Abstract

This paper analyses a novel and increasingly prevalent category of epistemic behaviour: doombehaviour, constituted by the popular phenomena of doomscrolling and doomsurfing, as well as doomchecking, which is introduced in this paper. Doombehaviour, referring to the frequent or immersive online consumption of negatively valenced news, became ubiquitous during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic. As this behaviour has since then been found to negatively impact mood and mental health, advice has been to minimise doombehaviour or even limit news consumption altogether. Yet, as I argue, this assessment overlooks the importance of the epistemic motivation instantiating the behaviour. By presenting an analysis of doomscrolling, doomsurfing, and doomchecking within the context of our socio-technical environment, arguing for the distinct instrumental epistemic values of these categories of doombehaviour, this paper provides more nuanced advice for individuals seeking to balance the potential epistemic benefits and prudential costs of this behaviour. Epistemically motivated individuals should refrain from doomscrolling due to the risk of consuming sophisticated misinformation. However, within the parameters presented in this paper, the epistemic goods obtained through doomchecking and doomsurfing may justify the prudential costs for individuals motivated to acquire knowledge of, or be informed about, current events. This discussion opens the door to further explorations of these increasingly prevalent and potentially harmful epistemic behaviours that have, so far, been ignored by the discipline.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 The introduction of doombehaviour

At the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, ‘doomscrolling’Footnote 1 and ‘doomsurfing’ became frequently employed terms to describe the increasingly prevalent practice of frequent or immersive online information acquisition related to distressing current events, often inducing a sense of doom. The uncertainty and insecurity characterising this time led to a spike of online news consumption, as people looked for updates on lockdown regulations, the spread of the virus, and its possible cause, on top of acquiring previously unfamiliar concepts such as ‘r-value’ and ‘mRNA vaccine’ (Anand et al., 2022; Price et al., 2022). Over time, other distressing topics, such as police brutality directed at people of colour and extreme weather events related to the climate crisis, became part of this continual consumption of negative news. This increase in news consumption mainly occurred on traditional and social media platforms, which offer a seemingly never-ending stream of distressing information (Price et al., 2022).

As this behaviour became increasingly prevalent and normalised, its negative effects on the mood and mental health of those engaging in the practice became evident (Mannell & Meese, 2022; Price et al., 2022; Ytre-Arne & Moe, 2021). Multiple media outlets and even government entities have thereby advised to limit doomscrolling and doomsurfing (Garcia-Navarro, 2020; Mannell & Meese, 2022; Roose, 2020), problematic news consumption (McLaughlin et al., 2022), or reduce news consumption in general (Head to Health, 2020; World Health Organisation, 2020; Mannell & Meese, 2022). While the relevant behaviour has thereby amassed academic and media attention, the topic has not seen any philosophical engagement. This is especially surprising as doomsurfing and doomscrolling refer to ubiquitous and potentially harmful online epistemic behaviours, making it a fruitful topic for philosophers of well-being, epistemologists, and philosophers of technology. Moreover, as I aim to show in this paper, a philosophical analysis of this behaviour allows us to provide more fine-grained advice than limiting news consumption altogether, in addition to incorporating the potential epistemic value of the behaviour and the potential goals of those who enact it, rather than merely focussing on its prudential costs.Footnote 2

In the following section I discuss what I call doombehaviour, i.e., the frequent or long-lasting online consumption of information on current events that the agent finds distressing and that generally induce a sense of doom. This sense of doom entails a sense or expectation that further updates on the topic will be similarly distressing, or that similar or similarly distressing events will occur. To analyse this behaviour and its effects, I employ the existent literature on its constitutive elements of doomscrolling and doomsurfing, as well as analyses of problematic news consumption more generally. The words ‘doomscrolling’ and ‘doomsurfing’ have been described as distinct in terms of platform, physical activity, and level of passivity (e.g. Anand et al., 2022; Ytre-Arne & Moe, 2021). I argue that if we accept these differences, the respective concepts refer to distinct epistemic behaviours that differ in epistemic value. Doomscrolling, as I discuss in Sect. 2.1, refers to passively scrolling on a social media platform, attending to negatively valenced information. Doomsurfing, discussed in Sect. 2.2, rather entails goal-directed deep-dives into negatively valenced topics. In Sect. 2.3 I introduce the term doomchecking, referring to frequently opening trusted news sources to check specific facts—another practice that became increasingly ubiquitous since the COVID-19 pandemic. Lastly, in Sect. “2.4” I argue that these forms of doombehaviour are ubiquitous due to two elements. First, our current sociotechnical environment does not merely provide the necessary platforms for doombehaviour to occur; it actively promotes its enactment. Second, as doombehaviour is partly constituted by an affective feedback loop, where negatively valenced affective states direct attention to distressing information, which in turn results in further negative affect, doomscrolling, doomchecking, and doomsurfing can be self-sustaining practices, or can lead one to act on a different category of doombehaviour.

From Sect. 3, doomscrolling, doomsurfing, and doomchecking are analysed in terms of their relation to acquiring epistemic goods such as true belief, knowledge, and understanding, to assess whether these behaviours are advisable from an epistemic perspective. While I argue that all doombehaviour is directed towards the acquisition of non-trivial beliefs, I note that doomscrolling is unlikely to lead to knowledge as its platform is notorious for presenting sophisticated disinformation and misinformation. If an agent aims to acquire knowledge on current events, then, doomscrolling does not aid her in reaching this goal. Doomchecking and doomsurfing, on the other hand, appear to be epistemically worthwhile given their respective relation to knowledge and understanding acquisition.

Section 4 argues that if we accept the distinction between doomscrolling, doomchecking, and doomsurfing presented in this paper, we need not advise against doombehaviour, let alone news-consumption, as a whole. While the limited epistemic value of doomscrolling leads the practice to be in conflict with epistemic (and prudential) concerns, the epistemic value of doomsurfing and doomchecking is dependent on two elements: the agent’s ability to discern trustworthy news outlets and their pre-disposition to experience anxious or depressive moods, the latter element having the potential to undermine their epistemic goals. As such, where an agent values being informed or to acquire knowledge more generally, they can choose to engage in doomsurfing and doomchecking, despite these practices resulting in the negatively valenced sense of doom.

2 The categories of doombehaviour

This section presents an interdisciplinary analysis of the existent concepts of doomscrolling and doomsurfing. It then introduces doomchecking as a category of doombehaviour which, while previously categorised as doomsurfing, differs from this practice in significant ways. Finally, I discuss the causal interactions between these three categories of doombehaviour, as well as how our current epistemic environment gives rise to doombehaviour as a whole.

2.1 Doomscrolling

The term ‘doomscrolling’ was already in use before the pandemic, referring to the immersive practice of scrolling through social media, attending to information that caused a sense of impending doom (Garcia-Navarro, 2020). Subsequent accounts further compare doomscrolling to passive social-media engagement: users scrolling through their feed, absorbing information without sharing, liking, or commenting on this information and without leaving the platform, where this activity is reinforced by the design of the platform rather than by the user’s volition (e.g., Sharma et al., 2022). Akin to other passive social media engagement, doomscrolling can start with a goal-directed action, such as opening the app to see whether a potentially important event or topic is being discussed. It can thereby also be endorsed by the agent: if she aims to acquire knowledge on timely topics, that may generally be distressing, discussed by people or organisations that she follows, she may consider doomscrolling a fruitful method to accomplish this goal. But the design of these platforms, which includes notifications, a tailored feed, and (almost) always presenting the user with new information, also enforces habitually opening the relevant platform without conscious motivation to do so. Doomscrollers, then, often automatically open a news-heavy social media app or website and, due to the immersive quality of the practice, tend to stay on this platform for a long time, often without intending to do so (Sharma et al., 2022). However, doomscrolling is distinct from other passive social media use; automatically opening or scrolling through social media feeds need not be related to consuming negatively valenced information on current events, where this is a requirement for doomscrolling.

The doomscroller’s attention is drawn to negatively valenced or shocking information, which is taken in without active engagement (Sharma et al., 2022). While social media users’ attention tends to be drawn to negatively valenced information in general, the initial uncertainty caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as other negatively valenced affective states caused by consuming distressing news (through doomscrolling or other methods), intensifies this effect (Price et al., 2022). Moreover, the negative affective state caused by doomscrolling can, in turn, motivate further doomscrolling as the agent attempts to ‘up-regulate their mood’ through further engagement with the social media platform (Anand et al., 2022, p. 2). Yet even without such intended up-regulation, the platforms employed for doomscrolling are designed to grab and keep the agent’s attention for prolonged periods of time, making instances of doomscrolling last longer than initially intended (e.g., Williams, 2018). This makes doomscrolling a vicious cycle of negative information gathering, which helps explain the longevity and prevalence of doomscrolling sessions. It also illustrates the low level of agency that tends to characterise the practice which, as I argue in Sect. 4, is relevant for its minimal epistemic value.

2.2 Doomsurfing

Unlike ‘doomscrolling’, ‘doomsurfing’ was specifically coined to describe the epistemic behaviour prevalent at the start of the pandemic, where a sense of uncertainty led many to surf the web in an effort to understand what was happening and why. Similar to doomscrolling, then, doomsurfing is often motivated by negative affect which, due to the content consumed, is usually only amplified by the practice.Footnote 3 Unlike doomscrolling, however, doomsurfing is described as goal-oriented, with agents seeking information on a particular topic to try and make sense of it (Anand et al., 2022).

Rather than being limited to newly uncovered information, doomsurfing can involve learning about the history or context of a distressing topic, such as chemical weapons, racism, or pandemics, to understand the relevant timely subject or development. Likewise, it can entail attempts to understand complex scientific terms, exemplified by attempts to understand the definition and importance of COVID-19’s ‘r-value’—a term that was relatively unknown to laypeople before the pandemic yet now seems in common use.

The topics one doomsurfs about may include, e.g., Russian invasion of Ukraine, the pandemic, and climate change. As these topics are complex and continually in flux, one always seems to be able to acquire more relevant information. This, in part, explains the immersive characteristic of doomsurfing: imagine an agent who may simply want to understand why energy prices are increasing. This topic is complex, with multiple causes that are widely reported on, most of which being distressing and inviting further research. Hours later, then, this agent can still be reading about the possibility of China aiding Russia in its invasion of Ukraine, or the record profits shareholders of major energy companies received. This quality has caused doomsurfing to be linked to another popular concept describing similar online behaviour: falling into a rabbit hole (e.g., Gilbertson, 2020), which also refers to long-lasting, immersive, and difficult to stop deep-dives into a particular topic (Cambridge University Press, n.d.). However, while an agent can fall into a rabbit hole because the relevant topic makes them especially excited, doomsurfing is restricted to (topics related to) current events that the agent experiences as distressing. Doomsurfing, then, is enacted to acquire some understanding or broaden one’s knowledge of the relevant and distressing topic or event, leading to prolonged episodes of immersed online research.

2.3 Doomchecking

At the start of the pandemic, many started to frequently check for updates on the spread of COVID-19 and lockdown regulations. This was soon followed by tracking the death toll of COVID-19, extreme weather events (Anand et al., 2022), and more recently, developments of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. I categorise this frequent checking for updates on specific facts related to timely topics as doomchecking. In what follows I discuss three differences between doomchecking and other doombehaviour: their temporal extension, immersive quality, and epistemic parameters.

First, doomchecking refers to short-lived instances of information acquisition, in contrast to the prolonged sessions of social media engagement or the time-consuming deep-dives characterising doomscrolling and doomsurfing respectively. It would, after all, be odd to identify reading a single social media post as doomscrolling; there would be very little scrolling involved. Likewise, doomsurfing implies surfing across pages or platforms to consume the relevant distressing content. Doomchecking, on the other hand, merely entails checking some specific piece of information on one particular platform which has previously been employed to check this piece of information. As such, compared to doomscrolling and doomsurfing, an instance of doomchecking is relatively brief.

A prolonged session of doomchecking would rather refer to the enaction of multiple instances of doomchecking.Footnote 4 For example, checking the current r-value of COVID-19 can be followed by checking whether Russia has employed chemical weapons, which may in turn be followed by checking whether the drought in Italy has subsided. These examples describe three distinct epistemic actions related to three distinct topics, i.e., three instances of doomchecking. Doomchecking, then, is less temporally extended than doomscrolling and doomsurfing.

Second, this difference qua temporal extension is, in part, due to doomscrolling’s and doomsurfing’s immersive phenomenological quality. It is because of this quality that agents lose track of time while engaging in these behaviours, which thereby allows them to continue for longer than they realise or intend (Sharma et al., 2022). As doomchecking refers to short-lived individual instances of epistemic action, this immersive quality is unlikely to occur.

Third, doomchecking has fixed epistemic parameters, i.e., a particular fact or group of facts which has (recently) been checked before. Whether this is applied to checking COVID-19’s r-value, its total fatalities, or updated developments of a distressing event, the doomchecker specifically aims to acquire a particular belief or group of beliefs and once this is acquired, the act of doomchecking is completed.Footnote 5 In contrast, doomscrollers may expect to acquire beliefs on a broad array of negatively valenced topics as they scroll through their timeline. Moreover, while doomsurfers focus on a particular topic, their intention is to acquire information that will contextualise, explain, or help them make predictions about the relevant subject. In other words, doomscrollers and doomsurfers accumulate a broad array of beliefs during their long-lasting immersive activity which they need not have expected to acquire.

One similarity between doomscrolling and doomchecking entails the potential automaticity of this epistemic behaviour, as checking particular facts may become habitual over time. Similar to doomscrollers automatically opening their social media platform of choice, then, doomcheckers may automatically open websites containing updated information on the facts they tend to doomcheck. Whether this entails liveblogs on the progression of the Russian invasion of Ukraine or a search engine providing them with the updated death toll of COVID-19, doomchecking is enacted to acquire particular beliefs or groups of beliefs, as the act is concluded once this specific information is acquired.Footnote 6 Similarly, while I automatically turn on the coffee machine in the morning, this is nevertheless goal-directed behaviour, i.e., to make coffee.

2.4 Doombehaviour

With a description of these three categories of doombehaviour at hand, I now note that doombehaviour is a pressing topic to discuss given its ability to blossom in our current sociotechnical environment. Moreover, while the three forms of doombehaviour outlined in the previous section are distinct, acting on one category can result in acting on other categories as well, further increasing the prevalence of doombehaviour as a whole. Both elements are respectively discussed in this section.

Doombehaviour is supported and motivated by an abundance of accessible distressing information, which is provided through an interaction of two elements. First, as doombehaviour is directed towards distressing information on current events or topics, the prevalence of distressing events or developments taking place presents the agent with a constant stream of topics that can serve as the objects of one’s doombehaviour. This can be illustrated by the word permacrisis, referring to ‘an extended period of instability and insecurity’ (Collins, 2022), being the Collins Dictionary’s word of the year 2022. In other words, the wars, economic distress, global issues, and political upheaval constituting 2022’s permacrisis present an agent with objects for doombehaviour, as well as causing a sense of uncertainty, distress, or anxiety that motivates such doombehaviour.Footnote 7 Second, our current socio-technical environment allows us to acquire information from all over the world at any time of day, thereby providing easily accessible platforms for doombehaviour to occur. Moreover, these platforms are often designed to grab and keep our attention, whereby the long-lasting epistemic activities of doomscrolling and doomsurfing are enforced by the relevant platform (e.g., Williams, 2018).

All three doombehaviours presented in this paper are affected by this permacrisis and the immediate access to relevant information that is often presented on attention-grabbing platforms. First, social media platforms are specifically designed to grab and keep a user’s attention, on top of habituating engagement with such platforms. Due to the permacrisis, this social media engagement can quickly turn into doomscrolling given the abundance of posts and headlines referring to novel distressing topics or developments on said platforms. Second, given the number of topics causing a sense of uncertainty, anxiety, or distress that constitute the permacrisis, the objects for doomsurfing are abundant. Moreover, due to the available technology, information on such topics is immediately accessible on websites which frequently present the user with further information to consume, either on the topic at hand or another distressing, attention-grabbing subject. Third, smartphones allow one to quickly doomcheck at any time and during any situation. Moreover, the permacrisis motivates doomchecking with regards to particular topics as these objects of doomchecking are everchanging—a relevant aspect for the epistemic value of the practice that will be discussed in Sect. 3.3—on top of motivating a more general form of doomchecking, as I shall discuss briefly.

Living in a permacrisis entails that there are various specific distressing developments or events that one can check up on at any time. However, the insecurity and uncertainty characterising such a crisis may also lead one to check whether any novel noteworthy events have occurred. For instance, the climate crisis leads to frequent weather-related disasters like hurricanes and floods. As such, one may check a news app to see whether any new weather disasters have occurred. Likewise, political upheaval may cause important government plans or sanctions to change in quick succession. As such, one may be motivated to frequently check a particular news app or website to check whether any novel distressing event has occurred, rather than, or on top of, checking for developments on known distressing events or topics.

Note that this general variant of doomchecking still merely entails an act to acquire a specific group of beliefs, i.e., whether a novel distressing event or development has occurred and what this event or development roughly entails. Coming to know the fact in question may motivate doomsurfing, aiming to acquire more information on the topic, or doomscrolling as a way to either up-regulate one’s mood or to see how this and similarly distressing topics are represented on social media. Yet note that doomchecking can also induce curiosity or interest, motivating further news consumption without the immersive and time-consuming qualities that characterise doomsurfing and doomscrolling.

The above illustrates the way in which one category of doombehaviour can motivate enacting another. Such causal interactions link all categories of doombehaviour. After all, as an agent doomscrolls she can come across an especially tantalising or distressing topic. This may motivate her to click on the relevant articles to get a better understanding of this topic, falling into a rabbit hole of distressing content. In other words, doomscrolling may motivate, or turn into, doomsurfing. Additionally, akin to doomchecking, doomsurfing can lead to doomscrolling. After all, an agent who recently doomsurfed may be incentivised to check social media to see how the event or topic is interpreted by others or, due to the distressing nature of the content consumed, to up-regulate her mood. Even when the goal has been reached (or when it has become clear that the goal cannot be accomplished through opening social media), the mentioned qualities of social media platforms can keep the agent scrolling through her feed while being primed to attend to distressing content.

Moreover, an understanding of the pressing quality of certain current events acquired through doomsurfing, or noticing others frequently sharing their views on these topics while doomscrolling, can lead to doomchecking as one aims to be up to date regarding these events in a way that mirrors their pressing nature or the knowledge possessed by one’s social circle. Finally, as all doombehaviour tends to induce a sense of doom in the agent, any form of doombehaviour can motivate another: the expectation that further distressing updates will be provided, or that other, similarly distressing, events may occur, can induce the fear that these instances may have happened and have been reported on already, motivating both doomchecking and doomscrolling. It also motivates doomsufing, where one responds to this sense of doom by looking for more information on how bad the event really was and the likelihood of it continuing or reoccurring. While these behaviours are thereby causally linked, in what follows I argue that they are distinct in epistemic value when conceptualised as methods of inquiry, making the case for the practical use of the distinct concepts as discussed.

3 The epistemic value of doombehaviour

As I discuss in Sect. 4, doombehaviour often comes with prudential costs, including a higher probability of experiencing depressive moods or anxiety. Even when agents are unaware of this risk, that doombehaviour induces prolonged negatively valenced affective states should be quickly clear to them as a consequence of consuming content they deem distressing. Nevertheless, many engage in instances of doombehaviour as they, e.g., aim to be informed on current events, are invested in particular topics (e.g., trans rights or the climate crisis), or are curious about the development of a distressing incident. That is, doombehaviour tends to be epistemically motivated.Footnote 8

In this section I therefore analyse the relation between doomscrolling, doomsurfing, and doomchecking, and what is arguably the fundamental epistemic value: truth (e.g., Alston, 2005, p. 29; BonJour, 1985, p. 7; Pritchard, 2014; Sosa, 2007). If we accept truth as the fundamental epistemic value, we can accept a derived fundamental epistemic norm, which Brogaard (2014, p. 16) names the truth norm, stating that one ought to believe p iff p is true.Footnote 9 This norm then forms the basis of further epistemic norms, such as ‘believe true propositions’, ‘do not believe falsehoods’, and ‘aim to accumulate knowledge’.Footnote 10

Additionally, I respectively assess the epistemic goods doomscrolling, doomsurfing, and doomchecking stand in relation to, where the epistemic value of these goods informs the instrumental epistemic value of these behaviours. To do so, I first employ the intuition that knowledge is more valuable than true belief (Plato, Meno; Pritchard, 2007; Zagzebski, 2003). What distinguishes knowledge from true belief, on most contemporary accounts, is that the agent is justified in believing the relevant true proposition, in addition to avoiding Gettier cases. The difference between true belief, true and justified belief, and knowledge can be illustrated through the true belief p that there is a blue car in front of one’s front door. When p is merely a true belief, the agent believes p without justification, or through an unreliable justification such as receiving testimony from a known liar or wishful thinking (e.g., she likes blue cars and believes that whatever she likes will come to her). This agent happens to be right in believing that p, but she lacks the justification necessary for knowing that p. Second, when the agent owns a blue car and parked it in front of her house, she is justified in believing p. However, if her car was just stolen and the parking spot is now used by another blue car, she has a justified and true belief that p, but she still lacks knowledge.

While it is outside of the scope of this paper to argue for one particular account of knowledge that both avoids Gettier cases and is able to account for the intuition that knowledge is more valuable than true belief, others have argued for such accounts. For example, knowledge can be considered more valuable than true belief because acquiring knowledge is an achievement that has to be attributable to the agent rather than luck (Brogaard & Smith, 2005; Pritchard, 2009), or because knowledge is acquired through a reliable mechanism, where this reliable mechanism justifies the agent to believe p and her belief is true because it was acquired through this reliable mechanism (e.g., Brogaard 2006; Riggs, 2002; Sosa, 2015). So in the Gettier case, while the agent’s generally reliable faculty of memorisation justifies her belief that there is a blue car parked outside her door, as she remembers parking it there, her belief is not true due to this memorisation capacity as there is now a different blue car taking up this spot. On both accounts, the fact that the agent acquired a true rather than false or unjustified belief is attributable to the agent rather than luck. This will be discussed further in Sect. 3.1.

Second, I employ the intuition that understanding is more valuable than propositional knowledge (e.g., Grimm, 2010; Kvanvig, 2003; Pritchard, 2009; Zagzebski, 1996, 2001). The difference between knowledge and understanding can be illustrated by Pritchard’s (2009) example of understanding the cause of a fire. Imagine an epistemic agent who witnesses his home being destroyed by a fire and is informed by a firefighter that the fire was caused by faulty wiring. If this agent researches how faulty wiring can lead to fires, or already understands the dangers of faulty wiring, he understands why his house burnt down. If he subsequently tells his young son, who knows nothing about the topic, that the fire was caused by faulty wiring, the son now knows why the house burnt down, but does not understand why it did. Understanding can be considered more valuable as it, e.g., better reflects the world (Grimm, 2010, 2011; Kranvig 2003), is more of an achievement to acquire than propositional knowledge (Pritchard, 2010; Zagzebski, 2001), or is better suited to avoid scepticism (Zagzebski, 2001, p. 245). For those who argue that all understanding is reducible to propositional knowledge (e.g., Stanley & Willlamson, 2001), understanding why the house burned down may still be more valuable than knowing why the house burned down when the former entails that the agent possesses more knowledge. Namely, knowledge that connects the pieces of knowledge on faulty wiring to those related to how fires start.

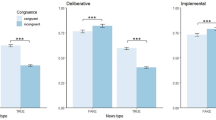

In what follows I argue that, if we accept this intuitive epistemic value distribution, we would find a similar distribution in doomscrolling, doomsurfing, and doomchecking for agents who aim to employ reliable sources in order to be informed on current events. As I argue in Sect. 3.1, doomscrolling allows agents to acquire beliefs that may be true, yet due to the epistemically hostile environment in which they are acquired, these beliefs would not amount to knowledge. In Sect. 3.2, I argue that doomsurfing allows agents to acquire an understanding of contemporary issues or current events. Finally, in Sect. 3.3 I argue that doomchecking allows agents to acquire propositional knowledge, yet it does not lead to the acquisition of understanding. If we accept that these behaviours are causally connected to epistemic goods that differ in epistemic value, this ought to be taken into account when assessing their advisability in the context of their potential prudential costs, as discussed in Sect. 4.Footnote 11

3.1 The epistemic value of doomscrolling

When doomscrolling, users scroll through their feed, automatically attending to the negatively valenced information and often sensationalised headlines in the seemingly unending stream of posts the platform presents them with. The previously discussed passive quality of this behaviour is especially relevant in terms of the doomscrollers’ reported habitual, unreflective, and unintended social media use (Sharma et al., 2022). Recall that, while doomscrollers may have a(n epistemic) goal in mind when opening the relevant platform, this need not be the case, and the behaviour tends to continue when the goal has been satisfied or forgotten. Compared to doomsurfing and doomchecking, then, doomscrolling refers to a relatively passive form of information acquisition.

This would normally not be a problem: much of our knowledge is somewhat passively acquired (e.g., Baehr, 2011; Sosa, 2017). For example, imagine someone working in her office when the light turns off. Her subsequent belief that the light is off is automatically acquired, yet she nevertheless knows that the light is off. However, if we imagine that she shares her office with a prankster who is known for placing cardboard boxes over lightbulbs, her automatic, intuitive belief may be false. When she is aware of this prankster, then, she only knows that the light is off after ruling out the possibility that she is being tricked.

Something similar can be said of the doomscroller who gets her news from social media platforms, i.e., platforms notorious for spreading sophisticated disinformation (Bradshaw & Howard, 2019; Dawson & Innes, 2019; Johnson and St. John, 2020; Morgan, 2018). Doomscrollers are therefore likely to be confronted with content specifically designed to trick users into believing misinformation.Footnote 12 As such, akin to the office worker, users may be tricked into believing falsehoods. For the doomscroller faced with potentially sophisticated disinformation or misinformation, however, checking the veridicality of the acquired belief is more difficult and effortful than for the office worker checking whether the lightbulb is covered by a box. Moreover, due to doomscrolling’s posited passivity, doomscrollers are unlikely to start this difficult or effortful process. However, if they do start this process by, e.g., employing other sources, reading the relevant articles and assessing the trustworthiness of these sources, they can no longer be said to be doomscrolling, as this behaviour is closer to doomsurfing or just plain research. When the agent acquires true beliefs through doomscrolling without checking that the information comes from a trustworthy source, then, she is not justified in holding these beliefs, making them fall short of knowledge.

Even when merely attending to posts by those she deems epistemically trustworthy, doomscrolling agents may nevertheless be tricked. For example, doomscrollers may mistake ‘retweets’, ‘shares’, or ‘likes’ from trusted users for endorsements of the liked or shared content, thereby assuming the content to be true and justified, without this being intended by the trusted user (Marsili, 2021; McDonald 2021). Moreover, the doomscroller is unlikely to know how vigilant the users she follows are in verifying their sources. This is especially concerning as users are more likely to believe and share information posted by trusted friends and public figures than the original source of the information (Sterrett et al., 2019; Tandoc, 2019).

Moreover, while one may consider (certain) newspapers as sufficiently trustworthy, if one only reads the headlines of the relevant articles, i.e., scrolling through them rather than clicking on the article itself, one can still be misled through the oversimplification or sensationalisation of the title used to attract engagement. For example, while the headline ‘25 dead in hurricane disaster’ in a trusted newspaper may induce the belief that the destructive force of a hurricane killed 25 people, reading the accompanying article would let the agent know that only ten people died at the time of the hurricane, the rest dying due to a lack of assigned relief funds.

So, when the user does not consider the social media platform to be epistemically hostile as she, e.g., has curated her account by only following people she trusts, including reputable newspapers, then this epistemic environment also connects doomscrolling to an influential Gettier case. The fake barn country case, first introduced by Goldman (1976), asks us to imagine someone driving through farmlands, perceiving various barns down the road. What this agent does not know, however, is that some of these barns are merely facades. So, when this agent forms the belief that she is driving past a barn, even when this belief is true and justified (as her perception of a barn justifies her belief that there is a barn), her belief does not amount to knowledge; she merely got lucky in forming her belief while driving past a real barn. Similarly, the doomscroller may acquire a belief that is true and justified, e.g., by reading a post of a trusted user containing true information on current events. Yet, given possibility of being tricked, or the trusted user having been tricked, this belief would not amount to knowledge.

Note that this conclusion is reached through the definition of doomscrolling supported in the, admittedly sparse, research that has so far been conducted on the topic. Given the abundance of sophisticated misinformation, the doomscroller ought to become active in her research and leave the relevant social media platform in order to check whether believing the presented information is justified, perhaps inducing the idea that this research can be constitutive of doomscrolling. Yet to argue that doomscrolling can entail moving across platforms to be sufficiently informed to accept the information as veridical, the distinction between doomscrolling and doomsurfing posited in the current literature would have to be abandoned. If we were to reject this distinction, we are back where we started: with the advice that doombehaviour ought to be minimised as a whole, despite this behaviour coming in demarcated forms with, as I argue, distinct epistemic values. Pragmatically, accepting the categorisation presented in this and previous papers allows us to distinguish between epistemically fruitful and degenerative activities, making the foundation for resulting norms or advice related to this behaviour more fine-grained, allowing us to avoid throwing out the baby with the bathwater.

Doomscrolling, then, plausibly leads users to acquire false beliefs, whether this is due to sophisticated disinformation or sensationalised headlines. Moreover, given doomscrolling’s passive nature, users are unlikely to perform the required research to ascertain whether their acquired beliefs are based on false or misleading information. Even when they do perform this research, this research is merely motivated by beliefs acquired through doomscrolling, rather than being constitutive of the doomscrolling itself. As such, doomscrolling is likely to undermine the epistemic norm of avoiding falsehoods. Moreover, even when one acquires true beliefs while doomscrolling, these beliefs would not amount to knowledge as the agent can be unjustified in holding these beliefs or, when acquiring information through otherwise trusted users, due to the Gettier effect. Doomscrolling thereby has little epistemic value.

3.2 The epistemic value of doomsurfing

In contrast to doomscrolling, doomsurfing does not inherently lead to encountering misinformation or Gettier case pitfalls. This is, first, due to the platforms employed. While doomscrolling is restricted to social media, the doomsurfer chooses other platforms that she trusts. This allows the doomsurfer to opt for, e.g., trusted newspapers, online encyclopaedias, or journal articles. Ultimately, the success of doomsurfing in producing knowledge therefore lies in the trustworthiness of the sources chosen by the agent. Note that the trustworthiness of these sources can differ based on the agent’s situation. For example, while agents living in the UK may trust state-funded media to present an accurate portrayal of current events, and are generally justified in their trust, the same cannot be said for agents living in North-Korea.

Second, doomsurfing entails consuming more in-depth information on a distressing topic, in contrast to the doomscroller who tends to scroll through headlines or articles summarised in one tweet or post. As such, the doomsurfer is unlikely to be misled by over-simplified or sensationalised headlines, making her less likely to undermine the epistemic norm of avoiding falsehoods on that basis alone. Moreover, as doomsurfing leads one to research a topic across platforms, rather than merely employing one source, the doomsurfer is less likely to be taken in by the rhetoric or false information promoted by any one particular platform.

Moreover, the longevity of doomsurfing, enforced by its immersive quality as one loses track of time while researching a topic, allows one to acquire more beliefs on this topic than when one stops one’s research once the initial question is answered or article is read. Doomsurfing is thereby likely to lead to more knowledge than one would have acquired when merely reading a physical newspaper or watching the news, simply because there is no natural stopping point and the immersive quality of the behaviour in combination with the design of the relevant platforms leads to more time spent on information acquisition.

Additionally, as the doomsurfer usually aims to make sense of a particular topic or situation, she is likely to acquire understanding as well as propositional knowledge. Imagine a doomsurfer researching the spread of the virus during the first wave of the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic. During this deep-dive, she learns that the disease’s r-value represents the virus’ ability to spread and how this relates to the virus’ own characteristics and the extrinsic measures taken to minimise the spread. This is in contrast to, say, a doomchecker who occasionally checks COVID-19’s current r-value—an abstract number which, when it drops below 0.9, affects government mandated lockdown regulations. The latter agent, similar to the son in Pritchard’s burning house example, merely knows that an r-value of 0.9 will result in decreased lockdown regulations. The doomsurfer, on the other hand, comes to understand that the r-value (the virus’ ability to spread) of 0.9 (meaning that, on average, one infected person will pass the virus on to less than one other person), is linked to decreased regulations.

Recall that in Pritchard’s example, the agent can either research how faulty wiring can cause fires after listening to the firefighter, or he can already have an understanding of faulty wiring and how they relate to fires. Likewise, then, someone who doomchecks the r-value of the virus can already possess an understanding of what this number represents and can therefore understand that an r-value of, e.g., 1.8 does not lead to decreased lockdown regulations. However, note that this entails that she applied her prior understanding; even if she did not learn that the r-value at that time was 1.8, she would have understood what this would mean in terms of the spread of the virus and lockdown regulations. In other words, she already possesses the understanding that allows her to interpret what any r-value represents. In other words, doomsurfing can lead to an understanding of timely topics, which can in turn be applied to inform one’s interpretation of information, including information acquired through doomchecking.

Yet there are still two things to note given this analysis. First, the understanding one acquires through doomsurfing can inform one’s interpretation of information found online, yet this need not make doomscrolling a reliable method of knowledge-acquisition. For example, if an agent doomscrolls through her feed and sees the headline “With Covid cases dwindling, the government encourages the public to Eat Out to Help Out” she may form the belief that the virus’ ability to spread has decreased sufficiently to safely frequent restaurants or cafes. If the agent has the prior understanding just discussed, this (widely considered to be false——see, e.g., Evans, 2023; Fetzer, 2022) belief may lead to an inaccurate understanding of the situation. That is, without checking the r-value upon reading the headline, as well as the reasons behind it dwindling (the prior lockdown) or rising (e.g., opening schools and pubs), the agent may consider herself to understand the headline: that it is safe to eat out as the r-value is below 0.9 (which was not the case during the promotion by the UK government to eat out for half the price) and that other measures are likely to be in place to avoid a sharp rise in the spread of the virus (which was also not the case). In other words, to avoid the acquisition of false beliefs or inaccurate understandings, doomscrolling needs to be supplemented by further research as the agent cannot always rely on her prior understanding to adequately interpret headlines or misinformation.

Second, doomsurfing itself can lead to an inaccurate understanding of the relevant topic or event. Akin to all forms of online inquiry, the sources one employs to acquire the sought-after information may be unreliable. This is enforced by the personalised nature of the platforms the agent may employ, where these platforms tailor the search results they present to the individual user’s search history, as well as the particular wording of the initial inquiry. For example, given one’s wording or search history, researching climate change may result in the suggestions of different sources, including unreliable ones, for different people on platforms such as Google or Youtube (e.g., Alfano et al., 2021; Pariser, 2011). Where the research of one agent may lead them to sources outlining the deadly consequences of man-made climate change, the research of another may lead them to sources claiming that man-made climate change is a hoax. The rabbit holes one falls into due to doomsurfing may thereby lead one to come to an understanding of a complex and important topic, but they may also lead one to consume a lot of information supporting conspiracy theories. As such, unlike merely checking facts online, as discussed in the following section, doomsurfing may lead one to ascertain a wealth of information that changes one’s view on a topic as a whole, which may be for the worse.

Yet note that there is a discussion to be had on whether prolonged exposure to conspiracy theories is sufficient or the main factor for the agent to believe the presented information, or whether accepting the information as true is attributable to other factors. For example, an agent might need to possess intellectual vices such gullibility (Cassam, 2019b) or intellectual arrogance (Vitriol & Marsh, 2018). Other tendencies, such as having a conspiracy mindset, or affective states such as uncertainty (van Prooijen and Jostmann, 2013) can also be relevant. Many psychological and environmental factors, aside from the how convincingly written a conspiracy article is, can play a part in whether the information is accepted, rejected, or even sought out (Douglas et al., 2019). So, while doomsurfing could lead to the acceptance of conspiracy theories, this relation is not robust. As such, given their opportunity of choosing trustworthy platforms, tendency to move across platforms or sources, and consumption of more (detailed) information, doomsurfers are more likely to acquire an accurate understanding of the topic at hand than those who do not engage in immersive deep-dives.

3.3 The epistemic value of doomchecking

While doomchecking entails the frequent and potentially compulsive (Sharma et al., 2022; Mannell & Meese, 2022), checking of a particular fact, I nevertheless argue that this behaviour is instrumentally epistemically valuable as it, ceteris paribus, leads to knowledge-acquisition.Footnote 13 First, however, note that akin to doomsurfing, doomchecking occurs on a platform deemed trustworthy by the agent. While this can allow her to avoid epistemically hostile environments such as social media platforms, it also leads doomchecking to be sensitive to the similar personalisation problems discussed in the previous section. After all, when an agent uses a search engine to check particular facts, the results may be misleading as the algorithm panders to the agent’s online profile. Yet recall that a doomchecking agent need not read the articles that result from her frequent search action. That is, while this agent may have acquired a false belief by trusting the wrong sources, or has her inaccurate understanding of a complex topic enforced through her personalised results, doomchecking itself is unlikely to lead to the acceptance of conspiracy theories or wildly inaccurate understandings of certain topics or events. It may happen that an agent who is on the fence about man-made climate change and googles whether it is a hoax, would be convinced if her top results indicate that man-made climate change is indeed a hoax. However, it is more likely that an agent would have to consume enough misleading information to counterbalance the previously consumed accurate reporting on the topic.Footnote 14 Doomchecking, then, can lead to accepting falsehoods, but the danger of epistemic damage is limited as an episode of doomchecking is constrained to checking one particular fact or claim.

When the agent does employ trustworthy sources, one may nevertheless argue that doomchecking does not lead to knowledge-acquisition as the agent already possesses a true and justified belief referring to the relevant state of affairs, which may not have changed (significantly). After all, doomchecking refers to frequently checking a previously checked fact, generally using the same platform previously employed. As such, one may refer to the literature on of repeated checking to argue that doomchecking merely leads one to acquire further justification for a particular belief (Woodard, forthcoming) or would not improve one’s epistemic position at all (Friedman, 2019), as the information upon which the doomchecker bases her belief has not changed.

However, on the cited accounts of repeated checking, the epistemic agent checks previously checked information as she considers that her previously acquired belief may have been false (e.g., checking whether one really turned off the stove). She thereby checks her prior belief by checking the relevant information (that the stove is off). In contrast, the doomchecker, ceteris paribus, knows that at time t, p is true yet, as doomchecking concerns checking facts related to current events, i.e., facts that are likely to change, the doomchecker does not know whether p is still true at t+1. As such, the doomchecker does not check whether her belief that p at t was true. She rather checks updated information related to p to determine whether p is true at t+1.

The doomchecker’s belief acquired at t+1 is thereby distinct from the belief acquired at t. For example, one may have the belief that at time t, n people have been killed in the Russian invasion of Ukraine. If one doomchecks this fact again, even when only an hour has passed, she acquires the novel belief that at t+1, n+m people have been killed. Moreover, given the potential changeability of n, the belief that at t+1, n+m people have been killed remains a novel belief even when the number of fatalities has not changed (m = 0). Likewise, one may frequently check whether a verdict has been reached in an important court case. While at t to tn one would acquire the distinct beliefs that at this time no decision has been made, at tn+1 one acquires the belief that a verdict has been reached (and plausibly what this verdict entails).Footnote 15 In short, what is true at t may not be true at t+1, thereby making the belief acquired at t distinct from the belief acquired at t+1. So, even when one argues that p being true at t offers some justification for taking p as true at t+1, the doomchecker still acquires a novel belief. Ceteris paribus, then, doomchecking allows a responsible epistemic agent to acquire novel epistemic goods.

Note that it seems plausible that from a certain frequency, the epistemic value of doomchecking becomes negligible, as it is unlikely for another groundbreaking event to have occurred in, say, the last ten minutes or seconds. However, it is not inherent to the behaviour that one doomchecks with this frequency. After all, in the court case example, once the doomchecker knows that a verdict has been reached, she would not keep checking whether a verdict has been reached. Likewise, then, if a doomchecker knows that COVID’s r-value is only updated once a day, she will not doomcheck this r-value after the daily update.Footnote 16 In other words, if a doomchecker is aware that it is highly unlikely that there are updates to a topic of interest or that a novel distressing event has occurred, she is also unlikely to doomcheck. However, during a permacrisis and within our sociotechnical environment, where developments are reported on almost instantaneously, it is often plausible that a novel development or event has been reported on since the last moment one checked one’s preferred news website.

Nevertheless, due to its limited epistemic scope, I argue that doomchecking is, ceteris paribus, less epistemically valuable than doomsurfing: while doomsurfing tends to entail long-lasting deep-dives into particular topics, leading the agent to acquire a multitude of novel true beliefs or understanding, the activity of doomchecking ends once the belief the agent intended to acquire is acquired. So, if the agent employs reliable sources when engaging in these behaviours, doomsurfing is likely to result in the acquisition of more, or more valuable, epistemic goods than doomchecking.

4 Doombehaviour’s advisability

As noted, doombehaviour is generally considered to be unfavourable. For a large part, this is due to the potential prudential cost that accompanies enacting these behaviours. Recall that doomscrolling and doomsurfing induce prolonged negatively valenced affective states and are linked to an increase in depression or anxiety. Moreover, as frequently checking distressing facts has previously been categorised as doomscrolling or doomsurfing in studies exploring their prudential consequences (Anand et al., 2022; Mannell & Meese, 2022), these consequences can be applied to doomchecking as well. The initial advice would thereby be to limit doombehaviour altogether to avoid the potential prudential harms the behaviour may induce. This is enforced by the way in which doomscrolling and doomsurfing are often discussed interchangeably (e.g., Price et al., 2022; Roose, 2020) or grouped together as problematic news consumption (McLaughlin et al., 2022): if one form of doombehaviour is advised against, they all are.

However, this advice neglects the initial epistemic motivation behind doombehaviour: those who engage in doombehaviour often do so as they aim to be informed. In this section I discuss how the potential instrumental epistemic value of the categories of doombehaviour can inform the behaviour of those who aim to acquire knowledge on current events, taking the negative prudential consequences of this behaviour into account. I first argue that doomscrolling ought to be avoided from this point of view, while the opposite is the case for doomchecking and doomsurfing. Rather, akin to other epistemic behaviours that have negative prudential effects, doomsurfing and doomchecking may not merely be epistemically worthwhile, but even admirable. I argue that this is the case up until doomsurfing and doomchecking become dispositions which induce episodes of depression or anxiety. While one may be willing to pay the steep price of depression or anxiety in their aim to be informed, the negative effects these states can have on one’s epistemic abilities can counteract this aim. In other words, doomsurfing and doomchecking may be advisable when the agent is epistemically motivated and when the prudential consequences of these behaviours are limited to temporary negatively valenced affective states.

4.1 Motivating doombehaviour

Given the distinct instrumental epistemic values of the categories of doombehaviour, whether one ought to enact the behaviour to accomplish one’s goal of being informed differs. As doomscrolling tends to produce unjustified beliefs, true or false, its epistemic value does not seem to justify the potential prudential cost of enacting it. Moreover, where an agent is not epistemically motivated, merely aiming to upregulate her mood through social media engagement, the negatively valenced information, abundant due to the permacrisis, that is presented on the relevant platforms also contradicts this prudential goal. As such, an epistemically motivated agent ought to reduce or reject doomscrolling.

In contrast, doomsurfing and doomchecking, ceteris paribus, adhere to the epistemic norms of acquiring truths and avoiding falsehoods. After all, if one initially chose a trustworthy source to check the relevant fact, the source is likely to be trustworthy upon doomchecking the fact. Additionally, as one employs multiple sources during the research performed during doomsurfing, one is less likely to accept misinformation presented on one untrustworthy website.Footnote 17 Moreover, the immersive quality of doomsurfing is likely to lead to the acquisition of in-depth knowledge one would not have acquired through orthodox news consumption, i.e., merely reading the paper or watching the evening news.

The negative prudential effects of doomchecking and doomsurfing are not sufficient to limit their enaction from an epistemic point of view. Situations where many would prefer to know a distressing truth over not knowing it (e.g., knowing about one’s cheating spouse) are plentiful. Moreover, acquiring knowledge despite being aware of the distress this knowledge may cause, can reflect a love or positive evaluation of epistemic goods, where this stance and acting upon it is deemed fitting, virtuous, or admirable (e.g., Baehr, 2011; Brady, 2006; Zagzebski, 1996, 2003). One example of this is someone researching the effects of the transatlantic slave trade who may become emotionally distressed due to the harrowing content and its ongoing impact on millions of lives. The negative prudential effects of this research do not detract from its epistemic value and, when they are accepted by the agent as she deems the distressing knowledge sufficiently worthwhile to experience these negative effects, this knowledge-acquisition would be deemed admirable on this account.

Moreover, the preoccupation that characterises doomchecking and immersion characterising doomsurfing do not change the value of the knowledge-acquisition process—as noted, they may rather function as useful states of mind when one is epistemically motivated. After all, we may think of endless examples of epistemic agents being immersed in, or preoccupied with, acquiring knowledge on distressing yet important topics, where this research would be described as epistemically worthwhile or even admirable. Recall the agent researching the effects of the trans-atlantic slave trade. Being immersed in this research rather than forcing oneself to continue reading reflects an epistemic motive that fits with the importance of the acquired knowledge. I.e., losing herself in this research reflects the affectively experienced positive evaluation of the importance of the information consumed. Similarly, an agent preoccupied with the results of a study they designed may frequently check the developments of the study to know and report on its progression, even when the study is not developing as predicted, whereby the lessened likelihood of publishing the results is distressing. This behaviour is not merely epistemically worthwhile; it can even considered to be admirable as the agent continues to work diligently to acquire and report the truth, despite this process being distressing. The continued preoccupation with the study not only aids the agent in performing this behaviour, as the lack of publication prospects may otherwise demotivate her diligent behaviour, but also reflects that the agent cares about the information they consume. Likewise, then, doomsurfing and doomchecking may be deemed epistemically worthwhile, or even admirable if one knowingly accepts the potential distress that accompanies these activities to acquire valuable epistemic goods.

This trade-off between the epistemic goods and prudential costs is however not always sustainable when it comes to doombehaviour in a socio-technical environment during a permacrisis. Engaging in doombehaviour can quickly result in a disposition, and regularly engaging in doombehaviour is linked to experiencing episodes of depression or anxiety. Even for those who value being informed to such an extent that they are willing to experience such episodes, the effects of these episodes on one’s epistemic abilities and situation ought to make them reconsider. In what follows I discuss the negative epistemic effects of depressive episodes and anxiety, arguing that those who love or value epistemic goods ought to protect their mental health to avoid hindering their acquisition.

4.2 Assessing the epistemic consequences of depression and anxiety

As discussed, dispositional doombehaviour is linked with an increased probability of experiencing depressive or anxious episodes. Whether doombehaviour does in fact lead to depressive or anxious episodes has been argued to differ from person to person: if one has a pre-disposition to experience depressive or anxious moods, doombehaviour is likely to activate this disposition (Price et al., 2022). In the remainder of this section I argue that experiencing depressive or anxious moods negatively affects one’s ability to adhere to the truth norm, as well as one’s ability and motivation to acquire understanding, thereby reducing the instrumental epistemic value of doombehaviour for those who are predisposed to experience depressive episodes or anxiety.

First, depressive episodes are often characterised by feelings of alienation with regards to others and future goals (e.g., Jacobs, 2013; Ratcliffe, 2014), supporting the likelihood that one may become less inclined to engage with one’s intellectual cohort, as suggested by Brogaard (2014). Engaging with one's peers can have a positive epistemic effect by providing a diversity of perspectives, which can lead to a better understanding of a topic. Additionally, discussing and debating ideas with others can help to identify and challenge one's own biases, in addition to potentially unjustified or false beliefs. Where one feels alienated from others and unmotivated to seek social contact due to a depressive state brought on by doombehaviour, the epistemic benefits of social interaction are limited, negatively affecting one’s ability to acquire truths while avoiding falsehoods.

Second, the noted alienation from future goals minimises one’s motivation to work towards epistemic goals that may be time-consuming to acquire. Moreover, as one's emotional responses to the environment seem stifled for the depressed agent, possibilities to acquire epistemic goods can be experienced as less inviting, or as more difficult or effortful to perform (e.g., Buyukdura et al., 2011). When doomsurfing or doomchecking leads to depressive moods, then, these practices indirectly lead to a decreased motivation to acquire further epistemic goods. The good in question may either seem too time-consuming or effortful to acquire, or the possibility to acquire the epistemic good may not even be perceived due to a lack of experienced curiosity or interest.

While this effect is applicable to potential epistemically valuable topics in general, it can also affect the desire to be informed on current events, illustrated by the news fatigue that occurred due to the negative effects on mental health experienced in response to COVID-19 related news: rather than merely limiting doombehaviour or news consumption on the distressing topic, many avoided news consumption altogether (Fitzpatrick, 2022; Mannell & Meese, 2022).

Other negative epistemic effects can occur when one experiences an anxious mood. Anxious moods direct one’s attention to the intentional object of one’s anxiety (e.g., Barrett & Bar, 2009; Brady, 2016), i.e., the topic one doomsurfs or doomchecks, inducing the preoccupation that characterises doomchecking and may motivate doomsurfing.Footnote 18 Such preoccupation makes one less open to exploring other important epistemic goals. I have already argued that this need not reduce the epistemic value of the information acquired; the topic is non-trivial and in flux, meaning one still acquires a new belief upon doomchecking the topic in question. However, another effect of anxiety can make this preoccupation epistemically disadvantageous.

Anxious moods tend to induce the belief or feeling that one is unable to cope with (potential) negative events or situations, which involves an overestimation of the danger or negative effects of certain (possible) situations or events, or an underestimation of one’s abilities (e.g., Mennuti et al., 2012; Reilly et al., 1999). This thereby undermines the truth norm: the underestimation of one’s abilities or overestimation of the danger or negative consequences of an event or situation is inaccurate. Anxious moods thereby motivate the agent to hold false beliefs. Additionally, underestimating one’s abilities can negatively affect one’s confidence in one’s knowledge, leading one to doubt true and justified beliefs. In other words, anxious moods can undermine the truth norm by inducing false beliefs, on top of losing previously held true beliefs.

Moreover, where this effect is combined with the preoccupation that anxiety induces, one may overestimate the danger of an event or the negative events that may occur. This overestimation can thereby increase the frequency with which one doomchecks, moving away from the balance discussed in Sect. 3.3. If one overestimates the danger of something disastrous to occur, after all, then one is also likely to doomcheck too often, considering that the epistemic value of doomchecking rests on the plausibility of the relevant fact to have changed.

Given these effects, if an agent is pre-disposed to experience depressive or anxious moods, the initial epistemic fruits of engaging in doombehaviour can be counterbalanced by the negative epistemic consequences of the depressive episodes or anxiety that regular doombehaviour can induce. This thereby further specifies the guidelines of doombehaviour, as discussed in the following subsection.

4.3 The guidelines of doombehaviour

Recall that previous advice concerning online news consumption during the permacrisis entailed minimising doombehaviour or even news consumption altogether. From the analysis presented in this paper, however, we can formulate advice that takes the negative prudential effects of doombehaviour into account, without ignoring the agent’s positive evaluation of epistemic goods that allow her to be informed on current events.

First, due to doomscrolling’s potential to present the agent with misinformation and disinformation, engaging in this practice is not epistemically worthwhile, and may even be epistemically detrimental. When this is combined with its negative prudential effects, then, doomscrolling ought to be minimised. In contrast, the negative prudential consequences of doomchecking and doomsurfing could potentially be accepted as the price to pay for acquiring valuable epistemic goods or being informed, where the preoccupation and immersion that characterise these activities aid the agent in achieving their goals. Moreover, where one does accept the prudential costs due to one’s love for, or positive evaluation of, these epistemic goods, the behaviour may even be admirable (Baehr, 2011; Zagzebski, 1996, 2003).

However, if an agent’s doomsurfing or doomchecking becomes a stable disposition, she ought to be aware of signs of anxiety or depression, regularly checking whether her negatively valenced mood subsides soon after concluding her doombehaviour, or whether it lingers and may even be pathological. Additionally, habitual doombehaviour ought to be avoided altogether where one is predisposed to experience anxious or depressive moods. In other words, one ought to take one’s disposition to experience depressive or anxious moods into account to determine whether regularly engaging in these practices is epistemically worthwhile. In short, while doomscrolling ought to be avoided, if one can doomsurf and doomcheck on trustworthy platforms without thereby experiencing prolonged anxious or depressive moods, then acting on one’s epistemic motivation through these behaviours is epistemically worthwhile.

5 Conclusion

This paper presented an initial analysis of doomscrolling, doomsurfing, and doomchecking as distinct and novel, yet increasingly prevalent, epistemic behaviours. As these behaviours come with prudential costs, negatively affecting one’s mood or even mental health, advice aimed at reducing these prudential costs has focussed on reducing doombehaviour or news consumption altogether. By arguing for more fine-grained concepts to categorise doombehaviour, I noted that the resulting advice would also be more fine-grained, taking into account the negative prudential consequences of doomscrolling, doomchecking, and doomsurfing without ignoring their distinct epistemic values.

I argued that doomscrolling ought to be avoided due to the inherent unreliability of its platform, while doomchecking and doomsurfing can be epistemically worthwhile when agents employ trustworthy news websites. However, agents who value being informed, thereby accepting the distress that follows engaging in doomchecking or doomsurfing, ought to assess whether the relevant behaviour induces episodes of depression or anxiety, as these states are likely to impair their ability to enact the epistemic behaviour required to become or remain informed on these and other topics of interest in the future. In other words, if an agent aims to be informed on current events, motivating the frequent or long-lasting consumption of distressing information in online spaces, she should avoid doomscrolling yet can acquire non-trivial knowledge and understanding by, respectively, doomchecking and doomsurfing. Until these behaviours become dispositional, that is, as this increases the risk of experiencing depressive or anxious episodes and news fatigue.

The constant availability of more or novel information related to global and local current events makes the long-lasting and frequent news consumption that characterises doomscrolling, doomsurfing and doomchecking possible and perhaps even inviting, especially when the design of the platform is meant to grab the user’s attention. As such, the discussion of the categories of doombehaviour presented in this paper opens an important door to future explorations of these prudentially harmful forms of information consumption that shape our current socio-technical epistemic landscape.

Notes

The term ‘doomscrolling’ was already in use by 2018 (Garcia-Navarro 2020).

The prudential costs here reflect the negative effects on the agent’s mental health and the experience of negatively valenced emotions, where pluralist accounts of well-being that include epistemic value are bracketed.

The qualifier that doombehaviour is merely often motivated by negative affect is in place due to the potential automaticity of these behaviours. That is, one can mindlessly open an app and perform the relevant behaviour. So, while these actions may be motivated by an affective push, they need not be in response to the agent aiming to satiate her sense of doom or uncertainty. Do however note that both the sense of doom and the automated habitual engagement with technology encourage doombehaviour to become dispositional, the relevance of which is discussed in Sect. 4.

Omitting the rare instances where, e.g., webpages take a long time to load.

One form of doomchecking deserves special attention as it appears to be ubiquitous without being related to a specific topic or event. Namely, checking whether something distressing has occurred since one last checked the relevant news application or website. This will be discussed further in Sect. “2.4”.

While information on distressing current events has been easily accessible since the introduction of online news platforms, the everchanging quality of current distressing events motivates continuous inquiry. After all, people rarely doomsurf the famine in Yemen—a crisis that has been going on for a long time and is unlikely to improve in the foreseeable future.

The exception is those who engage in doomscrolling with the aim to upregulate their mood (despite this being an ineffective method).

Note that this is a strong formulation of the truth norm as it implies that one ought to possess all beliefs that are true—an impossible task. This has been addressed by, e.g., Lynch, who suggests to reformulate the truth norm as “relative to the propositions one might consider, one [ought to] believe all and only those that are true” (2009, p. 226). Arguments on whether this reformulation should be accepted or not is outside the scope of this paper. Rather, it should merely be clear that when truth is the ultimate epistemic value, acquiring it while avoiding falsehoods is the main epistemic goal.

Note that knowledge (as justified true belief) is integrated in the truth norm, as a belief being justified stands in a positive relation to the belief being true (BonJour, 1985 p. 8). That is, a belief that p being justified is only instrumentally epistemically valuable as it makes it more likely that p is true; truth remains the fundamental epistemic value.

This is connected to examples supporting or negating the potential justification of epistemic paternalism in social epistemology: not finding out about one’s cheating spouse, or acquiring misinformation about drugs that prevents one from taking harmful substances, may protect one’s well-being despite the epistemic costs. While I take the negative prudential consequences of doombehaviour into account in Sect. 4 of this paper, I merely focus on instances where an agent may choose to engage in this behaviour as she is epistemically motivated, while being aware of the prudential costs.

While many falsehoods may be acquired due to disinformation—false information shared in order to trick the reader—false beliefs may also be acquired by consuming misinformation, which does not entail malicious intent and may simply entail overly simplified information or sensationalist reporting.

As I discuss in this section, it seems plausible that from a certain frequency, doomchecking is no longer epistemically valuable due to the minimal likelihood that the checked fact has been adjusted. However, note that the doomchecker need not be irrational: for example, when they know that COVID’s r-value is only updated once a day, they will not doomcheck this r-value after the daily update. Likewise, unless they are following a live blog on a news website, they will not continually refresh the page to check for updates.

Note that this is merely in terms of information rather than reliable evidence (Cassam 2019a).

Note that once one knows that a verdict has been reached, a doomchecker would not keep checking whether a verdict has been reached. Likewise, then, if a doomchecker knows that COVID’s r-value is only updated once a day, she will not doomcheck this r-value after the daily update.

Unless, that is, if the doomchecker engages in a similarly obsessive behaviour as the agent who frequently checks whether she really turned off her stove. That is, in cases where the agent is aware that the relevant information has not changed.

Nevertheless, as stated, where an agent employs multiple unreliable sources, such rabbit holes can rather lead to an inaccurate representation of complex topics.

Note that not all preoccupation characterising doomchecking must be due to anxiety.

References

Alfano, Mark, Amir Ebrahimi Fard, J. Adam Carter, Peter Clutton, and Colin Klein. ‘Technologically Scaffolded Atypical Cognition: The Case of YouTube’s Recommender System’. Synthese 199, no. 1 (1 December 2021): 835–58. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-020-02724-x.

Alston, W. (2005). Beyond justification: Dimensions of epistemic evaluation. Cornell University Press.

Anand, N., Sharma, M. K., Thakur, P. C., Mondal, I., Sahu, M., Singh, P., Ajith, S. J., Kande, J. S., Ms, N., & Singh, R. (2022). Doomsurfing and doomscrolling mediate psychological distress in COVID-19 lockdown: Implications for awareness of cognitive biases. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care, 58(1), 170–172. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppc.12803)

Baehr, J. (2011). The inquiring mind: On intellectual virtues and virtue epistemology. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199604074.001.0001

Barrett, L. F., & Bar, M. (2009). See it with feeling: Affective predictions during object perception. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 364(1521), 1325–1334. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2008.0312

BonJour, L. (1985). The structure of empirical knowledge. Harvard University Press.

Bradshaw, S., & Howard, P. N. (2019). The global disinformation order: 2019 Global Inventory of Organised Social Media Manipulation. Computational Propaganda Project by the Oxford Internet Institute, 27. University of Oxford.

Brady, M. S. (2006). Appropriate attitudes and the value problem. American Philosophical Quarterly, 43(1), 91–99.

Brady, M. S. (2016). Emotional insight. Oxford University Press.

Brogaard, B. (2006). Can virtue reliabilism explain the value of knowledge? Canadian Journal of Philosophy, 36(3), 335–354. https://doi.org/10.1353/cjp.2006.0015

Brogaard, B., & Smith, B. (2005). On luck, responsibility and the meaning of life. Philosophical Papers, 34(3), 443–458. https://doi.org/10.1080/05568640509485167

Brogaard, B. (2014). Intellectual flourishing as the fundamental epistemic norm. In Epistemic norms: New essays on action, belief, and assertion, edited by Clayton Littlejohn and John Turri, 11–31. Oxford University Press. https://philarchive.org/rec/BROIFA-2.

Buyukdura, J. S., McClintock, S. M., & Croarkin, P. E. (2011). Psychomotor retardation in depression: Biological underpinnings, measurement, and treatment. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry, the Neurobiology of Neurodegenerative Disorder: From Basic to Clinical Research, 35(2), 395–409. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnpbp.2010.10.019

Cambridge University Press. (n.d.). Rabbit Hole. In Cambridge dictionary. Retrieved May 20, 2022, from https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/rabbit-hole

Cassam, Q. (2019). Conspiracy theories. Polity Press.

Cassam, Q. (2019). Vices of the mind: From the intellectual to the political. Oxford University Press.

Collins - the collins word of the year 2022 is... Collins Online Dictionary. (n.d.). Retrieved December 11, 2022, from https://www.collinsdictionary.com/woty