Abstract

Does lying require objective falsity? Given that consistency with ordinary language is a desideratum of a philosophical definition of lying, empirical evidence plays an important role. A literature review reveals that studies employing a simple question-and-response format, such as “Did the speaker lie? [Yes/No]”, favour the subjective view of lying, according to which objective falsity is not required. However, it has recently been claimed that the rate of lie attributions found in those studies is artificially inflated due to perspective taking; and that if measures are applied to avoid this problem, the results actually support the objective view of lying. This paper presents three experiments that challenge this claim by showing that the findings used to support the objective view have been misinterpreted. It is thus concluded that the folk concept of lying does not require objective falsity, which is consistent with the dominant view in the philosophical literature.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

What makes a good definition of lying? A widespread view holds that one – perhaps the most – important desideratum for a definition of lying is to capture people’s use and understanding of this concept (but see Harris, 2020).Footnote 1 Some philosophers explicitly state this aim. For instance, Carson (2010, p. 33) writes:

Lying is a concept used in everyday language, and moral questions about lying arise in people’s everyday experience. There are no compelling reasons to revise or reject the ordinary language concept of lying – at least the burden of proof rests with those who would revise or reject it. Therefore, consistency with ordinary language and people’s linguistic intuitions about what does and does not count as a lie is a desideratum of any definition of lying.

Other prominent discussants at least tacitly assume the importance of the ordinary concept of lying, which is evident when they argue for a certain definition of lying by appealing to our intuitions about (mostly) hypothetical cases (e.g. Saul, 2012; Stokke, 2016, 2018; Viebahn, 2020, 2021).

This paper concerns the question of whether the ordinary concept of lying only requires speakers to make a believed-false assertion (henceforth: subjective falsity) or whether the assertion additionally needs to be actually false (henceforth: objective falsity). Most philosophical definitions of lying require only subjective falsity, as expressed in the following, widely held view:

A lies to B if and only if there is a proposition p such that:

(L1) A asserts p to B, and.

(L2) A believes that p is false.Footnote 2

But some authors require a further condition:Footnote 3

(L3) p is false.

Let us call the view requiring only subjective falsity the subjective view of lying, and the view that additionally requires objective falsity (expressed by (L3)) the objective view of lying.

Which view is favoured by the ordinary concept of lying? The paper at hand starts with specifying the research question and then approaches this question by reviewing the relevant empirical findings. The findings are mixed and seemingly depend on which question-and-response format is employed. Three experiments were conducted to address this issue. The upshot is that the empirical findings favour the subjective view of lying, while those findings that seem to support the objective view are based on a misinterpretation of participants’ responses.

1.1 An already settled debate?

When reading recent papers on the folk concept of lying, one might encounter passages that give the impression that the debate has already been resolved in favour of the objective view. For instance, Chernak et al. (2021, p. 190) write:

In the same vein, Turri (2021, p. 2107) writes:

Aside from appealing to tainted responses to particular cases, subjective theorists have claimed that “the vast majority” reject objective accounts and that it “seem[s] peculiar that whether or not one is lying depends on luck,” such as one’s statement actually turning out false (Mahon, 2008, pp. 217–218). The empirical generalization about what a vast majority thinks is unsubstantiated and anecdotal reports of peculiarity don’t differ significantly from appealing to intuition. I am aware of no other evidence offered for subjective accounts.

Since these two papers neither describe nor cite papers that argue, on an empirical basis, for the subjective view of lying, one might wonder whether there is any empirical evidence in its favour. The review of the empirical literature below aims to correct this misleading impression.

1.2 Specifying the research question

The attentive reader has probably noticed that the title of this paper asks whether lying requires falsity, while the quote above (Chernak et al., 2021; see also Turri, 2021; Turri and Turri, 2021) claims that falsity is essential to lying. To avoid ambiguities and misunderstandings, let us first specify the question that the current paper is addressing.

There are cases with a certain structure for which the subjective and objective views of lying provide different verdicts. In these cases, the speaker says something she believes to be false in order to deceive the hearer. However, unbeknownst to the speaker, her statement is actually true. For illustration:

Library:

Pia and Ben are students at a university. Pia asks Ben where in the library she can find a certain book that she needs to prepare for an examination. Ben had a look at the book yesterday and remembers that it was located at “AB2c”. However, he tells Pia that the book is located at “LK9d” because he dislikes her and wants her to fail the examination. Unbeknownst to Ben, the library rearranged the books during the previous night and the book Pia is looking for is now actually located at “LK9d”.

In short, and at an abstract level:

S asserts p.

S believes p to be false.

p is in fact true.

For such subjectively false but objectively true statements, the subjective and objective views of lying provide different verdicts. Whereas the subjective view considers cases of this kind to be instances of lying, the objective view does not classify them as lying, because p is objectively true.Footnote 4

The question this paper aims to address – whether the ordinary concept of lying requires falsity – can now be operationalized as follows. Do most people consider subjectively false but objectively true statements to be lies? In statistical terms, do (significantly) more than 50% of participants classify subjectively false but objectively true statements as instances of lying? If the answer is “yes”, it seems reasonable to claim that the ordinary concept of lying does not require falsity.

It might be worth noting that even if the majority do classify such cases as lying, it can still be true that the prototypical lie – in the sense of: the features people usually have in mind when they think or are asked about the concept of lying – includes objective falsity. Accordingly, if the claim that “objective falsity is essential to lying” (Chernak et al., 2021; Turri and Turri, 2021) is to be understood in this rather weak sense, then the potential finding that people consider such cases to be lies would be compatible with this claim.Footnote 5 Moreover, such a finding would leave open the possibility that the ordinary concept of lying is inherently vague and to some degree context-dependent.

2 Literature review

The following review will be limited to experiments testing English-speaking adults since the literature for other languages is still quite sparse. Coleman and Kay (1981) were the first researchers to empirically test a subjectively false but objectively true case, which goes as follows:

One morning Katerina has an arithmetic test she hasn’t studied for, and so she doesn’t want to go to school. She says to her mother, “I’m sick.” Her mother takes her temperature, and it turns out to Katerina’s surprise that she really is sick, later that day developing the measles.

Question: Did Katerina lie?

The mean rating for this case was 5.16 on a 7-point scale (1: Non-Lie; 7: Lie). When we transform these ratings into a binary measure, 74% (50 out of 68) considered the speaker to be lying, while only 21% (14/68) indicated that Katerina did not lie (4 participants chose the neutral option “can’t say”).

Strichartz and Burton (1990) tested children of different ages, as well as 30 adults. The cases were presented in the form of puppet plays. An example of a subjectively false but objectively true case is the following:

(Spot runs away. Enter Chris.)

Chris: I wonder where Spot is? I bet he’s in the doghouse.

Mom: (Enters) Chris, where is Spot?

Chris: (Aside) Oh no, I don’t want Mom to know.

(To Mom) Spot ran away. (Exit Mom) Uh huh, that’s what I wanted to say.

(Exit Chris, nodding head.)

Question: When Chris said, “Spot ran away”, was Chris telling a lie, the truth, or something else?

The exact percentages for this kind of case are not provided, but a result figure indicates that about 70% of the adults considered subjectively false but objectively true cases to be instances of lying, while less than 20% judged that the speaker told the truth. (The remaining participants chose the “something else” category.) Chernak et al. (2021, see the quotation above) as well as Turri and Turri (2021) cite this study as evidence for the objective view:

For example, in one study, a statement’s objective truth-value was the most important factor affecting lie attributions (Strichartz & Burton, 1990). We regret overlooking Strichartz and Burton’s important study in our earlier literature review. We now regard their paper (Strichartz & Burton, 1990) as the first study to explicitly consider and provide strong evidence for the hypothesis that objective truth-value is central to the ordinary lying concept (Turri & Turri, 2021, p. 758).

And indeed, Strichartz and Burton say at one point in their paper (p. 215):

Clearly the largest effect was the main effect of factuality for both lie and truth […].

However, it is rather explicitly stated that this effect was mainly driven by preschoolers and first graders, while adults based their judgements primarily on subjective falsity (p. 215):

Preschoolers and first graders clearly dichotomized their answers based solely on factuality. […] The responses of the fifth graders were transitional between those of the younger children and those of the adults on the weightings of the elements belief and factuality. When labelling a statement a lie, these children had begun to consider belief as well as factuality when deciding whether a statement was a lie. However, they were less willing than adults to let the belief system of the speaker override the factuality of the statement. […] The graph shows that for adults the belief system of the speaker overrode both the factuality of the statement and the intent to deceive.

A more recent study by Turri and Turri (2015, experiment 1) used the following scenario description

Grocery store

Jacob’s friend Mary recently posted information on the internet that will alert the public to serious corruption in the government. Soon some federal agents visit Jacob and ask where Mary is. Jacob realizes that they want to detain her for what she did. Jacob thinks that Mary is at her brother’s house. He is very concerned about Mary and does not want her to be detained. Jacob tells the agents, “She is at the grocery store on the corner.” However, unbeknownst to Jacob, Mary is at the grocery store, where the agents find and arrest her.

Did Jacob lie about Mary’s location?/Did Jacob tell the truth about Jacob’s location? [Yes/No]

In line with the previously reported findings, the clear majority of participants (~ 80%) answered the lie-question with “yes” (and the truth-question with “no”).

These two studies (Coleman and Kay, 1981; Strichartz and Burton, 1990) and the first experiment by Turri and Turri (2015) seem to paint quite a clear picture. The majority of participants consider speakers who make a believed-false but actually true statement to be lying. Hence, the ordinary concept of lying does not seem to require objective falsity, and instead favours the subjective view of lying.Footnote 6

2.1 The first challenge to the subjective view: Turri and Turri (2015)

The reported findings strongly suggest that empirical support for the subjective view stands on firm ground. However, Turri and Turri (2015) found an ingenious way to challenge this claim by pointing to a potential flaw in all of these studies. It is worth going through their paper in a bit more detail.

As mentioned above, Turri and Turri (2015) found in their first experiment that about 80% of participants chose the option stating that Jacob lied. However, Turri and Turri provided two explanations for why this finding might not provide evidence for the subjective view. First, participants might have answered the question from the perspective of the speaker, who was not aware that his statement was actually true. Second, participants might have answered “yes” to the question of whether Jacob lied just to express their disapproval of the speaker’s attempt to deceive the federal agents. To address these concerns, they ran a second and third experiment in which the format of the test question and the response option was changed accordingly. (I refer to this design of the response options as Contrast.) The scenario was a shortened version of the one that was previously employed:

Grocery Store (shortened)

Jacob’s friend Mary recently posted information on the internet that will alert the public to serious government corruption. Soon some federal agents visit Jacob and ask where Mary is, in order to detain her. Jacob thinks that Mary is at her brother’s house, so he tells the agents, “She is at the grocery store”. In fact, Mary is at the grocery store.

Which option best describes Jacob?

Experiment 2:

He tried to tell a lie and succeeded in telling the truth.

He tried to tell a lie but failed to tell a lie.

Experiment 3:

He tried to lie and actually did lie.

He tried to lie but only thinks he lied.

In Experiment 2, the clear majority of participants chose “He tried to tell a lie but failed to tell a lie”, and 90% in Experiment 3 chose “He tried to lie but only thinks he lied”. Turri and Turri (2015) interpreted these findings as evidence for the claim that lying requires objective falsity.

However, Wiegmann et al. (2016) subsequently defended the subjective view by pointing to a potential flaw of the Contrast design (Turri & Turri, 2015). They argued that splitting up the response options in the way Turri and Turri did is unnatural from the perspective of the subjective view. According to the subjective view, trying to lie virtually always means that one did indeed lie, because the objective truth status of the utterance is irrelevant. In order to lie, the speaker only needs to assert something she believes to be false – and it seems difficult to imagine that a speaker tried to lie but did not end up lying. Following this line of reasoning, Wiegmann and colleagues (2016) speculated that participants might have reinterpreted the experimental task as not (only) being about lying, but as concerning objective falsity, i.e. whether the speaker succeeded/failed in saying something false (which is a salient feature of the vignette). To test this hypothesis, Experiment 2 and Experiment 3 by Turri and Turri (2015) were replicated and extended with additional conditions that aimed to make clear that the task is not about whether Jacob said something true or false. In order to block this unwarranted interpretation, while keeping the format close to Turri and Turri’s (2015), only the fact that what Jacob said turned out to be true was added to the response options:

Experiment 2 extended:

He tried to tell a lie and succeeded in telling a lie although what he said turned out to be true.

He tried to tell a lie but failed to tell a lie because what he said turned out to be true.

Experiment 3 extended:

He tried to lie and actually did lie although what he said turned out to be true.

He tried to lie but only thinks he lied because what he said turned out to be true.

In both experiments, the results were similar to those usually obtained with a simple question (e.g. “Did the speaker lie?”) and simple response options (e.g. Yes/No): 72% in the extended version of Experiment 2 and 81% in the extended version of Experiment 3 chose the option stating that the agent lied. Moreover, the authors showed that employing a question format with a trying-and-succeeding/failing part leads to very odd results in cases that are uncontroversial (see below for details), adding further evidence that the Contrast design used by Turri and Turri (2015) does not produce valid lie judgements.

To sum up, the studies by Wiegmann and colleagues (2016) seemed to have re-established the claim that empirical evidence supports the subjective view of lying, which does not require falsity.

2.2 The second challenge to the subjective view: Turri and Turri (2021)

Recently, Turri and Turri (2021) presented an experiment (Experiment 3) to challenge the subjective view of lying again.Footnote 7 They reiterated their claim that perspective taking has inflated lie attributions in studies that used a simple question-and-response format. Notice that Wiegmann and colleagues (2016) did not demonstrate that perspective taking is not a problem. While they provided strong evidence that there are serious problems with the experimental setup employed by Turri and Turri (2015), they did not show that perspective taking was not a problem in employing a simple question-and-response format.

At this point, it is worth spelling out how perspective taking could be a problem. First, participants might think that their task is to judge how things seem from the perspective of the agent; and since the agent is not aware of the fact that her assertion is actually true, they might believe that they are not allowed to take this fact into account. Second, it would also be a problem if participants “completely” think in the shoes of the agent, thereby becoming unaware of the fact that the statement is actually true. In both cases, lie attributions could be artificially inflated because participants might have judged that the agent did not lie if they had taken into account that her statement was factually true.Footnote 8

To prevent perspective taking, Turri and Turri (2021) employed a question-and-response format intended to “respect the appearance/reality distinction and disentangle the agent’s perspective from what actually occurs” (p. 10). In their experiment (Turri & Turri, 2021, Experiment 3) used the following vignette and question format:

Pool

Karen’s neighbor Anthony just got back from vacation. Anthony asks Karen, “Did your children swim in my pool while I was gone?” Karen thinks that her children did swim in his pool, so she says, “No, they did not swim in your pool.” In fact, they did not swim in the pool.

Which option better describes the case?

Karen thinks she lied and did actually lie.

Karen thinks she lied but did not actually lie.

When Turri and Turri (2021) used this version of a Contrast design, the clear majority of participants (74%) chose the option “Karen thinks she lied but did not actually lie”. The authors interpreted this finding as evidence for two claims. First, lie attributions in experiments using a simple question format (e.g. “Did Karen lie to her neighbour? [Yes/No]”) were inflated due to perspective taking. Second, if measures are applied to inhibit perspective taking, the vast majority of participants judge that a speaker making a believed-false but true statement does not lie (at least in the case above).

Are these conclusions warranted? One might worry that the question-and-response format they employed is quite similar to the Contrast design used in their earlier paper, which has been shown to be problematic (Wiegmann et al., 2016; see above). In the following, it is argued that the new version of the Contrast design (Turri & Turri, 2021) does indeed exhibit some of the very same problematic features as the old one.

For the following discussion, let us keep in mind that a salient feature of the Pool case is that Karen’s statement is subjectively false but objectively true, i.e. the speaker tries to say something false but ends up saying something true. Furthermore, let us refer to the first part of Turri and Turri’s (2021) response options (“Karen thinks she lied”) as the “think-part”, and to the other part as the “actually-part” (“but did not actually lie”/ “and did actually lie”). Notice that splitting up the response options into a think- and an actually-part is again, in some sense, unnatural from the perspective of the subjective view of lying – one might even say that it presupposes the objective view. According to the subjective view, believing oneself to have lied and actually having lied cannot come apart in cases like Pool. As Marsili (2016) puts it, “If you think you lied, you lied”, because it does not matter for the subjective view whether your statement is actually true (or false). In this sense, the wording of the response options might appear unnatural for participants who have a subjective view of lying, and could thus have caused some confusion as to, first, what the experimental task is about or, second, how to interpret the response options.

The first worry (what the experimental task is about) might be fuelled by the fact that the test question (“Which option better describes the case?”) does not make it explicit that the task is about judging whether Karen lied (in contrast to a simple question like “Did the speaker lie?”). To spell out this worry, perhaps some participants thought that their task was to indicate the “structure” of the scenario, i.e. that Karen wanted to deceive her neighbour by saying something she believed to be false, but failed to do so because her assertion was actually true. If this worry, which is similar to the criticism of experiment 2 & 3 in Turri and Turri (2015) above, is on the right track, then participants who chose “Karen thinks she lied but did not actually lie” perhaps did not want to indicate that Karen did not lie, but only that she tried to deceive her neighbour but failed to do so because what she said was actually true. In that case, the finding that the vast majority chose this option would not tell us whether the majority favour the objective view of lying (or the subjective view).

The second – to some degree similar – worry (how participants interpreted the response options) could be motivated as follows. According to the subjective view, it is difficult to imagine how a person could be mistaken about whether she lied in cases like Pool. The speaker has all the information she needs in order to know whether or not she lied, because objective truth is irrelevant for lying (“If you think you lied, you lied”). Hence, participants who have a subjective concept of lying might have interpreted the “thinks she lied”-part of the response option as referring to the question of whether Karen lied, while taking the “did not actually lie”-part to correspond to the salient fact that her assertion was not actually false. In other words, some participants who chose “Karen thinks she lied but did not actually lie” might have wanted to indicate that that, first, Karen did lie and, second, that her statement was actually true. If this was the case, then choosing the option “Karen thinks she lied but did not actually lie” would again not provide evidence for the objective view.

These worries become more plausible if we look at a previous finding by Wiegmann and colleagues (2016). In Experiment 4, participants were presented with a short vignette in which a person (Jacob) makes and tries to keep a promise, but eventually fails to keep it. The task was to choose the option that better describes the case and the two response options offered were structurally similar to the ones employed by Turri and Turri (2015), namely “He tried to make a promise but failed to make a promise” and “He tried to make promise and succeeded in making a promise”. Strikingly, the majority chose the option stating that Jacob tried but failed to make a promise, although it is crystal clear that he did make a promise. Since the participants denied the obvious, this suggests that there is something wrong with the Contrast design. Presumably, what happened is close to the worries outlined in the preceding paragraphs. However, only empirical experiments can tell us whether the concerns raised above actually do apply to Turri and Turri’s (2021) recent experiment with the Pool case, which brings us to the three experiments of the current paper.

3 Experiment 1

As described above, Turri and Turri (2021) argue that perspective taking artificially inflates lie attributions in studies that employ a simple question-and-response format. This claim seems to be based on the following reasoning. If perspective taking causes artificially inflated lie attributions, then employing a question-and-response format that inhibits perspective taking should result in a lower rate of lie attributions. Response options of the form “S thinks she lied but did not actually lie”/“S thinks she lied and actually did lie” do “respect the appearance/reality distinction and disentangle the agent’s perspective from what actually occurs” (p. 10), thereby inhibiting perspective taking. When these response options are actually employed, it turns out that significantly more participants choose the “S thinks she lied but did not actually lie”-option than choose the “S did not lie”-option. So perspective taking has artificially inflated lie attributions in previous studies that employed a simple question-and-response format.

For this reasoning to be valid, two assumptions need to be made. First, the measures implemented to inhibit perspective taking do not affect lie attributions in any way other than what was intended (in more psychological terms: no confound was present). Second, participants choosing the option “S thinks she lied but did not actually lie” express the same judgement as when choosing “S did not lie”, namely that the speaker did not lie. These assumptions, however, could be avoided if we were to find a way to inhibit perspective taking without changing the wording of the response options; and there seems to be a straightforward way to do this. For instance, one could just tell the participants explicitly that they should answer the question of whether a speaker is lying from their (i.e. each participant’s) perspective, and explicitly state that they are allowed to take into account all the information provided in the vignette. This method was employed in the experiment described next.

3.1 Participants

Participants were recruited using Prolific Academic, completed an online survey implemented in Unipark, and were required to be at least 18 years old and native English speakers. The experiment was run until the valid responses of 300 participants were collected (150 in each condition). Mean age was 33 years, 44% were male and 56% female. Participants received £0.25 for an estimated 2 min of their time (£7.50/h).

3.2 Design, procedure and materials

Participants were randomly assigned to one of two conditions (Prompt vs. No Prompt). All participants were then presented with Pool scenario (Turri & Turri, 2021):

Only in the Prompt condition, participants saw the following prompt (in bold font) before the test question:

Please answer the following question from your perspective, which means that you are allowed to take into account all of the facts provided in the description of the story.

The wording of the lie-question was as follows:

Did Karen lie to her neighbor?

Yes.

No.

Afterwards, two questions were asked to make sure that the participants understood the scenario in the intended way. The first asked whether Karen intended to deceive her neighbor; the second whether Karen’s children actually swam in the neighbor’s pool. Only the data of participants who answered both questions correctly were used in the following analysis (the same applies to the other experiments).

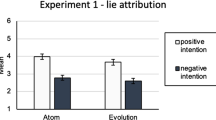

3.3 Results

The results are summarized in Fig. 1. In both conditions, the clear majority of participants (110 out of 150, i.e. 73.3%, in Prompt; and 109 out of 150, i.e. 72.7%, in No Prompt) judged that Karen did lie to her neighbour (binomial test against 0.5, p < .0001).Footnote 9 The difference between the two conditions was not significant, χ21, N = 300 = .0169, p = .897.

3.4 Discussion

Experiment 1 manipulated perspective taking while employing a simple question-and-response format. In just one of the two conditions, participants were explicitly told that they should judge the scenario from their own perspective and that they were allowed to take into account all the information provided by the scenario. It was found that this manipulation had no effect, suggesting that perspective taking might not be the reason why lie attributions in previous studies that used a simple question-and-response format were higher than in Turri and Turri’s (2021) study. Instead, these results raise the question of whether there is a problem with the question-and-response format employed by Turri and Turri.

4 Experiment 2

The previous experiment adds to the previously motivated worry that participants who chose “Karen thinks she lied but did not actually lie” might not have wanted to indicate that Karen did not lie. To test this possibility, participants in the current experiment were first presented with the Karen case and the Contrast format (“Which option better describes the case? Karen thinks she lied and did actually lie/Karen thinks she lied but did not actually lie”) used by Turri and Turri (2021). Then, after choosing one of the two response options, they were asked how their choice should be classified in terms of the question of whether Karen lied, either as “Karen did lie” or as “Karen did not lie”. This classification task came in two variants. In one condition, participants were asked how they themselves would classify the option they chose, while participants in the other condition were asked to guess how a researcher interested in the question of whether Karen lied would classify the response they (the participant) provided.Footnote 10 Assuming that some of the participants who chose the “Karen thinks she lied but did not actually lie”-option indeed did not mean to express that Karen did not lie, the following – and perhaps absurd-sounding – prediction follows. The number of participants who first choose “Karen thinks she lied but did not actually lie” will be significantly and substantially higher than the number of participants who classify this response as “Karen did not lie” in the subsequent classification task.

4.1 Participants

Participants were again recruited using Prolific Academic, completed an online survey implemented in Unipark, and were required to be at least 18 years old and native English speakers. The experiment was run until the valid responses of 600 participants were collected (~ 150 in each of the four conditions). Mean age was 35 years, 39% were male, 60% female, and 1% non-binary. Participants received £0.25 for an estimated 2 min of their time (£7.50/h).

4.2 Design, procedure and materials

Participants were randomly assigned to one of four conditions in a 2 (Lie question: Simple vs. Turri) * 2 (classification: Researcher vs. Self) between-subjects design. All participants were then presented with the Pool vignette used by Turri and Turri (2021):

In the Simple condition, the wording of the lie-question was as follows:

Did Karen lie to her neighbor?

Yes.

No.

In the Turri condition, the wording of the test question was identical to the version Turri and Turri used to inhibit perspective taking:

Which option better describes the case?

Karen thinks she lied and did actually lie.

Karen thinks she lied but did not actually lie.

On the next page, the scenario was presented again and participants were asked a question about the classification of their response.

In the Researcher condition, the classification question was:

Imagine a researcher is interested in whether people think that Karen lied.

How will this researcher classify the option you chose on the previous page?

The researcher will classify my response as “Karen did lie”.

The researcher will classify my response as “Karen did not lie”.

In the Self condition, the question was worded as follows:

Just to make sure we understood you correctly and classify your answer accordingly:

How do you classify your previous judgment in terms of the question of whether Karen lied?

Karen did lie.

Karen did not lie.

4.3 Results

The results are summarized in Figs. 2 and 3. Let us first look at the Simple condition (Fig. 1). When asked whether Karen lied to her neighbour, a clear majority of participants indicated that she did so (72% in the Researcher condition and 66% in the Self condition, p < .001). The results for the subsequently asked classification question look very similar to the results for the lie question. In the Researcher condition, 73% indicated that a researcher would classify their response as “Karen did lie” (vs. 72% previously responding “yes” to the question “Did Karen lie?”); in the Self condition, 71% indicated that they would classify their response as “Karen did lie” (vs. 66% previously responding “yes” to the question “Did Karen lie?”).

Let us define consistency across the lie question and the classification question as (a participant) responding “yes” to the lie-question and choosing the response including “Karen did lie” to the subsequent classification question, or responding “no” to the lie question and “Karen did not lie” to the classification question. Applying this measure revealed that 94% of all participants in Researcher provided consistent answers, and that 93% did so in the Self condition.

Figure 3 summarizes the results for the condition in which the Contrast design from Turri and Turri (2021) was used. When asked “Which option better describes the case”, a very clear majority of participants chose “Karen thinks she lied but did not actually lie” (87% in the Researcher condition, p > .001 and 82% in the Self condition, p < .001). The results for the subsequently asked classification question are as follows. In the Researcher condition, only a minority of 38% (p = .0025) indicated that a researcher would classify their response as “Karen did not lie” (vs. 87% previously having chosen “Karen thinks she lied but did not actually lie”). In the Self condition, only a minority of 36% (p < .001) indicated that they would classify their response as “Karen did not lie”, although 82% chose the option stating that Karen did not actually lie on the previous page. If we define consistency across these two questions as above, i.e. choosing “Karen thinks she lied and did actually lie” when responding to the lie-question and “Karen did lie” when subsequently asked to classify their previous choice, or responding “Karen thinks she lied but did not actually lie” to the lie question and “Karen did not lie” to the classification question, then only 48% of all participants in Researcher provided consistent answers, and only 52% did so in the Self condition.

Results of Experiment 1 for the condition in which Turri and Turri’s (2021) Contrast format was used (“Which option better describes the case? [Karen thinks she lied and did actually lie/Karen thinks she lied but did not actually lie]”). Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals

The proportions of participants providing consistent responses when Turri and Turri’s Contrast format was employed were significantly lower than in the corresponding conditions in which the simple question- and answer-format was used (48% vs. 94% in the Researcher condition, χ21, N = 300 = 62.77, p < .001; and 52% vs. 93% in the Self condition; χ21, N = 300 = 74.97, p < .001).

Finally, let us limit our analysis to the Contrast conditions and to those participants who first chose the option that Turri and Turri (2021) counted as favouring the objective view. Out of 266 participants who first chose the option “Karen thinks she lied but did not actually lie”, the majority (154, i.e. 58%, p = .012) chose “Karen did lie” in the subsequent classification task.

4.4 Discussion

Turri and Turri (2021) found that when participants are provided with two response options of the form “S thinks she lied but did not actually lie” and “S thinks she lied and did actually lie”, the clear majority choose the former option. The authors took this finding as evidence that the clear majority did not attribute a lie to Karen, and that lie attributions in studies using a simple question-and-answer format like “Did S lie? [Yes/No]” are inflated due to perspective taking. The findings of the current experiment call these claims into question. Although the clear majority chose the option “Karen thinks she lied but did not actually lie” when asked which option better describes the case, most participants responded that Karen lied when asked how they would classify their previous response. The same pattern occurred when participants were asked to indicate how a researcher interested in the question of whether Karen lied would classify their response. This finding might appear surprising at first sight, but it is consistent with the findings of Wiegmann and colleagues (2016).Footnote 11

5 Experiment 3

The aim of the concluding experiment is to make sure that participants take into account the fact that the speaker’s statement was true, and to explicitly test whether this fact means (entails) that the person in the scenario did not lie. Participants were asked which option better described the Karen case, and were given two response options. One stated that the speaker lied although what she said was actually true, while the other stated that she did not lie because what she said was actually true. This format prevents participants from neglecting the objective truth value and allows the subjective view to be explicitly tested against the objective view.

5.1 Participants

Participants were recruited using Prolific Academic, completed an online survey implemented in Unipark, and were required to be at least 18 years old and native English speakers. The experiment was run until the valid responses of 150 participants were collected. Mean age was 25 years, 27% were male,71% female, and 2% non-binary. Participants received £0.15 for an estimated 1 min of their time (£9/h).

5.2 Design, procedure and materials

All participants were again presented with the Pool vignette used by Turri and Turri (2021):

The wording of the test-question was as follows:

Which option better describes the case?

Karen lied to her neighbour although what she said was factually true.

Karen did not lie to her neighbour because what she said was factually true.

5.3 Results

123 out of 150 (82%) participants chose the option stating that Karen lied to her neighbour, despite the fact that what she said was actually true (p < .001).

5.4 Discussion

Using response options that explicitly stated the objective truth of the protagonist’s statement and asked whether this fact does or does not prevent the speaker from lying, the clear majority indicated that the speaker lied although what she said was actually true, thereby providing evidence for the subjective view.

6 General discussion

Does the ordinary concept of lying require objective falsity? This paper started addressing this question by evaluating empirical studies including scenarios that allow the objective view of lying to be tested against the subjective view, namely scenarios where the following is true of a speaker S:

S asserts p.

S believes p to be false.

p is in fact true.

In such cases, the subjective view holds that the speaker is lying because she asserts something she believes to be false, whereas the objective view denies this claim by pointing to the fact that the assertion was true. Studies employing a simple question-and-response format such as “Did the speaker lie? [Yes/No]” favoured the subjective view of lying by consistently finding that about 70% of participants considered subjectively false but objectively true assertions to be cases of lying. These findings, however, were challenged by two papers by Turri and Turri (2015, 2021). The first challenge (Turri & Turri, 2015) was successfully answered by Wiegmann and colleagues (2016), who pointed to a flaw in the experimental design employed by Turri and Turri (2015).

The second challenge (Turri & Turri, 2021) has been addressed in this paper. Turri and Turri claimed that lie attributions in studies employing a simple format are inflated due to perspective taking. To prevent perspective taking, the authors employed the following question-and-response format (Contrast):

Which option better describes the case?

Speaker thinks she lied and did actually lie.

Speaker thinks she lied but did not actually lie.

When this format was used, the clear majority of participants chose the option stating that the speaker did not actually lie. Turri and Turri (2021) interpreted this finding as evidence for the claim that the majority do not consider a speaker making a believed-false but actually true statement to be lying, and that perspective taking had inflated lie attributions in previous studies that used a simple question-and-answer format.

The three experiments reported in this paper question this interpretation by providing evidence that a substantial proportion of participants in their study did not interpret the response options as Turri and Turri (2021) assumed. In particular, these new findings indicate that many participants who chose “Speaker thinks she lied but did not actually lie” did not want to indicate that the speaker did not lie.

In Experiment 1, perspective taking was manipulated while using a simple question-and-response format. Participants in one condition were told to approach the question of whether Karen lied from their perspective, and that they were allowed to take into account all the information provided in the scenario description (this information was missing in the other condition). It was found that the majority of participants in both conditions judged that the speaker lied, which is in line with how the subjective view of lying would evaluate this case. Moreover, it was found that the experimental manipulation had no effect, suggesting that perspective taking is not the reason why lie attributions in previous studies that used a simple question-and-response format were higher than in Turri and Turri’s (2021) study. Instead, the results hinted at potential problems with Turri and Turri’s design and added to the previously motivated worry that participants choosing “Speaker thinks she lied but did not actually lie” do not necessarily mean to indicate that the speaker did not lie.

Experiment 2 followed up on this worry. Participants were first presented with the scenario Contrast design used by Turri and Turri (2021). Then, after choosing one of the two response options, they were asked how their choice should be classified in terms of the question of whether Karen lied: either as “Karen did lie” or as “Karen did not lie”. This classification task came in two variants. In one condition, participants were asked how they themselves would classify the option they chose, while participants in the other condition were asked to guess how a researcher interested in the question of whether Karen lied would classify their response. Although the clear majority chose the option “Karen thinks she lied but did not actually lie” when asked which option better describes the case, most participants responded that Karen lied when asked how they would classify their previous response. The same pattern occurred when participants were asked to indicate how a researcher interested in the question of whether Karen lied would classify their response. These findings strongly suggest that participants interpreted the response options differently from how Turri and Turri meant them to be understood.

In the concluding Experiment 3, the response options were worded in a way that allowed for a rather explicit test of the subjective view against the objective view. One option stated that the speaker lied although what she said was actually true, while the other stated that she did not lie because what she said was actually true. The clear majority indicated that the speaker lied although what she said was actually true, thereby providing evidence for the subjective view.

To sum up the empirical part, the experiments reported in this paper provide strong evidence that most participants consider subjectively false but objectively true statements to be lies. Moreover, they also explain why some studies seemingly found evidence for the objective view. On the basis of these findings and the review of the literature it is concluded that empirical evidence consistently favours the subjective view of lying, according to which lying does not require objective falsity.

Given the widely held view that consistency with ordinary language is a desideratum of a philosophical definition of lying, this paper concludes that such a definition should do without a condition that requires objective falsity. In line with the predominant view in the philosophical literature, the empirical evidence strongly suggests instead that what a speaker says needs to be believed-false, but need not actually be false.

Notes

Of course, there might be interesting and important philosophical projects for which capturing the folk concept of lying is not (crucially) important. Moreover, the folk concept of lying might eventually turn out to be flawed (e.g. by being inconsistent), in which case it will probably become less interesting and less important for the philosophical project of defining lying. However, in the absence of such evidence, and given the aim of developing a definition of lying that is closely tied to the folk concept of lying, empirical studies suggest themselves.

One might think that such cases are of little relevance because their probability of occurring is quite low (but see Stokke, 2018, p. 33–34, for plausible candidate cases). However, it does not seem to be a coincidence that these cases feature rather prominently in the theoretical and empirical literature (see Mahon, 2016, for a theoretical overview; see Wiegmann and Meibauer, 2019, for an empirical overview). Indeed, they are critical for assessing whether lying requires objective falsity, which is at the heart of how we conceive of lying. If only subjective falsity is required, then lying is essentially located within a person. As its heart, there is the mismatch between what a person believes and what she says, which puts lying fully under the person’s control – in order to lie, she only needs to say something she believes to be false. By contrast, if objective falsity is additionally required, then external factors become important in the form of a further necessary mismatch, between what a person says and how things are in the world. Accordingly, lying would not be fully under a person’s control, because she could fail to lie when trying to, namely when she makes a believed-false statement that turns out to be true.

Turri and Turri (2021) commit themselves to this weaker claim but also discuss – without rejecting – the stronger claim that lying requires falsity.

Additionally, Icard (2019) reports the results of a pilot study that also support the subjective view of lying.

My focus is on this experiment because it is the only one in the paper (Turri & Turri, 2021) that challenges the claim that most participants in subjectively false but objectively true cases judge that the speaker lied.

Of course, it would not be a problematic form of perspective taking if participants intentionally judged the case from the perspective of the agent because they think that this is the relevant perspective for judging whether she lied.

Unless otherwise indicated, p-values in the remainder of the test also refer to a binomial test against chance-level, i.e. 50%, two-tailed.

Two variants were used to see whether they converge, which would speak in favour of the robustness of the results.

It’s beyond the scope of this paper to offer a psychological mechanism of what exactly caused these prima facie puzzling results, but I will make a guess. For reasons indicated in the introduction, participants might have interpreted the response option “Karen thinks she lied but did not actually” as “Karen thought what she said was false but it actually turned out to be true”, which fits with the salient feature of the case that Karen said something she believed to be false but which turned out to be true.

References

Carson, T. L. (2006). The definition of lying. Nous, 40(2), 284–306.

Carson, T. L. (2010). Lying and deception: Theory and practice. Oxford University Press.

Chernak, E., Dietrich, K., Raspopovic, A., Turri, S., & Turri, J. (2021). Lying by omission: Experimental studies. Filozofia Nauki, 29(2), 189–208.

Coleman, L., & Kay, P. (1981). Prototype semantics: The English word lie. Language, 57(1), 26–44.

Fallis, D. (2009). What is lying? Journal of Philosophy, 106(1), 29–56.

García-Carpintero, M. (2018). Sneaky assertions. Philosophical Perspectives, 32(1), 188–218.

Harris, D. W. (2020). Intentionalism and bald-faced lies. Inquiry : A Journal Of Medical Care Organization, Provision And Financing, 1–18.

Icard, B. (2019). Lying, deception and strategic omission: definition and evaluation (Doctoral dissertation, Paris Sciences et Lettres (ComUE)).

Mahon, J. E. (2008). Two definitions of lying. International Journal of Applied Philosophy, 22(2), 211–230

Mahon, J. E. (2016). The definition of lying and deception. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2016 ed.). Retrieved from https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/lying-definition/

Maitra, I. (2018). Lying, acting, and asserting. In E. Michaelson, & A. Stokke (Eds.), Lying: Language, Knowledge, Ethics, and politics (pp. 65–82). Oxford University Press.

Marsili, N. (2016). Lying by promising: A study on insincere illocutionary acts. International Review of Pragmatics, 8(2), 271–313.

Pepp, J. (2019). The aesthetic significance of the lying-misleading distinction. The British Journal of Aesthetics, 59(3), 289–304.

Saul, J. M. (2012). Lying, misleading, and what is said: An exploration in philosophy of language and in ethics. Oxford University Press.

Stokke, A. (2016). Lying and misleading in discourse. Philosophical Review, 125(1), 83–134.

Stokke, A. (2018). Lying and insincerity. Oxford University Press.

Strichartz, A. F., & Burton, R. V. (1990). Lies and truth: A study of the development of the concept. Child Development, 61(1), 211–220.

Turri, J. (2021). Objective falsity is essential to lying: An argument from convergent evidence. Philosophical Studies, 178(6), 2101–2109.

Turri, A., & Turri, J. (2015). The truth about lying. Cognition, 138, 161–168.

Turri, A., & Turri, J. (2021). Lying, fast and slow. Synthese, 198(1), 757–775.

Viebahn, E. (2020). Lying with presuppositions. Noûs, 54(3), 731–751.

Viebahn, E. (2021). The lying-misleading distinction: A commitment-based approach. The Journal of Philosophy, 118(6), 289–319.

Wiegmann, A., & Meibauer, J. (2019). The folk concept of lying. Philosophy Compass, e12620.

Wiegmann, A., Samland, J., & Waldmann, M. R. (2016). Lying despite telling the truth. Cognition, 150, 37–42.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by an Emmy Noether grant of the German Research Foundation (DFG) [grant number 391304769].

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

I declare that I have no potential conflict of interest (financial or non-financial).

Informed consent

Participants gave their informed consent in all experiments (and all ethical standards were met).

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wiegmann, A. Does lying require objective falsity?. Synthese 202, 52 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-023-04291-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-023-04291-3