Abstract

I argue that there is tension in Wittgenstein’s position on trivialities (i.e. tautologies and contradictions) in the Tractatus, as it contains the following claims: (A) sentences are pictures; (B) trivialties are not pictures; (C) trivialities are sentences. A and B follow from the “picture theory” of language which Wittgenstein proposes, while C contradicts it. I discuss a way to resolve this tension in light of Logicality, a hypothesis recently developed in linguistic research. Logicality states that trivialities are excluded by the grammar, and that under the right analysis sentences which look trivial are in fact contingent. The tools necessary to support Logicality, I submit, were not available to Wittgenstein at the time, which explains his commitment to C. I end the paper by commenting on some points of contact between analytic philosophy and the generative enterprise in linguistics which are brought into relief by the discussion.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 The picture theory of language

Wittgenstein (1921), commonly known as Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus,Footnote 1 purports to have found the conclusive solution to all philosophical problems (“die Probleme endgültig gelöst zu haben”). This solution consists in showing that there are really no problems, or more precisely, that the formulation of these problems (“die Fragestellung dieser Probleme”) will be recognized as gibberish, once the logic of our language (“die Logik unserer Sprache”) is understood.

The main contribution of the Tractatus, in my opinion, is the thesis that “the logic of our language” is to be identified with what has traditionally been called “grammar”. Grammar, in the classic sense, is what distinguishes between sentences and non-sentences.Footnote 2 It defines what a sentence is, thereby delineating what can be expressed as either true or false. This is precisely Wittgenstein’s stated objective in the Tractatus. “The book [...] aims to draw a limit [...] to the expression of thoughts,” he says in the preface. This limit, as he subsequently clarifies, will be drawn “in language”, and will serve to separate the intelligible from “nonsense”.Footnote 3

But what does identifying logic with grammar amount to exactly? To repeat: grammar distinguishes between sentences and non-sentences. It accounts for the fact that (1a) is a sentence but (1b) is not, for example.

Logic, on the other hand, is what distinguishes between valid and invalid arguments. It accounts for the fact, for example, that the inference in (2a) is justified but the inference in (2b) is not.

The suprising claim made by Wittgenstein in the Tractatus is that the phenomenon exemplified by (1) and the phenomenon exemplified by (2) should receive a unified explanation. Specifically, the contrast with respect to sentencehood and the contrast with respect to validity should be accounted for by one and the same theory. This theory will tell us what a sentence is and, in addition, will tell us, for any sentence \(\phi \), what other sentences are true if \(\phi \) is true. Last but certainly not least, it will also dissolve all philosophical problems.

The theory in question is known as the “picture theory of language” (Keyt, 1964), henceforth PTL. The essence of PTL is presented in 4.01: “A sentence is a picture of reality”.Footnote 4 Sentences, Wittgenstein maintains, are pictorial. They represent states of affairs in the same way as, say, the score of Schubert’s Unvollendete represents the sound of this symphony: “A gramophone record, the musical thought, the musical notation, the sound waves, all stand to one another in that internal relation of depicting that holds between language and world” (4.014). The structure of a sentence, then, is isomorphic to the structure of the state of affairs it describes (Daitz, 1953): “The configuration of simple signs in a propositional sign corresponds to the configuration of objects in a state of affairs” (3.21). To see how PTL accounts for both sentencehood and validity, we will discuss an example.Footnote 5

Suppose the linguistically relevant reality has three basic elements, i.e. three “objects” (“Gegenstände”): (i) John, (ii) Mary, and (iii) the property of smoking.Footnote 6 Logical space would then contain four possible worlds: one where both John and Mary smoke, one where only John smokes, one where only Mary smokes, and one where neither of them smokes. Let us now consider two languages. The first is familiar: John is symbolized as j, Mary as m, smoking as s, that John smokes as s(j), that Mary doesn’t smoke as \(\lnot s(m)\), that John smokes but Mary doesn’t as \(s(j) \wedge \lnot s(m)\), etc. We will call this language L\(_\text {F}\), with the subscript “F” being mnemonic for ‘Fregean’. The second language, call it L\(_\text {W}\), will be the one which approaches more closely the “pictorial” ideal envisioned by Wittgenstein. In L\(_\text {W}\), John is symbolized as a pebble , Mary as a marble , and smoking as a jar . The fact that an individual smokes or does not smoke will be represented by placing the symbol for that individual inside or outside of the symbol for smoking, respectively. We now compare some sentences in the two languages as to the correspondence between them and the states of affairs they describe.Footnote 7

Let us ask in what sense L\(_\text {W}\) is “pictorial”, i.e. “isomorphic” to reality, but L\(_\text {F}\) is not. First, note that a necessary condition for the isomorphism between two structures is that they have the same number of primitive elements. This condition is satisfied by L\(_\text {W}\) but not L\(_\text {F}\). The reality to be represented has three objects: John, Mary, and smoking. L\(_\text {W}\) has three basic symbols, i.e. names: the pebble, the marble, and the jar. This is not the case for L\(_\text {F}\), which has seven names: j, m, s, (, ), \(\lnot \), and \(\wedge \). Sentences of L\(_\text {W}\) contain nothing but names hanging in one another “like the links of a chain” (2.03), i.e. by virtue of their form alone, just as in the represented states of affairs objects hang in one another without any kind of “logical frame” into which they fit (Hintikka, 1994). Sentences of L\(_\text {F}\), on the other hand, contain not only names but also “syncategorematic glue” (i.e. the brackets and the connectives) which holds them together. There is another sense in which L\(_\text {W}\) is more pictorial than L\(_\text {F}\). Consider the shape of the names. In L\(_\text {F}\), the name for smoking is s, a letter, just like the names for John (j) and Mary (m). In L\(_\text {W}\), it is the jar, which differs from the pebble and the marble in that it is a container which allows the distinction to be made between things that are inside and things that are outside of it. The property of smoking, by nature, distinguishes between smokers and non-smokers. There is thus a higher degree of verisimilitude, in the relevant sense, between smoking and the jar than between smoking and the letter s.Footnote 8

This last point about the shapes of names brings us to the issue of sentencehood. The claim, to repeat, is that PTL accounts for sentencehood: it includes sentences and excludes non-sentences. Let us start by considering what would be non-sentences in L\(_\text {F}\): j(s), s(s), m(j), etc. How are these excluded? Obviously, the shape of the symbols themselves would not do the job: writing s(j) is just as easy as writing j(s). What would be required is an extrinsic theory of syntax which (i) categorizes the basic symbols into different “parts of speech”, i.e. “types”, and then (ii) imposes rules of combination upon these types. For example, it would say that s is an adjective, j is a noun, and if \(\alpha \) is an adjective and \(\beta \) is a noun then \(\alpha (\beta )\) is a sentence but \(\beta (\alpha )\) is not a sentence, etc.Footnote 9 Let us now turn to L\(_\text {W}\). What would be the L\(_\text {W}\) counterpart of the non-sentence j(s)? Well, it would be the jar placed inside the pebble. But we cannot place the jar inside the pebble: the forms of these symbols do not allow such a configuration. Thus, the pictorial counterpart of j(s) is ineffable.Footnote 10 The same holds for the pictorial counterparts of s(s) and m(j): there is no way to place the jar inside of itself or the pebble inside of the marble. As we can see, there is no need for an extrinsic theory of syntax. The shapes of the symbols themselves determine which combinations are possible and which ones are not, thereby distinguishing between sentences and non-sentences. Grammar, thus, emerges from the pictorial nature of representation: PTL accounts for sentencehood.

How does PTL account for validity? Again, we first consider L\(_\text {F}\). What guarantees, for instance, that L\(_\text {F}\)-3 entails L\(_\text {F}\)-1 but not vice versa? Obviously, it cannot be the shape of the expressions themselves. The logic of L\(_\text {F}\), just like its syntax, has to be imposed extrinsically by way of a theory which tells us that the inference in (4a) is valid but the inference in (4b) is not.Footnote 11

Let us now ask a parallel question for L\(_\text {W}\): what guarantees that L\(_\text {W}\)-3 entails L\(_\text {W}\)-1 but not vice versa? The answer seems to be that the question itself is ridiculous. I can see, with my own eyes, that the pebble is inside of the jar in L\(_\text {W}\)-3. There is no way for me not to see the pebble inside the jar when I see the pebble inside and the marble outside the jar. In other words, I cannot conceive of the possibility that L\(_\text {W}\)-3 is true while L\(_\text {W}\)-1 is false, simply because I see L\(_\text {W}\)-1 in L\(_\text {W}\)-3. What about the fact that L\(_\text {W}\)-1 does not entail L\(_\text {W}\)-3? Well, this fact is also obvious: looking at L\(_\text {W}\)-1, I do not see the marble, which means I do not see the marble outside the jar, which means I do not see both the pebble inside the jar and the marble outside the jar. In other words, I do not see L\(_\text {W}\)-3 in L\(_\text {W}\)-1.Footnote 12 If we had to posit “rules” which allow the inference from L\(_\text {W}\)-3 to L\(_\text {W}\)-1 but disallow the inference in the opposite direction, they would say something banal and empty like “Look!” or “Think!” Thus, rules of inference are “superfluous” for L\(_\text {W}\) (5.132). “That the truth of one proposition follows from the truth of other propositions can be seen from the structure of the propositions” (5.13). Therefore, logic “take[s] care of itself” (5.473) (cf. McGinn, 2006). Logic, as it were, emerges from the pictorial nature of representation: PTL accounts for validity.

Finally, how does PTL dissolve all philosophical problems? Here is Wittgenstein’s reasoning, as I see it. First, a “problem” exists only to the extent that it can be formulated. How is a problem formulated? By asking whether a sentence is true, which means, given PTL, asking whether a picture corresponds to reality. But pictures are empirical: we can only know whether they are true by observation (2.224, 2.225). This means that every problem can in principle be settled by observation, which is to say by natural science. Philosophy, however, “is not one of the natural sciences” (4.111). It then follows that there are no problems for philosophy to solve.

My main aim in the preceding paragraphs has been to argue that Wittgenstein’s picture theory of language (PTL) serves the double function of (i) distinguishing between sentences and non-sentences and (ii) distinguishing between valid and invalid arguments. I will now turn to a discussion on sentences that are either a contradiction or a tautology. Following a practice common in the linguistic literature, I will call these sentences “trivialities”. This, I should note, is not a term Wittgenstein uses in the Tractatus. My use of it is purely to reduce the number of words on the page: instead of saying “contradictions and tautologies” every time, I say “trivialities”.

Let us start, again, with L\(_\text {F}\). Take \(s(j) \wedge \lnot s(j)\), for example. This is a contradiction. It is, of course, a sentence of L\(_\text {F}\), given that the syntax of L\(_\text {F}\) should (i) include s(j) as a sentence, (ii) allow any sentence to be negated, and (iii) allow any two sentences to be conjoined.Footnote 13 It follows, then, that the negation of \(s(j) \wedge \lnot s(j)\), i.e. \(\lnot (s(j) \wedge \lnot s(j))\), a tautology, is also a sentence.Footnote 14 Thus, trivialities are sentences of L\(_\text {F}\). Now let us ask what the L\(_\text {W}\) counterpart of \(s(j) \wedge \lnot s(j)\) would be. Presumably, it would be a configuration in which the pebble is inside as well as outside of the jar. This configuration, of course, is ineffable. Thus, contradictions in L\(_\text {F}\) have no “translation” in L\(_\text {W}\). The shapes of the symbols in L\(_\text {W}\) just do not allow such arrangements. What about tautologies, which are the negation of contradictions? Do they have L\(_\text {W}\) translations? I propose that the answer is no. Note that tautologies are the negation of contradictions. Let us make the conjecture in (5).

I will now make a brief excursus on NC. First, I emphasize that it is a conjecture. At this point, I do not have a general account of how negation works for such a pictorial language as L\(_\text {W}\). The cases we have considered are simple: \(\lnot S(m)\) is represented by placing the marble outside of the jar, for example. But how do we represent \(\lnot (S(j) \wedge \lnot S(m))\)? I do not have an answer. It is intuitively clear how conjunction is represented pictorially. But that is not the case for negation. And it is not clear to me, from what Wittgenstein says in the Tractatus, whether he has a cogent and general proposal with respect to pictorial negation. Hintikka (2000) and Eisenthal (2023) sketch some ideas which are, in my opinion, quite vague, and to the extent that I can make out what these authors say, I do not see how they would represent \(\lnot (S(j) \wedge \lnot S(m))\). Note that once we figure out how negation works pictorially, we will also have disjunction and implication, as these functions are definable in terms of negation and conjunction. For present purposes, I will assume NC, and leave the task of deriving this conjecture, either from Wittgenstein’s text or from elaborations of it, to future work. My hope is that the readers will not find NC so implausible as to stop reading.Footnote 15 This is the end of the excursus.

Let us now come back to the main discussion. Given NC and the fact that contradictions are ineffable in L\(_\text {W}\), it follows that tautologies are also ineffable in L\(_\text {W}\). Thus, L\(_\text {W}\) excludes contradictions as well as tautologies, i.e. it excludes trivialities, from the set of sentences. This fact, of course, lies in the nature of pictures. A picture, as was mentioned above, is empirical: it has to match some state of affairs and fail to match some other. Thus, it cannot be trivial. Just as we cannot use musical notation to produce a score which matches every or no possible piece of music, we cannot use linguistic signs to construct a model of every or no possible state of affairs. At various places in the Tractatus, Wittgenstein seems to concede that trivialities are non-sentences. “Tautology and contradiction are not pictures of reality”, he admits in 4.462. It should then follow that they are non-sentences, since sentences, by hypothesis, are pictures of reality. “[P]ropositions that are true for every state of affairs cannot be combinations of signs at all”, Wittgenstein says in 4.466. And because they are not combinations of signs, their negations are not either: “Tautology and contradiction are the limiting cases of the combination of symbols, namely, their dissolution” (4.466). But Wittgenstein, curiously, stops short of considering trivialities non-sentences. He calls non-sentences, i.e. arrangement of signs that are excluded by logical syntax, “nonsensical” (“unsinnig”). For example, John likes and Socrates is identical would be nonsensical, because in both cases a transitive predicate is lacking its direct object, incurring a violation of what linguists call the \(\Theta \)-Criterion.Footnote 16 However, Wittgenstein insists that that is not the case with trivialities. He declares, explicitly, that “tautology and contradiction are [...] not nonsensical”, and confirms that they are “part of the symbolism” (4.4611). Thus, he takes trivialities to be sentences. This is baffling: given the theory Wittgenstein proposes (PTL), he should exclude trivialities from the symbolism, i.e. should consider them nonsensical, but he does not. It should be noted, nevertheless, that Wittgenstein does end up describing trivialities using a word which is very close to “nonsensical”. The word is “senseless” (“sinnlos”). “Tautology and contradiction are senseless”, he says in 4.461. Thus, non-sensicality and senselessness both implies non-interpretability, but only non-sensicality implies non-sentencehood (von Wright, 2006; Biletzki & Matar, 2021; Proops, to appear). The morphological and semantic similarity between “senseless” and “non-sensical”, I think, is not accidental. It suggests that Wittgenstein finds trivialities to be “almost” non-sentences. One might say he thinks they should be non-sentences but refrain from going as far as saying they actually are.

The question that arises at this point is whether there is inconsistency in Wittgenstein’s theory of language. I will consider, first, the negative answer. Suppose we say there is no inconsistency. The challenge we face would then be to make sense of the fact that Wittgenstein says

How would we do that? Well, let us claim that A has existential, not universal, quantificational force. Specifically, the word “sentences” in A means ‘some sentences’, not ‘all sentences’.Footnote 17 Under this reading, A is compatible with B and C. This account, of course, requires us to say that PTL does not apply generally to all sentences. We need to exclude trivialities from its domain. One way to do that is to say that PTL applies only to what Wittgenstein calls “sinnvolle Sätze” (meaningful sentences). Trivialities are “sinnlos”, hence are not in the domain of PTL. Another way to exclude trivialities from PTL is to restrict PTL to atomic sentences. Trivialities cannot be atomic, since they involve at least one sentence and its negation, so they will not be in the domain of PTL. Restricting the domain of PTL, therefore, is a strategy to save Wittgenstein from inconsistency. It is not my aim, in this paper, to provide a conclusive argument for or against this strategy. I would just note here that I do not think it squares well with the text. Consider Wittgenstein’s use of the phrase “sinnvoller Satz”, for example. It is quite clear from the text that the adjective “sinnvoll” is not pleonastic: it restricts the set of sentences to a proper subset.Footnote 18 But this fact strongly suggests that Wittgenstein’s use of “Satz” is not restricted. In other words, it suggests that the null hypothesis is correct: when Wittgenstein says “Satz”, he means ‘Satz’, and when he says “sinnvoller Satz”, he means ‘sinnvoller Satz’. Consequently, when he says “[d]er Satz is ein Bild der Wirklichkeit” (“sentences are pictures of realities”), he is not talking about a specific subset of sentences, but about sentences tout court.Footnote 19 In fact, Eisenthal (2023) has argued, quite convincingly in my opinion, that there is textual evidence from both the Tractatus and Wittgenstein’s Notebooks (Wittgenstein, 1989) that “Wittgenstein consistently treated the picture theory as applying to all propositions” (Eisenthal, 2023, p. 165), and that “in many of Wittgenstein’s canonical statements to the effect that propositions are pictures, the claim is put forward in complete generality” (Eisenthal, 2023, p. 167).

Thus, while I acknowledge, and do not rule out, the possibility of making sense of A, B and C by interpreting A as an existential statement, i.e. by restricting the domain of PTL, I would like to explore an alternative. This alternative does not ask how A can be interpreted so that Wittgenstein’s theory is consistent, but accepts that the theory is inconsistent and asks why Wittgenstein commits to C. Note, first, that A and B are not inconsistent: they both follow from PTL. It is C in conjunction with A and B that causes a problem. Second, note that I am not claiming Wittgenstein is unaware of the inconsistency. I believe he is. He proposes a theory of language which is, in a way, overwhelmingly intuitive: symbols stand for objects, and configurations of symbols stand for configurations of objects. This is A. It is also overwhelmingly intuitive that such pictorial representations cannot be a priori true or a priori false, i.e. cannot be trivial. Wittgenstein realizes this, and stresses it in the text (2.225). This is B. The consequence of A and B is clearly that trivialities is not part of the language, because they cannot be pictured. Wittgenstein, however, says they are part of the language. This is C. Is he aware that C conflicts with A and B? I think he is, and I think that is why he calls trivialities “sinnlos”. Thus, they are sentences that are “defective” in some sense. One can say: they are halfway between “sinnvoll” and “unsinnig”. But this move by Wittgenstein, in my view, does not solve the problem. Grammar specifies a set of sentences. Something is either in the set or not. Saying that trivialities are in the set but defective does not resolve the conflict between A and B on the one hand, which together entail trivialities are not in the set, and C on the other, which says they are. Thus, what I am saying is not that Wittgenstein is unaware of the inconsistency in his theory, but that he tries but in the end fails to resolve it.Footnote 20

Let us now ask why Wittgenstein commits to C, which contradicts the theory he proposes. The reason, in my view, has a phenomenological component as well as a logical one. On the one hand, Wittgenstein experiences such expressions as (6a) and (6b) as sentences of the language, i.e. as structures which can be built using the rules of the grammar.

One the other hand, he interprets them as trivialities: he analyzes (6a) as \(\phi \wedge \lnot \phi \), a contradiction, and (6b) as \(\phi \vee \lnot \phi \), a tautology. The experience and the interpretation, together, lead to Wittgenstein’s conclusion that trivialities are sentences, which is inconsistent with the rest of his theory. Restoring consistency to Wittgenstein’s position, then, requires contesting this conclusion, which means either contesting the experience or contesting the interpretation. There is, of course, no point in the first course of action: visceral experiences such as those pertaining to sentencehood are basic facts from which we start. It is left, then, to question Wittgenstein’s analysis of (6a) and (6b). I will now turn to the discussion of a hypothesis about natural language which says that this analysis is incorrect. More specifically, it says that (6a) and (6b) are perceived as sentences precisely because they are not trivial.

2 Logicality

The hypothesis in question goes by the name of “Logicality”. Logicality states that universal grammar interfaces with a natural deductive system and filters out sentences expressing tautologies or contradictions (Chierchia, 2006; Del Pinal, 2019, 2022). In other words, Logicality claims that trivialities are ill-formed. I will present this intriguing thesis by discussing two cases, one illustrating the ill-formedness of contradictions, the other that of tautologies. Both pertain to the distribution of quantifiers, exemplified by universal every and existential a.

Before I proceed, a terminological clarification is in order. In section 1, I said grammar distinguishes between “sentences” and “non-sentences”. From now on I will speak of this distinction as one between “well-formed sentences” and “ill-formed sentences”, or equivalently, between “grammatical sentences” and “ungrammatical sentences”. Thus, the notion of sentencehood will be verbalized as one of “well-formedness” or “grammaticality”. Nothing of substance hinges on this change of labels, which is made just to bring our discussion closer to how linguists talk. The fact remains that some but not all arrangements of symbols are part of the language and grammar separates those that are (“sentences”, “well-formed sentences”, “grammatical sentences”) from those that are not (“non-sentences”, “ill-formed sentences”, “ungrammatical sentences”).Footnote 21

Let us start by considering the contrast in (7). Following standard practice, I will mark ill-formedness with #.

A fact about exceptive constructions, i.e. sentences of the form D(P except E)(Q), is that they are well-formed only if D, the determiner, is universal.Footnote 22 When D is existential, ill-formedness results.

This fact suggests that interpretation can be relevant for grammaticality. I will assume the standard semantics of quantifiers according to which they express relations between two sets. For every the relation is ‘is a subset of’, and for a, ‘has a non-empty intersection with’ (Barwise & Cooper, 1981; Heim & Kratzer, 1998).Footnote 23

Our intuition about (7a) is that it is a normal sentence, i.e. something that could be said and understood. On the other hand, we feel that (7b) is just gibberish: it sounds weird, and we don’t really know what it means. The most well-known account of the contrast is one proposed by von Fintel (1993). What is interesting about this account, and pertinent to our discussion, is that it explains the ill-formedness of (7b) as resulting from this sentence being contradictory. Specifically, von Fintel assigns to exceptive constructions the semantics in (9), where X−Y is the complement of Y in X, i.e. the set of things in X that are not in Y.

This analysis accomplishes two things at once. First, it captures the right meaning of (7a). Second, it determines (7a) to be contingent and (7b) to be trivial, thereby making a crucial distinction between the well-formed and the ill-formed sentence. Let us see how. Consider (7a) first. Given (9), this sentence is predicted to have the following truth condition.Footnote 24

Together, (10a) and (10b) means that (i) John is a student, (ii) John did not come, and (iii) every other student came, as the reader is invited to verify for herself. This is precisely the truth condition which we intuitively associate with (7a). It is, of course, contingent: we get truth if John is the only student who did not come and falsehood otherwise. Note that C in (10b) ranges over all sets including \(\emptyset \). As X\(-\) \(\emptyset \) \(=\) X, we predict (11) to be an entailment of (10b), hence an entailment of (7a).

Now let us apply (9) to (7b). The truth condition we get for this sentence is (12).

This condition, as it turns out, is trivial. Recall, again, that C can be \(\emptyset \). Thus, we predict (13) to be an entailment of (12b), hence an entailment of (7b).

Obviously, (13) is contradictory: its first conjunct entails that a student came while its second conjunct says that this is not the case. This fact is considered by von Fintel to be responsible for the ill-formedness of (7b).Footnote 25

Let us now turn to an example which illustrates ill-formedness of a sentence due to its being a tautology. Consider the contrast between the two existential sentences in (14).Footnote 26

Again, we see two sentences which are identical with respect to syntactic category and constituency: they are both of the form there(D(P)).Footnote 27 What distinguishes them is the semantics of D: existential in (14a), universal in (14b). This case, then, is also one where interpretation seems to affect grammaticality, as the difference between (14a) and (14b) feels like that between a well-formed and an ill-formed sentence. The standard account for (14) is Barwise and Cooper (1981). What it amounts to, basically, is that the word there says that its argument is true of the universe of discourse U, i.e. the set of all entities. This semantics is given in (15). The truth condition predicted for (14a) and (14b) are spelled out in (15a) and (15b), respectively.Footnote 28

What (15a) says is that the set of flies in my soup is not empty. This condition, of course, is not trivial. It is met in case there is at least one fly in my soup and not met otherwise. What (15b) says, on the other hand, is trivial: since U is the set of everything, it is a superset of the set of flies in my soup, whether or not the latter is empty (given that \(\emptyset \) is a subset of every set). It is this semantic difference between (14a) and (14b) which Barwise and Cooper (1981) take to be responsible for the grammatical contrast between these sentences.

The two cases we have just examined, (7) and (14), illutrate the claim that the language system interacts with logic. More specifically, it corroborates Logicality, which states that trivialites are filtered out as ill-formed. The cases pertain to the difference in distribution between universal and existential quantifiers and show how sentences can be analyzed so that a grammatical contrast aligns with a logical contrast: well-formed sentences are contingent, ill-formed sentences are trivial. Similar explanations have been proposed for many other phenomena, among which are the distinction between mass and count nouns (Chierchia, 1998, 2010), the distinction between individual-level and stage-level predicates (Magri, 2009), the distribution of polarity items (Krifka, 1995; Chierchia, 2013; Crnič, 2019), free choice (Menéndez-Benito, 2005; Crnič and Haida, 2020), numerals (Bylinina & Nouwen, 2018; Haida & Trinh, 2020, 2021), comparatives (Gajewski, 2008a), island effects (Fox & Hackl, 2006; Abrusán, 2007), question embedding (Uegaki & Sudo, 2017), just to name a few. The body of works carried out under the perspective of Logicality is large and growing.

I will now turn to the discussion of a problem for Logicality and a solution to it. This solution will be the key to resolving the inconsistency in Wittgenstein’s position on trivialities.

The problem might have become quite obvious to the astute reader, who will have noticed something strange in what we have said so far. On the one hand, we claim that sentences such as (7b) and (14b), repeated below as (16a) and (17a), are ill-formed because they have the trivial entailments in (16b) and (17b), respectively.

On the other hand, we seem to have no problem accepting these trivial entailments themselves, or more precisely, the sentences we use to convey them, as perfectly grammatical. Neither (16b) nor (17b) are ill-formed. But how do we square this fact with Logicality? Doesn’t Logicality predict all four sentences in (16) and (17) to be ungrammatical? The problem, in fact, can be illustrated more simply, but more dramatically, by the sentences in (6), repeated below.

If Logicality is correct, grammar should mark both of these sentences as ill-formed, given that (18a) is a contradiction and (18b) a tautology. But it clearly doesn’t. We can debate the reasons why someone would use (18a) or (18b), but we cannot deny that that person speaks English. Our perception of someone who produces (16a) or (17a), on the other hand, is very different: we would think that he has not mastered English. Thus, (18a) and (18b) are clearly well-formed in a way that (16a) and (17a) are not.

The problem for Logicality, then, is that it excludes more sentences than it should. It predicts all trivialities to be ungrammatical, while in fact only some are. To solve this problem, we have to find a way to distinguish between trivialities that are well-formed, such as (18a) and (18b), and trivialities that are ill-formed, such as (16a) and (17a). The solution I am going to present is one proposed by Del Pinal (2019); Pistoia-Reda and Sauerland (2021); Del Pinal (2022), among others. It is sometimes refered to as “contextualism”.Footnote 29 What it says is that natural language grammar contains a covert, context-sensitive “rescaling” operator, R\(_\text {c}\), which attaches to non-logical expressions and modulates their meaning. The logical form of (18a) is then not (19a) but (19b).

Similarly, the logical form of (18b) is not (20a) but (20b).

Note, importantly, that one and the same expression may attach to differently indexed rescaling operators. In other words, we allow non-logical terms to shift their meaning within the same sentence. The meaning of R\(_\text {c}\)(raining), then, does not have to be identical to that of R\(_\text {c'}\)(raining). This means (18a) has a non-trivial reading as saying ‘it is raining in some sense and not raining in some other sense’. In the same way, (18b) has a non-trivial reading. These readings kick in and rescue the sentences from being trivial, hence from being ill-formed. Speakers, however, may not be consciously aware of this process, just as they are not conciously aware of the fact that (16a) and (17a) are ill-formed because the former entails the contradiction in (16b) and the latter the tautology in (17b). The interaction between universal grammar and the natural deductive system takes place at a subconscious level. It results in intuitions on acceptability which speakers can viscerally experience but cannot explicate.

The question now is why the same rescaling process does not kick in and rescue (16a) and (17a) from being trivial, making them well-formed. Well, the answer is that even if it does kick in, it still cannot rescue these sentences from being trivial. Recall a condition on the rescaling operator: it can only attach to non-logical terms. Thus, it would not attach to except, every, a, and there, which are logical constants. Let us look at the logical form of (16a) and (17a).

The reader is invited to verify for herself that both (21a) and (21b) are trivial. Given the semantics proposed in (9), a(P except E)(Q) is contradictory under all values of P, E, and Q. Similarly, the semantics proposed in (15) predicts that there(every(P)) is tautologous under all values of P. Rescaling does not help in these cases.

I will end this section by mentioning an issue which the proponents of Logicality must address and which is also raised by Wittgenstein in the Tractatus. This is the issue of how to distinguish between logical and non-logical constants? For Wittgenstein, the logical constants are those expressions that will disappear in the proper semantic analysis: what they express, namely entailment relations, would emerge from the pictorial nature of the symbols in the ideal notation. Until we succeed in constructing such a notation, however, we have to deal with logical constants in our non-ideal language. Wittgenstein says of such expressions that they “do not represent” (4.0312). This description more or less captures our intution about such words as every, a, except, and there. The rescaling story works under the assumption that these words are logical constants. It is true, in some sense, that they do not “represent” anything. However, this description turns out to be too vague. It is not clear what would prevent me from saying, for example, that every represents the relation ‘is a subset of’, which is the set of pairs \(<\text {X}, \text {Y}>\) such that X \(\subseteq \) Y. We need a more rigorous definition of logical constants.

It turns out, however, that such a definition is quite difficult to formulate.Footnote 30 Gajewski (2003), based on ideas from previous works, suggests to define logical constants in terms of “permutation invariance”. Logical constants, then, would be those expressions whose denotation remains constant across permutations of individuals in the domain (Mautner, 1946; Mostowski, 1957; Tarski, 1986; van Benthem, 1989; McGee, 1996). This definition, for example, would include every in, and exclude student from, the set of logical constants. To illustrate, suppose our domain is \(\{a, b, c\}\), where a and b are students while c is not. The denotation of student is then \(\{a, b\}\). This set will become a different set, \(\{b, c\}\), under the permutation \([a\) \(\rightarrow \) \(b, b\) \(\rightarrow \) \(c, c\) \(\rightarrow \) \(a]\), which means student is not permutation invariant, hence not a logical constant. In contrast, every will denote the set in (22).

This set will obviously remain the same under all permutations, as switching the individuals around does not affect whether a set is a subset of another set: \(\{a\}\) will still be a subset of \(\{a, b\}\), hence the pair \(<\{a\}, \{a, b\}>\) will still end up in the denotation of every, for example. This means every is a logical constant, a good result. Gajewski’s suggestion is widely known and cited. However, it clearly cannot be the whole story, as it classifies predicates like exists or is self-identical, which supposedly denote the universe of discourse U, as logical,Footnote 31 even though these do not incur ill-formedness as we would expect (Abrusán, 2019; Del Pinal, 2022).

No matter how we modulate the meaning of man and student, the sets they denote will be a subset of U. There would then be no reading of these sentences in which they are not trivial. However, neither (23a) nor (23b) is ill-formed. This means that exists and self-identical are in fact not logical constants, as far as the language system is concerned, and that (23a) and (23b) can be analyzed as (24a) and (24b), where R\(_\text {c}\)(exists) and R\(_\text {c}\)(self-identical) do not denote U.

To the best of my knowledge, an adequate intensional definition of logical constants is still missing. At this stage, a wealth of data find illuminating explanations in terms of Logicality. These explanations appeal to an intuitive notion of “logical constants”, but the distinction they draw between logical and non-logical terms is, in the end, stipulative. It is, of course, also possible that the distinction will turn out to be essentially stipulative (Quine, 1951). The jury is still out.

3 Transformative analysis

Let us recap. In section 1, I argue that Wittgenstein takes trivialities to be well-formed even though the theory of language which he proposes, PTL, predicts them to be ill-formed. My hypothesis is that Wittgenstein’s inconsistency is rooted in his inadequate analysis of a class of natural language expressions: he analyzes a sentence such as (25), which is perceived to be perfectly well-formed, as having the logical form in (25a), which is a triviality. In section 2, I present a thesis recently developed in theoretical linguistics, Logicality, which provides a way to overcome this inadequacy: Logicality makes it possible, in fact necessary, to analyze (25) not as (25a) but as (25b), which is not a triviality.

In this section, I will comment on some points of contact between analytic philosophy and theoretical linguistics which have been brought into relief by our discussion.

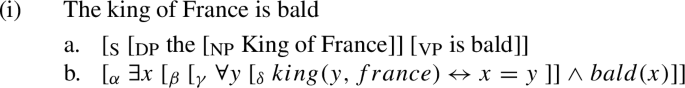

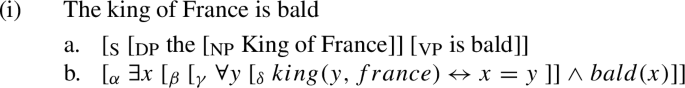

Analytic philosophy began with the insight that the “logical form” of a sentence, i.e. one which captures its semantic properties, might be quite different from its “surface form”, i.e. one which captures its syntactic, morphological and phonological properties. To illustrate, consider the sentence in (26). Its surface form is (26a), while its logical form would be (26b).Footnote 32

One can see how (26a) and (26b) differ with respect to their constituency. For example, there is no constituent of (26b) which corresponds to the object DP every boy in (26a). There are, in addition, four sentential constituents in (26b) – i.e. \(\alpha \), \(\beta \), \(\gamma \), and \(\delta \) – while there is only one such constituent in (26a), namely S.Footnote 33 The idea that (26b) could in principle be how (26) looks at some level of description constitutes a “revolution” in the way we think about natural language sentences: semantic analysis must be carried out on a structure different from one which inputs pronunciation or writing. Beaney (2016, p. 235) puts it succinctly: “[T]here is no decomposition without interpretation”. The term “interpretation” here is to be understood as ‘translation’ or ‘transformation’. Thus, semantic analysis consists of (i) the step of “transformative analysis” which translate the surface form of the sentence into its logical form, and (ii) the step of “decompositional analysis” which dissects the logical form and computes its consequences (Beaney, 2000, 2002, 2003, 2016, 2017).Footnote 34

It is at the step of transformative analysis, I submit, that Wittgenstein commits an error with sentences such as those in (18). He takes it for granted that the two instances of rain are one and the same symbol. It never occured to him to see this as a case of homophony, i.e. a case of two different symbols, R\(_\text {c}\)(rain) and R\(_\text {c'}\)(rain), having one and the same pronunciation. Curiously, Wittgenstein does discuss homophony in the Tractatus: “In everyday language it occurs extremely often that the same word signifies in different ways – that is, belongs to different symbols” (3.323). He even provides an example: “In the proposition ‘Green is green’ – where the first word is a person’s name, the last an adjective – these words [...] involve different symbols” (3.323). Note that the homophonous symbols in this case, “Green” and “green”, belong to different syntactic categories (noun and adjective). It is also obvious that the meaning of the first, the person named Green, and the meaning of the second, the color green, are different. Thus, it is much easier to see homophony here than to see it in the case of R\(_\text {c}\)(rain) and R\(_\text {c'}\)(rain), where the two symbols not only belong to the same syntactic category (verb), but also have meanings which differ in a much more subtle way (‘rain in one sense’ and ‘rain in another sense’).

Beaney’s dictum, that there is no decomposition without interpretation, implies that a sentence is associated with at least one structure which inputs pronunciation and one other structure which inputs interpretation. Transformative analysis is the step that relates the two. As it happens, the idea that a sentence is associated with more than one structure is foundational to modern linguistics. It brought about the “generative revolution” in the 1950’s (cf. Chomsky, 1988). In the current “minimalist” version of generative grammar which has established itself more or less as cannonical (Chomsky, 1991, 1995; Radford, 2004), a sentence is associated with two structures: a “phonological form” (PF) and a “logical form” (LF). PF inputs pronunciation while LF inputs interpretation. PF and LF are related by “transformational rules” which build complex structures from lexical items step by step.Footnote 35 Note that the LF of a sentence, just like the logical form which results from transformative analysis, can differ drastically from how we hear the sentence or see it written on paper. For example, the LF of (26) is (27) (Heim & Kratzer, 1998; Fox, 2000, 2003).

We can thus witness an interesting parallel between the “analytic revolution” in philosophy and the “generative revolution” in linguistics. A notable fact is that the former came much earlier. Its beginning can be dated to Frege’s 1879 debut, Begriffsschrift, wherein he proposes quantificational predicate logic (Beaney, 2016, 228). The beginning of generative grammar, in contrast, came with Chomsky’s (1955) magnum opus The Logical Structure of Linguistic Theory, wherein he proposes transformations. And it would take the linguists about 20 years more to come up with the idea of LF as a structure which disambiguates scopal relations between quantificational elements in the sentence (May, 1977; Chomsky, 1981; Huang, 1982; May, 1985).Footnote 36 What is the reason for this delay?

The answer, I believe, lies in the difference between early analytic philosophers and generative grammarians with respect to their view on the surface form of natural language sentences. For the former, it is more or less a mess. Serious investigation can only begin after transformative analysis, which is carried out by the philosopher contemplating on what the sentence means. However, the step of transformative analysis is itself shrouded in mystery: there is no theory of it. Coming up with the logical form of a sentence is, therefore, similar to scientific discovery in its spontaneous and revelatory nature. In contrast, generative grammarians take the relation between PF and LF to be systematic: both are derived by transformational rules, which are codified in a unified theory. This theory imposes constraints on possible sound–meaning associations and can thus account for intuitions which, I think, would remain puzzling to the philosophers. Take the phenomenon of “weak crossover”, for example. It is observed that (28a) can be associated with the meaning expressed by (28b) but (29a) cannot be associated with the meaning expressed by (29b). It is not clear how analytic philosophers would explain this contrast. Generative grammarians, on the other hand, have proposed several accounts of it (Koopman & Sportiche, 1983; Reinhart, 1983; May, 1985).

Part of generative grammar, then, can be seen as a proposal on how transformative analysis really works, thereby providing a missing link in analytic philosophy, which considers this step a black box. This would also make sense of the fact that the grammarians’ LF came long after the philosophers’ logical form: it is understandable that it takes more time to figure out how something works than to realize that it works.

Is there any missing link in generative grammar which is provided by analytic philosophy? At this point, I can only say “maybe”. Recall what Logicality claims: trivialities are ill-formed. The unacceptability of sentences excluded by Logicality is, crucially, of a different kind from that of sentences which violate “pragmatic” rules. To illustrate, compare (30a) and (30b).

Both sentences in (30) sound “odd”. However, there is a clear difference. A person who produces (30b) might be making a joke, or trying to be philosophical, or having some sort of mental problem, or all three, but she is speaking English.Footnote 37 Her sentence is well-formed. In contrast, a person who produces (30a) is not speaking English. Whatever rules out (30a), therefore, must be a component of formal grammar. Obviously, it is not phonology or morphology. There are no illegitimate combinations of phonemes or morphemes in (30a). This means (30a) fails at syntax. There are two possibilities for a sentence to “fail at syntax”. The first is that it cannot be derived by syntactic rules: formal properties of the words just do not allow them to be put together to build the sentence. An apt metaphor for this scenario would be a computer constructed with parts that do not fit. The second possibility is that the sentence can be derived by syntactic rules but the output “crashes” at the interface between syntax and the interpretive systems: it is not accepted by these systems as legitimate input. A metaphor for this scenario would be a computer which is built with parts that fit perfectly but which has no power port. In both cases, we have a defective product of syntax. It is syntactic defect that gives sentences such as (30a) their distinctive feel of “gibberish”. As far as I know, proponents of Logicality share the view that sentences such as (30a) fail in the second way: they can be derived by the syntactic rules but crash at the syntax-semantics interface. In other words, semantics imposes a “contingency constraint” on the output of syntax (Abrusán, 2019). I have not encountered claims in the literature to the effect that trivialities cannot be derived by syntactic rules, and it is not hard to see why. Syntactic rules are commonly assumed to be “blind” to interpretation. What they care about is whether something is a determiner, not whether its quantificational force is universal or existential. In that sense, syntactic rules do not distinguish between a and every.

A question that has not been raised, to the best of my knowledge, is why there should be a contingency constraint on the output of syntax. Why should structures which express trivialities be markedss as defective syntactic products? Analytic philosophy, I surmise, might help us towards settling this explanatory question. Specifically, the picture theory of language might provide a starting point for developing an answer to it. Thus, suppose we say that interpretation of syntactic structures means mapping them into expressions of a “translation language” TL which is, as it were, the “language of thought”.Footnote 38 And suppose, furthermore, that TL is “pictorial” in the sense envisioned by Wittgenstein. Then trivialities would be marked as defective products of syntax for the reason that they are “untranslatable”. This is, of course, speculative. My objective in this paper is to point out a tension in Wittgenstein’s theory of language and argue that it can be resolved in light of recent advances in linguistic research. This objective, I believe, can be achieved independently of whether my speculation about TL has merits. I do hope, however, that future work will show that it does.Footnote 39

4 A loose end

I have proposed that Wittgenstein’s exclusion of trivialities from nonsense is due, in part, to his intuition about the well-formedness of such sentences as (31).

However, Wittgenstein considers such sentences as (32) nonsensical (4.1272).Footnote 40

The existence of objects is a precondition for the meaningfulness of language (5.552). This precondition is “shown” by our use of the language. Attempts at “saying” it in the language would result in nonsense. Saying anything means picturing it, which implies it is contingent. But (32) is not contingent: we cannot picture it being false, simply because picturing is not possible if it is false.Footnote 41

But (32) is intuitively well-formed, just like (31). The question that arises, then, is whether my proposal is contradicted by the fact that Wittgenstein takes (32), but not (31), to be nonsensical? The answer, I submit, is no. I never claim intuitive well-formedness guarantees exclusion from nonsense. I only hypothesize that it helps. This hypothesis is compatible with (32) being deemed nonsensical by Wittgenstein. In fact, I would argue that Wittgenstein’s differential treatment of (31) and (32) supports the general theme of my proposal, which is that natural language intuition gives rise to issues in PTL that can be resolved by Logicality. The issue here is that both (31) and (32) are non-pictorial, but Wittgenstein only regards (32) as nonsense. Can we locate the source of this issue in natural language intuition? And can Logicality resolve it?

The answer to both questions, I believe, is yes. Consider (31). This sentence is derived from it’s raining, which is clearly pictorial, by (successive) application of negation and conjunction. This means that if Wittgenstein is to declare (31) nonsensical, he would have to “overcome” not only the natural language intuition that it is well-formed, but also the natural language intuition that (33) is true.

If we accept that it’s raining is well-formed, and accept that (33) is true, then we have to accept that (31) is well-formed. And it is overwhelmingly intuitive that (33) is true. The words not and and, intuitively, are sentential operators: they do not map sentences to non-sentences. Now consider (32). This expression, according to Wittgenstein, fails at the word level. It has no subconstituent which is pictorial. The word object is already meaningless, in the sense that it has no translation in the ideal notation. This means that declaring (32) nonsensical does not require abandoning (33). The only natural language intuition which must be overcome is that it is well-formed.

Thus, we can, arguably, locate the source of Wittgenstein’s differential treatment of (31) and (32) in natural language intuition, namely his intuition about not and and. Now let us ask whether the technology of Logicality, i.e. rescaling, would “resolve the issue”, i.e. would make it possible for Wittgenstein to treat (31) and (32) in the same way. The answer, clearly, is yes. Given rescaling, Wittgenstein could say, for both (31) and (32), that they are contingent under the rescaled analysis and trivial under the non-rescaled analysis.Footnote 42 And the fact that there is one analysis under which they are contingent is responsible for our experience of them as well-formed.

As far as I know, non-pictorial sentences which Wittgenstein deems nonsensical are all of the same type as (32): classifying them as ill-formed does not require abandoning (33). To the extent that I am correct, the above considerations apply generally.

5 Conclusion

Wittgenstein’s picture theory of language (PTL) unites grammar and logic as two different symptoms of the same underlying condition. A consequence of PTL, which Wittgenstein refuses to accept, is that trivialities are ill-formed. This turns out to be precisely what is claimed by Logicality, a recently developed thesis about natural language which has been corroborated by a large amount of empirical arguments. Logicality provides an explanation for Wittgenstein’s dissonant attitude towards trivialities. The discussion on PTL and Logicality brings out reasons to take a closer look at the historical relationship between analytic philosophy and generative linguistics as well as the way in which these two disciplines can complement each other going forward.

Notes

Or the Tractatus for short. This is the Latin rendition of the original German title (Logisch-philosophische Abhandlung), and was suggested by Moore as title for the English translation of Wittgenstein (1921). There are two well-known printed English translations. The first, published in 1922, was mostly the work of Frank P. Ramsey, even though Charles K. Ogden appeared as the translator. The second, by David F. Pears and Brian F. McGuiness, was published in 1961, with a revised version appearing in 1974. The publisher, in both cases, was Routledge and Kegan Paul (see Michael Beaney’s Introduction chapter in Wittgenstein 2023). There is a new English translation by Michael Beaney, Wittgenstein (2023), which is published by Oxford University Press. In what follows I will use Beaney’s translation, unless otherwise indicated. See note 4.

Wittgenstein originally intended the title of his book to be simply “Der Satz” (“The Sentence”) (cf. Goldstein 2002, citing Bartley III 1973.) Note that although Wittgenstein clearly distinguishes between legitimate and illegitimate combination of symbols, i.e. between sentences and non-sentences, he does not consistently use the term “grammar” in the way I am using it, but alludes to this distinction in a variety of ways. The term he most often uses to refer to non-sentences is “Unsinn” (nonsense). Combinations of symbols that are not nonsense are sentences. We will come back to this term below.

The German word “Satz” used by Wittgenstein in the Tractatus is rendered as “proposition” in the English translations. I will, however, use “sentence” as the English counterpart of “Satz”, as I think it conveys more faithfully what Wittgenstein means with “Satz”, namely the syntactic material in its semantic interpretation, not just the semantic interpretation: “[D]er Satz ist das Satzzeichen in seiner projektiven Beziehung zur Welt” (3.12). It seems to me that the word “proposition” has come, especially in the linguistic literature, to denote what the sentence expresses in abstraction from its syntax: two different sentences may express one and the same proposition. The reader will thus be asked to keep in mind that “proposition” in the quotes from Beaney’s English translation, which is the one I use here, and “sentence” in my own text, are just two different renderings of “Satz” in the German original.

The discussion is illustrative and the simplistic example I use will undoubtedly beg a lot of questions. I will not attempt to address these questions by adding a footnote qualifying virtually every clause in the next paragraphs. My hope is that the reader can muster enough charity to see the point I want to make without feeling too frustrated by the extreme informality and lack of precision in my exposition.

In what follows I will refer to sentences in (3) by using the name of the relevant language and the numbers in the first columns. Thus, L\(_\text {F}\)-2 is \(\lnot s(n)\), L\(_\text {W}\)-3 is the jar with the pebble inside and the marble outside of it, for example.

Wittgenstein also proposes the idea of illustrating PTL using arrangements of physical objects: “The essence of a propositional sign becomes very clear if we think of it as composed of spatial objects (such as tables, chairs, books) instead of written signs. The mutual spatial position of these things then expresses the sense of the proposition” (3.1431). Thus, Tractarian objects are not formless: they come with constraints on how they combine with other objects (Hope, 1969; Hintikka, 1994, 2000).

The syntax is usually set up in such a way that it contains rules for constructing sentences and a “restriction clause” which states that “nothing else is a sentence”, i.e. that only those structures which can be generated by the rules which have been provided are sentences. This clause excludes non-sentences.

We can, of course, “imagine” a (tiny) jar being inside a (huge) marble. But I am illustrating PTL with real objects, not imaginary objects. There is no point in using imaginary objects to illustrate the difference between L\(_\text {F}\) and L\(_\text {W}\), as combining imaginary objects would be, of course, as unconstrained as combining letters. I believe, also, that the “tables, chairs, books” that Wittgenstein is talking about in 3.1431 are real, not imaginary (see note 8): he is not talking about imaginary tables and chairs that could be inside of imaginary books. I thank an anonymous reviewer to drawing my attention to the need to clarify this point.

The rule in (4a) is sometimes called “simplication”. The logic, just like the syntax, is usually set up in such a way that it contains rules of inference and a restriction clause stating that “no other inference is valid” (see note 9).

The reader might wonder whether L\(_\text {W}\)-1 entails Mary doesn’t smoke, as it shows that only the pebble is inside the jar, i.e. that only John smokes. This is certainly an intuition that we have about L\(_\text {W}\)-1. It is here that our simple example breaks down, the confound being how we, as “cooperative” language users, tend to enrich the message conveyed by a sentence. Specifically, we tend to take the sentence to say not only that the states of affairs it represents are facts but also that these facts are all the facts (Grice, 1967). Thus, the sentence John smokes, as an answer to who smokes?, is most naturally interpreted as saying not only that John smokes but also that no one else smokes (Groenendijk & Stokhof, 1984; Heim, 1994; Chierchia et al., 2012; Trinh, 2019). In the case of L\(_\text {W}\)-1, we tend to see it as conveying not only that the pebble is inside the jar, but also, as conveying that the marble is not inside the jar. Note that the issue then arises as to why we seem not to see L\(_\text {W}\)-1 as saying that the marble is not outside the jar. Given that we do not see the marble in L\(_\text {W}\)-1 at all, supplying the picture mentally with the marble being inside the jar and supplying it mentally with the marble being outside the jar should be two equally good options. The linguistic counterpart of this issue is known as the “symmetry problem” (Kroch, 1972; Fox, 2007; Fox & Katzir, 2011; Trinh & Haida, 2015; Trinh, 2018, 2019). To the best of my knowledge, no studies have been done on how a “pictorial” variant of this issue, as informally presented here, might help adjudicate between competing proposals, especially regarding the notion of “conceptual alternatives” (Breheny et al., 2018; Buccola et al., 2022). This whole topic deserves a lot more discussion than I am able to provide in this short note. I hope to return to it on another occasion.

We could revise the syntax of L\(_\text {F}\) as to disallow the conjunction of a sentence and its negation. However, such a revision would be completely ad hoc.

Another way to write \(\lnot (s(j) \wedge \lnot s(j))\) is \(s(j) \vee \lnot s(j)\), given the definition of \(\vee \) as the dual of \(\wedge \).

As we know, the practice of filling a gap in a chain of reasoning by a conjecture is common in mathematics.

See Chomsky (1981). Basically, the \(\Theta \)-Criterion requires that the number of syntactic arguments of a predicate match exactly the number of its logical arguments. The Socrates example is presented in 5.473 and 5.4733.

I thank an anonymous reviewer for drawing my attention to this line of thinking.

I thank an anonymous reviewer for pointing this out.

The same argument can be made with respect to the term “Elementarsatz” (atomic sentence): when Wittgenstein says “Satz”, he means ‘Satz’, not ‘Elementarsatz’. In fact, this is the main argument of Eisenthal (2023).

I should stress, also, that an inconsistency does not necessarily make a theory “bad” or mean that its proponents are intellectually inferior. The Standard Model is inconsistent with General Relativity, but physical theory remains the crown jewel of scientific achievement by the greatest minds. An inconsistency may arise from several theses, each of which seems unavoidable, but all of which cannot be simultaneously true, as is the case, I believe, with A, B and C in Wittgenstein’s theory of language. This can make the theory fruitful, as it stimulates further thought and investigation. I provide this footnote in awareness of possible reactions to my paper as shown by one colleague who, after I presented it, said to me: “Wittgenstein is not an idiot!” Of course Wittgenstein is not an idiot. He is a deep thinker whose ideas foreshadowed one of the most important discoveries in linguistics. His contribution would have been greatly diminished, I think, if he retreats into the safe space of consistency and restricts his picture theory to sentences which obviously pose no challenge to this theory.

Again, I note that “well-formed” and “ill-formed” are not terms used in the Tractatus. I hope, however, that my use of these terms, given the explanation I just gave, will cause no confusion. I thank an anonymous reviewer for pointing out the need to make it clear that “ill-formed” is not used by Wittgenstein.

As pointed out, interestingly, by Peters and Westerståhl (2023), the observation about exceptives was made as early as in the 14th century by William Ockham: “An exceptive proposition is never properly formed unless its non-exceptive counterpart is a universal proposition. Hence, a man except Socrates is running is not properly formed” (Summa Logicae Part II:18, translated by Alfred J. Freddoso and Henry Schuurman).

The reader will notice that I am mixing object and metalanguage. My use of every, for example, is ambiguous between the expression and the relation it denotes. I hope no confusion results from this informality.

We assume that student denotes the set of students, i.e. the set \(\{x\) | x is a student\(\}\), and the name John can be “type-shifted” to denote the singleton set containing John, i.e. the set \(\{\)John\(\}\) (Partee, 1986).

The reader can also verify that (9) explains not only the contrast between every and a but that between universal quantifiers (e.g. every, all, no) and existential quantifiers (e.g. a, some, most) in general. Note, also, that my presentation of von Fintel (1993) differs from the original in one minor detail: whereas I take the phrase except John to be a modifier of student, von Fintel takes it to be a modifier of the determiner. This difference has no bearing on the point being made. Since von Fintel (1993) other accounts of exceptive constructions have been proposed, most of which also explain the ill-formedness of (7b) by reducing it to a contradiction (Gajewski, 2008b; 2013; Crnič, 2021; Vostrikova, 2021), but some of which explain it in other ways (Moltmann, 1995; Hirsch, 2016).

We will assume, for simplicity, that the copula is is not interpreted (Heim & Kratzer, 1998).

Assuming that fly in my soup denotes the set of flies in my soup, i.e. \(\{x\) | x is a fly in my soup\(\}\).

For an overview of attempts at characterizing the notion of a “logical constant” see MacFarlane (2017).

Obviously, U remains the same under all permutations of the individuals in it.

Another example of this approach is Frege’s analysis of numerical statements (Frege, 1884; Reck, 2007; Levine, 2007). The most well-known example is perhaps Russell’s (1905) analyis of definite descriptions: the surface form of (i) is (ia) while its logical form is (ib).

According to Russell’s analysis, (i) says that there is exactly one king of France who is bald. The analysis predicts the sentence to be meaningful, i.e. truth-valuable, without France being a monarchy. This is an empirical prediction, and we can debate in what way it is correct and in what way it is not. For analyses of definite descriptions which differ from Russell’s in that they do not make this prediction, see Frege (1884, 1892); Strawson (1950); Heim (1982, 1991).

The sentence in (30b) exemplifies what is called “Moore’s Paradox”, as it was G. E. Moore who noticed that sentences of the form \(\phi \) but I don’t believe that \(\phi \) are odd (Moore, 1942). It can be shown that given Grice’s 1967 maxims of conversations and standard assumptions about belief, the speaker of (30b) has contradictory beliefs (Schlenker, 2016).

For such a translation approach to semantic interpretation see Montague (1973).

The greatest challenge to a theory of TL would seem to be intensional contexts: A thinks p, must p, etc. Wittgenstein suggests to analyze A thinks p as depicting a situation where two configurations of objects mirror each other, one of which represents, presumbaly, A’s thought and the other represents p (5.542). Thus, A thinks p describes a fact about the world, just like it is raining. To the extent that such an extensional analysis is conceivable, there is no principled reason for insisting that a pictorial representation is impossible in this case. The same argument can be made for modals. In fact, the “double relative” analysis of modality, which has more or less become consensus among linguists, would say that a sentence like John must pay a fine depicts, for example, a situation where John has parked his car in the driveway and the relevant rules specify that parking one’s car in the driveway incurs a fine (Kratzer, 1977, 1981, 1991; von Fintel & Heim, 2011). I thank an anonymous reviewer for raising the issue of modal sentences.

I thank an anonymous reviewer for pointing out that sentences such as (32) should be discussed.

To see how (32) cannot be said in a Tractarian pictorial language, imagine we have to use the language discussed in section 1 – with the pebble (John), the marble (Mary), and the jar (smoking) – to say that John exists. Obviously, we cannot. Note, importantly, that holding up the pebble, which is the symbol for John, is not “saying” anything. The natural language counterpart to that would be uttering just the word John. Of course, such an utterance may be understood as saying something, if the word John is interpreted as if it is part of a sentence. Suppose the question who smokes? has been asked, for example. Uttering John in response would then amount to saying that John smokes. This example, clearly, does not show that words can be meaningful in isolation. In fact, it shows the opposite: it corroborates Frege’s “context principle” (Frege, 1884), which Wittgenstein also assumes, that a word can only be interpreted as part of a sentence (2.0122). The fact that sentences in natural language can be elliptical, i.e. can contain parts that are not pronounced, presents no challenge to this principle.

The word object can be rescaled to mean ‘physical objects in the visual field’, for example.

References

Abrusán, M. (2007). Contradiction and Grammar: The Case of Weak Islands. Doctoral Dissertation, MIT.

Abrusán, M. (2019). Semantic anomaly, pragmatic infelicity, and ungrammaticality. Annual Review of Linguistics, 5, 329–351.

Anscombe, G. E. M. (1959). An Introduction to Wittgenstein’s Tractatus. University of Pennsylvania Press.

Bartley, I. I. I., & Warren, W. (1973). Wittgenstein. J. B. Lippincott Company.

Barwise, J., & Cooper, R. (1981). Generalized quantifiers and natural language. Linguistics and Philosophy, 4, 159–219.

Beaney, M. (2007). The analytic turn in early twentieth-century philosophy. In M. Beaney (Ed.), The Analytic Turn. Analysis in Early Analytic Philosophy and Phenomenology (pp. 1–30). Routledge.

Beaney, M. (2000). Conceptions of analysis in early analytic philosophy. Acta Analytica, 15, 97–115.

Beaney, M. (2002). Decompositions and transformations: Conceptions of analysis in the early analytic and phenomenological traditions. Southern Journal of Philosophy, 40, 53–99.

Beaney, M. (2003). Russell and Frege. In N. Griffin (Ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Bertrand Russell (pp. 128–170). Cambridge University Press.

Beaney, M. (2016). The analytic revolution. Royal Institute of Philosophy Supplements, 78, 227–249.

Beaney, M. (2017). Analytic Philosophy: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press.

Biletzki, A., & Matar, A. (2021). Ludwig Wittgenstein. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, Winter 2021 edition.

Breheny, R., Klinedinst, N., Romoli, J., & Sudo, Y. (2018). The symmetry problem: Current theories and prospects. Natural Language Semantics, 26, 85–110.

Buccola, B., Križ, M., & Chemla, E. (2022). Conceptual alternatives. Competition in language and beyond. Linguistics and Philosophy, 45, 265–291.

Bylinina, L., & Nouwen, R. (2018). On “zero" and semantic plurality. Glossa: A Journal of General Linguistics, 3, 1–23.

Chierchia, G. (1998). Reference to kinds across languages. Natural Language Semantics, 6, 339–405.

Chierchia, G. (2006). Broaden your views: Implicatures of domain widening and the “logicality’’ of language. Linguistic Inquiry, 37, 535–590.

Chierchia, G. (2010). Mass nouns, vagueness and semantic variation. Synthese, 174, 99–149.

Chierchia, G. (2013). Logic in Grammar. Oxford University Press.

Chierchia, G., Fox, D., & Spector, B. (2012). The grammatical view of scalar implicatures and the relationship between semantics and pragmatics. In P. Portner, C. Maienborn, & K. von Heusinger (Eds.), Semantics: An International Handbook of Natural Language Meaning (pp. 2297–2332). De Gruyter.

Chomsky, N. (1955). The Logical Structure of Linguistic Theory. Harvard University and MIT.

Chomsky, N. (1957). Syntactic Structures. Mouton.

Chomsky, N. (1965). Aspects of the Theory of Syntax. MIT Press.

Chomsky, N. (1981). Lectures on Government and Binding. Foris.

Chomsky, N. (1986). Knowledge of Language. Praeger Publishers.

Chomsky, N. (1988). The Generative Enterprise: A Discussion with Riny Huybregts and Henk van Riemsdijk. Foris.

Chomsky, N. (1991). Some notes on economy of derivation and representation. In R. Freidin (Ed.), Principles and Parameters in Comparative Grammar (pp. 417–454). MIT Press.

Chomsky, N. (1995). The Minimalist Program. MIT Press.

Chomsky, N. (2007). Approaching UG from below. In U. Sauerland & H.-M. Gärtner (Eds.), Interfaces + Recursion = Language? Chomsky’s Minimalism and the View from Syntax-Semantics. Mouton de Gruyter.

Chomsky, N. (2008). On phases. In R. Freidin, C. Otero, & M. L. Zubizarreta (Eds.), Foundational issues in linguistic theory (pp. 133–166). MIT Press.

Chomsky, N. (2013). Problems of projection. Lingua, 130, 33–49.

Copi, I. M. (1958). Objects, properties, and relations in the Tractatus. Mind, 67, 145–165.

Crnič, L. (2021). Exceptives and exhaustification. Talk given at WCCFL 39.

Crnič, L., & Haida, A. (2020). Free choice and divisiveness. Lingbuzz/005217.

Crnič, L. (2019). Any: Logic, likelihood, and context. Language and Linguistic Compass, 13, 1–20.

Daitz, E. (1953). The picture theory of meaning. Mind, 62, 184–201.

Del Pinal, G. (2019). The logicality of language: A new take on triviality, “ungrammaticality”, and logical form. Noûs,53, 785–818.

Del Pinal, G. (2022). Logicality of language: Contexualism versus semantic minimalism. Mind, 131, 381–427.

Eisenthal, J. (2023). Propositions as pictures in Wittgenstein’s Tractatus: A sketch of a new interpretation. In 100 Years of Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus—70 Years after Wittgenstein’s Death. A Critical Assessment, ed. Alois Pichler, Esther Heinrich-Ramharter, and Friedrich Stadler, volume XXIX of Beiträge der Österreichischen Ludwig Wittgenstein Gesellschaft, 165–172. Kirchberg am Wechsel: ALWS.

Fox, D. (2000). Economy and Semantic Interpretation. MIT Press.

Fox, D. (2003). On Logical Form. In R. Hendrick (Ed.), Minimalist Syntax (pp. 82–123). Blackwell.

Fox, D. (2007). Too many alternatives: Density, symmetry and other predicaments. Proceedings of SALT, 17, 89–111.

Fox, D., & Hackl, M. (2006). The universal density of measurement. Linguistics and Philosophy, 29, 537–586.

Fox, D., & Katzir, R. (2011). On the characterization of alternatives. Natural Language Semantics, 19, 87–107.

Frege, G. (1879). Begriffsschrift: Eine der arithmetischen nachgebildete Formelsprache des reinen Denkens. Neubert.

Frege, G. (1884). Die Grundlagen der Arithmetik. Verlage Wilhelm Koebner.

Frege, G. (1892). Über Sinn und Bedeutung. Zeitschrift für Philosophie und philosophische Kritik, 100, 25–50.

Gajewski, J. (2003). L-analyticity in natural language. Unpublished manuscript.

Gajewski, J. (2008). More on quantifiers in comparative clauses. Proceedings of SALT, 18, 340–357.

Gajewski, J. (2008). NPI any and connected exceptive phrases. Natural Language Semantics, 16, 69–110.

Gajewski, J. (2013). An analogy between a connected exceptive phrase and polarity items. In E. Csipak, R. Eckardt, & M. Sailer (Eds.), Beyond ‘Any’ and ‘Ever’ (pp. 183–212). Walter de Gruyter.

Goldstein, L. (2002). How original a work is the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus? Philosophy, 77, 421–446.

Grice, P. (1967). Logic and conversation. In P. Grice (Ed.), Studies in the Way of Words (pp. 41–58). Harvard University Press.

Groenendijk, J., & Stokhof, M. (1984). Studies on the Semantics of Questions and the Pragmatics of Answers. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Amsterdam.

Haida, A., & Trinh, T. (2021). Splitting atoms in natural language. In Formal Approaches to Number in Slavic and Beyond, ed. Mojmír Dočekal and Marcin Wa̧giel, 277–296. Language Science Press.

Haida, A., & Trinh, T. (2020). Zero and triviality. Glossa: A Journal of General Linguistics, 5, 1–14.

Hauser, M., Chomsky, N., & Fitch, T. (2002). The faculty of language: What is it, who has it, and how did it evolve? Science, 298, 1569–1579.

Heim, I. (1982). The Semantics of Definite and Indefinite Noun Phrases. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Massachusetts at Amherst.

Heim, I. (1991). Artikel und Definitheit. In A. von Stechow & D. Wunderlich (Eds.), Semantik: Ein internationales Handbuch der zeitgenössischen Forschung (pp. 487–535). De Gruyter.

Heim, I. (1994). Interrogative semantics and Karttunen’s semantics for know. Proceedings of IATL, 1, 128–144.

Heim, I., & Kratzer, A. (1998). Semantics in Generative Grammar. Blackwell.

Hintikka, J. (1994). An anatomy of Wittgenstein’s picture theory. In C. C. Gould & R. S. Cohen (Eds.), Artifacts, Representations and Social Practice: Essays for Marx Wartofsky (pp. 223–256). Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Hintikka, J. (2000). On Wittgenstein. Wadsworth.

Hirsch, A. (2016). An unexceptional semantics for expressions of exception. UPenn Working Papers in Linguistics, 22, 139–148.

Hope, V. (1965). Wittgenstein’s Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus and the Picture Theory of Meaning. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Edinburgh.

Hope, V. (1969). The Picture Theory of Meaning in the Tractatus as a development of Moore’s and Russell’s Theories of Judgment. Philosophy, 44, 140–148.

Huang, C.-T. J. (1982). Logical Relations in Chinese and the Theory of Grammar. Doctoral Dissertation, MIT.

Keyt, D. (1964). Wittgenstein’s picture theory of language. The Philosophical Review, 73, 493–511.

Koopman, H., & Sportiche, D. (1983). Variables and the Bijection Principle. The Linguistic Review, 2, 139–160.

Kratzer, A. (1991). Modality. In A. von Stechow and D. Wunderlich (Eds.), Semantics: An International Handbook of Contemporary Research (pp. 639–650). De Gruyter.

Kratzer, A. (1977). What “must’’ and “can’’ must and can mean. Linguistics and Philosophy, 1, 337–355.

Kratzer, A. (1981). The notional category of modality. In H.-J. Eikmeyer & H. Rieser (Eds.), Words, Worlds, and Contexts: New Approaches in Word Semantics (pp. 38–74). De Gruyter.

Krifka, M. (1995). The semantics and pragmatics of polarity items. Linguistic Analysis, 25, 209–257.

Kroch, A. (1972). Lexical and inferred meanings for some time adverbials. Quarterly Progress Reports of the Research Laboratory of Electronics, 104, 260–267.

Levine, J. (2007). Analysis and abstraction principles in Russell and Frege. In M. Beaney (Ed.), The Analytic Turn. Analysis in Early Analytic Philosophy and Phenomenology (pp. 51–74). Routledge.

MacFarlane, J. (2017). Logical constants. In E.N. Zalta (Ed.) The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, Winter 2017 edition.

Magri, G. (2009). A theory of individual-level predicates based on blind mandatory scalar implicatures. Natural Language Semantics, 17, 245–297.

Mautner, F. I. (1946). An extension of Klein’s Erlanger program: Logic as Invariant-theory. American Journal of Mathematics, 68, 345–384.

May, R. (1977). The Grammar of Quantification. Doctoral Dissertation, MIT.

May, R. (1985). Logical Form: Its Structure and Derivation. MIT Press.

McGee, V. (1996). Logical operations. Journal of Philosophical Logic, 25, 567–580.

McGinn, M. (2006). Wittgenstein’s early philosophy of language and the idea of ‘the single great problem’. In A. Pichler and S. Säätelä (Eds.), Wittgenstein: The Philosopher and His Works (pp. 107–140). Ontos Verlag.