Abstract

We may think that bullying is a childish behaviour that is left behind on finishing school, or that universities and colleges are too cultured and intellectual as institutions to have room for such behaviour, but these hopes are far from the truth. The research evidence shows that bullying of all kinds is rife in higher education. Indeed, it seems likely that the peculiar nature of higher education actively encourages particular kinds of bullying. This article provides a review of the research on bullying in higher education, considering what this shows about its meaning, extent and nature, and reviews the issues that have been identified and possible solutions to them. It concludes that, while there is much that higher education institutions need to do to respond effectively to bullying, revisiting their traditions and underlying purposes should support them in doing so.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

It would be nice to think that bullying was a childish behaviour that we left behind on finishing school, or that universities and colleges were too cultured and intellectual as institutions to have room for such behaviour, but these hopes are far from the truth. Even though this topic has only attracted the attention of higher education researchers relatively recently, having picked it up from research into bullying in schools and workplaces, the research evidence shows that bullying of all kinds is rife in higher education. Indeed, it seems likely that the peculiar nature of higher education actively encourages particular kinds of bullying.

The purpose of this article is to explore and examine the research evidence to see what it reveals about the extent and nature of bullying in higher education, the wider issues that this raises, and the possible solutions that have been put forward, trialled and evaluated. The article aims to provide a synopsis of the state of play regarding bullying in higher education at the time of writing – 2023 – which should prove useful to both future researchers and policy-makers in assessing whether and what progress has been made.

As this article presents a systematic review of the research literature on bullying in higher education, it is not organised in a typical or conventional fashion. The next section outlines the methodological approach taken. It is followed by sections that consider the meaning of bullying, the particular context of higher education, the extent of bullying in higher education, and its varied nature. The issues and possible solutions raised in the literature are then discussed, before some conclusions are reached.

Methodology

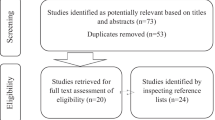

Methodologically, the article makes use of the techniques of systematic review (Jesson et al., 2011; Tight, 2021; Torgerson, 2003), an approach that seeks to identify, analyse and synthesize all of the research that has been published on a particular topic – in this case, bullying in higher education. In practice, of course, some limits have to be set on the scope of a systematic review, most notably in terms of the language of publication (in this case confined to English), the date of publication and the accessibility of published articles (all available articles, books and other publications identified were examined).

Databases – Google Scholar, Scopus and Web of Science – were searched using keywords – ‘bullying’, ‘higher education’, ‘university’, ‘college’ and related terms—to identify potentially relevant articles, books and reports that had been published on the topic. Those identified were then accessed (mostly through downloads) and examined, and retained for further analysis if they proved to be relevant. The reference lists in the articles and reports were checked for other potentially relevant sources to follow up that had not been initially identified.

These searches reveal an upswelling of interest in bullying in higher education over the last 20 years. For example, a search carried out on Scopus on 22/6/23 identified 698 articles with the words ‘bullying’, ‘higher’ and ‘education’ in their titles, abstracts or keywords, 48 of which had those three words in their titles, indicating a likely focus on the topic of interest. Similar searches using ‘bullying’ and ‘university’ identified 1361 (113) articles, while ‘bullying’ and ‘college’ found 593 (57) articles. This is a substantial and growing body of literature.

The interest in researching bullying in higher education, like the incidence of bullying, is also global in nature. While the focus on English language publications meant that the articles identified were mainly from English-speaking countries like Australia, Canada, the United Kingdom and the United States, articles were also found from researchers based in countries on all continents. Within Europe, researchers from Finland (e.g. Björklund et al., 2010; Malik & Björkqvist, 2019; Meriläinen et al., 2016; Oksanen et al., 2022; Pörhölä et al., 2020) and Greece (e.g. Giovaziolas & Malikiosi-Loizos, 2016; Kokkinos et al., 2016; Spanou et al., 2020) have shown a strong interest in the topic. Other countries where bullying in higher education has been the subject of research include China (Su et al., 2022; Zhao et al., 2022), India (Kaur & Kaur, 2023; Sinha & Bondestam, 2022), Pakistan (Ahmed et al., 2022), South Africa (Badenhorst & Botha, 2022), Spain (Yubero et al., 2023), Turkey (Akbulut & Eristi, 2011) and the United Arab Emirates (Al-Damarki et al., 2022).

With so many publications focusing on bullying in higher education it is essential to be selective in choosing which ones to reference. In part this can be achieved by only referring to examples of the output of prolific authors, and by choosing representative or the most recently published articles on particular issues. Ultimately, however, the judgement on which publications to reference was one of quality or significance; in some cases this was evidenced by the number of times a publication was cited by others, while in others it came down to personal judgement (helped, in problematic cases, by discussion with colleagues).

The analysis presented in the remainder of this article is based on the 74 key articles selected in this way, which are indicated by an asterisk (*) in the references list: 80% (59) of these have been published since 2015.

Meaning of Bullying

Like many key terms, there is no generally accepted definition of what bullying is. It makes sense, therefore, to examine a few of the definitions available to see what they include and how they differ. Here we will compare three definitions given by national organisations—in the UK, Australia and the USA – with a keen interest in the topic.

In the UK, the Anti-Bullying Alliance defines bullying as ‘the repetitive, intentional hurting of one person or group by another person or group, where the relationship involves an imbalance of power. It can happen face to face or online’ (www.anti-bullyingalliance.org.uk). There are four key elements in this definition. Two of these, that bullying may involve individuals or groups, or may be face-to-face or online, seem highly pragmatic. However, the other two, that bullying is necessarily repetitive and intentional, and that it involves an imbalance of power, are questionable. Bullies may not, at least initially, know what they are doing, and one incident may be more than enough for those being bullied. And, as social scientists should be aware, power is not a simple, unidirectional force: those lower down the hierarchy may also bully those higher up.

From Australia, the National Centre Against Bullying offers a slightly longer explanation:

Bullying is an ongoing and deliberate misuse of power in relationships through repeated verbal, physical and/or social behaviour that intends to cause physical, social and/or psychological harm. It can involve an individual or a group misusing their power, or perceived power, over one or more persons who feel unable to stop it from happening. Bullying can happen in person or online, via various digital platforms and devices and it can be obvious (overt) or hidden (covert). (www.ncab.org.au)

This definition usefully introduces a distinction between overt and covert bullying, and nuances the point about power by referring to perceived power. It does, though, repeat the assertion that bullying is always intentional or deliberate, as well as introducing the debatable point that the bullied are unable to do anything about it.

Taking a third example, the American Psychological Association defines bullying in the following way:

Bullying is a form of aggressive behavior in which someone intentionally and repeatedly causes another person injury or discomfort. Bullying can take the form of physical contact, words, or more subtle actions. The bullied individual typically has trouble defending him or herself and does nothing to “cause” the bullying. Cyberbullying is verbally threatening or harassing behavior conducted through such electronic technology as cell phones, email, social media, or text messaging. (www.apa.org/topics/bullying)

This definition usefully relates bullying to other unpleasant practices, in this case aggression, harassment and threatening behaviour. Reading the literature more widely identifies a whole range of other cognate or more specialised practices, including hazing, incivility, intimidation, mobbing, stalking and victimization, as well as what is now termed cyberbullying (i.e. bullying online). Bullying may also shade into, or overlap with, other behaviours, such as banter and humour (Buglass et al., 2021), or be labelled differently: e.g. as hostile and intimidating behaviour (Sheridan et al., 2023).

The American Psychological Association definition also gives attention to the bullied as well as the bully, suggesting that they bear no blame for the bullying (which might not always be the case) and that they have trouble defending themselves. There are, of course, many more definitions of bullying available, but the three used here adequately cover the main points and issues.

Drawing elements from these definitions together, then, presents a picture of bullying as unpleasant behaviour committed by an individual or group on another individual or group. The bullying may take a variety of forms, be face-to-face or online, overt or covert, one-off or repetitive, and unintentional or deliberate. The bully may use whatever power they have to harass and intimidate the bullied. The bullied suffers physical, psychological and/or reputational damage, and finds it difficult to defend themselves.

Research into bullying in higher education clearly developed from research into bullying in schools (e.g. Alvarez-Garcia et al., 2015; Cretu & Morandau, 2022; Gaffney et al., 2019; Moyano & Sanchez-Fuentes, 2020; Zych et al., 2021) and workplaces (e.g. Bartlett & Bartlett, 2011; Einarsen et al., 2020; Feijo et al., 2019; Hoel et al., 2001; Nielson & Einarsen, 2018); which are both of longer standing, and where a number of systematic reviews have already been carried out. Indeed, part of the interest in bullying in higher education is in assessing whether it translates directly from the experience of bullying in school (for both the bullies and the bullied), and in examining whether higher education, as a particular kind of workplace, attracts particular bullying behaviours. We will address the latter next.

The Particular Context of Higher Education

Higher education is, indeed, a particular kind of workplace. This manifests itself in several interconnected ways. For a start, like most other workplaces, it is hierarchical, with different grades of academic and other staff. Yet it is also hierarchical beyond the employing institution, with academics operating within the networks of their disciplines and sub-disciplines, nationally and internationally. Academic staff have, therefore, split loyalties and responsibilities.

Within the intersecting hierarchies of institution and discipline there operates the principle of ‘academic freedom’, albeit constrained by other expectations and responsibilities. In its ideal state, each academic member of staff is seen as having the freedom to determine what they teach and how they teach it, as well as what they research and how they research it. Of course, it rarely works quite like that in practice, particularly when it comes to teaching, which is today a much more collective and large-scale activity, and constrained by the need to receive good evaluations and the recognition of professional bodies. Research often depends upon gaining specific funding, so is constrained by the funds available and the priorities of funding organisations.

Academic life and careers are also built upon competition. To build a successful academic career, each academic needs to get their name known, even if only within a relatively small field: through conference presentations, through article and book publication, through successfully obtaining research grants. Each of these activities, as well as the gaining of employment and promotion, involves peer review, when a small number of academic peers are asked to make an assessment of your worthiness (Tight, 2022).

Critique is at the heart of these activities, in what is effectively a zero-sum game (i.e. there are only so many posts, research grants and publication spots available at any one time). Academics may get their name known not so much for their own work but for their critique of others’ work, and what may be thought of as fair criticism by one academic may be interpreted as an effort to destroy their reputation (as bullying in other words) by another.

Certain academic relationships – notably that between a research student and their supervisor (Cheng & Leung, 2022; Grant, 2008), but also between junior and senior members of academic staff working in the same area/topic – have traditionally been characterised as master/servant, or even master/slave. The dominant party – the supervisor or the senior academic – tells the junior party what to do and then assesses how well they have done it. Even today these may be strong power relationships, and may last for years.

However, at the level of the undergraduate student, where a similar kind of relationship would historically have been carried over from school, with students not allowed to challenge the academic judgements of their lecturers and professors, practices are changing. The increased privatisation of higher education, with students required to pay substantial fees, has led to a growing recognition of the student as a customer (indeed, the prime customer), with all of the rights that customers have in other circumstances.

All of these structures, practices and assumptions, and the ways they are changing and adapting to accommodate contemporary policies and expectations, would seem to offer plentiful opportunities for different kinds of bullying to take place. In short, higher education is a near perfect environment for bullying; yet, it is also a near perfect environment for the denial of bullying. Accusations of bullying may be dismissed as fair comment or ‘the way we do things around here’, with the person(s) making the accusations themselves accused of bullying those they accuse by making unwarranted complaints.

For bullying is a matter of perception, and not just in higher education but more generally as well. So anyone who feels that they are being bullied and wishes to do something about it will have to engage with a process – of formal complaint, investigation and hopefully resolution – that will take time, be semi-public and effect their working relationships. Neither the bullied not the perceived bully are likely to come out of this process with their reputation enhanced.

Extent of Bullying in Higher Education

Many attempts have been made to estimate the extent of bullying in higher education. Focusing on staff, Keashly and Neuman (2013) give the following figures:

the estimated prevalence of bullying varies depending on the nature of the sample, the operationalization of the construct, the timeframe for experiences, and the country in which the research was conducted. The rates of bullying range from 18% to almost 68%, with several studies in the 25%-35% range. These rates seem relatively high when compared to those noted in the general population, which range from 2%-5% in Scandinavian countries, 10%-20% in the UK, and 10%-14% in the United States. (pp. 10-11; see also Keashly & Neuman, 2010)

These figures are, indeed, high, suggesting that most people working in higher education should have direct – as bully, bullied or bystander (and many of us will, of course, have performed in two or more of these roles) – or indirect, through formal roles or relationships, experience of bullying. Indeed, the estimates are so high that we might speculate that, if you are working in higher education and are not being bullied, then you’re highly likely to be either doing the bullying (whether you recognise it or not) or at least aware that bullying is going on.

In a later work synthesizing the international survey evidence, Keashly (2019) confirms this interpretation:

Using the 12-month framework, approximately 25% of faculty will identify as being bullied. Adding in the witnessing data, the research suggests that 50–75% of faculty will have had some exposure to bullying in the prior 12 months. Extending the timeframe to career, it appears that faculty who have no exposure are in the minority! Further, bullying of faculty is notable for its duration. There is also evidence that rates of bullying differ cross-nationally and institutionally, suggestive of sociocultural influences. (p. 39)

Similar conclusions may be reached regarding non-academic staff working in higher education, though they have been much less studied. Thus, one American study of higher education administrators noted that: ‘Participants from 175 four-year colleges and universities were surveyed to reveal that 62% of higher education administrators had experienced or witnessed workplace bullying in the 18 months prior to the study’ (Hollis, 2015, p. 1).

The estimates for students also suggest that a significant minority are directly involved in bullying as bully or bullied. In the USA, Lund and Ross (2017) note that:

Prevalence estimates varied widely between studies, but on average about 20–25% of students reported noncyberbullying victimization during college and 10–15% reported cyberbullying victimization. Similarly, approximately 20% of students on average reported perpetrating noncyberbullying during college, with about 5% reporting cyber perpetration. (p. 348)

In a four-nation comparative study, Pörhölä et al (2020) draw particular attention to variations in bullying rates amongst students and staff between countries:

The overall rates of bullying victimization and perpetration between students were the highest in Argentina, followed by the USA, Finland, and finally Estonia. However, victimization by university personnel was reported the most in Estonia, followed by Argentina, the USA, and Finland. (p. 143)

We might also, though the data is mostly not available, expect that bullying rates would vary between disciplines and departments (Bjaalid et al., 2022), from institution to institution, and in terms of individuals’ demographic characteristics (age, class, gender, ethnicity, sexual orientation, etc.).

The Nature of Bullying in Higher Education

Most of the studies on bullying in higher education that have been identified relate to either bullying amongst academic staff or amongst students. There are a much more limited number of studies concerning bullying amongst professional, administrative or support staff in higher education. More recently, a related literature has grown on cyberbullying.

Bullying amongst academic staff is portrayed as being mainly obstructional or reputational in nature: ‘Of all the types of bullying discussed in the literature, the behaviors most frequently cited in academia involve threats to professional status and isolating and obstructional behavior (i.e., thwarting the target’s ability to obtain important objectives)’ (Keashly & Neuman, 2010, p. 53). After all, (some) academics are regularly involved in making decisions that impact upon other academics; academic life is judgemental and discriminatory. These decisions may relate to almost any aspect of academic life, from teaching allocations and course responsibilities, to promotions, publication and research grants, to the seemingly mundane but critical issues of office space and car parking.

Bullying impacts on some groups of academics more than others; in particular, and unsurprisingly, on the marginalized: ‘academic culture facilitates the marginalization of particular social identity groups… this marginalization is a reason for higher rates of bullying among gender, racial and ethnic, and sexual identity minorities in academe’ (Sallee & Diaz, 2013. p. 42). This impact is not, of course, confined to higher education.

Bullying amongst academic staff is also believed to be changing in nature, becoming somewhat more subtle as grievance and appeal procedures are overloaded with complaints:

a shift in negative higher education workplace behaviour is occurring. This change primarily results in the well-defined and identified practice of bullying being replaced with victims enduring the accumulated impact of acts of varied disrespect such as negative comments, under the breath comments, intentionally misinterpreting instructions or spreading rumours, collectively known as incivility. (Heffernan & Bosetti, 2021, p. 1; see also Higgins, 2023)

The evidence shows that bullying appears to work both ways, bottom up as well as top down. Thus, deans, who oversee faculties or groups of departments and are a key part of higher education’s middle management, have been identified as particularly subject to bullying: ‘a majority of deans currently experience regular acts of bullying or incivility… Many deans believe that an inherent part of their role is that they will be bullied, and as such, part of their role is to deal with these actions’ (Heffernan & Bosetti, 2021, p. 16). It might be expected, then, that heads of department would have a similar experience – bullied from above to meet institutional targets and from below by individual academics seeking to get their own way – but this does not appear to have been the direct object of research (yet).

One study that focused on the experience of support staff (i.e. non-academic staff) in one English university (Thomas, 2005) found that 19 of 42 respondents had experienced bullying within the last two years, whilst 17 had witnessed colleagues being bullied:

The top four bullying tactics ranked in frequency of reporting were undue pressure to reduce work, undermining of ability, shouting abuse, and withholding necessary information. When bullying occurred it was likely to be by a line manager. (p. 273)

From a North American context, where support staff are more usually termed professional staff, Fratzl and McKay (2013) make the point that they are ‘sandwiched between students and academics who may display aggressive behavior in order to deal with threats and meet their needs’ (2013, p. 70). Given these added pressures, it is critical that such staff are well supported.

For students, bullying may most commonly be carried out by other students, but also by academic staff. Blizard (2019), however, shows that the opposite, student-on-staff bullying, is also common. The majority, 22, of her 36 staff respondents in a Canadian university reported that they had experienced cyberbullying by students.

In the Spanish context, Gómez-Galán et al. (2021) identify the dominant form of student-on-student bullying as relational, as opposed to physical or verbal, and portray this as part of a continuing lifetime experience:

Relational victimization, which manifests itself through defamation, social exclusion, or denigration, persists in the university environment. Moreover, it does so mainly because of a pattern of relational violence that is repeated from the compulsory education stage… It constitutes what we call “the spiral of relational violence”—victimization which runs throughout the student’s life with psychological repercussions that can continue into adulthood, especially in the workplace. (p. 10)

The experience of being bullied, and of being a bully, may be deeply ingrained and lifelong (Manrique et al., 2020).

In a comparative study of students in China and Germany, Lin et al (2020) looked at the roles of social support, resilience and self-efficacy in mediating between bullying behaviours and mental health: ‘It was found that in both countries, higher victimization frequency was associated with lower levels of social support, personal resilience, and self-efficacy, which in turn predicted poorer mental health’ (p. 1). This is, of course, what you would expect.

As with academic staff, bullying amongst students is more often targeted at the less powerful and marginalized. Simpson and Cohen (2004) argue for the gendered nature of bullying, noting that ‘While sexual harassment is ‘overtly’ gendered, bullying also needs to be seen as a gendered activity — although at a different, and perhaps more deep-seated, level’ (p. 183). Faucher et al. (2019) confirm this pattern for cyber-bullying, while a recent systematic review carried out by Bondestam and Lundqvist (2020) found that, on average, one out of four female students reported sexual harassment.

A survey of students (n = 414) in one Australian university found that non-heterosexual students were much more likely (30% to 13%) to report bullying than heterosexual students (Davis et al., 2018). Homophobic and transphobic bullying of students is a concern in both face-to-face (Clark et al., 2022; Koehler & Copp, 2021; Rivers, 2016) and online (Pescitelli, 2019) settings.

There is also some evidence that students (and staff) working in particular disciplines, such as medicine (Björklund et al., 2020; Seabrook, 2004), are more likely to experience bullying. Such professional disciplines are clearly linked to particular kinds of workplaces, within which placements for training will be based. A greater incidence of bullying may also occur in particular kinds or levels of study; thus, the research student experience might seem to lend itself to staff-on-student bullying, but has been little researched from this perspective (Aziz, 2016).

Cyber-bullying in higher education is now being increasingly studied. In an international collection, Faucher et al. (2019) report the incidence of cyberbullying amongst students varying between 3% in Japan and 46% in Chile. They use the term ‘contra-power harassment’ to refer to cyberbullying of staff by students.

Other, nationally focused, studies have noted the relationship between cyberbullying and victimisation in Turkey, with some victims later becoming bullies (Akbulut & Eristi, 2011), identified psychological security, loneliness and age as predictors of cyberbullying in Saudi Arabia (Al Qudah et al., 2020), correlated cyberbullying with students’ belief in a just world in Germany (Donat et al., 2022), and linked the experience of cyberbullying to depression, anxiety, paranoia and suicidal feelings in the USA (Schenk & Fremouw, 2012).

Simmons et al. (2016) prefer the stronger term cyber-aggression to cyberbullying, and note its incidence among the members of American sororities and fraternities, where ‘racism is a theme that undergirds much of the online aggression’ (p. 108). Lee et al. (2022) examine the role of parental care and family support in moderating cyberbullying at an American university during the Covid-19 pandemic lockdown, when the vast majority of higher education provision went online.

Issues and Solutions

As well as examining the nature and extent of bullying in higher education, researchers have sought to better understand the issues it raises and to put forward possible solutions to it. One key issue that has attracted research is the relationship between bullying at school and bullying in higher education. Pörhölä (2016) reviews the evidence showing that both bullying and being bullied are fairly stable experiences throughout school, and then commonly continue into higher education, though the identities of the people being bullied and those doing the bullying may, of course, change. Young-Jones et al (2015) confirm these findings in the American context, and note its consequences:

students are susceptible to bullying after high school, and the effects can negatively impact college life, academic motivation, and educational outcomes. In addition, past victimization can cause academic difficulties for college students, even after the harassment has ceased. (p. 186)

Another key issue researched – turning the focus away from students and towards academics – has been the relation between bullying and the contemporary, neoliberal university. Zabrodzka et al. (2011) report on the findings of a collective biography group of academics based in the Czech Republic, Iran and Australia. They concluded that ‘bullying is co-implicated in, and justified by, the alleged need for control and improvement of our performance’ (p. 717).

In a similar study, based in Sweden, Zawadski and Jensen (2020) present their findings from a co-authored analytic autoethnography, arguing that: ‘Academics in contemporary universities have been put under pressure by the dominance of neoliberal processes, such as profit maximization, aggressive competitiveness, individualism or self-interest, generating undignifying social behaviours, including bullying practices’ (p. 398).

Of course, academics are not the only workers finding themselves under increasing pressure today. The particular nature of higher education can, however, serve to channel those pressures in a more aggressive, bullying, way.

Nelson and Lambert (2001) focus on how academic bullies get away with it, identifying a series of neutralization or normalization techniques that deflect attention away from themselves and towards those they bully:

appropriation and inversion, in which accused bullies claim victim status for themselves; evidentiary solipsism, in which alleged bullies portray themselves as uniquely capable of divining and defining the “true” meaning-structure of events; and emotional obfuscation, which takes the form of employing symbols and imagery that are chosen for their perceived ability to elicit an emotional response on the part of an academic audience. (p. 83)

With these kinds of tactics available, it would be little wonder if, in a sector of work where reputation is all important, most victims of bullying chose not to formally pursue grievances (but, of course, we don’t have this data).

Turning to the research on possible solutions to bullying in higher education, a significant amount of attention has been devoted to examining institutional policies (e.g. Barratt-Pugh & Krestelica, 2019; Campbell, 2016; Harrison et al., 2020, 2022). Thus, in a relatively early, and small-scale, study conducted in an English further/higher education college, Hughes (2001) focused on identifying examples of good practice for dealing with bullying of students. He came up with an extensive list:

immediate action; good communication; informal discussions; mediation; giving a talk to a tutor group; trying not to use student nicknames; moving students to other teaching groups; choosing groups for students to work in; including students in groups which are excluding them; use of subtlety; putting complaints into writing; making students aware of their actions; and making students aware of the boundaries of acceptable behaviour (p. 12)

In a more recent study, Vaill et al., (2020; see also Vaill et al., 2023) examined the student anti-bullying policies of 39 Australian universities, concluding that: ‘The overall paucity of information and consistency, as well as the poor user-friendliness of many of the documents, highlights the need for changes to be made’ (p. 1262).

An American study focused on the bullying of staff examined 276 faculty codes of conduct in the context of the first amendment of the American constitution. This also concluded that current arrangements were far from satisfactory: ‘higher education institutions should change their Faculty Codes of Conduct so bullying is defined as a distinctive form of harassment, provide faculty and staff clear communications regarding how to define bullying, and offer guidance for both targets and bystanders of workplace bullying’ (Smith & Coel, 2018, p. 96).

After providing a psycho-social-organizational analysis of the problem of faculty-on-faculty bullying in the USA, Twale (2018), like Hughes, comes up with a list of ‘practical remedies’. Her list is, however, rather longer, covering a total of 20 bullet-pointed pages (pp. 171–190). Her ‘practical remedies’ include suggestions for promoting physical and psychological health and well-being; promoting social interaction, professionalism and support; considering institutional obligations; providing institutionally sponsored training and development; giving attention to institutional values, beliefs and attitudes; and using administrative intervention strategies.

Bullying, and dealing with it effectively, is a complex and far-reaching business.

Conclusion

A number of general conclusions may be drawn from this review of research into bullying in higher education.

First, and most fundamentally, bullying is clearly a major problem in higher education. It is extensive, continuing, complex and arguably endemic. It involves both students and staff (academic and non-academic) and deserves much more attention.

Second, its complexity is increased by the varied dimensions in which higher education staff and, to a lesser extent, students, operate. Thus, they not only work within a particular course, department, faculty and institution, but also practice their discipline or sub-discipline nationally and internationally. Given the global nature of the higher education enterprise, and the multicultural character of many universities and colleges, we may also add to this complexity the variations in national and sub-national cultures and assumptions.

Third, bullying is a very broad and inclusive term, which includes behaviours that are now more usually discussed in the more specialised languages of, for example, sexism, racism, anti-semitism, homophobia or transphobia (i.e. affecting those who may feel particularly marginalised). To focus on these more specialised areas, however, risks ignoring the many, more commonplace types of bullying that take place, for example, between straight white men and/or straight white women.

Fourth, the role of perception in bullying has to be acknowledged. Just as the bullied have to recognise that they are being bullied for bullying to be identified, so the bullies may not realise that that is what they are doing until they are called out, and, even then, they may still not accept it for what it is. This also applies, of course, to those – individuals, departments, committees and institutions – called upon to rule on and resolve alleged instances of bullying. Naturally enough, this makes bullying so much more difficult to deal with.

Fifth, and finally, there is the question alluded to earlier in this article; namely, does higher education encourage particular kinds of bullying? Here, we need to acknowledge that universities and colleges are a particular kind of institution, to a considerable extent closed off from the outside world, within which other rules apply and high-stakes decisions affecting individuals’ futures are routinely taken. When we add in the additional pressures imposed by managerialism and neoliberalism, it is little wonder that the scope for bullying is enhanced.

It would be nice to be able to draw out from all of this research some key lessons which we all might usefully learn, and which would go some significant way to resolving the issue of bullying in higher education. But, of course, it is not that simple. Some of the key lessons to be learnt have just been summarised, and, as indicated, many institutions and individuals have set out recommendations for improving practice. And, yet, bullying remains rife in higher education across the globe.

Perhaps, instead, we also need to re-emphasise the cultural and intellectual traditions of higher education. As well as clamping down hard on all kinds of bullying, higher education institutions could usefully stress their expansive and liberatory functions. These include encouraging and supporting learning in all areas and on all topics; extending a warm welcome to all who can benefit from their provision and resources; and bringing people together to cooperate in expanding knowledge and understanding.

The university is a great institution, and one of the longest lasting that humans have created. While it has changed and expanded massively over the years, it still holds onto cherished ideas of, for example, intellectual freedom, fairness and scholarship. We need to strengthen these if we are to have any hope of overcoming bullying.

References

The articles asterisked (*) were identified by the systematic review.

*Ahmed, B., Yousaf, F., Ahmad, A., Zohra, T., & Ullah, W. (2022). Bullying in Educational Institutions: college students’ experiences. Psychology, Health and Medicine,https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2022.2067338

*Akbulut, Y., & Eristi, B. (2011). Cyberbullying and Victimisation among Turkish University Students. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 27(7), 1155-1170.

*Al Qudah, M. F., Al-Barashdi, H. S., Hassan, E. M. A. H., Albursan, I. S., Heilat, M. Q., Bakhiet, S. F. A., & Al-Khadher, M. A. (2020) Psychological Security, Psychological Loneliness and Age as the Predictors of Cyber-Bullying among University Students. Community Mental Health Journal, 56, 393-403.

*Al-Darmaki, F., Al Sabbah, H., & Haroun, D. (2022) Prevalence of Bullying Behaviors among Students from a National University in the United Arab Emirates: a cross-sectional study. Frontiers in Psychology, 13(768305), 12.

*Álvarez-García, D., García, T., & Núñez, J. C. (2015) Predictors of School Bullying Perpetration in Adolescence: a systematic review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 23, 126-136.

*Aziz, R. (2016). The Research Student Experience. pp. 21-32 in Cowie, H, and Myers, C-A (eds) Bullying Among University Students: cross-national perspectives. Abingdon, Routledge.

*Badenhorst, M., & Botha, D. (2022) Workplace Bullying in a South African Higher Education Institution: academic and support staff experiences. South African Journal of Human Resource Management, 20(0), a1909, 13.

*Barratt-Pugh, L, and Krestelica, D (2019) Bullying in Higher Education: culture change requires more than policy. Perspectives: Policy and Practice in Higher Education, 23(2–3), 109–114.

*Bartlett, J., & Bartlett, M. (2011). Workplace Bullying: an integrative literature review. Advances in Developing Human Resources, 13(1), 69-84.

*Bjaalid, G., Menichelli, E., & Liu, D. (2022) How Job Demands and Resources relate to Experiences of Bullying and Negative Acts among University Employees. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19, 8460, 16pp.

*Björklund, K., Häkkänen-Nyholm, H., Sheridan, L., & Roberts, K. (2010) The Prevalence of Stalking among Finnish University Students. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 25(4), 684-698.

*Björklund, C., Vaez, M., & Jensen, I. (2020) Early Work-Environmental Indicators of Bullying in an Academic Setting: a longitudinal study of staff in a medical university. Studies in Higher Education,https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2020.1729114

*Blizard, L. (2019). Student-to-Faculty Targeted Cyberbullying: the impact on faculty. pp. 126-138 in Cassidy, W, Faucher, C, and Jackson, M (eds) Cyberbullying at University in International Contexts. New York, Routledge.

Bondestam, F., & Lundqvist, M. (2020). Sexual harassment in higher education: a systematic review. European Journal of Higher Education, 10(4), 397–419.

*Buglass, S. L., Abell, L., Betts, L. R., Hill, R., & Saunders, J. (2021) Banter Versus Bullying: a university student perspective. International Journal of Bullying Prevention, 3, 287-299.

*Campbell, M. (2016). Policies and Procedures to Address Bullying at Australian Universities. pp. 157-171 in Cowie, H, and Myers, C-A (eds) Bullying Among University Students: cross-national perspectives. Abingdon, Routledge.

*Cheng, M., & Leung, M-L. (2022). “I’m not the Only Victim…” Student perceptions of exploitative supervision relation in doctoral degree. Higher Education, 84, 523-540.

*Clark, M., Kan, U., Tse, E. J., & Green, V. A. (2022) Identifying Effective Support for Sexual Minority University Students who have experienced Bullying. Journal of Gay and Lesbian Social Services, https://doi.org/10.1080/10538720.2022.2057381

*Cretu, D., & Morandau, F. (2022). Bullying and Cyberbullying: a bibliometric analysis of three decades of research in education. Educational Review,https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2022.2034749

*Davis, E. M., Campbell, M. A., & Whiteford, C. (2018) Bullying Victimization in Non-Heterosexual University Students. Journal of Gay and Lesbian Social Services, 30(3), 299-313.

*Donat, M., Willisch, A., & Wolgast, A. (2022) Cyber-Bullying among University Students: concurrent relations to belief in a just world and to empathy. Current Psychology,https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03239-z

*Einarsen, S., Hoel, H., Zapf, D., & Cooper, C. (eds) (2020). Bullying and Harassment in the Workplace: developments in theory, research and practice. Boca Raton, FL, CRC Press.

*Faucher, C., Cassidy, W., & Jackson, M. (2019). Power in the Tower: the gendered nature of cyberbullying among students and faculty at Canadian universities. pp. 66-79 in Cassidy, W, Faucher, C, and Jackson, M (eds) Cyberbullying at University in International Contexts. New York, Routledge.

*Feijo, F., Gräf, D., Pearce, N., & Fass, A. (2019). Risk Factors for Workplace Bullying: a systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16, 1945.

*Fratzl, J., & McKay, R. (2013). Professional Staff in Academia: academic culture and the role of aggression. pp. 60-73 in Lester, J (ed) Workplace Bullying in Higher Education. New York, Routledge.

*Gaffney, H., Ttofi, M., & Farrington, D. (2019). Evaluating the effectiveness of school-bullying prevention programs: an updated meta-analytical review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 45, 111-133.

*Giovaziolas, T., & Malikiosi-Loizos, M. (2016). Bullying at Greek Universities. pp. 110-126 in Cowie, H, and Myers, C-A (eds) Bullying Among University Students: cross-national perspectives. Abingdon, Routledge.

*Gómez-Galán, J., Lázaro-Pérez, C., & Martínez-López, J. (2021). Trajectories of Victimization and Bullying at University: prevention for a healthy and sustainable educational environment. Sustainability, 13, 3426.

Grant, B. (2008). Agonistic Struggle: Master-slave dialogues in humanities supervision. Arts and Humanities in Higher Education, 7(1), 9–27.

*Harrison, E., Fox, C., & Hulme, J. (2020). Student anti-bullying and harassment policies at UK universities. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 42(5), 547-562.

*Harrison, E., Hulme, J., & Fox, C. (2022). A thematic analysis of students’ perceptions and experiences of bullying in UK higher education. Europe’s Journal of Psychology, 18(1), 53-69.

*Heffernan, T., & Bosetti, L. (2021). University bullying and incivility towards faculty deans. International Journal of Leadership in Education,https://doi.org/10.1080/13603124.2020.1850870

*Higgins, P. (2023) “I Don’t Even Recognise Myself Anymore”: an autoethnography of workplace bullying in higher education. Power and Education,https://doi.org/10.1177/17577438231163041

*Hoel, H., Cooper, C., & Faragher, B. (2001). The Experience of Bullying in Great Britain: the impact of organizational status. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 10(4), 443-465.

*Hollis, L. (2015). Bully University? The cost of workplace bullying and employee disengagement in American higher education. Sage Open, April-June, 1–11.

*Hughes, G. (2001). Examples of Good Practice when dealing with Bullying in a Further/Higher Education College. Pastoral Care in Education, 19(3), 10-13.

Jesson, J., Matheson, L., & Lacey, F. (2011). Doing Your Literature Review: Traditional and systematic techniques. Sage.

*Kaur, L, and Kaur, G (2023) Targets’ coping responses to workplace bullying with moderating role of perceived organizational tolerance: a two-phased study of faculty in higher education institutions. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(1083), 19.

*Keashly, L., & Neuman, J. (2010). Faculty experiences with bullying in higher education: causes, consequences and management. Administrative Theory and Praxis, 32(1), 48-70.

*Keashly, L., & Neuman, J. (2013). Bullying in Higher Education: what current research, theorizing and practice tell us. pp. 1-22 in Lester, J (ed) Workplace Bullying in Higher Education. New York, Routledge.

*Keashly, L. (2019). Workplace Bullying, Mobbing and Harassment in Academe: faculty experience. In P Cruz et al (eds) Handbooks of Workplace Bullying, Emotional Abuse and Harassment 4: special topics and particular occupations, professions sectors. Singapore, Springer Nature.

*Koehler, W., & Copp, H. (2021). Observations of LGBT-specific bullying at a state university. Journal of Gay and Lesbian Mental Health, 25, 4, pp. 394-407.

*Kokkinos, C., Baltzidis, E., & Xynogala, D. (2016). Prevalence and personality correlates of facebook bullying among university undergraduates. Computers in Human Behavior, 55, 840-850.

*Lee, J, Choi, H, and deLara, E (2022) Parental care and family support as moderators on overlapping college student bullying and cyberbullying victimization during the Covid-19 pandemic. Journal of Evidence-Based Social Work,https://doi.org/10.1080/26408066.2022.2094744

*Lin, M., Wolke, D., Schneider, S., & Margraf, J. (2020). Bullying history and mental health in university students: the mediator roles of social support, personal resilience and self-efficacy. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10, 960.

*Lund, E., & Ross, S. (2017). Bullying perpetration, victimization and demographic differences in college students: a review of the literature. Trauma, Violence and Abuse, 18(3), 348-360.

*Malik, N., & Björkqvist, K. (2019). Workplace bullying and occupational stress among university teachers: mediating and moderating factors. Europe’s Journal of Psychology, 15(2), 240-259.

*Manrique, M., Allwood, M., Pugach, C., Amoh, N., & Cerbone, C. (2020). Time and support do not heal all wounds: mental health correlates of past bullying among college students. Journal of American College Health, 68, 3, pp. 227-235.

*Meriläinen, M., Sinkkonen, H-M., Puhakka, H., & Käyhkö, K. (2016). Bullying and inappropriate behaviour among faculty personnel. Policy Futures in Education, 14(6), 617-634.

*Moyano, N., & Sanchez-Fuentes, M. (2020). Homophobic bullying at schools: a systematic review of research, prevalence, school-related predictors and consequences. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 53, 101441.

*Nelson, E., & Lambert, R. (2001). Sticks, stones and semantics: the ivory tower bully’s vocabulary of motives. Qualitative Sociology, 24(1), 83-106.

*Nielson, M., & Einarsen, S. (2018). What We Know, What We Do Not Know, and What we Should and Could Have Known about Workplace Bullying: an overview of the literature and agenda for future research. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 42, 71-83.

*Oksanen, A., Celuch, M., Latikka, R., Oksa, R., & Savela, N. (2022). Hate and harassment in academia: the rising concern of the online environment. Higher Education, 84, 541-567.

*Pescitelli, A. (2019). MYSPACE or Yours? An exploratory study of homophobic and transphobic cyberbullying of post-secondary students. pp. 52-65 in Cassidy, W, Faucher, C, and Jackson, M (eds) Cyberbullying at University in International Contexts. New York, Routledge.

*Pörhölä, M., Cvancara, K., Kaal, E., Kunttu, K., Tampere, K., & Torres, M. (2020). Bullying in University between Peers and by Personnel: cultural variation in prevalence, forms and gender differences in four countries. Social Psychology of Education, 23, 143-169.

*Pörhölä, M. (2016). Do the Roles of Bully and Victim remain stable from School to University? pp. 35-47 in Cowie, H, and Myers, C-A (eds) Bullying Among University Students: cross-national perspectives. Abingdon, Routledge.

*Rivers, I. (2016). Homophobic and Transphobic Bullying in Universities. pp. 48-60 in Cowie, H, and Myers, C-A (eds) Bullying Among University Students: cross-national perspectives. Abingdon, Routledge.

*Sallee, M., & Diaz, C. (2013). Sexual harassment, racist jokes and homophobic slurs: when bullies target identity groups. pp. 41-59 in Lester, J (ed) Workplace Bullying in Higher Education. New York, Routledge.

*Schenk, A., & Fremouw, W. (2012). Prevalence, psychological impact and coping of cyberbully victims among college students. Journal of School Violence, 11(1), 21-37.

*Seabrook, M. (2004). Intimidation in Medical Education: students’ and teachers’ perspectives. Studies in Higher Education, 29(1), 59-74.

*Sheridan, J., Dimond, R., Klumpyan, T., Daniels, H., Bernard-Donals, M., Kutz, R., & Wendt, A. (2023). Eliminating bullying in the university: the university of wisconsin-madison’s hostile and intimidating behavior policy. pp. 235-258 in C Striebing, J Muller and M Schraudner (eds) Diversity and Discrimination in Research Organizations. Bingley, Emerald.

*Simmons, J., Bauman, S., & Ives, J. (2016). Cyber-aggression among members of college fraternities and sororities in the United States. pp. 93-109 in Cowie, H, and Myers, C-A (eds) Bullying Among University Students: cross-national perspectives. Abingdon, Routledge.

*Simpson, R., & Cohen, C. (2004) Dangerous Work: the gendered nature of bullying in the context of higher education. Gender, Work and Organization, 11(2), 163-186.

*Sinha, A., & Bondestam, F. (2022). Moving beyond bureaucratic grey zones: managing sexual harassment in Indian higher education. Higher Education, (84), 469-485.

*Smith, F., & Coel, C. (2018). Workplace bullying policies, higher education and the first amendment: building bridges not walls. First Amendment Studies, 52(1-2), 96-111.

*Spanou, K., Bekiari, A., & Theocharis, D. (2020). Bullying and machiavellianism in university through social network analysis. Revista Internacional de Sociología, 78, 1, e151.

*Su, P-Y., Wang, G-F., Xie, G-D., Chen, L-R., Chen, S-S., & He, Y. (2022). Life Course Prevalence of Bullying among University Students in Mainland China: a multi-university study. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37(7–8), NP5830–5840.

*Thomas, M. (2005). Bullying among Support Staff in a Higher Education Institution. Health Education, 105(4), 273-288.

Tight, M. (2021). Syntheses of Higher Education Research: What we know. Bloomsbury.

Tight, M. (2022). Is Peer Review Fit for Purpose? In E. Forsberg, L. Geschwind, S. Levander, & W. Wermke (Eds.), Peer Review in an Era of Academic Evaluative Culture (pp. 223–241). Palgrave Macmillan.

Torgerson, C. (2003). Systematic Reviews. Continuum.

*Twale, D. (2018). Understanding and preventing faculty-on-faculty bullying: a psycho-social-organizational approach. New York, Routledge.

*Vaill, Z., Campbell, M., & Whiteford, C. (2020). Analysing the quality of australian universities’ student anti-bullying policies. Higher Education Research and Development, 39(6), 1262-1275.

*Vaill, Z., Campbell, M., & Whiteford, C. (2023). University students’ knowledge and views on their institution’s anti-bullying policy. Higher Education Policy, 36(1), 1-19.

*Young-Jones, A., Fursa, S., Byrket, J., & Sly, J. (2015). Bullying affects more than feelings: the long-term implications of victimization on academic motivation in higher education. Social Psychology of Education, 18, 185-200.

*Yubero, S., Heras, M. de las., Navarro, R., & Larrañaga, E. (2023). Relations among chronic bullying victimization, subjective well-being and resilience in university students: a preliminary study. Current Psychology, 42(2), 855-866.

*Zabrodzka, K., Linnell, S., Laws, C., & Davies, B. (2011). Bullying as intra-active process in neoliberal universities. Qualitative Inquiry, 17(8), 709-719.

*Zawadzki, M., & Jensen, T. (2020). Bullying and the neoliberal university: a co-authored autoethnography. Management Learning, 51(4), 398-413.

*Zhao, J., Lu, X-H., Liu, Y., Wang, N., Chen, D-Y., Lin, I-A., Li, X-H., Zhou, F-C., & Wang, C-Y. (2022). The unique contribution of past bullying experiences to the presence of psychosis-like experiences in university students. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13(839630), 10.

*Zych, I., Viejo, C., Vila, E., & Farrington, D. (2021). School bullying and dating violence in adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Trauma, Violence and Abuse, 22(2), 397-412.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tight, M. Bullying in higher education: an endemic problem?. Tert Educ Manag 29, 123–137 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11233-023-09124-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11233-023-09124-z