{O}}_4}^{{2 - }}\) structure which, in addition, is superimposed by a long-range ordered Moiré-type superstructure (dark regions in insets b, c). The latter is the consequence of a sulfate induced reconstructive expansion of the first copper layer by about 6% and the resultant mismatch between this expanded first and the regular second Cu layer. As a further consequence of this expansion, i.e. lowering of the atom density of the first copper layer, is the formation of added copper islands on top, which are again covered by the \(\left( {\sqrt 3 \times \sqrt 7 } \right) - {\text{S}}{{\text{O}}_4}^{{2 - }}\) structure and sized in units of the Moiré superstructure (inset b). Thus, while sulfate adsorption lifts the reconstruction of the bare Au(111) surface, adsorption of sulfate on the Cu(111) surface induces a reconstruction. Due to the involved copper mass transport this reconstruction/deconstruction process is strongly kinetically controlled, which explains the enormous “hysteresis” between the reconstruction (R) and sulfate desorption signals in the CV [42, 48]. The double-peak structure of the desorption signal is a consequence of the so-called Frumkin-effect [49], namely the extra negative charge of the adsorbed anion layer enhances the reduction of the protons in solution. The dominant right-hand peak of the \({\text{S}}{{\text{O}}_4}^{{2 - }}\) desorption signal corresponds to a superposition of hydrogen evolution (on the \({\text{S}}{{\text{O}}_4}^{{2 - }}\) covered surface) and \({\text{S}}{{\text{O}}_4}^{{2 - }}\) desorption. Inasmuch as the \({\text{S}}{{\text{O}}_4}^{{2 - }}\) anions desorb with decreasing potential the contribution from the hydrogen evolution reaction decreases, and the left-hand peak represents dominantly \({\text{S}}{{\text{O}}_4}^{{2 - }}\) desorption until hydrogen evolution on the bare Cu(111) surface sets in (HER).

Like on Au(111) the \(\left( {\sqrt 3 \times \sqrt 7 } \right) - {\text{S}}{{\text{O}}_4}^{{2 - }}\) layer is stabilized by co-adsorbed hydronium ions, which in this case could even be resolved by in situ STM. The zig-zag chains of small bright spots in Fig. 3, inset (c) between the adsorbed sulfate anions (big bright spots) are assigned to the co-adsorbed hydronium ions, which may be regarded as 2D hydration “shell” insulating the negatively charged sulfate anions from each other. A model of the \(\left( {\sqrt 3 \times \sqrt 7 } \right) - {\text{S}}{{\text{O}}_4}^{{2 - }}\) structure is shown in inset (d). This ordered (\({\text{S}}{{\text{O}}_4}^{{2 - }}+{{\text{H}}_3}{{\text{O}}^+}\)) co-adsorption layer plays a crucial role in the ordered adsorption of the porphyrin molecules.

3.3 Copper Deposition on Au(111) in Sulfuric Acid

The electrochemical deposition of copper on Au(111) is a well established example for the phenomenon of “underpotential deposition (upd)”, namely the electrodeposition of a metal 1 on an unlike substrate 2 at a potential before the electric equilibrium potential of deposition (dissolution) of metal 1 on (from) itself, i.e. the Nernst potential, is reached [50]. The reason for this underpotential deposition is the extra (chemical) interaction between the two unlike metals, here Cu and Au. Obviously this extra interaction decays quickly once the first layer of copper “screens” the gold substrate underneath, so that the phenomenon of underpotential deposition is largely restricted to just one, possibly two, monolayers of deposit. This, in turn, permits a precise control of the amount or layer thickness of the deposited material.

In the case of Cu-upd on Au(111) in sulfuric acid several stages of Cu growth and co-adsorption of sulfate anions on top have been identified [51,52,53,54]. In Fig. 4, CV1 shows a cyclic voltammogram of Au(111) in 0.1 M H2SO4 solution containing 1 mM CuSO4. Like in Fig. 2 the signals at more positive potentials correspond to the adsorption/desorption (A/A′), the disorder → \(\left( {\sqrt 3 \times \sqrt 7 } \right)\)-order/\(\left( {\sqrt 3 \times \sqrt 7 } \right)\)-order → disorder transition of the \({\text{S}}{{\text{O}}_4}^{{2 - }}\) adlayer (P/P′), and the oxidation/reduction of the gold surface (Ox/Ox′). The first stage of Cu-upd (peak S′) leads to the formation of a co-adsorption layer of 2/3 ML copper and 1/3 ML \({\text{S}}{{\text{O}}_4}^{{2 - }}\) anions. The copper atoms form a pseudomorphic layer on the unreconstructed Au(111) surface with a \(\left( {\sqrt 3 \times \sqrt 3 } \right)\)-net of monoatomic Cu vacancies, which are filled by a \({\text{S}}{{\text{O}}_4}^{{2 - }}\) anion each, giving rise to the \({\left( {\sqrt 3 \times \sqrt 3 } \right)_1}\) structure in the first Cu layer (subscript 1) as seen in Fig. 5a, b. The Au island seen in Fig. 5a, which originates from the lifting of the gold reconstruction, is also covered by this \({\left( {\sqrt 3 \times \sqrt 3 } \right)_1}\) co-adsorption structure, which forms also translational domains (Fig. 5b). A model of this \({\left( {\sqrt 3 \times \sqrt 3 } \right)_1}\) co-adsorption structure is displayed in Fig. 5c.

a, b In situ STM images of the \({\left( {\sqrt 3 \times \sqrt 3 } \right)_1}\) structure of sulfate on 2/3 ML of Cu on Au(111) (region III in CV1, Fig. 4) recorded in the 0.1 M H2SO4 + 1 mM CuSO4 solution. a 28.8 nm × 28.8 nm, It = 1 nA, Ut = − 159 mV, E = − 488 mV (Pt/PtO); b 14.4 nm × 14.4 nm, It=10 nA, Ut = − 85 mV, E = − 496 mV (Pt/PtO); c ball model of the \(\left( {\sqrt 3 \times \sqrt 3 } \right)\)1 structure of \({\text{S}}{{\text{O}}_4}^{{2 - }}\) (top and side view). d, e in situ STM images of the \({\left( {\sqrt 3 \times \sqrt 7 } \right)_1}\) sulfate structure on 1 ML of Cu on Au(111) (region VI in CV1, Fig. 4) recorded in a 0.1 M H2SO4 + 1 mM CuSO4 solution. d 15.3 nm × 15.3 nm, It = 1 nA, Ut = 52 mV, E = − 985 mV (Pt/PtO); e 10.9 nm × 10.9 nm, It = 1 nA, Ut = 26 mV, E = − 903 mV (Pt/PtO); f ball model of the \({\left( {\sqrt 3 \times \sqrt 7 } \right)_1}\) structure of \({\text{S}}{{\text{O}}_4}^{{2 - }}\) (top and side view)

The second stage of Cu-upd (peak M′ in Fig. 4) arises from the additional adsorption of 1/3 ML of copper, displacing the \({\left( {\sqrt 3 \times \sqrt 3 } \right)_1} - {\text{S}}{{\text{O}}_4}^{{2 - }}\) structure from the previous Cu vacancies and thereby forming a complete pseudomorphic copper monolayer (1 ML) on the Au(111) surface [35, 55, 56]. However, no corresponding structure can be seen with STM just below the M′ peak indicating that at this potential the Cu monolayer is covered by a disordered \({\text{S}}{{\text{O}}_4}^{{2 - }}\) anion overlayer. Only at potentials E ≤ − 950 mV (region VI in Fig. 4) the formation of a \({\left( {\sqrt 3 \times \sqrt 7 } \right)_1}\) sulfate structure is observed on the first pseudomorphic Cu monolayer as shown in Fig. 5d, e and sketched in Fig. 5f. This structure is readily expected, because the same sulfate structure is also formed on both the bare Au(111) and bulk Cu(111) as shown in Figs. 2 and 3, and described in Sects. 3.1 and 3.2.. Due to the threefold symmetry of the 1 ML Cu/Au(111) system three sulfate domains (I, II, III) rotated by 120° and separated by domain boundaries are observed (Fig. 5d). In Fig. 5e the \({\left( {\sqrt 3 \times \sqrt 7 } \right)_1}\) arrangement of single sulfate anions within one domain is clearly resolved, as it was also observed on the bare Au(111) at more positive potentials (Fig. 2d). In analogy to Au(111), Cu(111) and Pt(111) [42,43,44, 57,58,59] the formation of this layer is interpreted in terms of a co-adsorption layer with hydronium (H3O+) and/or Zundel (H5O2+, i.e. hydrated hydronium) cations, which form hydrogen bonds between the sulfate anions and thereby stabilize this structure.

In Fig. 6a–c in situ STM images recorded in the opd region, i.e. below the Nernst potential, are presented. These images clearly show regions of different local copper coverage, i.e. different thickness of the copper deposit. In Fig. 6b, besides a large region of the \(\left( {\sqrt 3 \times \sqrt 7 } \right)\)1 structure on the first copper monolayer, a slightly brighter (higher) region with a \(\left( {\sqrt 3 \times \sqrt 3 } \right)\) structure as well as an even higher region at the top of the image is seen. Such higher regions (denoted Moiré in panel a, c) are shown enlarged in Fig. 6a together with the \(\left( {\sqrt 3 \times \sqrt 7 } \right)\)1 and in Fig. 6c together with the \(\left( {\sqrt 3 \times \sqrt 3 } \right)\) structure. From a careful analysis of step heights between the three regions \(\left( {\sqrt 3 \times \sqrt 7 } \right)\)1, \(\left( {\sqrt 3 \times \sqrt 3 } \right)\), and Moiré it has been concluded [35, 55, 56], that (i) the \(\left( {\sqrt 3 \times \sqrt 3 } \right)\) structure in Fig. 6b, c corresponds to a \({\left( {\sqrt 3 \times \sqrt 3 } \right)_2} - {\text{S}}{{\text{O}}_4}^{{2 - }}\) + 2/3 ML copper co-adsorption structure in the second layer (within a region of total local Cu coverage of 5/3 ML), where the \({\text{S}}{{\text{O}}_4}^{{2 - }}\) anions again occupy Cu vacancies like in the \({\left( {\sqrt 3 \times \sqrt 3 } \right)_1}\) structure (at a total coverage of 2/3 ML Cu), and (ii) the higher Moiré-islands have a height of ≥ 5 ML copper. The designation “Moiré” becomes clear when zooming into the surface structure of such thicker deposits as shown in Fig. 6d–f. These higher layers exhibit a similar Moiré structure (Fig. 6e) like on Cu(111) in sulfuric acid as shown in Fig. 3c. Moreover, like on bulk Cu(111) some disordered regions (black arrows in panel d) co-exist with the Moiré-structure and become only slowly ordered with time [42, 48]. Thus, Cu deposits of local coverage ≥ 5 ML in contact with sulfuric acid start to show the same behaviour as bulk Cu(111), namely a slow growth of a Moiré structure, which in addition is superimposed by a \(\left( {\sqrt 3 \times \sqrt 7 } \right)\) mesh of \({\text{S}}{{\text{O}}_4}^{{2 - }}\) anions (Fig. 6f). Two differences, however, are noteworthy, (i) the lattice constants of both the Moiré structure of the Cu multilayers and the superimposed \(\left( {\sqrt 3 \times \sqrt 7 } \right) - {\text{S}}{{\text{O}}_4}^{{2 - }}\) structure approach those on bulk Cu(111) only with increasing film thickness, and (ii) the Cu films show a significant density of screw dislocations (white arrow in Fig. 6d), which are most likely triggered by step defects and the small gold islands at the copper–gold interface as a result of the lifted gold surface reconstruction.

a, c In situ STM images recorded in a 0.1 M H2SO4 + 0.1 mM CuSO4 solution during the continuous overpotential deposition (Idep = − 2.2 µA) of Cu from solution (It = 1 nA, Ut = 21 mV, E = − 953 mV (Pt/PtO)); a 43.2 nm × 43.2 nm; b 28.8 nm × 28.8 nm; c 43.2 nm × 43.2 nm. The images reveal the \({\left( {\sqrt 3 \times \sqrt 7 } \right)_1}\) structure of sulfate on the first pseudomorphic Cu monolayer, the growth of the second Cu layer with the \({\left( {\sqrt 3 \times \sqrt 3 } \right)_2}\) sulfate structure, and the growth of Cu multilayers with a sulfate induced Moiré structure. The arrow indicates a stable reference point. d, f In situ STM images of Cu multilayer deposits on Au(111); d shows different terraces covered largely with a Moiré superstructures. Note also the occurrence of screw dislocation (white arrow) as well as diffuse patches (black arrows) of still disordered sulfate (see text). e, f display close-ups of the \(\left( {\sqrt 3 \times \sqrt 7 } \right) - {\text{S}}{{\text{O}}_4}^{{2 - }}\) structure superimposed by the long-range Moiré structure. Imaging parameters are d 86.4 nm × 86.4 nm, It = 1 nA, Ut = 24 mV, E = − 759 mV; e 43.2 nm × 43.2 nm, It = 1 nA, Ut = 21 mV, E = − 690 mV; f 20 nm × 20 nm, It = 1 nA, Ut = 92 mV, E = − 808 mV. Potentials E determined with respect to the Pt/PtO reference electrode

In summary, the system upd-/opd-Cu/Au(111) in sulfuric acid solution exhibits a great variety of surface structures as sketched in Fig. 7 and thereby offers itself as an interesting substrate to study the surface influence on the adsorption and ordering behavior of organic anions in solution, here TMPyP.

4 Prophyrin Adsorption from Sulfuric Acid Solution

Our motivation for the present study arises from the results obtained for TMPyP adsorption on Cu(111) presented in [23] and in particular in [60], and the lack of such investigations on Cu upd layers.

As mentioned in the introduction porphyrins are also available in the form of water soluble salts which can be used to study their adsorption and structural arrangement at solid–liquid interfaces. In this work we used tetra(N-methyl-4-pyridyl)-porphyrin (TMPyP, inset in Fig. 10) in the form of tetratosylate (CH3–C6H4–SO3−) in sulfuric acid solution. Due to its lower charge and much larger molecular volume, and hence, lower charge density the tosylate anion is not a competitive adsorbate for SO42− anions. In fact, the presence of the tosylate anions in the applied solutions has not detectable influence on neither the cyclic voltammetry nor the in situ STM measurements in this work. The concentration of TMPyP in the solutions is given in the figure captions.

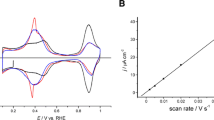

4.1 Electrochemistry of the Porphyrin Molecules

The TMPyP molecules are redox-active. Figure 8 shows cyclic voltammograms of an HOPG (highly oriented pyrolytic graphite) electrode in pure 5 mM H2SO4 (CV1) as well as in 1 mM TMPyP containing 5 mM H2SO4 solution (CV2). Both CVs cover the whole potential range between the cathodic hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) and the oxygen evolution reaction (OER). The presence of the TMPyP molecules leads to a series of clear reduction peaks (P1–P4) as well as a shift of the HER to lower potentials. Since HOPG is “inert” towards specific adsorption of anions these reduction peaks are not disturbed or superimposed by anion adsorption and desorption processes. In the range + 300 to + 900 mV versus RHE the molecules remain in their stable oxidized state and undergo only a pH-dependent acid/base transition:

Direct comparison of cyclic voltammograms CV1–CV7 measured for the various samples indicated next to the respective trace. CV3, CV6 and CV7 reproduce the data from Figs. 2 and 4. Inset a emphasizes the quasi-reversible pair of peaks P1/P1′ for the first two-electron reduction reaction of TMPyP on HOPG measured for different cathodic limits. Inset b accentuates the superposition of the redox-peaks P1/P1′ (see inset a) and the copper dissolution/redeposition current from bulk Cu(111). The designations in CV3, CV6 and CV7 are explained in Figs. 2 and 4 (see also text). Cyclic voltammograms for HOPG (CV1 and CV2) and Cu(111) (CV4 and CV5) were recorded in pure 5 mM H2SO4 and containing 1 mM TMPyP solution, respectively, while those for Au(111) (CV3, CV6, and CV7) in pure 0.1 M H2SO4 and containing 0.1 mM CuSO4 and 0.01 mM TMPyP solution, respectively. Voltammograms CV1, CV2, CV4, and CV5 are adopted from [60]. The full vertical lines mark the potentials of the first two two-electron reduction steps P1 and P2 of the adsorbed TMPyP molecules. The dashed vertical lines mark the cathodic potential limit (red) on bare Au(111) and Cu(111), and the anodic limit (black) on bare Au(111) and bare Cu(111), respectively

Towards lower potentials the molecules are stepwise reduced by electron transfer reactions, e.g.:

which may be associated with the cathodic reduction peaks P1–P4 in Fig. 8 (CV2) [61,62,63,64,65]. Only the first process seems to be reversible (see inset (a) P1/P1′) and is the only which falls into the range of the Cu(111) potential window (see inset b). All other oxidation peaks seem to lie in the range from + 700 to + 2200 mV (RHE) [61, 62], i.e. far outside the potential window of copper, and therefore do not need to be considered further in the present context.

4.2 Porphyrin Adsorption on Au(111) and Cu(111)

The relevant reference system for the behaviour of TMPyP on the copper-modified Au(111) surfaces is obviously the adsorption of TMPyP on Cu(111). Figure 9 displays STM images from two experiments. While panel (a) and (b) refer to TMPyP adsorption on terraces of a Cu(111) surface, which is terminated by a well ordered Moiré/\(\left( {\sqrt 3 \times \sqrt 7 } \right) - {\text{S}}{{\text{O}}_4}^{{2 - }}\)-structure (see Sect. 3.2), panels (c) and (d) demonstrate the adorption behaviour of TMPyP on a highly imperfect Moiré/\(\left( {\sqrt 3 \times \sqrt 7 } \right) - {\text{S}}{{\text{O}}_4}^{{2 - }}\)-structure. A perfect and an imperfect Moiré terminated surface can be prepared by exploiting the slow kinetics of the sulfate induced restructuring of the Cu(111) surface [42, 48]. The faster the potential of the Cu(111) electrode is scanned in positive direction (in the extreme case by a potential jump) beyond peak R in Fig. 3, the less perfect is the resultant sulfate induced Moiré reconstruction. Even though the surface is actually fully covered by sulfate anions in panel (c) only part of it is visibly Moiré-reconstructed. Only on these Moiré-patches the \({\text{S}}{{\text{O}}_4}^{{2 - }}\) anions form a rigid \(\left( {\sqrt 3 \times \sqrt 7 } \right)\) structure; in the diffuse regions in between the sulfate anions are mobile. Panel (a) and a comparison of panels (c) and (d) thus prove that a stable TMPyP structure is only formed on the rigid Moiré/\(\left( {\sqrt 3 \times \sqrt 7 } \right) - {\text{S}}{{\text{O}}_4}^{{2 - }}\) regions. According to the threefold symmetry of the Cu(111) substrate this TMPyP structure occurs in 120° rotated domains (1–3 in panel a). The upper and lower half of panel (b) were registered with “soft” and “drastic” tunneling conditions, respectively [60]. For given tunneling current IT “soft” and “drastic” tunneling conditions are achieved by changing the bias voltage between tip and surface. At high bias voltage the tip is further away from the surface and does not affect the adsorbed molecules, while at low bias voltages the tip comes closer to the surface and may even penetrate into the organic layer, which may lead to a removal of porphyrin species from the surface. This strategy results in an image in which both structures, that of the TMPyP overlayer and the Moiré-structure of the substrate underneath appear side by side, as reflected in Fig. 9b. This enables to extrapolate the lattice of the molecular layer onto the substrate lattice and vice versa, and, thereby, to determine their structural relationship as well as the adsorption sites of the adsorbed species. In the present case the porphyrin molecules form a commensurate overlayer, which is related to the \(\left( {\sqrt 3 \times \sqrt 7 } \right)\) lattice by \(\left( \begin{gathered} {a_{porph}} \hfill \\ {b_{porph}} \hfill \\ \end{gathered} \right)=\left( \begin{gathered} 3\mathop {}\nolimits^{{}} 1 \hfill \\ \bar {2}\mathop {}\nolimits^{{}} 3 \hfill \\ \end{gathered} \right)\left( \begin{gathered} {a_{sulfate}} \hfill \\ {b_{sulfate}} \hfill \\ \end{gathered} \right)\) [60].

In situ STM images of adsorbed TMPyP molecules on a sulfate modified bulk Cu(111) surface in sulfuric acid solution. a Closed TMPyP overlayer on different terraces which are fully Moiré-reconstructed by adsorbed \({\text{S}}{{\text{O}}_4}^{{2 - }}\) anions, 27.4 nm × 27.4 nm, It = 0.1 nA, Ut = 124 mV, E = − 100 mV (RHE); b tip-induced removal of the TMPyP overlayer from the \({\text{S}}{{\text{O}}_4}^{{2 - }}\)/Moiré-reconstructed Cu(111) surface, 9.55 nm × 9.55 nm, It = 0.1 nA, E = − 100 mV (RHE), upper half: Ut = 210 mV (porphyrin imaging), lower half: Ut = 5 mV (\({\text{S}}{{\text{O}}_4}^{{2 - }}\) imaging). The unit cells of TMPyP and \({\text{S}}{{\text{O}}_4}^{{2 - }}\) structure are indicated; c imperfect \({\text{S}}{{\text{O}}_4}^{{2 - }}\)/Moiré-structure on Cu(111) showing regions of still disordered \({\text{S}}{{\text{O}}_4}^{{2 - }}\) (diffuse) and patches of Moiré-reconstruction (55 nm × 55 nm, It = 2 nA, Ut = 46 mV, E = − 144 mV (RHE)); d stabile TMPyP adsorption (bright dots) only on the Moiré-reconstructed patches in c 55 nm × 55 nm, It = 0.1 nA, Ut = 194 mV, E = − 144 mV (RHE). STM images adopted from [60]

4.3 Porphyrin Adsorption on Cu-Modified Au(111)

In this final section we describe the porphyrin adsorption on the Cu-modified Au(111) surface with different sulfate structures on top as presented in Sect. 3.3 and discuss the results in the light of the two reference systems TMPyP/Au(111) and TMPyP/Cu(111) in sulfuric acid solution as delineated in Sect. 4.2.

Figure 10 displays cyclic voltammograms which were recorded in 0.1 M H2SO4 + 0.1 mM CuSO4 + 0.01 mM TMPyP solution by extending the cathodic potential limit to more and more negative values. This reveals the correlation between the cathodic and anodic peaks of the upd/desorption of 2/3 ML of copper (S′/S), of the upd/desorption of the additional 1/3 ML Cu (M′/M) completing the first Cu monolayer, and of opd/desorption (stripping) of Cu multilayers (B′/B). B′ and B increase the more negative potential values are reached, because more Cu is deposited. As already observed in Fig. 4 (CV2) the presence of the TMPyP molecules in the solution leads almost to the disappearance of the maximum S′, and the peak M′ is apparently shifted towards more negative potentials and much more intense than the corresponding desorption peak M (see below). Likewise, the considerable increase of the cathodic peak current in the regime of Cu multilayer deposition (area of peak B′) is much larger than both the mere Cu opd current (compare CV1 and CV2 in Fig. 4) as well as the Cu desorption maximum B. Two effects may contribute to this imbalance of the peak pairs M′/M and B′/B in Fig. 10. On the one hand M′ and B′ are a superposition of two reduction currents, namely from the reduction of Cu2+ cations (Cu upd) and from the reduction of TMPyP cations which undergo the first two two-electron transfer reaction in these regimes (see peaks P1 plus inset (a) and P2 in CV2 of Fig. 8). On the other hand one can also assume that part of the adsorbing Cu is incorporated into TMPyP molecules on the surface forming CuTMPyP which desorbs and transports copper into the bulk solution [66]. Only the rest of copper desorbs during the sweep towards positive potentials and forms peaks B and M. Interestingly, the more negative the cathodic limit is chosen the stronger is also an observable distortion of peak S, i.e. the desorption of the final 2/3 Cu.

Cyclic voltammograms of Au(111) recorded in a 0.1 M H2SO4 solution containing 0.1 mM CuSO4 + 0.01 mM TMPyP and extending to different cathodic potentials, scan rate dE/dt = 10 mV/s. TMPyP molecule (inset). As in Fig. 4, P1 and P2 mark the first two two-electron reduction steps of the adsorbed TMPyP molecules (see Fig. 8 and text)

The cyclic voltammograms shown in Fig. 10 do not exhibit clearly resolved peaks assignable to the adsorption/desorption of porphyrins. The different character of the cyclic voltammograms taken before (Fig. 4, CV1) and after (Fig. 4, CV2, and Fig. 10) adding the porphyrins into the solution arises from a superposition of the competing adsorption of sulfate anions, and porphyrin and copper cations, and the resulting current flow through the interface. STM images recorded in the 0.1 M H2SO4 + 0.1 mM CuSO4 + 0.01 mM TMPyP solution in the anodic potential range, before Cu adsorption takes place and sulfate first forms a disordered and then an ordered \(\left( {\sqrt 3 \times \sqrt 7 } \right)\) layer on the Au(111) substrate, show no additional features which could be assigned to porphyrin molecules. Also on the \({\left( {\sqrt 3 \times \sqrt 3 } \right)_1}\) co-adsorption layer of 2/3 Cu + 1/3 ML \({\text{S}}{{\text{O}}_4}^{{2 - }}\) no additional molecular features were identified in the images. These images (not shown here) indicate either the lack of TMPyP on the surface or the formation of a mobile porphyrin layer. Only at more negative potential values such as E = − 700 mV (Pt/PtO), after the formation of the first pseudomorphic Cu monolayer on Au(111) with disordered sulfate on top, the STM images reveal the formation of a disordered porphyrin layer (Fig. 11). Single quadratic porphyrin species are clearly imaged with their ligands (inset in Fig. 11b). The molecules exhibit a planar orientation with respect to the surface, however, without long range order. Only occasionally some short range order can be made out (arrows). The distribution of molecules with respect to the stable reference point marked by the white circle in panels (a)–(c) changes from image to image, which shows the diffusion of the TMPyP molecules on the disordered sulfate layer on 1 ML of Cu supported on Au(111). Note that no TMPyP molecules at all are detected on the regions of disordered SO42− adsorption on the bulk Cu(111) surface (see Fig. 9d).

In situ STM images recorded from 1 ML of Cu on Au(111) obtained after 5 min of Cu deposition at E = − 673 mV from a 0.1 M H2SO4 solution containing 0.1 mM CuSO4 and 0.01 mM TMPyP. Before taking the images the solution was diluted with 0.1 M H2SO4 + 0.01 mM TMPyP, in order to significantly decrease the deposition of Cu from solution, and the potential was lowered to E = − 699 mV. a 72 nm × 72 nm, It = 1 nA, Ut = − 43 mV; b 72 nm × 72 nm, It = 1 nA, Ut = − 200 mV; inset in b 14.5 nm × 14.5 nm, It = 1 nA, Ut = − 214 mV; c 72 nm × 72 nm, It = 1 nA, Ut = − 211 mV. At E = − 699 mV sulfate forms only a disordered layer on 1 ML Cu/Au(111) (region IV in Fig. 4, CV1). The white circle marks a stabile reference feature; the arrows indicate local patches of ordered TMPyP molecules. Potentials E determined with respect to the Pt/PtO reference electrode

An ordered TMPyP layer is only observed (Fig. 12) at a potential E = − 996 mV, where sulfate forms the stable \({\left( {\sqrt 3 \times \sqrt 7 } \right)_1}\) structure on the first completed pseudomorphic Cu monolayer on Au(111) (Fig. 5e). The large scan area (Fig. 12a) shows porphyrin domains mutually rotated by 60°/120°, and a close-up of one domain (Fig. 12b) reflects the long range order of the porphyrin layer.

In situ STM images taken from 1 ML of Cu on Au(111) in a0.1 M H2SO4 + 0.1 mM CuSO4 + 0.01 mM TMPyP solution: a 53.8 nm × 53.8 nm, It = 1 nA, Ut = − 77 mV, E = − 996 mV; b 13.1 nm × 13.1 nm, It = 1 nA, Ut = − 44 mV, E = − 993 mV (Pt/PtO). At these potentials E \({\text{S}}{{\text{O}}_4}^{{2 - }}\) forms a \({\left( {\sqrt 3 \times \sqrt 7 } \right)_1}\) ordered layer (region VI in Fig. 4, CV1); c sketch of the TMPyP layer on \({\left( {\sqrt 3 \times \sqrt 7 } \right)_1} - {\text{S}}{{\text{O}}_4}^{{2 - }}\)/1 ML Cu/ Au(111)

As shown in Fig. 6d–f in the opd region the formation of Cu multilayers with the sulfate induced Moiré structure is observed. At these potentials under the progressive copper deposition in the copper rich electrolyte the adsorbing TMPyP molecules exhibit no order and the recorded STM images (not shown) are characterized by large noise. Thus, in order to decrease the copper deposition rate the solution was diluted with 0.1 M H2SO4 + 0.01 mM TMPyP after the formation of Cu multilayers at fixed potential. Images recorded at this suppressed Cu deposition are shown in Fig. 13. A gradual increase of the TMPyP coverage is observed with deposition time (Fig. 13a–c). Although the porphyrin layer does not exhibit a long range order, a short rang ordering with increased coverage is observed, in that the TMPyP molecules form both square (sqr) and hexagonal (hex) local arrangements (see inset in Fig. 13b), as it was also observed on bulk Cu(111) in sulphuric acid solution [23].

In situ STM images of TMPyP molecules adsorbed on a Cu multilayer deposited on Au(111). The Cu deposit was obtained after 5 min deposition of copper from a 0.1 M H2SO4 + 0.1 mM CuSO4 + 0.01 mM TMPyP solution at E = − 830 mV. Then the solution was diluted with 0.1 M H2SO4 + 0.01 mM TMPyP in order to suppress the continuous deposition of Cu. a 72.2 nm × 72.2 nm, It = 1 nA, Ut = 301 mV, E = − 802 mV; b 72.2 nm × 72.2 nm, It = 1 nA, Ut = 301 mV, E = − 802 mV. The insets (sqr) and (hex) in b accentuate two observed structures, namely a square and a hexagonal arrangement of the TMPyP molecules, respectively; (sqr) 11 nm × 11 nm, It = 1 nA, Ut = 222 mV, E = − 807 mV; (hex) 10 nm × 10 nm, It = 1 nA, Ut = 238 mV, E = − 807 mV; c 72.2 nm × 72.2 nm, It = 1 nA, Ut = 301 mV, E = − 798 mV; d 72.2 nm × 72.2 nm, It = 1 nA, upper part Ut = 301 mV (TMPyP imaging), lower part Ut =6 mV (\({\text{S}}{{\text{O}}_4}^{{2 - }}\) imaging), E = − 798 mV; e 72.2 nm × 72.2 nm, It = 1 nA, Ut = 16 mV (\({\text{S}}{{\text{O}}_4}^{{2 - }}\) imaging), E = − 798 mV; f 72.2 nm × 72.2 nm, It = 1 nA, upper part Ut = 16 mV (\({\text{S}}{{\text{O}}_4}^{{2 - }}\) imaging), lower part Ut = 301 mV (TMPyP imaging), E = − 798 mV. Potentials E determined with respect to the Pt/PtO reference electrode

The STM images shown in Fig. 13a–c were recorded under “soft” tunneling conditions, i.e. with larger surface-tip distances. Under these conditions the molecular layer is not affected by the tip during the scanning process. A change to “drastic” tunneling conditions during registration of the image in Fig. 13d, where the tip approaches the surface, leads to a penetration of the tunnelling tip into the organic layer and a removal of the porphyrin species from the Cu multilayer surface as reflected in Fig. 13d, e. The exposed surface underneath exhibits the characteristic Moiré superstructure for Cu multilayer deposits. Going back to “soft” tunnelling conditions results in a tip retraction and the re-formation of the TMPyP layer (Fig. 13f), like on bulk Cu(111) as shown in Fig. 9b [60]. The newly formed porphyrin layer, however, seems to be less ordered than before the tip manipulation.

As it was demonstrated in [16] the diffusion of TMPyP molecules on Au(111) can be tuned by the electrode potential. The change of electrode potential, and thus the surface charge, controls the electrostatic attraction between the electrode and the TMPyP cations, and thereby determines whether an ordered or disordered molecular layer is formed. This control, however, is most effective only in the case of a direct adsorption of the molecules on the bare metallic electrode. The presence of any anion layer between the molecular layer and the metallic electrode acts as a “buffer”, which screens the electrode surface. Therefore, in the case of the adsorption of TMPyP on the sulfate precovered Cu/Au(111) electrode the change of the potential has less influence on the mobility of the adsorbed molecules, and thus on structural changes within porphyrin layer.

STM images recorded after porphyrin adsorption (Figs. 9, 11, 12, 13) reveal a flat orientation of the adsorbed species, as it was also observed on other surfaces under UHV conditions [13, 17, 67, 68]. This planar orientation maximizes the π bonding to the substrate. In contrast to the adsorption of porphyrins on bare metal surfaces in UHV conditions, however, the adsorption from an electrolyte solution occurs mostly on the metal electrode modified by adsorbed anions. The charged electrode surface attracts electrostatically counter ions, which leads to their specific adsorption. Hence, depending on the adsorption/desorption potential of porphyrins with respect to that of the other specifically adsorbed anions in solutions the TMPyP molecules interact directly with Au(111) or with adsorbed anions. Highly ordered porphyrin layers were observed on iodide (I) [23], chloride (Cl) [66] and sulfate (\({\text{S}}{{\text{O}}_4}^{{2 - }}\)) [60] precovered Au(111) or Cu(111) single-crystalline electrodes. Adsorbed iodide is almost uncharged and makes the electrode surface hydrophobic. Therefore, the interaction between porphyrins and preadsorbed iodide is expected to have mainly van der Waals (vdW) character [69]. Such weak interaction facilitates the diffusion of the adsorbed molecules. Sulfate anions, however, stay largely ionic on the surface, therefore the driving force for the adsorption of TMPyP cations is mainly electrostatic in nature. In this case the potential induced charge of the surface changes, and thereby the balance between all interactions, which leads to a new equilibrium and, as a consequence, a rearrangement of the porphyrin molecules compared to the bare surface. Moreover, potential induced redox reactions of the porphyrins can occur, as was demonstrated for TMPyP on iodide precovered Cu(111) [60]. In the case of Au(111) precovered with 1 ML Cu obviously strong electrostatic interactions due to the sulfate precoverage and the very negative electrode potential hinder the diffusion of the molecular porphyrin cations and the formation of a well ordered layer. In addition a high defect density arising from steps (Fig. 9a) and screw dislocations through the Cu multilayer on Au(111) (Fig. 6d) hamper the formation of long-range order.

In the case of the increased negative charge density of the electrode surface also the formation of the second porphyrin layer is even possible. Porphyrin molecules in the second layer interact less strongly with the substrate than TMPyP molecules of the first layer, but have, indeed, been observed on a chloride modified Cu(111) surface [70]. The presence of low and high contrast protrusions within one terrace observed in Fig. 13f may thus be associated with porphyrins of the second layer. However, the presence of different oxidation states of TMPyP, differently imaged by STM tip, could also be a reason for this difference in contrast.

The STM images recorded for Cu(111) (Fig. 9) prove that porphyrins are adsorbed only on the surface areas, which are covered by the Moiré structure induced by sulphate [60]. This clearly shows that the driving force for the TMPyP adsorption is electrostatic in nature. In Fig. 13 the whole surface area is covered by the sulfate induced Moiré pattern, therefore the adsorption of TMPyP is observed on all terraces.

5 Summary

Combined cyclic voltametry (CV) and in situ electrochemical scanning tunneling microscopy (EC-STM) measurements provide interesting insight into the coadsorption behavior of sulfate-anions with porphyrin (TMPyP)- and copper-cations on a Au(111) electrode. Starting at positive potentials ≥ 1000 mV (RHE) the Au(111) surface is first covered with a highly ordered \(\left( {\sqrt 3 \times \sqrt 7 } \right)R19.1^\circ - {\text{S}}{{\text{O}}_4}^{{2 - }}\) structure, which below 1000 mV (RHE) becomes disordered. At about 400 mV (RHE) first 2/3 ML copper coadsorb with SO42− anions forming a \(\left( {\sqrt 3 \times \sqrt 3 } \right)R30^\circ\) ordered layer. After adsorption of further 1/3 ML copper at about 200 mV (RHE), as suggested by CV, the first copper monolayer becomes completed which, however, must be hidden under a layer of mobile SO42− anions (and, possibly, TMPyP cations) because no ordered structure can be seen in STM images. Even though at about 100 mV (RHE) a rigid ordered SO42− adlayer does not exist the first disordered arrangement of TMPyP molecules can be imaged on the surface. Only at − 200 mV (RHE) the copper monolayer is covered again with a \(\left( {\sqrt 3 \times \sqrt 7 } \right)R19.1^\circ - {\text{S}}{{\text{O}}_4}^{{2 - }}\) structure and a dense TMPyP-layer showing first indication of ordered packing of the porphyrin molecules. It is obviously the potential dependent charge density of the surface which controls the adsorption of the respective ionic species and their coverage and order on the surface.

In the regime of opd-grown multilayers of copper showing the characteristic sulfate-induced combination of \(\left( {\sqrt 3 \times \sqrt 7 } \right)R19.1^\circ - {\text{S}}{{\text{O}}_4}^{{2 - }}\) and Moiré-superstructure the TMPyP coverage increases and the porphyrin molecules show a growing tendency to order, forming a square and hexagonal arrangement similar to what is found on bulk Cu(111). Using at this stage “drastic” and “soft” tunneling conditions enables also a tip-induced removal and re-deposition of the porphyrin molecules and, thereby, the verification of the SO42−-induced Moiré-structure underneath. The STM images prove a flat orientation of the TMPyP molecules in all their adsorption phases.

Reincreasing the electrode potential leads to a step-wise reversal of all the above described processes, i.e. Cu multilayer-, porphyrin-, 1/3 ML Cu- and 2/3 CuML Cu-desorption until the \(\left( {\sqrt 3 \times \sqrt 7 } \right)R19.1^\circ - {\text{S}}{{\text{O}}_4}^{{2 - }}\) covered and TMPyP-free Au(111) surface is restored. Interesting to note in this context is the fact, that the multi- and monolayer Cu desorption CV peaks are all much smaller than the previous Cu adsorption signals. This suggests that a part of the adsorbing Cu cations are incorporated into adsorbed TMPyP molecules and are carried away into the bulk solution as metallo-porphyrin (CuTMPyP).

References

Lei JP, Ju HX, Ikeda O (2004) Electrochim Acta 49:2453–2460

Mayer I, Nakamura M, Toma HE, Araki K (2006) Electrochim Acta 52:263–271

Kadish KM, Smith KM, Guilard R (eds) (2014) Handbook of porphyrin science: with applications to chemistry, physics, materials science, engineering, biology and medicine, vol 1–35. World Scientific, Hackensack

Jiang S, Chen X, Liu M (2004) J Colloid Interface Sci 277:396–403

Ishihara S, Labuta J, Van Rossom W, Ishikawa D, Minami K, Hill JP, Ariga K (2014) Phys Chem Chem Phys 16:9713–9746

Monti D, Nardis S, Stefanelli M, Paolesse R, Di Natale C, D’Amico A (2009) J Sens. https://doi.org/10.1155/2009/856053

Purrello R, Gurrieri S, Lanceri R (1999) Coordination Chemistry Review 190–192:683–706

Belcher WJ, Wagner KI, Dastoor PC (2007) Sol Energy Mater Sol Cells 91:447–452

Smith KM (ed) (1975) Porphyrins and metalloporphyrins. Elsevier, Amsterdam

Burrell AK, Wasielewski MR (2000) J Peptide Res 4:401–406

Barona-Castaño JC, Carmona-Vargas CC, Brocksom TJ, de Oliveira KT (2016) Molecules 21:310–337

Srour H, le Maux P, Chevance S, Simonneaux G (2013) Coord Chem Rev 257:3030–3050

Gottfried M (2015) Surf Sci Rep 70:259–379

Kunitake M, Batina N, Itaya K (1995) Langmuir 11:2337–2340

Schiavon MA, Iamamoto Y, Nascimento OR, das Dores Assis M (2001) J Mol Catal 174:213–222

He Y, Ye T, Borguet E (2002) J Am Chem Soc 124:11964–11970

Guo XL, Dong ZC, Trifonov AS, Miki K, Kimura K, Mashiko S (2005) Appl Surf Sci 241:28–32

Gottfried JM, Flechtner K, Kretschmann A, Lukasczyk T, Steinruck HP (2006) J Am Chem Soc 128:5644–5645

Flechtner K, Kretschmann A, Bradshaw LR, Walz MM, Steinruck HP, Gottfried JM (2007) J Phys Chem C 111:5821–5824

Buchner F, Warnick KG, Wölfle Th, Görling A, Steinrück HP, Hieringer W, Marbach H (2009) J Phys Chem C 113:16450–16457

Phan TH, Wandelt K (2013) Surf Sci 607:82–91

Phan TH, Wandelt K (2014) Beilstein J Org Chem 10:2243–2254

Hai NTM, Gasparovic B, Wandelt K, Broekmann P (2007) Surf Sci 601:2597–2602

Graham DC, Soderberg BA (1954) J Chem Phys 22:449–459

Schmicker W, Santos E (2010) Interfacial electrochemistry, 2nd edn. Springer, Berlin

Grosberg AY, Nguyen TT, Shklovskii BI (2002) Rev Mod Phys 74:329–345

Batina N, Kunitake M, Itaya KJ (1996) Electroanal Chem 405:245–250

Sashikata K, Sugata T, Sugimasa M, Itaya K (1998) Langmuir 14:2896–2902

Whitesides GM, Mathias JP, Seto CT (1991) Science 254:1312–1319

Andricacos PC, Uzoh C, Ducovic JO, Horkans J, Deligianni H (1998) IBM J Res Dev 42:567–574

Huynh TMT, Hai NTM, Broekmann P (2013) J Electrochem Soc 160:D3063–D3069

Wilms M (1999) PhD dissertation, University of Bonn, Bonn

Wilms M, Kruft M, Bermes G, Wandelt K (1999) Rev Sci Inst 70:3641–3649

Schultze JW, Dickertmann D (1976) Surf Sci 54:489–505

Madry B, Wandelt K, Nowicki (2016) Electrochim Acta 217:249–261

Nowicki M, Wandelt K (2017) Handbook of solid state chemistry, vol 3 characterization. Wiley, Weinheim, pp 183–243

Harten U, Lahee AM, Toennies J, Wöll C (1985) Phys Rev Lett 54:2619–2622

Barth JV, Brune H, Ertl G, Behm RJ (1990) Phys Rev B 42:9307–9318

Kolb DM, Schneider J (1986) Electrochim Acta 31:929–936

Dretschkow T, Wandlowski T (2003) Topics in applied physics. In: Wandelt K, Thurgate S (eds) Solid-liquid interfaces, macroscopic phenomena and microscopic understanding, vol 85. Springer, Berlin, pp 259–321

Cuesta A, Kleinert M, Kolb DM (2000) Phys Chem Chem Phys 2:5684–5690

Broekmann P, Wilms M, Arenz M, Spänig A, Wandelt K (2003) Topics in applied physics. In: Wandelt K, Thurgate S (eds) Solid-liquid interfaces; macroscopic phenomena—microscopic understanding. Springer, Heidelberg, p 141

Lennartz M, Broekmann P, Arenz M, Stuhlmann C, Wandelt K (1999) Surf Sci 442:215–222

Ataka KI, Osawa M (1998) Langmuir 14:951–959

Wilms M, Broekmann P, Stuhlmann C, Wandelt K (1998) Surf Sci 416:121–140

Gentz K, Wandelt K (2012) Chimia 66:44–51

Broekmann P, Wilms M, Spänig A, Wandelt K (2001) Prog Surf Sci 67:59–77

Broekmann P, Wilms P, Kruft M, Stuhlmann C, Wandelt K (1999) J Electroanal Chem 467:307–324

Frumkin A (1933) Zeit Phys Chem A164:121–133

Buderski E, Staikov G, Lorenz WJ (1996) Electrochemical phase formastion and growth—an introduction to the initial stages of metal deposition. Wiley, Weinheim

Möller F, Magnussen OM, Behm RJ (1995) Electrochim Acta 40:1259–1265

Nagy G, Wandlowski Th (2003) Langmuir 19:10271–10280

Nakamura M, Endo O, Ohta T, Ito M, Yoda Y (2002) Surf Sci 514:227–233

Shi Z, Wu S, Lipkowski J (1995) Electrochim Acta 40:9–15

Madry B, Wandelt K, Nowicki M (2015) Surf Sci 637–638:77–84

Madry B, Wandelt K, Nowicki M (2016) Appl Surf Sci 388:678–683

Edens GJ, Gao XP, Weaver MJ (1994) J Electroanal Chem 375:357–366

Funtikov AM, Stimming U, Vogel R (1997) J Electroanal Chem 428:147–153

Wandlowski T, Ataka K, Pronkin S, Diesing D (2004) Electrochim Acta 49:1233–1247

Hai NTM, Wandelt K, Broekmann P (2008) J Phys Chem C 112:10176–10186

Fleischer EB (1962) Inorg Chem 1:493–495

Neri BP, Wilson GS (1972) Anal Chem 44:1002–1009

Hambrigh P, Fleischer E (1970) Inorg Chem 9:1757–1761

Richoux MC, Neta P, Harriman A, Baral S, Hambright P (1986) J Phys Chem 90:2462–2468

Baral S, Neta P, Hambright P (1984) Radiat Phys Chem 24:245–255

Hai NTM, Furukawa S, Vosch T, DeFeyter S, Broekmann P, Wandelt K (2009) Phys Chem Chem Phys 11:5422–5430

Scudiero L, Barlow DE, Mazur U, Hipps KW (2001) J Am Chem Soc 123:4073–4080

Hipps KW, Scudiero L, Barlow DE, Cooke MP Jr (2002) J Am Chem Soc 124:2126–2127

Röefzaad M, Wandelt K (2013) In: Wieckowski A, Korzeniewski C, Braunschweig B (eds) Vibrational spectroscopy of electrically charged interfaces. Wiley, New York, pp 317–326

Hai NTM (2017) PhD-thesis. Univeristy of Bonn, Bonn

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the University of Wrocław for the financial support (1010/S/IFD and 0420/2534/17). We acknowledge the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation for the EC-STM apparatus donation, DAAD for founding the scientific exchange between University of Bonn and University of Wroclaw, and Nanotec Electronica for the WSxM software.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Madry, B., Morawski, I., Kosmala, T. et al. Porphyrin Layers at Cu/Au(111)–Electrolyte Interfaces: In Situ EC-STM Study. Top Catal 61, 1335–1349 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11244-018-0985-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11244-018-0985-3