Abstract

Hydraulic flow, electrical flow and the passage of elastic waves through porous media are all linked by electrokinetic processes. In its simplest form, the passage of elastic waves through the porous medium causes fluid to flow through that medium and that flow gives rise to an electrical streaming potential and electrical counter-current. These processes are frequency-dependent and governed by coupling coefficients which are themselves frequency-dependent. The link between fluid pressure and fluid flow is described by dynamic permeability, which is characterised by the hydraulic coupling coefficient (Chp). The link between fluid pressure and electrical streaming potential is characterised by the streaming potential coefficient (Csp). While the steady-state values of such coefficients are well studied and understood, their frequency dependence is not. Previous work has been confined to unconsolidated and disaggregated materials such as sands, gravels and soils. In this work, we present an apparatus for measuring the hydraulic and streaming potential coefficients of high porosity, high permeability consolidated porous media as a function of frequency. The apparatus operates in the range 1 Hz to 2 kHz with a sample of 10 mm diameter and 5–30 mm in length. The full design and validation of the apparatus are described together with the experimental protocol it uses. Initial data are presented for three samples of Boise sandstone, which present as dispersive media with the critical transition frequency of 918.3 ± 99.4 Hz. The in-phase and in-quadrature components of the measured hydraulic and streaming potential coefficients have been compared to the Debye-type dispersion model as well as theoretical models based on bundles of capillary tubes and porous media. Initial results indicate that the dynamic permeability data present an extremely good fit to the capillary bundle and Debye-type dispersion models, while the streaming potential coefficient presents an extremely good fit to all of the models up to the critical transition frequency, but diverges at higher frequencies. The streaming potential coefficient data are best fitted by the Pride model and its Walker and Glover simplification. Characteristic pore size values calculated from the measured critical transition frequency fell within 1.73% of independent measures of this parameter, while the values calculated directly from the Packard model showed an underestimation by about 12%.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Hydraulic flow, electrical flow and the passage of elastic waves through porous media are all linked by electrokinetic processes (Jouniaux and Zyserman 2016; Glover 2015; Jouniaux and Ishido 2012; Jouniaux and Bordes 2012). Such processes have the potential for allowing crustal rocks to be probed in more detail. For example, the electro-seismic method perturbs the subsurface with elastic waves and measures the resulting electrical potential (Glover and Jackson 2010). The conversion from elastic wave energy to electrical energy is called the streaming potential coefficient (Csp) (Glover 2015). This value depends on frequency as well as other factors such as porosity and permeability (Peng et al. 2018a, b, 2019). For steady-state coupling (Cspo), there is a growing body of experimental measurements on rocks (e.g., Walker and Glover 2018; Walker et al. 2014; Vinogradov et al. 2010; Alkafeef and Alajmi 2007; Jouniaux and Pozzi 1995a, b, 1997) and glass-bead packs (Glover and Déry 2010), together with an increasingly well-understood supporting theoretical framework (Glover 2018; Glover et al. 2012a; Glover and Déry 2010, Revil and Glover 1997, 1998; Revil et al. 1999). However, the situation is very different for frequency-dependent coupling. Here there is little experimental data on the streaming potential coefficient as a function of frequency Csp for sands and glass-bead packs (Tardif et al. 2011; Glover et al. 2012b, c; Reppert and Morgan 2001; Reppert et al. 2001) and only one measurement made on rocks (Reppert 2000).

As described in detail in Glover et al. (2012b), there are two main methods for measuring either frequency-dependent permeability or streaming potential coefficient. These are (i) transient measurements using a percussive source and (ii) harmonic measurements at a single frequency using a driver such as a loudspeaker. The percussive approach has been used to provide electrokinetic signals that might be similar to those encountered during electro-seismic conversion of a seismic wavelet (Bordes et al. 2006; 2008). However, because the input signal is a mix of frequencies, this method cannot be used to provide the dynamic permeability or the streaming potential coefficient at a given frequency, unless the applied and received pressure and voltage signals are separated into their Fourier components as suggested by Reppert and Morgan (2001). Attempts have been made to implement this approach but with no success (Glover et al. 2012b). Consequently, the harmonic approach has provided all frequency-dependent data published to date (Tardif et al. 2011; Glover et al. 2012b, c; Sears and Groves 1978; Cooke 1955; Packard 1953).

The lack of data is not confined to frequency-dependent coupling coefficients but is also apparent in experimental measurements of frequency-dependent (so-called dynamic) permeability. Here, once again, there are no apparent data for rocks, though some data exist for capillary bundles, fused glass beads and crushed glass (Charlaix et al. 1988) which have been made using a harmonic driver techniques (Dimon et al. 1988; Kranz et al. 1990; Song and Renner 2007). Most publications focus on the development of theoretical models (Sheng and Zhou 1988; Johnson et al. 1987) and heuristic models (Steeb 2017; Renner and Steeb 2015; Dinariev and Mikhailov, 2011; Knackstedt et al. 1993), as well as the application of dynamic permeability in seismic exploration and borehole analysis (e.g., Liu et al. 2016). In all cases, the transition from viscous to inertial flow is clear and well understood. This transition is also an important constraint on frequency-dependent streaming potential because the streaming potential depends upon fluid flow.

In previous papers (Tardif et al. 2011; Glover et al. 2012b, c), we described the design, testing and implementation of an apparatus for measuring the frequency-dependent permeability and streaming potential coefficient for loose aggregates such as sands and soils. In this paper, we present the design, construction and validation of a new experimental apparatus for measuring the frequency-dependent streaming potential coefficient of cylindrical core samples of high permeability. The apparatus has been tested on a sample of Berea sandstone. Presentation of the frequency-dependent permeability and streaming potential coefficient of a fuller suite of Berea and Boise samples will be given in a future paper. Both the in-phase and in-quadrature components of the streaming potential coefficient have been measured with an uncertainty of better than ± 4%. The experimental measurements show the critical frequency at which the out of phase component is maximal, and the frequency of this component is shown to agree very well with both the permeability and the grain size of the sample. The experimental measurements have been modelled using several different methods.

2 Theoretical Background

The basic theoretical background can be found in many of the papers cited in the introduction, including those of Packard (1953), Pride (1994), Reppert et al. (2001) and Glover et al. (2012c). Initial theoretical model development was carried out for capillary bundles (Packard 1953) and then extended to porous media (Pride 1994) before being simplified (Glover et al. 2012c). However, there is little difference between the models when implemented for the range of common geophysical parameters.

Packard’s analysis of Navier–Stokes equation with a harmonic forcing term can be written as

where ρ is the fluid density (in kg/m3), \( \overline{\upsilon } \) is the flow velocity (in m/s), ω is the frequency (in rads/s), r is the radial distance measured from the centre of the capillary (in m), t is time (in s), P is the fluid pressure, and η is the fluid viscosity (in Pa s).

The hydraulic coupling coefficient (Chp) is expressed in velocity of flow per pressure difference, which is related to the dynamic permeability, and is given by

and where l and a are the length and the radius of the capillaries (in m), and J1 and J0 are Bessel functions of the first and zeroth kind, respectively.

The streaming potential coefficient can also be obtained from Eq. (1) as

and where ε is the fluid permittivity (in F/m), ζ is the zeta potential (in V), and σ is the electrical conductivity of the fluid (in S/m), the latter of which can be measured with techniques described in Glover (2015). Equation (3) was written in simpler form by Reppert et al. (2001) but with an error in the equation which was corrected by Tardif et al. (2011). In practice the Packard and Reppert et al. equations provide almost identical values.

While the previous equations were derived for bundles of capillary tubes, Pride (1994) provided an equation for streaming potential coupling coefficient for porous media that is based on the theory of the electric double layer

where ωt is the critical (transition) frequency (in rads/s), δ is the Debye length (in m) (see Glover 2015), Λ is the characteristic pore size (in m), kDC is the steady-state permeability (in m2), and τe is the electrical tortuosity [τe = ϕ1−m, where m is the cementation exponent (see Glover 2015)]. Walker and Glover (2010) provided a simplification of Eq. (4) for the case where Λ ≫ δ, i.e., when the pore fluid is medium to high salinity. Since the experiments carried out in this work were for pore fluids of a salinity Cf = 0.1 mol/dm3, the Pride model and its simplification provide almost identical values.

It should be noted in each of Eqs. (2–4), the term outside the square brackets is the steady-state contribution to permeability or streaming potential, respectively.

Equations (2–4) above imply that it would be possible to measure the effective pore size of porous media, as well as a number of other petrophysical parameters, by making either frequency-dependent hydraulic and/or streaming potential coupling coefficient measurements, where the steady-state versions of each measurement would not provide sufficient information. If that were to be the case, then the use of frequency-dependent hydraulic measurements would be easier to implement, providing that Eq. (2), which relies on the assumption that the porous medium can be represented by capillary bundle, was found to represent real porous media well. However, both the frequency-dependent hydraulic and streaming potential measurements are not easy to make, and simpler alternatives would probably be preferred. In any case, this paper cannot provide sufficient data to test Eqs. (2–4) fully and to examine the interplay between the frequency-dependent streaming potential coupling coefficient and the frequency-dependent hydraulic coefficient, which is a task for future papers. This paper provides the design of an apparatus together with a validated experimental methodology for making the measurements that will be required to fully test those equations.

Figure 1 shows the general behaviour of frequency-dependent (dynamic) permeability and streaming potential coefficient schematically as a function of frequency as given by the solutions of Eqs. (2) and (3) for both in-phase and in-quadrature components. In this example, we have imposed a critical frequency of 400 Hz which leads to a peak in the in-quadrature curves at this frequency. In rocks, the critical frequency depends upon fluid and rock properties as described in the next section.

It is important to consider the physical meaning of the in-phase (real) and in-quadrature (imaginary) contributions to the permeability and the streaming potential coupling coefficient in order to understand exactly what is to be measured. The streaming potential coefficient is defined as the ratio of the streaming potential to the pressure drop across the sample, as described in the review by Glover (2015). However, it is the fluid velocity that separates mobile diffuse layer charge and immobile diffuse layer charge, which generates the streaming potential. This implies that the frequency dependence of the streaming potential coupling coefficient depends on that of the dynamic fluid permeability. The dynamic fluid permeability at low frequencies is controlled by viscous flow that is represented by the real (or in-phase) part of the dynamic permeability. However, when a critical frequency is reached, the inertial acceleration of the fluid begins to control the flow (e.g., Charlaix et al. 1988; Reppert et al. 2001). The inertial acceleration is represented by the in-quadrature part of the dynamic permeability. Hence, we might expect the real and imaginary parts of the streaming potential coupling coefficient to be influenced by the same transition from viscous dominated to inertial-dominated fluid flow, as shown in Fig. 1 by the similarity in the critical frequency at which the red and blue in-quadrature curves peak. In this scenario, the transition frequency is the same as the critical frequency at which viscous-dominated fluid flow becomes inertia-dominated.

In general, the dynamic permeability and streaming potential coefficient become progressively out of phase with the driving pressure as frequency increases towards the critical frequency. This is shown by the increase in the quadrature component. The effect becomes greatest at the critical frequency where a peak in the quadrature component occurs, before returning to zero once more as frequency increases after the critical frequency. However, the in-phase component also changes with frequency due to the requirement to conserve energy. The in-phase component is constant at low frequencies and equal to the steady-state permeability and streaming potential coefficient, respectively. As frequency increases, the in-phase component reduces through the critical frequency to a new level at frequencies higher than the critical frequency. In the case of dynamic permeability and streaming potential coefficient, the high-frequency value is expected to be very small.

Since the streaming potential coefficient describes a pressure-voltage coupling that depends upon the flow of fluid, we would expect that (i) the critical frequency of the streaming potential behaviour would be the same as the transition frequency of the dynamic permeability, and (ii) the functional behaviour of both the in-phase and in-quadrature for streaming potential and dynamic permeability would be similar. Indeed, measurements so far seem to indicate that the critical and transition frequencies coincide, and this is supported by the theoretical models (Packard 1953; Pride 1994; Reppert et al. 2001; Glover et al. 2012c). However, it has been noted in measurements on glass beads and Ottawa sand by Glover et al. (2012c) that the frequency dependence of fluid flow and of the streaming potential coupling coefficient does not coincide. The normalised dynamic permeability of a bundle of capillary tubes follows a Debye model (please see Tardif et al. (2011) for a description of the Debye model) approximately for all frequencies, while the normalised streaming potential coupling coefficient is consistent with the same Debye model only up to the transition frequency, then deviates from it significantly.

This paper contains no new theoretical development, but describes the modification and extension of the design of an existing apparatus for testing the frequency-dependent streaming potential of loose aggregates to provide a completely new apparatus that is capable of measuring the frequency-dependent streaming potential and permeability of rock core plugs. The paper also includes the testing and validation of the new apparatus, providing the first published frequency-dependent streaming potential data on whole rock samples.

The apparatus we describe can simultaneously measure the harmonic frequency dependence of permeability and the harmonic frequency dependence of streaming potential. It has been suggested that the harmonic frequency dependence of streaming potential could be calculated if one knew the frequency dependence of permeability and the steady-state streaming potential coupling coefficient. However, the divergences in the frequency dependence are of the permeability and streaming potential at post-critical frequencies illustrated in Fig. 1 show that that is not possible, because the two measurements have distinctly different frequency dependencies, presumably arising from more than one relaxation source. In this paper, we have chosen not to explore the comparison between these datasets with the small number of data that we present as a validation for our methodologies and plan to publish a further paper with much more data and exploring the relationship between the two measurements.

3 Apparatus Specification

This paper describes the design of an apparatus for measuring the streaming potential of cylindrical cores of porous rocks as a function of frequency. The previously developed apparatus for loose aggregates was used as a starting point (Glover et al. 2012b), and many of the general considerations in that paper are also relevant for measurements on core plugs. Table 1 shows the specifications which we defined for the apparatus described in this work, and which represent the result of a number of compromises. In this table, the values in the minimum and maximum columns refer to design minima and maxima that are possible with the apparatus for individual parameters but not necessarily achieved during operation. Consequently it would not be correct to infer that all of the minima or maxima occur during operation. For example, a piston displacement of 22 mm does not occur when operating at 2000 Hz—indeed, at 2000 Hz the piston displacement is very small and approaches 0.1 mm.

A minimum frequency of 2 Hz has been specified, which is the lower limit of the electromagnetic shaker that was available to us (VTS-100). The maximum limit of this shaker is 6.5 kHz. However, in practice the maximum frequency was 2 kHz, resulting from the fact that the shaker provides a decreasing piston displacement as frequency is increased. The limit of 2 kHz was chosen as it represents the highest frequency at which streaming potential measurements may be made reliably and with an uncertainty of less than ± 10%.

The design calculations in Glover et al. (2012b) are as valid for indurated porous media as they are for loose aggregates. This analysis shows that if we use a combination of DPX101-250 and DPX101-5 K dynamic pressure transducers, for which the maximum fluid pressure is 250 psi (1.724 MPa) and 5000 psi (34.47 MPa), respectively, it is possible to make measurements on core samples in the frequency range 2 Hz to 2000 Hz for samples that are up to 10 mm long with a piston displacement of 0.1 mm, a porosity of 0.3, and pore radii larger than 1 μm. A rule of thumb calculation shows such a sample has a permeability greater than 1.875 × 10−14 m2 (18.94 mD). Consequently, the apparatus has been designed to accommodate samples ranging length between 5 mm and 40 mm, and requiring piston displacements in the range 0.1 mm to 22 mm. The provision for longer samples allows samples with large porosity and pore size to be measured effectively and accurately by increasing the harmonic pressure difference which can be generated across them. Displacement measurements can only be made to an accuracy of ± 0.05 mm by LVDT (see Table 1), but this measurement is not used in the calculation of streaming potential coefficient or dynamic permeability. The specified sample diameter is 25.4 mm and corresponds to the availability of suitable core sleeving material as well as being approximately the same as the area of the piston. Samples with porosities less than 0.3 may be measured over the entire frequency range providing their pore radii are large enough to allow the developed pressure to be measured by the pressure transducers, and otherwise over a restricted frequency range. Counter-intuitively, lower porosity samples provide lower values of critical frequency. Hence, samples with low porosity and permeabilities provide critical frequencies below 1 kHz and can be measured providing they do not generate pressures greater than those which may be accommodated by the pressure transducers (5000 psi).

As previously, we should also consider the relationship between critical frequency and the characteristic pore radius. This is given by the relationship (Glover et al. 2012b)

Figure 2 shows the value of critical frequency (fcrit, in Hz) and its associated steady-state permeability (in mD) for rock samples characterised by a given pore radius r (in m), porosity ϕ and cementation exponent m. The critical frequency increases by two orders of magnitude for every order of magnitude decrease in pore radius. Consequently, only porous media with large pore sizes can be measured by the apparatus, given its maximum operational frequency of 2 kHz.

a Critical frequency (fcrit, in Hz) as a function of modal pore radius (reff) for various values of fluid viscosity (and fluid density = 997 kg/m3). Here, the modal pore radius is that calculated from the modal pore throat radius (rPT) according to reff = 1.6585 × rPT, which was derived by Glover and Déry (2010). Aqueous fluid viscosities of 0.8891, 0.5474 and 0.1824 mPa s, correspond to temperatures of 25 °C, 50 °C and 150 °C, respectively. Steady-state permeability as a function of b modal pore radius for various values of porosity, c porosity for various values of cementation exponent, and d cementation exponent for various values of pore radius. The approximate operational range of the new apparatus is shown in each case

The permeability depends on porosity, cementation exponent and pore size. Parts (b) to (d) of the figure explore these inter-related parameters. The effects of increasing pore size, and porosity, and decreasing cementation exponent leading to increases in the steady-state permeability are demonstrated clearly in the figure. In each case, the approximate operational range of the new apparatus is shown based on a maximum operational frequency of 2 kHz and our requirement that the accurate fitting of a critical frequency to the in-phase (IP) and in-quadrature (IQ) data requires at least half of the dispersion to be measureable, i.e., fcrit≤ fmax = 2 kHz.

If the critical frequency is to fall below our high-frequency limit of 2 kHz, for typical values of water density and viscosity at room temperature conditions, and a rock with a porosity of 0.1 and a typical cementation exponent of m = 2, the radius of conductive pores needs to be greater than 33.8 µm, and such a rock would have an associated steady-state permeability of approximately 1.4 D, while a carbonate rock with a porosity of 0.15 and a cementation exponent of 3 would have an associated steady-state permeability of approximately 482 mD.

4 Apparatus Design

4.1 Generalities

There are three main aspects of the apparatus design: (a) the core holder, (b) the transducers, and (c) the harmonic drive mechanism. These are described in more detail below, in each case setting out (i) what is required from each component, (ii) the conditions it operates under, and (iii) a description of the commercially obtained or modified item.

The simplest way to provide a suitable holder for a core sample is by using a modified Haskel-type cell. The transducer design includes two pressure sensors with fast response times, two non-polarising electrodes and two LVDTs for measuring the piston position. The apparatus shares the same drive mechanism as used in a previous apparatus to measure sands and glass beads (Glover et al. 2012b; Tardif et al. 2011) but within a new sample holder and transducer arrangement.

4.2 Sample Cell

The sample cell is required to hold the core sample while allowing fluids to pass through it axially, while at room temperatures and raised confining pressure and fluid pressure conditions. It is made of insulating material in order that the streaming potential generated from electrokinetic processes can be measured without its associated streaming potential counter-current being drained to earth and to minimise thermos-electric and magneto-electric potentials. Consequently, the cell was used in a temperature stable environment (controlled to within ± 0.2 °C) and in the absence of strong magnetic fields. It is equally important that no part of the cell, driver, fluid, or fluid tanks acts as an antenna in order to reduce electrical noise, requiring strong common grounding that allows no ground loops. Since the apparatus is to be used with a range of fluid salinities (10−6–2 mol/dm3) and pH (4–11), it is also important that the wetted parts of the apparatus are sufficiently resistant to corrosion.

Figure 3 shows labelled schematic diagrams of (a) the existing apparatus, and (b) the new apparatus, while Part (c) of the figure shows the new sample cell at an expanded scale. Figure 4 shows photographs comparing the new apparatus with the existing apparatus (Tardif et al. 2011), showing the Faraday cage and various electrical connections and preamplifiers in each case.

The apparatus for measuring the frequency-dependent streaming potential coefficient of cylindrical samples of porous materials. a Diagram of the previous apparatus (Tardif et al. 2011). b Labelled x–y section of the new apparatus. c Larger scale x–y section of the sample cell of the new apparatus. Please note that for clarity none of these figures show the aluminium panelling and doors, which act as a Faraday cage

a The previous apparatus (Tardif et al. 2011) which was designed for sands, glass beads and loose aggregates. b The new apparatus for porous core plugs (left), the cooling tube to the shaker and grey instrument boxes (centre) and the control electronics (right). Faraday cage doors are open in both instruments

The sample is housed in a modified Haskel cell with input and output flow channels. The pressure sensor ports and electrical lead-through for conveying the electrode potentials are housed in the polyethylene endpieces between which the sample cell sits. In addition, one end of the cell was provided with a large aperture for the driving piston. A supporting lip and spring were used at the outlet and the inlet end, respectively, to prevent any lateral movement of the core sample. There are three transducer connections in the endpieces at each end of the sample holder: (i) one threaded connection to house a high-frequency pressure transducer, (ii) one crimp connector allowing the insertion of an Ag/AgCl non-polarising electrode, and (iii) one lead-through allowing the passage of wires carrying electrical potential signals from Pt-blacked platinum gauze electrodes (see Glover et al. 1994) that straddle the flow path in the cell at each end face of the sample. The sample cell is held rigidly between the endpieces, and to the heavy steel frame and baseplate by a hydraulic ram.

Fluids were passed from an input fluid reservoir into the apparatus via a two-way valve. The input fluids were aqueous solutions which had been vacuum degassed and fully equilibrated with the sample by previously pumping them through the sample until the electrical conductivity and pH of the stock solution attained a stable value (as described in Walker et al. 2014). The electrical conductivity and pH of the input fluids were monitored in real time during experiments, while aliquots of the output fluid were also tested. The output fluid was passed to an output reservoir. During experiments, the output fluid reservoir was placed on a mass balance in order that the mean flow rate could be measured and logged gravimetrically. Between experiments, the output fluid was pumped back into the input reservoir. The apparatus was also run using steady-state flow provided by a Pharmacia P-500 pump. This allows the steady-state permeability and streaming potential coefficient to be measured.

The temperature of the fluids was measured by inserting a metal-encased PT100 RTD probe into the input fluid reservoir. The grounding of this probe, which connected to its metal case also acted as the primary ground for the entire apparatus.

4.3 Transducers and Preamplification

The measurement of frequency-dependent streaming potential requires the instantaneous measurement of the imposed pressure difference between the fluid at the two faces of the sample as well as the instantaneous electrical potential difference between the fluid at the two faces of the sample which results. The measurement of dynamic permeability also requires the measurement of piston position such that the instantaneous flow rate can also be measured. Consequently, the apparatus needs to be equipped with a non-polarising electrode at each end of the sample, a fast-reaction pressure transducer at each end of the sample, and an LVDT between the piston and the sample cell.

In our case we provided:

- 1.

One dynamic pressure sensor port accessing the fluid pressure at each end of the sample. These were fitted with either (i) DPX101-250 (250 psi max.), (ii) DPX101-5 K (5000 psi max.), or (iii) 102B (5000 psi max.) pressure transducers (Omega Engineering and PCB Piezotronics corp., respectively). These transducers have a reaction time of 1 μs, which in theory would allow frequencies up to 125 kHz to be characterised accurately, and in our case allows there to be at least 250 measured data points per cycle for a maximum driving frequency of 2 kHz. The two pressure signals are passed to two matched preamplifiers and hence to a National Instruments USB-6229 data acquisition system that is controlled by LabView. The preamplifiers, which were designed and constructed in our laboratory, are based on a quad low-noise TL074IN J-FET input operational amplifier chip from Texas Instruments. All relevant specifications are given in Table 1.

- 2.

One Ag/AgCl electrode port accessing the fluid electrical potential at each end of the sample. When used, these were fitted with ET072-1 miniature non-refillable PEEK-bodied electrodes from EDAQ or a similar electrode from Cypress Systems. In each case, the electrodes were 65 mm long and 2 mm in diameter and secured in place using a 0.125″ polymer Swagelok fitting and PTFE tape.

- 3.

One electrical lead-through at each end of the sample, each allowing a wire carrying the potential of a Pt-blacked platinum gauze electrode to exit the cell. The lead-through was made by passing the wire into a short section of 0.125″ polymer tube and glued in place. That section of tube was then passed through a 0.125″ polymer Swagelok compressional fitting in the sample cell. The potential measurements are amplified using a bespoke differential preamplifier based on Texas Instruments TL074IN J-FET input operational amplifier chips with an input impedance greater than 1012 Ω and slew rate of 13 V/μs. The high input impedance is required because the resistance of rocks ranges from very low values for high porosity, highly connected rocks that are saturated with saline pore fluids to extremely high values for low porosity rocks that are saturated with low salinity fluids. Consequently, the measurement circuitry needs to have an input impedance of at least 109 Ω. The 13 V/μs slew rate is sufficient for the preamplifiers to follow a signal up to 4.83 MHz, which is much better than required. The output of the preamplifier is logged by a National Instruments USB-6229 data acquisition system and controlled by LabView.

- 4.

One 0.125″ polymer Swagelok compressional fitting to take a PT100 RTD temperature probe.

- 5.

Two LVDTs (LD610-15 and LD620-15/25 from Omega Engineering) were used to measure the distance between the sample cell and the piston, and between the piston and the shaker.

The arrangement of all the control, flow, transducer and logging instrumentation is shown in Fig. 5.

General arrangement of all the control, flow, transducer and logging instrumentation. The fluid flow loop is shown in blue. The confining pressure and axial pressure systems are not shown for simplicity but consist of a simple regulated N2 gas pressure with valving for the former and a hydraulic pump actioned system for the latter

4.4 Harmonic Drive

The harmonic drive was provided by a VTS-100 electromagnetic shaker (Vibration Test Systems Inc.) mounted on a trunnion and having a separate cooling system. The shaker specifications are shown in Table 2. The shaker provides a powerful, high-quality harmonic drive, which surpasses the power available from loudspeakers. The shaker was driven by a sine wave provided by a GW Instek (SFG-2110) function generator which was amplified using an audiophile quality Crown XTi 2002 800 W @ 4Ω dual channel amplifier. The quality of the drive signal was monitored using Tektronix TDS2014B 200 MHz digital storage oscilloscope, with a 2 × 109 samples per second sampling rate. All signal cabling was 50 Ω shielded coaxial cable to reduce noise and ensure purity of the signal. The sole aspect of difference in the drive system compared with the previous apparatus is a redesign of the piston. The new piston design includes a self-centring joint which enables the piston to move freely and normally in the cell’s entrance aperture when the shaker is not aligned perfectly with the cell and consequently reduces uneven wear of the piston seals. The shaker and its trunnion are connected to a heavy steel baseplate with 4 shimmed 10-mm-diameter steel bolts to ensure that the connection is extremely solid at all experimental frequencies.

5 Experimental Methodology

5.1 Experimental Modes

Experiments were run in three different modes:

- (i)

the DC mode, where a Pharmacia P-500 pump is used to flow fluid through the sample at a steady rate to measure the steady-state streaming potential coefficient and steady-state permeability,

- (ii)

the Push–Pull AC mode, where the fluid is isolated within the apparatus and the harmonic drive is used to alternately push and pull the pore fluid through the rock with no net movement of fluid, and

- (iii)

the Pumped AC mode, in which fluid is constantly supplied to the inlet of the apparatus via a one-way valve, allowing the harmonic drive to push fluid through the rock on the outward stroke and then draw new fluid into the apparatus with the return stroke.

We found that the Push–Pull AC mode gave the better quality data but could not be used for lower permeability samples and in any case could not be continued for more than 20 s before cavitation of the fluids became a problem. In the Pumped AC mode, fluids flow from the input reservoir through a one-way valve directly into the apparatus during the operation of the harmonic drive. The harmonic drive consequently behaves as a pump. The consequence of this arrangement is that the push cycle of the measurement moves fluid through the sample, and the pull cycle draws new fluid from the input reservoir into the upstream part of the apparatus. One would expect, therefore, a half-wave rectified pressure signal and a corresponding streaming potential signal, which is approximately what is measured. In each mode, a harmonic streaming potential is generated in each direction that is in antiphase with the imposed pressure and resulting fluid flow.

5.2 Experimental Methodology

The following processes were carried out to make the physical measurements. A sample of core of 10 mm diameter and less than 20 mm long was taken, measured for mean length and diameter, cleaned, dried and subjected to conventional helium porosimetry and Klinkenberg-corrected gas permeametry. It was then resaturated with the chosen aqueous electrolyte which we will call the process fluid (in our case a vacuum degassed 0.1 mol/dm3 NaCl solution). The solution itself was subjected to electrical conductivity, pH, density and viscosity determinations at the laboratory temperature.

The sample was then inserted into the cell holder complete with unconnected transducers and filled with the process fluid. The cell was filled with process fluid by holding the cell vertically and pumping fluid into the cell through its outlet until the aperture for the piston was brim-full of process fluid. At that point, the pumping was stopped and the piston was carefully inserted, allowing excess fluid to leak-off or flow back through the newly disconnected outlet. The cell holder was then clamped in place, and the piston and LVDTs were connected. Degassed process fluid was then flowed into the cell through its inlet and out again through its outlet in such a way that the fluid is recycled many times. During this procedure, the DC electrical conductivity and pH of the process fluid were monitored. Recycling was stopped only when the fluid was in equilibrium with the sample as indicated by a stable fluid conductivity and pH. It was noted that this time was much shorter than encountered in the previous DC streaming potential measurements (Walker et al. 2014; Walker and Glover 2018) and this was attributed to the much smaller sized sample used in this case. During equilibration, the cell was checked for gas bubbles by partially unscrewing all lead-throughs and ports until they leaked, and by carrying out flow with a back-pressure regulator on the downstream side set to 200 psi. The raised pressures force gas bubbles in the sample and elsewhere in the cell and flow lines to dissolve in the water, returning to gas once more when the pressure drops at the back-pressure regulator. Monitoring of the transparent flow lines for gas bubbled downstream of the BPR allows a judgement to be made whether all accessible gas has been removed from the experimental system.

The sample was then ready for measurement. First steady-state measurements of permeability and streaming potential coefficient were made by pumping the process fluid through the sample at 5 or 6 flow rates, recording the fluid flow rate and pressure differences across the sample for each. Although we used a calibrated pump rate, the flow rate data we used in the measurements were obtained gravimetrically by placing a beaker on a mass balance that was connected to LabView. Time was measured by the logging computer for greatest accuracy. Steady-state permeability and streaming potential coefficient were calculated in the conventional manner.

The sample was then either subjected to a set of Push–Pull or a Pumped AC measurements at a number of different frequencies starting at 2 Hz and increasing the frequency to as close to 2 kHz as possible. For each frequency, the shaker was run for approximately 20 s while data were collected. At 2 Hz only 40 cycles can be collected in 20 s, but the data are of high quality and the averaged values provide high-quality final values. At 2 kHz, 40,000 cycles can be collected and the average of these compensates somewhat for their generally lower quality. The raw data comprise the fluid pressure and the electrical potential at the sample inlet face, and the same parameters at the sample outlet face, as well as the piston position, all as a function of time. After the experiment, the apparatus was completely disassembled.

5.3 Dynamic Permeability

Dynamic permeability at each frequency was calculated using the following procedure. The instantaneous flow rate Q (in cm3/s) was calculated from the piston position using the equation

where s is the piston displacement (in cm), t is time (in seconds), and Ap is the area of the piston (in cm2). The value of \( \frac{\Delta s}{\Delta t} \) is the instantaneous piston velocity, which is limited to 2.54 m/s by the shaker specifications (Table 2). The instantaneous flow rate Q is a function of time t and can be expressed as

While the measured pressure difference shares the same frequency, it is delayed by a phase angle θ and can be expressed as

where ω is the frequency (rads/s), θ is the phase difference (in rads), and the items subscripted zero are the amplitudes of each variation.

The instantaneous pressure difference across the sample ΔP was then plotted as a function of the instantaneous flow rate as shown in Fig. 6. When ϕ = 0 or π/2 radians, the plot is a straight line with a positive or negative gradient, respectively. For 0 < ϕ<π/2, the plot exhibits a canted ellipse, which is symmetric about the y-axis at ϕ = π/4. This curve is a simple Lissajous figure.

a Example of measured permeability data (resulting pressure difference as a function of imposed harmonic flow rate) together with the fitted sinusoidal curve for sample B2III. b Schematic diagram showing various parameters used for calculating the permeability magnitude and phase difference. Frequency 40 Hz, phase difference 52.13°

The x–y extremes of this curve (as shown in Fig. 6b) were used to measure the amplitude of the pressure difference ΔPo and flow rate Qo. The magnitude of the dynamic permeability (ko) was then calculated using

where η is the fluid viscosity (in Pa s), A and L are the cross-sectional area and length of the sample (in cm2 and cm, respectively), k is the permeability in (mD), and a = 1000 is a constant allowing the reporting of permeability in millidarcies.

The Lissajous method was used to measure the phase difference θ between ΔPo and Qo. This is carried out by measuring the intercept on the ordinate, shown in Fig. 6b as \( y^{*} \), and then resolving the equation

The in-phase (IP) and in-quadrature (IQ) components of the dynamic permeability were calculated, respectively, as

5.4 Frequency-Dependent Streaming Potential Coefficient

Frequency-dependent streaming potential coefficient was calculated in a similar manner to that described above. In this case, the instantaneous pressure difference and measured streaming potential can be expressed, respectively, as

The magnitude of the streaming potential coefficient (Cspo) was then calculated using

The in-phase (IP) and in-quadrature (IQ) components of the streaming potential coefficient were calculated, respectively, using

Figure 7 shows the measured raw data for a small number of cycles presented as a time progression and as a ΔV/ΔP cross-plot.

a Measured streaming potential coefficient data (streaming potential as a function of imposed fluid pressure difference) together with the fitted sinusoidal curve. b Sinusoidal fits to both the streaming potential and imposed fluid pressure difference. Sample B2III, frequency 40 Hz, phase difference 52.13°

It should be noted that analysis of the raw data can also be carried out using a curve fitting approach. We have implemented this method to ascertain whether it offers a better approach. In the curve fitting method, the first step involves fitting a best-fit sinusoidal curve to the two data streams. This was carried out by implementing the sinusoidal fit MATLAB code. The result of this fitting is also shown in Fig. 7. The peak-to-peak values for the in-phase and quadrature components of the streaming potential can be obtained from the maximum values of the fitted curves, while the phase difference is calculated from the progressive zero-crossing values of the fitted curve.

Tests were carried out on synthetic data to enable us to judge the accuracy of each approach. We created sinusoidal trains of the form

where A and B are constant amplitudes, and with controlled Gaussian errors representing random measurement errors. Imposed uncertainties of ± 2.5 provided a final error in dynamic permeability of ± 5.7% and ± 5.3% for the Lissajous and sinusoidal fitting methods, respectively, and errors in the streaming potential coefficient of ± 3.9% and ± 3.5%, again for the Lissajous and sinusoidal fitting methods, respectively. The higher values for the dynamic permeability arise from the incorporation of experimental errors in the length and area of the sample and the viscosity of the process fluid. The sinusoidal method is the better of the two and has been used in all the results and error bars presented in this work. However, the Lissajous method was also fairly accurate when the means of the maximum values and ordinate crossing values for each cycle of many (> 100) cycles were used, as in this work. However important the reduction of error in the data analysis is, these errors are small compared to the experimental errors themselves, as described in the following section.

6 Initial Results

6.1 Sample Material and Supporting Measurements

Boise sandstone is a high porosity (ϕ ≈ 0.35–0.4) sandstone with an extremely high permeability (k ≈ 2 D–5 D, 1.07 × 10−12 m2–4.93 × 10−12 m2). It is isotropic and homogeneous and is composed of well-sorted sub-rounded grains in the range 200–2000 μm. The grains are predominantly quartz (80% to 90%), feldspar (albite and microcline, 7% to 10%) and some mica (muscovite, 2% to 3%) and are cemented by quartz, with overgrowths of quartz microcrystals and evidence if some feldspar digestion as well as trace amounts of iron sulphides and clays (Walker and Glover 2018).

Initial measurements were made on three samples of Boise sandstone from the same batch samples that had been used in previous steady-state streaming potential measurements (Walker and Glover 2018). Each sample was subjected to a range of background petrophysical tests, the results of which are shown in Table 3. Porosity measurements were made using helium pycnometry, by saturation with the experimental fluid, and on offcuts using mercury porosimetry. Permeability measurements were made using nitrogen at a range of different flow pressures with the results subsequently being Klinkenberg-corrected. Grain sizes were measured on disaggregated samples using laser diffractometry. The Theta Transform of Glover and Walker (2009) was used to calculate the pore radius distribution, and subsequently the methods in Glover and Déry (2010) were used to calculate the pore throat radius distribution, which was then compared against the measured value from mercury porosimetry. Table 3 also includes the measured values of fluid pH, density and viscosity during the experiment, and the calculation of the expected critical frequency obtained by using Eq. (5).

A limited number of models have been fitted to the data with different degrees of success. These models require computation of complex numbers and have been carried out by developing code in Maple 2018.

6.2 Dynamic Permeability Data

Initial dynamic permeability results as a function of frequency for each of the three samples are shown in Fig. 8 in the form of the in-phase (IP) and in-quadrature (IQ) normalised hydraulic coupling coefficient Chp. In all cases, the experimental error increases at higher frequencies. This results in the uncertainty in the critical transition frequency also increasing with frequency.

In-phase and in-quadrature hydraulic coupling coefficient data with associated uncertainties as a function of frequency for each sample. The associated best-fit Debye curves provide the values of critical frequency shown in Table 3, while the associated Packard curves are for the independently measured pore radii shown in Table 3. A better fit is possible by varying the model pore radius, and these values are also given in Table 3

The Debye relationship and the Packard model given in Eq. (2) have been fitted to the dynamic permeability data and found to describe the data very well (Fig. 8). The transition frequency obtained from the Debye curve fitting is given in Table 3. These are systematically about 3% less (− 2.84%, − 3.34% and − 2.75% for samples B1IV, B2III and B3IV, respectively) than the values predicted using independent values of pore size calculated from the measured laser diffraction grain size using the Glover and Walker (2009) method. Table 3 also shows pore sizes obtained using two different methods: first, from the critical frequency obtained from the Debye fit and using Eq. (5), and second, directly from the implementation of the Packard fit. The pore size value calculated from the Debye data agrees very well with the independently obtained values, overestimating the pore size by less than 2% (+ 1.61%, + 1.73% and + 1.52% for samples B1IV, B2III and B3IV, respectively). The Packard approach provided pore sizes which systematically underestimated the pore size by about 12% (− 14.45%, − 11.35% and − 12.18% for samples B1IV, B2III and B3IV, respectively), which may be due to a partial failure of the capillary bundle assumption which underlies this model.

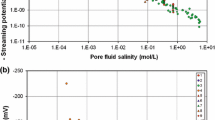

6.3 Frequency-Dependent Streaming Potential Data

Initial dynamic streaming potential coefficient (Csp) results as a function of frequency for each of the three samples are shown in Fig. 9. This data are also in the form of in-phase (IP) and in-quadrature (IQ) normalised curves. Once again, the experimental error increases with frequency which implies a greater uncertainty in any assessment of the critical transition frequency.

In-phase and in-quadrature streaming potential coupling coefficient data with associated uncertainties as a function of frequency for each sample. Neither the Debye or Packard/Reppert models fit the data well because the data is asymmetric. The Pride/Walker and Glover models provide a better fit from which the critical frequency can be measured (as shown in Table 3 together with the permeability derived from using Eq. 5)

Equations 3 and 4 have been fitted to the frequency-dependent streaming potential data, together with the Debye dispersion model (Fig. 9). The Debye and Packard/Reppert et al. models do not fit the data well. These models provide a symmetrical dispersion curve in log(ω), whereas the measured streaming potential data are clearly asymmetric. Such an asymmetry was also observed in data for Ottawa sand and glass beads made with the previous experimental apparatus (Tardif et al. 2011; Glover et al. 2012b, c). By contrast, the Pride (1994) model and its Walker and Glover (2010) simplification both provide an asymmetric curve that fits the data well in all three samples. We have fitted the Walker and Glover simplification of the Pride model to the data in each case, using independent measurements of characteristic pore size (Λ), saturation porosity (ϕ), cementation exponent (m) and steady-state permeability (kDC) to calculate \( m^{*} \) which is the only other potentially variable parameter in the equation. The results of this fitting provide estimates of the critical frequency which are given in Table 3. Fitting the Walker and Glover (2010) simplification of the Pride (1994) model to the experimental data for each of the samples gives experimental estimations of critical frequency only 2% lower than the predicted value (− 2.13%, − 2.15% and − 1.65% for samples B1IV, B2III and B3IV, respectively). The characteristic pore size can be calculated from the transition frequency of the streaming potential coefficient curves, as formalised in Eq. (5). We have calculated the characteristic pore size for each sample, and their values are also shown in Table 3. For each sample, the values of characteristic pore size fall within 1.24% of the values obtained independently by using the Glover and Walker (2009) method in laser diffraction grain size measurements (+ 1.24%, + 1.12% and + 0.95% for samples B1IV, B2III and B3IV, respectively).

While we have concentrated on the frequency-dependent part of the hydraulic and streaming potential coefficients, we also calculated the steady-state permeability and steady-state streaming potential coefficient and found them in both cases to be close to the value of Klinkenberg permeability that was measured independently using an nitrogen apparatus, and steady-state streaming potential coefficient made using the transient streaming potential coefficient apparatus that was described in Walker et al. (2014).

7 Conclusions

In this paper, we have shown that the general harmonic approach developed to measure the frequency-dependent streaming potential coefficient for sands and bead packs that was developed by Tardif et al. (2011) and Glover et al. (2012a, b) can be applied to some high permeability clastic rocks providing a specially designed apparatus is used. Specifically:

An apparatus for the measurement of the streaming potential coefficient of high permeability porous media including high porosity rocks has been designed, constructed and tested.

The apparatus can also be used to measure the dynamic permeability of high permeability porous media.

The apparatus may be used for frequencies between 1 Hz and 2 kHz, for cylindrical samples of 10 mm and lengths between 5 mm and 30 mm. The lower limit of permeability is 10 mD (9.869 × 10−15 m2), for which short samples must be used.

The quality of measurements depends critically upon removing all bubbles of gas from the apparatus.

Analysis of random experimental errors indicates that dynamic permeability can be measured to within ± 6.1%, and streaming potential coefficient to within ± 9.2%.

The apparatus has been used to obtain data on three samples of Boise sandstone. Good quality measurements were possible. The critical frequency was explicitly measureable on the high permeability Boise sandstone, which was 918.3 ± 99.4 Hz (± 9.24%) overall, but less than ± 3.4% for individual samples.

Characteristic pore radius was both calculated from the critical frequencies and compared well with independent experimental measurements. Fits of the Debye model to Chp data and the Pride model to Csp data enabled the calculation of characteristic pore size to within 2%, while fits of the Packard model to Chp data were 12% underestimated.

While the restriction for using this apparatus only on high permeability porous media strictly limits the apparatus in geosciences, these measurements may find a greater application in chemical engineering where high porosity and permeability porous media are more common.

References

Alkafeef, S.F., Alajmi, A.F.: The electrical conductivity and surface conduction of consolidated rock cores. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 309(2), 253–261 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcis.2007.02.004

Bordes, C., Jouniaux, L., Dietrich, M., Pozzi, J.P., Garambois, S.: First laboratory measurements of seismo-magnetic conversions in fluid-filled Fontainebleau sand. Geophys. Res. Lett. 33(1), L01302 (2006)

Bordes, C., Jouniaux, L., Garambois, S., Dietrich, M., Pozzi, J.P., Gaffet, S.: Evidence of the theoretically predicted seismomagnetic conversion. Geophys. J. Int. 174(2), 489–504 (2008)

Charlaix, E., Kushnick, A.P., Stokes, J.P.: Experimental study of dynamic permeability in porous media. Phys. Rev. Lett. 61(14), 1595–1598 (1988)

Cooke, C.E.: Study of electrokinetic effects using sinusoidal pressure and voltage. J. Chem. Phys. 23(12), 2299–2303 (1955)

Dimon, P., Kushnick, A.P., Stokes, J.P.: Resonance of a liquid–liquid interface. J. Phys. (Paris) 49, 777–785 (1988)

Dinariev, O.Y., Mikhailov, D.N.: Simulation of the dynamic (frequency-dependent) permeability and electrical conductivity in porous materials based on the concept of an ensemble of pores. J. Appl. Mech. Tech. Phys. 52(1), 82–95 (2011)

Glover, P.W.J.: Geophysical Properties of the Near Surface Earth: Electrical Properties. Treatise on Geophysics, Second edn, pp. 89–137. Oxford, Oxford (2015)

Glover, P.W.J.: Modelling pH-dependent and microstructure-dependent streaming potential coefficient and zeta potential of porous sandstones. Transp. Porous Media 124(1), 31–56 (2018)

Glover, P.W.J., Déry, N.: Streaming potential coupling coefficient of quartz glass bead packs: dependence on grain diameter, pore size, and pore throat radius. Geophysics 75(6), F225–F241 (2010)

Glover, P.W.J., Jackson, M.D.: Borehole electrokinetics. Leading Edge (Tulsa, OK) 29(6), 724–728 (2010)

Glover, P.W.J., Walker, E.: Grain-size to effective pore-size transformation derived from electrokinetic theory. Geophysics 74(1), E17–E29 (2009)

Glover, P.W.J., Meredith, P.G., Sammonds, P.R., Murrell, S.A.F.: Ionic surface electrical conductivity in sandstone. J. Geophys. Res. 99(B11), 21635–21650 (1994)

Glover, P.W.J., Walker, E., Jackson, M.D.: Streaming-potential coefficient of reservoir rock: a theoretical model. Geophysics 77(2), D17–D43 (2012a). https://doi.org/10.1190/GEO2011-0364.1

Glover, P.W.J., Ruel, J., Tardif, E., Walker, E.: Frequency-dependent streaming potential of porous media-part 1: experimental approaches and apparatus design. Int. J. Geophys. 2012, 1 (2012b)

Glover, P.W.J., Walker, E., Ruel, J., Tardif, E.: Frequency-dependent streaming potential of porous media-part 2: experimental measurement of unconsolidated materials. Int. J. Geophys. 2012, 17 (2012c)

Johnson, D.L., Koplik, J., Dashen, R.: Theory of dynamic permeability and tortuosity in fluid saturated porous media. J. Fluid Mech. 176, 379–402 (1987)

Jouniaux, L., Bordes, C.: Frequency-dependent streaming potentials: a review. Int. J. Geophys. 2012, 11 (2012)

Jouniaux, L., Ishido, T.: Electrokinetics in earth sciences: a tutorial. Int. J. Geophys. 2012, 16 (2012)

Jouniaux, L., Pozzi, J.P.: Streaming potential and permeability of saturated sandstones under triaxial stress: consequences for electrotelluric anomalies prior to earthquakes. J. Geophys. Res. 100, 10197–10209 (1995a). https://doi.org/10.1029/95JB00069

Jouniaux, L., Pozzi, J.P.: Permeability dependence of streaming potential in rocks for various fluid conductivities. Geophys. Res. Lett. 22, 485–488 (1995b)

Jouniaux, L., Pozzi, J.P.: Laboratory measurements anomalous 0.1–0.5 Hz streaming potential under geochemical changes: implications for electrotelluric precursors to earthquakes. J. Geophys. Res. 102, 15335–15343 (1997). https://doi.org/10.1029/97JB00955

Jouniaux, L., Zyserman, F.: A review on electro-kinetically induced seismo-electrics, electro-seismics, and seismo-magnetics for Earth sciences. Solid Earth 7(1), 249–284 (2016)

Knackstedt, M.A., Sahimi, M., Chan, D.Y.C.: Cellular-automata calculation of frequency-dependent permeability of porous media. Phys. Rev. E 47(4), 2593–2597 (1993)

Kranz, R.L., Saltzman, J.S., Blacic, J.D.: Hydraulic diffusivity measurements on laboratory rock samples using an oscillating pore pressure method. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 27, 345–352 (1990)

Liu, X., Greenhalgh, S., Zhou, B., Heinson, G.: Generalized poroviscoelastic model based on effective Biot theory and its application to borehole guided wave analysis. Geophys. J. Int. 207(3), 1472–1483 (2016)

Peng, R., Di, B., Wei, J., Glover, P.W.J., Lorinczi, P., Ding, P., Liu, Z.: The seismoelectric coupling in shale. In: 80th EAGE Conference and Exhibition 2018 Proceedings, EAGE, 11 Jun (2018a)

Peng, R., Glover, P.W.J., Di, B., Wei, J., Lorinczi, P., Ding, P., Liu, Z.: The effect of rock permeability and porosity on seismoelectric conversion. In: 80th EAGE Conference and Exhibition 2018 Proceedings. EAGE. 11 Jun 2018 (2018b)

Peng, R., Di, B., Glover, P.W.J., Wei, J., Lorinczi, P., Ding, P., Liu, Z., Zhang, Y., Wu, M.: The effect of rock permeability and porosity on seismo-electric conversion: experiment and analytical modelling. Geophys J. Int. 219(1), 328–345 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1093/gji/ggz249

Packard, R.G.: Streaming potentials across glass capillaries for sinusoidal pressure. J. Chem. Phys. 21(2), 303–307 (1953)

Pride, S.: Governing equations for the coupled electromagnetics and acoustics of porous media. Phys. Rev. B 50(21), 15678–15696 (1994)

Renner, J., Steeb, H.: Modeling of fluid transport in geothermal research. In: Freeden, W., et al. (eds.) Handbook of Geomathematics, pp. 1443–1500. Springer, Berlin (2015)

Reppert, P.M., Morgan, F.D.: Streaming potential collection and data processing techniques. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 233(2), 348–355 (2001)

Reppert, P.M., Morgan, F.D., Lesmes, D.P., Jouniaux, L.: Frequency-dependent streaming potentials. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 234(1), 194–203 (2001)

Reppert, P. M.: Electrokinetics in the Earth. Ph.D. thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (2000)

Revil, A., Glover, P.: Theory of ionic-surface electrical conduction in porous media. Phys. Rev. B Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 55(3), 1757–1773 (1997)

Revil, A., Glover, P.W.J.: Nature of surface electrical conductivity in natural sands, sandstones, and clays. Geophys. Res. Lett. 25(5), 691–694 (1998)

Revil, A., Pezard, P.A., Glover, P.W.J.: Streaming potential in porous media 1. Theory of the zeta potential. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 104, 20021–20031 (1999)

Sears, A.R., Groves, J.N.: The use of oscillating laminar flow streaming potential measurements to determine the zeta potential of a capillary surface. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 65(3), 479–482 (1978)

Sheng, P., Zhou, M.-Y.: Dynamic permeability in porous media. Phys. Rev. Lett. 61(14), 1591–1594 (1988)

Song, I., Renner, J.: Analysis of oscillatory fluid flow through rock samples. Geophys. J. Int. 170(1), 195–204 (2007)

Steeb, H.: Dynamic permeability: experimental investigations and numerical analysis in the low and high frequency regime. In: Poromechanics 2017: Proceedings of the 6th Biot Conference on Poromechanics 2017, pp. 1739–1746 (2017)

Tardif, E., Glover, P.W.J., Ruel, J.: Frequency-dependent streaming potential of Ottawa sand. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 116, 4 (2011)

Vinogradov, J., Jaafar, M.Z., Jackson, M.D.: Measurement of streaming potential coupling coefficient in sandstones saturated with natural and artificial brines at high salinity. J. Geophys. Res. 115, B12204 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1029/2010JB007593

Walker, E., Glover, P.W.J.: Characteristic pore size, permeability and the electrokinetic coupling coefficient transition frequency in porous media. Geophysics 75(6), E235–E246 (2010)

Walker, E., Glover, P.W.J.: Measurements of the relationship between microstructure, pH, and the streaming and zeta potentials of sandstones. Transp. Porous Media 121(1), 183–206 (2018)

Walker, E., Glover, P.W.J., Ruel, J.: A transient method for measuring the DC streaming potential coefficient of porous and fractured rocks. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 119(2), 957–970 (2014)

Acknowledgements

This work has been made possible thanks to funding from (i) Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) Discovery Grant Programme, and (ii) the Government of China in the form of a National Science & Technology Major Project (No. 2016ZX05007-006). The authors acknowledge the help of Jean Ruel and Eric Tardif in the early stages of the project, as well as the incisive comments from two anonymous reviewers, which have significantly improved the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Glover, P.W.J., Peng, R., Lorinczi, P. et al. Experimental Measurement of Frequency-Dependent Permeability and Streaming Potential of Sandstones. Transp Porous Med 131, 333–361 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11242-019-01344-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11242-019-01344-5