Abstract

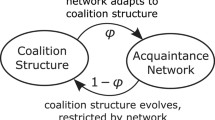

What I call "strategic injustice" involves a set of formal and informal regulatory rules and conventions that often lead to grossly unfair outcomes for a class of individuals despite their resistance. My goal in this paper is to provide the necessary conditions for such injustices and for eliminating their instances from our social practices. To do so, I follow Peter Vanderschraaf's analysis of circumstances of justice and expand his account by embedding "asymmetric conflictual coordination games" that summarize fair division problems in a dynamic social network. I use the network effect on such coordination games to explain the emergence of stable exploitative behavior and conventions by a class of individuals even in the presence of restraining efforts by others. I conclude that such unfair conventions are resilient to uncoordinated individual actions and interventions. In fact, maintaining a rough equality itself turns into another coordination problem. Finally, I show that something similar to a social movement that restructures the network of social relations is necessary to solve such coordination problems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Games in this reformulation represent strategic interactions among multiple actors where for every player the results are dependent on other players’ decisions as well as on their own. Players are simply the individuals that participate in the interaction, and strategies are the options available to them. A key feature of these games is that for each combination of strategies individuals choose, their payoffs determine the benefits or utility they enjoy.

This was originally introduced by Maynard Smith (1982).

Vanderschraaf (2018) explains these conditions in details and analysis their adequacy in chapter 3.

World in many agent-based models simply refer to the space in which agents exist.

To see the original form of this model, see Wilensky (1997). NetLogo Divide the Cake model. http://ccl.northwestern.edu/netlogo/models/DivideTheCake. Center for Connected Learning and Computer-Based Modeling, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL.

For a similar argument see, for example, Mills (2008) idea of a racialized society.

I will provide all three models upon request.

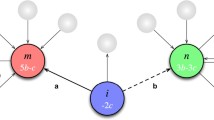

Myerson’s model was originally introduced as a reformulation of coalitional games. However, it does not require the common features of cooperative games.

The possible partitions are {{1,2}, {3}} or {{1}, {2,3}} or {{1,2,3}}.

Gordon-Bouvier (2020) introduce and discuss this idea in her book, Relational Vulnerability: Theory, Law and the Private Family.

For an example of cases in which individuals’ social networks affect their ability to survive or even access to justice institutions see Shami (2021).

None of the models that I have discussed so far in this paper distinguish “ties” or social interactions in terms of their strengths. But in network theory and its application to many real-world cases like finding jobs or dissemination of information the difference between contingent and infrequent interactions and robust relationships is a well-studied matter. For an example of a dynamic model of weak and strong ties in the context of labor marker see Zenou (2015). In fact, the models I provided can easily accommodate this distinction. But for the sake of simplicity, I did not elaborate this matter more. Thanks to the anonymous reviewer for pointing out this distinction and its importance in the literature.

References

Alexander, J. M. (2007). The structural evolution of morality. Cambrdige University Press.

Alexander, J. M., & Skyrms, B. (1999). Bargaining with neighbors: Is justice contagious? The Journal of Philosophy, 96, 588–598.

Ali, S. N., & Miller, D. A. (2016). Ostracism and forgiveness. American Economic Review, 106(8), 2329−2348.

Anderson, E. (2010). The imperative of integration. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Axelrod, R. (1984). The evolution of cooperation. Basic Books Inc, Publishers.

Axelrod, R., & Hamilton, W. D. (1981). The evolution of cooperation. Science, 211, 1390–1396.

Barry, B. (1989). Theories of justice. University of California Press.

Basu, K. (1986). One kind of power. Oxford Economic Papers, 38, 259–282.

Binmore, K. (1994). Game theory and the social contract: Just playing. MIT Press.

Binmore, K. (1998). The evolution of fairness norms. Rationality and Society, 10, 275–301.

Boserup, B., McKenney, M., & Elkbuli, A. (2020). Alarming trends in US domestic violence during the COVID-19 pandemic. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine, 38, 2753–2755.

Burt, R. S. (2002). The social capital of structural holes. The new economic sociology: Developments in an emerging field, 148(90), 122.

Diani, M. (2015). Social movements, civil repair, and social movement theory. Solidarity, Justice, and Incorporation: Thinking through The Civil Sphere, 96.

Diani, M., & Mische, A. (2015). Network approaches and social movements. In D. Della Porta & M. Diani (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of social movements. Oxford University Press.

Folbre, N. (2021). Gender inequality and bargaining in the U.S. labor market. Economic Policy Institute.

Foucault, M. (1977). Historia de la medicalización. Educación Médica y Salud, 11, 3–25.

Gauthier, D. (1986). Morals by agreement. Oxford University Press.

Gordon-Bouvier, E. (2020). Relational vulnerability. Palgrave Macmillan.

Hofbauer, J., & Sigmund, K. (1988). The theory of evolution and dynamical systems. Cambridge University Press.

Hume, D. (1777/1975). Enquiries concerning human understanding and concerning the principles of morals. In: L. A. Selby-Brigge. Clarendon Press.

Jackson, M. O., Rodriguez-Barraquer, T., & Tan, X. (2012). Social capital and social quilts: Network patterns of favor exchange. American Economic Review, 102(5), 1857–1897.

Jackson, M. O., & Rogers, B. W. (2007). Meeting strangers and friends of friends: How random are social networks? American Economic Review, 97, 890–915.

Lewis, D. (1969). Convention. Harvard University Press.

Mills, C. (2008). Racial liberalism. PMLA, 123, 1380–1397.

Mische, A. (2008). Introduction from Social Movement Studies Co-Editor.

Myerson, R. B. (1976). Graphs and cooperation in games. Mathematics of Operations Research, 2, 225–229.

Neumark, D. (2018). Experimental research on labor market discrimination. Journal of Economic Literature, 56, 799–866.

O'Connor, C. (2019). The origins of unfairness: Social categories and cultural evolution. Oxford University Press, USA.

Raub, W., & Weesie, J. (1990). Reputation and efficiency in social interactions: An example of network effects. American journal of sociology, 96(3), 626–654.

Rescorla, M. (2019). Convention. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), The Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy. The Metaphysics Research Lab.

Rosenfeld, R. A., & Kalleberg, A. L. (1991). Gender inequality in the labor market: a cross-national perspective. Acta Sociologica, 34(3), 207–225.

Rubin, H., & O’Connor, C. (2018). Discrimination and collaboration in science. Philosophy of Science, 31, 380–402.

Schauer, E. J., & Wheaton, E. M. (2006). Sex trafficking into the United States: A literature review. Criminal Justice Review, 31, 146–169.

Schelling, T. C. (1971). Dynamic models of segregation. Journal of Mathematical Sociology, 1, 143–186.

Shami, M. (2021). Access to justice in clientelist networks. The British Journal of Criminology, 62, 337–358.

Skyrms, B. (1994). Sex and justice. The Journal of Philosophy, 91, 305–320.

Skyrms, B. (1996). Evolution of the social contract. Cambridge University Press.

Skyrms, B. (2004). The stag hunt and the evolution of social structure. Cambridge University Press.

Skyrms, B. (2014). Evolution of the social contract. Cambridge University Press.

Skyrms, B., & Pemantle, R. (2000). A dynamic model of social network formation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 97, 9340–9346.

Smith, J. M. (1982). Evolution and the Theory of Games. Cambridge university press.

Sugden, R. (1986). The economics of rights, co-operation, and welfare. Palgrave Macmillan.

Sugden, R. (2004). The economics of rights. Palgrave Macmillan.

Vanderschraaf, P. (2018). Strategic justice: conventions and problems of balancing divergent interests. Oxford University Press.

Venkataramani, A., Daza, S., & Emanuel, E. (2020). Association of social mobility with the income-related longevity gap in the United States: a cross-sectional, county-level study. JAMA Internal Medicine, 180, 429–436.

Weibull, J. (1997). Evolutionary game theory. MIT Press.

Wilensky, U. (1997). StarLogoT.

Young, H. P. (1993). An evolutionary model of bargaining. Journal of Economic Theory, 59, 145–168.

Young, I. M. (1988). Five faces of oppression. Philosophical Forum, 19, 270.

Young, I. M. (2012). Responsibility for justice. Oxford University Press.

Zenou, Y. (2015). A dynamic model of weak and strong ties in the labor market. Journal of Labor Economics, 33, 891–932.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

T.C.: Strategic Justice, Conventions, and Game Theory Lead Guest Editor: John Thrasher, Michael Moehler.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Heydari Fard, S. Strategic injustice, dynamic network formation, and social movements. Synthese 200, 392 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-022-03576-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-022-03576-3