Abstract

Rawls’ notion of reflective equilibrium has a hybrid character. It is embedded in the pragmatist tradition, but also includes various Kantian and other non-pragmatist elements. I argue that we should discard all non-pragmatist elements and develop reflective equilibrium in a consistently pragmatist manner. I argue that this pragmatist approach is the best way to defend reflective equilibrium against various criticisms, partly by embracing the critiques as advantages. I begin with discussing how each of the three versions of reflective equilibrium in Rawls’ work combines pragmatist and non-pragmatist elements. For Rawls, the primary purpose of reflective equilibrium is epistemic: namely, to construct moral theories or judgments. In a pragmatist approach, there are three connected purposes for moral inquiry: right action, reliable understanding and self-improvement. Depending on the specific context of a reflective equilibrium process, these general purposes can give rise to a variety of specific purposes. In the next sections, I develop a pragmatist approach to reflective equilibrium and discuss the implications of this approach for core elements of reflective equilibrium. These elements are: the initial convictions, facts, personal commitments and comprehensive views of life, coherence and additional methods for critical scrutiny.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Since John Rawls’ introduction of the notion of reflective equilibrium, it has become very popular, especially in applied ethics.Footnote 1 The basic idea is simple: In a process of mutual adjustment, we seek coherence among the widest possible set of beliefs. However, beyond this core, there is considerable variation and lack of detail. Rawls has developed three versions to which others have added their own, but it remains unclear which version is to be preferred in which situation. When researchers refer to it, it is usually more a vague general approach than a sophisticated elaborate methodology.

Moreover, it is highly controversial. The critiques are well known: It does not provide certainty, moral truth, or universal theories; it is merely the systematization of our prejudices; it relies on rationalist, individualist and liberal presuppositions, and is therefore not neutral at all.Footnote 2 John Rawls and Norman Daniels, the most influential advocates of the method, have tried to rebut these criticisms, but these efforts have failed to convince most critics.

My suggestion is that both the methodological lacuna and the enduring criticism can be explained by the hybrid character of reflective equilibrium as presented by Rawls. On the one hand, it is embedded in the pragmatist tradition; on the other hand, his theory is highly Kantian in natureFootnote 3 and includes various other non-pragmatist elements. These two lines of thought, the pragmatist and the non-pragmatist, do not fit well together. In this article, I will argue that we should discard all non-pragmatist elements and develop reflective equilibrium in a consistently pragmatist manner. A pragmatist understanding of reflective equilibrium offers the best possible defense against the criticisms, many of which in fact can be perceived as advantages.Footnote 4

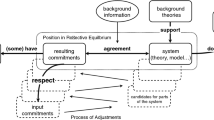

It is helpful to distinguish here between the general notion of reflective equilibrium and more specific versions. The general notion of reflective equilibrium as developed by Rawls and Daniels is almost empty and does not provide much methodological guidance; it merely holds that we should seek coherence between at least three levels: considered judgements, principles, and background theories. I do not discuss this general notion but only the specific conceptions or versions that Rawls has developed and elaborated. My claim is not that the general notion of reflective equilibrium is Kantian; my claim is merely that the three specific conceptions that Rawls developed in 1951, 1971 and 1993 are a mix of pragmatist and Kantian elements, and that we should remove the Kantian elements. Even so, this project requires more than merely removing some elements from the Rawlsian versions. It also implies rethinking the purposes of reflective equilibrium, and focus on additional processes to critically scrutinize our convictions and ourselves.

I should start by explaining what I mean by pragmatism. Obviously, I will not be able to do justice to all variations in the pragmatist tradition. Nor will I be able to defend it here. I only discuss those characteristics that are most relevant for moral inquiry and reflective equilibrium.Footnote 5 According to Catherine Legg and Christopher Hookway, the core notion is that pragmatism “understands knowing the world as inseparable from agency within it”.Footnote 6 In addition to this core idea, David Luban mentions eight “isms” that are characteristic of pragmatism, of which the first three are most important for our purpose: namely, anti-foundationalism, contextualism, and conceptual conservatism.Footnote 7 Pragmatism is anti-foundationalist because it rejects the notion that there are foundational or basic beliefs: all beliefs are uncertain and open to scrutiny. It is contextualist in the sense that justification is contextual; it varies both with the context of action and with the actor and the audience.Footnote 8 It is conceptually conservative because it starts from our current convictions and concepts, and only revises them when we have good reasons to do so.Footnote 9 We can critically scrutinize everything, but not everything at the same time. Otto Neurath’s famous metaphor of rebuilding a ship piecemeal on the open sea is often quoted by pragmatists.Footnote 10 To complete the list of what I take to be characteristics of pragmatism that are most relevant to moral inquiry, I return to Legg and Hookway. They add two characteristics, namely that pragmatism is fallibilist: that is, the focus of inquiry is not on how we can possess absolute certainty but on how we can make fallible progressFootnote 11 and that inquiry is a communal enterprise, as it focuses on the community of inquirers.Footnote 12

Within this broad characterization of pragmatism, there is still much variation. Some pragmatists have been influenced by Kant, others by Hegel. The existence of a tradition of Kantian pragmatism, including Charles Peirce, C.I. Lewis, Catherine Z. Elgin and Jürgen Habermas may shed doubt on my attempt to remove all Kantian elements from reflective equilibrium. To avoid misunderstanding: I do not suggest that we should purge pragmatism in general from Kantian elements, I merely suggest that we should get rid of all Kantian elements in reflective equilibrium and develop it in a Deweyan pragmatist way. My own version of pragmatism is indebted to the pragmatists inspired by Hegel, such as the younger John Dewey and Philip Selznick.Footnote 13

Reflective equilibrium has been mostly used in the contexts of ethics and political philosophy, but it need not be restricted to these. Goodman, for example, originally introduced his version to analyze rules of logic, and Elgin elaborated it for the contexts of scientific inquiry and art.Footnote 14 In this article, I will focus on moral inquiry. I use “moral” in a broad sense here, including political and legal philosophical questions. Moral inquiry may be loosely defined as an inquiry in which the moral dimension is predominant.Footnote 15 The different contexts of inquiry, on the one hand moral and political philosophy, and on the other hand science, give rise to many differences.Footnote 16 More importantly, it seems as if after a common ground in Goodman (1955), the two discourses have developed independently. In the practical philosophy discourse, Norman Daniels’ interpretation of Rawls is dominant, whereas Goodman and Elgin have inspired various authors from Switzerland and Germany, including the editors of this collection of essays and Tanja Rechnitzer (2022). Yet, the core authors do not refer to each other, let alone that they discuss each other.Footnote 17 My article tries to bridge both discourses; it is a contribution to the discourse in ethics and political philosophy, but it includes valuable insights from Elgin.Footnote 18

This article begins with an analysis of the hybrid character of Rawls’ versions of reflective equilibrium (Sect. 2). In the following sections, I develop a pragmatist understanding of reflective equilibrium. This is not a complete sketch—I only discuss some core issues where a pragmatist approach takes a different approach than a Rawlsian one.Footnote 19 In Sect. 3, I argue that the goal of moral inquiry should not merely be to justify moral theories and decisions, but that it has three connected purposes: right action, reliable understanding, and self-improvement. In Sects. 4 through 7, I discuss four notions that are central to reflective equilibrium methodology: initial convictions (Sect. 4); facts, comprehensive views, and personal commitments (Sect. 5); coherence (Sect. 6); and additional methods for critical scrutiny (Sect. 7). In Sect. 8, I discuss advantages of my pragmatist approach as well as possible objections. I finish with some general conclusions.

This article is not meant as a critique of Rawls or Kant, let alone as an exegesis or a critical reconstruction of either. Its main aim is constructive: it develops an alternative, consistently pragmatist approach to reflective equilibrium. I should make clear at the start that this is a general roadmap, a general perspective, rather than a detailed methodology. A pragmatist approach is thoroughly pluralist and contextualist. Therefore, there are many legitimate versions of reflective equilibrium; as I will argue below, an elaborate methodology can only be developed in light of the context and the specific purposes of a research project.

2 The hybridity of Rawls’ versions of reflective equilibrium

Obviously, this section cannot do justice to the full richness of Rawls’ work and the secondary literature. I merely want to demonstrate the hybridity in Rawls’ work. For overviews, see the literature mentioned in footnote 2 above.

Frequently, authors refer to reflective equilibrium as if it is one unambiguous method. However, Rawls developed at least three versions: in 1951, 1971 and 1993.Footnote 21 Norman Daniels further elaborated the latter two versions.Footnote 22 Nelson Goodman and Catherine Elgin also developed their own versions.Footnote 23 The theoretical literature presents numerous other minor or major modifications.Footnote 24 In applied ethics, Rawls’ 1971 version has been the main starting point for adapting the Rawlsian idea for specific practical purposes.Footnote 25 Therefore, we should start with exploring the Rawlsian versions, even if I will later suggest that we should deviate from them in major respects.

In 1951, Rawls presents an outline for a decision procedure in ethics.Footnote 26 The aim is to establish the objectivity of moral rules, and to construct moral principles that can be the basis for justified moral decisions. His method is largely inductive.Footnote 27 We should imagine competent judges who form considered judgments with regard to concrete moral problems. Using induction and various critical methods and tests, they construct reasonable moral principles.

The most elaborate version is presented in 1971. The aim is to construct a theory of justice for a well-ordered, almost perfectly just society.Footnote 28 The method has become fully coherentist: “justification is a matter of the mutual support of many considerations, of everything fitting together into one coherent view.”Footnote 29 The competent judges have been replaced by persons in the original position behind a veil of ignorance.Footnote 30 Background theories on the person and procedural fairness are invoked to justify this procedural mechanism, but controversial religious views and knowledge of concrete facts are excluded from the process. Considered judgments can now both be general principles and judgments with regard to concrete cases.Footnote 31

In 1993, there are two types of reflective equilibrium. The freestanding module of political reflective equilibrium is a theory for the political order of our liberal democratic, deeply pluralist society. This theory is supported by an overlapping consensus. But this restricted module is embedded in a variety of comprehensive theories that include background theories and theories of the good; some of these will be the result of a comprehensive reflective equilibrium.

Each of these three versions is hybrid in character containing both pragmatist and non-pragmatist elements. However, the mix is different in each. Pragmatist elements common to all three versions are the idea that we should use induction, starting with our own set of convictions and the principles that our tradition has produced. In 1971, the pragmatist elements become more prominent, with references to coherentism and to pragmatist philosophers such as Goodman and Quine.Footnote 32 The notions of feasibility and stability in 1971 also fit in the pragmatist tradition, and so does the idea in 1993 that the aim of political reflective equilibrium is to reconstruct our society’s sense of justice. In 1971, the hybrid character is most visible, as along with the pragmatist elements, many Kantian ideas are introduced, such as the notion of a social contract, the Kantian theory of persons as free and equal rational beings, the categorical imperative, the original position, the exclusion of controversial religious views and concrete facts, and the independence constraints.Footnote 33

There are good reasons for Rawls to adopt the Kantian elements. As his aim is to develop an Archimedean point or a generally acceptable theory, merely starting from initial convictions will not work. There would be too much contingency, and too much risk of prejudice, bias, distortions resulting from self-interest, and other types of error. In 1971, he expresses the ambition that, ideally, we should reach moral truths by strict deductive reasoning, by a moral geometry. He immediately adds that this is not possible, but the Kantian elements help to imitate and approximate that kind of strict reasoning as much as possible.Footnote 34 Rawls tries to convince proponents of alternative contemporary theories that his method is respectable and reliable, and that it can do justice to the core insights of those alternatives. As the most important of these alternatives—utilitarianism and intuitionism—are foundationalist and have universal claims, he needs to show that even though he offers no strict foundations, his method comes reasonably close. Consequently, the incorporation of Kantian elements in Rawls’ theory serves three functions. They counter bias and errorFootnote 35 they incorporate some of the most plausible and attractive insights of competing traditions, thereby making Rawls’ syncretic theory more attractive to readers from those traditions; and they make his theory less vulnerable to various criticisms, such as that it merely systematizes our prejudices.

However, this does not suffice for critics.Footnote 36 They argue that reflective equilibrium does not provide moral certainty or truth (which is correct, of course, but they are not what Rawls is after). The reasoning is not strict enough; for instance, if we modify the original position in relatively minor ways, we get a different theory of justice.Footnote 37 Moreover, the incorporation of these non-pragmatist elements comes at a price. They give rise to new biases—for example, by presupposing an individualist theory of the person. The focus on ideal theory and abstract principles does not take context and variation seriously enough. Stability and feasibility are not only a matter of general social theory but also of whether certain institutions are feasible in our concrete situation. The exclusion of knowledge of our concrete situation thus deprives us of an important part of our moral understanding.

The amalgam of pragmatist and non-pragmatist elements makes no one happy. Skipping the pragmatist elements to make reflective equilibrium more acceptable to foundationalists is impossible.Footnote 38 The pragmatist idea of going back and forth between our initial convictions is the core notion of reflective equilibrium, but the reliance on contingent and partly false initial convictions is unpalatable to most foundationalists. However, we can skip the non-pragmatist elements, as they are not crucial to the core of reflective equilibrium. The fact that hardly any of these elements are present in all three Rawlsian versions of reflective equilibrium testifies to that. Therefore, the best strategy is to develop reflective equilibrium in a consistently pragmatist way. Of course, we might also simply discard reflective equilibrium altogether. Nevertheless, as it is a widely used, perhaps even inevitable, method that fits very well with our common sense,Footnote 39 we should only do so if it is really necessary.

3 Purposes

A crucial difference between a Rawlsian and a pragmatist version of reflective equilibrium concerns the purposes. For Rawls, the epistemic purpose of reflective equilibrium is a moral theory (or, in 1951, a justified moral decision).Footnote 40 For pragmatists, the epistemic and the practical purpose are equally important—knowing and agency are dialectically connected.Footnote 41 The primary purposes of moral inquiry are right action and reliable understanding. We want to determine the right action, but in order to do so, we need a reliable understanding of our situation—an understanding that we are justified to accept and on which we are justified to act. And conversely, while we want a reliable understanding, a crucial test for that understanding involves its practical effects. In addition to those two primary purposes of moral inquiry, a third purpose should be distinguished, namely self-improvement.Footnote 42

-

1

Reliable understanding. I follow Goodman and Elgin in arguing that we should seek understanding rather than knowledge.Footnote 43 Understanding is holistic, whereas knowledge usually pertains to discrete propositions.Footnote 44 This combines well with pragmatism’s holism, in which specific statements are reliable because they fit in a reliable understanding, not the other way round.Footnote 45 Understanding need not be propositional; it may also be tacit and practical: for example, when a craftsman simply knows how to do something.Footnote 46 According to Goodman and Elgin, a systematic understanding of a certain topic or domain can be captured in an account. An account is a tightly interwoven, holistic tapestry of mutually supportive commitments.Footnote 47

I use the term reliability rather than truth for three reasons. The first reason is that it makes it possible to present a view of pragmatist reflective equilibrium that remains largely neutral with regard to controversies on the meaning and the role of truth.Footnote 48 The second reason is that reliability is broader than truth; reliable accounts may contain true statements, but also fictions, metaphors, and felicitous falsehoods to which the predicate “true” may not apply.Footnote 49 The main reason, however, is that reliability more directly connects understanding to action: that is, a conviction (or set of convictions) is reliable enough to act upon. It thus connects the epistemic and the practical purposes: a reliable account, as I understand it, is an account that we are justified to accept and on which we are justified to act.

My use of reliability is in line with general usage where reliability can refer to persons, instruments, processes, and beliefs on which one can depend, because they can be trusted or function well.Footnote 50 Similarly, I suggest that reliability in reflective equilibrium may also refer to convictions, to processes of inquiry and reasoning, and to persons. However, the term also has infelicitous associations, because it is more narrowly understood in epistemology in a technical sense as referring to truth conducive processes, and is associated with reliabilism.Footnote 51 Even so, there is no better term. Goodman and Elgin (1988) use “right” understanding, whereas Elgin (2017) uses “tenable”. In my view, “right” entails infelicitous associations with the notion that there is only one right answer, whereas I advocate pluralism. Both “right” and “tenable” (as well as possible alternatives like “acceptable”) suggest that the focus is on the cognitive content, whereas for pragmatists the focus is on agency. “Reliable” is the only word that directly integrates the cognitive and the practical, in the sense that actors can depend on convictions, persons or processes that are reliable, both in reasoning processes and in action. I suggest this may be a good reason to drop the narrow epistemological interpretation of what reliability means in favor of the broader one that I advocate here.

Reliability is a gradual quality; a set of convictions can be very weakly reliable, but become more reliable during the reflective equilibrium process. We should aim at a higher degree of reliability but not at certainty. As anti-foundationalists, pragmatists hold that certainty is not to be had, because there are no indubitable foundations.Footnote 52 Our statements and our accounts can merely be contingently or provisionally reliable. We may not imagine now how they could be falsified or otherwise rejected, but we cannot claim absolute or universal necessity. Even so, that may be good enough.

Increasing the reliability of our understanding is a gradual process of piecemeal reconstruction, but not in the simple incrementalistic sense that we continuously add new propositions to our current set.Footnote 53 Our understanding is not enhanced when we add a largely irrelevant proposition or a proposition that merely confirms what we already believed. Our understanding is improved, however, when it becomes richer, more coherent and more relevant. Sometimes, adding—or skipping—propositional insights contributes to this. Sometimes, we should read literary fiction, listen to people whose backgrounds are different from our own, watch movies and documentaries, or acquire new experiences. Some people may want to add the perspective of an exemplary person by asking, for example, what Jesus—or Gandhi—would do. Abstract ideal theory, devices like an original position or an impartial observer, may also play a heuristic role in a pragmatist approach by providing a perspective that is different from our own. In the end, the question is whether each of these means enriches our understanding, and whether our account has been adequately tested to be relied upon for our actions. There is no absolute endpoint of moral inquiry. We can always aim at a better understanding. Even so, we can stop our inquiry, for now, if we have constructed a provisional account that is “as good as any available alternative”, and we cannot see how further inquiry might improve it.Footnote 54

-

2.

Right action.Footnote 55 Questions about how we should act may concern individual actions such as: how can I in my personal life fight climate change? They can also focus on government action, for example: which policy is best to fight climate change? And they can have a legal character: for example: which statutes will effectively fight climate change? Sometimes, these are binary choices of right and wrong, but often the problems are complex, and we can only hope to improve the quality of our actions, policies, and regulations. Humans are fallible, but we can at least try to avoid wrong actions, and aim to act as good as we can.

-

3.

Self-improvement. There are three aspects of the self at stake here, relating to intellect, perception, and agency.Footnote 56 A reflective equilibrium process may lead to improving our intellectual faculties by exercising our rational skills. Apart from teaching contexts, this is usually more a side effect than an explicit purpose. However, rational skills are not enough. According to Michael DePaul, reflective equilibrium theory is overly intellectualist.Footnote 57 It focuses on beliefs but the inquirer is neglected.Footnote 58 Inquirers also need perceptive skills: that is, being able to make fine distinctions, to perceive a situation as having a certain moral quality, and so on. DePaul argues that we should train and enrich our moral perceptive skills, our capacity for making sensitive moral judgments, in order to improve our judgments.Footnote 59 The process of reflective equilibrium may help to improve our perceptive skills, for example, if we broaden it to include the formative effects of reading literature or having practical experiences that will broaden our minds and sometimes radically change not only our beliefs but also ourselves. For DePaul, the improvement of our perceptive faculties is instrumental regarding the epistemic goal of moral inquiry, but I submit that we can also regard it as valuable in itself. Finally, moral inquiry may improve our practical agency, our motivations. For example, a result of reflective equilibrium can be that John revises his racist prejudices, and understands that they are wrong, which might lessen his feelings of hatred with regard to Black people. He may start interacting in a more open and friendly way with his Black colleague and, as a result of that interaction, he may develop a disposition to act rightly towards Black people in general.

Perhaps it seems odd to include self-improvement as a third purpose. For some people, moral reflection leads to better understanding and right action, but the fact that they themselves may change during the process is not a purpose in itself. For virtue theorists and for some religious traditions, ideals of self-improvement are central to the good life. Therefore, we should recognize it as a possible purpose of the process. Even so, self-improvement will often only be an auxiliary purpose or a felicitous side effect. Concrete projects of inquiry usually focus on right action and reliable understanding. For example, when academic researchers study the regulation of euthanasia, the main purpose is a reliable account. This can be operationalized into the practical purpose of a normative theory on how to regulate euthanasia in a specific country.

Right action, reliable understanding, and self-improvement are in a dialectical relationship. Reliable understanding can be the basis for right action. Conversely, our actions and their consequences can be an opportunity for testing and improving our understanding and our faculties, as in experiments and in learning to master a certain skill. Therefore, understanding is both a purpose in its own right and a means to realize the purpose of right action. In order to improve our understanding, we may need to improve our intellectual and perceptive faculties as we learn to make better analyses and arguments as well as finer discernments. And it will also improve our practical virtues, as we will be more motivated to act according to our understanding.

These three purposes are quite abstract and general. For research projects, they should be made more concrete and more specific.Footnote 60 For example, our purpose can focus on concrete decisions, such as whether to perform a certain animal experiment or to pass a bill on animal experiments. The purpose can also be to construct a normative theory for a specific domain in a specific context such as the inquirer’s own country. How we formulate the purpose precisely depends on the context. Sometimes a moral decision is merely an isolated decision, while at other times it sets a precedent, and therefore we need to reflect more extensively on many similar cases. Reflective equilibrium can also be a means to structure a discussion process in an ethics committee or in other dialogical settings.

I will leave all these variations aside, but not because they are not relevant. On the contrary, each of them may lead to a different type of reflective equilibrium, to different selections of which convictions to include in the process, and to different methods to correct for our biases and errors. However, it is simply impossible to discuss all these variations here, let alone the precise implications of each of them for the design of the inquiry process. The most important lesson, however, is that if we design a reflective equilibrium methodology for a specific inquiry, we must first determine in detail what precisely the purposes are.

4 Initial convictions or commitments

Largely equivalent terms that may be used instead of convictions are judgments (Rawls 1951, 1971/1999), considerations (Rawls, 1971/1999, p. 19), commitments (Brun, 2013, p. 240; Rechnitzer, 2022, pp. 22–23) or simply beliefs. I will mostly use convictions because it emphasizes the contents of what we hold; sometimes I will use the term commitment to emphasize the relation between agents and their convictions. I reject the use of intuitions that is also frequently used in the literature, for a convincing critique on intuitions, see Brun (2013).

Methods of inquiry have the double function of identifying what is reliable and guarding against bias and error. For example, accepted methods of data collection and statistical analysis are designed to provide highly reliable data and to avoid common causes of bias and error. We can achieve this by means of preventive measures in our research design, but also by applying critical methods that allow for correction and revision. Methods of moral inquiry should help us to identify the most reliable moral convictions and improve the reliability of our set of convictions, as well as to prevent and correct error and bias. These methods and their outcomes must also be feasible. A method that only can be applied by a Hercules or an ideal observer is not feasible, nor is a method acceptable if it leads to norms that are psychologically unrealistic. Thus, there are three issues that should be addressed in a methodology of moral inquiry:

-

1.

How can we increase the reliability of the process and the outcome?

-

2.

How can we prevent bias and error, and how can we correct them?

-

3.

Are the process and the result feasible?

In this and the next section, I will discuss which convictions to include in the reflective equilibrium process; in Sects. 6 and 7 methods for critical scrutiny. These three questions will be central to my examinations of those issues.

Norman Daniels famously argued that reflective equilibrium is the “process of bringing to bear the broadest evidence and critical scrutiny.”Footnote 62 However, this is not what Rawls or Daniels actually do. Rawls brackets or completely excludes concrete empirical knowledge, personal commitments and comprehensive views of life. Moreover, both in 1951 and 1971, he excludes the less certain of our initial moral convictions, and merely uses a subset of convictions, the considered judgments.Footnote 63 This choice may be understandable in an epistemic project. If the aim is a universal theory, starting with highly uncertain convictions is not likely to deliver certainty.

A pragmatist approach takes a different view. It uses all initial convictions, even the dubious and weakly reliable ones—although for convenience, it may begin with a selection. It would be artificial not to include them all. They are our convictions and—even if weakly—we are committed to them.Footnote 64 If we exclude some from the equilibrium process, they will not miraculously disappear from our mind. We will still somehow believe in them, and they will implicitly or subconsciously influence our understanding and our actions.Footnote 65

Let us take a fresh look. Pragmatism is holistic.Footnote 66 Our set of empirical convictions as a whole seems initially reliable, because while relying on that set, we manage to live in the world and to act effectively. For practical purposes, most of the empirical convictions of a well-educated person are initially reliable. Of course, we also have superstitious, unfounded and mutually inconsistent beliefs, and some generally accepted theories may be incorrect, but we cannot tell which beliefs and theories are incorrect. Therefore, we need methods to continuously test, criticize, and revise some of our convictions. As a whole, however, our set of empirical convictions serves us reasonably well and may be considered initially reliable. My claim is a minimal one and may easily be misunderstood. A reliable account, as I defined it, is one that we are justified to accept and on which we are justified to act—in our specific circumstances. In some circumstances, we simply do not have the time to critically reflect on our convictions; then the weakly reliable set of initial convictions is all that we have. Often we cannot avoid acting, and we must make a decision. My claim is merely that in such situations it is better to rely on our set of initial convictions than to toss a coin. I believe that most inquirers would agree that our initial set of convictions is weakly reliable in this minimal sense, both for epistemic and for practical purposes. Even so, reliability is a gradual concept, and if we have time for further, we should try to increase the degree of reliability of our set of convictions. That is where reflective equilibrium can help.

Perhaps then it is different for moral convictions? They frequently give rise to controversy, and we may seriously doubt some of them. Nevertheless, our societies function reasonably well as the result of moral prohibitions with regard to killing, stealing, and lying, especially if they are legally enforced; we do not have a Hobbesian war of all against all. The primary cause of serious crime is not that our society has too many epistemically dubious moral and legal norms—it is that some people do not follow the norms. Obviously, we are uncertain or divided with regard to some issues: for example, those concerning animals, nature and future generations, and regarding sexuality and bioethics. Our societies still harbor many sexist, homophobic and racist prejudices, and are far from just. Even so, uncertainty and controversy with regard to some normative convictions does not justify wholesale skepticism. It only means that we should develop methods to test and criticize our initial convictions, especially in those fields where we feel less certain or where controversy is strong. We should acknowledge that there are degrees of reliability and that some convictions that we hold are only weakly reliable and even dubious.

Therefore, our set of moral convictions as a whole is also initially reliable, even if less reliable than the set of empirical convictions. This claim of weak reliability is supported by the fact that our convictions are usually embedded in a tradition.Footnote 67 Most of our norms have been developed and tested in our community. Our moral norms have largely worked well for our parents, and so there is an initial plausibility that as a whole they might work well for us. But obviously we must be cautious. Some of our parents’ convictions may be in need of revision, especially in those areas where technology or society has changed substantively. Several convictions may be the result of dominant ideologies that have been internalized, or of substantive prejudice. And some of them may really be outrageous, such as traditional racist, sexist and homophobic norms. Again, although this should make us very cautious, it is no ground for wholesale skepticism.

Our conclusion can be that the initial set of convictions is as a whole weakly reliable, and therefore is a good start for moral inquiry.Footnote 68 However, some convictions—and we do not know which—may be unreliable, and therefore we need methods to criticize, test and revise them. This holds true both for empirical and for moral convictions. Rawls’ set of considered judgments has probably a higher degree of initial reliability than the full set of initial convictions; therefore, the need for critical revision is higher in a pragmatist approach. Nevertheless, from the perspective of initial reliability, it is justified to start with the full set of initial convictions.

From the perspective of feasibility, we should also use the full set rather than only a subset. The ultimate aim of moral inquiry is action. It is we who must act—on the basis of our own understanding and our own actual motivations. We cannot act on the imagined understanding that competent judges or personst in the original position would have, simply because their convictions and their motivations are not ours. If in the reflective equilibrium process we were to ignore some of our initial convictions because they seem dubious, we would still have those commitments and the associated motivations after the process. Therefore, they would still influence not only our motivations but also our actions. If we exclude religious views on homosexuality from the reflective process, this means they are not subjected to critical scrutiny and they will remain unchanged. Such convictions do not simply disappear from our mind. Because they are not subjected to testing and criticism, they are immune to revision. Consequently, these convictions still influence our actions. Only if we include all initial convictions in the process of mutual adjustment can we criticize and revise them, explicitly discard the dubious ones at the cognitive level, but also at the motivational level, and can we reasonably expect our actions to reflect the resulting account.Footnote 69 It is not just our cognitive accounts that change during the reflective equilibrium process but also our emotions, attitudes, and motivations The equilibrium process results not only in a revised rational account but also in altered motivations and dispositions. Consequently, the gap between what we deem is right to do, what we are motivated to do, and how we act may be reduced.

5 Facts, comprehensive views and personal commitments

Persons in the original position only possess knowledge of general facts and background theories; they do not have comprehensive views of life nor personal commitments and other personal characteristics. Again, these exclusions are understandable in an epistemic project aiming at universal theories. However, the restrictions come at a price. Personal relations and social commitments are important both for the content of moral convictions and for motivations to act.Footnote 70 Comprehensive views of life are strongly connected to moral commitments and motivations. And facts are not merely a context of application of general principles; they are crucial for fully understanding concrete problems and normative convictions.Footnote 71 The Rawlsian framework is not merely overly intellectualist; it also excludes some of the most relevant elements with regard to actions.

Pragmatism is holistic. Therefore, it rejects the exclusion of certain categories of convictions. It is contextual, so we should include all relevant facts. Moreover, our comprehensive views of life and religious commitments may influence our convictions and our actions; therefore, they must be subject to critical scrutiny rather than be excluded during the equilibrium process, only to emerge again later on. This is similar to the point made in the previous section with regard to excluding some dubious initial convictions. If we exclude from critical scrutiny all religious views as well as those commitments that are most dear to us—for example, to our family and friends—we leave out elements that are central to moral motivation and we will miss opportunities to scrutinize these motivations and improve ourselves. The likely result is that in the end we do not act according to our intellectual convictions but according to those initial personal commitments.

A moral inquiry usually begins with the construction of an elementary, provisional account. This is a narrow reflective equilibrium, based on both general and concrete initial moral convictions and on relevant facts and social theories. The reason for including facts and social theories is that we must act in a specific context rather than in some ideal world. Moreover, morally relevant facts may also have both sui generis and general moral salience.Footnote 72 Even so, including everything is impossible. A good practical restriction is often to begin with a limited domain of inquiry, and then start with only a subset of our initial moral convictions: for example, those of which we are strongly convinced. The reason for this restriction is not, as with considered judgments, that they provide certainty, but that including all convictions in the initial equilibrium process would make it too complex. We may also decide to use starting points different from our own initial convictions. For instance, we could use the moral convictions of nurses and physicians as input for an analysis of patient autonomy in nursing homes.Footnote 73

All relevant convictions should be on the table—but not all at the same time. If we restrict our initial set of convictions, we should include the excluded convictions in the process at a later stage. We should gradually add more convictions, such as comprehensive views, additional facts, and moral principles that seem valid for other domains. We should especially add moral dilemmas and problematic cases to test and refine our set of convictions. Which convictions to include is a matter of convenience and relevance. It is a pragmatic balance: When can we reasonably expect the costs of adding more convictions to be higher than the gains in terms of improved understanding?There is no meta-rule or standard on how to strike this balance. Experienced inquirers will often encounter a saturation point where they can reasonably expect that adding more convictions simply will no longer change their equilibrium, or at least not significantly.

Obviously, the broadly inclusive pragmatist approach advocated here has one major disadvantage. It includes all kinds of biases and errors, resulting from comprehensive views, self-interest, and personal commitments. The remedy is to put maximum effort into methods for critical scrutiny.

6 Coherence

The set of initial convictions is only weakly reliable. We know many convictions are unreliable, but we do not know which. Therefore, a reflective equilibrium process must include methods for critical scrutiny. One core method is to make the set more coherent. In this section, the central question is what role coherence plays in pragmatist reflective equilibrium. Coherence consists of at least three criteria: consistency, mutual support, and comprehensiveness.Footnote 74

Why is coherence important? A familiar argument is that we can deduce anything from an inconsistent set of statements. However, this argument is unconvincing. John Rawls argues that the state of reflective equilibrium is an ideal that we often cannot reach.Footnote 75 Consequently, the resulting theories will frequently, if not always, be incoherent and even inconsistent. If the aim were to deduce formal theories more geometrico, this would be a serious problem. But moral theories are not like that. For example, my current convictions with regard to animal ethics are in flux and inconsistent. From this inconsistent set of convictions, it is logically possible to deduce anything: for example, the statement that killing humans is not wrong. But I do not do that, because it makes no sense to deduce such statements with purely formal reasoning. My incoherence with regard to animal ethics is practically irrelevant to my norms with regard to murder.

In a view in which theories are formal and self-contained, any incoherence may be fatal. In a pragmatist approach, in which theory is embedded in a broader understanding and connected to practice, it is not. We just should find ways to deal with it. Sometimes we can remove incoherence through logic and practical tests. Or we may conclude that one position has the best arguments. We can also confine the incoherence for the time being to one domain, and accept that there is a multiplicity of defensible positions. My conclusion is that the purely logical argument for coherence does not work in moral inquiry. I It proves too much: namely, that almost all our theories are incoherent and therefore invalid. Moreover, it is unrealistic, as we can often handle some degree of incoherence quite well.

A second familiar argument is that coherence is evidence of truth or justification, or even constitutive of truth.Footnote 76 In a pragmatist approach, coherence plays a different, more modest role. It is a means to test and revise our convictions and to increase the reliability of our set of convictions. Coherence is a gradual concept, and full coherence will hardly ever be attained. Therefore, some degree of incoherence is never fatal, but merely an indication that we have not been able to fully justify our accounts. For the time being, however, a provisional and partly incoherent result may be good enough.

In light of the three general purposes of moral inquiry, a pragmatist approach focuses on different arguments for coherence. Incoherence makes our accounts less reliable, it reduces practical efficacy and it conflicts with personal integrity.

Less coherence leads to less reliable accounts with regard to all three dimensions of coherence distinguished above: consistency, mutual support and comprehensiveness. First, inconsistencies between conflicting convictions are reasons to question the reliability of these convictions. When the inconsistencies are resolved, the account becomes more reliable. Second, mutual support is important, because additional support for some of our convictions increases their reliability. Moreover, mutual support usually requires that we refer to general principles that can explain and justify the reasons for accepting concrete convictions.Footnote 77 When mutual support becomes stronger, the reliability of both our individual convictions and the account as a whole increases, and the reliability of new convictions embedded in our account also increases. Third, comprehensiveness requires that we attempt to broaden the domain of application, and include cases of which we were uncertain or that may arise in the future. An account of democracy based only on nation states becomes more sophisticated when we test and refine it in light of new contexts like the European Union and universities. The broader the domain and the broader the set of convictions included in my account, the more reliable the account.

The second reason that pragmatism values coherence is practical efficacy.Footnote 78 We simply cannot decide all our actions case by case; efficient action requires general rules and principles.Footnote 79 We can only rely on rules and principles if they are part of a coherent account. Otherwise there will be too many cases where the arguments go both ways. Therefore, a coherent account is necessary for efficient agency. Moreover, if my account is incoherent, my actions may undermine each other. The more coherent my account, the more effective my actions, because my actions will reinforce rather than undermine each other.

The third reason to value coherence is the ideal of personal integrity. Integrity requires that we are persons who act on intellectually coherent convictions, rather than having a different stance every day. This is more than consistency, although consistency is part of it. For example, we would criticize someone who is a vegetarian on weekdays because she is categorically against killing animals, but happily eats meat during the weekends. That position could be consistent with the aim of reducing environmental impact (by eating less meat) but not with the principle that killing animals is wrong. Comprehensiveness is also relevant for integrity. Some politicians defend an absolute prohibition of killing with regard to abortion and euthanasia; we may question their intellectual integrity if they refuse to reflect on whether the general principles behind this prohibition might be relevant to the death penalty as well.

Each of these three arguments explains why coherence is good, but none of them implies that full coherence is necessary. On the contrary, incoherence may be the herald of intellectual and practical innovation and an indication of responsive perception. The combination of a wave model and a particle model initially made theories of the electron incoherent, yet it was a necessary step to better understand it. The current inclusion of animals, the environment, and future generations in so far largely anthropocentric political theories makes them initially less coherent. Categorically asking for coherence may therefore have a conservative methodological impact.Footnote 80 Coherence is for pragmatists an important regulative ideal, but it is not always possible to fully realize it—nor is it always desirable.

If two convictions are incoherent, we should determine which one to revise. However, there is no general principle regarding which one. We must search for reasons why we believe a specific conviction has to yield.Footnote 81 Perhaps we got it from hearsay or an unreliable internet source, or we may come to understand that a prejudice is the result of our upbringing. Or we might consider that a principle is too generally formulated, and we should make an exception because we feel strongly that in this exceptional case the principle does not apply. In the end, however, there is an irreducible subjective component.Footnote 82 What to me seems a convincing argument to revise a conviction may not appear convincing to you. The fact that you are not convinced should give me an additional reason to pause and subject my reasons to critical scrutiny. Reflective equilibrium does not always provide uniquely right answersFootnote 83 what we may hope for is that it frequently does and that in other cases it at least reduces the number of defensible alternatives. Sometimes, we may not find good reasons to skip one of the conflicting convictions, for example, because we are deeply ambivalent. The provisional result of our inquiry could then be the clarification of that ambivalence rather than a coherent account.

7 Other methods of critical scrutiny

Increasing the coherence of our accounts is only a minimal form of critical scrutiny. It is not enough to correct for all sources of bias and error, especially not if they have a more systematic character. Moreover, we should aspire to transcend the limitations of our current understanding, and allow for creativity and innovation. Therefore, we need additional methods in order to guarantee maximum critical scrutiny and maximum creative input.

Rawls’ notion of the original position is a methodological device to facilitate strict argumentation, just like his 1951 notion of competent judges and the 1993 notion of political reflective equilibrium. Pragmatists do not have such strict methods. There is not one general pragmatist methodology. The methods we should choose depend on the purposes, context and practical possibilities. This is no different for moral inquiry than for empirical investigations. The police investigate a murder case more extensively than a minor traffic incident. When the possible penalty is a life sentence, the empirical basis must be more reliable than for a 100 euro speeding ticket.

Moral inquiry must find a compromise between the three issues identified at the beginning of Sect. 4. On the one hand, we should increase the reliability of our convictions and correct bias and error, but on the other hand, the methods should be feasible. We cannot examine all possibly relevant facts, theories, moral convictions, and perspectives. Therefore, we must reduce the complexity in order to make moral inquiry workable. We should try to determine the most important risks of bias and error in the specific context of our inquiry.Footnote 84 If we study discrimination, we must include the most relevant perspectives on discrimination. If we study economic distribution, Rawls’ focus on the worst off might be a good starting-point. Even so, we should have a pluralistic understanding of who those people are. Low income and poverty are reasons to consider some people worst off, but various other groups may also qualify, such as single-parent households or persons with disabilities. Depending on the biases we identify, different methodological devices may be required. This variability of purposes, contexts, risks and practical possibilities is the reason why we cannot construct one general methodology of reflective equilibrium.

Whatever the starting points with regard to a subset of initial convictions, we should critically revise and enrich this subset in order to address the conservative bias and to correct bias and error. There are many ways to do so, and the methods one chooses depend on the characteristics of a specific inquiry.Footnote 85 The methods can be grouped in three clusters that may focus on 1. Adding specific types of convictions; 2. Adding new perspectives and 3. Transforming ourselves.Footnote 86

7.1 Adding convictions

A crucial method is to reflect on those convictions about which we felt uncertain. If we find that they might have been influenced by lack of rationality, self-centered bias, prejudice, or other errors, as well as that they conflict with the provisional equilibrium, we should discard them altogether so that they no longer—subconsciously—influence our decision making. However, for some questionable initial convictions, the uncertainty is associated with emergent changes in our views. To take a simplified example, many people in Western societies are ambivalent with regard to eating meat.Footnote 87 If ambivalence is the reason for moral uncertainty, rather than excluding these ambivalent convictions we should pay special attention to them. They may be the starting point for a more radical revision of our views with regard to the treatment of animals. Uncertainty and ambivalence may be the herald of a more fundamental moral change. Explicitly searching for this kind of uncertainty and ambivalence may be a good strategy for critical scrutiny.

A second method can be to deliberately search for new convictions. An important potential for challenge, criticism, and change can be found in novel cases and our initial responses to them. These may be science fiction cases or fictional cases that abound in philosophy, like the trolley case. Sometimes it is a real-life case that shocks us. This can be a dramatic one, like the well-known pictures of the Syrian refugee father holding his drowned son in his arms. But they can also be more ordinary. The experience of living next door to a friendly gay family may make people reconsider their views on homosexuality. Perhaps the most important way to broaden one’s horizon is simply to listen to other people’s views and experiences, especially if they are different from our own.

These new cases and convictions may disturb our provisional equilibrium and make it more incoherent. One way to accommodate them and revise the equilibrium is by paying special attention to one specific subclass of our convictions: namely, ideals. Ideals have a surplus of meaning; they can never be completely formulated.Footnote 88 The ideal of democracy has partly been elaborated in domestic state legal orders, but it cannot be reduced to that. Democracy is also relevant for universities, but the implementation cannot simply copy the state order. For example, the notion of ‘one man, one vote’ cannot be applied to a university, because students would always overrule professors. Ideas like checks and balances, and open debate on the merits of proposals, however, may be valuable for designing university democracy. Reflecting on ideals in light of new cases and our initial responses to them may change our understanding of the interpretations of those ideals, and it may help to revise principles and rules so that they can account for our initial responses. In this manner, the interplay between novel cases and ideals may put the provisional equilibrium under scrutiny and offer new insights.

7.2 Adding theoretical perspectives

A second cluster of methods to criticize and expand a provisional narrow equilibrium involves looking at it from alternative and critical perspectives or frames, even if they are not our own.Footnote 89 One need not be a Marxist or a feminist to be enriched by Marxist and feminist analyses. They may provide additional convictions or critiques of our own convictions. This can include all kinds of critical theories, such as critical race theory or queer theory. We may also explore a deontological approach if our own view is predominantly utilitarian or vice versa.Footnote 90 Any method that can help us to get outside the box and apply a fresh perspective may help. That does not mean we must always study all these perspectives. We should explore the most likely biases with regard to specific problems and then decide how to deal with them. If we study adoption, queer perspectives may be more important than Marxist ones. If we analyze economic justice, the reverse may hold.

7.3 Transforming ourselves

A third cluster of methods focuses on transforming ourselves as inquirers and actors. According to DePaul, to improve our faculty of moral judgment we should seek out new formative experiences.Footnote 91 We can do so in different ways. Reading literature is one approach. Albert Camus’ The Plague may help us to better understand how deadly plagues can transform human society. Watching movies and documentaries, reading science fiction, meeting people with backgrounds different from our own, and having personal contacts may all lead to formative experiences. Religious experiences, or working in a poor neighborhood or a refugee camp, may actually be life transforming. A historical example is the strong support for prison reform in the Netherlands after many societal leaders had been imprisoned during WW II and were shocked by their experiences.Footnote 92 Such formative experiences enrich and change our perceptive faculties, bring a fresh perspective on our set of convictions, and will often lead to substantive revisions of our views.

8 Objections and advantages

In the introduction, I suggested that in a pragmatist perspective many critiques against reflective equilibrium are invalid or can even be seen as advantages. Obviously, the critique on a Kantian or rationalist bias is no longer applicable, because the Kantian elements have been skipped. The critique on the individualistic and liberal bias can be countered by the more inclusive process, which includes personal commitments and allows for dialogical processes.

Indeed, in a pragmatist perspective, there is room for actual dialogue and democratic participation, and therefore for variation in light of specific political and moral traditions. Although, for reasons of simplicity, the focus in this article has been on individual inquiry, reflective equilibrium can also be used in dialogical and social contexts: for example, as a model for structuring interdisciplinary collaboration,Footnote 93 public debates, and ethics committees.Footnote 94 It can also include the opinions of professionals and ordinary citizens.Footnote 95 In many philosophical theories, including Rawls’ A Theory of Justice, there is little opportunity for ordinary citizens to influence the design of political institutions. One philosopher can do all the work, and if she has done her work well, ordinary people and fellow philosophers merely need to assent and accept it.Footnote 96 The Rawlsian four-stage sequence presupposes that basic institutions and constitutions can be designed by a philosopher without input from citizens.Footnote 97 Only at the last stage, the level of concrete political decisions, is the veil of ignorance fully lifted so as to include views of actual citizens. This seems strange. Should we not take into account the views of citizens on what constitutes the best institutions? Many philosophical traditions do not leave much room for that. Pragmatism does.

The objection that reflective equilibrium does not lead to universal theories, truth, or certainty must, however, be accepted as justified. Our convictions can only be provisionally reliable. For pragmatists, though, this is no objection; it is merely the consequence of the fallibility of human inquiry.Footnote 98 Full certainty is simply not to be had. Practical reasoning is not the application of universally true principles or rules, but is a dialectical process between our understanding and our actions in specific contexts. Therefore, a pragmatist approach can do more justice to variations in contexts. It is proudly pluralist and proudly dynamic: different situations and different contexts require different understandings and different moral actions. An advantage of focusing on context-sensitive understanding rather than on universal moral truths and ideal theory is that our account includes case-specific details, and we do not need a further series of often quite arbitrary steps in which general principles are applied to concrete cases.

The pragmatist understanding of reflective equilibrium advocated here may raise new objections. One objection is that I have diverged too much from Rawls. This would not be an objection to my project as my aim was not to reconstruct Rawls’ theory, but to develop a pragmatist approach to reflective equilibrium. Even so, I submit that my reconstruction is still in line with the basic idea of reflective equilibrium as developed by Rawls—and with that of Goodman and Elgin.Footnote 99 The basic ideas remain the same: we should collect all relevant considerations; we should revise and refine them in a dialectical process aiming at coherence; and we need methods to counter bias and error. In fact, Rawls’ claim that we should include a broad set of considerations is even better realized in the pragmatist version than in the Rawlsian one, as it does not exclude any considerations from the process. The notions of the original position and competent judges are not completely rejected; they can still play a modest role. Rather than choosing one method as if one size fits all, pragmatism takes a context-sensitive, pluralist approach to methods. Methodological triangulation is possible. We may use the original position as one method to think about justice, and an impartial spectator, hypothetical auctions, or spaceships as alternative methods. The heuristic insights of each approach may be confronted with each other, and thus enrich and refine our understanding.

A second possible objection is that, because it lacks strictness, this version of reflective equilibrium is no method and no methodology.Footnote 100 If one takes a narrow view of methodology as a standard procedure that leads to the same, replicable result regardless of the person who follows the procedure, it is not – but neither is Rawls’ version. Reflective equilibrium has an inevitable subjective component, and it is methodologically and substantively pluralist. There is not just one standard procedure of reflective equilibrium to reach a reliable account: in fact, many methods can be used and they can complement and correct each other. However, in a broader view, reflective equilibrium may be regarded as a methodology.Footnote 101 Or more precisely, it may be seen as a general methodological approach that can be operationalized in a context-sensitive way into specific methodologies. Like ‘quantitative research’ or ‘participatory observation’, it is an umbrella term. There is a clear core idea of collecting all relevant considerations and testing and refining them through a dialectical process of critical scrutiny. There are various methods to criticize and improve the provisional reflective equilibrium at the start of the process. Therefore, it is a distinct methodological approach—even if a pluralist one.

9 Conclusions

In this article, I have argued that we should reconstruct reflective equilibrium in a consistently pragmatist way. Rather than trying to develop a full framework, I focused on some central issues. I discussed the implications of a pragmatist approach to moral inquiry for the purposes and for some core elements of reflective equilibrium. I have argued that this pragmatist approach is the best way to defend reflective equilibrium against various criticisms, partly by embracing the critiques as advantages.

In the introduction, I noted two problems: the continuing critiques and the lack of methodological guidance. I have not solved the latter problem. Pragmatism is context sensitive and pluralist, which implies that we can only elaborate the general idea of reflective equilibrium into a variety of more concrete methodologies in light of our purposes and possibilities. Even so, the article clarifies the issues that we should address in developing concrete methods.

This article has focused on presenting a pragmatist approach to reflective equilibrium, but it has not defended pragmatism as such. Even so, we should note one big difference between Rawls’ version and the pragmatist one. The first is primarily an epistemic project, with the rational inquirer at the center of the equilibrium process. Pragmatism puts agency at the center, which comprises both actors and actions. We are not persons in the original position or competent judges. Rationality is an important characteristic of agents, but it is not all. Pragmatist reflective equilibrium involves full agents—with their emotions, personal commitments, and comprehensive views—in the concrete contexts in which they mustact. As a result of this broad inclusiveness, it is more likely that agents will also act on the basis of the account resulting from the reflective equilibrium process. This is an important difference between the two versions. Moreover, it is also an important argument in favor of the pragmatist version.

Notes

An influential example is Beauchamp and Childress (2013).

Rawls (1971/1999, pp. xviii and 221–227).

I will therefore try to ignore controversies about concepts like rationality, knowledge and experience, on which pragmatists differ among themselves. The version of reflective equilibrium that I present here does not depend on taking specific stances in these debates and consequently is as neutral as possible.

Legg and Hookway (2019).

Luban (1994, p.134ff). The other characteristics are anti-essentialism, experimentalism, conventionalism, biologism, and historicism.

Luban adds rationality as also being context specific, but I leave that point aside, as my aim here is to develop reflective equilibrium without presupposing specific views on rationality.

Cf. James (1907/1992, p. 45).

Botti (2019, p. 97) notes that in Rawls’ personal copy of Quine’s book From a Logical Point of View, presumably read in 1955, Rawls underlined the passage on pages 78–79 referring to Neurath’s metaphor and circled Neurath’s name.

Cf. Misak (2000, p. 95) “The pragmatist takes correct judgement not to be a matter for the individual, even though it is the individual who does the judging, but as a matter for the community of inquirers. (…)”.

Therefore, when I use the word pragmatism in this article, it should be understood as Deweyan pragmatism.

Pragmatism rejects strict separations between facts and norms. In my view, therefore, moral inquiry is not separated from non-moral inquiry, and it will usually require substantive empirical inquiry as part of the analysis.

A core difference between the latter and me is that I discern three co-equal purposes for a reflective equilibrium process whereas Elgin focuses on the epistemic purpose of a justified account. See Sect. 3 below. This broader understanding of the purposes has implications for the various other elements that I discuss in Sects. 4 through 7.

For example, I hardly discuss theoretical virtues (Rechnitzer, 2022, pp. 31–32) except for coherence, or the various subcategories of beliefs or convictions, such as principles, facts, considered judgments, background theories and ideals (Van der Burg & Van Willigenburg, 1998b, Part One), nor do I provide an integrated account of all steps to be made in a full equilibrium process.

Most of these were collected in Daniels (1996).

Goodman (1955) did not use the term, but suggested we can justify rules of inductive and deductive logic by confronting them with acceptable cases of inferences. For more elaborate versions, see Goodman and Elgin (1988), Elgin (1996, 2017). Until recently, it was widely believed that Rawls derived the idea from Goodman. However, Botti (2019), Chapter 5 has shown that the young Rawls developed his ideas about moral inquiry a decade before Goodman’s book, especially in the context of a seminar on induction at Cornell that he attended in 1947–1948.

For variations in contexts such as public debates, committee meetings, applied research and Socratic dialogue, see various contributions to Van der Burg and Van Willigenburg (1998b).

Rawls does not use the phrase “reflective equilibrium” in 1951. However, he states in Rawls (1971/1999, xxi) that, with some modifications, he follows the point of view described in his 1951 article; therefore, it can be regarded as a not yet fully developed version of reflective equilibrium.

For the central role of induction in the younger Rawls, see Botti (2019, Chap. 5) entitled ‘Induction and the Origins of Reflective Equilibrium’.

Rawls (1971/1999, p. 8).

The original position is partly justified through an independent reflective equilibrium process, based on a separate subset of considered judgments and background theories. So there are at least two reflective equilibria in 1971; a methodological one and a substantive one. See Daniels (1996, esp. 23 and 61), on the independence constraint that the considered judgements in both equilibrium processes must be to a significant extent disjoint. This is, in my view, one of the core Kantian elements in Rawls that should be rejected because it requires an artificial distinction or even separation between the methodological and substantive elements which in a holistic perspective cannot be upheld.

Rawls (1971/1999, pp. 18n7 and 507n34) respectively.

Individuals in the original positions will derive their conclusions by “strictly deductive reasoning” (Rawls, 1971/1999, p. 103). On p. 105, he argues that “we should strive for a kind of moral geometry with all the rigor which this name connotes.” Even though his reasoning “falls far short of this,” it is essential to have this ideal in mind.

I will henceforth use “bias and error” to refer to all possibilities of mistake, bias, prejudice, lack of rationality, self-interested partiality, and so on. Rawls mentions various causes such as principles tailored to the circumstances of one’s own case, particular inclinations and aspirations and persons’ conceptions of their good (Rawls, 1971/1999, pp. 16–17).

For an overview of the criticisms, see the literature mentioned in footnote 2 above.

Even so, if I understand him correctly, this is largely what Hübner (2017) tries to do. He considers the 1951 and 1993 versions of reflective equilibrium as mistaken, and suggests that the 1971 contractualist framework including the thought experiment and the reliance on rational choice theory provides a necessary ‘scaffold’. He thus downplays the coherentist elements in 1971 (and in the two other versions) and makes reflective equilibrium part of a semi-foundationalist project which, in my view, does not merely interpret Rawls incorrectly but is also untenable. For a critique of semi-foundationalist understandings of reflective equilibrium see Van der Burg (2003).

Norman (1998).

Tersman (1993, p. 29) argues that Rawls shifts from epistemic justification in 1951 to practical justification in his later work. I would suggest instead that Rawls’ project has always included a mix of both epistemic and practical aims, and that although there are variations in emphasis throughout his work, his major concern has remained that of epistemic justification.

Cf. for this dialectic, Dewey (1929/1960, p. 37): “Constant and effective interaction of knowledge and practice is something quite different from an exaltation of activity for its own sake”.

Elgin (2017, p. 14).

Misak (2000, p. 86).

For an analysis of understanding, see Elgin (2017, Chaps. 3 and 4).

Elgin (2017, p. 36).

Pragmatists like Peirce, Dewey, James, Rorty, Goodman & Elgin, and Misak have all suggested different theories of truth. For an overview, see Legg and Hookway (2019). According to Botti (2019, p. 141) “Rawls never engaged systematically with the concept of truth because doing so would have conveyed the notion that he was grounding his theory on it”.

Elgin (2017).

Merriam Webster define it as: “suitable or fit to be relied on: dependable” (https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/reliable).

This objection was made by various reviewers.

Elgin (2017, p. 88).

The right action is the ultimate purpose here, but moral inquiry often focuses on an intermediate purpose: judgments about the right action.

I focus here on individuals, but self-improvement can also refer to collectives, like societies, groups, legal orders or deliberative institutions.

DePaul (1993, p. 43).

Daniels (1996, pp. 2–3).

See DePaul (1993, pp. 16–18) for additional critical arguments against Rawls’ conception of considered judgments. However, DePaul’s alternative conception still ignores the influence even our weakest commitments may have on our thinking and on our actions.

Cf. Nielsen (1993, p. 324).

One of the core issues in the literature is whether some initial convictions have independent credibility, and if so, on what basis. For a discussion see, e.g. Rechnitzer (2022, pp. 25–26 and 41–47). The holistic approach of pragmatism does accept that we may be committed more strongly to some convictions than to others, but does not rely on awarding initial credibility to individuated convictions. It merely holds that the whole set of our convictions has a weak initial credibility. The basis for this weak credibility (or in my terms weak reliability) is not a cognitive one, but a practical one: we manage to live minimally well if we rely on this set. For a similar holistic and contextualist view, see Amaya (2015, p. 478).

In the four-stage sequence (Rawls, 1971/1999, pp. 171–176), some facts and views are included in the later stages, but this sequence is one-directional, so they do not influence the initial and most importance stages of theory construction.

Van Willigenburg (1998).

Van Thiel and Van Delden (2010).

Cf. Amaya (2015, p. 355).

Cf. Amaya (2015, p. 19).

The conservative tendency is a standard objection to reflective equilibrium. It has much more force against those versions that regard coherence as a condition or requirement of truth than against the pragmatist version defended here. For a general rebuttal of this objection, see also Scanlon (2002, p. 150).

Rechnitzer (2022, p. 29).

Cf. DePaul (1993, p. 125) “Because of the individualistic character of reflective equilibrium, it is liable to lead different individuals to very different substantive moral views”.

Of course, it is difficult to diagnose and correct one’s own biases and errors. We may need others to help us do so. The social character of a pragmatist methodology and the emphasis on inquiry as a communal enterprise, may facilitate this, but is no guarantee. See Walden (2013, p. 251).

This requires a contextual and dynamic analysis. We cannot determine what methods to use independent of the project of inquiry, see Walden (2013, p. 252). Inquirers may also become aware of new biases and errors during the project, and therefore adapt their methods during the research process.

I referred earlier to Luban’s claim that pragmatism is conceptually conservative. Luban (1994, p. 139) adds that radicals are therefore at odds with pragmatism because they advocate massive conceptual revision. I disagree with Luban on the latter point. The three methods for critical scrutiny discussed in this section are all attempts to deliberately add new convictions and perspectives, and to transform ourselves so that more radical revisions become possible.

Cf. Van der Weele and Driessen (2019).

This may also provide us with new intellectual resources in the form of new concepts, words, models and metaphors. Concepts like alienation, framing, or intersectional discrimination are examples of once novel concepts that provided a different understanding of reality.

Rawls presents alternative moral theories as the options between which persons in the original position have to choose. I suggest that philosophical theories come in when a provisional equilibrium has to be critically scrutinized and enriched.

DePaul (1993, p. 173). He calls this the radical conception of reflective equilibrium, which allows for radical moral conversion. Relying on insights from feminist epistemology, Verkerk (1998) argues that transformation may sometimes require more than improving individual moral faculties: namely, a change in the self-understanding of persons. Negative views of oneself—for example, a woman feeling subordinate to her husband—may not only prevent members of oppressed groups from fully flourishing but may also negatively influence their moral faculties.

Franke (1995, pp. 244–246).

Doorn and Taebi (2018).

On public debates and ethics committees, see Brom (1998).

Cf. Rawls (1971/1999, p. 232): “The original position is so characterized that unanimity is possible; the deliberations of any one person are typical of all”.

Rawls (1971/1999, pp. 171–176).

Cf. Misak (2000, p. 45).