Abstract

The method of reflective equilibrium (MRE) is a method of justification popularized by John Rawls and further developed by Norman Daniels, Michael DePaul, Folke Tersman, and Catherine Z. Elgin, among others. The basic idea is that epistemic agents have justified beliefs if they have succeeded in forming their beliefs into a harmonious system of beliefs which they reflectively judge to be the most plausible. Despite the common reference to MRE as a method, its mechanisms or rules are typically expressed in a metaphorical or simplified manner and are therefore criticized as too vague. Recent efforts to counter this criticism have been directed towards the attempt to provide formal explications of MRE. This paper aims to supplement these efforts by providing an informal working definition of MRE. This approach challenges the view that MRE can adequately be characterized only in the negative as a set of anti-essentialisms. I argue that epistemic agents follow MRE iff they follow four interconnected rules, which are concerned with a minimalistic form of foundationalism, a minimalistic form of fallibilism, a moderate form of holism, and a minimalistic form of rationality. In the critical spirit of MRE, the corresponding working definition is, of course, provisional and revisable. In general, the aim is to contribute to a reflective equilibrium (RE) concerning MRE. If it is successful, this working definition provides a better grasp of the most basic elements of the method and thereby enhances our understanding of it.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

If one were to make an inventory of the philosophical toolbox, one sensible item on the list would be the method of reflective equilibrium (MRE). However, although MRE is mentioned in many papers, in particular in moral philosophy,—sometimes in affirmation, sometimes in opposition—it is not immediately clear how this method relates to other sensible items on the list, like the usage of thought experiments, conceptual analysis, conceptual (re-)engineering or ameliorative analysis, to name a few.Footnote 1 This lack of clarity is explained, in part, by an even more pressing and general issue: despite the suggestion that MRE is in fact a method, its mechanism or rules are typically expressed in a rather metaphorical or simplified manner and therefore might be considered to be too vague.

There are efforts by the proponents of MRE to counter this critique with a clarification of the method. In the present paper I aim to supplement these efforts by providing, to my knowledge, the first informal working definition of MRE. In the critical and systematic spirit of MRE, this working definition is, of course, understood to be provisional and revisable.Footnote 2 In general, the idea is to contribute to a reflective equilibrium (RE) concerning MRE.Footnote 3 If successful, it provides a better grasp of the most basic elements of the method and thereby enhances our understanding of it (Elgin, 1996, 2017; Baumberger & Brun, 2021).

The paper proceeds as follows:

Section 2 provides an initial characterization of a method that serves as point of reference for the further inquiry. Moreover, I argue that a working definition of MRE cannot be adequately based on a specific historical account of the method.

One might object that it is in principle impossible to provide a positive definition of MRE, since the method can only be characterized in the negative as a set of anti-essentialisms. Kenneth Walden’s position could be interpreted this way (Walden, 2013). In Sect. 3, however, I argue that a purely negative characterization of MRE is unsatisfactory and that it is at least a reasonable endeavor to seek a working definition of the method.

In order to do so, we must distinguish between necessary and contingent elements of MRE. Section 4 makes this distinction with reference to two exemplary cases. The first case of a contingent element of the method is the Rawlsian idea that we should use only our considered moral judgements for MRE in normative ethics. The second case is Daniels’s claim that in order to reach a sufficiently wide RE state one must respect what he calls the independence constraint.

In Sect. 5, I present four interconnected rules of MRE and argue that each of these rules is a necessary element of the method. In Sect. 6, I argue that these four rules are also jointly sufficient for MRE, because paradigmatic MRE conceptions are included and paradigmatic approaches that are incompatible with MRE are excluded. A brief conclusion is provided in Sect. 7.Footnote 4

2 An initial characterization of the method

To begin with a very general fact about MRE, we can observe that it is proposed as a method of justification. As such it is highly prominent in moral philosophy. However, it is not limited to this discipline, or even to philosophy itself.Footnote 5 Further, there are strong claims in favor of MRE:

“Indeed, it is the only defensible method: apparent alternatives to it are illusory.” (Scanlon, 2002, p. 149).

It is far from clear, however, precisely what is meant by justification in this context, and there is serious potential for misunderstanding. In epistemology, for example, “justification” mostly refers to a kind of justification that figures in the analysis of knowledge as justified true belief. Thus, a justification is understood to provide a warrant for beliefs, such that any true belief would be an instance of knowledge if it is additionally justified. However, the most elaborate accounts of MRE do not claim that MRE provides this kind of justification (see for example Daniels, 1996; DePaul, 1993; Elgin, 1996, 2017; Baumberger & Brun, 2021; Kauppinen & Hirvelä, 2022).Footnote 6 At the same time, however, justification via MRE is not just a persuasive rhetorical device that one can identify empirically in dialogical practice. Because it is bound to what an epistemic agent actually should believe, it has an epistemically normative dimension. MRE aims at beliefs (or, alternatively: commitments, acceptances, credences…)Footnote 7 that are justified for a specific epistemic agent. It aims at a kind of internal justification, which is seen as a form of rational entitlement to believe only in light of one’s beliefs and not according to some criterion that is external or inaccessible for the epistemic agent. This is not meant to imply that externalist accounts of justification, for example, are wrong; on the contrary, they might be justified by the use of MRE itself. Justification that can be attained via MRE is simply of another type (for pluralism on justification see, for example, Meylan, 2017) and refers to a justification that epistemic agents should provide for themselves or in dialogue if they are wondering or arguing what to believe. Thus, if some kind of inner monologue is included, the kind of justification MRE aims at can be also called “dialectical justification” (Kauppinen & Hirvelä, 2022).

The basic idea is that epistemic agents have justified beliefs if those beliefs are part of a RE. Epistemic agents achieve a RE iff they succeed in forming their beliefs into a harmonious system of beliefs which they reflectively judge to be the most plausible. In order to arrive at a RE, one must scrutinize one’s beliefs in an integral manner and mutually adjust theoretical principles and judgements at all levels of generality.

From this brief characterization, which will be expanded below, it immediately follows that one can make a distinction between the state of RE and MRE: MRE aims at achieving the state of RE by offering what one could call a RE process.

According to John Rawls, a RE state concerning justice is reached.

“[…] after a person has weighed various proposed conceptions [of justice] and has either revised his judgements [about justice] to accord with one of them or held fast to his initial convictions (and the corresponding conception).” (Rawls, 1999, p. 43).

While pursuing RE, it is important, according to Rawls,

“[…] to be presented with all possible descriptions to which one might plausibly conform one’s judgements together with all relevant philosophical arguments for them.” (Rawls, 1999, p. 43).

There are, at least, two important points one can extract from these quotes. According to the first quote, there is no type of judgement in the RE process which is immune from revision: in case more theoretical judgements conflict with more intuitive ones, both can in principle be revised in order to achieve consistency and, where possible, coherence as a criterion for a plausible epistemic position.Footnote 8 According to the second quote and insofar as arguments are ultimately based on premises that may be considered hypotheses or parts of theories, it is necessary to include in the RE process all beliefs, theories and hypotheses that are relevant in light of the current inquiry. This requirement is commonly referred to as the need to strive for a wide RE (in contrast to an overly narrow RE)Footnote 9 (Rawls, 1999, p. 43 f., 1974; Daniels, 1979). The requirement for a wide RE can be interpreted in two non-exclusive but rather complementary ways:

-

1)

One must include beliefs about the relevant opinions of epistemic peers or experts (including, plausibly, their respective track record) (see Rawls, 1974, p. 7 f.). For the academic context this may mean that one should also include proposed theories that are deemed relevant, even if one does not accept them initially. With respect to the issue of justice, according to Rawls, this especially concerns the theories “[…] known to us through the tradition of moral philosophy […]” (Rawls, 1999, p. 43).

-

2)

One must include beliefs that are not directly related to the specific inquiry but nevertheless have implications for directly relevant beliefs. These beliefs must be included as long as their inferential connections can be revealed through adequate reflection. Some of these beliefs may belong to what Norman Daniels calls “background theories” (Daniels, 1979, p. 258).Footnote 10

Thus far I have focused on the Rawlsian account of MRE. This is appropriate since Rawls coined the name “RE” (Rawls, 1971, 1999; see Gališanka, 2019) and his philosophy is thus a natural starting point for further inquiry into the concept of MRE. However, Rawls himself claimed that MRE is common and has been used (or followed implicitly) throughout much of the history of philosophy. He explicitly refers to the following list of diverse thinkers, who, in his judgement, reflectively employed and advocated the method to a certain degree: Aristotle, Henry Sidgwick, Nelson Goodman, Willard Van Orman Quine and Morton White (Rawls, 1999, pp. 18, 45, 507). He briefly also mentions the Socratic spirit of MRE and a connection to what John Stuart Mill regarded as a feasible philosophical proof (Rawls, 1999, pp. 108, 507).

Typically, only Rawls’s reference to Goodman is noted in the literature, presumably since Rawls refers to Goodman’s proposed methodology for justifying accounts of adequate logical reasoning as an exemplification of MRE at the point where he introduces the method (Rawls, 1999, p. 18). Quite often, it is prominently claimed that MRE therefore originated in Goodman’s philosophy (e.g., Baumberger & Brun, 2021; Daniels, 2020; Walden, 2013). However, there are at least two reasons to question this claim:

-

1)

If Rawls is right in referring to Aristotle or Sidgwick as practitioners (and thinkers) of MRE avant la lettre, they—and other possible proponents of MRE—are clearly historically prior.

-

2)

Rawls’s account of MRE originated in his work around 1950, which is primarily accessible in his dissertation and a subsequent paper (Rawls, 1950, 1951; see Mandle, 2016; Reidy, 2016; Botti, 2019; Gališanka, 2019). As the period when these texts were written is essentially the same time when Goodman (alongside with Quine and White) developed the ideas published in Fact, Fiction, and Forecast (White, 1999), a reasonable interpretation is that the basic idea of MRE was independently arrived at by multiple scholars and its explicit (re-)formulation might be regarded as an early offspring of post-war philosophy.

Now, this does not mean that one need not pay close attention to Goodman’s account of MRE (or any other).Footnote 11 Nor is this only interesting for the history of philosophy. Rather, it shows that a definition of MRE cannot easily be settled on the basis of a specific historical account.

Moreover, the most elaborate explicit accounts of MRE—alongside Rawls’s, for example, those proposed by Norman Daniels, Michael DePaul, Folke Tersman, and Catherine Z. Elgin—disagree at least in some respects and are rather vague at least with respect to MRE’s core rules or mechanisms.

With regard to the latter problem, one can observe that there is a growing awareness and effort to resolve the vagueness by providing formal interpretations of the method. However, this is still an ongoing endeavor with few available results (Thagard, 2000; Welch, 2014; Freivogel, 2021; Beisbart et al., 2021). With regard to these and prospective formal interpretations, there is the open question of their adequacy. In order to answer this question, we must refer to an informal interpretation of MRE.Footnote 12

However, if we cannot avoid referring to an informal interpretation of MRE, we are confronted with the other aforementioned problem: the best informal accounts of MRE seem to disagree to at least some extent and it is unclear how they relate to each other. Therefore, we need a better informal understanding of MRE. This paper contributes to this task by seeking a minimalistic working definition of MRE that covers all paradigmatic informal conceptions of MRE and thus explains how they hang together.

3 Is it possible to define MRE?

Doubts have been raised as to whether one can in fact provide a positive definition of MRE. Kenneth Walden prominently claims:

“[…] the method of reflective equilibrium is not, exactly, anything. It is a mistake to try to give a positive characterization of reflective equilibrium […]” (Walden, 2013, pp. 243, 244).

Does this mean that, whenever we try to provide a justification for a belief, we are already following MRE? Anything goes? This would be an uncharitable interpretation of Walden. While he does want to stress that we cannot provide a positive characterization, he himself still aims for a kind of ‘negative theology’. We should be especially careful not to identify MRE with

“[…] a concern with a particular species of data, particular procedures and methods, or even a particular conception of normative success. Instead, it should be understood as the denial of essentialism about just these matters—as a form of anti-essentialism about our epistemic inputs, methods, and goals. Practitioners of reflective equilibrium deny that we can say much of anything substantive in advance of inquiry, and they think of their ‘method’ as whatever is left over of our ordinary thinking once we have purged these essentialist bogeys. In short, reflective equilibrium is what it isn’t.” (Walden, 2013, p. 244).

While I largely agree with Walden concerning these anti-essentialisms, such a purely negative characterization is unsatisfactory. It excludes so little that nearly anything goes. It does not rule out, for example, ways of “ordinary thinking” that clearly conflict with our initial beliefs about a RE process. If we justify a belief by inferring it from what we hold to be an indubitable and certain truth, which we dogmatically and uncritically accept, then we are not following MRE. If we justify a belief by bringing it into accordance with a specific theory but do not reflect on problematic assumptions of this very theory, we are not following MRE. Thus, MRE does seem to involve more than simply these specific forms of anti-essentialism.

Of course, one could try to expand the negative characterization of MRE by excluding other positions or practices as well. Any integrated account of MRE will involve such a list of exclusions. However, a purely ‘negative theology’ has problems of its own: Why can we accept these negative statements in advance of inquiry but we cannot accept any positive ones? On which grounds do we accept these statements? Additionally, if we take seriously that MRE is a method, we should be able to offer some rules that provide guidance for action, whereas a negative characterization can only provide guidance for non-action. Since MRE figures prominently as a method for justification in the public and political realm and is, according to some forms of liberalism, a requirement for public reasoning, it should be able to offer action guidance. A positive characterization or even a working definition of MRE thus would be desirable if it is attainable.

It is not entirely clear whether Walden would argue that every attempt to find a positive definition of MRE is doomed to fail in principle.Footnote 13 Nevertheless, two reasons might be offered to support such a claim about the (lack of) attainability of a working definition of MRE:

-

1)

We cannot abstractly determine the method in advance of inquiry; rather, it can only be determined concurrently with and for the purpose of a specific inquiry, such that it will vary with the objects and aims of the respective inquiries.Footnote 14

-

2)

One can question whether the conceptions of MRE that are brought forward in fact share a conceptual core that would allow for such a working definition, or whether they rather exhibit a kind of family resemblance.

Let us begin with the second reason. It is clearly possible that conceptions of MRE that we reflectively judge to be paradigmatic do not share a conceptual core. If we do not want to discard a supposed conception of MRE as misguided (or make ad hoc adjustments), an adequate and general working definition would be impossible. How can we know if this is the case? One viable strategy is simply to attempt to formulate a conceptual core while remaining open to the possibility that the best effort to do so might fail.

The first reason might be considered a reason to not even attempt to define MRE in an abstract way. Intuitively it seems quite plausible that the form of a RE process will vary with the specific aim or object of inquiry. Think of Rawls’s specification of the method with regard to the task of public justification within sufficiently just liberal democracies (“full reflective equilibrium”) (Rawls, 1995, p. 141, 2001, p. 31 f.; Daniels, 1996, pp. 144–175; Walden, 2013, p. 255). However, first, even here all adequate specifications of MRE might share a more abstract conceptual core, and second, if one subscribes to MRE, even here not every form of inquiry is suitable for determining what specifications of MRE are adequate for and within the respective inquiry. What is methodologically justified with respect to a specific aim and object of inquiry must then be justified via MRE on a more primitive or general level from which we can assess the adequacy of the specification without presupposing it. It is this general level that the definition of MRE we seek is concerned with. I will elaborate on this idea in the next section.

4 Contingent elements of MRE conceptions

There are some elements of MRE conceptions which are quite commonly interpreted as essential elements when they are in fact, at most, contingent elements of MRE. Elements can be contingent when their inclusion depends on a justification via a more primitive version of MRE in the first place (where this justification is not self-defeating). Often, these contingent elements are restricted to a specific aim and object of inquiry, but this need not be the case.Footnote 15

One important example of a contingent element of the method that is often taken to be necessary is Rawls’s idea that we should only accept considered moral judgements as input for the RE process in normative ethics. For Rawls, ‘considered judgements’ means beliefs that are formed under circumstances in which our moral powers (for his purposes, especially the sense of justice) are not distorted. According to Rawls, such a distortion is likely to happen when we are not interested in the truth or correctness of a judgement, when we are upset, partial, or feel uncertain about this judgement. Therefore, we should exclude beliefs formed under these circumstances from the RE process in normative ethics. Here, I am not concerned with the question whether such a specification of MRE is justified or not. Rawls’s condition of including only considered moral judgements is criticized even by staunch supporters of MRE (for a critical treatment of this question see DePaul, 1993, p. 17 f., 128; Elgin, 1996, pp. 101–106; Rechnitzer & Schmidt, 2022). Instead, I would like to point out that the specification regarding considered judgements depends on a more primitive version of MRE. Since there are epistemic peers who question whether the specification is adequate, we can imagine Rawls, as a proponent of MRE, responding to the objections by providing a justification for this modification of the method via MRE. And for this very justification it would be adequate not to presuppose and apply the filtering process for considered judgements, if this is feasible without thereby ruining the RE process. Indeed, there are no good reasons to assume that such an RE process would be defective in any obvious way. Then whether or not he is right about the exceptional role of considered judgements depends on a more primitive version of the method and the weighed beliefs of the epistemic agents who are concerned with this matter. Thus, even if we think that limiting input to considered judgements is a justified element of a RE process in normative ethics, it is a contingent element. If we do not respect the exceptional role of considered judgements, this does not automatically mean we are not following MRE.

The last example was concerned with a contingent element of MRE that was restricted to a specific area of inquiry, namely normative ethics. Not every contingent element of MRE is restricted in this sense, though. An example for such a case might be Daniels’s proposal of an independence constraint. The basic idea behind the independence constraint is as follows: Let’s imagine we accept a theory, for example a theory of justice, because it accords with our beliefs about the topic. Now, as we want to achieve a wide RE, we ask ourselves what—apart from the agreement with our beliefs about justice—speaks for this specific theory (and what speaks against it), and it turns out that all the arguments are ultimately based on premises that are identical with the beliefs concerning justice we have already considered. We did not actually expand our set of beliefs involved in the RE process, so should we regard this as achieving a RE state or discard it as an equilibrium that is too narrow? Daniels contends that we should do the latter, since we should only accept an equilibrium as adequately wide if the set of beliefs that support a theory in the background is somewhat distinct from the set of beliefs that are directly connected with the theory. This is the independence constraint (Daniels, 1979, p. 259ff, 1980, pp. 85–100; see also Knight, 2023). Though Daniels is concerned primarily with MRE in normative and applied ethics, one can conceive of the independence constraint as a constraint on general inquiry via MRE. Other proponents of MRE, however, either do not mention such a constraint or reject it based on systematic grounds (DePaul, 1993, p. 20 ff.). This is, again, not the most relevant aspect for the present purpose. The more important question is whether we would expect Daniels to have employed a version of MRE for the justification of the independence constraint which itself does not presuppose the independence constraint. If so, it is a contingent element of the method, although it is not restricted to a specific area of inquiry.

Other contingent elements will include, among others, specifications concerning the exact group of epistemic agents that can be the users of MRE, the exact epistemic value that MRE contributes to, specifications regarding which doxastic states should be considered as the input for the method, and so on.

At this point, I want to briefly address a potential objection to the idea that proponents of MRE should use a more primitive version of MRE to justify specific versions of the method that contain contingent elements. How can we justify the elements of the more primitive version of MRE? On pain of infinite regress, we cannot always simply refer to an even more primitive version of MRE for this task. However, the move to a more primitive version in some cases does not include a commitment that would demand such an ominous strategy. At some point, proponents of MRE should accept that a minimalistic version of MRE must be justified by itself. Wherever possible, we should avoid presupposing elements of MRE when they need to be justified, but some things must be presupposed for the very endeavor of justification via MRE. The quest for a definition of MRE is simply a quest to identify these necessary presuppositions.

It is not epistemically ideal that proponents of MRE have to rely on an abstract version of the method to investigate whether it can be justified at all. However, it is acceptable since a successful self-application is unavoidable for any method of internal justification. If we were to use a different method for this task, we would ultimately rely on this other method. Moreover, a self-application of MRE does not simply beg the question whether it is justified. Such a self-application of the method involves the consideration of every relevant criticism of MRE, and its conclusion remains open—one possible result is that MRE ultimately defeats itself. This shows that MRE, though based on a rather unreflective acceptance in the first place, can progress to a reflective and critical acceptance. Indeed, it can be seen as a methodological account of critical thinking. If we judge this to be a valuable mode of thinking, especially in the public and political sphere, it is a cultural achievement that needs to be properly maintained.Footnote 16

5 Necessary elements of MRE

In this section, I propose a list of four elementary rules that jointly constitute MRE. These are necessary rules; if one of these rules is omitted from a justificatory process, this process is in conflict with MRE, and if one does not follow all of these rules, one does not follow MRE. These rules are not understood to be strictly separate; rather, they are closely interlinked. Considering these rules separately primarily serves to provide a more tangible illustration.

According to MRE these rules are in force for epistemic agents if they want to justify a belief epistemically or ask themselves what they should believe only on epistemic grounds.Footnote 17 We need not determine the exact specification of the epistemic agent, whether it must be a natural person or if it can be a group of persons (see also Sect. 5.1).

Epistemic agents can start the RE process explicitly or implicitly at any time, such as by asking if a specific belief or hypothesis is justified, or how to resolve a conflict between two or more beliefs, or how to think about a specific topic. The RE process stops (provisionally and automatically) if the epistemic agent abandons the inquiry or succeeds in achieving RE. The process can begin again at any time, especially if new relevant beliefs emerge or changes occur in the existing belief system.

While the exact order of the following rules is irrelevant once the RE process has started, I think it might be natural to order them as I do here.

5.1 Minimalistic foundationalism

The first rule concerns the doxastic states that form the foundation of the RE process. Minimalistic foundationalism can be stated as follows:

Justification via MRE is tied to the epistemic agents’ own beliefs and evaluations. Epistemic agents may (only) include beliefs in the RE process which they themselves actually happen to hold. They are also entitled to include hypotheses or theories they deem to be relevant or worth considering.

One might object that this formulation of the MRE does not pay enough attention to the social dimension of justification, since only the beliefs of the epistemic agent are allowed to enter the RE process. However, the social dimension is accounted for due, at least, to the following reasons:

-

1)

Naturally, the beliefs of the epistemic agent will include beliefs about the beliefs of other epistemic agents, including attitudes towards the content of these beliefs. An important group of these epistemic agents will be agents one regards as experts in a given area.

-

2)

Epistemic agents might be not only natural persons but also groups of persons or institutions. Courts would be an example for the latter.

-

3)

In specific instances a justification provided by a successful application of MRE by one epistemic agent will and should inform the MRE application of other epistemic agents—for instance, according to Rawls, in the exercise of public reasoning (see for example Rawls, 2005, 2001).

Additionally, this rule allows for the inclusion of hypotheses or theories, including hypotheses or theories the epistemic agents have not considered before the inquiry but now consider for systematic reasons. Of course, it might also be possible that the epistemic agents have developed a doxastic attitude towards the respective hypotheses or theories, which would entail that they can be included in any case. There are at least two reasons that epistemic agents might want to include hypotheses and theories they do not accept initially:

-

1)

The RE process is actually concerned with the justification of theories or hypotheses. The epistemic agents assume, for example, that one might justify theoretical elements such as moral principles or scientific laws that can help explain our beliefs and thus consider suitable candidates, even if they do not receive initial acceptance.

-

2)

The epistemic agents believe that relevant evidence, (expert) testimony, or some other factor supports a theory or hypothesis that does not receive initial acceptance.

One might go even one step further and make the inclusion of theories a requirement, since paradigmatic MRE accounts, such as Rawls’s, focus on the iterative adjustment of theories and beliefs (Beisbart et al., 2021, p. 456). However, I am skeptical of this requirement since not every inquiry with MRE, especially outside the academic context, will involve elaborate theories or something like theory choice (see, for example, Elgin, 1996, p. 103, 2014, 2017, pp. 69–73).Footnote 18

Further, minimalistic foundationalism does not preclude the search for new or relevant beliefs in the course of the RE process. Strictly speaking, such a search will (in most cases, where there is no excessive time pressure) be mandated by the rule of moderate holism (Sect. 5.3). A RE might ultimately also include the belief that the epistemic agent first has to gather more experiences or evidences with respect to the current inquiry.

Furthermore, this rule highlights that all kinds of beliefs that the epistemic agent holds can in principle enter the RE process. At the very basic level of MRE there is no filtering process that excludes beliefs of the epistemic agent that are not well-considered or otherwise privileged (see Sect. 4).

Regarding the qualification of this foundationalism as minimalistic, many proponents of MRE adopt, in Laurence BonJour’s terminology, a (very) weak foundationalism according to which some beliefs at the beginning of an inquiry might already possess some degree of credibility or justification, but that degree is insufficient for achieving one’s epistemic goal (e.g., knowledge or understanding); such a goal may be only reached if all relevant beliefs of the epistemic agent are coherently systematized (BonJour, 1985, p. 28 f., 232 f.; for an explicit adoption with regard to MRE, see Elgin, 2014; Baumberger & Brun, 2021; see also Kauppinen & Hirvelä, 2022). Elgin, for example, argues that all commitments of an epistemic agent have some initial credibility and thus are a suitable basis for MRE:

“Our convictions form the basis for our actions. If projects grounded in a particular judgment often go awry, reservations develop and the courage of that conviction wanes. So confidence in a given judgment indicates that we have not yet found it an impediment to action. And that its acceptance has not obviously thwarted (and may even have advanced) our efforts is a reason to credit a judgment. […] At the outset of any inquiry then there is some epistemic presumption in favor of the commitments we already have.” (Elgin, 1996, p. 102).

Minimalistic foundationalism agrees that justifications via MRE require some basis, namely what the epistemic agent currently believes; however, it remains agnostic on the issue of whether the beliefs of the epistemic agent in fact have some initial credibility. That this is the case might be justified via MRE and thus be an element of a specific MRE account—a highly plausible element, in my view. However, this would be another contingent element of the method.

Depending on the context, foundationalism, whether minimalistic or not, is sometimes assumed to conflict with the fallibilism of MRE (see Sect. 5.2). However, using BonJour’s terminology, weak and even moderate foundationalists also see their basic beliefs (e.g., perceptual beliefs under favorable circumstances) as revisable or not immune to error. In this sense, fallibilism would be perfectly compatible with these sorts of foundationalism. Only strong foundationalism, in the spirit of Descartes for example, is incompatible.

Minimalistic foundationalism is a necessary element of MRE, since, without the restriction to the beliefs the epistemic agent currently holds and to the hypotheses and theories they deem relevant, it would be unclear how the plausibility of candidate systems can be evaluated in a rational manner (see Sect. 5.4).

5.2 Minimalistic fallibilism

The second rule concerns the kind of fallibilism that MRE implies. This can be articulated in the following form:

The epistemic agent should consistently treat all beliefs that enter the RE process or result from it as defeasible and revisable.

Fallibilism is therefore understood as primarily an epistemic stance. There are at least two interrelated reasons why we should understand it in this way:

-

1)

One might be tempted to state the fallibilism of MRE in a more substantial form. For example: “The epistemic agent should be wary that every belief may turn out to be wrong or incorrect and thus all beliefs should be regarded as revisable”. This, however, would presuppose that none of the beliefs is a necessary truth, since they could not, in principle, turn out to be wrong. MRE should not presuppose such a metaphysical (and rather dubious) claim a priori but offer the possibility of treating this matter neutrally via MRE. One might object that epistemic agents should not treat beliefs as revisable when they conceive them as necessary truths, so this possibility must be excluded if the rule applies to all beliefs. However, this is not correct: a belief that p is necessarily true, is not necessarily true itself. So, one might fail to identify necessary truths correctly, even if one’s belief in one can never turn out to be wrong. Thus, even if we identify a belief as necessarily true, we can reasonably treat it as a revisable belief.

-

2)

In general, we need to know why this rule is justified, if MRE is to be justified. However, such justification might be offered in different terms and there need not be a shared rationale for this fallibilism, therefore it is “minimalistic”. One feasible justification might be based on the claim that there is no belief whose truth or correctness is transparent to us, so that our justification for it is never conclusive (cf. Elgin, 1996; Hetherington, 2019). The adoption of one of the available justifications in turn would be a contingent element of a specific conception of MRE.

Minimalistic fallibilism is a necessary element of the method, since the justificatory process would otherwise not always involve balancing the strength of supporting and opposing arguments for the evaluation of rival epistemic positions. Such a process seems to be at the very heart of MRE. To see this, imagine that there are definitely fixed beliefs relevant to the specific inquiry. Conflicting beliefs (given that some principles of logic are accepted) would simply have to be adjusted and inferred beliefs would have to be accepted.

5.3 Moderate holism

Moderate holism, the third rule, actually consists of two rules which are closely connected to the ideal of an integrative inquiry that adequately takes into account the interrelations of beliefs. They can be stated as follows:

a) In the RE process epistemic agents have to consider all beliefs, theories and hypotheses—including their inferential relations—that they would deem relevant for the current inquiry after due reflection. They are relevant iff their inclusion would foreseeably alter the core result of the process. Considerations regarding work and time constraints can justify a deviation from the ideal of identifying all relevant beliefs, theories and hypotheses.

b) Conflicting beliefs, theories and hypotheses are not balanced against each other in isolation, but as part of possible systems of belief, which result from alternative plausible adjustments. These systems of belief—which are candidates for a RE state—are evaluated as a whole.

Moderate holism tries to explicate what it actually means for an epistemic agent to strive for a sufficiently wide RE. The demandingness of this task is not always acknowledged in the literature. To adequately aim for a RE, it is not enough to simply include some background theories. Rather, this requires the more demanding task of searching for every belief, theory and hypothesis that would make a difference, given certain time constraints.

Moderate holism is a necessary element of MRE for the following reasons: The search for a RE state presupposes the interconnectedness of the relevant beliefs, theories and hypotheses. Ignoring beliefs, theories and hypotheses (without further rationale) that one reflectively judges as relevant—at least prima facie—appears to be highly irrational. Moreover, without the requirements of moderate holism that correspond with the idea of wide RE, MRE would be too uncritical, as all proponents of MRE readily acknowledge.Footnote 19 However, if the holism were not moderate, which allows for deviation from the ideal in light of work and time constraints, this rule would only formulate an unfeasible ideal with which no epistemic agent could actually comply.

5.4 Minimalistic rationality

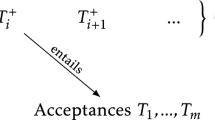

Finally, the rule of minimalistic rationality is concerned with evaluating within the RE process alternative and competing systems of belief that can be seen as relevant candidate systems for a RE. The rule thus provides a solution for the task of deciding between the alternative systems of belief that can be established by plausible adjustments of conflicting beliefs revealed by moderate holism. It provides the epistemic agent with a criterion that determines what system of beliefs can be accepted as RE and constitutes the core “mechanism” of MRE. Minimalistic rationality can be stated in the following manner:

Epistemic agents should choose the candidate system of beliefs which, as a whole, exhibits the highest plausibility—in light of all inferential relations and the strength of the agent’s beliefs. If the epistemic agents succeed in adjusting their beliefs accordingly, they have achieved a RE.

The name of the rule suggests—reasonably, as I maintain—that epistemic agents are in a very limited sense epistemically rational iff they succeed in believing—all things considered—what they themselves deem to be the most plausible.

One might object that this rule conflicts with a common picture of the RE process. Both Goodman and Rawls, for example, state that while pursuing a RE state we go back and forth between our beliefs and systematic principles or theories, sometimes adjusting a belief if it conflicts with a theory or principle we accept and sometimes adjusting a principle or theory if it conflicts with a belief we are unwilling to discard (Goodman, 1983, pp. 62–64; Rawls, 1999, p. 18; see also Brun, 2020; Beisbart et al., 2021; Rechnitzer, 2022a). This seems to imply a piecemeal approach to adjustment that contrasts with the practice implied by the rule of minimalistic rationality, where there is no adjustment before all things have been considered—adjustments only occur when the system of beliefs that is the most plausible in light of all inferential relations and the strength of the agent’s beliefs has been chosen. However, I propose that the reference to adjusting beliefs while “going back and forth” can be understood as a rather metaphorical characterization of the RE process. What Rawls and Goodman actually describe is a heuristic for widening our set of beliefs and considerations for the RE process —a heuristic that corresponds with the rule of moderate holism—and for assessing possible adjustments. By way of trial, we test the consequences of accepting plausible theories and other adjustments without actually committing to them—the adjustments are merely virtual. A reason for this heuristic is that epistemic agents often lack clarity about which beliefs, theories and hypotheses are relevant to the current inquiry, how they are inferentially interrelated, which of these beliefs, theories and hypotheses conflict and what strength they assign to their beliefs. By exploring possible adjustments, the epistemic agents achieve a better understanding of all these issues. An adjustment before all relevant issues have been considered (given time and work constraints) would be premature at best.

Another natural objection is that MRE is often characterized as a quest for the most coherent system of beliefs, but the rule of minimalistic rationality only refers to plausibility, not coherence. I contend that plausibility should be preferred over coherence for the following reasons: We might be tempted to think that the most coherent system of beliefs is just the same as the most plausible system of beliefs, at least when we consider all inferential relations between the beliefs. If so, plausibility and coherence are treated as synonymous in this context. If they are synonymous, it is sufficient to refer only to plausibility, of course. However, if they have different meanings, choosing between them as a criterion for evaluation might lead to different results of the respective RE processes. In this case, plausibility is better suited to figure in a definition of MRE. Despite the criticism that coherence is a vague concept (consistency plus x), there has been a considerable philosophical effort to specify it in formal epistemology with the result of several sophisticated coherence measures. However, all of these have been proven to be problematic (Olsson, 2021). Plausibility is not yet such a contaminated technical term. One might conceive it as the degree to which an epistemic agent deems a possible system of beliefs to be true or correct in in light of all inferential relations and the strength of the agent’s beliefs. A successful formal explication is certainly desirable at some point. However, as the term is invoked regularly when someone tries to rationally justify the acceptance of an account or position, it can be taken as a primitive notion for now.Footnote 20 In conclusion, if we have to choose between plausibility and coherence, especially in light of the available coherence measures (e.g., Shogenji, 1999), we should prefer the system of beliefs we find to be the most plausible all things considered. Why should we settle with a system we actually find on due reflection to be less plausible, although its degree of coherence might be higher?Footnote 21

Minimalistic rationality is a necessary element of MRE, since the adjustments in the RE process are not arbitrary but must follow a rational criterion. In proposing plausibility as this criterion, I deviate somewhat from the standard characterization of MRE, which refers instead to coherence. However, the systematic reasons for this deviation might be shared, and I think it offers a better reconstruction of the actual MRE practice.

6 A working definition of MRE

If we define MRE in terms of these four rules, this definition captures paradigmatic MRE conceptions, such as those proposed by Rawls (1999, 1974, 2001), Daniels (1996), DePaul (1993) or Elgin (1996, 2017). All these conceptions implicitly or explicitly include the four rules outlined here, at least according to some reasonable interpretation, and thus can be regarded as MRE conceptions according to our working definition.Footnote 22 They are MRE conceptions because they go beyond the conceptual core by arguing for additional contingent elements of the method via the most basic form of MRE. At least to my current understanding, no methodological approach to internal justification that one would reflectively judge to be an MRE approach is excluded. This test could show that at least one of our rules was falsely considered to be necessary.

The next question is, of course, if the four necessary rules are jointly also sufficient for MRE, so that an adequate working definition would be attainable.

If we define MRE in terms of these four rules, we exclude paradigmatic approaches to justification that one reflectively judges to be incompatible with MRE, such as the strong foundationalist transcendental argumentation offered by Wolfgang Kuhlmann in the tradition of Karl-Otto Apel (Kuhlmann, 2017). To my current understanding, no methodological approach to internal justification that one would reflectively judge to be not an MRE approach is included. This test could show that the rules were falsely considered to be jointly sufficient.

If the four necessary rules are jointly sufficient for MRE, we have achieved a working definition of MRE. And it is thus possible to answer the following questions: When do epistemic agents follow MRE? They follow MRE iff they respect the proposed elementary rules. When do epistemic agents achieve a RE? They achieve a RE iff they succeed in adjusting their beliefs according to the most plausible candidate system that emerged while following MRE.

Of course, I do not expect this working definition to be free of errors. On the contrary: There will emerge, hopefully, alternative working definitions and perhaps also criticisms of the proposed working definition that might lead to its refinement. It might also emerge that no definition of MRE can withstand reflective scrutiny after all.

7 Conclusion: deepening our understanding of the MRE

There is a need for a better understanding of the core mechanisms or rules of MRE. In light of this situation, I have argued that it is a reasonable endeavor to seek a working definition of MRE that focuses on the necessary and jointly sufficient elements of the method and thereby distinguishes them from contingent elements. I have proposed such a working definition. Epistemic agents follow MRE iff they follow four rules, which are stated here again synoptically:

-

I.

Minimalistic foundationalism:

Justification via MRE is tied to the epistemic agents’ own beliefs and evaluations. Epistemic agents may (only) include beliefs in the RE process that they in fact themselves happen to hold. They are also entitled to include hypotheses or theories they deem to be relevant or worth considering.

-

II.

Minimalistic fallibilism:

The epistemic agent should consistently treat all beliefs that enter the RE process or result from it as defeasible and revisable.

-

III.

Moderate holism:

a. In the RE process epistemic agents must consider all beliefs, theories and hypotheses—including their inferential relations—that they would deem to be relevant for the current inquiry after due reflection. They are relevant iff their inclusion would foreseeably alter the core result of the process. Considerations regarding work and time constraints can justify a deviation from the ideal of identifying all relevant beliefs, theories and hypotheses.

b. Conflicting beliefs, theories and hypotheses are not balanced against each other in isolation, but as part of possible systems of belief, which result from alternative plausible adjustments. These systems of belief—which are candidates for a RE state—are evaluated as a whole.

-

IV.

Minimalistic rationality:

Epistemic agents should choose the candidate system of beliefs which, as a whole, exhibits the highest plausibility—in light of all inferential relations and the strength of the agent’s beliefs. If the epistemic agents succeed in adjusting their beliefs accordingly, they have achieved a RE.

To my current knowledge, this is the first account to provide detailed necessary and jointly sufficient conditions for following MRE. One result of this approach is that one is able to adequately differentiate between necessary and contingent features of prominent MRE accounts. I gave two examples for contingent elements of MRE with Rawls’s considered judgement constraint and Daniels’s independence constraint in Sect. 4. A further example was introduced in Sect. 5.1 with Elgin’s weak foundationalism. All these contingent elements of MRE accounts must be justified by the more basic version of the method provided by the working definition. MRE, in its most basic form, can and should remain agnostic on these and other issues.

The working definition presented here differs from recent formal explications of MRE in the obvious aspect that the rules are stated informally. In this way, they can be referred to when one wants to answer the question whether a given formal model is an adequate representation of MRE. The corresponding review, of course, does not just work in one direction—a formal explication or model of MRE might also lead to revisions of the informal working definition via a RE process. Additionally, a comparison between the working definition and formal models is helpful in highlighting limitations or idealizations. As an example, here are two differences with respect to the formal model of MRE proposed and defended by Beisbart et al. (2021):

-

1)

The rule of holism and the corresponding search for relevant (new) beliefs, theories and hypotheses that one must incorporate is not included in this model yet, as far as I understand it. Of course, Beisbart, Betz and Brun require that the dialectical structure containing all relevant sentences with respect to the topic at issue be chosen appropriately. However, this is a task for persons working with the model and thus the quest for relevant beliefs, theories and hypotheses is arguably not a formal feature of the model itself. By employing the model, one assumes that the task has been done in an appropriate way: “[…] all relevant sentences are given from the beginning and do not change in the course of a RE process” (Beisbart et al., 2021, p. 444). According to the proposed working definition of MRE, however, the search for relevant beliefs, theories and hypotheses is included in the constitutive rules of the method, persists while one is pursuing RE via the method and only stops when a RE is, provisionally, attained. For actual epistemic agents employing MRE this is a crucial element of the method and matches with exemplary applications: Think of philosophers who are inquiring into a topic in moral philosophy and create a new thought experiment which uncovers beliefs that are relevant in the sense that they make a difference to the outcome of the method. They might do so if the newly found beliefs conflict with other beliefs, e.g., highly plausible systematic beliefs like “killing is worse than letting die” (see also Brun, 2018; Rechnitzer, 2022b, p. 272 f.). For a formal model, it is perfectly suitable to abstract from this element of MRE. However, this should be recognized as an idealization. Additionally, this is an interesting idealization, since it is at least not straightforwardly clear how the quest for relevant beliefs, theories and hypotheses can be formalized.

-

2)

There are theoretical virtues or desiderata (“account”, “systematicity”, and “faithfulness”), that feature prominently in the formal model. Together with further conditions, they jointly determine whether an epistemic state can be considered a RE (Beisbart et al., 2021, pp. 446–449). It is necessary to assign the desiderata specific weights, and this assignment is not part of the RE process of the model (Beisbart et al., 2021, p. 451 f., 454). However, according to the proposed working definition, these desiderata and their respective weights would be seen as relevant beliefs that the epistemic agents consider within the RE process (insofar as time restrictions allow for this). Interestingly, the evaluation of epistemic states by means of MRE according to the informal working definition might be included in a strategy that Beisbart, Betz and Brun discuss for setting the weights of the desiderata (Beisbart et al., 2021, p. 458).

As far as the informal working definition is justified in dealing with these aspects, these differences might suggest further refinements of the formal model or show its limits; alternatively, these differences might also inform a revision of the informal working definition.

The minimalistic rule-based analysis of MRE presented here is intended to be justified by means of MRE itself and is thus regarded as fallible and provisional. It is intended as a contribution to the ongoing task of a deeper understanding of MRE.

Notes

In the present paper I simply assume that there is such a thing as MRE. This is not an entirely trivial or innocent assumption. John Mikhail, for example, can be interpreted as asserting that there is merely the state of RE (Mikhail, 2011, p. 14, 2013, p. 204, however, see also 2011, p. 12, 2013, p. 289). However, many authors explicitly commit to MRE or criticize it, so the assumption is far from extraordinary. Moreover, since an explication of what is meant by MRE can also be helpful in assessing whether the notion of RE in fact implies or comes along with a corresponding method, it is a reasonable assumption for the present paper. I thank an anonymous reviewer for pressing me to clarify this issue.

The rule-based analysis of MRE I develop in this paper builds upon an earlier account that I first defended in Schmidt (2022). There have been important changes and refinements as well as considerable extensions.

See, for example, Rawls’s claim that MRE is “[…] is not peculiar to moral philosophy” (Rawls, 1999, p. 18).

What kind of states form the elements of a reflective equilibrium remains an open question. However, a minimal consensus is that MRE deals with doxastic states. For the remainder of this paper, I simply refer to the doxastic states of MRE as “beliefs” and thus suggest a rather non-technical and broad meaning of this word that encompasses these other doxastic states.

This might not seem a very informative point, since most philosophers today think that most judgements are revisable (Hetherington, 2019). However, MRE involves the stance that everything is revisable. I will come back to this issue in Sect. 5.2. Note that this does not preclude that some kinds of judgements can be discarded or prioritized for a specific area of inquiry if this is justified via RE.

If only a sufficiently wide systematization of our beliefs can be a RE, “narrow RE” would be an oxymoron.

Typical descriptions of wide RE contain more specific conditions for widening narrow RE, e.g., by using background theories (e.g., Knight, 2023, Sect. 2.2), but for my minimalistic working definition of RE it is advantageous to leave open how exactly the widening is done.

Indeed, Goodman’s account of MRE is especially valuable since he presents it in a context—justification in the discipline of logic—that is sometimes regarded as outside of the scope of MRE. This is important for proponents of the method’s universal applicability.

If there are some elements which are not formalizable, the informal account of RE would be more basic and thus have priority (see Schmidt, 2022, 366–370).

At some points Walden does offer some positive characterization of the method. For example: “[…] any defender of the method of reflective equilibrium worth his salt will insist that we include any considerations potentially relevant to the questions we are trying to answer, or at least those we have access to.” (Walden, 2013, p. 246, see also p. 251).

Kauppinen and Hirvelä identify up to 1024 variants or conceptions of MRE that might result with regard to “possible elements” of the method. Thus, their account is closely related to the distinction between necessary and contingent elements of MRE that I advocate here (Kauppinen & Hirvelä, 2022).

An extended discussion of points raised in this paragraph can be found in several sections in Schmidt (2022), 345–351, 377–380, 380–383).

It might also be possible to justify what one should believe on moral grounds where this is counter to epistemic grounds. However, how do we know if morality actually requires that we should believe something? I hold that, to answer this question, one must rely on an epistemic justification via MRE.

I thank the editors for making me aware of this possible objection to my MRE account.

The position by Holmgren (1989) might be seen as an exception, but it is possible to interpret the account of narrow RE she argues for as an account of wide RE.

I thank an anonymous reviewer for this suggestion.

Of course, even in this case MRE could be called a “coherence method” if this refers to the structure of justification (circular vs. foundational).

Detailed interpretations of the MRE accounts of Rawls, Daniels, DePaul, and Elgin can be found in Schmidt (2022, 23–152, 158–223, 223–278, 281–318).

References

Baumberger, C., & Brun, G. (2021). Reflective equilibrium and understanding. Synthese, 198(8), 7923–7947. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-020-02556-9

Beisbart, C., Betz, G., & Brun, G. (2021). Making reflective equilibrium precise: A formal model. Ergo, 8(0). https://doi.org/10.3998/ergo.1152. Article 0.

BonJour, L. (1985). The structure of empirical knowledge. Harvard University Press.

Botti, D. (2019). John Rawls and American pragmatism: Between engagement and avoidance. Lexington Books.

Brandt, R. B. (1979). A theory of the good and the right. Oxford University Press.

Brun, G. (2016). Explication as a method of conceptual re-engineering. Erkenntnis, 81(6), 1211–1241. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10670-015-9791-5

Brun, G. (2018). Thought experiments in Ethics. In M. T. Stuart, Y. J. H. Fehige, & J. R. Brown (Eds.), The Routledge companion to thought experiments (pp. 195–210). Routledge.

Brun, G. (2020). Conceptual re-engineering: From explication to reflective equilibrium. Synthese, 197(3), 925–954. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-017-1596-4

Brun, G. (2022). Re-engineering contested concepts. A reflective-equilibrium approach. Synthese, 200(2), 168. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-022-03556-7

Daniels, N. (1979). Wide reflective equilibrium and theory acceptance in ethics. The Journal of Philosophy, 76(5), 256. https://doi.org/10.2307/2025881

Daniels, N. (1980). Reflective equilibrium and archimedean points. Canadian Journal of Philosophy, 10(1), 83–103.

Daniels, N. (1996). Justice and justification: Reflective equilibrium in theory and practice. Cambridge University Press.

Daniels, N. (2020). Reflective equilibrium. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), The Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy (Summer 2020). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2020/entries/reflective-equilibrium/

DePaul, M. R. (1993). Balance and refinement beyond coherence methods of moral inquiry. Routledge.

Elgin, C. Z. (1996). Considered judgment. Princeton University Press.

Elgin, C. Z. (2014). Non-foundationalist epistemology: Holism, coherence, and tenability. In M. Steup (Ed.), Contemporary debates in epistemology (2nd ed., pp. 244–255). Wiley Blackwell.

Elgin, C. Z. (2017). True enough. The MIT.

Freivogel, A. (2021). Modelling reflective equilibrium with belief revision theory. In M. Blicha & I. Sedlár (Eds.), The logica yearbook 2020 (pp. 65–80).

Gališanka, A. (2019). John Rawls: The path to a theory of justice. Harvard University Press.

Goodman, N. (1983). Fact, fiction, and forecast (4th ed.). Harvard University Press.

Hetherington, S. (2019). Fallibilism. The internet encyclopedia of philosophy. https://iep.utm.edu/fallibil/

Holmgren, M. (1989). The wide and narrow of reflective equilibrium. Canadian Journal of Philosophy, 19(1), 43–60.

Kauppinen, A., & Hirvelä, J. (2022). Reflective equilibrium. In D. Copp, T. Rulli, & C. Rosati (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of normative ethics. Oxford University Press. https://philarchive.org/versions/ANTRE-4

Kelly, T., & McGrath, S. (2010). Is reflective equilibrium enough? Philosophical Perspectives, 24(1), 325–359. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1520-8583.2010.00195.x

Knight, C. (2023). Reflective equilibrium. In E. N. Zalta & U. Nodelman (Eds.), The Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy (Winter 2023). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2023/entries/reflective-equilibrium/

Kuhlmann, W. (2017). Transcendental-pragmatic foundation of ethics. Transcendental arguments and ethics. In M. H. Werner, R. Stern, & J. P. Brune (Eds.), Transcendental arguments in moral theory (pp. 247–264). De Gruyter.

Mandle, J. (2016). The Choice from the Original Position. In J. Mandle & D. A. Reidy (Eds.), A companion to Rawls (Paperback edition, pp. 128–143). Wiley Blackwell.

Meylan, A. (2017). The pluralism of justification. In A. Coliva & N. Jang Lee Linding Pedersen (Eds.), Epistemic pluralism (pp. 129–143). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-65460-7_5

Mikhail, J. (2011). Rawls’ concept of reflective equilibrium and its original function in a theory of justice. Washington University Jurisprudence Review, 3(1), 1–30.

Mikhail, J. (2013). Elements of moral cognition: Rawls’s linguistic analogy and the cognitive science of moral and legal judgment (1. paperback ed). Cambridge Univ. Press.

Olsson, E. (2021). Coherentist theories of epistemic justification. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), The Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy (Fall 2021). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2021/entries/justep-coherence/

Rawls, J. (1950). A study in the grounds of moral knowledge: Considered with reference to the moral worth of character [PhD Thesis]. Princeton University.

Rawls, J. (1951). Outline of a decision procedure for ethics. The Philosophical Review, 60(2), 177–197. https://doi.org/10.2307/2181696

Rawls, J. (1971). A theory of justice. Belknap.

Rawls, J. (1974). The independence of moral theory. Proceedings and Addresses of the American Philosophical Association, 48, 5. https://doi.org/10.2307/3129858

Rawls, J. (1995). Political liberalism: Reply to habermas. The Journal of Philosophy, 92(3), 132. https://doi.org/10.2307/2940843

Rawls, J. (1999). A theory of justice: Revised edition. Belknap.

Rawls, J. (2001). In E. Kelly (Ed.), Justice as fairness: A restatement. Harvard University Press.

Rawls, J. (2005). Political liberalism: Expanded edition. Columbia University. Columbia Classics in Philosophy edition.

Rechnitzer, T. (2022a). Applying reflective equilibrium: Towards the justification of a precautionary principle (Vol. 27). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-04333-8

Rechnitzer, T. (2022b). Turning the trolley with reflective equilibrium. Synthese, 200(4), 272. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-022-03762-3

Rechnitzer, T., & Schmidt, M. W. (2022). Reflective equilibrium is enough. Against the need for pre-selecting considered judgments. Ethics Politics & Society, 5(2). https://doi.org/10.21814/eps.5.2.210. Article 2.

Reidy, D. A. (2016). From philosophical theology to democratic theory: Early postcards from an intellectual journey. In J. Mandle, & D. A. Reidy (Eds.), A companion to rawls (pp. 9–30). Wiley Blackwell. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2400118

Scanlon, T. M. (2002). Rawls on justification. In S. Freeman (Ed.), The Cambridge companion to rawls (1st ed., pp. 139–167). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CCOL0521651670.004

Schmidt, M. W. (2022). Das Überlegungsgleichgewicht als lebensform: Versuch zu Einem Vertieften Verständnis Der Durch John Rawls bekannt gewordenen rechtfertigungsmethode. Brill.

Shogenji, T. (1999). Is coherence truth conducive? Analysis, 59(264), 338–345. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8284.00191

Singer, P. (1974). Sidgwick and reflective equilibirum. The Monist, 58(3), 490–517.

Slavny, A., Spiekermann, K., Lawford-Smith, H., & Axelsen, D. V. (2020). Directed reflective equilibrium: Thought experiments and how to use them. Journal of Moral Philosophy, 1(aop), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1163/17455243_20203008

Thagard, P. (2000). Coherence in thought and action. MIT Press.

Walden, K. (2013). In defense of reflective equilibrium. Philosophical Studies, 166(2), 243–256. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-012-0025-2

Welch, J. R. (2014). Moral strata. Springer.

White, M. (1999). A philosopher’s story. Pennsylvania State University Press.

Acknowledgements

First, I would like to thank Richard Lohse and Viktor Schubert who both did not only comment on multiple versions of the manuscript but also provided me with deep discussions on the corresponding topics. Next, I would like to thank Eike Düvel, Jakob Ohlhorst, and Wolf Rogowski who helped with their detailed comments to improve the text considerably. Furthermore, I had the opportunity to present some version of the manuscript to my research group Philosophy of Engineering, Technology Assessment, and Science at the Institute for Technology Assessment and Systems Analysis (ITAS) at the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT) and at the 11th conference of the German Society for Analytic Philosophy (GAP.11) in Berlin; I benefitted much from the exchange with the audiences. I am grateful to have had two critical but also very helpful anonymous reviewers. Finally, a special thanks to the editors – Claus Beisbart, Georg Brun and Gregor Betz – who went at great length to improve my MRE account with their critical questions and suggestions.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author has no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Schmidt, M.W. Defining the method of reflective equilibrium. Synthese 203, 170 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-024-04571-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-024-04571-6