Abstract

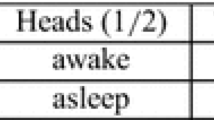

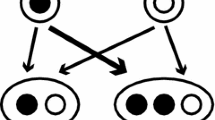

Concerning the notorious Sleeping Beauty problem, philosophers have debated whether 1/2 or 1/3 is rational as Beauty’s credence in (H) the coin’s landing heads. According to Kierland and Monton, the answer depends on whether her goal is to minimize average or total inaccuracy because, while the expected average inaccuracy of Halfing (i.e., assigning 1/2 to H) is smaller than that of Thirding (i.e., assigning 1/3 to H), the expected total inaccuracy of Thirding is lower than that of Halfing. In this paper, I argue that Halfing is average accuracy dominated but Thirding is not; and that each of the standard forms of Halfing and Thirding regards a different credence assignment as better than itself in terms of total accuracy. Therefore, Halfing is irrational, and Thirding is likely to be rational, for the goal of minimizing average inaccuracy; but both Halfing and Thirding, at least in their standard forms, are irrational for the goal of minimizing total inaccuracy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

See Titelbaum (2013) for a survey.

See Sect. 5 for the defintions of standard forms of Halfing and Thirding.

Lewis (1979) introduces another type of propositions, called “centered propositions,” whose truth values vary relative to individuals as well as times. Indeed, there is a variant of the Sleeping Beauty puzzle in which centered propositions play an important role. I discuss it in Kim (forthcoming, Sect. 7).

I feel grateful to an anonymous reviewer for advising me to add this section.

I assume that a physical system’s position and momentum can change with time. The disputed issue is only whether chances change.

Later, I will consider two variants of Brier score as inaccuracy measures.

In a footnote, K &M write “Here the reader can substitute her preferred account of chances which aren’t solely subjective, such as frequencies, propensities, or objective chances” (2005, p. 387, footnote 8).

Pettigrew (2016) uses “strongly (weakly) current chance \({\mathcal {I}}\)-dominates,” which is quite mouthful. For brevity, I omit “current chance” in this paper.

I impose this constraint on CD because the base functions, \(p^{1}\left( \cdot \right) ,\ldots ,p^{n}\left( \cdot \right) \), are not defined over proper tensed propositions.

See Joyce (2009) for a more detailed exposition and defense of avoiding extreme modesty as a necessary condition for credal rationality (p. 277).

Not a typo.

So, CCEID can now apply to probability functions whose domains include some proper tensed propositions. This is because the domain of base functions has been expanded to include such propositions.

See Pettigrew (2016, Chapter 10) for his original defense of CCEID.

Recall that \( H_{1}=H \& MON,\) \( T_{1}=T \& MON,\) and \( T_{2}=T \& TUE.\)

Which timeslice must a count as relevant at t in w? One answer is that every timeslice in w with \(c(\cdot )\) as her credence function is relevant. Another answer is that only a’s temporal parts in w with \(c(\cdot )\) (as ...) can be relevant. In this paper, I will remain neutral between these two answers. Also, an anonymous reviewer points out that, even if an agent cares about the accuracy of some non-present credence function, she can rationally select her present credence function by calculating the average inaccuracies of the candidates. For example, suppose that, waking up on an unknown day, Beauty equally cares about the accuracies of her credence functions on Monday and Tuesday mornings but she is a causal decision theorist. Then, Beauty will choose her credence function by calculating average inaccuracies; for, the accuracy of her non-present credence function is causally independent from the choice of her present credence function. This is an interesting issue but, due to limitation in length, I will not discuss it here.

Since the coin is tossed before t, either \(ch_{t}\left( WK\right) =1\) or \(ch_{t}\left( WK\right) =0\). In the latter case, \(ch_{t}\left( \cdot |WK\right) \) is undefined. However, when Beauty wakes up (unbeknownst to her) on Monday morning, she can ignore that case in calculating \(\text {Exp}_{\mathcal{A}\mathcal{I}}\left( c^{\left\langle x,y,z\right\rangle }|ch_{t}\left( \cdot |WK\right) \right) \) because she is then treating \(ch_{t}\left( \cdot \right) \) as a candidate for \(ch_{pres}\left( \cdot \right) \) and, at that moment, she knows that \(ch_{pres}\left( WK\right) =1\).

Proof: Without loss of generality, we only show that it is not the case that (i) \(\text {Exp}_{\mathcal{A}\mathcal{I}}\left( c^{\left\langle u,u,v\right\rangle }|ch_{m}\left( \cdot |WK\right) \right) >\text {Exp}_{\mathcal{A}\mathcal{I}}\left( c^{\left\langle u',u',v'\right\rangle }|ch_{m}\left( \cdot |WK\right) \right) \) and (ii) \(\text {Exp}_{\mathcal{A}\mathcal{I}}\left( c^{\left\langle u,u,v\right\rangle }|ch_{t}\left( \cdot |WK\right) \right) \ge \text {Exp}_{\mathcal{A}\mathcal{I}}\left( c^{\left\langle u',u',v'\right\rangle }|ch_{t}\left( \cdot |WK\right) \right) .\) For this, suppose (i) and derive the negation of (ii) from it. Since \(c^{\left\langle u,u,v\right\rangle }\left( \cdot \right) \) and \(c^{\left\langle u',u',v'\right\rangle }\left( \cdot \right) \) are probability functions, \(2u+v=1=2u'+v'\) and \(0\le u,v,u',v'\le 1\). Hence, \(c^{\left\langle u,u,v\right\rangle }\left( \cdot \right) =c^{\left\langle u,u,1-2u\right\rangle }\left( \cdot \right) \), \(c^{\left\langle u',u',v'\right\rangle }\left( \cdot \right) =c^{\left\langle u',u',1-2u'\right\rangle }\left( \cdot \right) ,\) and \(0\le u,u'\le \frac{1}{2}\). By (18), \(6u^{2}-6u+2>6u'^{2}-6u'+2,\) which entails that \(\left( 2u-1\right) ^{2}>\left( 2u'-1\right) ^{2}\). Thus, \(u<u'\). By (19), \(\text {Exp}_{\mathcal{A}\mathcal{I}}\left( c^{\left\langle u,u,v\right\rangle }|ch_{t}\left( \cdot |WK\right) \right) <\text {Exp}_{\mathcal{A}\mathcal{I}}\left( c^{\left\langle u',u',v'\right\rangle }|ch_{t}\left( \cdot |WK\right) \right) \) iff \(6u^{2}<6u'^{2}.\) Done.

Proof: Consider any \(c^{\left\langle \frac{1}{2},y,z\right\rangle }\). Suppose PA2–PA4 and show that either \(c^{\left\langle \frac{1}{2},y,z\right\rangle }\) assigns 0 to \(T_{2}\) or \(c^{\left\langle \frac{1}{2},y,z\right\rangle }\) is strongly \(\mathcal{A}\mathcal{I}\)-dominated by a probability function that is not weakly \(\mathcal{A}\mathcal{I}\)-dominated or extremely \(\mathcal{A}\mathcal{I}\)-modest. Since \(c^{\left\langle \frac{1}{2},y,z\right\rangle }\) is a probability function, \(y+z=\frac{1}{2}\). By PA2, \(c^{\left\langle \frac{1}{2},y,z\right\rangle }\) is strongly \(\mathcal{A}\mathcal{I}\)-dominated by some probability function \(c^{\left\langle u,u,v\right\rangle }\) unless \(y=\frac{1}{2}\) and \(z=0\). Thus, either \(c^{\left\langle \frac{1}{2},y,z\right\rangle }\) assigns 0 to \(T_{2}\) or \(c^{\left\langle \frac{1}{2},y,z\right\rangle }\) is strongly \(\mathcal{A}\mathcal{I}\)-dominated by some \(c^{\left\langle u,u,v\right\rangle }\), in which case, by PA3 and PA4, \(c^{\left\langle u,u,v\right\rangle }\left( \cdot \right) \) is neither weakly \(\mathcal{A}\mathcal{I}\)-dominated nor extremely \(\mathcal{A}\mathcal{I}\)-modest. Done.

Recall: \(\text {Exp}_{\mathcal{T}\mathcal{I}}\left( \phi |\psi \right) \) is the expected total inaccuracy of \(\phi \) based on \(\psi .\)

I am grateful to the reviewer for pressing me to discuss this variant of the puzzle. However, if you are only interested in the original, you can skip this section without much loss.

Due to the length limitation, I leave the detailed verification of this fact to the reader.

References

Caie, M. (2015). Credence in the image of chance. Philosophy of Science, 82(4), 626–648.

Elga, A. (2000). Self-locating belief and the sleeping Beauty problem. Analysis, 60(2), 143–147.

Frege, G. (1956). The thought: A logical inquiry. Mind, 65(259), 289–311.

Groisman, B. (2008). The end of sleeping beauty’s nightmare. The British Journal for the Philosophy of Science, 59, 409–416.

Hall, N. (2004). Two mistakes about credence and chance. Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 82(1), 93–111.

Jeffrey, R. (1986). Judgmental probability and objective chance. Erkenntnis, 24(1), 5–16.

Joyce, J. M. (1998). A nonpragmatic vindication of probabilism. Philosophy of Science, 65(4), 575–603.

Joyce, J. M. (2009). Accuracy and coherence: Prospects for an alethic epistemology of partial belief. In F. Huber & C. Schmidt-Petri (Eds.), Degrees of belief (pp. 263–297). Springer.

Kierland, B., & Monton, B. (2005). Minimizing inaccuracy for self-locating beliefs. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 70(2), 384–395.

Kim, N. (2008). Sleeping beauty and shifted Jeffrey conditionalization. Synthese, 168(72), 295–312.

Kim, N. (2022). Sleeping beauty and the evidential centered principle. Erkenntnis. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10670-022-00619-6.

Lewis, D. K. (1979). Attitudes de dicto and de se. Philosophical Review, 88(4), 513–543.

Lewis, D. K. (1980). A subjectivist’s guide to objective chance. In R. C. Jeffrey (Ed.), Studies in inductive logic and probability (Vol. II, pp. 263–293). University of California Press.

Lewis, D. K. (2001). Sleeping beauty: Reply to Elga. Analysis, 61(3), 171–176.

Lewis, P. J. (2010). Credence and self-location. Synthese, 175, 369–382.

Luna, L. (2018). Sleeping beauty: Exploring a neglected solution. The British Journal for the Philosophy of Science, 71(3), 1069–1092.

Myrvold, W. (2022). Philosophical issues in quantum theory. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), The Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy. Stanford University.

Osborne, M. J. (2009). A course in game theory. MIT Press.

Pettigrew, R. (2016). Accuracy and the laws of credence. Oxford University Press.

Titelbaum, M. G. (2013). Ten reasons to care about the sleeping beauty problem. Philosophy Compass, 8(11), 1003–1007.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Gyeongsang National University Fund for Professors on Sabbatical Leave, 2021. I feel grateful to Richard Pettigrew and Jinho Lee for mathematical assistance and to Misook Kim for helping with the editing of the final version of this essay. Thanks Julia Staffel for advice on which journal to select. Also, I am grateful to the anonymous reviewers for raising various interesting objections. Finally, I would like to thank my dissertation supervisor, Phillip Bricker, who will retire this year. Thanks him for being the best teacher whom I know.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, N. Sleeping beauty and the current chance evidential immodest dominance axiom. Synthese 200, 458 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-022-03926-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-022-03926-1