Abstract

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is the third most common cause of cardiovascular disease. Connection between high level of physical activity (PA) and the onset of VTE is unknown. We searched the literature on the possible association between PA level, especially high levels, and the risk of VTE. A systematic review was carried out to identify relevant articles on the relation between PA level and VTE. The initial search was conducted together with the Karolinska Institutet University Library in February 2018, with follow-up searches after that. In total, 4383 records were found and then screened for exclusion of duplicates and articles outside the area of interest. In total, 16 articles with data on 3 or more levels of PA were included. Of these, 12 were cohort and 4 were case-control studies. Totally 13 studies aimed at investigating VTE cases primarily, while three studies had other primary outcomes. Of the 16 studies, five found a U-shaped association between PA level and VTE risk, although non-significant in three of them. Two articles described an association between a more intense physical activity and a higher risk of VTE, which was significant in one. Nine studies found associations between increasing PA levels and a decreasing VTE risk. Available literature provides diverging results as to the association between high levels of PA and the risk of venous thromboembolism, but with several studies showing an association. Further research is warranted to clarify the relationship between high level PA and VTE.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Highlights

-

Low physical inactivity (PA) is a risk factor for venous thromboembolism (VTE).

-

Several studies but not all showed an association between high levels of PA and increased risk of VTE.

-

More studies on association between PA and VTE risk with proper methods are needed.

Introduction

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is the third most common cause of cardiovascular disease, after coronary artery disease and stroke [1]. The annual incidence of VTE in Sweden is estimated at 150–200 per 100,000 person-years and the risk increases with age [2, 3]. In Sweden, over 11,000 patients are nursed annually in hospitals because of VTE, and around 40,000 medical visits within outpatient care are due to VTE [4].

VTE can express itself in various ways, from a completely asymptomatic thrombosis to a massive lung embolization with fatal outcome. Anticoagulant treatment is effective in preventing recurrence but can cause bleeding complications [5]. There are also models to predict recurrent VTE, above all the Vienna model [6], with a higher recurrent risk among men, patients with proximal DVT or PE, and higher D-dimer levels.

Physical activity and its positive effects on good health and well-being are well established. A total of 150 min of physical activity of at least moderate intensity per week, or at least 75 min of high intensity, is recommended by the Public Health Agency of Sweden which is consistent with that from the World Health Organisation (WHO) [7]. Low levels of physical activity are associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular morbidity [8]. As regards VTE, bed rest is a known risk factor for VTE, and a sedentary lifestyle also seems to be associated with an increased VTE risk [9,10,11].

Notwithstanding the positive health effects, there are also health risks associated with PA, in particular when strenuous exercise is concerned. The occurrence of cardiovascular events and also sudden cardiac death in, for example, long-distance running is documented [12]. In a Danish study on jogging, a U-shaped association between dose of jogging and all-cause mortality was described [13]. However, it is unclear whether this type of association also applies to PA and the risk of VTE. In particular, it is unclear whether highly intense exercise, as practiced today by a growing number of recreational athletes up to high age, is a protecting factor or a risk. Furthermore, it is unclear whether VTE contributes to the momentarily increased risk of cardiovascular events during highly intense exercise, and whether such risk is related to specific sports/modes of exercise. Two earlier reviews on the association between high and low levels of PA and VTE risk concluded, that higher PA level showed lower VTE risk [9, 11], but did explore the possible higher risk of VTE with highest PA levels.

The aim of this review was to assess current knowledge on the risk of venous thromboembolism in association with high levels of physical activity as described in the literature.

Method

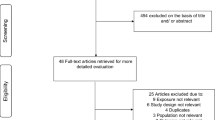

Figure 1 describes the process of article inclusion. We searched without restrictions in terms of year, or publication type in the following databases: Medline (Ovid), Embase (embase.com), and Web of Science (Clarivate Analytics), to identify relevant articles and references. The searches were conducted by two librarians at the Karolinska Institutet University Library in February 2018. The complete search strategies are available as a supplementary file. The extensive search strategy included both free-text and MeSH terms and was initially created in Medline and later adapted to the other databases with corresponding vocabularies. Reference lists of included articles were also searched for finding relevant papers, and articles citing the already included studies were identified in further Google Scholar searches. In the end it remained 32 possible articles, which we have read carefully and finally included 16 articles in our systematic review. In additional search the last four articles were found [9, 14,15,16]. If in doubt whether an article would be included, HDM and PW discussed how to judge it.

An inclusion criterion was that physical activity (PA) should be categorized at least into three levels, in order to be able to quantify risk of VTE in strenuous activity level. Thus, 5 articles with only dichotomization of PA level were excluded, and besides another 11 not quantifying PA level at all were also excluded, leaving 16 articles left. A Flow chart on inclusion and exclusion of articles is shown in supplementary files.

We also assessed the quality of the review [17], as well as the included articles. In general, the included articles were of good quality according to both reviewers. As these were observational studies, both cohort and case-control studies were found and included. We excluded one article on venous thrombosis in the upper extremity owing to low quality, as it only showed the frequency of strenuous activity among men and associated incident thrombosis [18]. In the review by Evensen et al. original follow-up data from the Tromsø study was presented [9], i.e. 1994–2013, which extends results presented in an earlier article (1994–2007) [19]. We decided to include both these papers although review articles were otherwise excluded.

Results

This systematic review included 16 articles (Table 1). Out of these, 12 were cohort and 4 were case-control studies. A total of 13 studies aimed at study VTE cases primarily, while in three other studies this was a secondary aim [20,21,22].

Of the studies, two found a statistically significant U-shaped association between physical activity level and VTE risk [20, 21], while three studies showed a non-significant U-shape, i.e. two from the Norwegian Tromsø study [9, 19], and another by Wattankit et al. [22]. One study found an association between increased level of PA and a greater risk of VTE [1].

In the article by Tsai et al. [23], two measures of physical activity were applied because of two pooled cohorts, the ARIC (Atherosclerosis Risk In Communities) study used a score and the CHS (Cardiovascular Health Study) assessing kcal/week. We choose the latter measure allowing for a better discrimination of different PA levels. In the CHS cohort (≥ 65 years) an increased level of physical activity was non-significantly associated with an increased VTE risk. However, in the article by van Stralen et al. [21], using the same CHS cohort, a significant U-shaped association was found. Different cut-offs for physical activity level were used in the analyses, and the definition of strenuous activity seemed stricter in the article by von Stralen et al. [21], than in the study by Tsai et al. [23].

Seven studies found that an increasing physical activity level was associated with a decreasing VTE risk [15, 16, 24,25,26,27,28], and one showed a non-significant association [29]. One study found divergent results for men and women, with a non-significant lower risk among women but a similar risk as the reference group among men [2].

A special topic is the possible association between strenuous arm activity and VTE. Two studies showed a slightly elevated risk of upper extremity thrombosis with strenuous muscular activity of the upper extremity [18, 30], although both studies were non-significant. However, these studies were later excluded from the review because of the insufficient graded levels of PA.

Discussion

The main finding of this systematic review is that the literature reports conflicting results regarding the association between different levels of PA and the associated risk of VTE, and especially regarding the potential risk of VTE with exercise on a high level.

While most of studies described a significantly decreasing VTE risk with increasing physical activity [15, 16, 24,25,26,27,28], also one with a non-significant association [29], another study found quite the opposite [1]. Some studies demonstrated or suggested a U-shaped association [9, 19,20,21,22]. One study found a different pattern between men and women [2], and one study found no association between PA level and VTE risk. However, as VTE may occur a long time after an exercise, a causal association and the identification of risk predictors may be difficult to establish.

Regarding levels of PA, this can be assessed in different ways, e.g. with the EPIC-PAQ suggested as suitable as a standardized measurement with 4 levels of PA [31]. For our concern a definition of strenuous levels of PA is warranted, and thus a more differentiated scale would be useful, e.g. the NOPAC with 10 categories [32], in order to be able to study the possible association between strenuous PA and incident VTE. In the study by Armstrong et al. [23], women reporting a strenuous exercise daily only comprised 3.2% of the population [33]. Categorizing samples into tertiles, quartiles or quintiles might not catch the group with the highest rate of strenuous physical activity.

There are possible mechanisms that could explain the association between strenuous PA and incident VTE. A review concluded, that long and vigorous extreme exertion causes hypercoagulability together with an augmented fibrinolysis [34], but the fibrinolytic parameters return to baseline quickly, whereas the procoagulant parameters remain elevated longer.

There are limitations with this study. Other reviews including a meta-analysis on the association between PA levels and VTE have been performed [11, 35]. However, these reviews compared low and high levels of PA in general regarding VTE risk, and not specifically very high PA levels in relation to VTE risk. We did not perform a meta-analysis, as the defined levels of PA differed largely across the studies, and especially the highest level of PA, with an obvious heterogeneity. The studies might not have identified a risk group with a very high level of physical activity and a higher VTE risk. The studies did measure physical activity level in different ways, why it could be hard to compare the different results. We decided to include different kind of studies, as our intention was to include all studies on the possible association between high levels of PA and incident VTE.

There are also several strengths. We performed a systematic search for relevant articles, and the findings in the earlier published review support that we have found relevant articles.

In conclusion, it is possible that high levels of PA could be a risk factor for VTE, but with the diverging results in the review the evidence for this is still unclear. More studies to analyse the association between high PA levels and VTE risk are needed, including an attempt to quantify possible risk level of high PA, and to try to use more standardized measurements of PA activity. Concerning the possible association between high level of PA and incident VTE a gap of evidence still remains.

References

Glynn RJ, Rosner B (2005) Comparison of risk factors for the competing risks of coronary heart disease, stroke, and venous thromboembolism. Am J Epidemiol 162(10):975–982

Johansson M, Johansson L, Lind M (2014) Incidence of venous thromboembolism in northern Sweden (VEINS): a population-based study. Thromb J 12(1):6

Wandell P, Forslund T, Danin Mankowitz H et al (2019) Venous thromboembolism 2011-2018 in Stockholm: a demographic study. J Thromb Thrombolysis 48(4):668–673

The National Board of Health and Welfare. The National Board of Health and Welfare guidelines for blood clot / venous thromboembolism 2004 [Socialstyrelsens riktlinjer för vård av blodpropp/venös tromboembolism 2004; in Swedish]. Stockholm: Socialstyrelsen; 2004

Konstantinides SV, Torbicki A, Agnelli G et al (2014) ESC guidelines on the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism. Eur Heart J 35(43):3033–3069

Eichinger S, Heinze G, Kyrle PA (2014) D-dimer levels over time and the risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism: an update of the Vienna prediction model. J Am Heart Assoc 3(1):e000467

Yrkesföreningar för fysisk aktivitet (YFA). Physical Activity in the Prevention and Treatment of Disease (FYSS in Swedish). Third edition ed. Stockholm, Läkartidningen Förlag; 2017

Cheng W, Zhang Z, Yang C et al (2018) Associations of leisure-time physical activity with cardiovascular mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 44 prospective cohort studies. Eur J Prev Cardiol 25(17):1864–1872

Evensen LH, Braekkan SK, Hansen JB (2018) Regular physical activity and risk of venous thromboembolism. Semin Thromb Hemost 44(8):765–779

Douketis JD, Iorio A (2011) The association between venous thromboembolism and physical inactivity in everyday life. BMJ 343:d3865

Kunutsor SK, Makikallio TH, Seidu S et al (2020) Physical activity and risk of venous thromboembolism: systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Eur J Epidemiol 35(5):431–442

Kim JH, Malhotra R, Chiampas G et al (2012) Cardiac arrest during long-distance running races. N Engl J Med 366(2):130–140

Schnohr P, O’Keefe JH, Marott JL et al (2015) Dose of jogging and long-term mortality: the Copenhagen City heart study. J Am Coll Cardiol 65(5):411–419

Johansson M, Johansson L, Wennberg P et al (2019) Physical activity and risk of first-time venous thromboembolism. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2047487319829310

Olson NC, Cushman M, Judd SE et al (2015) American Heart Association’s Life’s simple 7 and risk of venous thromboembolism: the Reasons for geographic and racial differences in stroke (REGARDS) study. J Am Heart Assoc 4(3):e001494

Kim J, Kraft P, Hagan KA et al (2018) Interaction of a genetic risk score with physical activity, physical inactivity, and body mass index in relation to venous thromboembolism risk. Genet Epidemiol 42(4):354–365

Shea BJ, Grimshaw JM, Wells GA et al (2007) Development of AMSTAR: a measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol 7:10

Martinelli I, Cattaneo M, Panzeri D et al (1997) Risk factors for deep venous thrombosis of the upper extremities. Ann Intern Med 126(9):707–711

Borch KH, Hansen-Krone I, Braekkan SK et al (2010) Physical activity and risk of venous thromboembolism. Tromso Study Haematol 95(12):2088–2094

Armstrong ME, Green J, Reeves GK et al (2015) Frequent physical activity may not reduce vascular disease risk as much as moderate activity: large prospective study of women in the United Kingdom. Circulation 131(8):721–729

van Stralen KJ, Doggen CJ, Lumley T et al (2008) The relationship between exercise and risk of venous thrombosis in elderly people. J Am Geriatr Soc 56(3):517–522

Wattanakit K, Lutsey PL, Bell EJ et al (2012) Association between cardiovascular disease risk factors and occurrence of venous thromboembolism. A time-dependent analysis. Thromb Haemost 108(3):508–515

Tsai AW, Cushman M, Rosamond WD et al (2002) Cardiovascular risk factors and venous thromboembolism incidence: the longitudinal investigation of thromboembolism etiology. Arch Intern Med 162(10):1182–1189

Bergendal A, Bremme K, Hedenmalm K et al (2012) Risk factors for venous thromboembolism in pre-and postmenopausal women. Thromb Res 130(4):596–601

Lindqvist PG, Epstein E, Olsson H (2009) The relationship between lifestyle factors and venous thromboembolism among women: a report from the MISS study. Br J Haematol 144(2):234–240

Sidney S, Petitti DB, Soff GA et al (2004) Venous thromboembolic disease in users of low-estrogen combined estrogen-progestin oral contraceptives. Contraception 70(1):3–10

van Stralen KJ, Le Cessie S, Rosendaal FR et al (2007) Regular sports activities decrease the risk of venous thrombosis. J Thromb Haemost 5(11):2186–2192

Ogunmoroti O, Allen NB, Cushman M et al (2016) Association between Life’s simple 7 and noncardiovascular disease: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. J Am Heart Assoc 5(10)

Lutsey PL, Virnig BA, Durham SB et al (2010) Correlates and consequences of venous thromboembolism: the Iowa Women’s health study. Am J Public Health 100(8):1506–1513

Blom JW, Doggen CJ, Osanto S et al (2005) Old and new risk factors for upper extremity deep venous thrombosis. J Thrombosis Haemostasis 3(11):2471–2478

Peters T, Brage S, Westgate K et al (2012) Validity of a short questionnaire to assess physical activity in 10 European countries. Eur J Epidemiol 27(1):15–25

Borch KB, Ekelund U, Brage S et al (2012) Criterion validity of a 10-category scale for ranking physical activity in Norwegian women. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 9:2

Huxley RR (2015) Physical activity: can there be too much of a good thing? Circulation 131(8):692–694

Kicken CH, Miszta A, Kelchtermans H et al (2018) Hemostasis during extreme exertion. Semin Thromb Hemost 44(7):640–650

Evensen LH, Isaksen T, Braekkan SK et al (2019) Physical activity and risk of recurrence and mortality after incident venous thromboembolism. J Thromb Haemost 17(6):901–911

Funding

Open Access funding provided by Karolinska Institute.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Danin-Mankowitz, H., Ugarph-Morawski, A., Braunschweig, F. et al. The risk of venous thromboembolism and physical activity level, especially high level: a systematic review. J Thromb Thrombolysis 52, 508–516 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11239-020-02372-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11239-020-02372-5