Abstract

This paper responds to arguments due to Joel Smith and Annalisa Coliva that try to show that James Pryor’s notion of wh-misidentification is philosophically uninteresting, and perhaps even spurious. It also proposes definitions of wh-misidentification and immunity to wh-misidentification which try to improve in various ways on the characterisations that standardly figure in the literature, and explores the relationship between misidentification and the epistemic structures characteristic of some kinds of Gettier cases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Certain judgments seem to be immune to error through misidentification when made on the right kinds of grounds. For example, suppose that I judge that I see a barn, as a piece of routine psychological self-knowledge. My judgment might be in error, since I may be looking at a convincing façade. But there doesn’t seem to be any room for me to be in error in the following way; I’m right that someone sees a barn, but I’ve misidentified them as myself. In contrast, if I judge that Lisa sees a barn, based on tracking her direction of gaze and so on, I can (in principle at least) fall into error either because Lisa is not seeing a barn or because it is not Lisa who is seeing a barn, but rather someone I’ve misidentified as Lisa.

In an influential paper (1999), James Pryor refined our understanding of this phenomenon in at least two respects. First, we can note that error through misidentification is a species of a more general phenomenon, which we can simply call misidentification.Footnote 1 Suppose that I judge that Lisa sees a barn, as above. In fact, it is not Lisa, but a lookalike. Now, here’s the twist (of a sort familiar from the literature on Gettier cases); as it happens, Lisa is seeing a barn right as I judge that she is. My judgment that Lisa sees a barn doesn’t involve an error through misidentification, since it’s correct. Still, it does involve misidentification, as I’m conceiving of it; my judgment is only true by luck, and this is because it rests on a mistaken identification.

Pryor also proposed that there are two varieties of misidentification to be reckoned with. I might be justified in judging that some particular person—the woman whose direction of gaze I’m tracking, say—sees a barn, and misidentify that woman as Lisa. Or I might have grounds for the existential claim that someone sees a barn, and misidentify Lisa as a witness to that existential. Let us call the first de re misidentification, and the second which object misidentification, or wh-misidentification for short. Corresponding to these, we will have two notions of immunity to misidentification: immunity to de re misidentification and immunity to wh-misidentification. Having distinguished these, Pryor argues that immunity to wh-misidentification is the more interesting and fundamental notion. He bases this latter conclusion largely on the contention that it’s immunity to wh-misidentification that we need to appeal to if we’re to accommodate Sydney Shoemaker’s (1970) observation that the metaphysical possibility that one might have memory impressions that derive from someone else’s past shows (contrary to Evans 1982), that memory-based judgments about one’s own past are vulnerable to misidentification.

I have two main aims in this paper. First, I respond to two attempts to show that Pryor’s distinction between de re and wh-misidentification is not as deep or as significant as he suggests, due to Joel Smith and Annalisa Coliva. In Sect. 2 I offer preliminary characterisations of de re misidentification, wh-misidentification, and the respective varieties of immunity more carefully, and then in Sects. 3 and 4 I lay out and criticise Smith’s and Coliva’s arguments against wh-misidentification respectively. My second aim in this paper is to improve our understanding of wh-misidentification and the associated notions of immunity and vulnerability, and I do this by offering refined characterisations in Sect. 5, in light of morals drawn from earlier sections. My account centres and explores a connection that emerges between the phenomenon of misidentification and the kinds of epistemological structures characteristic of some familiar Gettier cases.

2 Two varieties of misidentification

Let’s begin by sharpening our understanding of Pryor’s two varieties of misidentification. Loosely following Pryor (1999: 274–275), let us characterise a case of de re misidentification as follows:

-

i.

One has grounds G that justify one in judging, of some particular object b, that it is F.

-

ii.

One mistakenly (though perhaps justifiably) accepts that a = b.

-

iii.

One judges that a is F, and this judgment rests on one’s belief that b is F together with one’s acceptance of the mistaken bridging identity claim.Footnote 2

In our earlier example, I have grounds that justify me in judging that the woman I am observing sees a barn. However, I mistakenly believe that this woman is Lisa, and on that basis I judge that Lisa sees a barn. In line with a point made in the introduction, this is not intended as a characterisation of error through misidentification. Nothing in the conditions just offered requires that one’s judgment that a is F be false; rather, given the misidentification, one’s judgment can at best be true by luck. Let us say that a judgment is immune to de re misidentification when made on certain grounds when it’s impossible for cases of de re misidentification to arise when that judgment is made on those grounds.Footnote 3

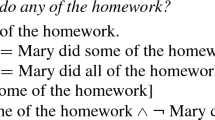

The basic idea underlying Pryor’s characterisation of immunity to wh-misidentification is simple enough: a judgment a is F is immune when made on certain grounds just in case it’s impossible for that de re judgment to be defeated and yet one’s grounds continue to justify one in the fallback existential claim that something is F.Footnote 4 However, Pryor’s own attempt to make this more precise is surprisingly complex and involves appeal to notions not needed to state his account of immunity to de re misidentification. Here, first of all, are his conditions for wh-misidentification:

i′. One has grounds G that offer one knowledge of the existential generalization that something is F.Footnote 5

ii′. Partly on the basis of G, the subject is also justified, or takes herself to be justified, in believing of some object a that it is F.

iii′. But in fact a is not F. Some distinct object (or objects) y is F, and it’s because the grounds G “derive” in the right way from this fact about y that they offer the subject knowledge of the existential. (1999: 282).

Here’s Pryor’s own example to illustrate (1999: 281):

I smell a skunky odor, and see several animals rummaging around in my garden. None of them has the characteristic white stripes of a skunk, but I believe that some skunks lack these stripes. Approaching closer and sniffing, I form a belief, of the smallest of these animals, that it is a skunk in my garden. This belief is mistaken. There are several skunks in my garden, but none of them is the small animal I see.

In this example, I have grounds that offer me knowledge of the existential claim that there’s a skunk in my garden, namely the skunky odour (and perhaps my visual evidence of the presence of animals in my garden). Partly on the basis of the odour again, I gain (or take myself to gain) justification that the smallest of the animals in my garden is a skunk. However, my grounds do not derive from this animal, but from other animals in my garden. Pryor stipulates that my judgment that this animal is a skunk in my garden is mistaken, but in principle it could instead be true by luck; we can suppose, for example, that I’m right that some skunks in fact lack stripes, and that the smallest animal in my garden is a case in point, but that it has not contributed to the skunky odour in my garden.Footnote 6 Were I to somehow learn that the animal I form my judgment about is not in fact responsible for the odour I can smell, this would defeat my judgment that that (namely, the smallest animal in my garden) is a skunk in my garden, yet the existential judgment that there is a skunk in my garden would remain justified by my grounds.

How are these two varieties of misidentification related? The skunk example is meant to illustrate that cases of wh-misidentification need not be cases of de re misidentification (1999: 285), and this is an issue we’ll return to in more detail below. Pryor also holds that cases of de re misidentification need not be cases of wh-misidentification. In Pryor’s example, I see that the blue-coated man is carrying a gun, and having misidentified this man as Sam, I form the false belief that Sam is carrying a gun (1999: 275). This is a case of de re misidentification, but Pryor says it’s not a case of wh-misidentification since ‘I do correctly come to know, of the blue-coated man, that he is carrying a gun’ (1999: 285). However, things get more interesting at the level of immunity and vulnerability to different varieties of misidentification. Pryor argues that if a judgment is immune to wh-misidentification when made on grounds G, then it will also be immune to de re misidentification relative to G. Here’s the thought. Suppose I judge that a is F on grounds G, and it’s not ruled out that this judgment rests on a mistaken judgment that a is identical to b together with an antecedent judgment that b is F. Then it’s possible that one’s grounds G offer one knowledge that something is F because they derive from b, and one justifiably but mistakenly take them to derive from a. In contrast, a judgment’s being immune to de re misidentification doesn’t entail that it’s immune to wh-misidentification; for example, Pryor’s takes the skunk example to be a case of (vulnerability to) wh-misidentification in which one’s judgment is immune to de re misidentification, since

my belief that that animal is a skunk does not rest on any identity assumption. There is no particular animal I antecedently know to be a skunk, which I could reidentify as the small animal I see. (1999: 285–286)

It’s these claims—that cases of wh-misidentification don’t involve mistaken identities of the sort characteristic of de re misidentification, and that immunity to de re misidentification doesn’t entail immunity to wh-misidentification—that give rise to most of the controversy surrounding immunity to wh-misidentification and Pryor’s discussion of it. The first controversy concerns Pryor’s claim that cases such as the skunk example feature judgments that don’t rest on any identity assumptions, and the second concerns the way he exploits the apparent gap between immunity to de re misidentification and immunity to wh-misidentification in offering a resolution to the debate between Shoemaker and Evans outlined in the introduction. What I have to say in this paper will engage directly with the first of these controversies, but while I’ll touch on the second controversy in the conclusion, I will have to leave those issues for another occasion.

3 Smith’s objection

I’ll start in this section and the next by examining the two attempts to show that wh-misidentification lacks the significance that Pryor accords it, and that we should be focused on de re misidentification. Smith’s argument starts from the premise that we want to preserve the close relationship between self-ascriptions that display immunity to misidentification and those that are manifestations of self-consciousness. So an account of immunity to misidentification should entail that ‘self-ascriptions that are agreed by all to be central to our conception of ourselves as self-conscious subjects’, paradigmatically self-ascriptions of occurrent mental states, are immune (2006: 274).

Smith then argues that many such self-ascriptions are not immune to wh-misidentification, and so that this can’t be the right way of understanding immunity to misidentification if we want to preserve the tie to self-consciousness. Consider again my judgment that I see a barn, and suppose that I receive the following defeating evidence; I am reliably told that my visual impression of a barn is caused by someone else currently seeing a barn. This overriding evidence defeats my judgment, but leaves me justified in retreating to the fallback existential claim that someone sees a barn (Smith 2006: 278). The point generalises well beyond this particular case, since it looks like we’ll typically be able to concoct such defeating evidence, even when we’re dealing with self-ascriptions of occurrent mental states on the basis of introspection.

The obvious problem with this objection is that the reason that one’s original grounds together with the defeating evidence justify the fallback existential claim isn’t that one’s original grounds were structured in such a way that an existential-supporting portion is left untouched by the defeater. Rather, it’s that the defeater itself furnishes one with the existential information that someone sees a barn. Smith recognises this problem, writing (2006: 279–280):

Can’t we simply reformulate our definition of [immunity to wh-misidentification] so that the justification that the subject has for retreating to the general proposition must already be there in the justification for the original singular judgment?

If our characterisation of immunity to wh-misidentification permits the defeating evidence to provide one’s justification for the fallback existential, then whether one’s original evidence in a given case would be capable of supporting that existential claim becomes irrelevant to whether the characterisation is met. So the proposal Smith floats here looks well motivated; we should require that one’s original evidence, and not merely one’s defeating evidence, can justify the fallback existential in the face of evidence that defeats one’s de re judgment.

However, Smith argues that if we impose this requirement, then we’ll collapse wh-misidentification into de re misidentification. His argument is contained entirely in the following sentence:

If, in the justification that I have for the singular judgment ‘I am F’ I am able to discern two elements, one of which can be discarded and the other retained, leaving me justified in thinking ‘Someone is F’, then it looks very much as if that original judgment was based on the information that a was F and that I = a, i.e. it was based on an identification. (2006: 280)

It’s worth noting, first of all, that there isn’t much of an argument here. Rather, the characteristic epistemic architecture of de re misidentification is introduced without any consideration of alternatives. More importantly, there are principled reasons to resist Smith’s attempt to saddle his opponents with that architecture in examples like Pryor’s skunk. My justification for the existential claim that there is a skunk in my garden comes from the skunky odour, and so plausibly does not derive from any justification I may have for judging that some particular object is a skunk in my garden. As Pryor writes (1999: 282, italics in original):

I’m not yet in a position to believe, of some thing that I’m smelling, that it is identical to anything else. In fact, I’m not yet in a position to hold any de re beliefs about any of the things I’m smelling. I don’t yet have any correct beliefs, about some particular animal, that I am smelling it, or that it is a skunk in my garden. My problem is precisely to arrive at such a de re belief.Footnote 7

The problem for Smith is that he commits to all putative examples of wh-misidentification having the same underlying structure; there’s a parent judgment, a is F, and a (mistaken) identification, b = a. And Pryor’s point in the passage just quoted is that one isn’t in a position to form any parent judgment of this form in the example described.

Moreover, Pryor offers a proposal about the kinds of grounds one has in cases of wh-misidentification that invalidates Smith’s argument in the sentence quoted above. Pryor’s focus is memory, and according to his proposal, memory offers one a ‘package deal’ of justification (1999: 296); ‘it tells me that someone performed a certain action, and it also tells me that I am the person who performed that action’. Now, recall Smith’s argument; he suggested that if I can discern two ‘elements’ in my original grounds for the singular judgment that I am F, one of which can be defeated while the other continues to justify the fallback existential, then it looks like my judgment must rest on the de re judgment that a is F and the identity claim that I am a. This doesn’t follow, if my grounds offer me the kind of ‘package deal’ that Pryor suggests. The two ‘elements’ will just be the two components of the package that Pryor describes, neither of which is as Smith claims it must be.

Smith has shown neither that immunity to wh-misidentification fails to apply to even promising cases, nor that wh-misidentification collapses into de re misidentification; for all he has shown, it remains distinct and philosophically significant.Footnote 8

4 Coliva’s Objection

Annalisa Coliva (2006) offers an argument for the conclusion that wh-identification is not merely philosophically insignificant, but in fact ‘spurious’. Consider Pryor’s skunk example again. I start out with independent warrant for judging that there is a skunk in my garden, and I go wrong in misidentifying the animal I can see as the witness to that existential; I go wrong in judging that this animal (that I can now see) is a skunk. But, Coliva asks, what are the grounds of this final judgment? Coliva’s proposal is that I make this judgment because I accept a false identity claim, namely that this animal (that I can currently see) = the animal which is actually responsible for this odour I can smell (Coliva 2006: 412). It’s the fact that I believe this, together with my recognition of the odour as that characteristic of a skunk, that explains why I (mistakenly) judge that this animal is a skunk. Moreover, just as in paradigm cases of de re misidentification, this error is due to my having judged on the basis of a false identity claim. We can lay Coliva’s reconstruction out as follows, and this will give us a format for representing and comparing different proposals about different examples:

- Existential claim:

-

There is a skunk in my garden

- Parent judgment:

-

The animal which is actually responsible for this odour I can smell is a skunk in my garden

- Identity component:

-

This animal (that I can now see) = the animal which is actually responsible for this odour I can smell

- Final judgment:

-

This animal is a skunk in my garden

Any further differences between paradigm cases of wh-misidentification and paradigm cases of de re misidentification are, Coliva contends, merely superficial, to do with the range of concepts that figure in the mistaken identity claims. In this sense, Coliva takes Pryor to have failed to uncover a genuinely epistemically distinct variety of misidentification.

None of the points I made above in response to Smith seem to get purchase here. Coliva offers a prima facie plausible account of the grounds underwriting cases of wh-misidentification, and she illustrates it with Pryor’s own skunk example (or so it appears at first glance). And Coliva doesn’t say anything to beg the question against Pryor’s ‘package deal’ proposal concerning the justifications that figure in cases of wh-misidentification. However, Coliva’s argument for the spuriousness of wh-misidentification faces problems of its own.

First, Crispin Wright has constructed other examples of wh-misidentification that seem to cause Coliva’s proposal to misfire. Consider the following:

I am lost in a sandy desert and, attempting to walk out, come across footprints which I misidentify as my own, concluding somewhat desperately, “I am going round in circles.” Here the footprints give me reason to think that someone (maybe with feet about my size) has passed this way already; and I then misidentify—mistake myself for—the witness of that true existential claim. (2012: 256)

Taking Coliva’s treatment of the skunk example as our model, we want to determine the grounds of my judgment that I have passed this way already. In the skunk case, my grounds for my mistaken judgment that this animal that I can now see is a skunk featured the parent belief that the animal in my garden that is actually responsible for this odour I can smell is a skunk, together with the mistaken identify claim that this animal that I can now see = the animal in my garden that is actually responsible for this odour I can smell; it is, of course, the presence of the latter—the mistaken identification—that allows Coliva to suggest that wh-misidentification doesn’t differ in epistemically significant respects from de re misidentification. Returning to the sandy desert, Wright thinks that it seems clear what the mistaken identity claim should be, according to Coliva; it should be that I = the person who has passed this way before. But what’s the parent judgment in this example? Following Coliva’s recipe, Wright claims, commits us to holding that it is this: the person who caused these footprints in the sand has passed this way already. However, this seems too informationally impoverished—Wright calls it ‘near enough, a tautology’ and ‘something quasi-tautologous’ (2012: 258)—to figure as part of a plausible reconstruction of my grounds in the example.Footnote 9 All that there is to go on in the parent judgment is that the person did the thing that caused the subject’s grounds. In this respect, Wright’s case differs from Pryor’s skunk example, where the object that I misidentify as the witness of the existential is one I can think of independently of its being the cause of my grounds (since I can think of it as the smallest of the animals I can see rummaging around my garden).

I think that Wright’s example poses a genuine problem for Coliva’s proposal, but his objection stands in need of clarification, refinement, and defence. I have three points to make here. The first is just a matter of clearing up Wright’s formulation of his objection. The reconstruction of the subject’s grounds in the desert example that Wright offers on Coliva’s behalf seems to get things rather back to front. In essentials, his reconstruction is as follows:

- Existential claim:

-

Someone has passed this way already

- Parent judgment:

-

The person who caused these footprints in the sand has passed this way already

- Identity component:

-

I = the person who has passed this way before

- Final judgment:

-

I am the person who caused these footprints (and so I’m going around in circles)

However, I offer the following as in the same spirit but more plausible:

- Existential claim:

-

Someone has passed this way already

- Parent judgment:

-

The person who caused these footprints in the sand has passed this way already

- Identity:

-

I = the person who caused these footprints

- Final judgment:

-

I have passed this way already (and so I’m going around in circles)

The idea is that the footprints give me grounds to believe the existential claim. Moreover, the fact that there’s not likely to be another person leaving footprints in the desert together with these footprints matching my own in size justifies me in (mis)identifying the footprints as my own. This, together with the parent judgment, leads me to conclude that I have passed this way already, thereby misidentifying myself as witness to the existential claim. Since the parent judgment is the same in both versions, Wright’s objection is unaffected by the proposed change.Footnote 10

My second point does require us to rethink Wright’s objection more substantially. Coliva has recently responded to his objection, suggesting that there’s an alternative and more plausible way to reconstruct the subject’s grounds in Wright’s example than the one he offers on her behalf:

‘…someone sees footprints in the sand going around and forms the mistaken judgement ‘I am going around in circles’. Here, again it is quite easy to see how the judgement could be taken to be based on the mistaken identification component ‘I = the person who is responsible for these footprints I am seeing’ (and since these footprints go around in circles, I then infer that I am going around in circles). Now, Wright’s objection is that the identification component would be nearly tautological. This depends on Wright’s reconstruction, according to which we should start off with ‘The person responsible for these footprints going around in circles is going around in circles’. But this is a straw man.Footnote 11 As we saw, the person sees footprints, she realizes those footprints go around in circles. She takes herself to be identical to the person who has made those footprints, from which she infers she is going around in circles. Clearly, when correctly represented, in neither case is the identification component (nearly) a tautology: it is not part of the meaning of ‘that animal’ or ‘I’ that it be the animal responsible for the odor I can smell, or that it be the person who is causally responsible for certain footprints. Yet, I would suggest that precisely because those identification components are readily available to us, based on the information we contextually have (e.g. a certain odor or certain footprints, etc.), we do not have any reason to follow Pryor in suggesting that these cases do not involve any identification component.’ (Coliva 2018: 782)

We can lay Coliva’s proposal in this passage out as we did with the proposal Wright suggested on her behalf. Unfortunately, Coliva isn’t explicit about what she takes the relevant existential claim to be. We might carry over what Wright suggested on her behalf, namely ‘someone has passed this way already’. However, looking at the quote above suggests an alternative, since the final judgment seems to be ‘I am going around in circles’ rather than ‘I have passed this way already’. Hence we have:

- Parent judgment:

-

These footprints go around in circles

- Existential claim:

-

Someone is going around in circles

- Identity:

-

I = the person who caused these footprints

- Final judgment:

-

I am going around in circles

This time we start with the parent judgment, made on the basis of seeing the footprints, and recognising that it’s unlikely that there are two walkers out in the desert. This then plays a role in justifying both the existential claim and, via the identity, the final judgment which misidentifies myself as the witness to that existential.

However, I don’t think Coliva’s proposal here is a natural or independently plausible reconstruction of my grounds or reasoning in the example. The natural progression of the reasoning in the example is, I contend, as follows: the reason that I come to mistakenly think that the footprints go in a circle is that I have misidentified those footprints as my own, due to the match in size and the unlikeness of their being a second person wandering around leaving such footprints. On that basis I infer that I am going in circles; after all, if I were not going in circles I wouldn’t have re-encountered my own tracks. Coliva’s proposal conflicts with this reconstruction of the reasoning involved in this case. Her alternative suggestion is that upon seeing the footprints, I infer that they’re going around in circles (based, as noted above, on the unlikeliness of two walkers being out in the desert), and only then start to draw inferences about whose footprints they might be, via the false identification of myself and the maker of the footprints. This seems relatively unnatural and unmotivated. Again, insisting that the example involves a subject who reasons from a mistaken identification leads us to distort our picture of the grounds and reasoning involved, in ways that lack independent motivation.Footnote 12

That’s not a knockdown objection to Coliva’s proposal, but it can be further supported by considering a rival positive proposal about the subject’s grounds and reasoning in Wright’s example, one that elaborates on the intuitive account sketched in the previous paragraph. This will be my third point of advance on Wright’s own discussion, since he isn’t very explicit on this issue. Based on the footprints, the subject has grounds for:

- Existential claim:

-

Someone has passed this way already

This existential claim, together with the improbability that someone else is walking around this desert (with footprints roughly matching the size and shape of my own), justify me in believing that:

- Parent judgment:

-

These are my footprints

So:

- Final judgement:

-

I have passed this way already (and so I’m going around in circles!)

The identification of myself as witness to the existential doesn’t involve a misidentification, but rather an inference to the best—in this case, to what’s seemingly the only plausible—explanation; I first see the footprints and infer that they must be mine. This then serves as the parent judgment for the obvious further conclusion that I have passed this way around (and so must be going in circles). The inference here resembles the one made by John Perry’s infamous shopper, who concludes that he is making a mess based on this being the best explanation of why he can’t catch up with the person whose sugar sack is leaking (Perry 1979). Indeed, Wright’s example is essentially a variant of Perry’s, changed so that the subject’s final judgment is an error through misidentification rather than a truth.Footnote 13

On the analysis I have offered, Wright’s example is a genuine case of wh-misidentification, one in which the inferential step involved doesn’t rest on any mistaken identity claim. If one accepts my claim that this analysis of the example is more natural and better motivated by features of the case than the alternative offered by Coliva, that undermines her argument for maintaining that all cases of wh-misidentification are merely superficial variants of de re misidentification. It shows that it’s only by insisting on a distorted and unmotivated account of the grounds involved in examples like Wright’s over a more natural alternative that it can be made to seem plausible that wh-misidentification is ‘spurious’, only differing from de re misidentification in superficial respects. This isn’t quite what Wright’s objection claimed to show; Wright concluded that there are examples of wh-misidentification that could only be treated along the lines suggested by Coliva by rendering the subject’s grounds completely informationally impoverished. I haven’t vindicated this conclusion, but I’ve tried to show that Wright’s example is genuinely problematic for Coliva’s argument, and that her recent response doesn’t suffice to see the problem off. None of this should be taken as a denial that there are deep similarities between de re and wh-misidentification—I’ll try to draw these out below in Sect. 5—but contrary to Coliva’s conclusion, they are distinct phenomena.

There’s a second objection to Coliva, one that Wright seems not to have been in a position to appreciate (though others have: see in particular Garcia-Carpintero 2018: 3320). As Wright characterises wh-misidentification, it occurs when ‘a thinker goes into a situation equipped with grounds for a unique existential claim—a claim that there is exactly one object meeting a certain condition—and then, on receipt of additional (mis)information of a certain kind, proceeds to misidentify a particular object as the witness of that claim’ (2012: 255, emphasis in original). However, the insistence that the subject in cases of wh-misidentification has grounds that support a unique existential claim doesn’t seem to have any basis in Pryor’s original discussion, and his skunk example doesn’t fit this description:

I smell a skunky odor, and see several animals rummaging around in my garden. None of them has the characteristic white stripes of a skunk, but I believe that some skunks lack these stripes. Approaching closer and sniffing, I form a belief, of the smallest of these animals, that it is a skunk in my garden. This belief is mistaken. There are several skunks in my garden, but none of them is the small animal I see. (Pryor 1999: 281, emphasis added)

The skunky smell and rummaging animals in no way give me grounds to think that there is at most one skunk in my garden, and the resulting mistaken belief that I form reflects this; Pryor is clear that my mistaken belief is that the smallest of the animals that I can now see is a skunk in my garden.

What’s the bearing of these observations on Coliva’s argument against wh-misidentification? It’s this; at a crucial juncture in her argument, she too assumes that I am licensed to take there to be only one animal that’s responsible for the skunky odour that I can smell. Her proposal, recall, is that I mistakenly believe that the animal that I can now see is a skunk because I have based this belief on the parent judgment that the animal in my garden which is actually responsible for this odour I can smell is a skunk and the following identity claim: this animal (that I can now see) = the animal in my garden which is actually responsible for this odour I can smell. However, we’ve just seen that in Pryor’s example, I lack any justification for thinking that at most one of the animals that I can see in my garden is responsible for the skunky odour that I can smell. So my grounds for my mistaken belief that the smallest animal that I can see is a skunk don’t plausibly include either of the premises that Coliva insists they include, since both premises presuppose that there’s a unique animal in my garden which is actually responsible for this odour I can smell, and to repeat, I have no justification for that at all.

In the end Coliva’s proposal about the kinds of grounds involved in wh-misidentification meets the same fate as Smith’s; it turns out that it isn’t even plausible for the primary example that Pryor offers us to illustrate the phenomenon.Footnote 14 Hence Coliva’s proposal about the kinds of grounds involved in apparent cases of wh-misidentification is to be rejected, and her argument that wh-misidentification is spurious can be resisted.

5 What is immunity to wh-misidentification?

So far I have argued that neither of the attempts in the literature to show that wh-misidentification lacks significance or collapses into de re misidentification are successful. Let us turn now to the task of offering characterisations of wh-misidentification and the associated notions of immunity and vulnerability. I take as my starting point the idea that our characterisations should be modelled as closely on our characterisations of de re misidentification and immunity to de re misidentification as possible, in order to be able to see both the similarities and the differences. Here is my proposed account of cases of wh-misidentification:

-

i″. One has grounds G that justify one in believing the existential generalization that something is F.

-

ii″. One’s grounds G do not justify one in believing that everything (in the relevant domain) is F.

-

iii″. Partly on the basis of G, one has justification (or believes oneself to have justification) for believing of some particular object a that it is F.

-

iv″. However, one’s grounds G do not derive from the fact that a is F, if this even is a fact.Footnote 15

Consider Pryor’s skunk example once again. On the basis of the skunky odour in my garden, I have grounds G that justify me in believing the existential generalisation that there is a skunk in my garden (but not the corresponding universal generalisation). Partly on the basis of the smell, and partly on the basis of vision, I gain justification for believing that the smallest of the animals I can see running around is a skunk in my garden. However, my grounds G do not derive from the fact that the smallest of the animals in my garden is a skunk; indeed, in the case as Pryor describes it, the animal in question isn’t even a skunk. According to clause iv″. that’s not essential to wh-misidentification; as I emphasised above the crucial point is that even if it had been a skunk, the truth of my belief would be a matter of luck, given that my grounds don’t derive from this fact about that animal.Footnote 16

Clause ii″. wouldn’t be necessary if clause i″. had required that one’s grounds justify one in believing a unique existential claim—something I rejected in the previous section. With clause i″. as it stands, clause ii″. is needed to exclude certain kinds of false positives. For example, suppose that one’s grounds justify one in believing that something is F, and that if something is F then everything is. For example, I might know that someone has a maximally infectious disease, and know that if one person has it, the whole group must have it too. Since Steve is one of the group, I conclude that Steve has the disease. Without condition ii″., this would meet the conditions for wh-misidentification, but intuitively it’s not a case of wh-misidentification; indeed, this reasoning to the conclusion that Steve has the disease seems unimpeachable.Footnote 17

Given this account of wh-misidentification, we can then characterise immunity and vulnerability to wh-misidentification straightforwardly, and in a way that parallels Pryor’s own characterisation of immunity and vulnerability to de re misidentification: a judgment that a is F is immune to wh-misidentification when justified by grounds G just in case it is not possible for one to make that judgment on grounds G, and that judgment exhibit wh-misidentification, and it is vulnerable to wh-misidentification just in case it’s not immune.Footnote 18

These characterisations of wh-misidentification and immunity to wh-misidentification are simpler and more natural than Pryor’s own, and they are modelled as directly as possible on the characterisations of de re misidentification and the associated notion of immunity that Pryor himself proposes. This may not be immediately apparent, just from looking at both sets of clauses. So what are the key differences with Pryor’s own account, and why do they mark improvements?Footnote 19 Pryor’s clause ii′ and my clause iii″ are virtually identical, so we can bracket those. Pryor doesn’t include any analogue of clause ii″, though the motivations for including some such clause, rehearsed above, seem just as pressing. The really important differences concern my clauses i″ and iv″. Clause i″. requires only that one’s grounds justify the existential generalisation, while Pryor’s clause i′. requires that one’s grounds offer one knowledge of that existential generalisation. As noted above, ‘offering one knowledge’ is a strangely defined technical notion for Pryor, and it’s also factive, which means that this clause leads to issues with accommodating cases of wh-misidentification in which the existential claim in question is justified but false; I’ll give an example shortly. The same point motivates the differences between Pryor’s clause iii′. and my iv″. Pryor’s clause requires that some other object (other than the one that the subject misidentifies as a witness) is F and is responsible for the grounds the subject has, and so that the existential generalisation that something is F be true. Pryor’s clause iii′. also requires that it is false that the object identified by the subject is F, despite his recognition elsewhere in his paper that such an error doesn’t seem to be crucial to misidentification. These differences are all respects in which my account of wh-misidentification preserves similarities with de re misidentification better than Pryor’s own; according to Pryor’s own account, laid out in Sect. 2 above, cases of de re misidentification do not require that one’s final judgment that object b is F is false, nor that one’s original judgment that a is F is true, but only that one judges that b is F because of a false identification of a and b. The differences introduced by Pryor obscure some of the structural similarities between de re misidentification and wh-misidentication, and there’s no obvious rationale for them.Footnote 20 That’s why I claim that my account of wh-misidentification (and the associated notion of immunity) is simpler than Pryor’s.

However, it should be conceded that the apparent simplicity of my account may be superficial. The idea it’s trying to capture is hopefully clear enough. One has general grounds for an existential which also (perhaps in collaboration with some other information) justify one in identifying an object as witness, but contrary to appearances, one’s grounds aren’t really caused or explained by that object having the property in question. As a result, given one’s grounds, one’s judgment that this object is a witness ends up false or merely true by luck. The account attempts to make this kind of epistemic structure clearer—but with appeal to some rather vague and slippery notions, such as the requirement that one’s grounds for the existential not ‘derive’ from particular facts about the particular object which one (mis)identifies as a witness.

This is a reasonable worry to have with the account I’ve proposed. I have several things to say in response. First, notice that many of these issues are ones that I have inherited from Pryor’s own account, since my clauses are modelled on his. In particular, the issues raised in the previous paragraph will equally bite for Pryor. That doesn’t mean we should ignore these issues, but it does suggest that they are general, rather than specific to my proposal.

Second, these worries should not at all come as a surprise, given the nature of the account offered here. The account in a sense centres the point I started with, namely Pryor’s suggestion that error through misidentification isn’t a particularly significant category. Instead, the key thing about misidentification is that it gives rise to justificatory structures which can equally lead to to false beliefs or to Gettiered ones, depending on how the facts are. As an analogy, consider one of Gettier’s own examples (1963). Smith justifiably believes that the person who will get the job has 10 coins in their pocket, based on having counted the coins in Jones’s pocket and having authoritatively (but misleadingly) heard that Jones will get the job. Whether this belief is false or Gettiered depends on how things happen to stand with respect to the number of coins in Smith’s own pocket; the underlying fact is that Smith’s grounds don’t derive from the number of coins in his own pocket, and that’s why his belief can at best be true by luck. On the account offered here, misidentification involves grounds that give rise to ignorance in this Gettier-like manner. Given this, it’s no wonder that it runs into many of the problems that go under the banner of ‘the Gettier problem’ in contemporary epistemology: that is, the problem of offering an informative and non-circular account of the distinction between knowledge and ignorance in terms of true belief, in light of Gettier’s counterexamples to the tripartite account.Footnote 21

Third, the comparison to Gettier cases may suggest there will be limits to how much I can say in elaborating the account offered, but it also sheds some light on how to understand the account. The idea underlying the conditions for wh-misidentification I have offered is that in cases that meet these conditions, as in Gettier cases such as the one described above, there’s a disconnect between what justifies a particular belief and the facts that cause or explain its truth (or falsity). In Gettier’s example, Smith’s belief that the person who will get the job has ten coins in his pocket is justified via the false but justified belief that Jones will get the job and the true belief that Jones has ten coins in his pocket, when what makes Smith’s final belief true are facts about his own employment situation and the number of coins in his own pocket. It’s this disconnect that’s responsible for the fact mentioned above, namely that Smith’s belief can at best be true by luck.Footnote 22 Pryor’s skunk case has essentially this dynamic too, though the details are a little different and more complicated than in Gettier’s example.Footnote 23 I have grounds that justify me in believing the existential claim that there’s a skunk in my garden. These grounds derive from a particular animal (or particular animals), namely the animal(s) responsible for the skunky odour. I mistakenly infer that that—the smallest of the animals I can see in my garden—is responsible for the smell, and so erroneously conclude that it is a skunk in my garden. If we can make sense of the disconnect characteristic of Gettier cases, we should be able to make sense of the structure imposed on cases of wh-misidentification by clause iii″, even if we’d like to be able to say something more informative about both.

Since this has been a big part of the motivation behind my approach in this section, I also want to stress again the commonalities between de re misidentification and wh-misidentification on the account offered here. As noted above, de re misidentification also has a Gettierish structure. One’s final judgment that a is F can at best be true by luck, since the link with b’s being F is spurious (even though one was justified in taking a = b to be true); in cases of error through misidentification, one’s judgment is false because a doesn’t just happen to match b in the relevant respect.Footnote 24

Could we do better? I’ll close this section by considering a recent rival account of immunity to wh-misidentification, due to Daniel Morgan, that promises to avoid the challenges faced by my account altogether.Footnote 25 I’ll argue that it just saddles us with yet more difficult problems.

Morgan’s account has two principal parts. First, we have a definition of immunity to wh-misidentification which appeals to the notion of ‘independent knowledge’:

A judgment of the form ‘a is F’ is, relative to certain grounds g, immune to error through wh-misidentification if and only if g justifies ‘a is F’ without offering independent knowledge of ‘Something is F’. (2019: 446)

Second, we have a criterion for when grounds offer independent knowledge, in the relevant sense:

Grounds g offer knowledge of q that is independent of the justification they provide for p if and only if one can know that q on the basis of g, even if p is false. (2019: 447)

We can illustrate this account by taking a final pass at Pryor’s skunk example. My judgment that this (the smallest animal I can see in my garden) is a skunk is vulnerable to wh-misidentification given my grounds since those grounds justify this judgment, and even if this judgment is false, my grounds can afford me knowledge that something in my garden is a skunk (given the skunky odour). This shows that my grounds justify my judgment that this is a skunk while offering me independent knowledge of the existential. We can see that it must be independent knowledge because I’d still have it even if my judgment about this particular animal were false, and you can’t get knowledge from falsehood; that is, inferential knowledge can only come from premises which are themselves true (2019: 447).Footnote 26

So far so good, and Morgan seems to have bypassed the need to try to elucidate the tricky notions that appear in both Pryor’s characterisation and my own. However, there are at least two reasons to be worried with this alternative. First, the appeal to the factive concept, knowledge, in the characterisation leads to some intuitively odd results.Footnote 27 Suppose that there’s a skunky odour in my garden, but no skunks; the odour is due to tires being burned in the neighbourhood. Suppose also that these (misleading) olfactory grounds, together with my visual impression of the animals in my garden, justifies me in believing of that (the smallest of those animals) that it is a skunk. So the example is exactly as in Pryor’s original, except that the existential claim that there’s a skunk in my garden happens to be false. I don’t think this difference should affect whether the example gets classed as one of wh-misidentification, and this is the result given by the account I’ve sketched above; that account of wh-misidentification requires that one have grounds that justify one in believing the existential and that one believes it on this basis, but it doesn’t require that the existential is true. On Morgan’s account, however, the grounds I have in the modified example clearly don’t offer me independent knowledge that something is a skunk, since this existential claim is false. So the account rules this judgment, made on these grounds, as immune to wh-misidentification. That seems like the wrong result. We might be tempted to think that this is a superficial problem, since we can just replace the requirement of independent knowledge in Morgan’s account of immunity to wh-misidentification with a requirement of independent justification. However, this won’t work. The criterion for knowledge to be independent is supposed to work because you can’t get knowledge from falsehood (Morgan 2019: 447); but almost everyone will agree that you can get justification from falsehood (as when Smith gets a justified belief that the person who will get the job has ten coins in his pocket by inferring this from the false lemma that Jones will get the job).

This point leads us to the primary problem with Morgan’s account. There have been a number of examples that suggest that the ‘fact about knowledge’ Morgan appeals to, that there’s no getting knowledge from a falsehood, is simply false. Take an example from Ted Warfield (2005). I might have miscounted the number of people at a talk I’m giving, reaching a total of 67 when they are actually 66 in the room. If I infer from this that the 100 handouts I’ve printed off will suffice, this seems to be knowledge even though my premise is false. My purpose here is not to join or try to resolve this debate about knowledge (though I do think that knowledge from falsehood is possible: see McGlynn 2014: 7). My point is just that there’s a major epistemological controversy at the heart of Morgan’s account.Footnote 28 These two worries with Morgan’s view should suffice to cast some doubt on the idea that we can simply avoid the issues raised by my account without incurring significant costs.Footnote 29

6 Concluding remarks

I have argued that wh-misidentification and its associated notion of immunity are genuine phenomena, at least in the sense that they are neither ‘spurious’ nor mere superficial variants of their de re analogues. I’ve also suggested that we can offer an account of wh-misidentification that both respects the differences between these varieties of misidentification and illuminates what they have in common. What we surely want to know now is what the significance of all this is, if it’s correct. Why does it matter if Pryor’s right that misidentification and immunity to misidentification come in more than one flavour, and what are the consequences of adopting the specific account I have offered?

I mentioned in the introduction that Pryor argues for the significance of immunity to wh-misidentification in part by contending that it allows us to settle a dispute between Shoemaker and Evans. The dispute concerns the bearing of the apparent metaphysical possibility of quasi-remembering—having memory impressions of an event ‘from the inside’ that may derive from an event either in one’s own past or in the past of someone else—for the thesis that memory-based judgments about one’s own past are immune to error through misidentification. Evans (1982) holds that such judgments are immune, since the grounds served up by memory are already first-personal, and so judgments about one’s own past based on such grounds will not be based on any identification, leaving no scope for error through misidentification. In contrast, Shoemaker (1970) points out that if I mistakenly judge that I was F, having quasi-remembered someone else’s past, this does seem to involve an error through misidentification; I have misidentified myself as the person whose past my memory-impressions derive from, and reached a false judgment about my past on that basis. Memory-based judgments about one’s own past may enjoy a kind of ‘de facto’ immunity to error through misidentification, according to Shoemaker, since quasi-remembering is merely possible, but that’s it. Pryor sides with Shoemaker in this debate, though he adds that Shoemaker’s claims are most plausible when taken as claims about immunity to wh-misidentification. Even if it must be conceded that such judgments are immune to de re misidentification, ‘with respect to the most interesting sort of immunity, Shoemaker is right: our first-person memory-based beliefs do not have that sort of immunity’ (1999: 272)—or rather, they have it ‘at best’ only in a de facto sense (1999: 290).Footnote 30

One key reason Pryor offers for thinking that Shoemaker’s claim is more plausible when interpreted as concerning immunity to wh-misidentification is that one of Evans’s main objections to Shoemaker lapses if we do. Evans’s objection, as Pryor interprets him, is that in cases in which one has quasi-remembered events from another person’s past, one won’t typically be in a position to hold de re thoughts about that person in virtue of this link, and so one won’t be able to so much as entertain the false identity claim that would need to be in play for there to be room for misidentification (Pryor 1999: 293; compare Evans 1982: 243–244). As one might expect, Pryor’s response is that even if we concede the point, it tells us nothing about whether memory-based judgments about one’s past are immune to wh-misidentification; this is the application, advertised in the introduction, of Pryor’s claim that a judgment can be immune to de re misidentification without being immune to wh-misidentification.

The on-going philosophical interest in competing accounts of wh-misidentification in large part concerns their bearing on Pryor’s intervention into this debate.Footnote 31 Myself and others have argued against Pryor’s claim that casting Shoemaker’s side in terms of immunity to wh-misidentification makes it more plausible (see McGlynn 2016 and Morgan 2019), and I’m still inclined to think that’s the right conclusion. But the matter deserves renewed attention in light of what I’ve argued here, and I haven’t as yet done anything to answer the second question posed above, concerning the impact on the debate of adopting my particular conception of wh-misidentification rather than one of its rivals. While I lack the space to answer that question here, I hope to have made sufficient progress on refining our understanding of wh-misidentification and how it relates to and differs from de re misidentification to set the scene for the necessary discussion.

Notes

I’ll stick to the shorter label, but I note that we might more informatively call this ignorance through misidentification.

As Wright notes (2012: 253), this really characterizes ‘basic’ cases of de re misidentification; there are slightly more complex cases, but they differ from the basic ones only in entirely superficial ways and so I ignore them here.

Pryor prefers to define immunity first for pairs of propositions and grounds (1999: 279, 283), rather than judgments and grounds, but nothing turns on this here. Notice that the characterisation just offered doesn’t require that one believe the mistaken identity claim, nor that one’s judgment that a is F is epistemically based on such a belief. A number of philosophers have suggested that a judgment can be vulnerable to de re misidentification even when made on grounds that are free of any identity claims through having an identification as a presupposition (Coliva 2006; Wright 2012), or in Pryor’s terminology, a judgment can rest on an identification without being based on it (1999: 291).

Unhelpfully, this is sometimes offered as a characterisation of immunity to error through misidentification in general, without any heed being paid to the distinction between de re misidentification and wh-misidentification (e.g. Wright 1998; Stanley 1999; Stanley 2011; Hamilton 2013; and Salje 2017).

One’s grounds G offer one knowledge that P just in case, were one to be believe that P on the basis of G and to possess no defeating evidence, then one would know that P (Pryor 1999: 281-2)—so that it being the case that one’s grounds offer one knowledge that P doesn’t entail that one knows that P, or that one believes that P, or that one’s grounds offer one all-things-considered justification for believing that P. However, this does introduce a factive notion into the characterisation, and this has some peculiar consequences which I have discussed elsewhere (McGlynn 2016: 34-5); I won’t rehearse that discussion again here, though I discuss this issue briefly in Sect. 5 below.

If this seems too far-fetched, we can change the example to involve another animal with a distinctive odour but without distinctive visual identifying marks.

I here make good on an earlier promise to unpack my worries with Smith’s argument (2016: 41 fn14). See García-Carpintero (2018: 3320 fn20) for a different worry with Smith’s argument.

Wright also discusses some other examples that he argues are problematic for Coliva (2012: 258-9); I leave those aside here.

Thanks to Michele Palmira here.

In fact, the ‘straw man’ proposal Coliva attributes to Wright in this passage isn’t the proposal he criticizes, which is ‘The person who caused these footprints in the sand has passed this way already’.

Thanks to anonymous referees who helped me better understand Coliva’s proposal here.

Wright isn’t explicit about this, but he does comment earlier in his paper on the possibility of altering Perry’s example so as to be a case of error through misidentification; see Wright (2012: 259).

This points to a mild disagreement with Garcia-Carpintero. He suggests that Coliva’s proposal works for the skunk example due to ‘idiosyncrasies of Pryor’s example’ and he offers an alternative example intended to show that Coliva’s proposal doesn’t work in cases where there the subject has no grounds for a unique existential (2018: 3320). I think that the differences between Garcia-Carpintero’s example and Pryor’s are purely cosmetic, and that it is commentators such as Coliva and Wright that have introduced the ‘idiosyncrasies’. One (admittedly minor) reason this matters is that Palmira has suggested on Coliva’s behalf that she might contend that Garcia-Carpintero’s case isn’t one of misidentification at all (2019: 162). I don’t find this reply all that plausible for Garcia-Carpintero’s case, but it seems tantamount to an admission of defeat to take this line with respect to the very example Pryor used to introduce the phenomenon of wh-misidentification.

It’s not enough to require, as an earlier formulation of this clause did, that one’s grounds do not ‘derive from’ facts about the object a. Suppose that I know that a particular smell is equally likely to indicate skunks in my garden or that my neighbour is burning tires, and I also know that the smell of burning tires will drive all animals out of my garden. I smell the distinctive smell, and this justifies me in judging that there’s either a skunk in my garden or that my neighbour is burning tires again. I then see what appears to be a skunk in my garden, but in fact it’s a realistic skunk decoy planted by my neighbour to disguise his tire-burning activities. My combined olfactory and visual grounds justify me in believing the existential that there’s a skunk in my garden, and that this particular object (the decoy) is a witness to this existential. Unlike in Pryor’s original example, however, my grounds in this variant do derive from the object I misidentify as a skunk, namely the decoy. Still, this seems to be a case of misidentification. On the formulation of clause iv’’. offered in the text, this is so because one’s grounds for the existential do not derive from the fact that this object is a skunk in my garden; indeed, there is no such fact, since the object in question is a mere decoy. I’m grateful to an anonymous reviewer for presenting this variant as a counterexample to my earlier formulation, and prompting me to think more carefully about how to state my clauses; Jonathan Jenkins Ichikawa and Stephan Torre raised similar points in discussion. Interestingly, the variant example appears to be a counterexample to Daniel Morgan’s rival account of wh-misidentification, discussed below.

An anonymous reviewer reasonably complains that one might find it unnatural to think of such cases as involving wh-misidentification, since one correctly identifies a witness to the existential, and they suggest adding a condition to the effect that a is not F (parallel to Pryor’s condition iii’ in Sect. 2 above). The point is related to one made by Wright, who observes that it seems infelicitous to describe cases of wh-misidentification in which one’s final judgment is false as cases of error through misidentification, since ‘the error consists in a misidentification, rather than being caused by one’ (2012: 256). Cases of de re misidentification which result in a true judgment are easier to stomach, since one’s final judgment still rests on a misidentification; the corresponding putative cases of wh-misidentification don’t even rest on a mistaken identity claim. I’m sympathetic to the idea that there’s an oddity to describing these as cases of misidentification, and I could perhaps be persuaded that an additional condition is required, but I’m currently inclined to think that what’s key to the phenomenon is the shared structure picked out by the clauses I’ve offered, rather than whether the usual label remains apt once we recognise that the range of cases that exhibit that structure is broader than we might have supposed prior to Pryor’s paper; see the main text below for further discussion. Of course, this issue about what’s most important here raises the question of what work we want the notion of wh-misidentification to do—I touch on this in the conclusion, but mostly have to leave the issue for another occasion.

Thanks to Alex Byrne for the example and for pushing me to modify my account to deal with it. I suspect that condition ii’’. needs finessing, but I won’t attempt that here, partly for methodological reasons I’ll come to shortly in the main text.

As with the characterization of de re misidentification offered in Sect. 2, this should be seen as characterizing basic cases of wh-misidentification; see, e.g. Hu (2017) for some refinements one might want to add to accommodate further cases. This way of characterising ‘immunity’ ignores the main proposal of McGlynn (2016), which is to rethink the modality implicit in the notion; this doesn’t reflect any change of mind on my part, but rather that I don’t want to introduce further complexities here.

Thanks to an anonymous reviewer for pushing me to be clearer on this.

Moreover, these differences mean that Pryor is unable to characterise immunity to wh-misidentification in a parallel way to how he understands immunity to de re misidentification, introducing further differences and complexity; see McGlynn (2016: 34–35) for discussion.

Pryor also makes this connection to the Gettier problem, though in the context of introducing the notion of a subject’s grounds offering them knowledge of a proposition (1999: 281).

I don’t intend this as a general account of why the subjects in Gettier cases are ignorant, since it faces familiar problems; for example, I don’t think it works for ‘fake barn’ cases (see McGlynn 2014: 8–10).

Gettier’s own examples all involve a subject deductively inferring a justified true belief from a justified but false belief, and the inference in the skunk example is ampliative. However, we already know to expect variety here. For example, Bertrand Russell’s stopped clock is often taken to show that Gettierised beliefs don’t need to be inferential at all; one truly and justifiably believes that it is two o’clock based on the position of the clock hands, without having inferred this from anything—but this belief is merely true by luck, since the clock’s hands uncharacteristically got stuck twelve hours prior.

One might wonder, given what I’ve written above, whether misidentification and vulnerability to error through misidentification are just the same notion. In my view, they are not. Consider another example of Wright’s, in which I see my Aunt Lillian at close quarters and judge that Aunt Lillian is wearing an extraordinary hat today (2012: 42). Wright insists that this judgment is not immune to error through misidentification, since (unlikely as this may be) my aunt may have an identical twin I don’t know about and couldn’t distinguish visually even at a short distance. I agree (2016), and it follows from this that the judgment is likewise vulnerable to misidentification more generally. But the judgment, made on these visual grounds, is not a case of misidentification if it really is my aunt and she has no twin; it’s not merely luck that my judgment is correct, given those grounds, in the Gettierish way I’ve suggested is characteristic of misidentification. So the example suggests that a judgment, made on certain grounds, can be vulnerable to error through misidentification and vulnerable to misidentification without thereby being an actual case of misidentification.

Thanks to Manuel Garica-Carpintero for pushing me to say something in response to Morgan’s account.

The claim will be familiar from ‘no false lemmas’ accounts of knowledge, according to which Smith’s justified true belief that the person who will get the job has ten coins in his pocket fails to be knowledge because it rests on the ‘false lemma’ that Jones has ten coins in his pocket.

As we noted with Pryor’s account above: see McGlynn (2016: 34–5).

As mentioned in footnote 15 above, there may be a third problem, since a variant of Pryor’s example appears to be a counterexample to Morgan’s account. I lack space to unpack the details of this worry here.

Hu (2017) argues that it also has significance for debates concerning whether examples of thought-insertion show that our beliefs about our own minds are vulnerable to misidentification.

References

Ball, B., & Blome-Tillmann, M. (2014). Counter closure and knowledge despite falsehood. The Philosophical Quarterly, 64, 552–568.

Buford, C., & Cloos, C. M. (2018). A dilemma for the knowledge despite falsehood strategy. Episteme, 15(2), 166–182.

Cappelen, H., & Dever, J. (2013). The inessential indexical: On the philosophical insignificance of perspective and the first person. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Coliva, A. (2006). Error through misidentification: Some varieties. Journal of Philosophy, 103, 403–425.

Coliva, A. (2018). Review of About oneself: De se thought and communication by Manuel García-Carpintero and Stephan Torre. Analysis, 78(4), 780–784.

Evans, G. (1982). The varieties of reference. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

García-Carpintero, M. (2018). De se thoughts and immunity to error through misidentification. Synthese, 195, 3311–3333.

Hamilton, A. (2013). The self in question. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Hu, I. (2017). The epistemology of immunity to error through misidentification. The Journal of Philosophy, 114, 113–132.

Jeshion, R. (2010). Singular thought: acquaintance, semantic instrumentalism, and cognitivism. In R. Jeshion (Ed.), New essays on singular thought. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Luzzi, F. (2014). What does knowledge-yielding deduction require of its premises? Episteme, 11(3), 261–275.

Luzzi, F. (2019). Knowledge from non-knowledge: Inference, testimony, and memory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

McGlynn, A. (2014). Knowledge first?. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

McGlynn, A. (2016). Immunity to error through misidentification and the epistemology of de se thought. In M. Garcia-Carpintero & S. Torre (Eds.), About oneself: De se thought and communication. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Merlo, G. (2017). Three questions about immunity to error through misidentification. Erkenntnis, 82, 603–623.

Morgan, D. (2019). Thinking about the body as subject. Canadian Journal of Philosophy, 49, 435–457.

O’Brien, L. (2007). Self-knowing agents. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Palmira, M. (2019). Arithmetic judgements, first-person judgements, and immunity to error through misidentification. Review of Philosophy and Psychology, 10(1), 155–172.

Perry, J. (1979). The essential indexical. Noûs, 13(1), 3–21.

Pryor, J. (1999). Immunity to error through misidentification. Philosophical Topics, 26, 271–304.

Recanati, F. (2007). Perspectival thought: A plea for (moderate) relativism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Salje, L. (2017). ‘Crossed wires about crossed wires: Somatosensation and immunity to error through misidentification.’ Dialectica, 71(1): 35–56.

Shoemaker, S. (1970). Persons and their pasts. American Philosophical Quarterly, 7, 269–285.

Smith, J. (2006). Which immunity to error? Philosophical Studies, 130, 273–283.

Stanley, J. (1999). Persons and their properties. Philosophical Quarterly, 48, 159–175.

Stanley, J. (2011). Know how. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Warfield, T. (2005). Knowledge from falsehood. Philosophical Perspectives, 19, 405–416.

Wright, C. (1998). Self-knowledge: The Wittgensteinian Legacy. In C. Wright, B. Smith, & C. MacDonald (Eds.), Knowing our own minds. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wright, C. (2012). Reflections on François Recanati’s ‘Immunity to error through misidentification: What it is and where it comes from’. In S. Prosser & F. Recanati (Eds.), Immunity to error through misidentification: New essays. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Acknowledgements

Thanks are due to audiences at the first Knowledge Beyond Natural Science workshop at the University of Stirling in May 2017, Workshop VI of the Diaphora project at École Normale Supérieure in Paris in June 2019, and the ‘Metaphysics and Epistemology of the Self’ conference put on by the What’s So Special About First-Person Thought? project at the University of Edinburgh in June 2019, and in particular to Alex Byrne, Annalisa Coliva, Giada Fratantonio, Manuel García-Carpintero, Marie Guillot, Jonathan Ichikawa Jenkins, Matt Jope, Giovanni Merlo, Daniel Morgan, Peter Pagin, Michele Palmira, Simon Prosser, Jim Pryor, François Recanati, Léa Salje, Lukas Schwengerer, Stephan Torre, and Crispin Wright. Finally, I offer special thanks to the two anonymous referees for this journal, who have offered numerous helpful and constructive comments that have greatly improved the paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

McGlynn, A. Immunity to wh-misidentification. Synthese 199, 2293–2313 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-020-02885-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-020-02885-9