Abstract

In this paper, we investigate the effect described in the literature as the Group Knobe Effect, which is an asymmetry in ascription of intentionality of negative and positive side-effects of an action performed by a group agent. We successfully replicate two studies originally conducted by Michael and Szigeti (Philos Explor 22:44–61, 2019), who observed this effect and provide empirical evidence of the existence of two related effects—Group Epistemic and Doxastic Knobe Effects—which show analogous asymmetry with respect to knowledge and belief ascriptions. We explain how the existence of the Group Knobe Effect and its epistemic and doxastic counterparts affects the philosophical debate on collective agency and intentionality and supports the intuitiveness of realism about collective agency among laypeople. We also critically assess the reasoning presented by Michael and Szigeti (2019) in favor of the realist-collectivist interpretation of their results (as opposed to the realist-distributivist interpretation). We argue that a thorough analysis of both their data and our new findings shows a rather wide range of differing intuitions among laypeople regarding the status of groups as agents. These results show that while some laypeople may have realist-collectivist intuitions, the contrary realist-distrubutivist intuitions are also widespread and the claim that the majority of laypeople hold collectivist intuitions regarding group agency is unjustified.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In this paper, we investigate the effect described in the literature as the Group Knobe Effect (GKE), that is an asymmetry in ascription of intentionality of negative and positive side-effects of an action performed by a group agent. We replicate two studies of Michael and Szigeti (M&S) (2019), who were the first to observe this effect and provide empirical evidence of the existence of two other related effects—Group Epistemic and Doxastic Knobe Effects (GEKE and GDKE)—which show analogous asymmetry with respect to knowledge and belief ascriptions. We explain how the existence of the GKE and its epistemic and doxastic counterparts affects the philosophical debate on collective agency and intentionality and supports the intuitiveness of realism about collective agency among laypeople. We also critically assess the reasoning presented by Michael and Szigeti (2019) in favor of the realist-collectivist interpretation of their results (as opposed to the realist-distributivist interpretation). We argue that a thorough analysis of both their data and our new findings shows a rather wide range of differing intuitions among laypeople regarding the status of groups as agents. These results show that while some laypeople may have realist-collectivist intuitions, the contrary realist-distrubutivist intuitions are also widespread and the claim that the majority of laypeople hold collectivist intuitions regarding group agency is unjustified.

In Sects. 2 and 3, we introduce the main metaphysical stances on collective agency and intentionality and the role of an appeal to intuition in arguments presented in the debate between the proponents of these views. In Sect. 4 we argue that experimental research is needed to resolve these issues and point to the findings concerning the GKE as promising in this regard. We hypothesize that the GKE may also be present as its epistemic and doxastic counterparts and argue that observing these effects would strengthen the argument for the intuitiveness of realism about group agency. Furthermore, we discuss M&S’s study (2019) and argue that further investigation and replication of their results are needed to corroborate their conclusion that the existence of the GKE supports collectivism about group agency and intentionality. In Sect. 5, we briefly summarize the research objectives of our replications and extensions of M&S’s study. Sections 6 and 7 are devoted to a detailed presentation and discussion of our new experiments. In these sections, we demonstrate the existence of the GEKE and GDKE as well as critically assess the hypothesis that the results suggest the existence of non-distributive (viz. collectivist) GKE. In Sect. 8, we discuss the limitations of our study as well as the potential implications it brings to the debate regarding collective intentionality. Additionally, we attach two appendices containing the details of particular analyses.

2 Metaphysical accounts of group agency

Can groups perform actions and take responsibility for their consequences? If so, in what sense? Apart from being described as acting and responsible, can a group also be described as possessing beliefs, intentions, and desires? These questions are widely debated in social philosophy and metaphysics, and one’s answer to them determines their philosophical position in the debate on collective agency and intentionality.

The first line of division may be drawn between those who believe that groups possess agency and intentional states anyhow conceived and those who deny groups these properties; we may label the first position realism and the second position irrealism. Irrealist stances, although not very popular among theorists of collective agency, are still very much present in the sociological school of methodological individualism, which emerges from the writings of Max Weber (1922) and was later defended by, for example, Karl Popper (1957), John Watkins (1952), and Friedrich von Hayek (1942), while its more modern applications to the philosophical problem of collective responsibility might be encountered in Sverdlik (1987) and Corlett (2001). In the discussion concerning the possession of propositional attitudes by groups, one can easily encounter theses that at least imply irrealism, such as materialist or reductionist views in philosophy of mind as expressed, for example, by Alvin Goldman (2002, p. 179): “Knowers are individuals, and knowledge is generated by mental processes and lodged in the mind-brain”.

But even if we agree that a group indeed may possess beliefs, undertake actions based on its intentions, and take responsibility for them, we are still allowed to ask whether the group possesses these characteristics as a group qua group or as a group qua the members of the group? Or to put it differently: is possession of some propositional attitude P by a group a fact reducible to some combination of propositional attitudes Q1,…, Qn held by the members of such a group?Footnote 1 A negative answer to this question has been endorsed by Margaret Gilbert (1989), Christian List and Phillip Pettit (2011), and Deborah Tollefsen (2002, 2015), while the positive has been endorsed by Michael Bratman (1999) and Raimo Tuomela (2007, 2013). We may label the former view collectivism (according to which groups-qua-groups are intentional agents) and the second distributivism (according to which groups are intentional agents only qua-its members).

It is worth stressing that realism concerning collective propositional attitudes and collectivism are not synonymous. The realist believes that group propositional attitudes exist, while the irrealist denies it, but the question of how these attitudes are brought into existence is a different matter. We take the collectivism–distributivism division as a division within the class of realist views. Irrealists deny the existence of group propositional attitudes altogether (they would charge the phrase “the jury finds NN guilty” of being categorically fallacious). Distributivists, in our understanding, defend the view that there are group propositional attitudes (hence, distributivists are realists), but they are reducible to the attitudes possessed by individual members of the respective group, and hence there is no need to postulate groups as independent intentional agents. Distributivists usually appeal to the existence of a specific mode in which individuals’ beliefs or intentions are formed, which grounds the emergence of collective action or belief, such as “joint intentions” or “we-intentions” of individual group members. Collectivists, on the other hand, believe that collective attitudes are irreducible and therefore need to be explained by the existence of groups as independent intentional agents. “Agency” is here usually understood in one of the following ways: either interpretationist (groups are agents since they fulfill necessary conditions of being interpreted as such; e.g., List & Pettit, 2011; Tollefsen, 2002) or functionalist (groups are agents since they fulfill the functions identified with intentional agency; e.g., Epstein, 2015; Huebner, 2013; Strohmaier, 2020).

3 Intuitions about group agency

We should acknowledge that many of the recurring arguments in the debate on collective intentionality and agency are predicated on the perceived intuitiveness of certain philosophical views. Many irrealists regarded talk of collective agency and intentionality as absurd, as evidenced by Ned Block’s (1980) famous China Brain argument, where the hypothesis that the nation of China can possess intentional states or consciousness is treated as a reductio ad absurdum of functionalist accounts in the philosophy of mind. Among similar recurring objections against realism, one may also find the view that collective propositional attitudes and agents are “spooky entities” created by “magic” (see: Searle, 1995; Thomasson, 2019). The assumption behind this objection is that the existence of such entities is contrary to commonly shared intuitions.

This assumption, however, can easily be challenged by an appeal to a different class of intuitions. The talk of collectively held propositional attitudes is indisputably widespread in both everyday discourse and in legal and moral contexts. We seem to say of certain groups—organizations, nations, collectives—that they possess certain beliefs (“The jury finds the accused guilty…”), intend or plan to undertake certain actions (“Amazon plans to cut its employment…”), and enjoy certain feelings (“FC Barcelona mourns the departure of Leo Messi…”Footnote 2). Such constructions may be used to support the claim that folk psychology indeed grants propositional attitudes to at least some groups (Tollefsen, 2002). On the other hand, while the proponents of collectivism may appeal to the existence of linguistic constructions such as those mentioned above, the distributivists and irrealists would respond by claiming that such sentences are “plainly metaphorical” (Quinton, 1975, p. 17; see also: Tuomela, 2007, p. 145). Therefore, the question of whether realism or irrealism, or which of the realist views (collectivism or distributivism), is intuitive and presupposed by folk psychology—and which is revisionary—is still not settled.

According to Peter Strawson’s (1974) requirement that philosophical conceptions of morally loaded concepts shall not be too radically divorced from human needs and interests—unless their proponents provide some theory justifying philosophical revisionism—it is important for this debate to find out what is common-sensical and intuitive for ordinary people about group agency, and what is revisionary. Claims about intuitiveness, in turn, ought to be supported by empirical evidence about what people actually think. The experimental investigation of folk-psychological intuitions concerning group actions and cognitive abilities is thus an important aspect of assessing the philosophical plausibility of theories of collective intentionality and group agency.

4 Experimental data concerning folk intuitions about group agency

Testing common intuitions regarding sophisticated philosophical topics is not a straightforward matter. Asking people directly about collectivism and distributivism would not work for obvious reasons: it would test their philosophical literacy rather than actual intuitions about group agency. What is needed is some indirect measure that would plausibly reflect the relevant intuition. An interesting measure has been proposed by John Andrew Michael and András Szigeti (2019). These authors make use of the widely known side-effect effect [Knobe (2003) the Knobe Effect (KE)], which consists of higher attributions of intentional agency and moral responsibility in a case where an agent’s action leads to negative consequences than in a case where it leads to positive consequences. M&S presented their subjects with cases which were aimed to test whether the KE will obtain when the questions concern the intentionality of an action and its blame/praiseworthiness (BP-worthiness), not of some individual (as in Knobe [2003] and its numerous replications) but of a group. The expected asymmetry—the authors labeled it “the Group Knobe Effect” (GKE)—is supposed to reveal realist intuitions. For if subjects perceive group agents similarly to individual agents when it comes to the ascription of intentionality or responsibility for side-effects of their action (GKE), a strong abductive argument for the claim that the folk tend to hold realist intuitions about group intentionality and responsibility is available. Namely, the hypothesis that the folk are realists about group intentional action is simply “the best explanation” of the existence of the GKE (at least until these philosophers who claim that realism is counterintuitive could come up with some alternative explanation for the existence of the GKE).

4.1 The Group Knobe Effect as a measure of the intuitiveness of group agency: Introduction of doxastic and epistemic Knobe Effects

There are two problems with the GKE as a measure of intuitions concerning group agency.

The first problem is that, as indicated in the introduction to this section, the GKE features in the abductive argument for collective intentionality and group agency in such a way in which it shows parallelism of intentionality ascriptions to individuals and to groups. Therefore, the GKE would actually measure people’s readiness to attribute intentional agency to groups only if the regular KE actually measured people’s readiness to attribute intentional agency to individuals; that means, if the regular KE can be obtained only with respect to intentional agents. If, on the contrary, obtaining the KE is independent of whether the protagonist is an intentional agent, the reasoning towards group agency would not stand.

The claim that the KE obtains with respect to intentional agents is widely assumed by various analyses of the KE, which explain this effect by the folk-psychological mechanisms of belief attribution or characteristics of a folk concept of intentional action (see, e.g.: Alfano et al., 2012; Feltz, 2007; Knobe, 2006; Paprzycka-Hausman, 2020). However, there is another possibility that contradicts this claim: an interpretation of the KE as a merely linguistic effect, not grounded by mechanisms of intentional attribution (Cova, 2015).Footnote 3 A recent study that might support this interpretation was carried out by Masaharu Mizumoto (2018). He conducted a survey without any vignettes—the participants were asked merely about correctness, naturalness, or wrongness of intentionality adverbs accompanying certain verbs—and he found that the KE still holds (varying in strength and character depending on the language in which the survey was conducted and the particular “intentionality adverb” chosen). Effectively, the KE can be thought of as a linguistic default, “independent of any particular background or context, like how that action or event is caused and the details (in particular, the mental state) of the agent mentioned in it” (Mizumoto, 2018, p. 1626). While, as Mizumoto (2018, p. 1626) acknowledges, “this does not rule out the accompanying psychological effect”, it certainly does cast doubt on whether ascribing intentional states to groups remains “the best explanation” of the existence of the GKE, since the GKE, just like the individual KE, might follow by default from the linguistic parameters of the expressions involved in the survey.

However, in his study, Mizumoto (2018, p. 1628) provides evidence only of the KE obtaining without any vignette in the case of the term “intentionally” and its Japanese counterparts, while he explicitly states that it is improbable that the KE will obtain without any vignette if we replace “intentionally harmed/helped” by terms such as “knew”, “caused”, or “allowed”. If he is right,Footnote 4 there is still some space for KE as a reliable measure of actual attribution of mental states to the protagonists of the scenarios, only the KE has to be obtained with the use of these other terms. Accordingly, further investigation into the GKE would strengthen our measure and confirm that obtaining the GKE tells us something interesting about the folk concept of group intentionality—provided we use these other terms.

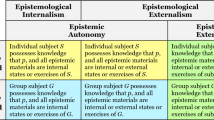

Fortunately enough, the tools are ready. While Knobe’s original investigation concerned only attributions of the intentionality of an action and its moral evaluations, further studies have shown that the asymmetry may also be observed in attributions of knowledge (Beebe & Buckwalter, 2010; Beebe & Jensen, 2012) and belief (Beebe, 2013). With respect to individuals, subjects are more eager to ascribe belief and knowledge of the consequences of one’s actions if these consequences are perceived as negative. We will dub it Doxastic Knobe Effect (DKE) and Epistemic Knobe Effect (EKE), respectively.Footnote 5 While the existence of the regular KE, according to Mizumoto’s findings, need not indicate any actual attribution of an intentional state, the EKE and DKE may be viewed as features of actual folk attribution of intentional states: knowledge and belief.

Now, if realism about group propositional attitudes is indeed a feature of folk psychology, we may expect the presence of Group Epistemic and Doxastic Knobe Effects (GEKE and GDKE). Thus, observing GEKE and GDKE would provide us with good abductive reasons to believe that an evaluation of the decision made by the protagonist in the vignette (here: a group agent) actually involves the processes of ascription of intentional states. Since both EKE and DKE are obtained by asking straightforward questions concerning the possession of belief or knowledge by the protagonist, it would be odd to find out that answering them is not guided by any meaningful reflection on whether an agent in question is capable of possessing beliefs and knowledge. If we find that both GEKE and GDKE obtain similarly to individual EKE and DKE, it will provide us with a convincing argument that people ascribe beliefs and knowledge to groups in an analogous way as they do to individuals.

The second problem is that people may attribute propositional attitudes to groups-qua groups or groups-qua the members of the groups, which correspond to two different phenomena: non-distributive and distributive GKE, respectively. Distributive GKE is an interpretation of the GKE “as merely the aggregative result of ascriptions of intentions and praise/blame to several individuals” (Michael & Szigeti, 2019, p. 48). Non-distributive GKE would involve no intermediate reasoning in the process of intention, moral blame, knowledge, or belief ascription to groups; it would rather apply directly to groups as intentional agents. This raises the question whether potential group effects, if found, would indicate a collectivist (scil. non-distributive) or merely distributivist version of realism towards group agency. In order to support the claim that the folk are collectivist about group agency, we need to show that the GKE (including GDKE and GEKE), as observed, is non-distributive. What needs to be done is therefore obtaining the GKE in a way that is incompatible with the distributive interpretation.

4.2 Summary and evaluation of Michael and Szigeti’s findings

Michael and Szigeti (2019) conducted the first study of GKE (a set of experiments focused on folk intuitions about group agency in Knobe-like scenarios). The study consists of a series of experiments, of which we take Experiment 4 and Experiment 2b to be the most informative.Footnote 6 In particular, the results of Experiment 4 are considered by the authors themselves as the strongest evidence for non-distributive GKE.

In their study, the participants were assigned either to a Harm condition or a Help condition and presented accordingly with a Harm/Help vignette:

ACME Inc. started a new program. When launching the new program, data suggested that the program would help ACME Inc. increase profits, but that it would also [harm/help] the environment. In line with ACME Inc.’s business policies and in the interest of maximizing profits, the new program was implemented. Sure enough, the environment was [harmed/helped].

Then, the participants responded, first, to the intention question: “On a scale from 0 to 8, to what extent would you agree that ACME Inc. intentionally [harmed/helped] the environment? (0 = disagree strongly, 8 = agree strongly)”; and second, to the blame/praise question: “On a scale from 0 to 8, how much [blame/praise] do you think ACME deserves for [harming/helping] the environment? (0 = no [blame/praise] at all, 8 = maximum [blame/praise])” ( Michael & Szigeti, 2019, pp. 54–55).

The experiment revealed clear evidence of the GKE in folk intentionality ascription and moral evaluation practices. It does not mean, however, that the folk treat groups non-distributively when ascribing intentionality and moral responsibility to them. According to our considerations in the preceding section, this question cannot be resolved solely based on the results of this experiment. All that is proven by obtaining the GKE in this scenario is that people do attribute propositional attitudes to groups; nothing is established as to how they do it. In opposition to collectivism, distributivists are likely to point out that intentional states ascription in this case may be provided by reasoning about the intentions or beliefs of certain members of the group in question. Although intentional states may be ascribed to groups by the folk—Experiment 4 clearly corroborates general realist intuition among participants—it does not necessarily mean that these states are attributed to a group-qua group (i.e., non-distributively).

What is worth noting about Experiment 4 is that the group agent in question is a corporation. In the philosophical considerations of collective intentionality, a corporation is a nearly paradigmatic case of a group that may possess intentional states (Hess, 2014). Collectivists who frame their position as a kind of interpretationism would argue that corporations may be truly ascribed beliefs, desires, and intentions precisely because corporations may undertake certain institutional actions that may be interpreted with the use of folk-psychological vocabulary. These collectivists who take a functionalist approach towards collective intentional states will likely point out functional roles played by committees, boards, or other hierarchical structures that may be sufficient for the emergence of intentional states. Michael and Szigeti (2019, p. 54) in a similar fashion invoke evidence that “corporations are consistently given high entitativity ratings by people and that in general corporations are particularly likely to be perceived in non-distributive terms by ordinary folk (as well as by lawyers and philosophers)”. There are, however, some problems with such a straightforward interpretation, since questions concerning the beliefs or intentions of some corporations may be easily understood as an indirect form of asking about propositional attitudes held by some members of this group (e.g., members of the board, the CEO, or a spokesperson). To see whether laypersons distinguish between collective attitudes and the attitudes of members of the collective, we need to carefully differentiate between direct and indirect ascription of collective intentional states and put them to empirical test.

Michael and Szigeti (2019, p. 49) claim that the presentation of non-distributive GKE is the goal of all experiments from 2 to 4 in their study; however, as we explained above, at least Experiment 4 does not meet the general criteria of inaccessibility of distributive interpretation. To test the hypothesis that people not only ascribe intentionality and propositional attitudes to groups, but do so non-distributively, we need to examine M&S’s Experiment 2b, which, in our opinion, is the closest to an experimentum crucis for the hypothesis that the GKE may obtain non-distributively.

In M&S’s Experiment 2b, in a 2 × 2 between-subject design, the participants were randomly assigned to a pair of conditions: Harm/Help—similarly as in the previously discussed Experiment 4—and Support/Dissent, which introduced a new experimental manipulation. In the Support condition, subjects were told that the individual members of the board who were supposed to decide as to whether to start the new program (that will either help or harm the environment, depending on the Harm/Help condition) personally supported the program, while in the Dissent condition, participants were informed that the members of the board opposed the program, but nevertheless had to implement it due to some institutional policies. The vignette (Michael & Szigeti, 2019, p. 51) is presented below:

Representatives from the research and development department of a company reported to the board and said, “We are thinking of starting a new program. It will help us increase profits, [but/and] it will also [harm/help] the environment.” The board consisted of three members: Benson, Franklin and Sorel. [For various reasons, each of them personally opposed the program and tried to prevent it from being implemented. However]Dissent/[Each of them personally supported the program and did not object to its being implemented. In any case]Support, they were obliged to follow the board’s standard decision-making protocol, which left no opportunity for their personal views to influence the decision. As a result, in line with the company's business policies and in the interest of maximizing profits, the new program was implemented. Sure enough, the program was highly profitable and the environment was [harmed/helped].

After reading the vignette, the subjects were asked questions similar to those discussed above in our description of M&S’s Experiment 4. However, besides answering questions about the board’s intentions and BP-worthiness, the respondents were also asked analogous questions about the individual members of the board: their intentions (e.g., “On a scale from 0 to 8, to what extent would you agree that Benson, Franklin, and Sorel intentionally harmed the environment?”) and BP-worthiness (e.g., “On a scale from 0 to 8, how much [blame/praise] do you think Benson, Franklin, and Sorel deserve for [harming/helping] the environment?”).

The authors reasoned that “if the GKE is distributive, then participants should not be more inclined to attribute intentions or blame- or praiseworthiness to the board than to the individual members, whereas if the GKE is non-distributive, they should be” (Michael & Szigeti, 2019, p. 51). We agree with this reasoning. Such a result—let us call it the Target Effect—is supposed to show the contrast between the ascriptions of intentionality to the board and to the members of the board in a given set of conditions: harm–support, harm–dissent, help–support, and help–dissent. In the absence of other disturbing effects, some of which we will discuss below, it would indeed suggest a non-distributive reading of exhibited GKE. However, the problem is that M&S did not calculate and explicitly discuss this particular effect. The Target Effect might be only indirectly and partially deduced from their ANCOVA analysis which is only mentioned briefly by M&S (for details, see Appendix 1). We believe that the Target Effect deserves more careful examination and we will offer an approach that investigates the Target Effect in a more up-front manner.

Instead of putting stress on the Target Effect, M&S focused on two different types of distinctions. First, they analyzed the distinctions between Harm condition and Help condition separately for the board and the members of the board. Second, they analyzed the distinctions between Support condition and Dissent condition, again separately for the board and the members of the board. Neither of these analyses reveals the Target Effect or supports the non-distributive interpretation of the GKE. The former indicates just the GKE in general, without specifying its non-distributive character. The latter reveals another effect, quite interesting, albeit unnoticed by M&S, which we will call the Hypocrisy Effect.

4.3 The Hypocrisy Effect

The essence of the Hypocrisy Effect (HE) is that if you demonstrate your personal dissent when doing something, people think of your action as less intentional and are less likely to blame/praise you for it than they would have, had you demonstrated your support.Footnote 7

Typically, the HE concerns the individual level: it is individual members who get acquitted from the blame for the group actions, provided they have expressed their dissent. The Group HE would also be intelligible, provided it was the group that expressed relevant dissent from its own actions (e.g. through an official disclaimer), not any of its individual members.Footnote 8 However, M&S have not advanced any attempt towards exploring this effect (in particular, they didn’t consider the option that the board qua board issued a statement of dissent/support towards its own proceedings). Neither have we in our extensions of M&S’s experiments, and for a straightforward reason: GHE, just as GKE, by itself would not indicate whether the group attribution is distributive or non-distributive. It would just add to corroboration of general realism towards groups, a stance we already find well corroborated.

However, it is the individual HE that can be used as an indicator of distributive or non-distributive way of attributing intentionality to groups; albeit in an indirect and elaborate way. In the setting of the M&S’s study, the HE reveals itself in a twofold way: as the difference between intentionality ascriptions in the support condition and in the dissent condition for the board—and as the difference between intentionality ascriptions in the support condition and in the dissent condition for the individual members of the board. Note that neither difference shows the GHE—for there is nothing said about official disclaimers from the board as the whole. All we have got in both cases is information about individual dissent/support of the members of the board (thus both ways we get a variant of the individual HE). But the comparison of these two cases can be informative about the distributive/non-distributive interpretation of groups.

We hypothesize, namely, that the HE should not appear for a group taken collectively, when it is only the members of the group who express their personal dissent/support. The appearance of the individual HE in groups is understandable when the groups are taken distributively, that is as the aggregations of their members. In such a case acquitting the members from guilt would automatically acquit the group, even if it is only the members who express their dissent. Thus, the occurrence of the HE for the board in M&S’s setting would undermine a collectivist reading, while the absence of the HE for the board, accompanied by a noticeable HE on its members, would—abductively—indicate a collectivist reading.

And indeed, a weak suggestion in this direction appeared in M&S’s study. Based on M&S's data (see Appendix 1 for details), our analysis revealed a very small-sized HE on the board as a group, accompanied by a small, but relatively larger HE on the members of the board. It means that, while many participants judge the situation in a way coherent with the distributive interpretation, some of them—those who contributed to the appearance of the HE on the members but not on the board—seem to have expressed a non-distributive intuition.

4.4 Summary of the preliminaries

Summing up, it may seem that the results reported by M&S mildly suggest a non-distributive reading. The main indicator of such a reading—the Target Effect—appears somehow in their figures, although it is not discussed properly. A very small Hypocrisy Effect concerning the group agent, compared with relatively larger HE concerning individual agents, observed in the data, also hints at a non-distributive interpretation.

However, before we jump to the conclusion that the non-distributive interpretation of the GKE has been thus established in M&S’ study, we need to consider another way of looking at the data collected in M&S’s Experiment 2b. The within-subject aspect of their study allows for comparing the ratings concerning the group and its individual members for each participant of the experiment. Not surprisingly, in the Support condition (Harm/Help conditions aggregated), the majority of laypersons (65.7%) gave the same rating when attributing intentionality to the board and the individuals; only 20% were more likely to ascribe intentionality to the group than to its members (which amounts to exhibiting the TE), in line with the non-distributive reading. What is surprising, though, is that the picture is not radically different in the Dissent condition, where nearly half of the subjects (48.3%) did not differentiate between the board and its individual members when attributing intentionality. Target Effect would emerge from only 34.3% of answers which expressed non-distributive intuitions (i.e., agreed more with the intentionality ascription when assessing the group than when assessing the individuals). Any differences in HE, between the group ascriptions and individual ascriptions, were only exhibited by a small number of participants in M&S’s study, too.

In conclusion, the non-distributive reading of the GKE, while mildly suggested, is by no means established thus far. Therefore, although we believe that the way in which Michael and Szigeti approached the data is sound, we recognize the need for enhanced studies, which could substantiate the verdict more robustly. As indicated in Sect. 4.1, we consider it necessary to both focus properly on the distributive/non-distributive distinction and provide further evidence for the intentional nature of the GKE (against the linguistic interpretation of the effect provided by Mizumoto).

5 Research objectives

The main aim of our study was to find out whether laypeople exhibit intuitions that are in line with the realist account of group agency. In the spirit of M&S’s (2019) argumentation, we assumed that the occurrence of the Group Knobe Effect (concerning various mental state ascriptions) would provide evidence of such intuitions. We expected to corroborate the original findings reported by M&S regarding intentionality attributions and to find evidence of Group Epistemic and Doxastic Knobe Effects, which yields the following hypotheses:

(H1) The pattern of folk intentionality attributions will exhibit the Knobe asymmetry (subjects will be more likely to ascribe intentionality to both individuals and groups in the Harm condition than in the Help condition, in line with the findings reported by M&S).

(H2) The pattern of folk knowledge and belief attributions will exhibit the Knobe asymmetry (participants will be more likely to ascribe knowledge and belief to both individuals and groups in the Harm condition than in the Help condition, which would be evidence of Group Epistemic and Doxastic Knobe Effects).

We were also interested in establishing whether, if H1 and H2 bear out, the side-effect effects in question stem from distributivist or collectivist intuitions. Based on the conclusions drawn by M&S from their data (see Sect. 4.2), we hypothesized that:

(H3) Realist intuitions concerning group agents’ intentions, knowledge, and beliefs exhibited by laypeople will be in line with the collectivist interpretation (the Dissent/Support manipulation will have a bigger impact on subjects’ ratings about individuals than their judgments about groups; i.e., the Hypocrisy Effect (i. e., laypersons’ tendency to attribute intentional states to a lesser degree when the agent in question expresses their dissent towards the performed action) will be noticeably stronger for ratings concerning individuals than for ratings regarding group agents).

We tested our hypotheses in two experiments presented in the following sections.

6 Study 1: Replication and extension of M&S’s Experiment 4

Our first study was a replication and extension of Experiment 4 conducted by Michael and Szigeti (2019). We chose to replicate this experiment first because, according to M&S, it was the most straightforward way of putting the hypothesis about the GKE to test among the studies they carried out.

6.1 Methods and procedure

The study adopted similar methods as the original experiment by M&S but included two additional measures for the sake of testing GEKE and GDKE: questions about belief and knowledge. We adopted a simple between-subjects design with one dichotomous independent variable (Harm/Help condition). Each subject was randomly assigned to one of the two conditions and presented with one of the two variants of the story phrased exactly as in the original study.

The order of presentation of questions regarding the vignette was identical for all the subjects. First, they were asked about intentionality (On a scale from 0–8, to what extent would you agree that ACME Inc. intentionally [harmed/helped] the environment?; where 0 = “disagree strongly” and 8 = “agree strongly”), and then they were asked about blame/praise (On a scale from 0–8, how much [blame/praise] do you think ACME deserves for [harming/helping] the environment?; where 0 = “no [blame/praise] at all” and 8 = “maximum [blame/praise]”), which is the same order as in the original study. Then every subject was presented with the prompt concerning knowledge (On a scale from 0–8, to what extent would you agree that ACME Inc. knew that it was [harming/helping] the environment?; where 0 = “disagree strongly” and 8 = “agree strongly”) and belief (On a scale from 0–8, to what extent would you agree that ACME Inc. believed that it was [harming/helping] the environment?; where 0 = “disagree strongly” and 8 = “agree strongly”). Only the edge points of the scales were labeled. Each measure was presented on a separate screen, and the participants could not change their preceding answers.

Additionally, every subject was asked a simple comprehension question that followed all the crucial measures and was supposed to check whether the participants read the scenario carefully enough. In both conditions, it was as follows: Did ACME Inc. implement the program? The respondents could choose from three options (“Yes”, “No”, “I don’t know”), and only those who answered “Yes” were included in the final analysis. After reading the vignette and answering all the questions concerning the scenario, each subject completed a short demographic survey (participants were asked about their gender, age, religion, ethnicity, and education). The study was conducted as an online survey designed using LimeSurvey (an open-source survey application: www.limesurvey.org), and it was posted on servers owned by KogniLab (University of Warsaw X-Phi Laboratory, www.kognilab.pl). The datasets with the results of both this and the subsequent study can be accessed online via Open Science Framework webpage: https://osf.io/b7nj3/.

6.2 Participants

The respondents were recruited from the population of Amazon MTurk workers located in the USA and were native English speakers. Every subject received a small financial compensation for taking the survey. A total of 306 participants completed the survey, but 17 of them did not provide a correct response to the comprehension question, so the final sample size was N = 289 (140 in the Harm condition and 149 in the Help condition). 55.7% of the participants were male, 41.5% were female, and 2.7% indicated they were non-binary or chose not to disclose their gender. Their average age was 38.45, with SD = 12.53 (two participants did not provide valid information concerning their age).

6.3 Results

For each measure included in our first study (intentionality, BP-worthiness, knowledge, belief), we ran separate independent samples t-tests to compare average ratings provided by the subjects in the Harm and Help conditions. Our analysis found significant differences between conditions in the predicted direction in each case. Subjects were more likely to say that ACME intentionally harmed the environment (M = 6.55; SD = 1.62) than that ACME intentionally helped the environment (M = 5.21; SD = 2.05): t(287) = 6.15; p < 0.001; d = 0.73. Similarly, participants judged that the corporation deserves more blame in the Harm condition (M = 6.84; SD = 1.53) than praise in the Help condition (M = 5.33; SD = 2.0): t(287) = 7.16; p < 0.001; d = 0.85. These results corroborate previous findings reported by M&S about the GKE regarding intentionality of actions and moral judgments about actions. Moreover, we found support in favor of our additional hypothesis about the existence of the GEKE and GDKE; our subjects attributed knowledge to ACME corporation more willingly in the Harm condition (M = 6.81; SD = 1.52) compared with the Help condition (M = 5.96; SD = 1.78): t(287) = 4.38; p < 0.001; d = 0.51. And lastly, their judgments about ACME’s beliefs were analogous; belief attributions were higher in the Harm case (M = 6.69; SD = 1.54) than in the Help case (M = 6.1; SD = 1.77): t(287) = 3.02; p = 0.003; d = 0.36. Our results are illustrated in the Fig. 1.

Our results confirmed our expectations—we successfully replicated Experiment 4 originally conducted by Michael and Szigeti (2019) and extended their result by finding a group variant of the EKE and DKE. However, we think it is worth noticing that the sizes of the effects we observed were smaller than those obtained by M&S.Footnote 9 This, of course, does not mean that they are theoretically unimportant (especially that we cannot claim that our estimation of the real effect size is more accurate than what M&S reported). Nevertheless, small but well-established effects are still of importance for philosophical theorizing.

6.4 Discussion

Our results confirm the existence of the Group Knobe Effect as described by M&S as well as present evidence for the existence of its epistemic and doxastic counterparts. As discussed above, this provides us with more compelling evidence that people are likely to ascribe intentionality of action as well as knowledge and beliefs to groups analogously to how they ascribe these states to individuals. To address the possible worries that the mere occurrence of the GKE would not support this thesis strongly enough, the additional demonstration of Epistemic GKE and Doxastic GKE provides wider encouragement to the idea that these ascriptions involve folk-psychological mechanisms of attribution of propositional attitudes. However, this does not mean by itself that groups are evaluated qua groups—that is, non-distributively—since we gathered no data on whether people came to this attribution via hypothesizing about propositional attitudes held by some members of the group in question. We believe that the demonstration of a considerable effect in the predicted direction should be counted as an occurrence of the GKE, GDKE, and GEKE, although our results should be approached carefully and encourage further inquiry concerning the real size of the effects in question.Footnote 10

7 Study 2: Replication and extension of M&S’s Experiment 2b

In our second study, we employed methods similar to those used in M&S’s Experiment 2b (which, again, sought evidence for the GKE). Additionally, we extended the procedure to investigate GDKE and GEKE (i.e., we asked our participants about their intuitions concerning belief and knowledge). In our opinion, M&S’s Experiment 2b was their best attempt to settle the question of whether the GKE they observed was distributive or collective, and, by inheritance, we thought that our extension regarding the GEKE and GDKE would also allow us to decide whether the evidence for GEKE and GDKE that we found in our first experiment stemmed from collectivist or distributivist intuitions.

7.1 Methods and procedure

We employed a 2 × 2 between-subjects design with the following factors: Harm/Help (the standard Knobe-style manipulation) and Support/Dissent (similarly as in M&S’s Experiment 2b). The materials and experimental manipulations were identical to the original study (see Sect. 2.4 for details), as well as the questions addressed to the participants. The only difference in the procedure was the fact that we also included questions regarding beliefs and knowledge for both the group agent (e.g., On a scale from 0–8, to what extent would you agree that the board knew that the environment will be harmed?) and the individual members of the board (e.g., On a scale from 0–8, to what extent would you agree that Benson, Franklin, and Sorel knew that the environment will be harmed?). Each question was presented on a separate screen in a fixed order (intentionality—moral responsibility—knowledge—belief); the first set of questions concerned the board, while the second set concerned the individual members of the board. Our subjects had no opportunity to go back in the survey and change their preceding answers; the scenario was presented at the top of the screen with each consecutive question.

7.2 Participants

All the subjects who participated in the study (N = 797) were recruited via Amazon MTurk and received small financial compensation for filling out the survey. However, we excluded 147 responses from the analysis, so the final sample size was N = 650 (Harm: n = 335; Help: n = 315; Dissent: n = 329; Support: n = 321). The subjects we included in our analysis were native English speakers who resided in the USA and passed the attention check we employed in this study.Footnote 11 Fifty-two percent of respondents were male, 47.1% were female, and 0.9% chose the option “non-binary” or “other”. The average age was 40.08 (SD = 12.49), ranging from 18 to 75 years.Footnote 12

7.3 Results

We approached our data in a similar manner as M&S: we conducted separate 2 × 2 ANOVA analyses for each measure included in the study (intentionality attribution, moral judgment, knowledge, and belief ascription). Let us first focus on our results concerning intentionality ratings. Here, our results corroborate M&S’s evidence in favor of GKE: we found a significant impact of Harm/Help manipulation on subjects’ judgments regarding the intentionality of the board; on average, more intentionality was attributed to the board in the Harm condition (M = 5.85; SD = 2.28) than in the Help condition (M = 4.36; SD = 2.6): F(1, 646) = 64.69; p < 0.001; η2 = 0.091. We also observed that the Dissent/Support factor affected participants’ answers: they were more likely to attribute intentionality to the board when the individual members supported the decision (M = 5.76; SD = 2.08) than when they opposed it (M = 4.52; SD = 2.81): F(1, 646) = 44.56; p < 0.001; η2 = 0.065. There was also a small but significant interaction between the two factors—F(1, 646) = 5.02; p = 0.025; η2 = 0.008—which resulted from the fact that the size of the GKE was bigger in the Dissent condition than in the Support condition.

The pattern of results for subjects’ judgments concerning the individual members of the board was extremely similar to what we observed for the intuitions about the group agent. There was a significant KE: F(1, 646) = 68.2; p < 0.001; η2 = 0.095Footnote 13; a main effect of Dissent/Support manipulation: F(1, 646) = 95.6; p < 0.001; η2 = 0.129Footnote 14; and a barely significant interaction: F(1, 646) = 4.12; p = 0.043; η2 = 0.006.Footnote 15 Once more, the size of the KE was somewhat smaller in the Support condition than in the Dissent condition. The results are summarized in the Fig. 2.

Since our primary research interests did not focus on the judgments concerning BP-worthiness, we do not present a detailed analysis of this data here (it can be found in Appendix 2); let us just say that our results were highly consistent with the original findings of M&S.

The following analyses concern GEKE and GDKE, so they focus on the new measures included in our extension of the original study. When it comes to knowledge ratings, the picture is again similar to what we found for intentionality judgments, but the sizes of some effects are considerably smaller. For the knowledge attributions regarding the group agent, we observed a significant main effect of Harm/Help manipulation: subjects were more happy to ascribe knowledge in the Harm condition (M = 7.16; SD = 1.37) than in the Help condition (M = 5.92; SD = 1.84): F(1, 646) = 96.78; p < 0.001; η2 = 0.13. However, the main effect of the Dissent/Support factor we found was noticeably smaller but significant: participants were slightly more likely to attribute knowledge in the Support condition (M = 6.69; SD = 1.52) than in the Dissent condition (M = 6.42; SD = 1.9): F(1, 646) = 4.56; p = 0.033; η2 = 0.007. An interaction between the two factors also emerged: F(1, 646) = 9.997; p = 0.002; η2 = 0.015; and, once more, it appeared because the GEKE we observed was larger in the Dissent condition than in the Support condition.

The analysis performed on knowledge attributions to individual members of the board yielded, by and large, similar results. We found strong evidence of EKE: F(1, 646) = 119.58; p < 0.001; η2 = 0.156Footnote 16; a noticeably smaller impact of the Support/Dissent factor on knowledge ratings: F(1, 646) = 7.84; p = 0.005; η2 = 0.012Footnote 17; and an interaction effect, for the same reasons as in our previous analyses: F(1, 646) = 15.29; p < 0.001; η2 = 0.023. The data regarding knowledge attributions we collected are summarized in the Fig. 3.

Since the distribution of answers across experimental conditions was almost identical for the belief attributions and knowledge ratings, we will not present a detailed analysis of the belief measure here, but only illustrate the results with the following figure (more information is provided in Appendix 2) (Fig. 4).

Additionally, we performed a series of ANCOVA analyses for the crucial measures—attributions of group intentionality, knowledge, and belief—that included the judgments concerning the individual members of the group as covariates. This procedure was used by M&S to show that the GKE they observed cannot be reduced to the regular KE we observe for attributions of intentionality to individuals, and to support the hypothesis about the non-distributive nature of the GKE. And as far as the GKE is concerned, we obtained a similar result as M&S: in our experiment, there was a significant impact of the Harm/Help manipulation on subjects’ intentionality attributions to the group agent, even when we controlled for their ratings concerning the individual members of the board: F(1, 647) = 11.75; p < 0.001; η2 = 0.018. It is worth noting, however, that the size of this effect is considerably smaller than what the standard ANOVA analysis revealed (η2 = 0.018 vs. η2 = 0.091). The situation for the knowledge and belief measures is analogous, as both ANCOVA analyses found a significant but small GEKE and GDKE for knowledge ratings: F(1, 647) = 8.78; p = 0.003; η2 = 0.013; and for belief ratings: F(1, 647) = 8.97; p = 0.003; η2 = 0.014.

Significant results of the ANCOVA analyses reported above indicate that the Knobe-style asymmetries we observed for laypersons’ intuitions concerning group agents cannot be reduced to their intuitions regarding individual members of the groups in question. To put it differently, we found some evidence of the non-distributive GKE, GEKE, and GDKE, which, to some degree, confirms our third hypothesis (H3); however, the sizes of those effects were rather small, and we believe that the data deserve more consideration before one draws conclusions as to whether the non-distributive intuitions about group agents are sufficiently widespread among the folk to be theoretically interesting. Also, the fact that including ratings concerning the individual members of the board as covariates in the analysis of judgments about the group agent resulted in a considerable drop in the size of the observed effects indicates that the distributive interpretation is well suited to explain the intuitions exhibited by a large group of our subjects.

If we compare subjects’ intentionality ratings concerning the group agent and the individual members of the board across all the experimental conditions (similarly as we analyzed M&S’s original data in Sect. 4.2), we can find evidence of the small-sized Target Effect we are seeking; our respondents were, on average, more likely to attribute intentionality to the group agent (M = 5.13; SD = 2.55) than to its members (M = 4.64; SD = 2.72): t(649) = 5.92; p < 0.001, d = 0.23. We additionally calculated the number of participants who declared a given level of difference between group intentions and individual intentions by subtracting subjects’ ratings regarding individuals from their ratings concerning the group. Positive difference means that the level of intention for the group is higher; negative difference means that the level of intention for the individuals is higher; zero means that there is no difference i.e., the participants assigned the same level of intention to groups and to individuals (the Target Effect does not show). The distribution of this new measure is presented in the Fig. 5.

Thus, although we found significant evidence of the overall Target Effect in intentionality attributions made by our participants—which confirms H3 to some extent—nearly half of the participants rated the intentions of the group and individuals identically, and, surprisingly, it is not only the case in the Support condition but also in the Dissent condition.

Regarding HE (the difference between intentionality attribution in the Support condition and in the Dissent conditionFootnote 18) in our data, we found, interestingly, evidence of HE for both the intentionality ratings concerning the group agent (η2 = 0.065) and the individual members of the board (η2 = 0.129), while in the original data collected by M&S (see Sect. 4.3 and Appendix 1), a significant HE clearly emerged for intentionality attributions to individuals, but for the group it was noticeably smaller.

We thus might summarize our results reported above as follows.

Our replication, as far as intentionality attributions are concerned, reveals a weak Target Effect and a noticeable HE. The HE might seem larger for judgments concerning the board members, but if we look at the 95% CIs for the effect sizes—group: [0.033; 0.104]; individuals: [0.085; 0.177]—we can easily see they overlap, which means there is not enough evidence to claim that one of these effects is bigger than the other. Nevertheless, the HE for the group agent, which never expressed any support or dissent qua group, is definitely noticeable. Additionally, nearly half of the participants would not acknowledge any difference between the board and the members.

A similar analysis can be employed to investigate the nature of GEKE and GDKE that we observed in our data. We present detailed statistics in Appendix 2; here we will only briefly summarize the results. Although we observed significant Target Effects for both epistemic measures included in our study, these effects were rather small (knowledge: d = 0.13; belief: d = 0.14). Interestingly, we also found evidence of a small-sized HE not only for the ratings concerning individuals (knowledge: η2 = 0.012; belief: η2 = 0.025), but also for those regarding the board (knowledge: η2 = 0.007; belief: η2 = 0.014). The proportions of subjects who rated the group agent and its individual members identically when presented with our two epistemic measures were even larger than in the case of intentionality attributions: more than half of our participants did not differentiate between the board and individuals when attributing knowledge and belief, and, once again, only a small group of subjects exhibited collectivist intuitions (i.e., were more likely to ascribe epistemic states to the group agent than to its individual members).

7.4 Discussion

The purpose of conducting this extended replication of M&S’s Experiment 2b was to establish the extent to which Knobe-style scenarios may be used to elicit not only broadly realist but also collectivist intuitions—that is, whether the GKE obtains in a distributive or non-distributive way. In the former case, the realist intuitions regarding group agents would bear down to intuitions concerning the individual members of the group, in the latter, the intuition about group agents would be irreducible. As we noted in Sect. 4.1, merely observing within-subject differences between the intentionality ascription value given to the board and the individuals does not suffice in itself to support the conclusion that the observed GKE was non-distributive. We decided to extend our analysis in two respects we believe are crucial: the first was finding out whether the Target Effect (i.e. the inclination of laypersons to give higher ratings of intentional states regarding the group agent than its individual members) obtains not only for intentionality attributions, but also for knowledge and belief ascriptions. The second was establishing whether the Hypocrisy Effect (i.e. a noticeable drop in intentionality, knowledge, belief and blame ratings in the case when individual members of the group express their personal dissent towards the undertaken action), which suggests a distributive interpretation of folk intuitions concerning group agents, would not diminish the explanatory role of the Target Effect.

Our analysis confirmed the existence of the Target Effect with respect to all ascriptions, which could suggest that a non-distributive reading is available to some laypersons and provide evidence in favor of H3. However, the effect sizes of the Target Effects that we observed were rather small (ranging from d = 0.13 to d = 0.23, depending on the measure). It is also worth noting that by introducing ratings concerning the individual members of the board as covariates in the analysis of judgments about the group agent (ANCOVA analyses), the GKE, GEKE, and GDKE noted a significant drop in size (η2 = 0.018, η2 = 0.013, η2 = 0.012 for intentionality, knowledge, and belief, respectively) when compared to the effect sizes revealed in the simple ANOVA analysis of the group ratings alone. This suggests that the ascription of intentionality, knowledge, or belief to the members of the board did play a role in attributing these states to the board as a group agent, which conforms rather to the distributive reading of the presented scenario. Contrary to M&S’s experiment, as far as intentionality and BP-worthiness judgments are concerned, we also found medium-sized HEs for group agents (η2 = 0.065 and η2 = 0.063, respectively). Moreover, our extension detected small HEs when it came to knowledge and belief ascriptions to the group agent (η2 = 0.007 and η2 = 0.014, respectively). This, as noted in Sect. 3, seems to be at odds with the collectivist interpretation of the data. The dissent of individual members should not influence intentionality, knowledge, or belief ratings given to the board as a group agent under such an interpretation. Therefore, H3 might not be entirely accurate; possibly there are individual differences in intuitions concerning group agency: some laypersons exhibit collectivist, while some exhibit distributivist intuitions.

What also should not be underestimated is the fact that nearly half of the participants rated the intentions, knowledge, and belief of the group and individuals identically. This means that although there might be a group of subjects who possess non-distributive intuitions, they are a minority in the overall sample; therefore, it cannot substantiate M&S’s original conclusion that collectivism is intuitive for the folk. We believe that an overall conclusion should be that collectivist and distributivist intuitions are both present among the folk, and therefore we should abstain from interpreting these results as supporting the claim that collectivism or distributivism is intuitive for the majority.

8 Conclusions

In our concluding remarks, we would like to briefly outline three main contributions of our study for research on folk intuitions concerning group agency and provide more general points about their importance and possible directions for future developments. The first and most straightforward contribution was a high-powered replication of Michael and Szigeti’s (2019) findings which showed evidence that the Knobe Effect generalizes to groups. In this respect, we believe that the results of our experiments, which closely followed the original methodology, corroborate the original findings. The second contribution consists in our extension of M&S’s experiments intended to observe whether Epistemic and Doxastic Knobe Effects, as described by Beebe and Buckwalter (2010) and Beebe (2013), respectively, also generalize to groups. We argued that obtaining such generalizations would strengthen the philosophical significance of intuitions elicited by these experiments since it would provide more robust evidence that the folk’s pattern of ascriptions of intentional states to group agents conforms to the pattern of ascriptions to individuals. Our analyses yielded the predicted results: we observed that the GKE further generalizes to knowledge and belief ascriptions. We argued that both the successful corroboration of M&S’s results concerning the existence of the GKE as well as observing GEKE and GDKE provide strong evidence for the claim that folk are realists about the agency and intentionality of groups. Our third contribution is assessing the claim that the folk are collectivists about group agency—i.e., that the GKE obtains non-distributively. By analyzing both M&S’s original data from their Experiment 2b and our extended replication of it, we determined that their conclusion was rushed in this aspect. Our analyses revealed that, although the effect that supports a non-distributive interpretation of the GKE is present, other significant effects such as the HE support a distributive interpretation. We concluded that our analyses show no evidence for the claim that the folk are collectivist, but rather that the collectivist and distributivist intuitions vary across subjects.

The first two of our conclusions (i.e., that M&S’s findings about the existence of the GKE in general got corroborated and that they generalize to epistemic and doxastic effects) are important as contributions to the empirical study of folk intuitions regarding collective agency and intentionality, as well as the study of the Knobe Effect itself. Popular theories aiming at a uniform explanation of the KE and its epistemic and doxastic counterparts (Alfano et al., 2012; Hindriks, 2014) try to account for it by postulating certain mechanisms of belief and knowledge ascriptions that, in turn, allow the ascription of intentional action and moral responsibility. Our study clearly shows that such models should also take into account heuristics allowing ascriptions of belief and knowledge to at least some groups. Such reasoning leads us to a conclusion that to make sense of this broad pattern of folk-psychological ascriptions of belief and knowledge states, agency, and moral responsibility, one should either accept realism towards collective intentionality and agency or provide an error theory explaining why people tend to use an apparently similar mechanism of ascription when attributing knowledge and agency to individuals and groups. Clearly, irrealism is not intuitive to many people.

Our third conclusion contrasts with M&S’s original claim that the folk seem to be collectivist. We believe that our study provides reasons to believe that neither a distributivist nor a collectivist stance towards collective intentionality or agency should be treated as universally intuitive, but rather both are present among the folk. Although we replicated the main “collectivist” effect of M&S, its importance is severely limited by other phenomena that can be explained by attributing distributivist intuitions to our subjects. However, we do not treat this merely as a negative result. During the course of our analysis, we introduced the Hypocrisy Effect and argued that its presence with respect to ascriptions of intentionality, belief and knowledge to the group agent in Experiment 2b and our extended replication of it, would support the distributive reading (and as such would undermine our H3). This effect is, however, philosophically interesting in its own right. We believe that if, as we argue, folk intuitions about group agency are significantly influenced by the individual support or dissent of its members, then this fact should be accounted for by theories of collective responsibility. For instance, this fact may be used in explanations for why certain groups are less likely to be conceptualized as group agents and held morally responsible for their actions (e.g., crowds or mobs) than others (e.g., corporations or organized forces; see: Held, 1970; Smiley, 2017). Although their harm-inducing potential might be equal, these groups might simply differ with respect to the individuals’ support or dissent towards their actions.

The final words of these conclusions should be devoted to the prospects for future research. Firstly, we think that further investigation of the GKE could include testing other vignettes that are believed to elicit similar asymmetries: morally neutral cases (e.g., the Sales case, Knobe & Mendlow, 2004), cases involving aesthetic consideration (e.g., the Movies case, Knobe, 2004), or cases regarding obedience to discriminatory law (e.g., the Nazi CEO case, Knobe, 2007). Since it was shown that EKE obtains in all mentioned cases (Beebe & Jensen, 2012), extensions regarding the regular GKE as well as GEKE and GDKE could substantiate the claim about the robustness of our findings. Also, since many collectivist and distributivist approaches disagree on the question of which types of groups should qualify as intentional agents (countries, corporations, tribunals, football teams, crowds), it would be important to explore whether the GKE obtains equally strongly with respect to those entities. Lastly, it should be noted that the philosophical importance of the study of the GKE for the collective intentionality debate hinges on the hypothesis that the KE is, at the bottom, a phenomenon concerning ascription of intentional states. A possible way to approach this hypothesis is to examine whether the KE obtains with respect to other objects that are less probable candidates for being intentional agents than groups, such as computers, animals, or inanimate objects. These extensions are, unfortunately, beyond the scope of this paper. We nevertheless believe that inquiring folk intuitions about intentional agency with the use of the KE is a very promising approach.

Notes

Or analogously: is undertaking an action A by the group reducible to some combination of actions B1,…,Bn undertaken by the members of the group?

As noted by one of the anonymous referees, the grammar of this phrase seems to agree with American English, while in British English it would rather be phrased in the plural form: “FC Barcelona mourn…”. This observation may suggest a potential difference between American and British subjects in their perception of the ability of collective agents to enjoy feelings (i.e. phenomenal states in general). This is, however, an issue requiring further study and falls out of the scope of this paper.

By linguistic interpretation of the KE we understand an interpretation according to which this effect results not from applying a certain concept of intentional action to the protagonist in the harm- and help-scenarios, but merely from considering linguistic correctness of the collocations “intentionally helped” and “intentionally harmed”.

Actually, this assumption calls for empirical testing itself, along the lines drawn in Mizumoto’s original work. We leave it beyond the scope of our present paper, though, for further research.

In the literature the two effects are rarely distinguished and feature usually under the common heading of Epistemic Knobe Effect. Since this distinction is important to us, we restrict the use of the term Epistemic Knobe Effect to the scenarios with the word ‘knowledge’, and introduce the new term Doxastic Knobe Effect for the scenarios with the word ‘belief’.

Experiments 1a and 1b are devised by M&S’s to corroborate a general realist intuition and do not aim at discriminating distributive and non-distributive interpretation. The remaining experiments: 2a and 3 in our opinion fall short against their expected outcome. We will comment on this in Appendix 1.

Hypocrisy as a psychological phenomenon can be one of the underlying mechanisms of such behavior, and a pretty salient one (thus the name of the effect), although certainly, it is not the only possibility. There can be many legitimate reasons for which people support or advocate or act upon views not in line with their own personal preferences but rather as required by their institutional or legal commitments—just as it is assumed in the scenario presented in M&S’s study. We want to thank an anonymous referee for prompting us to explicitly acknowledge such possibilities.

Suppose a nationwide power company is operating coal-fueled powerplants. The company is aware that it is disastrous for the environment and regrets it; however, currently, they have no other options to provide power to all their clients. They may issue an official statement that they wholeheartedly support the green transformation and would be happy to rely on wind, sun and water only, but, alas, they find it currently impossible; and under the threat of switching the whole country off the power they find themselves forced, against their good will and honest preferences, to continue with the coal. Perhaps people would blame the company less for polluting the environment after publication of such official statement—if so, that would establish the GHE.

This was especially pronounced in the case of epistemic measures: the effect for belief may be classified as small, while for knowledge it falls within the conventional benchmark for a medium effect [see: Cohen (1988)]. Also, one should notice the differences between the sizes of the effects reported by M&S and those observed in our replication, for both the intentionality measure (original: d = 1.32 vs. replication: d = 0.73) and the moral assessment of the action (original: d = 1.59 vs. replication: d = 0.85). See footnote 9. for further discussion.

We are aware that effect size estimations based on a single study are rather imprecise (even in cases such as our Study 1, where the sample size was considerably large). Therefore, we do not want to claim that the real size of the Group Knobe Effect is smaller than what was originally reported by M&S. On the other hand, it is now a well-known fact that the effect sizes reported in empirical literature tend to be inflated. For example, a recent meta-analysis of the Epistemic Knobe Effect (Maćkiewicz et al., 2022) estimated its size as d = 0.70 [95% CI 0.62–0.78]; the Epistemic Group Knobe Effect observed in our study is therefore smaller than it might be expected. Nevertheless, we believe that even a small effect—if true—is theoretically interesting. We are grateful to an anonymous referee for encouraging us to elaborate on these issues.

During the period between data collection for our first and second study, a lot of doubts were raised about the quality of the data collected from Amazon MTurk. For that reason, we decided to use a more demanding attention task in our experiment. The content of the attention check can be found in Appendix 2.

One participant did not provide valid information about their age.

Subjects attributed more intentionality to individuals in the Harm condition (M = 5.41; SD = 2.52) than in the Help condition (M = 3.83; SD = 2.69).

Participants’ intentionality ratings were higher in the Support condition (M = 5.59; SD = 2.25) than in the Dissent condition (M = 3.72; SD = 2.82).

We were worried that this might not be a robust effect, therefore we ran an additional analysis using the bootstrapping method with M-estimators [see: Mangiafico (2015)]. The analysis employed 5000 bootstraps and confirmed the main effects for both factors, however, the interaction effect turned out to be non-robust.

Help: M = 5.61; SD = 2.06; Harm: M = 7.1; SD = 1.44.

Support: M = 6.58; SD = 1.65; Dissent: M = 6.19; SD = 2.14.

The numbers are summarized in Table 3 in Appendix 2.

When performing additional analyses on the original dataset (kindly provided by M&S), we noticed that there was an error in some figures reported for Experiment 2b: the crucial variables with Likert scales that ranged from 0 to 8 were, most likely mistakenly, recoded to variables ranging from 1 to 9 when M&S conducted their analysis (which means that the average ratings they report were raised by 1 compared to the actual figures). In Tables 2 and 3, we provide accurate figures that are calculated directly from the original dataset.

References

Alfano, M., Beebe, J. R., & Robinson, B. (2012). The centrality of belief and reflection in Knobe-effect cases: A unified account of the data. The Monist, 95(2), 264–289.

Beebe, J. R. (2013). A Knobe effect for belief ascriptions. Review of Philosophy and Psychology, 4(2), 235–258.

Beebe, J. R., & Buckwalter, W. (2010). The epistemic side-effect effect. Mind & Language, 25(4), 474–498.

Beebe, J. R., & Jensen, M. (2012). Surprising connections between Knowledge and intentional action: The robustness of the epistemic side-effect effect. Philosophical Psychology, 25, 689–715.

Block, N. (1980). Troubles with functionalism. Readings in Philosophy of Psychology, 1, 268–305.

Bratman, M. (1999). Faces of intention: Selected essays on intention and agency. Cambridge University Press.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Corlett, A. J. (2001). Collective moral responsibility. Journal of Social Philosophy, 32, 573–584.

Cova, F. (2015). The folk concept of intentional action: Empirical approaches. In W. Buckwalter & J. Sytsma (Eds.), Blackwell companion to experimental philosophy (pp. 121–142). Wiley-Blackwell.

Epstein, B. (2015). The ant trap: Rebuilding the foundations of the social sciences. Oxford University Press.

Feltz, A. (2007). The Knobe effect: A brief overview. The Journal of Mind and Behavior, 28(3/4), 265–277.

Gilbert, M. (1989). On social facts. Princeton University Press.

Goldman, A. (2002). Liaisons: Philosophy meets the cognitive and social sciences. MIT Press.

Hayek, F. A. (1942). Scientism and the study of society Part I. Economica, 35(9), 267–291.

Held, V. (1970). Can a random collection of individuals be responsible? Journal of Philosophy, 67, 471–481.

Hess, K. M. (2014). The free will of corporations (and other collectives). Philosophical Studies, 168(1), 241–260.

Hindriks, F. (2014). Normativity in action: How to explain the Knobe effect and its relatives. Mind & Language, 29(1), 51–72.

Huebner, B. (2013). Macrocognition: A theory of distributed minds and collective intentionality. Oxford University Press.

Knobe, J. (2003). Intentional action and side effects in ordinary language. Analysis, 63(3), 190–194.

Knobe, J. (2004). Intention, intentional action and moral considerations. Analysis, 64, 181–187.

Knobe, J. (2006). The concept of intentional action: A case study in the uses of folk psychology. Philosophical Studies, 130(2), 203–231.

Knobe, J. (2007). Reason explanation in folk psychology. Midwest Studies in Philosophy, 31, 90–106.

Knobe, J., & Mendlow, G. S. (2004). The good, the bad and the blameworthy: Understanding the role of evaluative reasoning in folk psychology. Journal of Theoretical and Philosophical Psychology, 24(2), 252.

List, C., & Pettit, P. (2011). Group agency: The possibility, design, and status of corporate agents. Oxford University Press.

Maćkiewicz, B., Kuś, K., Paprzycka-Hausman, K., & Zaręba, M. (2022). Epistemic side-effect effect: A meta-analysis. Episteme. https://doi.org/10.1017/epi.2022.21

Mangiafico, S. S. (2015). An R Companion for the Handbook of Biological Statistics. Retrieved 28 June, 2022, from https://rcompanion.org/rcompanion/

Michael, J. A., & Szigeti, A. (2019). “The Group Knobe Effect”: Evidence that people intuitively attribute agency and responsibility to groups. Philosophical Explorations, 22(1), 44–61.

Mizumoto, M. (2018). A simple linguistic approach to the Knobe effect, or the Knobe effect without any vignette. Philosophical Studies, 175(7), 1613–1630.

Paprzycka-Hausman, K. (2020). Knowledge of consequences: An explanation of the epistemic side-effect effect. Synthese, 197(12), 5457–5490.

Phelan, M., Arico, A., & Nichols, S. (2013). Thinking things and feeling things: On an alleged discontinuity in folk metaphysics of mind. Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences, 12, 703–725.

Popper, K. (1957). The poverty of historicism. Routledge.

Quinton, A. (1975). Social objects. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, 75, 1–27.

Searle, J. (1995). The construction of social reality. The Free Press.

Smiley, M. (2017). Collective responsibility. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), The Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy (Summer 2017). Routledge.

Strawson, P. (1974). Freedom and resentment. In P. Strawson (Ed.), Freedom and resentment (pp. 28–21). Methuen.

Strohmaier, D. (2020). Two theories of group agency. Philosophical Studies, 177(7), 1901–1918.

Sverdlik, S. (1987). Collective responsibility. Philosophical Studies, 51, 61–76.

Thomasson, A. L. (2019). The ontology of social groups. Synthese, 196(12), 4829–4845.

Tollefsen, D. (2002). Organizations as true believers. Journal of Social Philosophy, 33(3), 395–401.

Tollefsen, D. (2015). Groups as agents. Polity Press.

Tuomela, R. (2007). The philosophy of sociality: The shared point of view. Oxford University Press.

Tuomela, R. (2013). Social ontology. Oxford University Press.

Watkins, J. W. N. (1952). The principle of methodological individualism. The British Journal for the Philosophy of Science, 3, 186–189.